Background: Li Wenliang, the Chinese physician who raised the first alarm about COVID-19, died of the disease on 7 February. Since then, the pandemic has taken the lives of at least 200 other doctors and nurses (1); lower-paid health care workers filling essential roles may be similarly imperiled.

In recent weeks, hospitals in some regions of the United States have been inundated with COVID-19 patients, thousands of nursing home residents have died of the disease, and many infected persons remain at home. Caregivers in these venues are at risk for exposure.

Objective: To assess the number of U.S. health care workers providing direct patient care who have risk factors for a poor outcome if they develop COVID-19 or who lack health insurance or sick leave.

Methods and Findings: We analyzed the most recently available data from 2 in-person surveys of nationally representative samples of the civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population: the 2018 National Health Interview Survey (n = 72 831) and the March 2019 Current Population Survey (CPS) (n = 180 101).

We generated national estimates (and 95% CIs) by using weights provided in the surveys; the surveyfreq procedure in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute); and (for the CPS) replicate weights and the balanced repeated replication method.

In the National Health Interview Survey, we identified health personnel reporting direct patient contact (Figure) and determined how many had risk factors for poor COVID-19 outcomes (2), lacked health insurance or paid sick leave, could not afford needed prescription medications in the past year, and were very or moderately worried about medical costs.

Figure.

Flow charts showing data sources and inclusion criteria for cohorts analyzed.

CPS = Current Population Survey; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

* “Do you currently volunteer or work in a hospital, medical clinic, doctor's office, dentist's office, nursing home, or some other health care facility? This includes emergency responders and public safety personnel, part-time and unpaid work in a health care facility, and professional nursing care provided in the home.”

† Industry of employment was determined on the basis of Census Industry Classification Codes for Detailed Industry (4 digit): hospitals, 8190; nursing homes, 8270; and home care, 8170.

‡ “Do you provide direct patient care as part of your routine work? By direct patient care we mean physical or hands-on contact with patients.”

§ Elevated risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes was defined according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (2), age greater than 64 years, or a chronic condition, as detailed in the Table footnotes.

|| Analyses were based on responses to the following questions: “Are you covered by any kind of health insurance or some other kind of health care plan?” “If you get sick or have an accident, how worried are you that you will be able to pay your medical bills? Are you very worried, somewhat worried, or not at all worried?” “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed any of the following, but didn't get it because you couldn't afford it? Prescription medicines.” “Do you have paid sick leave on this main job or business?”.

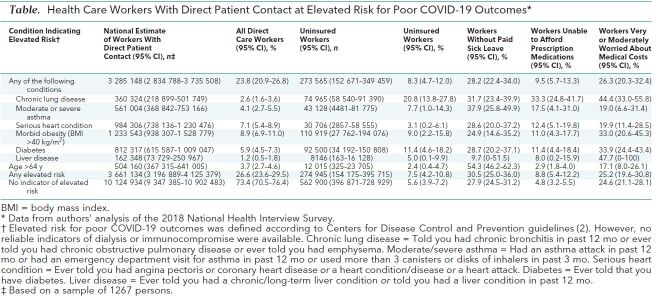

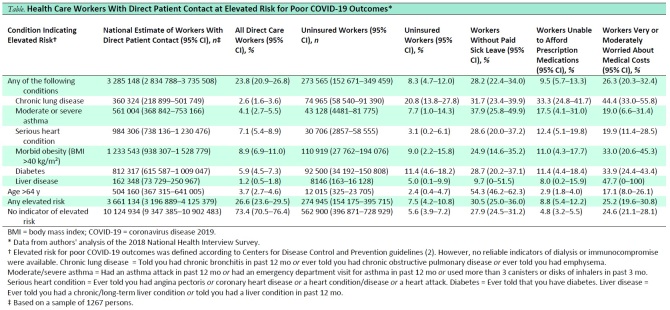

Of 13.79 million health care workers with patient contact, 3.66 million (95% CI, 3.20 million to 4.13 million), or 26.6% (CI, 23.6% to 29.5% ), were at risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes because of age or chronic conditions (Table). Of these high-risk persons, 275 000 (CI, 154 000 to 396 000), or 7.5% (CI, 4.2% to 10.8%), were uninsured, including 11.4% (CI, 4.6% to 18.2%) of those with diabetes and 20.8% (CI, 13.8% to 27.8%) of those with chronic lung disease other than asthma. In addition, 8.8% (CI, 5.4% to 12.2%) had been unable to afford medications and 25.2% (CI, 19.6% to 39.8%) worried about medical costs. Of all health care personnel with patient contact, 28.6% (CI, 25.6% to 31.5%)—including 1.12 million (CI, 0.90 million to 1.33 million), or 30.5% (CI, 35.0% to 36.0%), of those at risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes—lacked paid sick leave.

