Abstract

Background:

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) smoke at disproportionately higher rates than those without SMI, have lifespans 25 – 32 years shorter, and thus bear an especially large burden of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. Several recent studies demonstrate that smokers with SMI can successfully quit smoking with adequate support. Further evidence shows that using technology to deliver sustained care interventions to hospitalized smokers can lead to smoking cessation up to 6 months after discharge. The current comparative effectiveness trial adapts a technology-assisted sustained care intervention designed for smokers admitted to a general hospital and tests whether this approach can produce higher cessation rates compared to usual care for smokers admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit.

Methods:

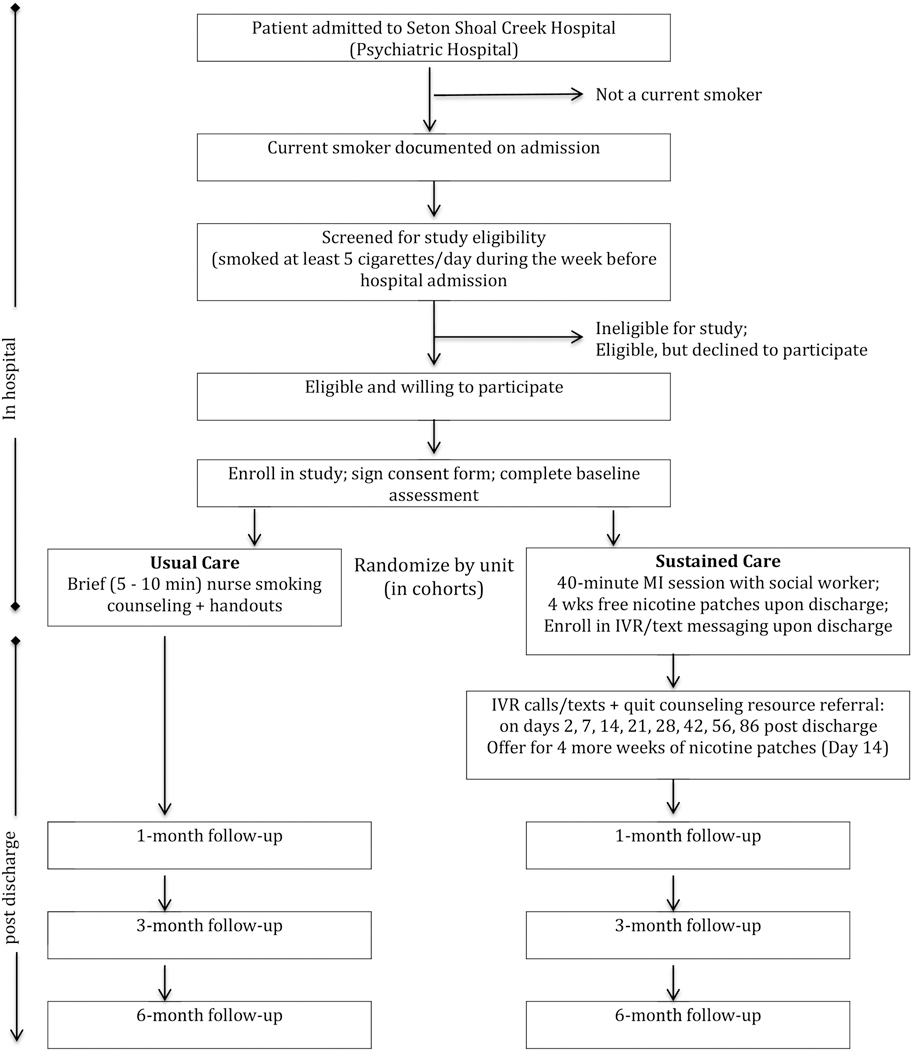

A total of 353 eligible patients hospitalized for psychiatric illness are randomized by cohort into one of two conditions, Sustained Care (SusC) or Usual Care (UC), and are followed for six months after discharge. Participants assigned to UC receive brief tobacco education delivered by a hospital nurse during or soon after admission. Those assigned to SusC receive a 40-minute, in-hospital motivational counseling intervention. Upon discharge, they also receive up to 8 weeks of free nicotine patches, automated interactive voice response (IVR) telephone and text messaging, and access to cessation counseling resources lasting 3 months post discharge. Smoking cessation outcomes are measured at 1-, 3- and 6-months post hospital discharge.

Conclusion:

Results from this comparative effectiveness trial will add to our understanding of acceptable and effective smoking cessation approaches for patients hospitalized with SMI.

Keywords: Hospitalized smokers, Smoking cessation, Psychiatric illness, Evidence-based interventions, Technology-based interventions, Comparative effectiveness trial

1. Introduction/background

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of death in the U.S., resulting in over 480,000 deaths each year[1]. In addition, smoking costs society more than $300 billion annually, with nearly $170 billion in direct medical costs and more than $156 billion in lost productivity[2]. Individuals with psychiatric disorders, approximately 20% of the U.S. adult population, smoke at disproportionately higher rates than the general population[3–6]. Those with serious mental illness (SMI) consume almost half (44.3%) of all cigarettes smoked in the U.S. [7] and have lifespans 25 – 32 years shorter than the general population [8, 9]. In this study, SMI refers to “individuals 18 or older, who currently or at any time during the past year have had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified in the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association and that has resulted in functional impairment, that substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” [10].

There is growing evidence that smoking cessation may improve psychiatric symptoms long-term [11], and many smokers with SMI want to quit smoking [12]. In 2011, 1.8 million U.S. adults received inpatient psychiatric treatment in the past year [13]. Today, the majority of psychiatric hospitals ban smoking on hospital grounds, thus creating an opportunity for inpatients to experience abstinence. Although smokers may be offered nicotine replacement therapy and other medications to ease withdrawal during hospitalization, they are rarely offered cessation resources at discharge, and most resume smoking after leaving the hospital [12].

