Abstract

Purpose:

Myopia can cause many changes in the health of the eye. As it becomes more prevalent worldwide, more patients seek correction in the form of glasses, contact lenses and refractive surgery. In this study we explore the impact that high myopia has on central corneal nerve density by comparing sub basal nerve plexus density measured by confocal microscopy in a variety of refractive errors.

Methods:

Seventy healthy adult subjects between the ages of 21–50 years participated in this study. The study took place in two phases with no overlapping subjects (n = 30 phase 1 and n = 40 phase 2). In both phases an autorefraction, keratometry reading, corneal thickness measure and confocal corneal scan of the sub basal nerve plexus were performed for both eyes. There were 11 hyperopes (+0.50 to +3.50DS), six emmetropes (−0.25 to +0.50DS), 30 low myopes (−5.50 to −0.50DS), and 23 high myopes (−5.50DS and above). In the second phase of the study additional tests were performed including an axial length, additional corneal scans, and a questionnaire that asked about age of first refractive correction and contact lens wear. Corneal nerves were imaged over the central cornea with a Nidek CS4 confocal microscope (460 × 345 μm field). Nerves were evaluated using the NeuronJ program for density calculation. One eye was selected for inclusion based on image quality and higher refractive error (more myopic or hyperopic).

Results:

As myopia increased, nerve density decreased (t1 = 3.86, p < 0.001). We also note a decrease in data scatter above −7 D. The relationship between axial length values and nerve density was also significant and the slope was not as robust as refractive error (t1 = 2.4, p < 0.04). As expected there was a significant difference between the four groups in axial length (F3 = 19.9, p < 0.001) and age of first refractive correction of the myopic groups (14.9 vs 11.5 years; t46 = 2.99 p < 0.01). There was no difference in keratometry readings or corneal thickness between the groups (F3 = 0.6, p = 0.66 and F3 = 1.2, p = 0.33 respectively).

Conclusion:

Corneal nerve density in the sub-basal plexus decreased with increasing myopia. This could have implications for corneal surgery and contact lens wear in this patient population.

Keywords: confocal microscopy, cornea, myopia, nerve density, refractive error

Introduction

The corneal sub basal nerve plexus represents the densest innervation to the front surface of the eye, and is responsible for the keen sensation that the tissue experiences. Its structure can be easily examined in a clinical setting using confocal microscopy. To date, clinical studies have established normal ranges for many cell groups in different corneal layers, including endothelial counts and basal nerve density. This has been performed using many different brands of confocal microscopes.1,2 Here we expand on this knowledge by examining the nerve plexus differences in different groups of refractive errors.

It is well known that lasik refractive surgery in myopia alters the nerve plexus by reducing its density over a period of time.3 New information also suggests orthokeratology can cause changes to the density of the nerve bed.4 Some groups have documented that density decreases with age.5–8 To our knowledge, no research groups thus far have examined changes in nerve density specifically for patients of different refractive errors. Here we ask the question if there is a difference in corneal nerve density for high myopes, low myopes, emmetropes, and hyperopes.

Myopia is becoming more common around the world. In 2016, there were 1406 million identified myopes worldwide (22% of the population).9 Epidemiology varies widely by race and ethnicity.10 Of those identified myopes, 2.7% are high myopes (above −5 D).9 High myopia carries with it many other important co-morbidities and ocular health concerns such as retinal detachment, cataract, glaucoma, and retinal neovascularisation. It can also lead to changes in retinal and choroidal structure.10,11 It is reasonable to also consider changes to the front surface of the eye in higher myopes along with these co-morbidities.

The increased number of myopes also leads to an increased number of individuals who seek correction including refractive surgery to correct myopia. In the United States it was estimated that 596 000 people underwent lasik surgery in 2015 alone.12 Side effects of such a surgery observed frequently in clinical practice are drier eyes and changes in the sensitivity of the cornea. In addition, many myopes seek correction from contact lenses or orthokeratology, both of which can also alter the health of the front surface of the eye in many ways. The authors hypothesised from observations of a control group in a previous study that high myopes had lower nerve density than other refractive errors.13 Here we seek to quantify differences in nerve density in different refractive error groups in a group of healthy adults as they could have important implications on corneal health and refractive correction.

