Abstract

Background

Alcohol is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide. Rates of alcohol abuse in Moshi, Tanzania, are about 2.5 times higher than the Tanzanian average. We sought to qualitatively assess the perceptions of alcohol use among injury patients in Moshi, including availability, consumption patterns, abuse, and treatments.

Methods

Participants were Emergency Department injury patients, their families, and community advisory board members. Participants were included if they were ≥18 years of age, a patient or patient’s family member seeking care at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center Emergency Department, Moshi, Tanzania, for an acute injury, clinically sober at the time of enrollment, medically stable, able to communicate in Swahili and consented to participate. Focus group discussions were audiotaped, transcribed, translated, and analyzed in parallel using an inductive thematic content analysis approach. Resultant themes were then reanalyzed to ensure internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity.

Results

Fourteen focus group discussions, with a total of 104 participants (40 patients, 50 family members, 14 community advisory board members), were conducted. Major themes resulting from the analysis included: 1) Early/repeated exposure; 2) Moderate use as a social norm with positive attributes; 3) Complications of abuse are widely stigmatized; and 4) Limited knowledge of availability of treatment.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, among our unique injury population and their families, despite the normalization of alcohol-related behaviors, there is strong stigma toward complications stemming from excess alcohol use. Overall, resources for alcohol treatment and cessation, although broadly desired, are unknown to the injury population.

Keywords: Alcohol, Qualitative, Tanzania, Perceptions

Introduction

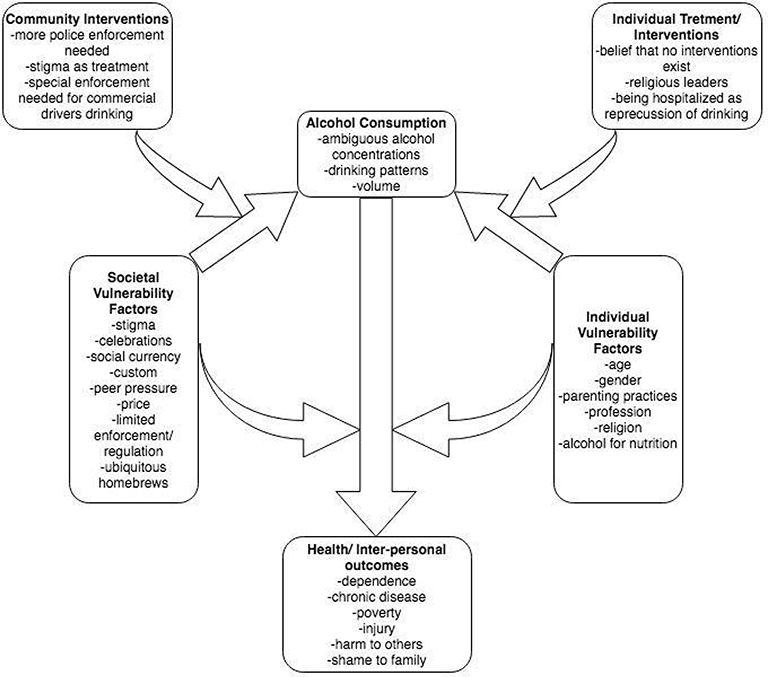

Alcohol is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide (WHO, 2014; IHME, 2015). Alcohol-attributable injury is also responsible for 5% of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) (WHO, 2018). In Tanzania, alcohol has been associated with injuries- especially road-traffic injuries (Staton et al., 2018; Diamond et al., 2018; Boniface, 2016; Staton, 2016). As much as 26% of injury patients presenting to a hospital in Tanzania tested positive for alcohol or drugs (Mundenga et al., 2019). Alcohol’s effect on health outcomes involves the interplay of a number of societal and individual factors (WHO, 2014; Gilmore, 2016). Factors that influence alcohol consumption and the subsequent alcohol’s effect on health outcomes have been shown in the Conceptual Model of Alcohol Consumption and Health Outcomes designed by the WHO (WHO, 2014). This model suggests that societal and individual vulnerability factors influence alcohol consumption and alcohol-related outcomes. Societal vulnerability factors include level of development, culture, drinking context, and alcohol production, distribution, and regulation. Individual vulnerability factors include age, gender, familial factors, and socio-economic status. These factors impact volume and pattern of alcohol consumption and thus chronic and acute health outcomes, such as injuries. Although this model was developed to be generalizable across cultures, translating it for specific communities can support the development of tailored interventions. Furthermore, a culturally translated model can inform subsequent studies about alcohol use in this context with the aim of reducing the societal and individual factors impacting alcohol consumption and related outcomes (Rehm, 2010; Blas, 2010).

The Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania has high rates of alcohol consumption compared to other Tanzanian regions (Mitsunaga, 2008; Carlson, 1993; McCall, 1996). The proportions of the population in Moshi with harmful use of alcohol or alcohol dependence (CAGE 2–4) were found to be 7.7% in women and 22.8% in men, compared to 1.9% in women and 9.3% in men nationally (Mitsunaga, 2008; WHO, 2014). Although previous work has quantitatively addressed risk factors and prevalence of harmful alcohol use in Moshi (Mitsunaga, 2008), there is no Tanzania-specific qualitative study trying to understand the perceptions of alcohol use behavior and its societal/individual influences in a high-risk population, such as injury patients.

Therefore, to explore societal factors and individual underpinnings that influence alcohol consumption and how alcohol use influences the burden of injuries in this setting, we need to understand the perceptions of alcohol use and alcohol-related behaviors within this high-risk injury population. We have chosen a specific population (injury patients) that is highly affected by alcohol use and whose perceptions about the phenomena will guide future development and tailoring of interventions. Using this conceptual model to guide our injury population’s experience with alcohol could guide potential mediators or moderators of alcohol use. This study aims to qualitatively explore the perceptions of societal and individual factors related to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related outcomes by investigating injury patients, their families, and community members in Moshi, Tanzania.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research, and the Duke University Medical Center; these 3 Ethics review committees are required for Duke collaborators to conduct research with Tanzanian colleagues in the KCMC setting. All participants took part in an informed consent process approved by the Duke and Tanzanian ethics committees before data collection. All transcripts, audiotapes, and related data are located in an Internet–based database behind a university firewall.

Study Design

This study used semi-structured focus groups based on the grounded theory model. This method allows for the development of the framework of a theoretical model proposal (Corbin, 1990). This approach led to focus group questions about participants’ perceptions regarding alcohol use, alcohol-related behavior, availability, complications, and treatment in their community (Table 1, Appendix A).

Table 1:

Sample Focus Group Script Informed by WHO Conceptual Model

| WHO Conceptual Model | Example Factor | Example FG Question |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Factors | Age | When are people in Moshi first offered alcohol? |

| Familial factors | How do children get alcohol? | |

| Societal Factors | Culture | What are the perceptions associated with moderate alcohol use? |

| Alcohol Consumption | Volume | Are people open about their alcohol use; Do they tell their doctor what amount of alcohol they drank without exaggerating or reducing the amount? |

| Health Outcomes | Chronic | A ‘drinking problem’ is when you drink large amounts of alcohol, must have alcohol in the morning, you can’t go more than a few days without alcohol, or when you have shakes or seizures when you don’t drink alcohol. Are there any friends or family you know that have had a drinking problem? |

Setting

This study took place in the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) in Moshi, Tanzania. KCMC is a referral hospital for the larger Kilimanjaro Region. The KCMC Emergency Department (ED) sees about 2,000 injury patients annually, of whom approximately 30% are positive for alcohol on arrival (Staton, 2016). KCMC is a referral hospital in Northern Tanzania which can be free with referral from a local clinic or for a nominal fee if not referred. KCMC is the regional training center and has the highest level of clinical trauma patient management capacity in the Kilimanjaro region.

