Abstract

Knee degeneration involves all the major tissues in the joint. However, conventional MRI sequences can only detect signals from long T2 tissues such as the superficial cartilage, with little signal from the deep cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons, and bone. It is highly desirable to develop new sequences which can detect signal from all major tissues in the knee.

We aimed to develop a comprehensive quantitative three dimensional Ultrashort Echo Time (3D UTE) Cones imaging protocol for a truly “whole joint” evaluation of knee degeneration. The protocol included 3D UTE-Cones actual flip angle imaging (3D UTE-Cones-AFI) for T1 mapping, multi-echo UTE-Cones with fat suppression for T2* mapping, UTE-Cones with adiabatic T1ρ (AdiabT1ρ) preparation for AdiabT1ρ mapping, and UTE-Cones magnetization transfer (UTE-Cones-MT) for MT ratio (MTR) and modeling of macromolecular proton fraction (f). An elastix registration technique was used to compensate for motion during scans. Quantitative data analyses were performed on the registered data. Three knee specimens and 15 volunteers were evaluated at 3T.

The elastix motion correction algorithm worked well in correcting motion artifacts associated with relatively long scan times. Much improved curve fitting was achieved for all UTE-Cones biomarkers with greatly reduced root mean square errors (RMSE). The averaged T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and f for knee joint tissues of 15 healthy volunteers were reported.

The 3D UTE-Cones quantitative imaging techniques (i.e. T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and MT modeling) together with elastix motion correction provide robust volumetric measurement of relaxation times, MTR, and f of both short and long T2 tissues in the knee joint.

Keywords: ultrashort echo time, T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MT, motion correction, knee, quantitative analyses

Introduction

It is well understood that knee joint degeneration involves all the major tissues or tissue components, including both the superficial and deep layers of articular cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons, and bone (1–4). However, conventional clinical MRI sequences can only detect signals from long T2 tissues such as the superficial layers of articular cartilage, with little or no signal detected from the deep layers of articular cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons, and bone (5). It is highly desirable to develop new sequences such as ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequences to detect signal from all the major tissue components in the knee joint for a truly “whole joint” evaluation of knee degeneration.

Quantitative MRI is preferable for evaluation of early joint degeneration since morphological changes are typically associated with late stage degeneration (6). Most researchers have focused on T2 and continuous wave T1ρ (CW-T1ρ) measurements of the superficial layers of articular cartilage (7–9). Recently, we developed UTE with variable flip angles (VFA) for T1 measurement (10), UTE with clusters of adiabatic full passage (AFP) pulses for reliable measurement of adiabatic T1ρ (AdiabT1ρ) (11), and UTE with magnetization transfer (UTE-MT) imaging and signal modeling for quantitative assessment of water and macromolecular proton fractions (f) and exchange rates (12). Additionally, we developed the UTE actual flip angle (UTE-AFI) sequence for volumetric B1 mapping for correction of quantitative T1, AdiabT1ρ, and MT modeling of both short and long T2 tissues (10, 13). Moreover, UTE acquisitions with variable TE delays were used to map T2* of all tissues in the knee joint (14). Those UTE sequences can be combined into a single protocol for comprehensive quantitative evaluation of various knee joint tissues in vivo. Specially, previous studies have reported that T1, AdiabT1ρ, and f are much less sensitive to the magic angle effect than T2, which is extremely important for the study of collagen-rich tissues (15–17). Thus, this comprehensive quantitative UTE technique can likely help to evaluate knee joint degeneration more robustly than conventional clinical sequences.

However, quantitative imaging typically involves multiple acquisitions, leading to much longer scan time over morphological imaging. The above quantitative UTE sequences involve UTE-AFI, UTE-VFA, UTE-AdiabT1ρ, UTE-T2*, and UTE-MT imaging, and are therefore time-consuming. The long acquisition process may lead to substantial subject motion, causing potential errors in quantitative measurements. One approach to resolve this challenge is to perform image registration to minimize motion artifacts before any quantitative data analysis.

In this study, we aimed to develop a comprehensive quantitative UTE-Cones imaging protocol for evaluation of various knee joint tissues in vivo with motion correction. Specifically, UTE-Cones-AFI, UTE-Cones-VFA, multi-echo UTE-Cones with fat suppression, UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ, and UTE-Cones-MT data were acquired for each knee joint. This is the first study to apply UTE-Cones-MT modeling in the study of whole knee joint tissues, including articular cartilage, menisci, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), tendon, and muscle. The elastix registration toolbox, a registration library developed by Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit (ITK) to address medical image registration problems, was used to compensate for inter-scan motion (18, 19). Quantitative data analyses were then performed on the registered data. To evaluate the robustness of the new approach, three knee joint specimens with and without manually introduced motion were scanned with the same protocol, and the measured values were compared. Then, the protocol was applied to 15 healthy volunteers to evaluate the robustness of the proposed techniques in quantitative imaging of knee joint tissues in vivo at 3T.