Methods

Subjects

Seventy subjects in total between the ages of 21–50 were recruited as part of this study and were selected specifically to have a wide range of refractive errors. They were part of the clinical population at the Midwestern University Eye Institute and were included if they were in the correct age range, had not had ocular surgery, and were free of corneal disease. There were 16 hyperopes between +0.50 D and +3.50 D, six emmetropes between −0.25 D to +0.50 D, 30 low myopes between −0.50 D and −5.50 D, and 23 high myopes at −5.50 D and above. All subjects underwent an autorefraction with keratometry measurement (non-cycloplegic; NIDEK http://www.nidek-intl.com/product/ophthaloptom/refraction/ref_auto/ark-1s.html), an anterior segment OCT to measure corneal thickness (Spectralis, Heidelberg, https://business-lounge.heidelbergengineering.com/us/products/spectralis/anterior-segment-module/), visual acuities to ensure 6/6 (0.0 log-MAR) or better acuity on a standard Snellen chart while corrected, and a scan of their central sub basal nerve plexus on a confocal microscope (NIDEK CS4, https://www.genop.co.za/media/pdf/Nidek/Nidek%20Files/Nidek%20CS4%20Confocal%20Scan.pdf). All measurements were initially gathered on both eyes and the included eye was selected during image processing. Eyes with more than 2 D of cylinder were excluded. The confocal scan was gathered with a 40× lens without a z-ring adaptor following the directions recommended by the manufacturer. A drop of 1% proparicaine was instilled in each eye before the scan began and a small amount of GenTeal gel (https://www.myalcon.com/products/otc/) was placed on the end of the objective. The gel touched the eye directly to conduct the scan, which was less than a minute for each eye. The patient was instructed to look straight ahead at a fixation target and the central point on the corneal was aligned and scanned. The software within the CS4 helped to align and continue fixation throughout the scan. It also provides outputs after the scan to insure these scans were of high quality. These scan metrics provided by the instruments were used in their intended clinical fashion. The z-location and reflected light intensity profile were evaluated to ensure high quality scans. Scans were also checked manually to make sure there was an image of the nerve plexus included for each subject. Thirty subjects were part of the phase 1 study group and 40 subjects that did not contain any duplicate subjects from the pilot participated in a second phase (total n = 70). Subjects from phase 1 were initially gathered to answer questions about the relationship between systemic health parameters and corneal microscopy measures (particularly endothelial cell density). In this study a large group of refractive errors was included and endothelial and nerve density measures were evaluated for these 30 patients in addition to other testing mentioned. The relationship between refractive error and nerve density was evaluated in this patient group first and found to be significant. Subjects in the second phase increased the sample size, completed additional tests to be completed to further learn about this relationship, and provided an opportunity to overcome limitations from phase 1 (particularly the lack of axial length measures and questions about the number of images needed). They were selected by refractive error. Subjects in phase 2 also participated in an A-scan measurement of axial length (IOL master, Zeiss https://www.zeiss.com/meditec/us/products/ophthalmology-optometry/cataract/diagnostics/optical-biometry/iolmaster-500.html), provided information on their first refractive correction and whether they wore contact lenses, and participated in additional confocal scans (three total on each eye). One subject was an outlier with a very high Rx (−24 D) and potential retinal changes, so that subject was not included in the data analysis. Data from both phases were combined together whenever possible. The procedures were explained and informed consent was gathered from all subjects in advance of participation. This study was approved by the Midwestern University IRB and followed the tenants of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Selection and processing of corneal scans

Scans from the CS4 confocal microscope result in 350 images of the cornea at different layers. The microscope is programed to scan every 5 microns until it reaches 350 images. It typically scans through the cornea more than once for most subjects, however this is dependent on the corneal thickness. From these 350 images, 1–4 are typically of the basal nerves. This can vary from no images of the nerves to eight or more images, depending on the scan quality. Based on the literature14 and previous work in our laboratory group, the image used for processing was selected using the following criterion: (1) had to be a full image, which was not cut off or darkened on either side (2) it appeared to have the most nerves present (3) it contained minimal keratocytes. Based on these criterion, the best image was selected from each scan for both eyes. In phase 2, the grader selecting the images was aware of the assigned patient group (hyperope, low myope, or high myope) but not the specific refractive error of the subject or the eye selected. In phase 1, there were no specific patient groups.