Participants

Focus group participants were a convenience sample of ED injury patients, their families, and volunteer community advisory board (CAB) members. Patients and their family members were identified in the KCMC ED waiting or treatment areas. Injury patients were included in the focus groups if they were ≥18 years of age, seeking care at KCMC for an acute injury, clinically sober by breathalyzer at the time of enrollment, medically stable, able to communicate in Swahili or English, and consented to participate. When the desired number of injury patients were enrolled, these focus groups were scheduled. Injury patients were selected because this population has been shown to have high alcohol use and they are the target of a future intervention. (Staton, 2017). Family members and CAB members were enrolled to adequately assess our injury patient’s direct community, and their perceptions toward alcohol use. Family member focus group participants were family members of a patient enrolled in the study who also agreed to participate and spoke Swahili or English.

Research nurse facilitators attended a CAB meeting in August 2016 and approached members ≥18 for enrollment in the study. The KCMC CAB consists of adults who understand research and have advised investigators on pertinent research questions, cultural norms, and cultural acceptability of interventions, treatments, and research protocols. While these CAB members might not represent a non- medically savvy general population, they do as closely as possible represent an injury patient’s community as they are part of the KCMC community and patients.

Focus Group Procedures

When 5‒10 eligible patient or family member participants were recruited, focus groups were scheduled. Focus groups occurred in a small quiet room near the ED where participants could freely discuss their thoughts and opinions. No members of the treatment team were in the room, and patient focus groups were separate from family member focus groups. Focus groups lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Focus groups were conducted by two trained, bilingual female research nurses at KCMC. All focus groups were conducted in Swahili. Both research nurses have over 10 years of experience conducting focus groups among similar patient populations. Focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed for formal qualitative analysis within days following the focus group.

CAB focus groups consisted of 5‒10 CAB members. Focus group procedures were the same as those for patients and family members.

After transcription, each discussion was translated from Swahili to English. Debriefing sessions with focus group facilitators assessed for potential cultural misinterpretations and annotated the translation for American English comprehension. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection in order to improve focus group questions and determine when saturation was reached. Focus groups among each population group continued until thematic saturation was reached. Thematic saturation occurred when no new themes developed from focus group analysis (Guest, 2006). No participants refused to take part in the focus groups or asked to leave during the research process.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were analyzed using a deductive thematic content analysis approach, having the Conceptual Model of Alcohol Consumption as a framework for the coding process. This approach was chosen because there was no previous research or framework analyzing perceptions of alcohol use in this setting (Braun, 2006). We pre-defined the analysis categories based on the conceptual model, coding the interviews according to the following topics: societal vulnerability factors, individual vulnerability factors, alcohol consumption, health/interpersonal outcomes, and alcohol-related interventions. The analysis was iterative throughout the study, which allowed emerging themes to be explored in later focus groups (Riessman, 2005).

We analyzed transcripts according to four steps: (1) Interpreted a sense of the transcript through multiple readings; (2) Identified concept categories and extracted the ones that were relevant for pre-specified model-driven categories; (3) Integrated different concept categories into emerging themes; and (4) Aggregated emerging themes under the categories proposed by Conceptual Model of Alcohol Consumption. We reported the content analysis results by showing the coding tree with codes and emerging themes mapped to each pre-specified category are reported. Also, an adapted version of the Conceptual Model of Alcohol Consumption was created.

Coding

All transcripts were coded by researchers (DE and BJM) using a content analysis approach (Corbin, 1990). The focus groups were coded individually and then analyzed. DE and BJM then compared coding with an author (JRNV) with qualitative research expertise. All discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data saturation, whereby no new or relevant emerging themes arose, was achieved by the time data had been collected from 14 focus groups. Emerging themes were validated by the Tanzanian research team, who reviewed the evolving thematic codes and resulting narratives (Corbin, 1990).

Results

A total of 14 focus groups were conducted (6 patient, 6 family members, 2 CAB) with 104 participants (40 patients, 50 family members, 14 CAB members). Demographic information is not presented here in the interest in maintaining respondent confidentiality. In analyzing these focus groups, common themes emerged across the three disparate groups. These themes represent different perceptions of factors influencing alcohol use within the population that affect alcohol consumption and ultimately one’s health and wellness (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1:

Conceptual model of alcohol consumption and health outcomes in Moshi, Tanzania

Table 2:

