ABSTRACT

Background

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a neurodegenerative disease without approved therapies, and therapeutics are often tried off‐label in the hope of slowing disease progression. Results from these experiences are seldom shared, which limits evidence‐based knowledge to guide future treatment decisions.

Objectives

To describe an open‐label experience, including safety/tolerability, and longitudinal changes in biomarkers of disease progression in PSP‐Richardson's syndrome (PSP‐RS) patients treated with either salsalate or young plasma and compare to natural history data from previous multicenter studies.

Methods

For 6 months, 10 PSP‐RS patients received daily salsalate 2,250 mg, and 5 patients received monthly infusions of four units of young plasma. Every 3 months, clinical severity was assessed with the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale (PSPRS), and MRI was obtained for volumetric measurement of midbrain. A range of exploratory biomarkers, including cerebrospinal fluid levels of neurofilament light chain, were collected at baseline and 6 months. Interventional data were compared to historical PSP‐RS patients from the davunetide clinical trial and the 4‐Repeat Tauopathy Neuroimaging Initiative.

Results

Salsalate and young plasma were safe and well tolerated. PSPRS change from baseline (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) was similar in salsalate (+5.6 ± 9.6), young plasma (+5.0 ± 7.1), and historical controls (+5.6 ± 7.1), and change in midbrain volume (cm3 ± SD) did not differ between salsalate (–0.07 ± 0.03), young plasma (–0.06 ± 0.03), and historical controls (–0.06 ± 0.04). No differences were observed between groups on any exploratory endpoint.

Conclusions

Neither salsalate nor young plasma had a detectable effect on disease progression in PSP‐RS. Focused open‐label clinical trials incorporating historical clinical, neuropsychological, fluid, and imaging biomarkers provide useful preliminary data about the promise of novel PSP‐directed therapies.

Keywords: progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), salsalate, young plasma, 4RTNI, PSPRS

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a neurodegenerative disease caused by accumulation of 4‐microtubule binding domain repeat tau (4R‐tau) in characteristic cell types and brain regions. PSP accumulation has a well‐defined anatomical pattern of deposition and spread, which leads to reliable clinical syndromes that allow accurate diagnosis and high reproducibility of clinical, neuropsychological, imaging, and fluid biomarkers.1, 2 The classic PSP syndrome, now called PSP‐Richardson's syndrome (PSP‐RS), is defined by progressive oculomotor abnormalities and postural instability, leading to death, on average, 6.9 years after symptom onset. Based on syndrome alone, prevalence of PSP‐RS is estimated to be 2.9 per 100,000.3 Whereas strategies are available to manage PSP symptoms, there are no treatments that reverse, stop, or delay disease progression. Hence, there is great unmet medical need to find effective therapies for PSP, and, out of desperation, many patients pursue off‐label therapies for Parkinson's disease (PD) or other remedies with variable data to provide a rationale for their use.

Currently, a variety of experimental therapeutic approaches to PSP have been proposed, mainly focused on tau protein as a target, but relatively few late‐phase clinical trials have been conducted.1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Large, international clinical trials and multicenter, longitudinal, observation studies have revealed striking consistency in rates of change of clinical rating scales of PSP symptomatology,9 particularly on the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale (PSPRS) and Schwab and England Activity of Daily Living scale (SEADL),10 the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS),11 volumetric MRI measures of midbrain atrophy,12 and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurofilament light chain (NfL) concentrations.13 This suggests that natural history data from earlier longitudinal studies could be used to gauge the potential promise of novel therapeutic interventions, before the initiation of larger, placebo‐controlled trials or in situations where such trials are not practical or possible, including commonly used therapeutics, lifestyle interventions that are widely available, or other desired off‐label interventions by patients and families.

Two initial interventions were chosen to test this approach: salsalate and infusions of plasma from young donors. Salsalate is a commercially available nonsteroidal inflammatory drug (NSAID) used for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and related rheumatological disorders. Salsalate has been proposed as a potential treatment for tauopathies, including PSP, because preclinical data suggest that salsalate inhibits the acetylation of tau, a post‐translational modification of tau that is believed to play a role in toxic gain of function. Levels of acetylated tau are increased in patients with tauopathies,14 and in tau transgenic mice, treatment with salsalate rescued memory deficits and prevented hippocampal atrophy.15 These data provided scientific justification for exploring the effects of salsalate in PSP. A larger, placebo‐controlled trial is also underway for Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients (NCT03277573).