Previously, our group evaluated the effect of averaging three scans in comparison to using the best image available from anywhere in the three scans.15 We found the confocal scan technique to be repeatable (as long as the scan quality and z-location plot was good in all images) and a high cor-relation between the best scan and the average. Thus in this study, we selected the best image available for processing. All images were a 460 × 345 μm field.

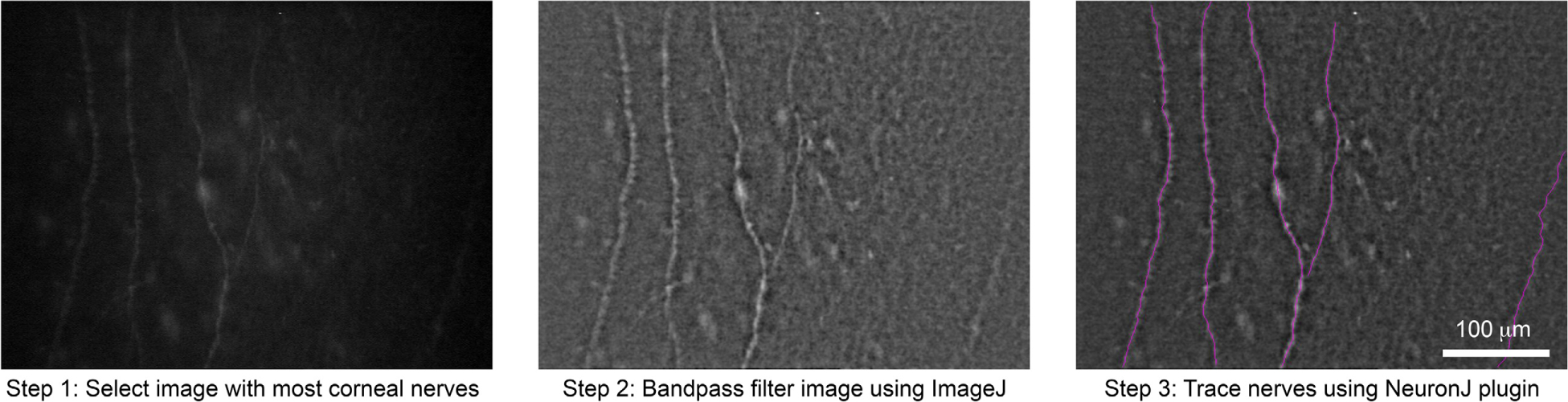

The images were then processed using ImageJ and the NeuronJ plugin for ImageJ (https://imagescience.org/meijering/software/neuronj/) which highlights and traces nerves. This is public domain software. The corneal nerves were traced using a semi-automated process. The trace was manually initiated and ended with clicks of the mouse button at the beginning and ends of individual nerves. The tracing algorithm computed the optimal path between these manually selected start and end points.16 We first enhanced the contrast of the nerves and then traced each visible nerve. This was an important step as many images still contained keratocytes. This allowed the length of each nerve and branch to be calculated. A sum of the nerves over the size of the field were used to calculate density. Figure 1 highlights the process of selecting and processing these images. After density was gathered for each eye, one eye was selected for inclusion in the analysis. This was the more myopic eye for all myopic patients and the more hyperopic eye for all hyperopic patients unless the image quality between the two eyes was not comparable. This was done to increase the prescription range of the data evaluated. If the eyes were the same refractive error with equal images, the right eye was selected. Comparison of groups was performed with an anova. Regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between factors.

Figure 1.

Image analysis process for one subject.

