Abstract

Purpose:

Definitive therapy for prostate cancer (e.g., surgery, radiotherapy) often has side effects, including urinary, sexual, and bowel dysfunction. The purpose of this study was to test whether urinary, sexual, and bowel function contribute to emotional distress during the first two years post treatment, and whether distress may, in turn, decrease function.

Materials and Methods:

Participants were 1,148 men diagnosed with clinically localized disease who were treated with either surgery (63%) or radiotherapy (37%). Men’s urinary, sexual, and bowel function were assessed with the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) Emotional distress was assessed with the Distress Thermometer. Assessment time points were pre-treatment, 6 weeks, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-treatment. We used time-lagged multilevel models to test whether physical function predicted emotional distress and vice versa.

Results:

Men with worse urinary, bowel, and sexual functioning reported more emotional distress than others at subsequent time points. The relationships were bidirectional; those who reported worse distress also reported worse urinary, bowel, and sexual functioning at subsequent time points.

Conclusion:

To improve wellbeing in prostate cancer survivorship, clinicians, supported by practice and payer policies, should screen for, and facilitate treatment of side-effects and heightened emotional distress. These interventions may be cost-effective given that emotional distress can negatively impact functioning across life domains.

Cancer patients frequently experience emotional distress, not only when they are diagnosed and during treatment, but also into long-term survivorship.1, 2 Mental health issues have substantial human, medical care, and other financial costs,3, 4 and interventions to reduce emotional distress in cancer patients have been associated with decreases in care utilization and cost savings. 5, 6 Although emotional distress declines for most PCa patients over time, some tend to have high anxiety that does not decline to the level in the general population over time.7

Most of the 2.8 million PCa survivors in the U.S. have been treated with definitive therapy, typically surgery or radiotherapy. Men treated surgically often experience some degree of urinary incontinence, especially in the first year after treatment, and the majority experience erectile dysfunction even two years post-surgery.8 External beam radiation and brachytherapy are associated with erectile dysfunction and bowel pain and urgency.8, 9 To understand the magnitude of the impact of treatment side-effects on men’s lives, it is important to consider the impact of these side effects on emotional distress on PCa patients treated with definitive therapy.

In a cross-sectional study of Irish PCa survivors, worse urinary function was associated with depression, anxiety, and distress, and worse bowel function was associated with greater anxiety and distress. Sexual function was not associated with any of the psychological well-being outcomes.10 However, in a US sample, greater erectile dysfunction was associated with greater depression among survivors.11 In studies of general population samples, erectile dysfunction has been associated with emotional distress.12 Rather than conceptualizing distress as the result of declines in function, a third study hypothesized that psychological distress causes declines in function over time.13 They found that depression and anxiety were both associated with downward trends in sexual function over the three years post-diagnosis.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate whether urinary, bowel, and sexual function affect distress, and to also test whether distress influences function. Our study was prospective, controlling for baseline distress and function, and men were assessed at regular intervals for the two years following treatment. We assessed emotional distress and urinary, sexual, and bowel function prior to treatment (baseline) and at 6 weeks, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-treatment in men who had been treated either surgically or with radiotherapy (external beam radiation, brachytherapy, both external beam radiation and brachytherapy, or proton therapy).

METHODS

Data source and procedure

We used data from the Live Well Live Long! study, a prospective, multisite study of men diagnosed with clinically localized PCa. Men were recruited at, or shortly after diagnosis (prior to treatment) from two comprehensive cancer centers and three large group practices between 2010 and 2014. We approached 3,337 patients, of which 2,476 were consented, and 2,008 completed a baseline survey prior to treatment. We surveyed men again 6 weeks (n=1,679), 6 months (n=1,638), 12 months (1,580), 18 months (n=1,394), and 24 months (n=1184) post-surgery. We abstracted clinical information from medical records post-treatment (n=1,946). Data were used for 1,148 men who had baseline data and data for at least one follow-up time point and had been treated with surgery or radiotherapy. Those who completed a baseline questionnaire, but were not included in the multivariable models, were more likely to be Black than White (0.67, 95% CI = 0.36, 0.98, p<.001), unmarried (−0.60, 95% CI = −0.90, −0.31, p<.001), have lower educational attainment (−0.43, 95% CI = −0.77, −0.08), lower income (−0.59, 95% CI = −0.84, −0.35, p<0.001), worse baseline urinary (−1.78, 95% C = =3.27, −0.30, p=0.019) and worse sexual function (−3.49. 95% CI = −6.96, −0.02, p=0.049).