Method

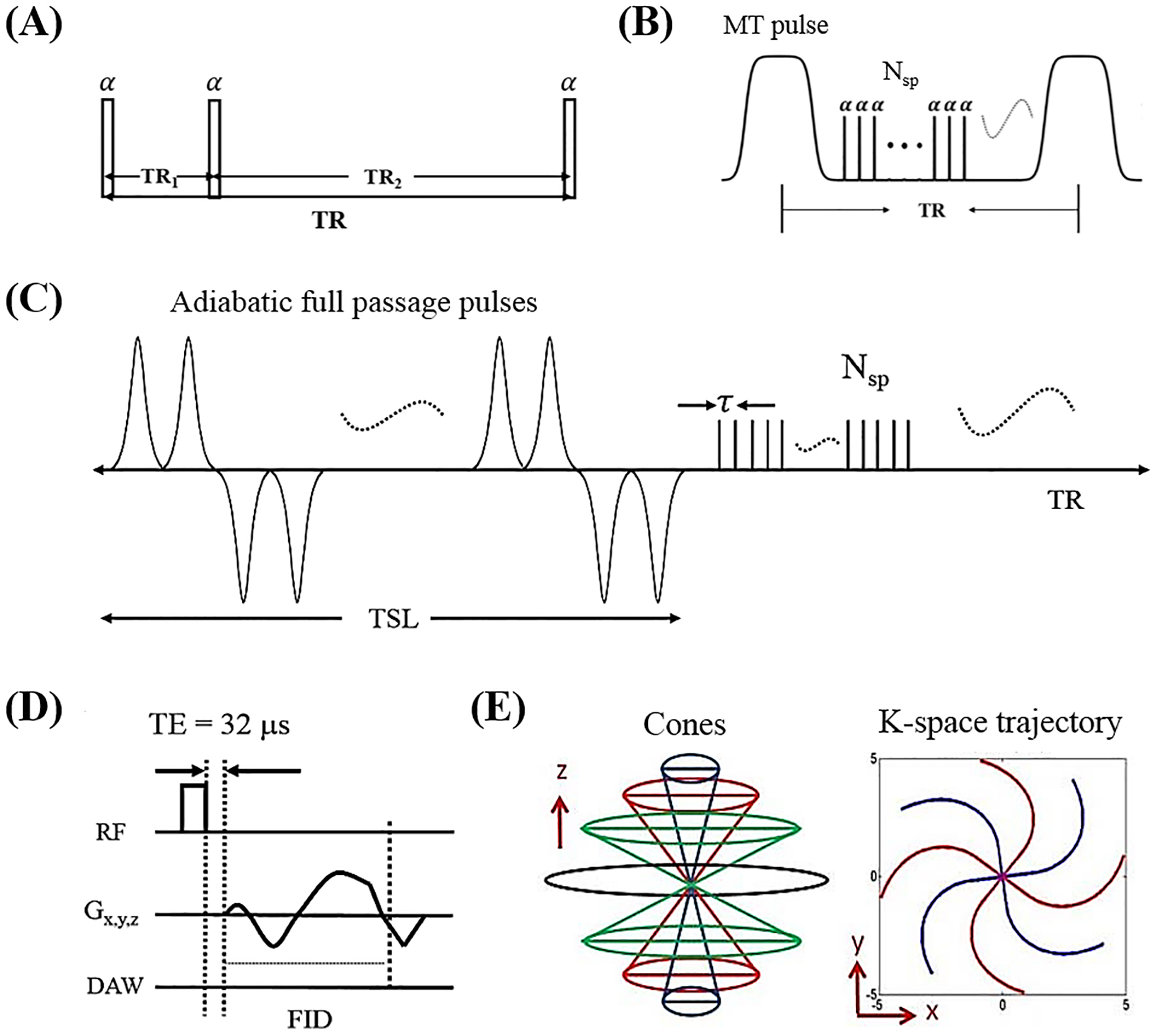

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with guidelines of the institutional review board (IRB). The 3D UTE-Cones sequences were implemented on a 3T MR750 scanner (GE Healthcare Technologies, Milwaukee, WI) (Figure 1) (20). An 8-channel knee coil that is a transmit/receive coil was used for signal excitation and reception. To compensate for B1 inhomogeneity regarding quantitative T1, AdiabT1ρ, and MT modeling, we implemented a UTE-Cones-AFI scheme for volumetric B1 mapping, where two UTE datasets were acquired with different TRs (Figure 1A) (10, 13). 3D UTE-Cones-VFA data acquisitions were used for T1 measurement (10). MTR and MT modeling were performed based on UTE-Cones-MT data acquired with a series of MT powers and frequency offsets (Figure 1B). The details on two-pool MT modeling were reported in prior publications (12, 21–23). 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ was used for volumetric T1ρ assessment of both short and long T2 tissues in the knee joint, where identical non-selective AFP pulses with a duration of 6.048 ms, bandwidth of 1.643 kHz, and maximum B1 amplitude of 17 μT were used to generate T1ρ contrast (Figure 1C) (11). Multispoke acquisition after each MT or AdiabT1ρ preparation was incorporated for improved time-efficiency (e.g., Nsp spokes were acquired per MT or adiabatic T1ρ preparation). T2* was quantified by acquiring multi-echo UTE-Cones data with chemical shift-based fat suppression (24). The basic 3D UTE-Cones sequence employed a short rectangular pulse for signal excitation (Figure 1D), followed by k-space data acquisition along twisted spiral trajectories ordered in the form of multiple cones (Figure 1E) (20).

Figure 1.

The quantitative 3D UTE-Cones sequences. (A) is the UTE-Cones-AFI sequence with dual-TR acquisitions for B1 mapping. (B) and (C) are the MT- and AdiabT1ρ-prepared UTE-Cones sequences for MTR/MT modeling and T1ρ measurement, respectively. To speed up data acquisition, multiple spokes (Nsp) were sampled after both MT and adiabatic T1ρ preparation. In the basic 3D UTE-Cones sequence (D), a short rectangular pulse was used for signal excitation followed by 3D spiral sampling with a minimal nominal TE of 32 μs. The spiral trajectories were arranged with conical view ordering (E).

The quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging protocol was applied to three cadaveric human knee specimens (aged 31–54 years, mean age 43.3 ± 11.6 years; 2 males, 1 female) and 15 healthy volunteers (aged 20–49 years, mean age 33.2 ± 8.9 years; 6 males, 9 females). The 3D UTE-Cones sequences used to scan these knee joints employed the same field of view (FOV) of 15×15×10.8 cm3 and receiver bandwidth of 166 kHz. Other sequence parameters were: 1) 3D UTE-Cones-AFI: TR1/TR2 = 20/100 ms, flip angle = 45°, matrix = 128×128×18 and a total scan time = 4 min 57 sec; 2) 3D UTE-Cones-VFA: TR = 20 ms; flip angle = 5°, 10°, 20°, and 30°; matrix = 256×256×36; and total scan time = 9 min 28 sec; 3) 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ: TR = 500 ms; FA = 10°; matrix = 256×256×36; Nsp = 25, spin-locking time (TSL) = 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, and 96 ms; number of AFP pulses NAFP = 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 16; each with a scan time of 2 min 34 sec; 4) 3D UTE-Cones-T2*: TR = 45 ms; FA = 10°; matrix = 256×256×36; fat saturation; multi-echo of 0.032, 4.4, 8.8, 13.2, 17.6, and 22 ms; and scan time = 3 min 40 sec; 5) 3D UTE-Cones-MT: TR = 100 ms; TE = 32 μs; flip angle = 7°; Nsp = 11; three MT powers = 500°, 1000°, and 1500°; and five MT frequency offsets = 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50 kHz; with scan time of 58 seconds per acquisition. The total acquisition time for the five types of UTE sequences was around 50 minutes.

All the quantitative UTE data, including 3D UTE-Cones-AFI, 3D UTE-Cones-VFA, 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ, 3D UTE-Cones-T2*, and 3D UTE-Cones-MT, were acquired. First, we scanned the knee specimens without any motion. Then, during pre-selected time points, we introduced random motion (i.e., translational and rotational motion, as well as flexion and extension) to simulate inter-scan motion. The translational range was around 20 millimeters. The degree of rotational motion, flexion, and extension was about 15°. Quantitative UTE processing was performed for all biomarkers before and after elastix motion registration, which was based on ITK (19). The elastix software consists of a collection of algorithms that are commonly used to solve medical image registration problems. In this paper, UTE-Cones-VFA images with TR = 20 ms and FA = 5° were treated as the fixed images, and the remaining sets of data (AdiabT1ρ, T2*, and MT) were treated as moving images. 3D non-rigid registration was applied to register the moving images to fixed images. In the 3D non-rigid registration, both rigid (affine) and non-rigid (B-spline) were applied in a two-staged approach to register the images. All registrations were driven by Advanced Mattes mutual information (25). The transformations were obtained by registration of the grayscale images (source: UTE images), then applied to the labeled images. Adaptive stochastic gradient descent optimizer was used to optimize both the affine and B-spline registration. Quantitative UTE values before and after motion correction were compared.

For the 15 healthy volunteers, the degree of motion differed for each volunteer. We did not control the degree of motion. The degree of rotational motion, flexion, and extension was about 0–10°. The elastix motion registration was applied to the 3D UTE-Cones data before quantification. Rigid registration was first carried out to correct for translations and rotations, subsequently followed by non-rigid registration for further fine adjustment (such as scaling and shearing). The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used for non-linear fitting of UTE-Cones data based on prior reported equations. The analysis algorithms written in Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) were applied to the DICOM images obtained using the 3D UTE-Cones protocol described above. Manually drawn regions-of-interest for the 15 in vivo knees were used to measure the mean and standard deviation for T1, T1ρ, T2*, MTR, and f of various tissues, including the articular cartilage (including femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, and patellar cartilage), meniscus, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle. After fitting was completed, goodness of fit statistics (i.e., root mean squared error (RMSE)) was computed.

The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging is well known (26). Since the 3D UTE-Cones-AFI technique provides accurate B1 measurement for both short and long T2 tissues, it allows the investigation of the impact of B1 inhomogeneity on various quantitative 3D UTE-Cones measurements including T1, T1ρ, and f. The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging was investigated on the knee specimen and 15 healthy volunteers with motion correction.

Results

Figure 2 demonstrates the effectiveness of the elastix motion correction algorithm when applied to representative 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ images of a cadaveric knee joint before and after manually induced motion. We observed that the difference images with motion correction achieved near noise level, demonstrating that near perfect registration was achieved. Moreover, we observed significant residual signals in the difference images without motion correction.

Figure 2.

3D UTE-Cones AdiabT1ρ imaging of a cadaveric human knee joint (31-year-old male donor) without motion (A), the signal differences between static and moved images without elastix motion correction (B) and with elastix motion correction (C). Near noise level signal was observed after motion correction, suggesting the accuracy of the motion correction technique.

Figure 3 shows 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ fitting before and after motion for the same cadaveric knee joint. Without motion, AdiabT1ρ values were achieved with a T1ρ of 13.5 ± 0.9 ms for the quadriceps tendon, 38.2 ± 4.3 ms for the PCL, 21.0 ± 1.1 ms for the meniscus, and 56.4 ± 4.0 ms for the patellar cartilage. When motion was introduced during the scans, RMSE increased to 20.71% for the quadriceps tendon, 8.71% for the PCL, 19.12% for the meniscus, and 10.33% for the patellar cartilage. However, after elastix motion registration, very similar AdiabT1ρ values were achieved for the quadriceps tendon (T1ρ = 13.0 ± 0.7 ms), the PCL (T1ρ = 39.2 ± 5.2 ms), the meniscus (T1ρ=24.4 ± 1.6 ms), and the patellar cartilage (T1ρ = 61.3 ± 5.2 ms) when compared to the non-motion condition. RMSE decreased to 3.30%, 3.80%, 3.77%, and 4.54% respectively. Supporting Table S1 summarizes RMSE measurements for T1, T1ρ, and f fitting for various tissues of the cadaveric knee joint. Overall, RMSE was greatly reduced for all the UTE biomarkers of all knee joint tissues following elastix motion correction.