Results

Subject data

All four subject groups were similar in composition as shown in Table 1. Many emmetropes and hyperopes did not report an age of first refractive correction as they were still uncorrected at the time of the study, but there was difference between the low and high myopes for age of first refractive correction (14.9 vs 11.5 years; t46 = 2.99, p < 0.01). There was no difference in keratometry readings or corneal thickness between the groups (F3 = 0.6, p = 0.66 and F3 = 1.2, p = 0.33 respectively). Most of the myopes included in the study were soft contact lens wearers (90%). There was no difference in age between the four groups (F3 = 1.2, p = 0.33), and no relationship between nerve density and age (t1 = 0.56, p = 0.57).

Table 1.

Subject Information

| Hyperopes (plano to +3.50) | Emmetropes (−0.25 to +0.50) | Low myopes (−0.50 to −5.50) | High myopes (Over −5.50) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample size | 11 | 6 | 30 | 23 |

| Age | 29.9 (5.4) | 29.0 (5.5) | 27.0 (5.9) | 27.5 (5.5) |

| Average axial lengtha (mm) | 22.83 (0.96) n = 6 | 23.71 (0.80) n = 4 | 24.20 (0.63) n = 14 | 25.90 (1.0) n = 16 |

| Average flat k (D) | 43.0 (1.9) | 43.3 (1.8) | 43.7 (1.2) | 44.0 (1.9) |

| Average thickness (microns) | 531 (42) | 517 (51) | 540 (32) | 528 (27) |

| Densitya (microns·mm−2) | 10 476 (3678) | 7219 (2907) | 6817 (2902) | 5582 (2194) |

| Average Rxa (spherical equivalent) | 1.6 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | −2.6 (1.4) | −8.2(3.6) |

Values presented are mean and standard deviations. The axial length group has different sample sizes and these are noted within the table.

Denotes a significant difference between groups.