Measures

Urinary, sexual, and bowel function were assessed with function items of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-50).14 These items assess frequency of being affected by a treatment-related side effect during the previous 4 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. Function variables were handled differently depending on how they were used. If treated as outcomes, we used raw scores. Following recommendations by Bolger and Laurenceau, function predictor variables were separated into their within-person and between-person components.15

Emotional distress was assessed with the Distress Thermometer, an 11-point single-item visual analog scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). The Distress Thermometer has been validated and is a recommended distress screening tool for use in PCa patients,16, 17 with good specificity and sensitivity for detecting cancer-specific distress.18 When treated as an outcome, we used raw scores. When treated as a predictor, we calculated the within-person and between person components using the same method as for the function scores.

We controlled for baseline emotional distress and urinary, sexual, and bowel function in all models. Models were trimmed to only include additional covariates that were significantly associated with the outcome. In the untrimmed models (obtainable from the corresponding author) we controlled for type of treatment received (surgery vs. radiotherapy), whether participants also received androgen deprivation therapy, and D’Amico disease risk. Low-risk PCa was defined as clinical stage PSA ≤10 ng/ ml, Gleason score ≤6, and American Joint Commission of Cancer Staging (AJCC) less than cT2b.19 Intermediate-risk PCa was defined as PSA >10 and ≤20 ng/mL or Gleason 7 disease or AJCC cT2b. High-risk disease was defined as PSA >20 ng/mL or Gleason 8–10 disease or AJCC cT2c or higher.19 Demographic covariates were self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black, hereafter referred to as White and Black, and Hispanic); education attainment, a 14-level continuous variable ranging from having completed first grade to fourth year of graduate school; and a 9-level income variable ranging from <$5,000 to ≥$100,000, and age. It is possible that side effects are interpreted as signs of disease progression, in turn causing distress rather than side effects directly causing distress. To rule out this possibility we controlled for confidence in cancer control, assessed at each time point with a slightly adapted version of the cancer control subscale of Clark and colleagues’ multidimensional PCa quality of life scale.20 All categorical covariates were dummy coded and all covariates were grand mean centered.

Data Analyses

For descriptive purposes, we calculated mean levels of emotional distress at each time-point. We used a time-lagged multilevel model to test whether urinary, sexual or bowel function at one time point predicted emotional distress at the subsequent time point. An advantage of multilevel models is that cases are not deleted if they have missing data. All available data can be used for estimating effects. Observations over time (level 1) were clustered within individuals (level 2). We hypothesized both between- and within-person level 1 effects of function on distress. The first, captures the effects of individual differences in urinary function on distress over time: when individuals low in urinary function relative to others, experience more distress at the following time point relative to others. The second captures whether within individuals, worse function at an earlier time point compared to that person’s average function, predicts distress at a subsequent time point. We used this same analysis strategy to test whether distress predicted function. To keep the models as parsimonious as possible, we only controlled for baseline function and distress, time, and covariates that were associated with the outcome variable in the untrimmed multivariable models (p<.05). Predictors were entered as fixed effects, and an unstructured covariance structure was specified for all models.