Summary of Themes Regarding Alcohol Use

| Factor | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual vulnerability factors | ||

| Age issues | - Early start with alcohol use - Parenting influences to early start - Availability of alcohol for young adults |

|

| Sex-based access | - Easier access to males - Cultural tradition determining sex differences - Acceptance of male alcohol use |

|

| Alcohol value | - Difficult jobs require drinks and not thinking - Alcohol brings energy - Young people work to get money to buy alcohol - Alcohol for nutrition |

|

| Societal vulnerability factors | ||

| Stigma | - Peer pressure for drinking - Negative perceptions toward alcohol users - Devaluation of alcohol addiction - Relativization of alcohol use stigma |

|

| Celebrations, social currency, and cultural custom | - Alcohol as part of traditional celebrations - Societal custom of drinking - Tastes when buying alcohol |

|

| Availability and social relevance | - Alcohol used as a social trade - Alcohol as the motive for social gatherings - Ubiquitous homebrews - Cheap and accessible for young adults |

|

| Limited enforcement/regulation | - Impossible to be regulated - Challenges to enforcement - Perception of lack of regulation |

|

| Family alcohol availability | - Alcohol as a family value - Alcohol is available in the home and through parents/social actors - Children buy alcohol for their parents - Alcohol is made in the home so children are around it |

|

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Ambiguous alcohol concentrations | - Accepted volume related to harm to others - No specified metric for high alcohol use |

|

| Drinking patterns | - Reduction of alcohol use as successful outcome - Custom to drinking and driving - Alcohol as a motivator for work |

|

| Normalization of alcohol use | - No perceived need for help - Unwillingness to disclose or seek support - Alcohol as a regular part of daily life - Minimization of alcohol use - Alcohol seen as medicine or food |

|

| Health/interpersonal outcomes | ||

| Dependence | - Alcohol dependence as the main health outcome - Alcohol dependence influencing daily activities - Stigma to alcohol addiction |

|

| Poverty | - Alcohol leads to poverty and social degradation | |

| Harm to others | - Alcohol becomes problematic when it leads to physical harm to others - Alcohol becomes problematic when it leads family embarrassment - Family problems caused by stigma |

|

| Harm to self | - Higher exposure to injury - Difficulties with activities of daily living |

|

| Alcohol-related interventions | ||

| Community interventions | - Stigmatization as a community intervention - Lack of awareness of community intervention possibilities - Enforcement as potential intervention |

|

| Individual treatment | - Treatment as a synonym to stop drinking - Lack of awareness of treatment possibilities - Lack of awareness of the benefits to seeking treatment for alcohol - People only seek treatment if they experience adverse effects |

Individual Vulnerability Factors

Regarding individual vulnerability factors, the common themes involved age and its relationship with access to alcohol. Most participants in all focus groups reported an early start or early experience with alcohol, mostly at home and influenced by parents, but also in social gatherings or in alcohol outlets, as expressed by one participant:

“In previous periods, at least the age of eighteen years is when people started taking or being given alcohol. But right now a person’s age does not matter. You find even small children even in the presence of visitors, takes a little alcohol, and starts drinking. This presumption starts creating an environment of liking alcohol because they start getting used to it.”

Sex issues were also predominant in the participants responses. Being male was reported with easier access and more social acceptance to alcohol use: “Only the father of the house, the grandfather, or others who have inherited the elders’ name in the clan may drink; Chagga women are not allowed to even touch the mug used to distribute alcohol.” “Men can go to the bars and start drinking alcohol and spend the whole day in there from the morning at 8 am to night. Also men can sit anywhere even at the counter, but for a woman, she has to go and hide herself somewhere within the bar premises to drink beer or any type of alcohol.”

Societal Vulnerability Factors

Stigma toward alcohol use was the main societal vulnerability factor identified in the participants’ responses. This was seen through the stereotyping of people who drink certain alcohol, the assumption that alcohol abusers pressure others to drink excessively, and the devaluation of those with alcohol addiction. One participant explained how an alcoholic was ostracized from society due to this stigma: “He can be isolated. Because when he is drunk what can you advise him? He will be isolated because he has been useless and he has lost his respect in the community.”