Young plasma (YP) was chosen for the second intervention, given that it has been shown, in a number of aged mouse models, to result in improvements in cognitive function, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis.16, 17 In amyloid transgenic mouse models of AD, plasma‐derived factors improved performance on cognitive tasks.18 In humans, YP is commonly operationalized as fresh frozen plasma obtained from young (aged <30 years) healthy male donors (to reduce the risk of transfusion reactions), with the hypothesis that such plasma contains unknown factor(s) that may ameliorate processes associated with brain aging and cognitive decline. In human AD patients, a small phase 1 trial, PLASMA (Plasma for Alzheimer Symptom Amelioration Study; NCT02256306), found YP to be safe and well tolerated, and whereas no improvement was reported on clinical or neuropsychological outcomes, a possible improvement was noted on functional measures.19 The cost and availability of YP precludes a large‐scale trial in PSP without first obtaining preliminary evidence of safety.

To obtain preliminary data related to the safety and potential for efficacy of these novel interventions, we exposed 5 PSP‐RS patients to 6 monthly infusions of YP and 10 patients to 6 months of daily treatment with oral salsalate. The primary endpoints were safety and tolerability. We screened for large treatment effects on PSP symptoms using a threshold value of a 40% difference in mean change from baseline on the PSPRS in YP‐ or salsalate‐treated patients compared to historical controls.20 To screen for other potential effects of salsalate or YP treatment in PSP‐RS, we also measured the 6‐month change on several exploratory clinical, neuropsychological, imaging, and fluid biomarkers (see Outcomes below).

Methods

Trial Oversight and Design

The salsalate trial recruited from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF; San Francisco, CA) Memory and Aging Center and the Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, OR) Parkinson Center & Movement Disorder Program between June 2015 (first person screened) to February 2018 (last person completed). YP patients were recruited from UCSF, and the trial ran from June 2015 to August 2017. Institutional review board approval was obtained at both sites, and trials were registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (salsalate, NCT02422485; YP, NCT02460731). Written informed consent was obtained from patients and caregivers. All patients met 2017 International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society criteria for PSP‐RS2; were aged 50 to 85 years; had a Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) 14‐30 (inclusive); MRI consistent with PSP; and were on stable medications at least 1 month before screening, except for U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved AD and PD medications, which were stable for at least 2 months before screening. Patients were excluded who met 2011 National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer's Association criteria for probable AD21; demonstrated a sustained response to levodopa; or had any other medical condition that accounted for symptoms. For salsalate, additional exclusion criteria included history of severe hypertension, gastrointestinal bleed or ulcers, aspirin triad or asthma; or concurrent use of thiazides, loop diuretics, corticosteroids, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, or other NSAIDs (except daily aspirin). For YP, additional exclusion criteria included history of transfusion complications; intolerance to intravenous fluids; immunoglobulin A deficiency; uremia or bleeding; or concurrent use of anticoagulants.

Study Procedures and Outcomes

After screening, each patient had a baseline visit where study drug was initiated, followed by 6 monthly visits, including a final visit 2 weeks after the last dose. Salsalate patients were given 2,250 mg daily in divided doses for 6 months. This regimen was comparable to preclinical data and the usual dosage regimens for rheumatic disorders (3,000 mg daily). YP was administered at a transfusion facility in a manner consistent with similar trials.19 Healthy male donor plasma (aged <30 years) was used to minimize risk of transfusion reactions, and four units were intravenously infused once‐monthly for 6 months. After peripheral access was obtained, transfusions began at a rate of 2 mL/min for 15 minutes, and then flow rate was increased up to a maximum rate of 300 mL/h, depending on subject tolerance, size, cardiac status, and hemodynamic condition. Vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, temperature, and O2 saturation) were taken within 1 hour before the start of infusion, 15 minutes (±5) after the start of the infusion, and at the end of the infusion to monitor for transfusion reactions. Premedications were not routinely given, but if subjects experienced mild transfusion reactions (pruritus, urticarial, flushing, or febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions), diphenhydramine 25 mg IV or acetaminophen 325 mg PO were given 30 minutes before each future transfusion at the discretion of the investigator.