The integration of evidence-based smoking cessation interventions within the current mental health treatment system is a public health priority [14]. Japuntich and colleagues describe a comparative effectiveness trial in hospitalized medical patients, titled Helping HAND (HH), comparing standard care to a sustained care smoking intervention that provided up to 3 months of free smoking cessation medication and 5 proactive, computerized telephone calls during which patients could elect to receive live telephone quit smoking counselling [15]. These post-discharge resources were specifically designed to reduce patient barriers to accessing evidence-based smoking cessation treatments. Rigotti and colleagues demonstrated clinical effectiveness of this sustained care model 6 months after hospital discharge, yielding significantly greater biochemically-verified point prevalence and continuous abstinence during the 6 months post discharge [16].

The overall objective of the current study is to adapt the HH sustained care model [16] for smokers with SMI receiving inpatient treatment in a psychiatric hospital, and to test the effects of this sustained care intervention (SusC) on smoking cessation. We hypothesize that: a) SusC compared to UC will result in significantly higher rates of cotinine-validated, 7-day point prevalence tobacco abstinence at 6-month follow-up and b) a higher proportion of SusC vs. UC patients will use evidence-based smoking cessation treatment in the month after discharge. Our secondary aim is to quantify total costs of SusC versus UC and incremental costs per quit. If effective and cost-effective, the adapted sustained care model could be delivered inexpensively and broadly disseminated.

2. Design

Helping HAND 3 (HH3) is a randomized, pragmatic effectiveness trial designed to assess benefit in real-world practice, testing the hypothesis that, among smokers in inpatient psychiatric treatment, an enhanced, SusC intervention program will result in superior long-term smoking cessation outcomes compared to UC (see Figure 1). Eligible participants are randomized by cohort into SusC or UC (see section 3.2 for more details), and are followed for 6 months after hospital discharge. The study enrollment period spans July 2015 through January 2019. Enrollment includes a total of 353 participants (SusC, n=174; UC, n=179) across 18 cohorts. Follow-up data will be collected through August 2019. This research is approved by the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board and is registered with the United States National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry (NCT02204956).

Figure 1. HH3 Study Flow.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting

This study is being conducted at a 94-bed urban psychiatric hospital in Austin, Texas that provides intensive psychiatric stabilization for adult patients, 18 years of age or older, who are dealing with emotional crises, depression and drug/alcohol dependence. The hospital houses a psychiatric intensive care unit, and facilitates a wide range of support groups that meet on a regular basis. Licensed staff are on call 24 hours per day to address the mental health needs of patients and their families. No smoking, tobacco or e-cigarette use is allowed in the hospital or on hospital grounds.

3.2. Participants

Patients are recruited from two hospital units that treat adult patients with SMI who have potential to meet study eligibility criteria. One unit (16 beds) primarily treats mood, anxiety and personality disorders and has a mix of patients with private and government-paid insurance; the other unit (24 beds) provides specialized treatment for thought disorders and more severe mood disorders, with patients mostly serviced through government-funded insurance. Excluded units include those providing intensive care to patients with acute psychiatric symptoms and those providing substance use detoxification protocols. Randomization is based on hospital unit; cohorts on each hospital unit are assigned at random to either SusC or UC in a yoked manner, such that a randomized cohort on each unit is followed by the opposite condition on that unit. This randomization design of cohorts by unit was selected to preclude possible contamination that might occur if patients within the same psychiatric unit were engaged in both conditions concurrently and were to share information with each other. The yoked design was implemented to ensure that each unit is balanced based on condition. A “wash-out” period of no recruitment occurs between cohorts until all participants from the previous cohort have been discharged to eliminate cross contamination between conditions. In total, there are 18 cohorts (9 in SusC and 9 in UC), with a final sample size of 353.

Inclusion Criteria - adult patients with SMI hospitalized on one of the two selected units who meet the following inclusion and exclusion criteria are eligible for study participation: Inclusion Criteria: (a) ≥18 years of age and (b) current smoker (i.e., smoking at least 5 cigarettes/day when not hospitalized). Exclusion Criteria: (a) current diagnosis of dementia or other cognitive impairment that would limit study participation, (b) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE: [17]) score < 24, (c) patient’s inability to provide consent for study participation due to his/her inability to demonstrate an understanding of study procedures as described in the statement of informed consent, after no more than two explanations, (d) current diagnosis of intellectual disability or autistic spectrum disorders, (e) current diagnosis of a (non-nicotine) substance use disorder requiring detoxification, (f) no access to a telephone or inability to communicate by telephone, (g) planned discharge to institutional care (e.g., nursing home, long-term rehabilitation, jail, etc., (h) no current or stable mailing address, (i) medical contraindication to the use of nicotine replacement therapy, and (j) currently pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant within 6 months. Structured diagnostic interviews are not used to further determine inclusion/exclusion criteria; the clinical psychiatric diagnoses recorded in the hospital medical record are used for this purpose. No specific level of motivation to quit smoking is required for study participation.

3.3. Study Recruitment

Smoking status of each patient is identified upon hospital admission and recorded in the medical record. Hospital-based study staff conduct two rounds of eligibility screening. First, they review medical charts daily to identify new admissions and assess inclusion/exclusion criteria. Within several hours of a patient being identified as potentially eligible, study staff consult with the physician or nurse for approval to approach the patient. Patients who appear to be smokers, based on their medical record, are further assessed in person for final eligibility and willingness to participate. To confirm smoking eligibility, patients are asked “During the past week, before you came into the hospital, how many cigarettes did you smoke in an average day? Patients who reported smoking 5 or more cigarettes/day were considered eligible, based on the smoking criteria. No other smoking requirements were assessed for eligibility.

3.4. Baseline Assessment Procedure

Once consent has been obtained, participants complete a baseline assessment (see Table 1). To minimize burden on hospitalized participants, data on patient diagnoses, discharge medications, and discharge disposition are recorded from hospital records; all other measures are obtained in a baseline assessment conducted by a research assistant after participant consent. In addition to baseline measures, detailed contact information for the patient and two “significant others” is collected in order to maximize connectivity during the post-discharge period and minimize loss to follow-up. These items include obtaining participants’ permission to leave detailed messages by phone, text and email.