RESULTS

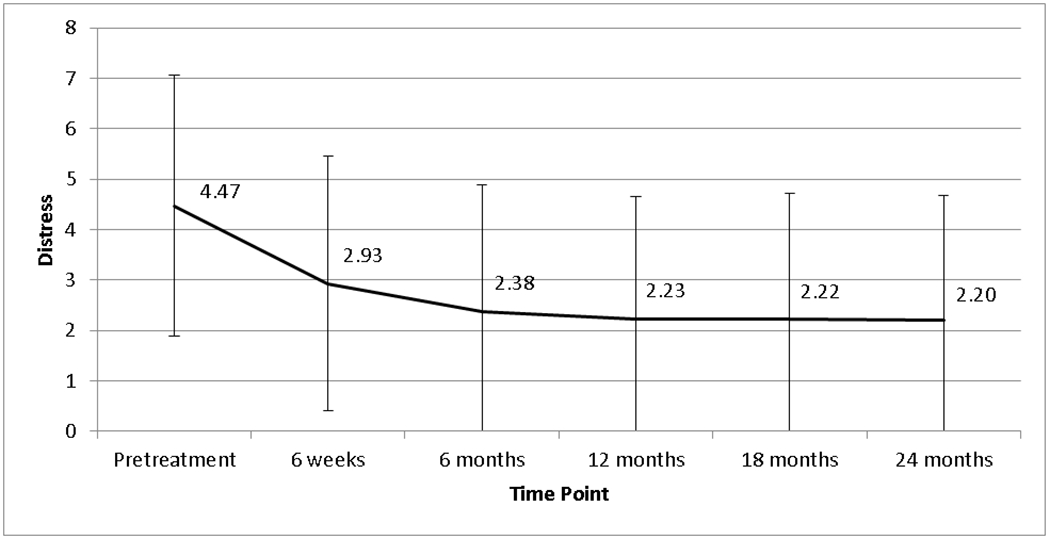

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Men were treated with radiotherapy (37%) or surgery (63%), and most had low (24%) or intermediate (56%) rather than high (20%) risk disease. Our sample was 80% White, 12% Black, and 7% Hispanic. Most had a college degree (55%) and were well off, with 52% earning $100,000 or more. Mean levels of distress at each time point are shown in the Figure. At baseline, 63% scored a 4 or greater on the distress scale (indicating possible clinical levels of distress), dropping to 38% at 6 weeks, 28% at 6 months, 27% at 12 months, 26% at 18 months and 27% at 24 months.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 1,148)

| Characteristic | N | % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment choice | ||

| Radiotherapy | 424 | 36.93 |

| Surgery | 724 | 63.07 |

| D’Amico risk | ||

| Low risk | 272 | 23.94 |

| Intermediate risk | 640 | 56.34 |

| High risk | 224 | 19.72 |

| Received hormone therapy | 179 | 15.59 |

| Baseline urinary function | 1,146 | 93.79 (10.61) |

| Baseline sexual function | 1,123 | 51.64 (25.74) |

| Baseline bowel function | 1,148 | 93.09 (8.47) |

| Baseline distress | 1,148 | 4.47 (2.59) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 924 | 80.49 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 140 | 12.20 |

| Hispanic | 84 | 7.32 |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 28 | 2.45 |

| High school | 325 | 28.43 |

| Some college/trade | 166 | 14.52 |

| ≥ College | 624 | 54.59 |

| Income | ||

| < $25,000 | 59 | 6.02 |

| $25,000 - $49,999 | 118 | 12.05 |

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 148 | 15.12 |

| $75,000 - $99,999 | 145 | 14.81 |

| ≥ $100,000 | 509 | 51.99 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 466 | 40.70 |

| Employed | 679 | 59.30 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Not married/cohabitating | 168 | 14.65 |

| Married/cohabitating | 979 | 85.35 |

| Age | 1,148 | 62.97 (7.98) |

Note: Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding. Income and education were treated as continuous variables in the multivariable models.

Figure.

Mean distress at each time point with standard deviation bars

In the model testing whether function predicts emotional distress (Table 2), between-person effects of urinary, sexual, and bowel function on distress were all significant. On average, individuals with worse urinary (b = −0.03, Standard Error (SE) = 0.004, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = −0.03, −0.02, p<0.001), sexual (b = −0.01, SE = 0.003, 95% CI = −0.02, −0.007, p<0.001), and bowel (b = −0.07, SE = 0.008, 95% CI = −0.08, −0.05, p<0.001) function were more emotionally distressed at follow-up time points compared to those with better function. None of the within-person effects of function on distress were significant. Greater confidence in cancer control at a previous time point was associated with lower emotional distress (b = −0.02, SE = 0.002, 95% CI = −0.02, −0.01, p<0.001) at the following time point. Higher baseline distress and higher baseline bowel function were associated with greater distress over time (b = 0.27, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.23, 0.31, p < 0.001; b = 0.02, SE = 0.007, 95% CI = 0.004, 0.03, p = 0.013, respectively). Older participants were also less distressed (b = −0.05, SE = 0.008, 95% CI = −0.06, −0.03, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Effects of urinary, sexual, and bowel function on distress (N = 1,146)