Figure 3.

3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ imaging of a cadaveric knee joint with representative regions of interest (ROI) (A-D), along with the corresponding fitting curves for quadriceps tendon, PCL, meniscus, and patellar cartilage before motion (E-H), after motion without elastix motion correction (I-L), and with elastix motion correction (M-P). AdiabT1ρ values obtained using elastix motion correction are comparable to the non-motion condition.

Figure 4 shows 3D UTE-Cones-MT modeling before and after motion for the cadaveric knee joint. Without motion, f values were measured for the quadriceps tendon (f = 20.7 ± 1.6%), the PCL (f = 15.2 ± 1.0%), the meniscus (f = 22.9 ± 1.2%), and the patellar cartilage (f = 10.3 ± 0.5%). When motion was introduced during the scans, RMSE increased to 39.78% for the quadriceps tendon, 24.57% for the PCL, 28.82% for the meniscus, and 19.98% for the patellar cartilage. After elastix motion registration, very similar macromolecular fractions were achieved for the quadriceps tendon (f = 20.4 ± 1.5%), the PCL (f = 15.0 ± 0.9%), the meniscus (f = 21.6 ± 1.4%), and the patellar cartilage (f = 9.7 ± 0.7%) when compared with the non-motion condition. RMSE decreased to 1.83%, 1.36%, 1.61%, and 1.14%, respectively.

Figure 4.

3D UTE-Cones-MT imaging of a cadaveric knee joint with representative ROI (A-D), the corresponding fitting curves for quadriceps tendon, PCL, meniscus, and patellar cartilage before motion (E-H), after motion without elastix motion correction (I-L), and with elastix motion correction (M-P). UTE-MT modeling parameters obtained using elastix motion correction are comparable to the non-motion condition.

Table 1 summarizes mean and standard deviation values of T1, T1ρ, f, and MTR for articular cartilage, menisci, PCL, ACL, tendon, and muscle over three cadaveric knee joint specimens before and after elastix motion registration. The results demonstrate the efficiency of the elastix motion registration algorithm.

Table 1.

Mean T1, T1ρ, macromolecular fraction (f), and MTR values for various cadaveric human knee joint tissues including cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons, and muscle before and after elastix motion registration. The values in parentheses are percentage changes relative to the quantitative values before motion.

| T1 (ms) | T1ρ (ms) | f (%) | MTR (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before motion | After motion | After registration | Before motion | After motion | After registration | Before motion | After motion | After registration | Before motion | After motion | After registration | |

| Meniscus | 596.4±1.9 | 707.8±7.1 (18.68%) | 626.8±10.2 (5.10%) | 22.4±1.1 | 40.3±13.6 (79.91%) | 24.4±1.7 (8.93%) | 21.6±1.0 | 28.5±20.2 (31.94%) | 21.0±0.6 (2.78%) | 52.5±0.3 | 23.9±17.7 (54.48%) | 53.0±0.7 (0.95%) |

| Femoral Cartilage | 723.8±16.2 | 990.9±286.5 (36.90%) | 652.2±10.1 (9.89%) | 42.7±1.2 | 21.6±1.3 (49.41%) | 38.5±0.2 (9.84%) | 16.3±1.8 | 18.2±12.3 (11.66%) | 15.2±1.1 (6.75%) | 40.6±1.3 | 13.8±7.1 (66.01%) | 43.8±1.0 (7.88%) |

| Tibial Cartilage | 713.5±27.4 | 1246.2±360.2 (74.66%) | 643.3±5.3 (9.84%) | 36.9±3.8 | 31.2±7.0 (15.45%) | 34.1±5.5 (7.59%) | 16.1±1.2 | 20.7±12.7 (28.57%) | 14.6±0.4 (9.32%) | 43.0±1.1 | 15.5±1.9 (63.95%) | 45.0±0.3 (4.65%) |

| Patellar Cartilage | 898.3±9.9 | 658.5±26.5 (26.69%) | 815.6±11.2 (9.21%) | 57.3±4.1 | 34.5±3.9 (39.79%) | 53.6±6.0 (6.46%) | 12.3±1.4 | 23.7±20.9 (92.68%) | 11.2±0.5 (8.94%) | 42.1±1.7 | 2.6±3.1 (93.82%) | 44.1±0.4 (4.75%) |

| Quadriceps tendon | 555.8±11.2 | 457.9±2.2 (17.61%) | 502.3±2.1 (9.63%) | 14.6±0.9 | 11.2±0.4 (23.29%) | 14.0±0.7 (4.11%) | 19.5±0.9 | 23.2±0.9 (18.97%) | 19.8±1.0 (1.54%) | 48.3±5.8 | 85.7±1.4 (77.43%) | 51.5±6.3 (6.63%) |

| Patellar Tendon | 506.1±16.8 | 109.0±187.6 (78.46%) | 531.9±16.2 (5.10%) | 19.7±1.0 | 13.3±0.5 (32.49%) | 17.8±0.3 (9.64%) | 25.1±2.4 | 10.2±0.0 (59.36%) | 27.5±3.8 (9.56%) | 43.1±2.1 | 79.6±1.8 (84.69%) | 47.3±2.9 (9.74%) |

| ACL | 736.2±82.6 | 507.1±32.1 (31.12%) | 665.1±8.2 (9.66%) | 29.6±3.9 | 26.8±4.1 (9.46%) | 29.0±3.7 (2.03%) | 14.6±2.3 | 9.9±5.7 (32.19%) | 13.3±1.3 (8.90%) | 45.8±5.3 | 43.9±10.9 (4.15%) | 48.7±5.1 (6.33%) |

| PCL | 710.7±46.8 | 495.9±3.0 (30.22%) | 648.5±13.1 (8.75%) | 33.9±4.2 | 26.8±2.0 (20.94%) | 34.7±5.8 (2.36%) | 16.7±0.8 | 6.7±6.5 (59.88%) | 15.4±0.7 (7.78%) | 46.5±0.3 | 35.7±13.3 (23.23%) | 48.1±1.2 (3.44%) |

| Muscle | 1058.9±4.7 | 1168.7±31.7 (10.37%) | 993.1±15.3 (6.21%) | 63.3±1.3 | 45.0±10.3 (28.91%) | 63.2±4.5 (0.16%) | 7.9±0.3 | 6.0±2.5 (24.05%) | 7.9±0.3 (0.00%) | 37.0±0.1 | 9.9±8.2 (73.24%) | 40.3±0.4 (8.92%) |