Table 1.

Helping HAND 3 Study Outcome Measures by Assessment Time Point

| Measures | Screen | BSL | 1MFU | 3MFU | 6MFU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | |||||

| Medical Record Review for eligibility | X | ||||

| In-Person Screening | X | ||||

| MMSE - to assess cognitive capacity for | X | ||||

| Smoking History; FTND; Withdrawal | |||||

| Smoking History | X | ||||

| FTND - 6-item | X | ||||

| Motivation to Quit Smoking | X | ||||

| Thoughts about Abstinence (TAA; 4-item) | X | ||||

| Primary Outcome - Smoking Behavior | |||||

| Point Prevalence Abstinence (PPA) | X | X | X | X | |

| Smoking Cessation Treatment Use and | X | X | X | ||

| In-Hospital Smoking Intervention | X | ||||

| Sustained Care Helpfulness Questionnaire | X | ||||

| Bio-Verification | |||||

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | X | ||||

| Saliva Cotinine | X | ||||

| Psychiatric Symptoms | |||||

| PROMIS – Depression Short Form 8a | X | X | X | X | |

| PROMIS – Anxiety Short Form 8a | X | X | X | X | |

| BASIS 24 – Psychosis Subscale | X | X | X | X | |

| BASIS 24 – Emotional Lability Subscale | X | X | X | X | |

| Psychiatric and Medical History/Hospital | |||||

| Treatment History Interview | X | X | X | X | |

| Alcohol and Drug Involvement | |||||

| Alcohol/Drug Use Quantity and Frequency | X | X | X | X |

3.5. Assignment to Study Condition

3.5.1. Usual Care (UC)

Participants being treated on a unit assigned to the UC condition receive a brief 5- to 10-minute tobacco education session that all hospitalized smokers receive, delivered by a hospital nurse. The admitting nurse provides patients identified as smokers with brief smoking cessation information and advice during admission, along with an offer to use nicotine replacement therapy during their hospitalization. If the patient is too unstable at the time of admission, the nurse on duty provides this information, once the patient is stabilized. During this session, patients are advised to quit smoking and given written handouts describing the stages of readiness for quitting smoking, self-monitoring and self-management of smoking situations, and tips for quitting smoking, including relapse prevention, managing stress, and use of nicotine replacement therapy.

3.5.2. Sustained Care (SusC)

Those assigned to the SusC condition receive the same, nurse-delivered brief tobacco education session provided to UC participants, using the same guidelines. The additional inpatient smoking counseling session is modeled after the standardized protocol that Rigotti et al. [16] implemented for medical inpatients in the previous HH study, with specific modifications tailored for patients with SMI. More specifically, SusC participants receive a 40-minute, in-hospital counseling intervention from a trained social worker, based on motivational interviewing [18, 19]. This session is designed to facilitate decision-making about smoking cessation and foster receptivity to engage with post-discharge cessation resources offered in this condition; it is not intended as a stand-alone smoking intervention. Upon discharge, participants receive 4 weeks of free transdermal nicotine patches (TNP), followed by up to 8 automated interactive voice response (IVR) or text messages, during which they are offered free telephone cessation counseling. They also receive an offer for another 4 weeks of TNP, totaling 8 weeks of free TNP.

Hospital-based, Masters’ level social workers are trained to serve as smoking cessation counselors for this comparative effectiveness trial. Smoking counselors check in with the patient’s nurse or physician to confirm that the patient is stable enough, and to coordinate with other required treatments, before approaching the patient to deliver the intervention. Smoking counselors follow a written protocol to standardize and guide delivery of the SusC in-hospital intervention, which is not part of routine hospital care. This protocol outlines a flow of specific content to deliver, while allowing the counselors to use motivational interviewing strategies to elicit and explore patient motivation and desire for smoking cessation throughout the session. Assignment of smoking counselors to recruited participants is done on a rolling basis to minimize bias. When a smoking counselor is assigned as the patient’s hospital social worker, they will not provide the SusC smoking intervention, in order to keep these two roles separate and distinct. The Principal Investigator (R.A.B.) and Project Director (J.H.) provided the smoking counselors with initial training in tobacco cessation counseling and motivational interviewing in preparation for intervention delivery, and offered ongoing supervision, which included didactic discussion of core concepts, experiential role-playing with protocol-specific practice, and review of recorded interventions with counselor self-reflection and supervisor feedback. The intent is to record all sessions and use a random sampling for supervision.

3.5.2.1. Eight-Week Supply of Free Nicotine Patches

Upon hospital discharge, smokers assigned to SusC receive 4 weeks of TNP, based on the dose they received while in the hospital. The offer for more patches begins at the 3rd IVR contact (2-week post discharge call/text), to allow research staff time to express mail more patches, following a step-down protocol, to the patient without a gap in medication coverage. Participants are asked if they are still interested in quitting smoking, and if “yes,” would they like to receive 4 more weeks of nicotine patches. If the patient does not respond to the 2-week post discharge call/text, the offer for more patches is made again at the 3-week post discharge outreach. Only those participants who actively request additional patches through this system will receive another 4-week supply. Thus, SusC participants are eligible to receive up to 8 weeks of free TNP post hospital discharge.

3.5.2.2. IVR, Text Messaging and Proactive Telephone Counseling After Hospital Discharge

SusC is delivered via an automated interactive voice response (IVR) telephone system during the first 3 months after discharge. IVR makes proactive phone calls and sends text messages that can improve response rates by making multiple contacts outside of normal business hours. It offers pre-recorded messages and interactive questions, based on the participant’s responses. These messages and questions inquire about the participant’s smoking, intentions to quit, desire for additional nicotine patches, and interest in connecting with free telephone quitline counseling. The IVR and text message program component are provided by TelASK Technologies, Ottawa, Canada.

