Abstract

J. Neurochem. (2011) 116, 105–121.

Abstract

This study examines the Cav1 isoforms expressed in mouse chromaffin cells and compares their biophysical properties and roles played in cell excitability and exocytosis. Using immunocytochemical and electrophysiological techniques in mice lacking the Cav1.3α1 subunit (Cav1.3−/−) or the high sensitivity of Cav1.2α1 subunits to dihydropyridines, Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels were identified as the only Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells. Cav1.3 channels were activated at more negative membrane potentials and inactivated more slowly than Cav1.2 channels. Cav1 channels, mainly Cav1.2, control cell excitability by functional coupling to BK channels, revealed by nifedipine blockade of BK channels in wild type (WT) and Cav1.3−/− cells (53% and 35%, respectively), and by the identical change in the shape of the spontaneous action potentials elicited by the dihydropyridine in both strains of mice. Cav1.2 channels also play a major role in spontaneous action potential firing, supported by the following evidence: (i) a similar percentage of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells fired spontaneous action potentials; (ii) firing frequency did not vary between WT and Cav1.3−/− cells; (iii) mostly Cav1.2 channels contributed to the inward current preceding the action potential threshold; and (iv) in the presence of tetrodotoxin, WT or Cav1.3−/− cells exhibited spontaneous oscillatory activity, which was fully abolished by nifedipine perfusion. Finally, Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels were essential for controlling the exocytotic process at potentials above and below −10 mV, respectively. Our data reveal the key yet differential roles of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels in mediating action potential firing and exocytotic events in the neuroendocrine chromaffin cell.

Keywords: action potentials, BK channels, Cav1 channels, exocytosis; chromaffin cells, pacemaker

Abbreviations used:

- BK

large conductance Ca2+‐ and voltage‐dependent K+ channels

- DHP

dihydropyridine

- MHV

mouse hepatitis virus

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- SPF

specific pathogen free

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- ω‐CTX‐GVIA

ω‐conotoxin GVIA

- ω‐CTX‐MVIIC

ω‐conotoxin MVIIC

- WT

wild type

Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels are Cav1 channel subtypes widely expressed in neuronal and neuroendocrine cells, as well as in electrically excitable cells in the cardiovascular system (Hell et al. 1993; Platzer et al. 2000; Namkung et al. 2001; Brandt et al. 2003; Mangoni et al. 2003). Both subtypes are found in the same cells in the brain (Hell et al. 1993), heart atria (Mangoni et al. 2003) or pancreatic islet cells (Vignali et al. 2006). Though Cav1.2 are the most abundant (Hell et al. 1993; Sinnegger‐Brauns et al. 2004), the two channel types mainly differ in their sensitivity to dihydropyridines (DHPs) and voltage dependence of activation.

Cav1.2 channels exhibit a higher sensitivity than Cav1.3 channels to DHPs. In heterologous systems their blockade is almost complete with 3 μM nimodipine (Xu and Lipscombe 2001), and fully achieved with 300 nM isradipine (Koschak et al. 2001). Cav1.3 channels are activated at negative membrane potentials (Platzer et al. 2000; Brandt et al. 2003). Relative to Cav1.2 channels, their activation voltage seems to be more negative in native cells (Mangoni et al. 2003; Olson et al. 2005), or heterologous systems (Koschak et al. 2001; Xu and Lipscombe 2001).

In the neuroendocrine chromaffin cell, Cav1 channels contribute to spontaneous action potential firing, mainly the Cav1.3 subtype (Marcantoni et al. 2010). This channel subtype is thought to mediate basal neurotransmitter release (Zhou and Misler, 1995). In addition, it is known that Cav1 channels are coupled to large conductance Ca2+‐ and voltage‐dependent K+ (BK) channels (Prakriya and Lingle 1999), especially the Cav1.3 subtype (Marcantoni et al. 2010). Cav1 channels control neurotransmitter release (López et al. 1994; Aldea et al. 2002; Polo‐Parada et al. 2006) and are inhibited or potentiated by neurotransmitters or secondary messengers (Albillos et al. 1996; Carabelli et al. 2001; Cesetti et al. 2003).

The aim of the present study was to gain insight into the different roles played in cell excitability and exocytosis by Cav1 channel subtypes in neuroendocrine cells. To this end, immunocytochemical and ‘patch‐clamp’ techniques were conducted in chromaffin cells of the adrenal gland medulla of two strains of transgenic mice: one lacking the Cav1.3α1 subunit (Cav1.3−/−) (Platzer et al. 2000), and the other lacking the high sensitivity of Cav1.2α1 subunits to DHPs (Cav1.2DHP−/−) (Sinnegger‐Brauns et al. 2004).

Two abstracts for this study have been published elsewhere (Albillos et al. 2006; Pérez‐Alvarez et al. 2006).

Materials and methods

Animals

The generation and characterization of Cav1.3−/− and Cav1.2DHP−/− mice have been described previously (Platzer et al. 2000; Sinnegger‐Brauns et al. 2004). Both mouse lines were crossed with C57BL/6J mice and bred under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions after embryos were transferred under sterile conditions to SPF mothers. Animals were handled according to the guidelines of our Medical School’s Committee for Animal Care and Use.

Cav1.3−/− mice displayed normal sexual activity and reproduction, and lacked obvious anatomical abnormalities or major glucose metabolism disturbances. Cav1.3−/− mice were deaf because of the complete absence of Cav1 currents in cochlear inner hair cells and degeneration of outer and inner hair cells. Electrocardiogram recordings also revealed sinoatrial node dysfunction (bradycardia and arrhythmia) in the Cav1.3−/− mice (Platzer et al. 2000).

Genotyping

Genotypes were confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA isolated from mice tail‐tips by standard procedures, using a commercial PCR Mastermix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

For Cav1.3−/− mice, primers P1 (5′‐GCAAACTATGCAAGAGGCACCAGA‐3′), P2 (5′‐TTCCATTTGTCACGTCCTGCACCA‐3′) and P3 (5′‐TACTTCCATTCCACTATACTAATGCAGGCT‐3′), employed simultaneously, yielded product sizes of 450 bp for homozygous mice, 300 bp and 450 bp for heterozygous mice, and 300 bp for wild type (WT). The PCR conditions were: 92°C for 2 min, 54°C for 20 s, 72°C for 30 s, 92°C for 25 s, 54°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The last three temperature cycles were repeated 34 times. Final extension was conducted at 72°C for 7 min.

For Cav1.2DHP−/− mice, the first screening was based on confirmation of a remaining loxP site upstream of the mutation. The primers used were: Loxup (5′‐CAGCTCAGCAGATGTCACAGAGCACAC‐3′) and Loxdown (5′‐CCAGAGCCACACTGATGGAACTCATGG‐3′). Predicted fragment sizes were 290 bp for homozygous mice, 200 bp and 290 bp for heterozygous mice, and 200 bp for WT. The temperature cycles were: 92°C for 2 min, 92°C for 30 s, 65°C for 20 s, 72°C for 30 s. The three last steps were repeated 35 times and a final extension conducted at 72°C for 8 min.

To identify the T to Y mutation, two separate reactions were performed with primers CAAP and Screen 1, and primers CAAP and A1Cwt, respectively. The primer sequences were CAAP (5′‐TCTCTGTCCTGACTCGGAGGC‐3′), Screen 1 (5′‐GAACATGAACTGCAGCAGAGTGTA‐3′) and A1Cwt (5′‐GGCGAACATGAACTGCAGCAGAGTGGT‐3′). When the CAAP and Screen 1 primers were used, only products in homozygous and heterozygous samples (290 bp) were obtained. When the CAAP and a1Cwt primers were used, only products in heterozygous and WT samples (290 bp) were produced. The PCR protocol was the same as for the first screen using an annealing temperature of 63°C.