Another participant elaborated on this stigma: “[...] the person who drinks excessively I consider him to be not ok mentally and is a failure in life because if you want to lead a good life and your mind to work properly you will not drink excessively because you might fall down and get hurt and you will put your family in trouble because the person might be working and the family depends on him to take care of it and to send kids to school, but because this person drinks excessively he will not be able to do work.”

However, the presence of stigma seemed to be relativized in relation to a concept of normal usage of alcohol, which diverged in format and content. Alcohol is embedded in some traditional celebrations, as reports a family member: “Another reason is that big celebrations […] without alcohol are not real celebrations.” Other narratives about customs toward drinking were “one for the road” where everyone has one more drink while they are leaving a gathering, or the widely known use for alcohol to “remove the lock,” i.e. to overcome the effects of the previous night’s drinking.

It was also common to narratives about parents asking children to purchase alcohol from stores, which suggests an easy access to alcohol even in early ages highlighting the limited alcohol regulation or enforcement practices. One family member explains: “Alcohol availability to young adults is very easy, he/she is an adult so is able to get money to buy and drink alcohol, and therefore it is very easy to get alcohol.” Additionally, participants reported that in some families, everyone in the family “drank homemade alcohol for its price and nutritional value.”

Families appeared to adopt a liberal use of alcohol with or around children and even use children to buy alcohol, where they are offered tastes with local outlets: “When I was young, my dad had a habit of sending me to buy him alcohol and in past years the alcohol vendors used to like it so much when a customer would buy alcohol to give him/her to taste. My dad used to give me stern warnings that if I am given alcohol, I should not taste it. Hence if he sends me to buy a liter of alcohol he would give me an extra bottle so that if I was given extra alcohol to taste, I would put it there. So when I arrived home, he would inspect how much alcohol I had brought. He would ask “he asked you to taste the alcohol, where did you keep it? I want to see how much he gives you to taste. “Therefore he would measure what I had been given in order to substantiate my claims. He always followed up with me. But nowadays when children are given alcohol to taste they gulp all of it. And when you are older like 15 or 16 years old then you meet other boys your age and you start drinking together.”

According to the participants stories, alcohol was also highly valued as social currency to facilitate gatherings and relationships at times. For example: “In the places that they prepare the local beer called ‘gongo’ it’s easy to go there and help make the beer. The laborers can taste the beer, so that’s how they drink. They drink the gongo as part of their wages, and so when they come out of that job they’re already used to drinking.” Homebrews were specifically cited as problematic for providing cheap alcohol availability to those unable to afford store-bought alcohol. With ubiquitous homebrews, regulation on sales of alcohol is perceived to be impossible, and some of the policies that aim to limit drunk driving and other dangerous alcohol-related behaviors lack enforcement.

Alcohol Consumption

The participants were consistent in reporting an ambiguous definition of an acceptable consumption pattern. What is considered average drinking consumption is described by one participant as the amount that an experienced drinker, who does not cause problems for others, consumes:

“Average drinkers are ok because they don’t drink so much as to cause problems.” “I can see for those who are average drinkers they are right because they don’t drink so much as to cause problem to him because he is drinking and he is experienced and if he cannot increase the amount then there is no effect and it is ok.”

Finally, the reports suggested a normalization of alcohol consumption, as part of the regular life: “[...] some elderly or mothers use alcohol as food or even disguised as medication.” However, it was possible to notice a minimization of the alcohol problem in the society, with repeated quotes about alcohol users not perceiving the need for help (treatment), or not reporting the correct amount of alcohol use, as one patient highlights: “I might say I use one or two bottles of alcohol but I will never tell the doctor that I use four or five bottles of alcohol.”

Health/Interpersonal Outcomes

Alcohol dependence was the major health outcome of alcohol consumption reported by the participants. Similar to a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnosis, it was defined as an increased tolerance, experience of withdrawal symptoms, and a level of alcohol use that influences daily life. Examples of dependence were seen in a person who “cannot sleep without alcohol” or a doctor who was “unable to attend patients in the hospital without going to the bar to drink alcohol” or those who say “that if they are not drunk they cannot work and the body becomes weak.” These definitions did not include some other aspects of a DSM diagnosis, such as a disinterest in activities that were once important, being sick from drinking, or an attempt to reduce drinking.