Table. Health Care Workers With Direct Patient Contact at Elevated Risk for Poor COVID-19 Outcomes*.

In the CPS, we identified workers in hospitals, nursing homes, and home care settings and determined their occupations, family incomes relative to the federal poverty level, and health coverage at the time of the survey (Figure).

Only 3.1% (CI, 2.8% to 3.4%), of hospital workers, or 233 000 persons (CI, 209 000 to 257 000 persons), were uninsured, but uninsurance rates among nursing home staff (11.5% [CI, 10.3% to 12.8%], or 193 000 persons [CI, 169 000 to 217 000 persons]) and home care workers (14.9% [CI, 13.7% to 16.1%], or 237 000 persons [CI, 216 000 to 258 000 persons]) exceeded the rate for the U.S. population as a whole (9.1% [CI, 9.0% to 9.2%]). Among nursing personnel in nursing homes and home care, 12.0% (CI, 8.4% to 15.6%) of licensed practical nurses were uninsured, as were 5.1% (CI, 3.6% to 6.5%) of registered nurses and 315 000 aides (CI, 285 000 to 345,000 aides)—more than one sixth of all aides in these settings.

Many health workers had family incomes below the poverty line, including 2.5% (CI, 2.2% to 2.8%) of hospital workers (188 000 persons [CI, 164 000 to 212 000 persons]), 11.7% (CI, 10.4% to 13.1%) of nursing home workers (196 000 persons [CI, 117 000 to 221 000 persons]), and 14.6% (CI, 13.2% to 16.0%) of home care workers (232 000 persons [CI, 207 000 to 257 000 persons]).

Discussion: Our analysis is limited by reliance on self-reported data from before the COVID-19 pandemic; some personnel with patient contact may now be furloughed or working from home. Data limitations prevented us from identifying personnel at risk due to immunosuppression or renal failure requiring dialysis. A lack of paid sick leave might not discourage physicians—about 6% of health care personnel—from heeding advice to self-isolate.

Despite these limitations, our data indicate that millions of health workers likely to be exposed to SARS–CoV-2 have medical conditions that increase their risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes. Many lack health insurance and paid sick leave, and more than 600 000 live in poverty, potentially compromising their ability to maintain social distancing outside their workplace (3). Poverty, particularly when coupled with lack of sick pay, might push minimally symptomatic workers to attend work.

Although Congress mandated free coronavirus testing for uninsured persons, the order has not extended health coverage to those requiring treatment. Likewise, the congressional mandate expanding sick leave benefits exempted entities with more than 499 employees, excluding 74% of hospital personnel and more than one third of nursing home and home care workers. Recently introduced bills address 2 of these shortcomings, offering hazard pay to essential workers (4) and universal, no-cost health coverage for the duration of the epidemic (5). In some locales, physicians and nurses are urging their institutions to increase the pay of lower-wage workers.

Millions of health personnel are assuming substantial risks to serve their communities. Depriving them of adequate income, sick leave, and insurance dishonors that service and threatens the well-being of both health workers and the public.

Biography

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-1874.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol and statistical code: Available from Dr. Himmelstein (e-mail, dhimmels@hunter.cuny.edu). Data set: Data used in the analyses may be downloaded for free from https://thedataweb.rm.census.gov/ftp/cps_ftp.html and www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2018_data_release.htm.

Corresponding Author: David U. Himmelstein, MD, 255 West 90th Street, New York, NY 10024; e-mail, dhimmels@hunter.cuny.edu.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 28 April 2020.

References

- 1. Kim S. More than 200 doctors and nurses have died combating coronavirus across the globe. Newsweek April 19, 2020. Accessed at www.newsweek.com/more-200-doctors-nurses-died-combating-coronavirus-1497181. on 11 April 2020.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information for healthcare professionals: COVID-19 and underlying conditions. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/underlying-conditions.html. on 9 April 2020.

- 3. DeLuca S, Papageorge N, Kalish E. The unequal cost of social distancing. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Accessed at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/from-our-experts/the-unequal-cost-of-social-distancing. on 11 April 2020.

- 4. Bolton A. Senate Democrats propose $25,000 hazard-pay plan for essential workers. The Hill 7 April 2020. Accessed at https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/491547-senate-democrats-propose-25000-hazard-pay-plan-for-essential-workers. on 12 April 2020.

- 5. Health Care Emergency Guarantee Act. Accessed at www.sanders.senate.gov/download/healthcare-covid-text?id=E0FDBE32-FF41-4367-A9CC-42EE4DFB233C&download=1&inline=file. on 12 April 2020.