Isolation and culture of mouse chromaffin cells

Two‐ to three‐month‐old mice (male or female) were killed by cervical dislocation and cut to expose the peritoneal cavity. The adrenal glands were procured and placed in a Petri dish with Locke solution and kept on ice until their dissection. The composition of the Locke’s buffer was (in mM): 154 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 3.6 NaHCO3, 5.6 glucose, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.2). Under the microscope, the fatty tissue and cortex were dissected away with the help of tweezers and a scalpel on a Petri dish. The medullae were then incubated for 25 min in a solution containing 25 units/mL of papain at 37°C. Next, they were rinsed first in Locke’s buffer and then in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 5% foetal bovine serum. The tissue was then gently mechanically digested using a Pasteur pipette to obtain a homogeneous suspension. Finally, cells were plated on glass coverslips in 24‐well plates previously treated with polylysine (0.1 mg/mL). After 1 h, 1 mL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium was added to each well. Cells were then incubated at 37°C in a water‐saturated, 95% O2 and 5% CO2 atmosphere and used within 1–3 days of plating. The glands from one mouse were needed to prepare each 24‐well plate.

Electrophysiological recordings

The external solution used to measure Ca2+ currents in the perforated‐patch configuration was (in mM) (Solution 1): 5 CaCl2, 100 NaCl, 45 TEACl, 5.5 KCl, 0.2 d‐tubocurarine, 0.002 tetrodotoxin (TTX), 0.0002 apamin, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). Intracellular solution composition was (in mM) (Solution 2): 145 Csglutamate, 8 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 0.5 amphotericin B (Sigma‐Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) (pH 7.2).

To measure K+ currents or to perform action potential clamp in the voltage‐clamp configuration, and to record action potentials in the current‐clamp configuration, the external solution was (in mM) (Solution 3): 2 CaCl2, 145 NaCl, 5.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). Intracellular solution composition was (in mM) (Solution 4): 145 Kglutamate, 8 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 0.5 amphotericin B (pH 7.2).

An amphotericin B stock solution (50 mg/mL) was freshly prepared daily by ultrasonication in dimethyl sulphoxide and was kept protected from light. Pipettes were tip‐dipped in amphotericin‐free solution and back‐filled with freshly mixed intracellular amphotericin solution. The perfusion system, a multi‐barrelled glass pipette, was positioned close to the cell under examination to allow the complete exchange of solutions near the cell within 100 ms. The level of the bath fluid was continuously controlled using a home‐made fibre optics system, coupled to a pump that gently sucked the excess fluid.

To pharmacologically characterize the Ca2+ channels, each Ca2+ channel blocker was added sequentially and cumulatively for at least 4–5 min [except ω‐conotoxin‐MVIIC (ω‐CTX‐MVIIC) which was perfused for at least 14 min]: 3 μM nifedipine was used to block Cav1 channels, 1 μM ω‐conotoxin‐GVIA (ω‐CTX‐GVIA) to block Cav2.2 channels, and 3 μM ω‐CTX‐MVIIC to block Cav2.1 channels. Cells were considered insensitive to nifedipine when the Ca2+ charge density was inhibited by a percentage smaller than 10%. All toxins were purchased from Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan, except apamin and TTX, which were obtained from Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK. Nifedipine was purchased from Sigma.

Electrophysiological measurements were made using an EPC‐10 amplifier and PULSE software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) running on a PC computer. Pipettes of 2–3 MΩ resistance were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary tubes, partially coated with wax and fire polished. No liquid junction potential correction was used, because of uncertainties about its merits when the perforated‐patch configuration is employed (Albillos et al. 2000). Series resistance was 19 ± 0.6 MΩ (n = 195). Only recordings in which the leak current was lower than 20 pA were accepted. However, cell recordings that exhibited spontaneous action potential firing (no current injection) were included in the analysis when they showed a leak current lower than 5 pA.

Cell membrane capacitance (C m) changes were estimated by the Lindau‐Neher technique implemented in the ‘Sine + DC’ feature of the ‘PULSE’ lock‐in software. A 1 kHz, 70 mV peak‐to‐peak amplitude sinewave was applied at a holding potential (V h) of −80 mV. The C m increase produced in response to depolarizing pulses was calculated as the difference between the maximal C m obtained after a pulse and the baseline C m recorded before this pulse.

The voltage dependence of activation was determined from normalized conductance versus voltage curves, which were fitted according to eqn 1:

| (1) |

where G is defined as I peak/(V−E rev), G ‐50 is the G value obtained at −50 mV, G max is the maximal G value attained, V 1/2 is the voltage for half maximal activation, and k the slope factor of the Boltzmann function.

The input resistance of the cell membrane (R in) was calculated from the slope of the linear fit to current in the voltage range −80 to −50 mV (Moser 1998) to give values of 4 ± 0.5 GΩ (n = 15) and 4.1 ± 0.3 GΩ (n = 16) for the WT mice and Cav1.3−/− mice, respectively.

Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–24°C). Analysis of data was conducted using IGOR Pro software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). The non‐specific background current and C m recorded under 200 μM CdCl2 were subtracted off‐line from all current and C m traces. Unless otherwise stated, data are given as the mean ± SEM. Data were compared using the paired (when comparing values before and after treatment in the same cell) or unpaired Student’s t‐test (when comparing values from different cells).

Immunocytochemistry for the Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, and Cav1.4 subunits

Coverslips containing mouse chromaffin cells were washed in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 3.5%p‐formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min. After extensive washing, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100 for 15 min. The coverslips were then washed in PBS and incubated with Image Enhancer IT‐FX (Molecular Probes, Barcelona, Spain) for 30 min. After removal of this compound, the coverslips were again washed in PBS and incubated with the corresponding primary antibody for 3 h at 25°C. The primary antibodies (dilution 1 : 200) were goat polyclonal anti‐Cav1.1 and anti‐Cav1.4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), and rabbit polyclonal anti‐Cav1.2 and anti‐Cav1.3 (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel). After incubation, the coverslips were washed and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody for 45 min. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor‐594 (dilution 1 : 200, Molecular Probes), goat anti‐rabbit (to label Cav1.2 and Cav1.3) and rabbit anti‐goat (to label Cav1.1 and Cav1.4). Pre‐adsorption controls were performed using control antigens for each primary antibody employed, which effectively avoided staining of our samples ruling out the possibility of non‐specific staining. After mounting the coverslips, fluorescence was determined using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Results

Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels are the Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells: immunocytochemical characterization and sensitivity to DHPs

The first experiments, using both immunocytochemical and electrophysiological techniques (testing two concentrations of DHPs in the submicromolar and micromolar range), were designed to determine the Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells.