The primary outcome was safety and tolerability. Adverse events (AEs) were grouped by MedRA system organ class (http://www.meddra.org), and investigators recorded whether AEs were thought related to study drug. Serious AEs were defined as those leading to hospitalization or death. The prespecified secondary outcome was reduction in progression of PSPRS by 40% compared to historical controls, a composite outcome of clinically meaningful disease progression used in earlier PSP‐RS trials.5, 9 Additional measures collected included SEADL,22 Clinical Global Impression–Severity Scale (CGI‐S), Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes (CDR‐SB),23 RBANS,24 and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).25

Structural MRIs were acquired on a 3‐Tesla (T) Siemens Tim Trio or a 3T Siemens Prisma‐Fit scanner (Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany). Before preprocessing, images were visually inspected for quality control. Tissue segmentation was performed using SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, London, UK; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) unified segmentation.26 Each native space image was warped to create a study‐specific template using Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration using Exponentiated Lie algebra (DARTEL).27 In the study‐specific template, gray and white matter tissues were modulated and smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with 4‐mm full width at half maximum. For statistical purposes, linear and nonlinear transformations between DARTEL's space and International Consortium of Brain Mapping space were applied.28 Regions of interest were extracted from the Desikan‐Killiany‐Tourville atlas.29

At least 20 mL of CSF was collected by lumbar puncture into sterile polypropylene tubes, using a previously described protocol.30 Within 30 minutes, CSF samples were centrifuged at 2,000g at room temperature for 5 minutes, aliquoted into 500‐μL cryovials and stored at −80°C. Plasma NfL concentrations were measured using a commercially available NfL kit on the Simoa HD‐1 platform (Quanterix, Lexington, MA), where samples were 4× diluted and automated by the HD‐1 analyzer. Levels of amyloid beta (Aβ), total tau, and tau phosphorylated at 181 (pTau181) were measured using the Elecsys CSF assays run on the cobas e601 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), as previously described.31 All biomarkers were measured in duplicate (twice concurrently) to ensure coefficients of variance <25%, and the average concentration was used for analyses.

Comparison Cohort

All collected biomarkers were compared to available natural history data from historical PSP‐RS patients seen through a previous clinical trial of davunetide (NCT01110720; n = 305)9 and the longitudinal natural history observational cohort, 4RTNI (4‐Repeat Tauopathy Neuroimaging Initiative; NCT01804452; n = 43). As available, demographics, clinical measures, neuropsychological assessments, MRI, and fluid biomarkers were aggregated for each historical control at baseline, and 6‐month change was calculated for comparison to treatment trial length. Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria are available at each reference, but baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were comparable to interventional groups.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in baseline and interval biomarker values were assessed with Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal‐Wallis’ test for continuous variables after assessment of normality of distribution. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A linear mixed‐effect model evaluated the relationship of PSPRS and midbrain atrophy over time. The model allowed random intercepts at subject level and were adjusted for age and sex. For correlations, pair‐wise Pearson's r was calculated, and significance was corrected by Bonferroni for multiple comparisons. All biomarkers were normally distributed, except NfL concentration, which was log‐transformed. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (Stata 14.0; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and R software (version 3.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austra).

Results

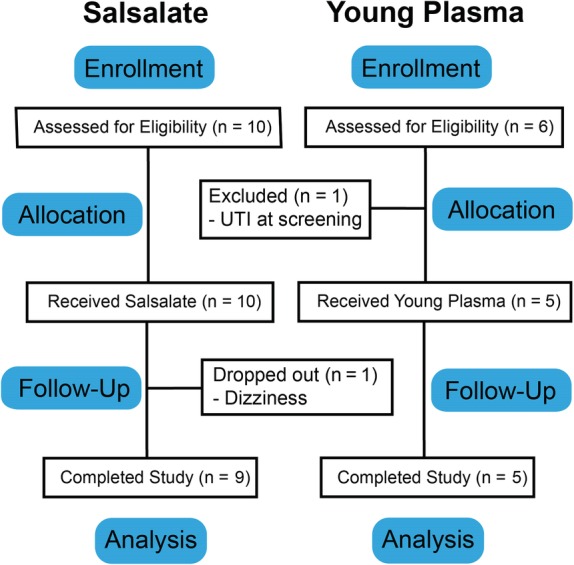

For salsalate, 10 patients were screened for eligibility and enrolled (Fig. 1). One patient dropped out because of dizziness and did not participate in an early termination visit. AEs from this patient were included in the safety profile, but because of the lack of endpoint data, this patient was not included in longitudinal biomarker analyses. For YP, 6 patients were screened for eligibility, and 1 patient was excluded at screening because of a urinary tract infection (UTI), and thus 5 patients were enrolled, completed the study, and were included in safety profiling and analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Only one serious AE was noted in either trial, when a salsalate patient developed a pulmonary embolism (PE) attributed to a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which was deemed unrelated to the study drug and potentially related to a recent long flight. This patient completed the trial and was included in analyses. Overall, the number of nonserious AEs in both trials was similar to the placebo control group from davunetide (Table 1). The most common AE in all cohorts was falls, which was expected given that part of the diagnostic criteria for PSP‐RS is postural instability. For salsalate, only two mild AEs were attributed to the study drug: one report of easier bruising and one upset stomach. For YP, 1 patient developed itching and a mild rash during infusion, thought to be a mild infusion reaction, and another two AEs of soft‐tissue swelling were thought to be possibly related to the infusion.