Figure 5 shows representative 3D UTE-AdiabT1ρ fitting as well as 3D UTE-Cones-MT modeling of the femoral condyle for a 32-year-old female volunteer before and after elastix motion registration. Before elastix motion registration, the femoral condyle showed AdiabT1ρ and f values of 20.7 ± 4.7 ms and 39.7 ± 13.3%, with RMSE of 6.22% and 2.36%, respectively. After elastix motion registration, AdiabT1ρ and f values changed to 39.1 ± 3.9 ms and 9.8 ± 0.9%, with RMSE decreased to 3.28% and 0.70%, respectively. The elastix motion registration reduced the MT fitting error by more than four-fold.

Figure 5.

A representative slice from 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ (A) and UTE-Cones-MT (B) imaging of the knee joint of a 32 year-old female volunteer, and an ROI in the femoral condyle cartilage used for AdiabT1ρ fitting before (C) and after (D) elastix motion registration as well as MT modeling before (E) and after (F) elastix motion registration. RMSE values were much higher for the fitting curves before motion correction, and much lower after motion correction. More reasonable AdiabT1ρ of 39.1 ± 3.9 ms and f of 9.8 ± 0.9% were achieved for articular cartilage in the femoral condyle after elastix motion registration.

Table 2 summarizes mean and standard deviation of T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and f for articular cartilage, menisci, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle of 15 healthy volunteers before and after elastix motion registration. Some values are significantly different between the postprocessing with and without image co-registration, even though only a few volunteers moved during the scan.

Table 2.

Mean T1, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, MT modeling of macromolecular fraction (f), and T2* for various knee joint tissues including meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle of 15 healthy volunteers before and after elastix motion registration.

| T1 (ms) | T1ρ(ms) | MTR (%) | f (%) | T2*(ms) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before registration | After registration | Before registration | After registration | Beforeregistration | Afterregistration | Before registration | After registration | Before registration | After registration | |

| Meniscus | 820.1±56.7 | 820.1±57.9 | 20.1±2.1 | 20.9±1.5*1 | 57.0±4.6 | 58.1±3.1 | 19.1±2.0 | 18.9±1.5 | 11.1±7.9 | 9.0±1.4 |

| Femoral Cartilage | 1118.1±129.4 | 1152.1±116.0 | 42.5±8.3 | 44.2±7.1 | 47.3±7.0 | 46.7±5.7 | 11.3±1.5 | 10.7±1.6*5 | 33.3±8.9 | 39.6±7.9*7 |

| Tibial Cartilage | 957.2±114.9 | 943.8±93.2 | 33.8±5.3 | 32.6±4.6 | 48.6±4.4 | 49.7±4.0 | 15.5±6.2 | 14.3±2.7 | 24.0±7.2 | 20.2±4.2*8 |

| Patellar Cartilage | 1094.7±110.5 | 1105.2±117.0 | 46.1±5.8 | 46.2±5.1 | 39.3±8.1 | 41.1±5.3 | 9.5±2.0 | 10.1±1.8*6 | 34.6±8.8 | 36.9±8.4*9 |

| Quadriceps tendon | 800.5±62.3 | 802.6±59.6 | 13.2±2.3 | 13.3±2.1 | 47.6±8.8 | 52.6±7.3*2 | 18.9±6.2 | 17.3±2.1 | 10.5±2.8 | 10.7±2.8 |

| Patellar Tendon | 646.6±53.1 | 641.6±54.7 | 9.9±1.6 | 9.9±1.5 | 43.5±8.7 | 46.3±6.1 | 23.7±9.3 | 20.2±2.7 | 5.8±2.3 | 5.7±2.3 |

| ACL | 942.6±138.6 | 922.3±119.1 | 25.5±4.2 | 25.8±3.9 | 47.1±6.6 | 48.4±6.5*3 | 13.7±2.2 | 14.1±2.2 | 16.4±4.0 | 16.3±4.1 |

| PCL | 838.6±57.6 | 839.4±54.0 | 17.2±3.2 | 17.4±3.0 | 53.8±5.9 | 55.6±5.3*4 | 16.1±3.6 | 17.1±1.8 | 9.2±1.5 | 8.8±1.6 |

| Muscle | 1389.9±71.2 | 1385.0±69.9 | 43.3±2.9 | 43.3±2.9 | 47.1±2.0 | 47.3±2.0 | 7.7±0.6 | 7.8±0.6 | 31.2±3.4 | 31.1±3.5 |

p=0.026;

p=0.000;

p=0.035;

p=0.010;

p=0.029;

p=0.007;

p=0.007;

p=0.004;

p=0.006.