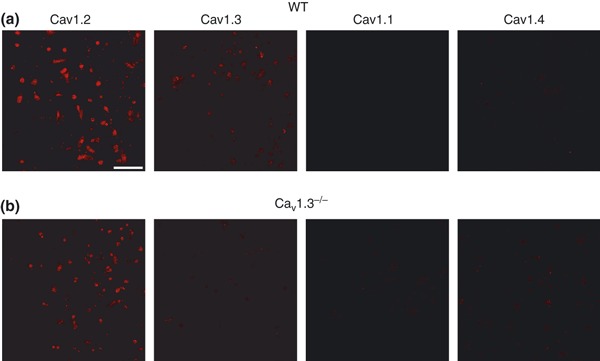

Immunocytochemical characterization of Cav1 channel subtypes

Antibodies against the different Cav1 channel subtypes (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, Cav1.4) were tested in chromaffin cells from WT mice (Fig. 1a). Cells were stained with antibodies against Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, but not against Cav1.1 and Cav1.4 channels. Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 antibodies were also tested in Cav1.3−/− cells. Labeling for Cav1.2 antibodies was exclusively observed (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells. Immunocytochemical characterization of Cav1 channel subtypes. (a–b) Confocal images of isolated mouse chromaffin cells from WT (a) or Cav1.3−/− mice (b) labeled with antibodies against Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3 and Cav1.4 channels (dilution 1 : 200) and the corresponding secondary antibody (dilution 1 : 200) Alexa Fluor excited at a wavelength of 594 nm (dilution 1 : 200). Experiments were performed on four paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. Calibration bar: 75 microns.

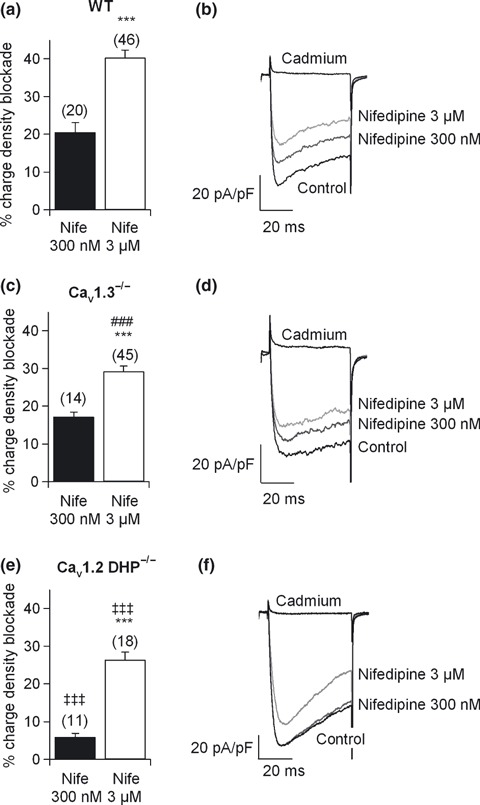

Sensitivity to DHPs of Cav1 channel subtypes

To further investigate the nature of Cav1 channels in mouse chromaffin cells, 300 nM nifedipine was tested on chromaffin cells from WT, Cav1.3−/− and Cav1.2DHP−/− mice. This DHP concentration should substantially inhibit Cav1.2 but not Cav1.3 currents (Koschak et al. 2001; Xu and Lipscombe 2001).

First, a ramp voltage protocol was performed to search for the peak current voltage (0–10 mV). Then, step‐depolarizing pulses of 50 ms to that voltage were applied every minute, from a V h of −80 mV. In WT cells, 300 nM nifedipine blocked the Ca2+ charge density by 21.7 ± 2% in 20 cells (Fig. 2a, black column; Fig. 2b, original traces) and by a similar amount (17 ± 1%, n = 14) in Cav1.3−/− cells (Fig. 2c, black column; Fig. 2d, original traces). This blockade must be selective for Cav1.2 channels, as shown by the identical blockade of 300 nM nifedipine in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. Accordingly, inhibition was almost absent in Cav1.2DHP−/− cells (6 ± 1%, n = 11; Fig. 2e, black column; Fig. 2f, original traces). These data indicate that Cav1.2 channels are expressed in mouse chromaffin cells.

Figure 2.

Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells. Sensitivity of Cav1 channel subtypes to DHPs. Square‐step depolarizing pulses of 50 ms duration were applied every 30 s to the peak current voltage. (a, c and e) Ca2+ charge density blockade obtained after perfusion with 300 nM (black columns) and 3 μM (white columns) nifedipine (Nife) in WT, Cav1.3−/− and Cav1.2DHP−/− cells, respectively. A large fraction of Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 21) did not respond to 300 nM nifedipine. (b, d and f) Original Ca2+ current traces under control conditions or after perfusion with 300 nM or 3 μM nifedipine in WT, Cav1.3−/− and Cav1.2DHP−/− cells, respectively. Experiments were performed on seven paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells and five paired cultures of WT and Cav1.2DHP−/− cells, using two mice from each strain. Numbers of cells indicated in parentheses. Bars represent means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, versus the percentage of the other concentration in the same mouse strain. ### p < 0.001, differences between WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. ‡‡‡ p < 0.001, differences between WT and Cav1.2DHP−/− cells.

Using the above protocol, 3 μM nifedipine blocked the Ca2+ charge density by 40 ± 2% in WT cells (n = 46), and by 29 ± 1.4% (n = 45) in Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively, indicating significant differences with respect to WT cells (Fig. 2a and c, white columns; Fig. 2b and d, original traces). Accordingly, at least 11% of the total Ca2+ charge density at the peak current voltage comes from the Cav1.3 channel. Inhibition was 26.4 ± 2% (n = 18) in cells from Cav1.2DHP−/− mice, which must be the outcome of Cav1.3 blockade together with the residual inhibition of mutated Cav1.2 (Sinnegger‐Brauns et al. 2004).

Significant differences were also noted in the amount of Ca2+ charge density inhibited by 3 μM nifedipine in Cav1.3−/− cells, 29 ± 1.4% (n = 45), with respect to that blocked by 300 nM nifedipine (Fig. 2c, white column; Fig. 2d, original traces). This indicates that 300 nM of the DHP blocked 60% of the total Cav1.2 channels present in mouse chromaffin cells (in good agreement with the DHP sensitivity of these channels reported in heterologous systems, Koschak et al. 2001; Xu and Lipscombe 2001).