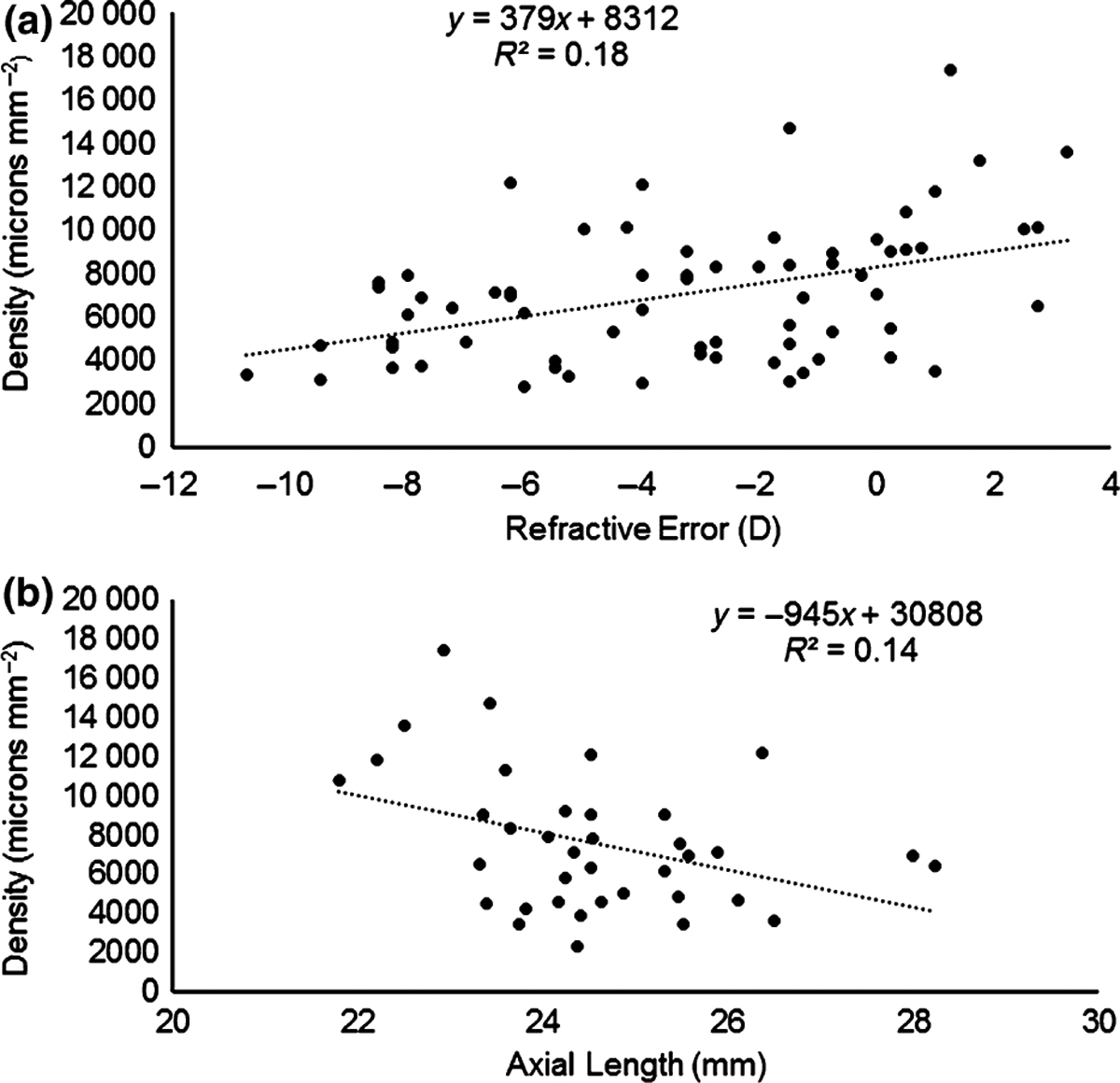

Comparison between refractive error and nerve density

Direct association between refractive error and nerve density was performed with linear regression analysis. Nerve density was normally distributed overall with a mean and median near 7000 (microns·mm−2) and a normal skew value of 0.87. With more myopic refractive error the nerve density decreased (t1 = 3.86, p < 0.001). (See Figure 2a). While low myopic powers have a great deal of scatter in nerve density from subject to subject, there is less scatter in the data for subjects over −7 D. Removing the subjects over −7 D decreases the R2 value of the regression from0.18 to 0.12.

Figure 2.

(a) The relationship between central sub-basal nerve density and refractive error. (b) The relationship between central sub-basal nerve density and axial length.

Comparison between nerve density and axial length

As expected there was a significant difference between the axial length for the hyperopes, emmetropes, low myopes, and high myopes (respective means 22.83, 23.70, 24.20, 25.90, F3 = 19.9, p < 0.001). The relationship between axial length and refractive error was very strong (t1 = 115.5, p < 0.001). In the subset of patients who performed an a-scan axial length in addition to nerve scans, the relationship between axial length and nerve density was calculated as shown in Figure 2b. It was significant (t1 = 2.4, p < 0.05), however the slope of this relationship was not as significant as the one illustrated in Figure 2a and more scatter was present, but it did have a smaller sample size.

Discussion

In vivo confocal microscopy is becoming a common clinical technique for careful evaluation of the corneal tissue at a cellular level. It is currently being used to evaluate healthy and disease states of the cornea at all levels.17,18 As more researchers and clinicians use this technology for patient care, standards for normal values for these cellular layers by age and other factors such as cell density are being established and used for comparisons in patient groups. This is important for the most accurate use of this technology.

In addition, researchers are also examining the normal anatomy of the cornea and corneal nerves of the sub basal nerve plexus with this technology. This aids in learning more about how our cornea functions.2,19–21 Comparisons of these data to clinical normal values on other instrumentation are also being performed. For example, a previous work found that confocal microscopy overestimates corneal thickness compared to OCT.22 Our data, on average, is in line with density measures by another research team using the CS4 instrument.3 This indicates that general concerns we have about data collection on this instrument such as the subject tiring are likely not impacting our results here in a meaningful way. Overall, this data adds to these efforts in a novel way by showing that as myopia increases nerve density decreases. We also note that above −7 D, the data does a better job of following this regression line than for data of lower myopes which is very scattered.

The mechanism and implications of this finding were not directly evaluated as part of this study, but we considered possibilities for what might lead higher myopes to have less central nerves than their low myope and hyperopic peers. It is possible that the mechanism is related to the longer myopic eye, that it may not allow nerves to travel all the way to the centre of the cornea where the scan is taken. However, a recent study4 found that there are fewer central corneal nerves after 1 month of ortho K in low myopes indicating the nerves may be pliable and able to be manipulated. We speculate that nerves may also be more fragile in higher myopia. This means that other factors such as likely long standing contact lens wear of the highly myopic group over time may have an effect which could be further explored.