Table 1.

Safety/tolerability of salsalate and young plasma compared to historical placebo cohort

| Historical Placebo, N (% cohort) | Salsalate, N (% cohort) | YP, N (% cohort) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least one event | 148 (94.9) | 9 (90) | 5 (100) |

| All AEs by system organ class | |||

| Cardiovascular (palpitations, QRS complex widening) | 10 (6.4) | 1 (10 | 1 (20) |

| Dermatologic (flushing, itching, rash) | 21 (13.5) | 1 (10) | 5 (40) |

| Eye/vision (irritation, worsening vision) | 20 (12.8) | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal (constipation, dyspepsia) | 48 (30.8) | 3 (30) | 0 |

| Infections (skin infection, UTI) | 68 (43.6) | 1 (10) | 1 (20) |

| Injuries (falls, lacerations, contusions) | 86 (55) | 11 (50) | 10 (60) |

| Musculoskeletal (fracture, joint/muscle pain) | 43 (27.6) | 12 (60) | 3 (40) |

| Nervous system (dizziness, fatigue, headache) | 62 (39.7) | 2 (20) | 4 (60) |

| Respiratory (cough, congestion, shortness of breath, PE) | 61 (39.1) | 5 (30) | 1 (20) |

| Serious AEs | 54 | 1 (DVT/PE) | 0 |

At baseline, the trial groups and historical controls were not different on demographic measures, clinical severity, neuropsychological testing, or regional brain volume measured on structural MRI (Table 2). Disease severity was assessed with the PSPRS, a composite symptom scale ranging from 0 (unaffected) to 100, and was not different in historical controls compared to the salsalate cohort and YP cohort. No baseline differences were found between groups on other clinical measures of severity, including SEADL, CGI‐S, and CDR‐SB. Baseline cognitive impairment was assessed with the RBANS, a brief tool validated in patients with PSP‐RS with a normative index score of 100 (SD, 15),11 and scores were comparable at baseline. Additionally, no differences were noted on MMSE or GDS, a measure of depressive symptoms. Baseline midbrain volume on MRI was similar in each group, and no differences were noted in degree of atrophy in other brain regions, including pons or superior cerebellar peduncle (SCP).

Table 2.

Baseline clinical characteristics and change over 6 months

| Historical Controls | Salsalate | YP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, baseline | (n = 355) | (n = 9) | (n = 5) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 68.1 (6.9) | 67.6 (3.1) | 71.8 (3.6) | 0.46a |

| Male, n (%) | 186 (52.4) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (40.0) | 0.76b |

| White, n (%) | 301 (86.4) | 7 (77.8) | 5 (100) | 0.05b |

| Education, mean (SD) | 15.7 (4.1) | — | 16.3 (3.5) | 0.80a |

| Clinical severity, baseline | (n = 313) | (n = 9) | (n = 5) | |

| PSPRS, mean (SD) | 39.2 (11.5) | 37.8 (13.7) | 35.8 (19.1) | 0.77a |

| SEADL, mean % (SD) | 53.2 (22.5) | 58.9 (21.8) | 50 (28.3) | 0.72a |

| CGI‐S, mean (SD) | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (1.1) | 0.83a |

| CDR‐SB, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.9) | 3.8 (2.1) | 4.8 (4.7) | 0.98c |

| Neuropsychological testing, baseline | (n = 318) | (n = 9) | (n = 5) | |

| RBANS, mean (SD) | 73.1 (13.1) | 79.2 (9.7) | 78.2 (19.8) | 0.27a |

| GDS, mean (SD) | 12.7 (6.8) | 9.3 (6.9) | 8.2 (6.2) | 0.09c |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 26.3 (3.5) | 26.8 (2.8) | 26.8 (4.0) | 0.91c |