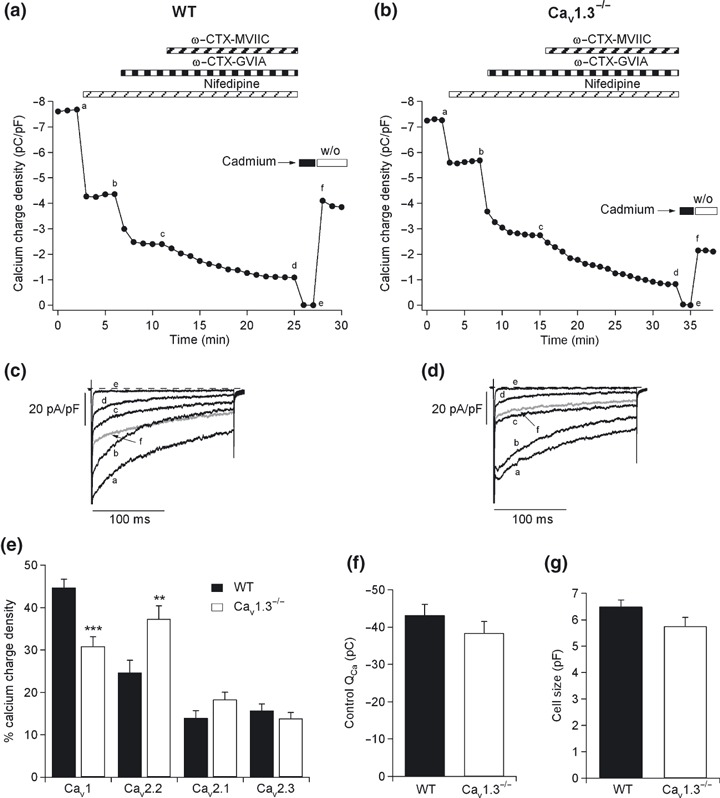

Cav1.3 channel deletion is offset by the increased expression of Cav2.2 channels

To examine if Cav1.3 channel deletion was counterbalanced by the increased expression of other Ca2+ channel types, cells were perfused with the DHP nifedipine at a concentration of 3 μM after control currents reached the steady‐state in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. The time course of a typical recording of the charge density blockade exerted by nifedipine in WT mice is shown in Fig. 3(a). Square‐step depolarizing pulses of 200‐ms duration at the peak current voltage were applied every 1 min. After 4 min of perfusion with nifedipine, other Ca2+ channel blockers were added sequentially and cumulatively to abolish the current carried by the non‐Cav1 channels: 1 μM ω‐CTX‐GVIA was applied for 5 min to block Cav2.2 channels, and 3 μM ω‐CTX‐MVIIC was added to the above Ca2+ channel blockers for 14 min, to further eliminate Cav2.1 channels. Finally, 200 μM CdCl2 was applied to abolish the current resistant to blockade by the above Ca2+ channel blockers. The original traces recorded in the presence of the different blockers are shown in Fig. 3(c). The contributions of the different Ca2+ channel types are shown in Fig. 3(e).

Figure 3.

Cav1 channel deletion compensated by the increased expression of other Cav channel types. Pharmacological dissection of Ca2+ channels in mouse chromaffin cells from WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. (a and b) Time course of the Ca2+ charge density obtained after sequentially and cumulatively adding the different Ca2+ channel blockers, in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively: 3 μM nifedipine was used to block Cav1 channels, 1 μM ω‐CTX‐GVIA to block Cav2.2 channels, 3 μM ω‐CTX‐MVIIC to block Cav2.1 channels, and 200 μM Cd2+ to block the residual Ca2+ current. (c and d) Original traces of the Ca2+ currents recorded at the stationary stage using each Ca2+ channel blocker (corresponding to points a–f in panels 3a and b, where a: control, b: after 3 μM nifedipine perfusion, c: after 3 μM nifedipine and 1 μM ω‐CTX‐GVIA perfusion and d: after 3 μM nifedipine, ω‐CTX‐GVIA and 3 μM ω‐CTX‐MVIIC perfusion). (e) Ca2+ charge density of the different Ca2+ channel types for WT (black columns) and Cav1.3−/− cells (white columns), respectively. (f) Total Ca2+ charge obtained under control conditions for WT (black column) and Cav1.3−/− cells (white column). (g) Sizes of chromaffin cells obtained from WT (black column) and Cav1.3−/− mice (white column). Experiments were performed on nine paired cultures of WT (n = 18 cells) and Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 17 cells), using 1–2 mice of each strain. Bars represent means ± SEM. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, versus the percentage of the same channel in the other mouse strain.

A similar protocol was conducted in the chromaffin cells of Cav1.3−/− mice (Fig. 3b and d). The contributions of the Ca2+ channel types in these knockout mice are displayed in Fig. 3(e). Significant differences between WT and Cav1.3−/− cells emerged in terms of Cav1 and Cav2.2 channel contributions. These data indicated that the absence of the Cav1.3α1 subunit was offset by a parallel increase in the expression of the Cav2.2 α1 subunit. No change was produced in the total charge (43.5 ± 2.5 pC and 38 ± 3 pC in the WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively) (Fig. 3f), or cell size between WT and Cav1.3−/− cells (6.5 ± 0.3 pF and 5.7 ± 0.4 pF for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively) (Fig. 3g).

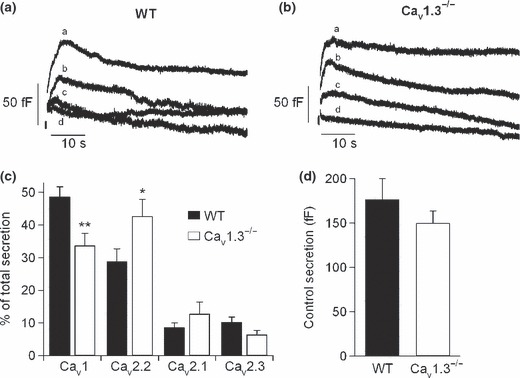

The exocytosis of vesicles was monitored by measuring C m, which was obtained simultaneously to the Ca2+ current recordings. Thus, the C m traces in Fig. 4(a and b) were obtained in the same cells as those in Fig. 3(a and b). The percentage total contribution to secretion of the Ca2+ channel types in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells is shown in Fig. 4(c). The reduction in the contribution of Cav1 channels to the secretory process paralleled the increased participation of Cav2.2 channels. As a result, the total secretion elicited by 200‐ms square‐step depolarizing pulses was not modified (179 ± 30 fF and 148 ± 15 fF in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively) (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Cav1 channel deletion compensated by the increased expression of other Ca2+ channel types. Contribution of Cav channels to the exocytosis of neurotransmitters in mouse chromaffin cells from WT and Cav1.3−/− mice. (a and b) C m traces recorded simultaneously to the Ca2+ currents of Fig. 2(c and d) in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. (c) Percentage of total secretion attributed to each Ca2+ channel type in WT (black columns) and Cav1.3−/− cells (white columns). (d) Total secretion attained under control conditions for WT (black column) and Cav1.3−/− cells (white column). Experiments were performed on seven paired cultures of WT (n = 15 cells) and Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 11 cells), using 1–2 mice from each strain. Bars represent means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, versus the percentage of the same channel in the other mouse strain.

Cav1.3 channels are activated at more negative membrane potentials than Cav1.2 channels