This study does have several limitations we acknowledge in looking at the data. The first of which is that the first 30 subjects were gathered as part of different study evaluating corneal health. A second phase was added to include necessary testing such as the axial length measures. Therefore, not all the tests were performed on all the subjects as would be ideal. This also means that our different analysis have different sample sizes. Along with this there were several investigators taking and processing the data as part of this study in the different phases. We also acknowledge that the graders in phase 2 were aware of the subject groups as the image was chosen and density gathered by the group identifier is a weakness. They did not know the subject’s specific refractive error. We did evaluate the difference in data between group 1 and group 2 and found no differences as all graders used the same semi-automated program with the same selection criterion. Thus we do not feel there is bias from the grader knowledge in our data, but acknowledge the limitation none the less.

Furthermore, we did not gather information on the kind of contact lenses worn over time or the duration of contact lens wear for these patients. The question asked of the subjects was simply, ‘Do you wear contact lenses?’ This is the major limitation of the study which requires further follow up. We know that the higher myopes started wearing glasses significantly earlier, so they may also have begun to wear contact lenses earlier as well. They could also wear their contacts lenses for more hours a day which over a period of years may be able to cause the effect seen here. The difference in wear time could result in either nerve damage or optical scatter. This evidence is further supported by the fact that the relationship between refractive error and density was much stronger and more consistent than the relationship between axial length and density, indicating additional players other than axial length for this relationship. We are planning a follow up study to evaluate the length of contact lens wear and density in a systematic way in light of these results.

In addition to the possible implications in contact lens wear, the main implications for this study are in the consideration of refractive surgeries to the cornea. Clinically most patients who undergo lasik refractive surgery are low myopes which from these data indicates they could have a wide variety of nerve densities but will generally have less nerves than hyperopes. We do not fully understand why there is so much scatter in the density results of the lower myopes from this data and follow up studies evaluating the different characteristics of low myopes and how they relate to nerve density may be useful. However, high myopes also regularly undergo photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and other refractive surgeries which can also cause insult and injury to the basal nerve bed. Confocal microscopes are now a part of lasik care for evaluation of complications and general corneal health in some offices.23 It has been found in many studies that the nerves are injured in lasik surgery and begin to recover in a time period of 1–6 months,24,25 especially in the periphery. It has further been found that laser is superior to microkeratome for nerve regeneration.26,27 Long term follow up of the basal nerve plexus in PRK and lasik was found to be qualitatively the same.28 There is no indication if the baseline nerve density is important for the rate or success of nerve regeneration, but in light of this data it may be wise to measure nerve density on highly myopic patients before their surgeries to see what baseline is expected. It is not clear from this data if a reduction in corneal nerves plays any significant role in patient comfort or sensation. We did not evaluate sensation or any other functional measure of the corneal health as part of this study but in light of these results would consider function measures as part of a follow up to the data found here.

In conclusion, the results of this study find a novel reduction of corneal nerve density as myopia increases. We believe this novel finding may have important implications for corneal health that warrants follow up studies.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Office of Research and Sponsors Projects at Midwestern University internal grant to Wendy Harrison. The authors wish to thank Julie Welch, Donna Oller, Vicki Kimberlin, Dr. Michael Kozlowski and Dr. Balamurali Vasudevan for assistance on various stages of this project.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned in this article.