In keeping with the previous HH protocols, each IVR call/text message aims to achieve four goals: (1) assess smoking status, nicotine patch use, and side effects, (2) motivate and reinforce participant’s desire and efforts to quit smoking, (3) connect participants with telephone counseling, and (4) offer to send refills of nicotine patches.

Participants who indicate interest in counseling are transferred to the quitline and receive the standard telephone counseling package of up to 5 proactive calls over 3 months with unlimited inbound calls. Cessation counseling is provided by Optum (formerly Alere Wellbeing), the quitline provider for 27 U.S. states and more than 650 employers and health insurance providers. Optum’s counseling protocol aims to provide (1) cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation and relapse prevention tools, tailored to the individual smoker’s characteristics, and (2) medication adherence support, with the goal of completing a full course of medication for those using this resource. Optum provides specialized counselor training on how to address mental health issues [20] and has a protocol for addressing suicidal ideation if reported by callers.

4. Adaptations to the Original Helping HAND studies (HH1 and HH2)

Several modifications were made to the original HH study methods and protocols to maximize participation of smokers hospitalized for SMI.

4.1. Motivation to Quit:

Whereas the HH studies required that patients plan to sustain or initiate a smoking quit attempt after hospital discharge as part of their inclusion criteria (endorsing ‘I will stay quit’ or ‘I will try to quit’ during eligibility screening), the current HH3 study did not assess plans to quit as part of the inclusion criteria. This decision was made to maximize patient inclusion. Rather, we chose to expand the 5-minute tobacco counseling offered to inpatients in HH and provide a 40-minute session that includes motivational interviewing. Our enhanced counseling session aims to help patients achieve three main goals: (1) reflect on their experience of managing nicotine withdrawal while not smoking in the hospital; (2) build internal motivation to remain smoke-free after hospitalization; and (3) utilize evidence-based smoking cessation treatment resources (i.e., free nicotine patches and quit smoking counseling) that are provided after discharge to help patients remain smoke-free. The session begins with open-ended questions to assess the patient’s reasons for wanting to participate in the study, and their experience with not smoking while in the hospital. Counselors then explore patients’ broader values and goals for after leaving the hospital, and how their smoking fits in with these. After establishing patient motivation, the session includes information and graphics, displayed in an easy-to-read format, to dispel common myths and concerns that may arise among smokers with SMI.

More specifically, smoking counselors review empirical data indicating that quitting smoking often improves psychiatric symptoms long-term, and that smoking cessation treatment is associated with fewer psychiatric hospital readmissions[21]. To address concerns about using support for smoking cessation, (e.g., the nicotine patch and smoking counseling) the counselors share simple graphs showing the effectiveness of combining these approaches, in contrast to the common, but ineffective, tendency of trying to quit on one’s own [22, 23]. At the end of this session, the smoking counselor describes the procedure for providing participants with free nicotine patches upon discharge, the importance of engaging with IVR telephone and text messaging, and options for accessing cessation resources post discharge. After this explanation of sustained care services, the smoking counselor assesses the participant’s receptivity to engaging with these free resources, and offers the opportunity to directly enroll them to receive free, proactive cessation counseling, shortly after discharge. Consistent with motivational interviewing, the smoking counselor shares information in a non-judgmental, nonprescriptive manner, while asking the patient “how does this fit with your experience,” and “how do you feel about engaging with any of the cessation resources.”

4.2. IVR Protocol - Number of Contacts:

To build upon the success of the previous HH studies [16, 24], we adapted Rigotti’s automated IVR messaging protocol [25], tailoring it for smokers with SMI. First, we added 3 additional time-points (highlighted in bold) to the 5 time-points used in the earlier HH study[16] for a total of up to 8 time-points of outbound phone calls at fixed times after discharge (2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks). These additional time-points are intended to provide more concentrated support for smokers with SMI, who may have a harder time quitting smoking.

A new innovation to the IVR system in the current study is the inclusion of text messages, beyond the traditional phone calls, to offer a more flexible alternative for engaging participants and connecting them with cessation resources. During the baseline assessment, participants are asked about their ability and willingness to receive interactive text messages, in addition to the automated phone calls, and only those who give permission are sent texts.

4.3. IVR Protocol - Number of Outreach Attempts per Contact:

In the original HH study, 8 phone attempts were made at each time-point to try and reach study participants. Given that we added 3 more time-points for outbound calls and texts in the current protocol, we decided to reduce the number of phone attempts from 8 to 6 at each time-point. Participants who agree to both calls and texts are sent a combination of alternating IVR and text messages (one of each, with identical messaging through both platforms), on three consecutive days, until they respond, for a total of up to 6 contact attempts. When participants do not respond to any of these 6 contacts, the system waits until the next scheduled contact to start this procedure again. This approach affords maximum flexibility, such that participants can respond to the IVR message at one contact, and text message at another, thus increasing the likelihood that they will engage with this sustained care program in some way. Those who are not able or willing to receive text messages get 6 phone attempts. The decision to reduce phone attempts from 8 to 6 at each time-point was intended to reduce “phone call fatigue,” and increase the likelihood that participants would engage with this program over the 3-month sustained care period. The addition of text messaging also means that participants can respond to the text at any time, unlike the phone calls that must be responded to in real time.

4.4. Quitline Counseling Resources:

In addition to the free telephone counseling offered in the earlier HH studies, participants in the current study are also offered an opportunity to receive web- and text-based smoking cessation counseling. Although web- and text-based resources were not initially offered at the time this study began, we decided to include these expanded options as soon as they became available through the telephone quitline. Thus, these resources were introduced in November 2016, after 63 patients had already received SusC, and were made available to the remaining 111 patients randomized to this condition. Although typically these add-on resources are only available through the quitline once smokers are engaged with telephone counseling, we arranged for Optum to offer web- and text-based cessation counseling as “first line” resources, so that participants could choose the type of support they would most likely use, without requiring acceptance of telephone-based counseling. Early experience with trying to contact study participants for telephone follow-up assessments revealed that many participants do not answer their phones, yet some will respond to texts or email. Thus, participants have the option to choose any or all of these resources, whether or not they choose to engage in telephone counseling, thereby creating more flexibility for patients to engage with cessation resources.