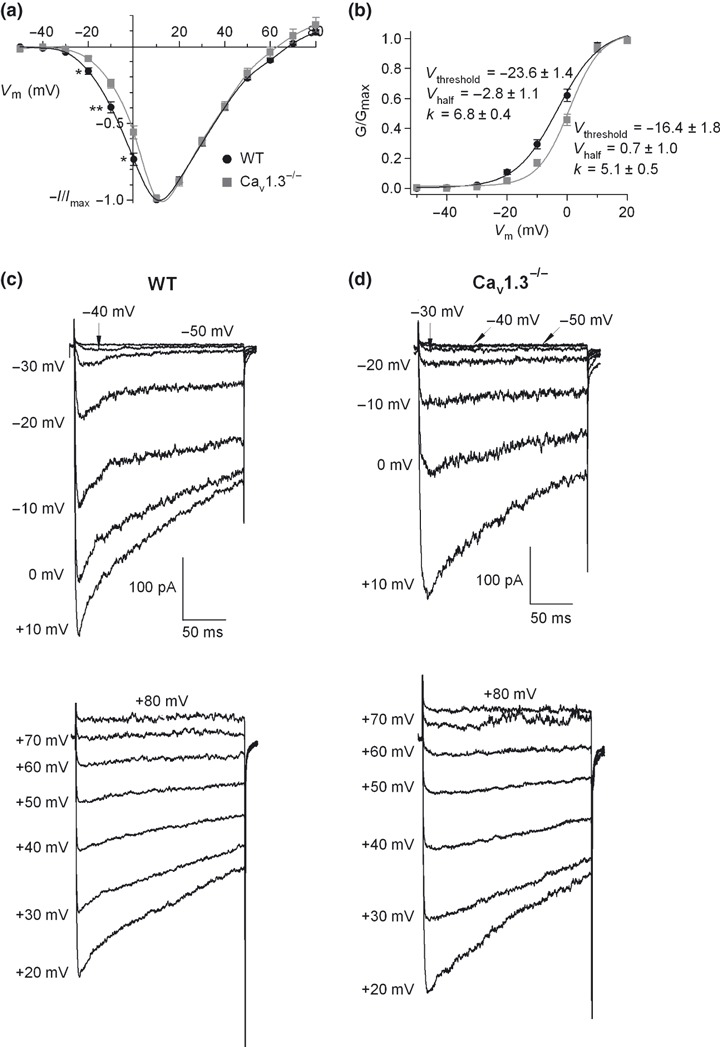

Ca2+ current versus voltage (I–V) curves were obtained by applying 200‐ms square‐step depolarizations at increasing potentials of 10 mV, from −50 mV to +80 mV, every 1 min (V h = −80 mV). Figure 5(a) displays the I–V curves for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively, obtained under control conditions. A clear rightward shift of the Cav1.3−/− I–V curve with respect to the WT I–V curve was obtained. Significant differences could be observed between the peak Ca2+ current at −20 mV,−10 mV and 0 mV in WT versus Cav1.3−/− mice. The fitting averages of both I–V curves to Boltzmann functions (eqn 1, see Material and Methods) yielded values of V threshold, V half and k for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells that differed significantly (Fig. 5b). Original recordings of Ca2+ currents recorded for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells are shown in Fig. 5(c and d), respectively.

Figure 5.

Voltage dependent activation of Ca2+ channels. (a) I–V curves obtained under control conditions in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 8–12). 200 ms square‐step depolarizing pulses at increasing potentials (voltage increments of 10 mV), from −50 mV to 80 mV, were applied every 1 min. Data were obtained from four paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using 1–2 mice from each strain and normalized as the percentage of current in control conditions at 10 mV, plotted as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (b) Averaged and superimposed smooth‐curve Boltzmann fittings obtained from the peak current‐voltage relations in panel a, plotted for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. (c and d) Original recordings of Ca2+ currents obtained under control conditions for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively, at the different voltages.

Cav1.2 channels are inactivated faster than Cav1.3 channels

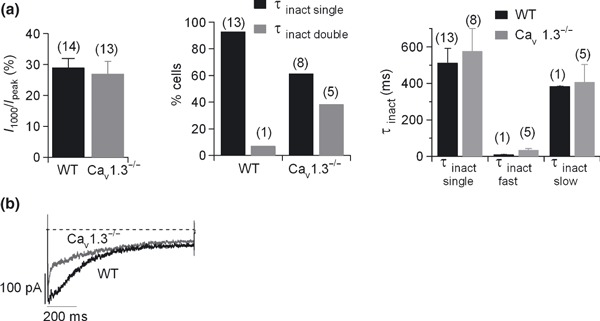

To explore possible differences in the inactivation processes, we applied long pulses of 1‐s duration. Currents were fitted to a double exponential function when they could not be well adjusted to a single exponential function.

Inactivation was determined as the Ca2+ current remaining at the end of the 1000 ms pulse expressed as a percentage of the peak current (I 1000/I peak) (Fig. 6a, left panel). Values were 29 ± 3% and 27 ± 4% for WT (n = 14) and Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 13, no significant differences), indicating that inactivation (around 70%) was incomplete at the end of a 1‐s depolarizing pulse.

Figure 6.

Kinetics of the Cav1 channel subtypes. One‐second square‐step depolarizing pulses were applied at −10 mV every 5 min. (a) Inactivation kinetics. Left, Ca2+ current remaining at the end of a 1‐s pulse expressed as a percentage of the peak current (I 1000/I peak) in WT (black column) and Cav1.3−/− cells (grey column); middle, percentage of cells whose inactivation kinetics could be well fitted to a single (τinact single, black columns) or to a double (τinact double, grey columns) exponential function in WT and Cav1.3−/−; right, the average τinact single yielded by the single exponential fitting, and τinact double, which exhibited two components, a fast component (τinact fast) and a slow component (τinact slow), were plotted for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells (black and grey columns, respectively). (b) Original traces of the Cav1 channel currents recorded in WT and Cav1.3−/−cells were averaged, superimposed and scaled to the peak WT Cav1 channel current. Number of cells indicated in parentheses. Data were obtained in three paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using two mice of each strain.

The inactivation time course during 1‐s depolarizations was mono‐ or biexponential. Biexponential inactivation was rarely seen in WT cells (7% cells, 1 cell out of 14), but frequently in Cav1.3−/− cells (5 out of 13 cells) (Fig. 6a, middle panel). Inactivation time constants obtained by single exponential fitting (τinact single) were identical in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. Inactivation time constants calculated from the double exponential curve fitting (τinact double), comprising a fast (τinact fast) and slow component (τinact slow), failed to vary significantly in the WT and Cav1.3−/− cells (Fig. 6a, right panel) (Table 1). Thus, most of the Cav1 currents in WT cells exhibited a single exponential inactivation fit, while currents in a subpopulation of Cav1 channels in Cav1.3−/− cells were fitted to a double exponential inactivation curve, revealing a fast component of inactivation.

Table 1.

Inactivation kinetics of Cav1 currents in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells

| I 1000/I peak (%) | τinact single (% cells) | τinact single (ms) | τinact double (% cells) | τinact fast (ms) | τinact slow (ms) | Contribution | Number of cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τinact fast (%) | τinact slow (%) | ||||||||

| WT | 29 ± 3 | 93 | 513 ± 78 | 7 | 10 | 385 | 45.5 | 54.4 | 14 |

| Cav1.3−/− | 27 ± 4 | 61.5 | 575 ± 125 | 38.5 | 35 ± 8 | 407 ± 96 | 42 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 | 13 |

Square‐step depolarizing pulses of 1‐s duration were applied at −10 mV from the V h. The following kinetic parameters were calculated for both strains of mice: I 1000/I peak: Ca2+ current remaining at the end of the 1‐s pulse expressed as a percentage of the peak current; τinact single: time constant of inactivation, obtained from the single exponential curve fitting; τinact double: time constant of inactivation, calculated from the double exponential curve fitting; τinact fast: fast component time constant of inactivation, obtained from the double exponential curve fitting; τinact slow: slow component time constant of inactivation, calculated from the double exponential curve fitting.

In Fig. 6(b), Cav1 currents calculated for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells were averaged, superimposed and scaled to the peak WT Cav1 channel current for comparison. Here, the WT Cav1 channel current was fitted to a single exponential curve (τinact = 233 ms), while the Cav1.3−/− channel current could be well fitted to a double exponential function (τinact fast = 8.8 ms; τinact slow = 416 ms). Thus, Cav1.2 channels are on average inactivated faster than Cav1.3 channels.

Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channel subtypes are functionally coupled to BK channels

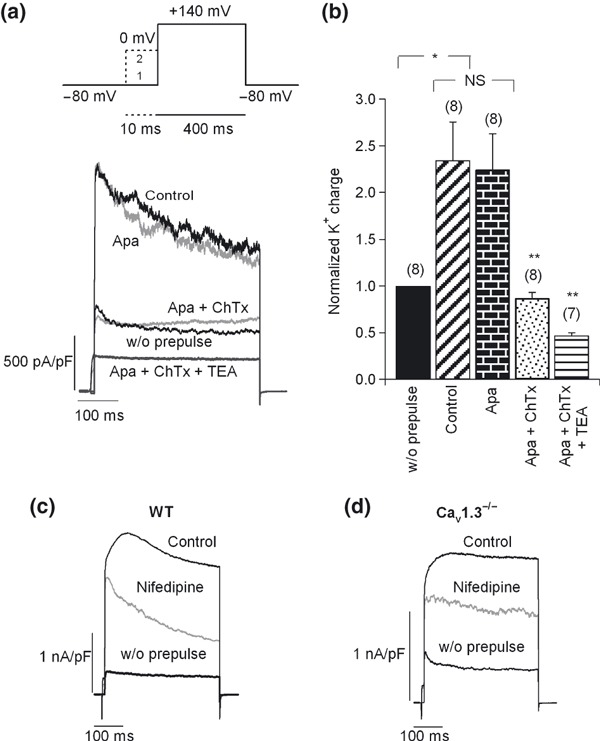

The coupling of Cav1 channels to BK channels was first reported in rat chromaffin cells by Prakriya and Lingle (1999). We were interested in determining the contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to cell excitability by studying the coupling of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels to BK channels. To recruit BK channels, short pre‐pulses of 10 ms were applied at 0 mV before a 400 ms test pulse (V t) to 140 mV or 180 mV; at these potentials, Ca2+ did not occur during the pulse. To check that Ca2+ entered exclusively during the pre‐pulse, a pulse not preceded by the pre‐pulse, which should evoke no secretion (reflected in the simultaneous C m measurement, data not shown), was first applied (Fig. 7a, upper part).

Figure 7.

Coupling of Cav1 channel subtypes to BK channels. (a) Upper section: double‐pulse protocol used to recruit BK channels. This included a 400 ms test pulse (V t) to 140 mV or above that potential (trace 1), followed by a 10‐ms pre‐pulse applied at 0 mV before V t (trace 2). The Ca2+ dependent K+ currents activated using this protocol were BK channels. Lower section: original K+ current traces recorded using the above protocol under control conditions and after perfusion with different K+ channel blockers, added sequentially and cumulatively: first, 200 nM apamin, 100 nM charibdotoxin (ChTx), and finally 45 mM TEA. Pulses were applied every 2 min. Numbers of cells are indicated in parentheses. (b) The K+ charge density was averaged and normalized for each condition with respect to the current in the absence of a pre‐pulse. (c–d) Effects of 3 μM nifedipine on BK channel currents in WT (c) and Cav1.3−/− cells (d). Number of cells: 14 WT cells, 11 Cav1.3−/− cells. Data were obtained in four paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using two mice of each strain.

The potentiation of K+ charge densities elicited by the pre‐pulse was identical in both strains of mice, and amounted to 268.7 ± 25% and 250 ± 20% in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. The Ca2+ dependent K+ currents activated using this protocol were BK channels, as shown by their insensitivity to 200 nM apamin (blockade of 1.55 ± 1% in five cells, only 11% in one cell), and their subsequent inhibition by 100 nM charybdotoxin (full inhibition in six out of six cells), that returned the current to the same level as the one elicited without a pre‐pulse or after perfusion with CdCl2 (200 μM) at the end of the experiment. Subsequent perfusion with tetraethylammonium (TEA, 45 mM) caused blockade of the total K+ charge density of 82 ± 2.5% (n = 6). BK currents represented 60.5 ± 3.9% (n = 16) of the total K+ current, and 80 ± 2% (n = 5) of the TEA‐sensitive K+ current. The original traces of the currents elicited in the stationary state under each condition in a typical cell are shown in the lower part of Fig. 7(a). Bar charts of normalized and averaged K+ charge densities with respect to the current in the absence of a pre‐pulse are provided in Fig. 7(b).

The effect of 3 μM nifedipine on the BK channels recruited using the aforementioned protocol was examined in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. Typical recordings of the action of this DHP in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells are shown in Fig. 7(c and d), respectively. In WT cells, the DHP blocked the BK channels by 52.7 ± 7%, while in Cav1.3−/− cells, these were blocked by 35 ± 4.6%. These data indicate that, although both channel subtypes are coupled to BK channels, the contribution of Cav1.2 channels to the recruitment of BK channels is greater than that of the Cav1.3 channel subtype.

Mainly Cav1.2 channels control action potential firing

The action potentials elicited by acetylcholine in chromaffin cells are known to be both Na+‐ (Biales et al. 1976) and Ca2+‐dependent (Brandt et al. 1976; Kidokoro et al., 1982; Kidokoro and Ritchie, 1980).

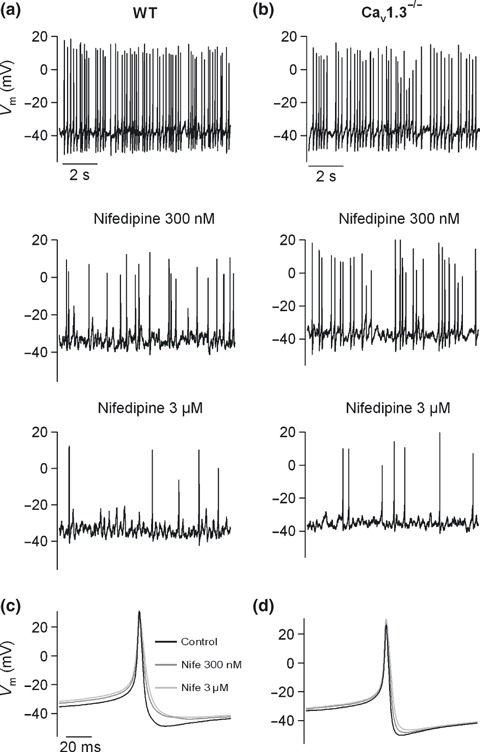

Cav1 channels have been assigned the role of firing spontaneous action potentials in mouse chromaffin cells by contributing to the inward pacemaker current underlying the action potential (Marcantoni et al. 2009). Spontaneous action potential firing would trigger basal neurotransmitter release (Zhou and Misler, 1995). Thus, we investigated the possible contribution of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels to firing and/or shaping action potentials in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, by measuring, in the current clamp configuration, the effects of nifedipine on the spontaneous firing of action potentials in cells of both strains of mice.

We observed spontaneous action potential firing in 62% WT cells (13 out of 21 cells tested), and in 59% Cav1.3−/− cells (10 out of 17 cells tested). These cells showed large Na+ currents (peak current at the ramp outset: 596 ± 207 pA in WT cells; 662 ± 204 pA in Cav1.3−/− cells), while cells not showing spontaneous activity exhibited small Na+ currents (23 ± 8 pA in WT cells; 41.7 ± 11 pA in Cav1.3−/− cells). Action potential frequencies of spontaneous firing were 3.9 ± 0.7 Hz and 2.5 ± 0.7 Hz for WT (n = 13) and Cav1.3−/− (n = 10) cells, respectively, showing no significant differences. This indicates no relevant contribution of Cav1.3 channels to firing.

The different characteristics of the action potentials in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells were analyzed before and after perfusion of the DHP in WT (Fig. 8a) and Cav1.3−/− (Fig. 8b): depolarization rate, overshoot potential, undershoot potential, height, half‐height width, depolarization rate and firing rate (Table 2). Nifedipine was initially tested at a concentration of 300 nM to selectively target Cav1.2 channels, and then a 3 μM concentration of the DHP was added to fully inhibit Cav1.2 and most Cav1.3 channels in WT cells. By averaging the action potentials recorded over 10 s in six WT cells and four Cav1.3−/− cells, mean action potentials under each condition were obtained (Fig. 8c and d). In WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, both concentrations of nifedipine significantly increased the half‐height width, yet decreased the undershoot, the rate of depolarization, and the firing frequency. These changes in the shape and frequency of firing of the action potential were identical in both strains of mice, and could be explained by BK channel blockade subsequent to the inhibition mainly of Cav1.2 channels (see Discussion).