| Parameter | b | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Within-person urinary functiona | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.569 |

| Between-person urinary functiona | −0.03 | 0.004 | −0.03 | −0.02 | <0.001 |

| Within-person sexual functiona | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.314 |

| Between-person sexual functiona | −0.01 | 0.003 | −0.02 | −0.007 | <0.001 |

| Within-person bowel functiona | 0.01 | 0.004 | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.070 |

| Between-person bowel functiona | −0.07 | 0.008 | −0.08 | −0.05 | <0.001 |

| Cancer controlb | −0.02 | 0.002 | −0.02 | −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Baseline distressb | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Baseline urinary functionb | −0.002 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.650 |

| Baseline sexual functionb | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.003 | 0.008 | 0.332 |

| Baseline bowel functionb | 0.02 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.013 |

| Time | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.438 |

| Educationb | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.242 |

| Ageb | −0.05 | 0.008 | −0.06 | −0.03 | <0.001 |

Note: SE = standard error

Predictor variables were time-lagged

Covariates were grand-mean centered

In the reversed models with which we tested whether emotional distress affects function (Tables 3–5), those higher in emotional distress at one time point experienced worse urinary (b = −2.51, SE = 0.21, 95% CI = −2.92, −2.09, p<0.001), sexual (b = −2.27, SE = 0.29, 95% CI = −2.84, −1.70, p<0.001), and bowel (b = −1.11, SE = 0.11, 95% CI = −1.32, −0.91, p<0.001) function 6 months later compared to those lower in emotional distress. There was also a within-person effect of more emotional distress on worse urinary function (b = −0.19, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = −0.36, −0.02, p=0.029), suggesting that individuals who experienced more distress than their average at one time point experienced worse urinary function at the subsequent time point. Associations between covariates and function are reported in Tables 3–5.1

Table 3.

Effect of distress on urinary function (N = 1,137 )

| Parameter | b | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Within-person distressa | −0.19 | 0.09 | −0.36 | −0.02 | 0.029 |

| Between-person distressa | −2.51 | 0.21 | −2.92 | −2.09 | <0.001 |

| Cancer controlb | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.008 |

| Baseline distressb | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 1.08 | <0.001 |

| Baseline urinary functionb | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.35 | <0.001 |

| Time | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Ageb | −0.26 | 0.06 | −0.37 | −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy,c | 9.37 | 1.00 | 7.41 | 11.33 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Blackc | −3.62 | 1.19 | −5.95 | −1.29 | 0.002 |

| High riskc | −3.64 | 0.97 | −5.54 | −1.75 | <0.001 |

Note: SE = standard error; we controlled for recruitment site although statistics for that effect are not reported as there is no meaningful referent group

Predictor variables were time-lagged

Covariates were grand-mean centered

Referent groups were surgery, non-Hispanic white, low-risk

Table 5.

Effect of distress on bowel function (N = 1,148)

| Parameter | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Within-person distressa | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.685 |

| Between-person distressa | −1.11 | 0.11 | −1.32 | −0.91 | <0.001 |

| Cancer controlb | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Baseline distressb | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| Baseline bowel functionb | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.19 | 0.16 | 0.879 |

| Ageb | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.13 | −0.02 | 0.005 |