5. Treatment Fidelity

The smoking counselors follow a written protocol for the SusC in-hospital session to ensure consistent delivery of the content and motivational interviewing style over the course of the study. All in-hospital sessions are audiotaped, with permission from study participants, and a random subset of 15% are rated by independent raters to assess protocol adherence, with a checklist system used in prior trials [26]. One limitation of this study is that we are not using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity scale to evaluate motivational interviewing fidelity, as this was not a primary aim of the study. To provide more study-specific feedback to the smoking counselors, we provide an in-depth qualitative review, both written and through verbal discussion, of how well the counselor incorporated specific motivational interviewing skills and strategies within each section of the protocol, noting specific client and counselor statements, as examples. Through this process, we helped counselors reflect upon their biases, beliefs, and practice to enhance their ability to integrate a motivational approach into this counseling session.

6. Evaluation

6.1. Outcome Assessments and Retention Strategies

Study staff contact participants by telephone at 1-, 3- and 6-months after discharge to collect outcome measures, including smoking status, use of smoking cessation medications and quit coach counseling, mood/psychiatric symptoms, and hospital readmissions. The SusC group also answers questions about their experience and satisfaction with the post-discharge automated outreach communication and cessation counseling resources. To facilitate completing follow-up assessments, participants are asked to provide multiple forms of contact during the baseline assessment, including cell/home phone numbers and email address, and are asked for permission to leave detailed phone/text messages and emails. Furthermore, phone numbers and addresses are collected for two “significant others” (SOs); e.g., family, friends and/or co-workers (who don’t live with the participant), so that study staff can contact them to locate “lost” participants and to validate smoking abstinence, if needed. Participants are asked to sign a standardized letter, addressed to each SO, stating that the participant gives the SO permission and encourages them to share updated contact information and answer questions about smoking if the researchers contact them. When participants come due for their follow-up assessments, study staff make at least 10 phone attempts, calling at different times of day and days of the week, as needed to reach them. Text messages and emails are also sent (to those who give permission to be contacted this way) to schedule the assessment. When participants do not respond after multiple attempts, study staff contact the SOs to find alternative phone numbers and methods of reaching the participant. As a last resort, an abbreviated written survey that focuses on smoking status and use of other tobacco products is mailed to the participant’s home, along with a stamped return envelope, to assess primary outcomes.

Participants are compensated with a reusable MasterCard (ClinCard) onto which researchers can upload payments via a web portal after completing follow-up assessments. Compensation amounts are: $5 for completing the baseline assessment, $30 at the 1- and 3-month follow-ups, and $60 at the 6-month follow-up. Those who self-report 7-day point prevalence abstinence at the 6-month follow-up are invited to come back to the hospital for a brief bio-verification visit, during which saliva is collected for cotinine analysis and a breath carbon monoxide (CO) reading is obtained. Eligible participants who are asked to provide bio-verification are compensated with an additional $40.

6.2. Validation of Tobacco Abstinence

Biochemical confirmation is used to validate self-reported tobacco abstinence at 6-month follow-ups. This validation is completed during an in-person return visit to the hospital and includes both saliva collection for cotinine analysis with a 15 ng/ml cutoff [27] and carbon monoxide testing (≤8 ppm). Because NRT use produces a false positive cotinine, expired carbon monoxide (CO) will be substituted for cotinine in those reporting NRT use during the past 7 days. While a lower cutoff for carbon monoxide (≤4 ppm) has been suggested to confirm smoking abstinence [28], we elected to use the more traditional cutoff of ≤8 ppm, given that many of our study participants are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and are more likely to live in housing and communities with higher levels of ambient carbon monoxide [27]. In cases where a return visit to the hospital is not possible, study staff offer to meet participants at a convenient location or send a saliva collection kit. In addition, study staff call the participant’s significant other (SO) for a proxy report of the participant’s smoking status immediately after the self-reported abstinence. This report serves as verification for those instances where we are unable to obtain biochemical confirmation. This proxy report includes a brief, structured interview that asks the SO if the participant was smoking in the 7 days prior to his/her 6-month follow-up assessment, what type of contact the SO had with the participant during that time, and how confident the SO is regarding the participant’s smoking status. Study staff collecting this information are also asked to rate his/her perception of how reliable this SO proxy report appears to be. This is done routinely for all participants reporting 7-day abstinence at the 6-month follow-up, to ensure we collect some form of timely verification of participants’ non-smoking status.

6.3. Study Measures

See Table 1 for study measures and timepoints at which they are assessed.

6.3.1. Baseline Assessment

The baseline assessment consists of a brief smoking history, including years smoked, smoking rate, nicotine dependence (6-item Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, FTND [29]), past quit attempts, and use of smoking cessation treatments. Participants also complete the 4-item Thoughts About Abstinence Scale [30], adapted from Marlatt [31], that assesses commitment, desire, and expected success/difficulty with abstinence.

6.3.2. Primary Outcome – Smoking Behavior

Self-reported nonsmoking for the past seven days (7-day point prevalence abstinence, PPA) is the primary outcome, which is verified at 6-months by saliva cotinine analysis (≤15 ng/ml cutoff) [27]. We also assess sustained tobacco abstinence and duration of continuous tobacco abstinence after hospital discharge (i.e., time to first lapse). Since use of nicotine products produces a false positive cotinine, expired (CO ≤8 ppm cutoff) will be substituted for cotinine for those who report non-smoking during the past 7 days while using nicotine replacement therapy. Participants will be counted as smokers [27, 32, 33] if they self-report smoking, have a cotinine or CO measure that exceeds the cut-offs, or are lost to follow-up. Although self-reported nonsmokers who do not provide a saliva or breath sample may be counted as smokers, we do not want to rule out the possibility that their inability to provide saliva or breath samples is due to reasons other than misrepresentation of smoking. For this reason, we also employ validation of nonsmoking status by asking a significant other (“proxy validation”) as an alternative confirmation strategy. Some trials in hospitalized smokers have used this as a back-up strategy when a biochemical sample was not obtained [34–38]. As the gold standard, we will calculate self-reported point prevalence abstinence verified by either saliva cotinine or expired CO (only for those using nicotine replacement therapy) in reporting smoking abstinence. We will also report on proxy validation among those for whom we are unable to obtain saliva cotinine or CO, as another potential indicator of smoking abstinence.