Figure 8.

Contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to pacemaking activity, and shaping of action potential waveform. (a–b) Recordings of the spontaneous firing of action potentials performed in the current clamp configuration in WT (a) or Cav1.3−/− cells (b) under control conditions, and after perfusion with 300 nM nifedipine and 3 μM nifedipine. (c–d) Mean action potential obtained by averaging the action potentials recorded over 10 s under control conditions or after 300 nM and 3 μM nifedipine application to WT (n = 6) (c) or Cav1.3−/− cells (n = 4) (d). Data were obtained in two paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using 1–2 mice of each strain.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of the spontaneous action potentials yielded under control conditions or in the presence of 300 nM or 3 μM nifedipine in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells

| Depol. rate (V/s) | Overshoot (mV) | HH Width (ms) | Height (mV) | Undershoot (mV) | Repol. rate (V/s) | Firing rate (Hz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n = 6) | |||||||

| Control | 50.7 ± 10.9 | 31.0 ± 5.69 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 81.4 ± 5.8 | −50.5 ± 2.9 | −29.1 ± 4.4 | 4.9 ± 0.9 |

| Nife 300 nM | 38.6 ± 11.2 | 31.0 ± 4.0 | 5.4 ± 1.2* | 72.9 ± 8.2 | −45.7 ± 3.8* | −18.9 ± 4.5* | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

| Nife 3 μM | 39.2 ± 13.2 | 29.4 ± 5.0 | 5.8 ± 1.2* | 73.2 ± 7.4 | −43.8 ± 3.7*** | −15.9 ± 3.9* | 1.6 ± 0.5** |

| Cav1.3−/− (n = 4) | |||||||

| Control | 46.6 ± 18.7 | 26.3 ± 7.9 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 76.6 ± 10.5 | −50.4 ± 3.6 | −33.0 ± 5.5 | 4.5 ± 1.0 |

| Nife 300 nM | 40.3 ± 12.4 | 28.2 ± 6.6 | 3.8 ± 0.6* | 76.5 ± 9.0 | −48.3 ± 3.8*** | −26.5 ± 5.7# | 3.1 ± 0.8* |

| Nife 3 μM | 36.7 ± 8.2 | 29.0 ± 5.3 | 4.2 ± 0.5* | 75.2 ± 7.6 | −46.2 ± 3.9* | −20.6 ± 40.2*** | 1.2 ± 0.6* |

A spike was considered an action potential when the peak exceeded +10 mV. Data were obtained in two paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using 1–2 mice of each strain. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005; # p < 0.001. No statistically significant differences were detected in the different parameters between WT and Cav1.3−/− cells.

Depol. rate: maximal depolarization rate; Overshoot: maximal potential; HH Width: half‐height width; Height: total amplitude; Undershoot: minimal potential; Repol. rate: maximal repolarisation rate; Firing rate: frequency of firing.

These data also suggest that the blockade exerted by 300 nM nifedipine on Cav1.2 channels is incomplete at −40 mV (interspike potential). Thus, the higher frequency of firing in WT or Cav1.3−/− cells in the presence of nifedipine 300 nM with respect to that observed in the presence of 3 μM nifedipine, indicates that partial and complete blockade of Cav1.2 channels, respectively, and consequently of BK channels, occurs under both conditions.

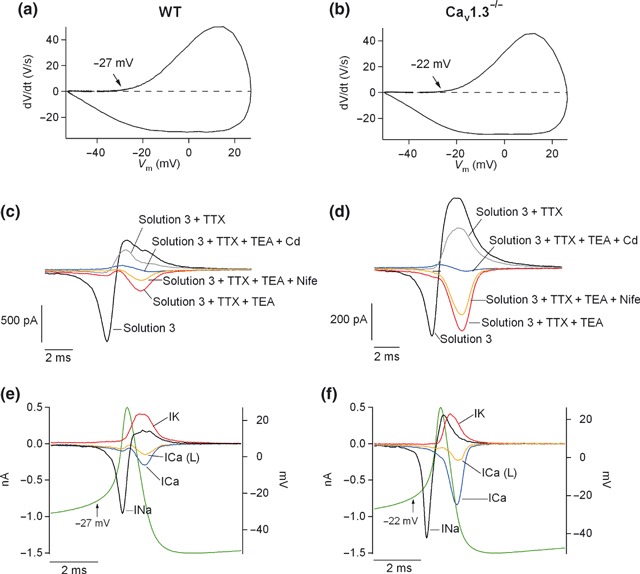

The identical number of cells showing spontaneous firing and the similar firing frequency of WT cells when compared to Cav1.3−/− cells is sufficient argument against a major role of Cav1.3 channels in action potential firing. However, to further investigate this issue, additional experiments were performed. First, the contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to the inward current preceding the action potential was addressed. We constructed a phase‐plane plot to identify the threshold potential for each mouse strain (Jenerick 1963) (Fig. 9a and b). The voltage stimuli applied were the mean action potentials obtained in Fig. 8(c and d) under control conditions for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. The threshold potential was then calculated as the voltage at which dV/dt increased from the initial baseline (marked by the arrows). The spike thresholds obtained were −27 mV and −22 mV for WT and Ca1.3−/− cells, respectively.

Figure 9.

Contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to pacemaking activity. (a–b) Phase‐plane plot obtained by plotting dV/dt versus the voltage stimulus in WT and Cav1.3−/−, respectively. Arrows indicate the points at which dV/dt increased from the initial baseline (threshold potential). Estimated threshold potentials were −27 mV and −22 mV for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively; (c–d) action potential clamp experiments were performed by applying the mean voltage stimulus obtained under control conditions in Fig. 8(g and h) every 30 s. Starting from ‘Solution 3’ (see Material and Methods), different blockers were sequentially added to that solution: 2 μM TTX (Solution 3 + TTX), 45 mM TEA (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA), 3 μM nifedipine (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA + Nife) and 200 μM CdCl2 (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA + Nife + Cd). Perfusion with each solution was continued for at least 2 min so that the currents reached the steady‐state. Number of cell: 22 WT cells, 25 Cav1.3−/− cells. Data were obtained in four paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using two mice of each strain. (e–f) Ion currents were calculated from the recordings of panels (c) and (d), for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. To obtain the Na+ current, the current obtained after perfusion with ‘Solution 3 + TTX’ was subtracted from the ‘Solution 3’ current. The K+ current was calculated as the difference in the current yielded under ‘Solution 3 + TTX + TEA’ minus ‘Solution 3 + TTX’. The Cav1 current was obtained as the difference between ‘Solution 3 + TTX + TEA’ and ‘Solution 3 + TTX + TEA + Nife’ and the total Ca2+ current as the difference between ‘Solution 3 + TTX + TEA’ and ‘Solution 3 + TTX + TEA + Cd’. The voltage stimulus, obtained from Fig. 8(g and h), control conditions, was superimposed on the ion currents. Data were obtained in 4 paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using two mice of each strain.

To elucidate the contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to the inward pacemaker current, we assessed the ionic components of this current, taken as the current flowing before the threshold potential was reached in action potential clamp experiments. Na+, K+ and Ca2+ blockers were added sequentially and cumulatively to dissect the contributions of the different ion conductances underlying the action potential in mouse chromaffin cells. Thus, cells were initially perfused with a control solution (Solution 3), then 2 μM TTX was added (Solution 3 + TTX) to block Na+ channels, followed by 45 mM TEA (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA) to block K+ channels. Next, 3 μM nifedipine was included in the perfusion solution (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA + Nife), and finally, 200 μM CdCl2 (Solution 3 + TTX + TEA−Cd) (Fig. 9c and d). From these recordings, Na+, K+, Cav1 and total Ca2+ currents were calculated (see legend to Fig. 9), and presented in Fig. 9(e and f).