The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging is shown in Supporting Table S2 for the ex vivo study and in S3 for the in vivo study.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the 3D UTE-Cones sequences provide high SNRs for all the major tissues in the knee joint. Together with the elastix motion registration algorithm, the proposed sequences can quantitatively measure T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and f for both short and long T2 tissues in the knee joint including articular cartilage, menisci, ACL, PCL, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, and muscle. The elastix motion registration method can reliably correct motion which occurs between the repeated UTE measurements. Those UTE measurements allow for the first comprehensive quantitative evaluation of the knee joint using a truly “whole joint” approach (27). This new protocol may provide more sensitive evaluation of knee degeneration in its early stages than conventional clinical imaging sequences, which are largely focused on the superficial layers of articular cartilage and provide little or no quantitative information regarding the short T2 tissues or tissue components (6).

UTE-Cones biomarkers including T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and f for all the soft tissues in the human knee joint are largely consistent with previously reported 3T studies. For example, our 3D UTE-Cones T1 values for long T2 tissues such as cartilage (944~1152 ms) and muscle (~1385 ms) were close to those reported by Jordan et al., who reported a mean T1 of 1016 ms for cartilage and 1256 ms for muscle (28), and to those reported by Stanisz et al., who reported a T1 value of 1156 ms for cartilage and 1412 ms for muscle (29). Neither Jordan et al. nor Stanisz et al. reported T1 values for menisci, ligaments, and tendons, as their sequences had too long TEs to detect enough signal from those short T2 tissues. Our 3D UTE-Cones T2* values for cartilage (20~39 ms) were also largely consistent with those reported by Williams et al. (20~30 ms) (30, 31). The measured AdiabT1ρ values for cartilage (33~46 ms), meniscus (~21 ms), quadriceps tendon (~13 ms), patellar tendon (~10 ms), ACL (~26 ms), PCL (~17 ms), and muscle (~43 ms) were also consistent with previous reports of 36–45 ms for cartilage, 18~23 ms for meniscus,13 ms for quadriceps tendon, 10 ms for patellar tendon, 35 ms for ACL, 22 ms for PCL, and 43 ms for muscle (11).

Although cones acquisitions are often believed to be less sensitive to motion artifact than cartesian acquisitions, the motion artifacts may still impact quantitative measures. The elastix motion registration is critical for robust quantitative evaluation of various knee joint tissues (25). Our preliminary studies suggest that knee joint motion occurring during the relatively long scan time involved in these sequences could be well compensated for, as demonstrated by the near noise level signal in the difference image between original and motion-corrected images. In the specimen study, significantly different measurements were derived for the knee joint tissues with and without manually induced motion. However, consistent measurements were achieved when the elastix motion registration was applied before data analyses compared with the non-motion results, demonstrating the accuracy of the motion correction and further supporting the feasibility of comprehensive quantitative 3D UTE-Cones evaluation of knee joint tissues in vivo.

We observed greater errors for thinner tissues such as articular cartilage and fewer errors for thicker tissues such as muscle. It is therefore likely that the elastix motion registration algorithm is less robust for 3D anisotropic imaging (e.g., our 3D UTE imaging protocol used an in-plane resolution of 0.586 mm with a much thicker slice of 3 mm). A more robust motion registration algorithm, as well as more isotropic imaging (e.g., a thinner slice), would help in reducing quantification errors associated with motion. However, the errors are smaller than changes produced by knee joint degeneration, which are typically in the range of 10–30% (7). Notably, the elastix motion registration cannot correct intra-scan motion, which leads to degradation of the UTE image quality and to errors in quantification. UTE data acquisition with incorporated motion navigation is needed to correct for this type of motion and to further improve the quantification accuracy.

Degeneration of the knee joint or osteoarthritis (OA) is a heterogeneous and multifactorial disease associated with progressive loss of articular cartilage. It is much more than a cartilage disease, however, as it involves multiple joint tissues, including short T2 tissues (27,32–37). When one tissue begins to deteriorate, it often affects surrounding tissues, contributing to overall failure of the joint (2). From this point of view, UTE sequences have the potential to resolve a major problem for conventional clinical MRI evaluation of abnormalities in the early stages of OA.

Another advantage of the new protocol is the fact that many of the UTE biomarkers are less sensitive to fiber orientation relative to the B0 field, i.e. the magic angle effect. Conventional T2 and CW-T1ρ measurements have been shown to be sensitive to the magic angle effect (38–41). When the fibers are re-oriented near 55° relative to the B0 field, T2 and CW-T1ρ can increase by more than 100%, which can be higher than the increase attributed to tissue degeneration (42). This is a major limitation in employing clinical T2 and CW-T1ρ measurements to detect early OA. On the other hand, most of our UTE biomarkers, such as T1 (10), AdiabT1ρ (11), MTR, and MT modeling of f (12, 21–23), are much less sensitive to the magic angle effect. The proposed 3D UTE-Cones-AFI-VFA technique allows, for the first time, robust evaluation of T1 for short T2 tissues in the knee joint without compromise from RF inhomogeneity. Prior studies have shown that T1 is nearly magic angle-independent (15). The derived T1 value is an important input for both quantification of AdiabT1ρ and MT modeling (11, 12). 3D UTE-Cones-AdiabT1ρ has also shown reduced sensitivity to the magic angle effect (11, 16). 3D UTE-Cones-MTR and particularly UTE-Cones-MT modeling of water and macromolecular proton fractions and exchange rates are insensitive to the magic angle effect (17, 21).