6.3.3. Smoking Cessation Treatment Use and Adherence

At each follow-up, participants report on their use of smoking counseling and/or pharmacotherapy. Smoking cessation counseling is defined as telephone, in-person, web- or text-based counseling (individual or group) from any source including a physician; pharmacotherapy includes use of nicotine replacement therapy (nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler, or nasal spray), bupropion, or varenicline. Outcome measures include pharmacotherapy (any use, duration of use, and dose) and counseling (any use, number of contacts, contact for >1 month). Furthermore, participants are asked about use of electronic cigarettes and their main reason for using them (e.g., as an aid for quitting vs. as a substitute for cigarettes). At 1-month follow-up, participants in the SusC are asked about the helpfulness of the inpatient smoking counseling session, including the written materials provided by the smoking counselor. At 3-month follow-up, participants in the SusC are asked about the helpfulness of the sustained care intervention received after hospital discharge (i.e., IVR/text messages and cessation counseling via telephone, web and text).

6.3.4. Psychiatric Symptoms

Depressive symptoms are assessed using the 8-item short form (Depression 8a Participant Version) of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; [39, 40]). Anxiety symptoms are also assessed using the 8-item short form (Anxiety 8a Participant Version) of the PROMIS [39, 40]. PROMIS measures are the result of an NIH collaborative project and possess high reliability and validity [39, 40]. Psychotic symptoms are assessed using the 4-item Psychotic subscale of the Behavior and Symptoms Identification Scale–24 (BASIS–24; [41]). Emotional lability is assessed using the 3-item BASIS-24 subscale [41].

6.3.5. Alcohol and Drug Involvement

Alcohol and drug use quantity and frequency is assessed via a series of questions that have been used in prior tobacco research [42].

6.3.6. Health and Health Care Utilization Outcomes

6.3.6.1. Hospital Admissions (Psychiatric and Medical)

Primary and secondary discharge diagnoses, length of stay, type of insurance, discharge medications, and readmissions to the hospital will be abstracted from the patient’s medical record. Participants will provide information about non-smoking related treatments, e.g., medical and psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations and emergency room visits (including overnight stays at rehabilitation facilities). Smoking cessation medication usage will be tracked at each follow-up interview in both study arms.

6.3.6.2. Cost-Effectiveness

A secondary analysis will examine incremental cost effectiveness of SusC relative to UC. Exploratory analyses will examine the impact of SusC, relative to UC, on health and healthcare utilization, including psychiatric symptoms, hospital readmissions, and emergency room visits for both psychiatric and medical reasons. Cost per quit at 6-month follow-up will be evaluated following an algorithm similar to that used in the cost effectiveness analyses in the previous HH study [16], which is comparable to other published reports [43, 44]. These analyses will take a societal perspective, measuring direct and indirect costs incurred by relevant stakeholders: patients, providers (hospitals, tobacco quitlines), and payers (insurers).

7. Discussion

This comparative effectiveness trial aims to offer important insights for smokers with psychiatric illness. More specifically, this study aims to demonstrate that: a) SusC compared to UC will result in significantly higher rates of cotinine-validated, 7-day point prevalence tobacco abstinence at 6-month follow-up and b) a higher proportion of SusC vs. UC patients will use evidence-based smoking cessation treatment in the month after discharge. Our secondary aim is to quantify total costs of SusC versus UC and incremental costs per quit. Modelled after the sustained care intervention by Rigotti and colleagues, this study enhances their hospital-based intervention by adding a more substantive in-patient counselling session, based on motivational interviewing, and expands the automated, sustained care services offered after discharge to replicate their favourable outcomes with a harder-to-reach population [16]. Rigotti and colleagues demonstrated clinical effectiveness 6 months after hospital discharge, yielding significantly greater biochemically-verified, point prevalence abstinence relative to standard care (26% vs. 15%, relative risk [RR], 1.71 [95% CI, 1.14–2.56], p = .009) [16]. Sustained care also resulted in higher self-reported continuous abstinence rates during the 6 months post discharge (27% vs. 16% for standard care; RR, 1.70 [95% CI, 1.15–2.51]; p = .007). These findings are consistent with a 2008 meta-analysis indicating that post-discharge supportive counseling lasting at least one month is necessary to achieve long-term tobacco abstinence [45], highlighting the value and efficacy of offering extended smoking cessation resources after hospital discharge.

Addressing smoking cessation among people with SMI is critical, in that they have significantly shorter lifespans compared with the general population, often attributed to physical and not mental illness [46]. Numerous factors contribute to these health disparities, including lifestyle behaviors, treatment side effects, inequitable health care access, and other social determinants of health [47]. Historically, the treatment for psychiatric and physical illness has been compartmentalized, addressed separately by different medical care providers, leading to wider gaps in both care delivery and outcomes. In addition, some providers remain skeptical that people with SMI have the desire and ability to successfully quit smoking, further limiting their opportunities for cessation treatment. However, there is growing evidence to challenge these beliefs. Thus, healthcare systems treating psychiatric illness have a unique opportunity to bridge these gaps, by attending to critical health indicators that can have a significant impact on both physical and mental well-being.