| MRI volume, baseline | (n = 226) | (n = 8) | (n = 5) | |

| Midbrain, mean cm3 (SD) | 4.77 (0.62) | 4.91 (0.80) | 4.47 (0.71) | 0.46a |

| Pons, mean cm3 (SD) | 10.88 (1.56) | 11.45 (1.30) | 10.42 (1.78) | 0.47a |

| SCP, mean cm3 (SD) | 0.26 (0.03) | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.25 (0.05) | 0.81a |

| Clinical severity, change | (n = 306) | (n = 9) | (n = 5) | |

| PSPRS, mean change (SD) | +5.6 (7.1) | +5.6 (9.6) | +5.0 (7.1) | 0.98a |

| SEADL, mean change (SD) | –9.2 (14.0) | –15.6 (20.1) | –6.0 (19.5) | 0.37a |

| CGI‐C, mean score (SD) | 4.8 (0.9) | 5.3 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.4) | 0.16a |

| Neuropsychological testing, change | (n = 246) | (n = 8) | (n = 5) | |

| RBANS, mean change (SD) | –6.2 (6.9) | –6.9 (7.6) | –2.4 (10.0) | 0.46a |

| GDS, mean change (SD) | +0.6 (4.9) | +0.8 (5.2) | +2.2 (4.8) | 0.76a |

| MRI volume, change | (n = 226) | (n = 8) | (n = 5) | |

| Midbrain, mean change cm3 (SD) | –0.06 (0.04) | –0.07 (0.03) | –0.06 (0.03) | 0.69a |

| Pons, mean change cm3 (SD) | –0.13 (0.10) | –0.19 (0.13) | –0.12 (0.10) | 0.29a |

| SCP, mean change cm3 (SD) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | N/A |

| CSF biomarkers, change | (n = 24) | (n = 8) | (n = 5) | |

| NfL, % change baseline (SD) | +28.6% (86.9) | +44.0% (72.2) | +22.9% (62.6) | 0.96c |

| Aβ, % change baseline (SD) | +4.1% (17.9) | –17.1% (17.5) | –13.8% (27.8) | 0.06c |

| Total tau, % change baseline (SD) | +6.5% (23.3) | –6.2% (5.4) | –0.4% (4.4) | 0.13c |

| pTau181, % change baseline (SD) | –2.8% (12.2) | –3.7% (9.6) | +0.4% (5.7) | 0.58c |

One‐way ANOVA.

Fisher's exact test.

Kruskal‐Wallis' test by ranks.

N/A, not applicable.

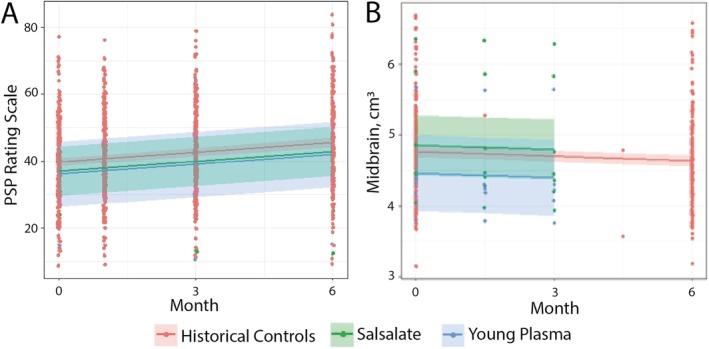

After 6 months of treatment, no effect was observed on the prespecified secondary outcome of change on the PSPRS in either treatment group compared to historical controls (Fig. 2A). Mean change in PSPRS after 6 months of treatment with salsalate was an increase of 5.6, identical to changes in PSPRS in historical controls, a pace of progression consistent with earlier reported studies (Table 2).20 YP showed a small absolute reduction, with a change of 5.0 (SD, 7.1) compared to 5.6 (SD, 7.1) in historical controls, but this degree of change (–10.7%) was below the prespecified 40% reduction threshold prespecified as indicative of further consideration. Exploratory clinical and neuropsychological outcomes tested at month 6 included the SEADL, Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI‐C), RBANS, and GDS, but no difference was noted between either trial group from historical controls on these measures (Table 2). The CDR‐SB and MMSE were not collected at month 6.

Figure 2.

Progression on PSPRS and rate of midbrain atrophy did not differ between trial groups and historical controls. Lines represent linear mixed‐effect regression over time in each cohort, with the shaded area representing 95% confidence intervals around the calculated mean. Trial data (salsalate and YP) are compared to available historical control data. At baseline, PSPRS and midbrain volume were not different between trial cohorts or historical controls, and no difference was found in (A) progression on PSPRS or (B) atrophy of midbrain between the three groups, though the large confidence intervals attributable to small sample size should be noted.