Throughout the focus groups, drinking was termed problematic when it led to physically harming others or neglecting family responsibilities. “Those drinking alcohol excessively... are the ones who cause car accidents, unintentionally killing others because they drink and drive. They cannot even maintain their own families.” Individually, respondents associated alcohol with poverty, social degradation, and injury, as described in the quote:

“Those who drink alcohol can only focus on drinking alcohol, and alcohol costs much and therefore it can lead to poverty.” “There will be no respect to such people. Most of them you will find even the wife has run away from him. He has loss of appetite, and so it’s affecting his health. A person like this we take him as an alcoholic person.”

Alcohol Intervention

Throughout the focus groups the term “treatment” was used synonymously with “stopping drinking,” but all members reiterated that they were not aware of places to receive treatment. Treatment was mostly described as giving personal advice or social support. Many were unaware of advanced treatment availability and what its benefits might be. As the following participant explains: “The treatment is just to give them advice to reduce the amount of alcohol they take, but it’s not possible to stop completely. Also, it’s better for people to pray for the person to stop drinking, but I have never seen a specific place where people who drink excessively are treated.”

Stigmatizing heavy drinkers was one community intervention referenced to reduce alcohol consumption. A common belief was that community ostracization of a person who drank excessively could lead to limited alcohol consumption. “There is nothing you can do to advise an alcoholic person because the community has seen him like a mad person. But you must take him very slowly until he reforms himself. The community sees an alcoholic person who has decided to reduce drinking from ten bottles to one as a big improvement.” Besides this relationship with community perceptions, no existing community interventions were referenced.

These themes associated with the perceptions of alcohol use in Tanzania reflected those of the Conceptual Model of Alcohol Consumption. Figure 1 shows the factors which support this sociocultural interpretation of effects on alcohol consumption, as tailored to the Tanzanian population.

Discussion

According to the WHO, drinking patterns in the African region are the second worst worldwide (WHO, 2014). Our evaluation of injury patient’s perceptions of alcohol use in Moshi showed a complex interaction of individual and societal vulnerability factors, alcohol consumption, interventions, and health and interpersonal outcomes. This interplay of factors has been previously proposed (Gilmore, 2016; WHO, 2014); however, our study provides insight into the specific factors affecting the injury population with which we will target future interventions.

Individual Vulnerability Factors

Many individual factors influence alcohol consumption and risk for alcohol use disorders. The drinking culture and context in Tanzania results in exposure from an early age and normalization of alcohol-related behaviors (Ao, 2011; Kilonzo, 2004; Mbatia, 2009). This is concerning because early onset of alcohol consumption is associated with lifetime Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) (Dawson, 2008; Chou, 1992; Grant, 1997; Kraus, 2000; Jackson, 1997).

Societal Vulnerability Factors

Perceived common societal vulnerability factors for the Tanzanian population were stigma, celebrations, alcohol as a social currency, ubiquitous homebrews, and regulation and enforcement of alcohol use. Focus groups revealed a strong stigma against those who abuse alcohol to the point of affecting their family or community; however, the way in which this stigma presented itself varied by individual factors such as sex and age. This is particularly relevant as evidence from both high- and low-income settings suggests that social stigma influences treatment-seeking behavior and should be taken into consideration when implementing treatment strategies (Ao, 2011; Jarvis, 1992; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2006; Sorsdahl, 2012). Similar to other settings (Fitts et al., 2018), ubiquitous homebrews in Tanzania limit or circumvent regulations and increase the difficulty with enforcement of laws against alcohol use.

Health/Interpersonal Outcomes

The perception of Alcohol Dependence as the worst outcome is a concerning finding. Most of the alcohol-related harm occurs among those with ‘Harmful and Hazardous Use’ as opposed to those with Alcohol Dependence (SAMHSA, 2015; O’Flynn, 2011). Therefore, the perception that alcohol dependence is the most severe form of alcohol use disorder potentially increases the stigmatization and reduces the chance of recognition of an AUD (Weine et al., 2016). Alternatively, our focus groups did find that problematic alcohol use was associated with poverty, social degradation, and injury. Globally, the impact of alcohol use is worse among the poor and marginalized of society (Rehm, 2009, Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders) and alcohol use can also worsen poverty through a loss of finances with excessive spending on alcohol or loss of employment (Amundsen, 2016; Baumberg, 2006). Our participants frequently referred to the “cost” of alcohol in these terms, including both the actual cost of purchasing alcohol, and the opportunity cost of alcohol reducing productive behaviors.