There are several limitations of this study. First, only cadaveric knee joint specimens and healthy volunteers were recruited. OA patients, with whom motion is more likely to occur, were not scanned; therefore, the clinical significance of our proposed technique remains to be demonstrated. However, the preliminary results from this study clearly demonstrate the feasibility of in vivo studies of the knee joint, and we expect no technical difficulty running the same comprehensive UTE imaging protocol on OA patients. Second, the quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging protocol is relatively long, taking about 50 minutes in total. Further optimization of the protocol, especially the combination of parallel imaging, compressed sensing, and/or deep learning, may significantly reduce the total scan time (e.g., 25 minutes when using an acceleration factor of 2), thus facilitating clinical translation of those techniques (43, 44). Third, the advantages of the comprehensive quantitative UTE imaging protocol over a conventional clinical imaging protocol remain to be demonstrated, although our preliminary findings suggest obvious benefits, as UTE sequences can be used to evaluate both short and long T2 tissues and they are less sensitive to the magic angle effect. Fourth, only inter-scan motion correction was performed in our study. Intra-scan motion was not considered, as most of the quantitative UTE scans were around 3 minutes or shorter (e.g., 58 seconds for each UTE-MT acquisition, 2 minutes 22 seconds for each UTE-Cones-VFA acquisition). The whole quantitative UTE protocol lasts around 50 minutes, which is much longer than each single scan, and is thus more prone to inter-scan motion artifacts. As a result, intra-motion is expected to be much smaller than inter-scan motion. More advanced techniques incorporating motion registration in UTE-Cones data acquisition would allow intra-scan motion correction, further improving the robustness of these quantitative UTE techniques. Fifth, we only performed the first order eddy currents correction by running calibration on a homogenous water phantom to calculate the constant delay in Gx, Gy, and Gz. Correction of higher order eddy currents, including the distortion of kx, ky, and kz can be performed by measuring the k-space trajectory with techniques such as the Duyn’s method (45). This remains to be implemented for more accurate quantitative 3D UTE-Cones imaging.

Conclusion

The 3D UTE-Cones quantitative imaging techniques (i.e. T1, T2*, AdiabT1ρ, MTR, and MT modeling) together with elastix motion correction provide robust volumetric measurement of relaxation times, MTR, and f of both short and long T2 tissues in the knee joint.

Supplementary Material

Table S1.RMSE values for T1, T1ρ, and f fitting for various cadaveric human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle before and after elastix motion registration.

Table S2.The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones measurements of T1, T1ρ, and f of various cadaveric human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle.

Table S3.The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones measurements of T1, T1ρ, and f of human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle (averaged over 15 healthy volunteers).

Acknowledgements /Grant Support:

The authors acknowledge grant support from NIH (1 R01 AR062581-01A1 and 1 R01 AR068987-01) and the VA (I01CX001388).