Volumetric MRI changes in midbrain, pons, and SCP were chosen for analysis based on earlier studies showing that these regions require the smallest sample size to detect a therapeutic effect in PSP‐RS.12 However, in parallel with clinical and neuropsychological testing, no difference was noted in rate of midbrain atrophy after 6 months of treatment with either salsalate or YP when compared to data available from historical controls (collected over 12 months; Fig. 2B). Furthermore, no differences were noted in rate of pontine or SCP atrophy, and SCP did not atrophy appreciably over the six months of the study (Table 2).

CSF NfL concentration was examined based on previous analyses showing its utility as a biomarker in PSP‐RS attributable to correlation with both clinical severity and imaging changes,1 and Aβ, total tau, and pTau181 were included given that they are commonly used fluid biomarkers of AD pathology.32 Baseline CSF concentrations of fluid biomarkers were not directly comparable given known batch‐to‐batch variability. Therefore, percent change from baseline was used for comparison, and similar to other biomarkers, no effect was observed on NfL concentration in the trial groups compared to historical controls, and increasing concentration was noted in all cohorts (Table 2). Aβ, total tau, and pTau181 concentrations had higher variability, but rate of change was not significantly different between groups.

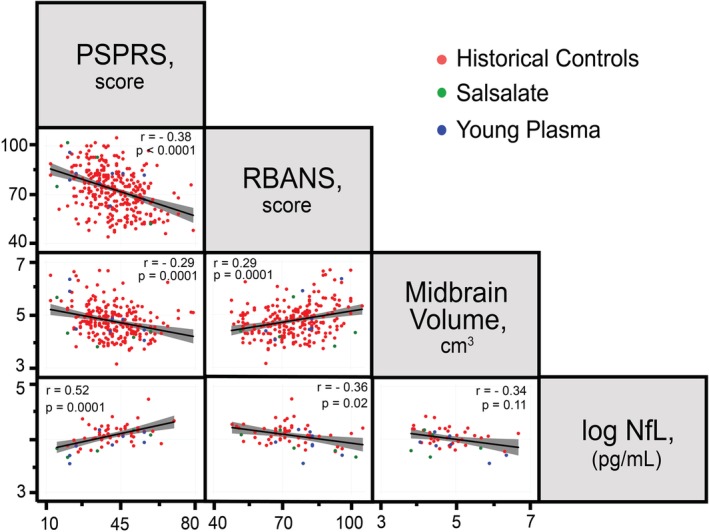

To assess the relationship between individual independent biomarkers, a correlation analyses was conducted on a selected measure of clinical severity (PSPRS), cognitive impairment (RBANS), volumetric atrophy (midbrain), and fluid biomarker (CSF NfL). Data represent baseline assessments and are normally distributed, with the exception of NfL concentration, which was log‐transformed. Moderately strong and significant correlations were found between the PSPRS, RBANS, midbrain volume, and NfL, with the exception of midbrain volume and NfL, which did not reach significance (Fig. 3). Specifically, disease severity on the PSPRS was correlated with worsened cognitive impairment on the RBANS, decreased midbrain volume, and increased CSF NfL, suggesting that these biomarkers are consistently interrelated in patients with PSP‐RS.

Figure 3.

PSPRS, RBANS, midbrain volume, and NfL are highly correlated in PSP‐RS. Data represent pair‐wise scatterplots of biomarkers at baseline examination with linear best‐fit line and confidence interval. Pearson's correlation (r) was calculated for each biomarker pair and displayed with significance of correlation, after Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons (p).

Discussion

Two pilot open‐label phase 1 futility studies were conducted, evaluating salsalate (NCT02422485) and YP (NCT02460731) in 10 and 5 patients with PSP‐RS, respectively, and whereas the interventions were found to be safe and well tolerated, no effect was observed on disease progression as measured by the PSPRS, and no differences were found on a range of exploratory biomarkers when these cohorts were compared to historical controls from the interventional trial with davunetide (NCT01110720)9 and the observational study, 4RTNI (NCT01804452).12 At baseline, trial participants and historical controls were well matched given that they were both demographically comparable and statistically similar on diverse biomarkers, including clinical assessments, neuropsychological testing, and imaging volumetrics. Patients were mildly to moderately affected, as measured by disease severity on the PSPRS, similar to other trials conducted in this cohort.5, 9