Alcohol Intervention

Although there are limited resources for AUDs, it was commonly believed that there were no treatments available in the Kilimanjaro region. The most cited “treatment option” was counselling from a fellow community member. Participants stated that if other treatment options existed, the community did not know them. This is not surprising given the limited number of mental healthcare professionals and the lack of treatment facilities for alcohol addiction in this region and many LMICs (Perngparn et al., 2008). Alcohol treatment services in LMICs are often integrated with the health system when national-level resources are unavailable, placing the burden on primary care settings (Rathod et al., 2018) and contributing to low treatment coverage (Rathod et al., 2016).

Limitations

The study has certain limitations that warrant discussion. A vast majority of our participants were from one particular tribe (Chagga). Although this provides an accurate representation of the local population, the conclusions reached in this study may not apply to other parts of Tanzania. Similarly, our participants represent a high-risk group for hazardous alcohol use and may overestimate certain alcohol use behaviors among non-injury patients and the community in general. However, previous studies in different regions of Tanzania, have showed similar consumption patterns and attitudes toward drinking (Carlson, 1993; Amemori, 2011; Kilonzo, 2004; Mbatia, 2009). This population was chosen to obtain the perspective of the population for which future selective interventions will be developed and is not intended to represent universal perspectives on social norms surrounding alcohol and its consumption.

Conclusions

This study analyzes injury patient’s perceptions of alcohol use in Moshi, Tanzania. Our analysis found a number of common beliefs regarding alcohol including its cultural and social role, the acceptability of moderate use, variation in stigma, and the lack of treatment resources. These themes can inform future studies to better understand alcohol’s role in health outcomes and to create potential behavioral and policy interventions for this injury population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the KCMC/ Duke Emergency Department Research Team for their hard work and persistence with this and all their projects. Similarly, thanks to Ashley Morgan, Ashley Phillips, and Kaitlyn Friedman for their edits to this manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01TW010000 (PI, Staton). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding agency had no role in study design; or in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts declared.

References

- Adelekan M, Razvodovsky Y, Liyanage U, Ndetei D. 2008. Noncommercial alcohol in three regions. ICAP Review. 2008; 3:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom SK, Osterberg EL. International perspectives on adolescent and young adult drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004; 28: 258. [Google Scholar]