Several recent studies provide evidence that smokers with psychiatric illness can successfully quit smoking with proper support. A randomized controlled trial across four public psychiatric inpatient hospitals in Australia compared usual care with an intervention comprising a brief motivational interview plus self-help materials, followed by 4-months of continued pharmacologic and telephone counseling support after discharge. Seven-day point prevalence abstinence was significantly higher for intervention participants (15.8%) than controls (9.3%) at 6 months post-discharge, but not at 12 months (13.4% vs. 10.0% respectively). Furthermore, participants in the intervention group, relative to controls, were significantly more likely to smoke fewer cigarettes per day, to reduce daily cigarettes by ≥50%, and to have made one or more quit attempts at both 6- and 12-months post-discharge [48]. Similarly, Prochaska and colleagues randomized patients in an acute hospital psychiatric unit (n = 224), regardless of intention to quit, into a tailored, computer-based intervention, using the transtheoretical model or usual care. [21] The intervention included a printed report, stage-matched treatment manual, individual inpatient cessation counseling, and an offer of 10 weeks of nicotine replacement therapy post-hospitalization. Verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence was significantly higher in the intervention group compared with usual care at months 3 (13.9% vs. 3.2%), 6 (14.4% vs. 6.5%), 12 (19.4% vs. 10.9%), and 18 (20.0% vs. 7.7%), respectively. Hickman and colleagues aimed to replicate the Prochaska trial with a racially and ethnically diverse sample of uninsured smokers with serious mental illness at a large, urban, public hospital [49]. Participants (n=100) were largely unemployed (79%), had unstable housing (48%), and reported illicit drug use in the past month (77%). Seven-day point prevalence abstinence for intervention versus control was 12.5% for intervention versus 7.3% for control at 3 months, 17.5% versus 8.5% at 6 months, and 26.2% versus 16.7% at 12 months, respectively. Together, these studies demonstrate strong support for providing smoking treatment during hospitalization along with ongoing resources post discharge to improve cessation among smokers hospitalized for psychiatric illness.

Although there have been concerns within the psychiatric healthcare community that quitting smoking might exacerbate mental health conditions, there is growing evidence showing that quitting smoking leads to significant long-term mental health benefits for people with SMI [11]. A systematic review of the changes in mental health after smoking cessation shows that quitting smoking was associated with significant improvements in anxiety, depression, stress, positive affect, and quality of life [11]. Moreover, a significant proportion of those with SMI want to quit smoking [12]. In a study of 100 adult smokers receiving inpatient psychiatric care, Prochaska found that 65% were in contemplation or preparation regarding their stage of change for smoking cessation and 74% stated a goal of wanting to reduce their smoking or quit for good [12]. Among smokers with SMI who expressed an interest in cutting down or quitting, 97% had made a past quit attempt, with the most recent quitting episode lasting a mean of 23 days [50]. While only 9% believed that they had an extremely or very high chance of being successful, 35% reported being extremely or very determined to quit [50].

Despite these findings, treatment for smoking cessation has not yet been fully adopted nor integrated into psychiatric care, and support for nonsmoking tends only to be addressed within the context of hospitalization, where patients are not allowed to smoke. To date, treatment follow-up and referrals to smoking cessation services are rarely provided. Therefore, identifying accessible and effective methods for providing ongoing support to smokers with SMI, starting in the hospital and extending post-discharge, appears to be an important step in helping to reduce the disproportionately high smoking rates in this population. While nicotine replacement therapy is widely available now to many hospitalized smokers, including those with SMI, this approach alone does little to foster cessation post-hospitalization. Significant numbers of people with SMI want to quit smoking, yet do not have high expectations for success [50]. For these individuals, hospitalization provides a unique opportunity for them to explicitly learn more about the quitting process, given that patients often go several days without smoking while in these smoke-free environments. Utilizing hospitalization as a “window of opportunity” to address patient smoking creates numerous possibilities for implementing innovative, personalized strategies that can identify and build upon patients’ internal motivation for change, while also addressing the unique barriers and challenges they face when outside of these restricted environments. Delivering a client-centered motivational counseling session to hospitalized smokers may begin to fill this gap. Such interventions can help patients reflect on their smoke-free hospital experience, identify their values and what is most important in their lives, and consider how remaining smoke-free could help them achieve their broader life goals[18, 19]. In addition, the use of automated, proactive resources, such as IVR, text messaging and other technology-assisted interventions, have been shown effective in a general medical population of smokers [16], and may help support quitting smoking among people with SMI, who often have limited access to quality care services once they leave the hospital. Offering an array of options for smokers to engage with quitting resources, including telephone counseling, web-based, and texting programs, may help smokers find an acceptable way to access quitting support, thereby increasing utilization and ultimate cessation. Beyond this, further research is needed to better understand the ongoing needs for support that smokers with SMI have to help them remain smoke-free as they transition from the hospital to their home environment, and for longer term cessation maintenance.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by grant # R01MH104562 to Drs. Richard A. Brown and Nancy A. Rigotti from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIHM). Susan Azrin, Program Officer at NIMH, provided input into study design decisions. NIMH had no role in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration

Dr. Richard A. Brown has equity ownership in Health Behavior Solutions, Inc., which is developing products for tobacco cessation that are not related to this study. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of Texas at Austin in accordance with its policy on objectivity in research.

Dr. Erika L. Bloom has been a consultant for WayBetter, Inc., the focus of which was related to tobacco cessation but not to this study.