These two studies provide limited evidence that salsalate and YP are safe and well tolerated in this population, given that only one serious AE was noted (DVT/PE in the salsalate trial), and it was deemed unrelated to treatment. In terms of efficacy, no difference was found on progression as measured by the PSPRS, the prespecified secondary outcome, after 6 months of treatment with either salsalate or YP. The small absolute difference in progression observed in YP was not considered to be clinically meaningful and did not meet the prespecified threshold for futility. Further exploratory analyses did not show a large or significant pharmacodynamic effect of either salsalate or YP infusions on clinical measures (SEADL, CGI‐C), neuropsychological testing (RBANS, GDS), volumetric imaging (midbrain, pons), or CSF biomarkers (NfL, Aβ, total tau, and pTau181). A strong inter‐relation was found between several highly reproducible biomarkers (PSPRS, RBANS, midbrain atrophy, and NfL in CSF), supporting their use in future clinical trials in this population.

Overall, using an open‐label approach with comparison to historical controls, we have used rigorous methods to evaluate the promise of two therapeutics that are currently used off‐label and found no evidence they are beneficial in a well‐characterized cohort of PSP‐RS patients. It is possible that other neurodegenerative diseases may yet show benefit of salsalate and YP, and given the recent report of key differences in clinical trajectories and biomarker profiles between non‐Richardson's subtypes of PSP and corticobasal syndrome, use in other 4R‐tau variants is also not precluded.33 There are a number of important limitations to this approach, including its small sample size and lack of statistical power, and it should be noted that these trials were designed for initial analysis of safety and tolerability and only powered to detect very large differences in efficacy; therefore, statistical comparison should be de‐emphasized in favor of a qualitative analysis. Furthermore, the lack of randomization and comparison to a large, untreated, historical clinical cohort allows for overestimation of efficacy by contamination of the placebo effect.

Nevertheless, in a disease such as PSP, where no current treatment options exist, patients and treating physicians often have a strong desire to try off‐label therapies, and these data, though preliminary, are highly valuable for patients and their families as well as treating physicians. This pilot futility approach may also be useful in screening therapeutics when larger or longer clinical trials are not available, an increasingly likely scenario after recent announcements of negative studies for antitau antibodies ABBV 8E12 and gosuranemab, leaving only a single active clinical trial testing a disease‐modifying therapy in PSP‐RS (UCB0107, NCT04185415).

Furthermore, the incorporation of highly correlated and reproducible biomarkers as exploratory outcomes allows for better characterization of disease progression and refinement of trial design, which could be iterated, especially given that the current design allows trial completion in only 6 months. In the future, improved models of disease progression, which incorporate biomarkers identified from observational and interventional trials, may improve statistical comparison between groups and allow smaller, even personalized, clinical trials. Our current approach, however, combines safety profiling with individual comparison of standardized progression biomarkers, providing a model for early‐phase drug investigation in rare diseases where multiple large phase 2/3 clinical trials are not feasible.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

L.V.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B

M.L.D.: 1B, 1C, 3B

S.F., M.F., E.H., H.W.H., K.K., N.O., J.R., C.W.: 1C, 3B

P.A.L., J.C.R.: 1B, 1C, 3B

D.M., E.G.T., A.W.: 2B, 2C, 3B

P.W.: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

M.K., J.F.Q., R.T.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

A.L.B.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines. Institutional review board approval was obtained at both USCF and OHSU sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their caregivers.