- Amemori M, Mumghamba E, Ruotoistenmäki J, Murtomaa H. Smoking and drinking habits and attitudes to smoking cessation counselling among Tanzanian dental students. Community Dental Health. 2001; 28: 95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen M, Kirkeby T, Giri S, Koju R, Krishna S, Ystgaard B, Solligård E, Risnes K. Non-communicable diseases at a regional hospital in Nepal: Findings of a high burden of alcohol-related disease. Alcohol. 2016; 57: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antai D, Lopez G, Antai J, Anthony D. Alcohol drinking patterns and differences in alcohol-related harm: a population-based study of the United States. BioMed Research International. 2014; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao TT, Sam N, Kiwelu I, Mahal A, Subramanian S, Wyshak G, Kapiga S.Risk factors of alcohol problem drinking among female bar/hotel workers in Moshi, Tanzania: a multi-level analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2011; 15: 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberg B The global economic burden of alcohol: a review and some suggestions. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006; 25: 537–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benegal V, Chand PK, Obot IS. Packages of care for alcohol use disorders in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine. 2009; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blas E, Kurup AS. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes, World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boniface R, Museru L, Kiloloma O, Munthali V. Factors associated with road traffic injuries in Tanzania. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016; 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2005; 4: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TM, Ashley OS. Women in substance abuse treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS), Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RG. Symbolic mediation and commoditization: A critical examination of alcohol use among the Haya of Bukoba, Tanzania. Medical Anthropology. 1993; 15: 41–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chalder M, Elgar FJ, Bennett P. Drinking and motivations to drink among adolescent children of parents with alcohol problems. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2005; 41: 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SP, Pickering RP. Early onset of drinking as a risk factor for lifetime alcohol-related problems. Addiction. 1992; 87: 1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 1990; 13: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou PS, Ruan JW, Grand BF.. Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008; 32: 2149–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galson SW, Staton CA, Karia F, et al. Epidemiology of hypertension in Northern Tanzania: a community-based mixed-methods study BMJ Open 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore W, Chikritzhs T, Stokwell T, Jernigan D, Naimi T, Gilmore I. Alcohol: taking a population perspective. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016; 13: 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse.1997; 9: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006; 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood HJ, Fountain D, Livermore G. Economic costs of alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Springer. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D. Alcohol-specific socialization, parenting behaviors and alcohol use by children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999; 60: 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D, Levine DW. The early use of alcohol and tobacco: its relation to children’s competence and parents’ behavior. American Journal of Public Health.1997; 87: 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis TJ. ARVIS TJ Implications of gender for alcohol treatment research: a quantitative and qualitative review. Addiction. 1992; 87: 1249–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilonzo GP, Hogan NM, Mbwambo JK, Mamuya B, Kilonzo K. Pilot study on patterns of consumption of nonindustrial alcohol beverages in selected sites, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Moonshine Markets: Issues in Unrecorded Alcohol Beverage Production and Consumption, Haworth A and Simpson R (Eds.), Brunner-Routledge, New York, 2004; 10: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus L, Bloomfield K, Augustin R, Reese A. Prevalence of alcohol use and the association between onset of use and alcohol-related problems in a general population sample in Germany. Addiction. 2000; 95: 1389–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Almazroa MA, Amann MA, Anderson HR, Andrews KG. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012; 380: 2224–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet. 2001; 358: 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbatia J, Jenkins R, Singleton N, White B. Prevalence of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking, tobacco and drug use in urban Tanzania, and their associated risk factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009; 6: 1991–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall M Rural brewing, exclusion, and development policy-making. Gender & Development. 1996; 4: 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsunaga T, Larsen U. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with alcohol abuse in Moshi, northern Tanzania. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2008; 40: 379–399. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundenga MM, Sawe HR, Runyon MS, Mwafongo VG, Mfinanga JA, & Murray BL (2019). The prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug use among injured patients presenting to the emergency department of a national hospital in Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC emergency medicine, 19(1), 15. doi: 10.1186/s12873-019-0222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L. Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. The Journal of general psychology. 2006; 133: 357–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, Parry CD, Patra J, Popova S, Poznyak V. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010; 105: 817–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009; 373: 2223–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT. The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2003; 98: 1209–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessman C. Narrative, memory & everyday life. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sa Z, Larsen U. Gender inequality increases women’s risk of HIV infection in Moshi, Tanzania. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2008; 40: 505–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Myers B. Negative attributions towards people with substance use disorders in South Africa: Variation across substances and by gender. BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton CA, Msilanga D, Kiwango G, Vissoci JR, de Andrade L, Lester R, Hocker M, Gerardo CJ, and Mvungi M. A Prospective Registry Evaluating the Epidemiology and Clinical Care of Traumatic Brain Injury Patients Presenting to a Regional Referral Hospital in Moshi, Tanzania: Challenges and the Way Forward. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2015; 24(1): 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton C, Vissoci J, Gong E, Toomey N, Wafula R, Abdelgadir J, Zhou Y, Liu C, Pei F, Zick B. Road traffic injury prevention initiatives: a systematic review and metasummary of effectiveness in low and middle income countries. PLoS One. 2016; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2015. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Table 2.46B—Alcohol Use, Binge Alcohol Use, and Heavy Alcohol Use in Past Month among Persons Aged 12 or Older, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2014 and 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania. Population and housing census: population distribution by administrative areas. Ministry of Finance, Dar es Salaam: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19:349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health, 2014.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.