References

- 1.McLaren JW, Nau CB, Kitzmann AS & Bourne WM. Keratocyte density: comparison of two confocal microscopes. Eye Contact Lens 2005; 31: 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel DV & McGhee CNJ. Mapping the corneal sub-basal nerve plexus in keratoconus by in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 1348–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erie EA, McLaren JW, Kittleson KM, Patel SV, Erie JC & Bourne WM. Corneal subbasal nerve density: a comparison of two confocal microscopes. Eye Contact Lens 2008; 34: 322–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nombela-Paloma C, Felipe-Marquez G, Hernandez-Ver-dejo JL & Nieto-Bona A. Short term effects of overnight orthokeratology on corneal sub-basal nerve plexus morphology and corneal sensitivity. Eye Contact Lens 2016; 1–8. e-pub (doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000282). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erie JC, McLaren JW, Hodge DO & Bourne WM. The effect of age on the corneal subbasal nerve plexus. Cornea 2005; 24: 705–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederer RL, Perumal D, Sherwin T & McGhee CN. Age-related differences in the normal human cornea: a laser scanning in vivo confocal microscopy study. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 1165–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grupcheva CN, Wong T, Riley AF & McGhee CNJ. Assessing the sub-basal nerve plexus of the living healthy human cornea by in vivo confocal microscopy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2002; 30: 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieckmann G, Pupe C & Nascimento OJM. Corneal confocal microscopy in a healthy Brazilian sample. Arq Neurop-siquiatr 2016; 74: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016; 123: 1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster PJ & Jiang Y. Epidemiology of myopia. Eye (Lond) 2014; 28: 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verkicharla PK, Ohno-Matsui K & Saw SM. Current and predicted demographics of high myopia and an update of its associated pathological changes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2015; 35: 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Number of Lasik Surgeries in the United Staes from 1996 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/271478/number-of-lasik-surgeries-in-the-us/, accessed 17/August/16.

- 13.Reinard K, Yevseyenkov V & Harrison W. Corneal nerve health is related to HDL levels in patients with and without diabetes: a pilot study. American Academy of Optometry; 2015; conference number 155231. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarpa F, Grisan E & Ruggeri A. Automatic recognition of corneal nerve structures in images from confocal microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49: 4801–4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putnam N, Shukis C, Gabai C, Hundelt E, Vardanyan G & Harrison WW. Evaluation of corneal nerve images in an examination of corneal nerve density vs. refractive error. ARVO imaging in the eye seattle. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; conference number 2489514. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popko J, Fernandes A, Brites D & Lanier LM. Automated analysis of NeuronJ tracing data. Cytometry A 2009; 75: 371–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long Q, Zuo YG, Yang X, Gao TT, Liu J & Li Y. Clinical features and in vivo confocal microscopy assessment in 12 patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Int J Ophthalmol 2016; 9: 730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang H, Randon M, Michee S, Tahiri R, Labbe A & Bau-douin C. In vivo confocal microscopy evaluation of ocular and cutaneous alterations in patients with rosacea. Br J Ophthalmol 2016. E pub. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng T, Le Q, Hong J & Xu J. Comparison of human corneal cell density by age and corneal location: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. BMC Ophthalmol 2016; 16: 109. doi: 10.1186/s12886-016-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annunziata R, Kheirkhah A, Aggarwal S, Cavalcanti BM, Hamrah P & Trucco E. Two-dimensional plane for multi-scale quantification of corneal subbasal nerve tortuosity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57: 1132–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel DV & McGhee CN. Mapping of the normal human corneal sub-Basal nerve plexus by in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46: 4485–4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MeenakshiSundaram S, Sufi AR, Prajna NV & Keenan JD. Comparison of in vivo confocal microscopy, ultrasonic pachymetry, and Scheimpflug topography for measuring central corneal thickness. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 1057–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman SC & Kaufman HE. How has confocal microscopy helped us in refractive surgery? Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2006; 17: 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee BH, McLaren JW, Erie JC, Hodge DO & Bourne WM. Reinnervation in the cornea after LASIK. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43: 3660–3664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bragheeth MA & Dua HS. Corneal sensation after myopic and hyperopic LASIK: clinical and confocal microscopic study. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89: 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erie JC, McLaren JW, Hodge DO & Bourne WM. Recovery of corneal subbasal nerve density after PRK and LASIK. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 1059–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agca A, Cankaya KI, Yilmaz I et al. Fellow eye comparison of nerve fiber regeneration after SMILE and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK: a Confocal microscopy study. J Refract Surg 2015; 31: 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diakonis VF, Kankariya VP, Kounis G et al. Contralateral-eye study of surface refractive treatments: clinical and confocal microscopy evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014; 40: 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]