| Radiotherapyb,c | −2.81 | 0.43 | −3.66 | −1.96 | <0.001 |

Note: SE = standard error

Predictor variables were time-lagged

Covariates were grand-mean centered

Referent group was surgery

DISCUSSION

During the two years after being treated with surgery or radiotherapy, men with worse urinary, sexual, and bowel function compared to their counterparts experienced more emotional distress at subsequent time-points. The reverse relationship was also true; being more emotionally distressed than one’s counterparts predicted worse function at a subsequent time-point. This bidirectional relationship likely affects PCa survivors because of the risk of urinary, sexual, and bowel side-effects from PCa treatment, but is not specific to PCa survivors. The relationship between depression and sexual dysfunction has been shown to be bidirectional in general population samples.21 Anxiety and depression are also related to bowel function.22 While we might easily understand how living with side-effects of PCa treatment could be distressing, it is less obvious how distress might cause decrements in physical functioning. There is evidence that emotional distress influences people’s perceptions of the severity of their physical symptoms.23 Emotional distress could also influence urinary, bowel, and sexual function via physiological pathways24, 25 compounding the effects of treatment side effects. Also, some medications used to treat depression or anxiety such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, use of which we did not assess, can cause sexual and bowel dysfunction.

We found across-the-board between-person effects both functioning and distress, but only a statistically significant within-person effect of distress on urinary function, although the within-person effects of distress on sexual function was marginally significant. The within-person effects capture within-person variability around an individual’s mean. We might expect variation in distress and functioning to cycle relatively rapidly, say over days or weeks, rather than months. As we only assessed men every six months we likely missed capturing any existing relationship between fluctuations in distress and corresponding changes in functioning, or vice versa.

Levels of emotional distress in our sample followed the general pattern reported previously in the literature, where emotional distress is highest at diagnosis and declines afterwards.7, 18, 26 Typically, about a quarter to a third of men experience clinically significant emotional distress and can continue to experience psychological issues throughout survivorship. 7, 27 Our rates were somewhat higher, in particular at baseline, perhaps because the distress thermometer may overestimates clinically significant distress.28

Limitations, strengths, and implications

The Distress Thermometer is a recommended screening tool for emotional distress in cancer survivors, but longer scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale are the gold standard for identifying patients suffering from anxiety or depression. If the goal is to identify precisely what levels of dysfunction may result in clinically significant distress, a more psychometrically robust measure of emotional distress should be used. Also, while we controlled for baseline emotional distress, it would informative to be able to control for trait anxiety, neuroticism and comorbid anxiety and depression in order to understand how much of the association between urinary, bowel, or sexual functioning and distress are attributable to person differences in these characteristics. However, knowing the extent to which either is attributable to personality traits or baseline psychological issues does not radically change the approach to intervention. We may have underestimated the strength of the relationships between function and distress due to relatively higher attrition among participants with worse urinary and sexual function (although not higher distress), and who are the most likely to be underserved (e.g., unmarried, minority). Our findings underline the importance for screening for distress, monitoring for treatment side-effects, and providing interventions for both emotional distress and side-effects when indicated. Finally, our results are important for clarifying the causal relation between side-effects-related physical functioning and emotional distress. Our study provides the strongest evidence to date that the relationship between the two is bidirectional.

It has been argued that reducing the emotional burden of cancer is feasible and cost effective.29 It’s not simply adequate to monitor cancer patients for distress and physical quality of life issues 30; intervention needs to be accessible. While this might include greater investment in psychosocial care, in the case of PCa care, it also means mitigating survivors’ treatment side-effects. As most PCa patients have excellent prognosis, the primary long term sequelae of the disease are side effects from treatment. Two health policy changes that could improve survivors’ well-being are increased access to health care coverage for treatments for erectile dysfunction and better access to psycho-oncological care both at diagnosis and after treatment for those who have high distress. Also, given the likely bidirectional nature of the relationship between side effects and emotional distress it makes sense for facilities that have traditionally not incorporated psycho-social care into their practice to consider doing so.

Table 4.