Abbreviations

- 3D

three dimensional

- UTE

ultrashort echo time

- AFI

actual flip angle

- AdiabT1ρ

adiabatic T1ρ

- MT

magnetization transfer

- MTR

magnetization transfer ratio

- f

macromolecular proton fraction

- RMSE

root mean square errors

- CW-T1ρ

continuous wave T1ρ

- VFA

variable flip angles

- AFP

adiabatic full passage

- ACL

anterior cruciate ligament

- PCL

posterior cruciate ligament

- ITK

Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit

- IRB

institutional review board

- FOV

field of view

- TSL

spin-locking time

- OA

osteoarthritis

- ROI

regions of interest

References

- 1.Buckwalter JA, Martin J. Degenerative joint disease. Clin Symp 1995; 47:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt KD, Radin EL, Dieppe PA, Putte L. Yet more evidence that osteoarthritis is not a cartilage disease (Editorial). Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1261–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, Tu X, Amin S, Clancy M, Guermazi A, Grigorian M, Gale D, Felson DT. The association of meniscal pathologic changes with cartilage loss in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan AL, Toumi H, Benjamin M, Grainger AJ, Tanner SF, Emery P, McGonagle D. Combined high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histological examination to explore the role of ligaments and tendons in the phenotypic expression of early hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1267–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to Ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2003; 27:825–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckstein F, Burstein D, Link TM. Quantitative MRI of cartilage and bone: degenerative changes in osteoarthritis. NMR in Biomedicine 2006; 19:822–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosher TJ, Zhang Z, Reddy R, Boudhar S, Milestone BN, Morrison WB, Kwoh CK, Eckstein F, Witschey WR, Borthakur A. Knee articular cartilage damage in osteoarthritis: analysis of MR image biomarker reproducibility in ACRIN-PA 4001 multicenter trial. Radiology 2011; 258:832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duvvuri U, Charagundla SR, Kudchodkar SB, Kaufman JH, Kneeland JB, Rizi R, Leigh JS, Reddy R. Human knee: in vivo T1ρ-weighted MR imaging at 1.5 T – preliminary experience. Radiology 2001; 220:822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Ma B, Link TM, Castillo D, Blumenkrantz G, Lozano J, Carballido-Gamio J, Ries M, Majumdar S. In vivo T1ρ and T2 mapping of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis of the knee using 3T MRI. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2007; 15:789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma YJ, Zhao W, Wan L, Guo T, Searleman A, Jang H, Chang EY, Du J. Whole knee joint T1 values measured in vivo at 3T by combined 3D ultrashort echo time cones actual flip angle and variable flip angle methods. Magn Reson Med 2019; 81(3):1634–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma YJ, Carl M, Searleman A, Lu X, Chang EY. Du J. 3D adiabatic T1ρ prepared ultrashort echo time cones sequence for whole knee imaging. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80:1429–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma YJ, Chang EY, Carl M, Du J. Quantitative magnetization transfer ultrashort echo time imaging using a time-efficient 3D multispoke Cones sequence. Magn Reson Med 2018; 79:692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma YJ, Lu X, Carl M, Zhu Y, Szeverenyi NM, Bydder GM, Chang EY, Du J. Accurate T1 mapping of short T2 tissues using a three-dimensional ultrashort echo time cones actual flip angle imaging - variable repetition time (3D UTE-Cones AFI-VTR) method. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80:598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams A, Qian Y, Golla S, Chu CR. UTE-T2* mapping detects sub-clinical meniscus injury after anterior cruciate ligament tear. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20:486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Kim JK, Bronskill MJ. Anisotropy ofNMR properties of tissues. Magn Reson Med 1994; 32:592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hänninen N, Rautiainen J, Rieppo L, Saarakkala S, Nissi MJ. Orientation anisotropy of quantitative MRI relaxation parameters in ordered tissue. Scientific Reports 2017; 7:9606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma YJ, Shao H, Du J, Chang EY. Ultrashort Echo Time Magnetization Transfer (UTE-MT) Imaging and Modeling: Magic Angle Independent Biomarkers of Tissue Properties. NMR Biomed 2016; 29:1546–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raynauld JP, Pelletier JM, Berthiaume MJ, Labonte F, Beaudoin G, de Guise JA, Bloch DA, Choquette D, Haraoui B, Altman RD, Hochberg MC, Meyer JM, Cline GA, Pelletier JP. Quantitative magnetic resonane imaging evaluation of knee osteoarthritis progression over two years and correlation with clinical symptoms and radiologic changes. Arthritis Rheumatology 2004; 50:476–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Periaswamy S, Farid H. Elastic registration in the presence of intensity variations. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2003; 22:865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carl M, Bydder GM, Du J. UTE imaging with simultaneous water and fat signal suppression using a time-efficient multispoke inversion recovery pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med 2016; 76:577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y, Cheng X, Ma YJ, Wong J, Xie Y, Du J, Chang EY. Rotator Cuff Tendon Assessment Using Magic-Angle Insensitive 3D Ultrashort Echo Time Cones Magnetization Transfer (UTE-Cones-MT) Imaging and Modeling with Histological Correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 48:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen B, Zhao Y, Cheng X, Ma YJ, Chang EY, Kavanaugh A, Liu S, Du J. Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time Cones (3D UTE-Cones) magnetic resonance imaging of enthesis and tendons. Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 49:4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen B, Cheng X, Dorthe EW, Zhao Y, D’Lima D, Bydder GM, Liu S, Du J, Ma YJ. Evaluation of normal cadaveric Achilles tendon and enthesis with ultrashort echo time (UTE) magnetic resonance imaging and indentation testing. NMR in Biomed 2019; 32:e4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang EY, Du J, Iwasaki K, Biswas R, Statum S, He Q, Bae WC, Chung CB. Single- and bi-component T2* analysis of tendon before and during tensile loading, using UTE sequences. J Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2014; 42:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JPW. Elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2010; 29:196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarnykh VL. Actual flip-angle imaging in the pulsed steady state: a method for rapid three-dimensional mapping of the transmitted radiofrequency field. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi D, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ. Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: imaging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011; 19:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan CD, Saranathan M, Bangerter NK, Hargreaves BA, Gold GE. Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0T and 7.0T: a comparison of relaxation times and image contrast. Eur J Radiol. 2013; 82: 734–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanisz GJ, Odrobina EE, Pun J, Escaravage M, Graham SJ, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. T1, T2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2005; 54: 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams A, Qian YX, Chu CR. UTE-T2* mapping of human articular cartilage in vivo: a repeatability assessment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011; 19(1): 84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams A, Qian Y, Bear D, Chu CR. Assessing degeneration of human articular cartilage with ultra-short echo time (UTE) T2* mapping. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010; 18(4): 539–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Wei HW, Yu TC, Cheng CK. Parametric analysis of the stress distribution on the articular cartilage and subchondral bone. Biomed Mater Eng. 2007;17(4):241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radin EL, Rose RM. Role of subchondral bone in the initiation and progression of cartilage damage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986; (213):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDermott I Meniscal tears, repairs and replacement: their relevance to osteoarthritis of the knee. Br J Sports Med. 2011; 45(4):292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radin EL, de Lamotte F, Maquet P. Role of the menisci in the distribution of stress in the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984; (185):290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assimakopoulos AP, Katonis PG, Agapitos MV, Exarchou EI. The innervation of the human meniscus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992; (275):232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thijs Y, Witvrouw E, Evens B, Coorevits P, Almqvist F, Verdonk R. A prospective study on knee proprioception after meniscal allograft transplantation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007; 17(3):223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erickson SJ, Prost RW, Timins ME. The “magic angle” effect: background physics and clinical relevance. Radiology 1993; 188:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubenstein JD, Kim JK, Morova-Prozner I, Stanchev PL, Henkelman RM. Effects of collagen orientation on MR imaging characteristics of bovine articular cartilage. Radiology 1993; 188:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, Lust G. Origin of cartilage laminae in MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 1997; 7:887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mlynarik V, Szomolanyi P, Toffanin R, Vittur F, Trattnig S. Transverse relaxation mechanisms in articular cartilage. J Magn Reson 2004; 169(2):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao H, Pauli C, Li S, Ma Y, Tadros AS, Kavanaugh A, Chang EY, Tang G, Du J. Magic angle effect plays a major role in both T1rho and T2 relaxation in articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017; 25:2022–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 2007; 58(6):1182–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu B, Liu JZ, Cauley SF, Rosen BR, Rosen MS. Image reconstruction by domain-transform manifold learning. Nature 2018; 555(7697):487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duyn JH, Yang YH, Frank JA, Veen JW. Simple correction method for k-space trajectory deviations in MRI. J Magn Reson 1998; 132:150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.RMSE values for T1, T1ρ, and f fitting for various cadaveric human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle before and after elastix motion registration.

Table S2.The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones measurements of T1, T1ρ, and f of various cadaveric human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle.

Table S3.The impact of B1 inhomogeneity on quantitative 3D UTE-Cones measurements of T1, T1ρ, and f of human knee joint tissues including the meniscus, femoral cartilage, tibial cartilage, patellar cartilage, quadriceps tendon, patellar tendon, ACL, PCL, and muscle (averaged over 15 healthy volunteers).