Dr. Kelly Carpenter is an employee of Optum, the provider of the quitline program utilized in this study. Dr. Nancy Rigotti is a consultant for Achieve Life Sciences for an investigational smoking cessation aid that is not related to this study, and has been an unpaid consultant for Pfizer, which markets varenicline, also not used in this study. She also receives royalties from UpToDate for reviews of smoking cessation treatments.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES CITED

- 1.USDHHS, The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, C.f.D.C.a.P. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Editor; 2014. [accessed 2015 Apr 7]: Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, et al. , Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: An update. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2015. 48(3): p. 326–333. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JR, Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 1993. 54(3): p. 109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lising-Enriquez K and George TP, Treatment of comorbid tobacco use in people with serious mental illness. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 2009. 34(3): p. E1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. , Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2004. 61(11): p. 1107–15. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC, Vital Signs: Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years with Mental Illness — United States, 2009–2011 in MMWR. 2013. p. 81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al. , Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2000. 284(20): p. 2606–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. , Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. 13th Technical Report. 2006, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council: Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. , Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2005. 66(2): p. 183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, The Way Forward: Federal Action for a System that Works for All People LIving With SMI and SED and Their Families and Caregivers, Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee, Editor; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. , Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2014. 348: p. g1151. 10.1136/bmj.g1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JJ, Fletcher L, Hall SE, et al. , Return to smoking following a smoke-free psychiatric hospitalization. American Journal on Addictions, 2006. 15(1): p. 15–22. 10.1080/10550490500419011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. NSDUH Series H-45, HHS Publiation No. (SMA) 124–725. 2012, Rockville, MD: Substance Aubse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. , Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res, 2008. 10(12): p. 1691–715. 10.1080/14622200802443569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japuntich SJ, Regan S, Viana J, et al. , Comparative effectiveness of post-discharge interventions for hospitalized smokers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 2012. 13: p. 124 10.1186/1745-6215-13-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. , Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 2014. 312(7): p. 719–28. 10.1001/jama.2014.9237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Robins LN, and Helzer JE, The Mini-Mental State Examination. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1983. 40(7): p. 812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR and Rollnick S, Motivational interviewing: Helping people change, 3rd Edition 2013, New York: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollnick S, Miller WR, and Butler CC Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. 2008, New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.North American Quitline Consortium. Results from the 2012 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines. 2013; Available from: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.naquitline.org/resource/resmgr/2012_annual_survey/oct23naqc_2012_final_report_.pdf.

- 21.Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, et al. , Efficacy of initiating tobacco dependence treatment in inpatient psychiatry: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 2014. 104(8): p. 1557–1565. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. , Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. 2008, Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes JR, Keely JP, and Naud S, Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction, 2004. 99: p. 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigotti NA, Tindle HA, Regan S, et al. , A Post-Discharge Smoking-Cessation Intervention for Hospital Patients: Helping Hand 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Prev Med, 2016. 51(4): p. 597–608. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rigotti NA, Chang Y, Rosenfeld LC, et al. , Interactive Voice Response Calls to Promote Smoking Cessation after Hospital Discharge: Pooled Analysis of Two Randomized Clinical Trials. J Gen Intern Med, 2017. 32(9): p. 1005–1013. 10.1007/s11606–017-4085-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RA, Abrantes AM, Strong DR, et al. , Efficacy of Sequential Use of Fluoxetine for Smoking Cessation in Elevated Depressive Symptom Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2013. 10.1093/ntr/ntt134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2002. 4(2): p. 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, and Jao NC, Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res, 2013. 15(5): p. 978–82. 10.1093/ntr/nts205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. , The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 1991. 86: p. 11191127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall SM, Havassy BE, and Wasserman DA, Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1990. 58(2): p. 175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marlatt GA, Curry S, and Gordon JR, A longitudinal analysis of unaided smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1988. 56(5): p. 715–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, et al. , Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction, 2005. 100(15733243): p. 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, et al. , Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res, 2003. 5(12745503): p. 13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon JA, Carmody TP, Hudes ES, et al. , Intensive smoking cessation counseling versus minimal counseling among hospitalized smokers treated with transdermal nicotine replacement: a randomized trial. Am J Med, 2003. 114(12753879): p. 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor CB, Houston-Miller N, Killen JD, et al. , Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction: effects of a nurse-managed intervention. Ann Intern Med, 1990. 113(2360750): p. 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller NH, Smith PM, DeBusk RF, et al. , Smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. Results of a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med, 1997. 157(9046892): p. 409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dornelas EA, Sampson RA, Gray JF, et al. , A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counseling after myocardial infarction. Prev Med, 2000. 30(10731452): p. 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivarajan Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Christopherson DJ, et al. , High rates of sustained smoking cessation in women hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Initiative for Nonsmoking (WINS). Circulation, 2004. 109: p. 587–593. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115310.36419.9E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Salsman JM, et al. , Assessment of self-reported negative affect in the NIH Toolbox. Psychiatry Res, 2013. 206(1): p. 88–97. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. , Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment, 2011. 18(3): p. 263–83. 10.1177/1073191111411667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron IM, Cunningham L, Crawford JR, et al. , Psychometric properties of the BASIS-24(c) (Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale-Revised) Mental Health Outcome Measure. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract, 2007. 11(1): p. 36–43. 10.1080/13651500600885531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark MA, Rogers ML, Boergers J, et al. , A transdisciplinary approach to protocol development for tobacco control research: a case study. Transl Behav Med, 2012. 2(4): p. 431–40. 10.1007/s13142012-0164-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummings KM, Hyland A, Carlin-Menter S, et al. , Costs of giving out free nicotine patches through a telephone quit line. J Public Health Manag Pract, 2011. 17(3): p. E16–23. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182113871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ladapo JA, Jaffer FA, Weinstein MC, et al. , Projected cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med, 2011. 171(1): p. 3945 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, and Stead LF, Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2008. 168(18): p. 1950–60. 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawrence D and Kisely S, Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol, 2010. 24(4 Suppl): p. 61–8. 10.1177/1359786810382058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. , Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry, 2011. 10(2): p. 138–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metse AP, Wiggers J, Wye P, et al. , Efficacy of a universal smoking cessation intervention initiatied in inpatient psychiatry and continued post-discharge; A randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 2017. 51(4): p. 366–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hickman ND, K L and Prochaska JJ, Treating tobacco dependence at the intersection of diversity, poverty, and mental illness; A randomized feasibility and replication trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2015: p. 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peckham E, Bradshaw TJ, Brabyn S, et al. , Exploring why people with SMI smoke and why they may want to quit: baseline data from the SCIMITAR RCT. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 2016. 23(5): p. 282–9. 10.1111/jpm.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]