Effect of distress on sexual function (N = 1,103)

| Parameter | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Within-person distressa | −0.24 | 0.13 | −0.50 | 0.01 | 0.059 |

| Between-person distressa | −2.27 | 0.29 | −2.84 | −1.70 | <0.001 |

| Cancer controlb | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.005 |

| Baseline distressb | 0.93 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 1.37 | <0.001 |

| Baseline sexual functionb | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Time | 1.48 | 0.17 | 1.15 | 1.82 | <0.001 |

| Educationb | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.92 | 0.003 |

| Ageb | −0.47 | 0.08 | −0.64 | −0.31 | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapyb,c | 8.80 | 1.50 | 5.85 | 11.75 | <0.001 |

| Hormone therapyb,c | −9.08 | 1.77 | −12.54 | −5.62 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate riskc | −4.29 | 1.28 | −6.80 | −1.79 | 0.001 |

| High riskc | −9.66 | 1.69 | −12.98 | −6.34 | <0.001 |

Note: SE = standard error; we controlled for recruitment site although statistics for that effect are not reported as there is no meaningful referent group

Predictor variables were time-lagged

Covariates were grand-mean centered

Referent groups were surgery, no hormone therapy, and low-risk

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institutes (R01#CA152425).

Footnotes

Men on active surveillance were not included in the analyses for this paper; however, the bi-directional relationship between function and distress holds for this group as well. There were significant between-persons effects of urinary, sexual and bowel function on distress (p<0.034). There were significant between-person effects of distress on urinary, sexual, and bowel function (p≤0.001), and an additional within-persons effect for higher distress associated with better bowel function (p=0.028).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Holmberg L et al. : Long-term distress after radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in prostate cancer: A longitudinal study from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol., 64: 920–928, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G et al. : Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology, 23: 121–130, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luppa M, Heinrich S, Angermeyer MC et al. : Cost-of-illness studies of depression. A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord, 98: 29–43, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon GE: Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry, 54: 208–215, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson JSA, Carlson LE, Trew ME: Effect of group therapy for breast cancer on healthcare utilization. Cancer Pract, 9: 19–26, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabariego C, Brach M, Herschbach P et al. : Cost-effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral group therapy for dysfunctional fear of progression in cancer patients. Eur J Health Econ, 12: 489–497, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Janssens ACJW et al. : Anxiety and depression after prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment: 5-year follow-up. Br. J. Cancer, 94: 1093–1098, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA et al. : Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med, 375: 1425–1437, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pardo Y, Guedea F, Aguiló F et al. : Quality-of-life impact of primary treatments for localized prostate cancer in patients without hormonal treatment. J Clinical Oncol, 28: 4687–4696, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharp L, O’Leary E, Kinnear H et al. : Cancer-related symptoms predict psychological wellbeing among prostate cancer survivors: results from the PiCTure study. Psychooncology., 25: 282–291, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ: The Association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8: 560–566, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA et al. : The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: Cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom. Med, 60: 458–465, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Punnen S, Cowan JE, Dunn LB et al. : A longitudinal study of anxiety, depression and distress as predictors of sexual and urinary quality of life in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int, 112: E67–E75, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS et al. : Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology, 56: 899–905, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolger N, Laurenceau JP: Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L et al. : Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer, 82: 1904–1908, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Fort Washington, PA, vol. 2014, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers SK, Zajdlewicz L, Youlden DR et al. : The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. Psychooncology., 23: 195–203, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB et al. : Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA, 280: 969–974, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS et al. : Measuring patients’ perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med. Care, 41: 923–936, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlantis E, Sullivan T: Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9: 1497–1507, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H: Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: A meta‐analytic review. Psychosom. Med, 65: 528–533, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennebaker JW: The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovallo WR: Stress and health: Biological and psychological interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorn BH, Montgomery H, Pieper K et al. : Urinary incontinence and depression. The Journal of Urology, 162: 82–84, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dale W, Bilir P, Han M et al. : The role of anxiety in prostate carcinoma: a structured review of the literature. Cancer, 104: 467–478, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halbert CH, Coyne J, Weathers B et al. : Racial differences in quality of life following prostate cancer diagnosis. Urology, 76: 559–564, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell AJ: Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J. Clin. Oncol, 25: 4670–4681, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson LE, Bultz BD: Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: Making the case for economic analyses. Psychooncology., 13: 837–849, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingworth W, Metcalfe C, Mancero S et al. : Are needs assessments cost effective in reducing distress among patients with cancer? A randomized controlled trial using the Distress Thermometer and Problem List. J. Clin. Oncol, 31: 3631–3638, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]