Financial Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The study was funded by the Tau Consortium and by NIH grant 2R01AG038791. J.C.R. received funds from the NIH and is a site investigator for clinical programs sponsored by Eli‐Lilly. J.F.Q. is reimbursed for DSMB service by VTV Pharmaceuticals and Retrophin. R.T. received research funds from the NIH; has served as a consultant for Grifols, ExpertConnect, and Barclays; and is currently an employee of Denali Therapeutics. A.L.B. received research support from the NIH, the Tau Research Consortium, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia, Corticobasal Degeneration Solutions, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, and the Alzheimer's Association. He has served as a consultant for Aeton, AbbVie, Alector, Amgen, Arkuda, Arvinas, Asceneuron, Ionis, Lundbeck, Novartis, Passage BIO, Samumed, Third Rock, Toyama, and UCB and received research support from Avid, Biogen, BMS, C2N, Cortice, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and TauRx.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: L.V. has received travel support from the Tau Consortium and salary support through a 5T32AG023481 grant. M.L.D. receives medical loan repayment support through the NIH‐NINDS Loan Repayment Program. J.C.R. received funds from the NIH (K23AG059888) and is a site investigator for clinical programs sponsored by Eli‐Lilly. J.F.Q. is reimbursed for DSMB service by VTV Pharmaceuticals and Retrophin. R.T. has received research support from the NIH (K23AG055688) and University of California; has served as a consultant for Grifols, ExpertConnect, and Barclays; and currently works as Associate Medical Director at Denali Therapeutics. A.L.B. receives research support from the NIH, the Tau Research Consortium, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia, Corticobasal Degeneration Solutions, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, and the Alzheimer's Association. He has served as a consultant for Aeton, AbbVie, Alector, Amgen, Arkuda, Arvinas, Asceneuron, Ionis, Lundbeck, Novartis, Passage BIO, Samumed, Third Rock, Toyama, and UCB and received research support from Avid, Biogen, BMS, C2N, Cortice, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and TauRx.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Boxer AL, Yu JT, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Lang AE, Hoglinger GU. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: new diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:552–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, et al, Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: the Movement Disorder Society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32:853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coyle‐Gilchrist IT, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology 2016;86:1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shoeibi A, Litvan I. Therapeutic options for progressive supranuclear palsy including investigational drugs. Exp Opin Orphan Drugs 2017;5:575–587. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Apetauerova D, Scala SA, Hamill RW, et al. CoQ10 in progressive supranuclear palsy: A randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016;3:e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boxer AL, Qureshi I, Ahlijanian M, et al. Safety of the tau‐directed monoclonal antibody BIIB092 in progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomised, placebo‐controlled, multiple ascending dose phase 1b trial. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsai RM, Miller Z, Koestler M, et al. Reactions to multiple ascending doses of the microtubule stabilizer TPI‐287 in patients with Alzheimer disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2019. Nov 11. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3812. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tolosa E, Litvan I, Hoglinger GU, et al. A phase 2 trial of the GSK‐3 inhibitor tideglusib in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2014;29:470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boxer AL, Lang AE, Grossman M, et al. Davunetide in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:676–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bang J, Lobach IV, Lang AE, et al. Predicting disease progression in progressive supranuclear palsy in multicenter clinical trials. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;28:41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duff K, McDermott D, Luong D, Randolph C, Boxer AL. Cognitive deficits in progressive supranuclear palsy on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2019;41:469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dutt S, Binney RJ, Heuer HW, et al. Progression of brain atrophy in PSP and CBS over 6 months and 1 year. Neurology 2016;87:2016–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rojas JC, Bang J, Lobach IV, et al. CSF neurofilament light chain and phosphorylated tau 181 predict disease progression in PSP. Neurology 2018;90:e273–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Min SW, Cho SH, Zhou Y, et al. Acetylation of tau inhibits its degradation and contributes to tauopathy. Neuron 2010;67:953–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Min SW, Chen X, Tracy TE, et al. Critical role of acetylation in tau‐mediated neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits. Nat Med 2015;21:1154–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katsimpardi L, Litterman NK, Schein PA, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science 2014;344:630–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Villeda SA, Plambeck KE, Middeldorp J, et al. Young blood reverses age‐related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat Med 2014;20:659–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Middeldorp J, Lehallier B, Villeda SA, et al. Preclinical assessment of young blood plasma for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:1325–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sha, S.J. , Deutsch G.K., Tian L., et al., Safety, tolerability, and feasibility of young plasma infusion in the plasma for Alzheimer symptom amelioration study: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Golbe LI, Ohman‐Strickland PA. A clinical rating scale for progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 2007;130(Pt. 6):1552–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwab RS. Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson's disease In: Billingham FH, Donaldson MC, (eds.). Third Symposium on Parkinson's Disease. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1969:152–157. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1998;20:310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982;17:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 2005;26:839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 2007;38:95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fonov, V.S. , Evans A.C., McKinstry R.C., Almli C., and Collins D., Unbiased nonlinear average age‐appropriate brain templates from birth to adulthood. NeuroImage 2009;47(Suppl. 1):S102. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klein A, Tourville J. 101 labeled brain images and a consistent human cortical labeling protocol. Front Neurosci 2012;6:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ljubenkov PA, Staffaroni AM, Rojas JC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers predict frontotemporal dementia trajectory. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1250–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Willemse EAJ, van Maurik IS, Tijms BM, et al. Diagnostic performance of Elecsys immunoassays for cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in a nonacademic, multicenter memory clinic cohort: the ABIDE project. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2018;10:563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jack CR, Jr. , Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA‐AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jabbari, E. , Holland N., Chelban V., et al., Diagnosis across the spectrum of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2019. Dec 20. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4347. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]