Cells were sorted in two groups according to the Cav1 channel contribution at the calculated threshold potentials, inferred from the Cav1 current trace (boundary: 10 pA of Cav1 current). In one group of cells (data not shown), Cav1 channel contributions to the Ca2+ current (< 10 pA) were −1.9 ± 1.2 pA (n = 13) and −1.6 ± 1.6 pA (n = 13) at the threshold potential for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively. Total Ca2+ currents amounted to −4.2 ± 1.9 pA (n = 12) and −4.1 ± 1.5 pA (n = 13). Hence, Cav1 channels are not likely to contribute to the firing of action potentials in this set of cells, as the range of current injection because of these channels evokes potential increases of 0.4–4.4 mV in WT and 0.41–1.88 mV in Cav1.3−/− cells (taking as R in 4 ± 0.5 GΩ and 4.1 ± 0.3 GΩ, for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively).

In the other group of cells (Cav1 current at the threshold potential > 10 pA) (Fig. 9c–f), Cav1 channel contributions to the Ca2+ current were −36.1 ± 6.7 pA (n = 10) and −19 ± 3.2 pA (n = 12) at the threshold potential (p < 0.05), for WT and Ca1.3−/− cells, respectively. The total Ca2+ current was −44.5 ± 9 pA (n = 10) for WT cells and −29.7 ± 3.9 pA (n = 12) for Cav1.3−/− cells (no significant difference). This means that the contributions of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels to the total Ca2+ current at the threshold potential were 64% and 17%, respectively. Thus, in about half the cells, Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels contributed to the inward current that precedes the threshold potential, with a much greater participation of Cav1.2 than Cav1.3 channels.

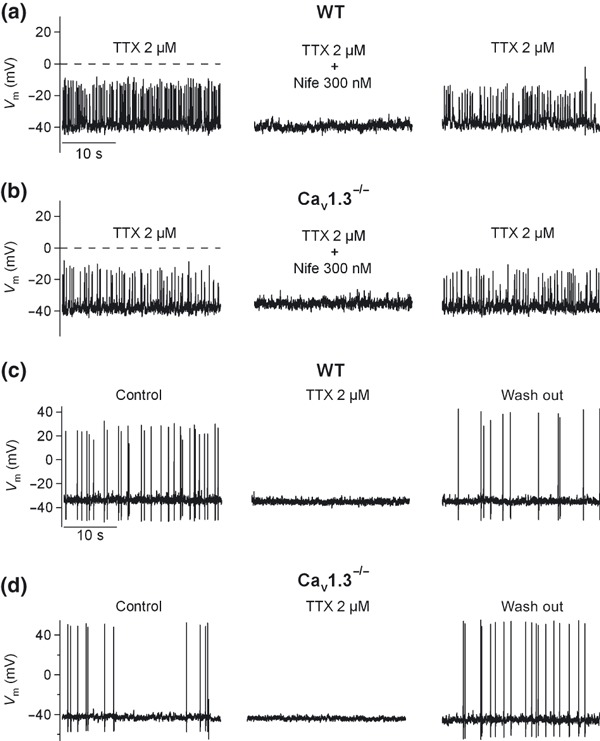

Further confirmation of Cav1.2 channel as a major contributor to firing was obtained in a second set of experiments whereby, in the presence of 2 μM TTX, spontaneous oscillatory activity was observed, even in Cav1.3−/− cells. This activity was completely abolished after perfusion with 300 nM nifedipine (in four out of eight WT cells and three out of six Cav1.3−/− cells) (Fig. 10a and b). In the rest of the cells, firing was triggered exclusively by Na+ channels. Full blockade of spontaneous firing by TTX was observed in four out of eight WT cells and in three out of six Cav1.3−/− cells (Fig. 10c and d).

Figure 10.

Contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to pacemaking activity. (a–b) In a different set of experiments performed under the current‐clamp configuration, the spontaneous oscillatory activity resistant to TTX, obtained in half the cells treated with this toxin, was reversibly abolished by 300 nM nifedipine in WT (a) or Cav1.3−/− cells (b). In the other half of the cells, reversible blockade of spontaneous action potentials by 2 μM TTX in WT (c) or Cav1.3−/− (d) cells was achieved. Data were obtained in two paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells using two mice of each strain.

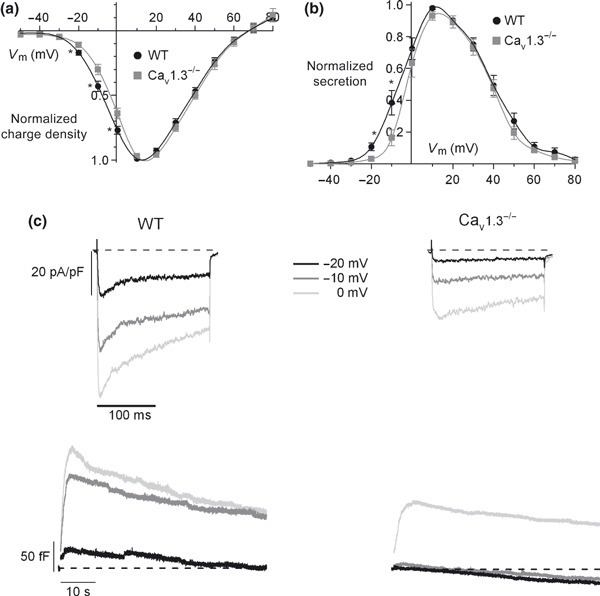

Cav1.3 channels are major contributors to the Ca2+ charge and chromaffin vesicle exocytosis at negative membrane potentials, while Cav1.2 channels contribute at more positive potentials

Cell membrane capacitance traces simultaneous to Ca2+ were recorded in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells during the I–V protocol mentioned in Fig. 5. The corresponding exocytosis (calculated as the increase in C m) elicited under control conditions in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells at the different voltages was calculated and plotted in Fig. 11(b). The contribution to the exocytotic process of Cav1.3 channels was 71.7% at −20 mV and 57.7% at −10 mV, while the contribution of these channels to the total charge density was only 35.3% and 30.2%, respectively (Fig. 11a). These data reflect a major role of Cav1.3 channels in controlling exocytosis at hyperpolarized membrane potentials. Original recordings of C m traces and Ca2+ current densities can be found in Fig. 11(c). Above −10 mV, exocytosis control by Cav1 channel subtypes is restricted to Cav1.2 channels, as reflected in the overlapping I–V curves (Fig. 11b).

Figure 11.

Contribution of Cav1 channel subtypes to the Ca2+ charge and exocytosis of chromaffin vesicles. Ca2+ charge density (a) and the corresponding exocytosis (b) versus the voltage in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. Data were obtained in the same experiments as in Fig. 3 (n = 8–12, from four paired cultures of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, using 1–2 mice of each strain) and normalized as the percentage of charge density in control conditions at 10 mV, plotted as the mean ± SEM. (c) Original traces of Ca2+ current density and the corresponding exocytosis elicited at −20 mV, −10 mV and 0 mV in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Previous reports have described the voltage dependence of activation or the kinetic properties of Cav1 channel isoforms in heterologous systems (Koschak et al. 2001; Xu and Lipscombe 2001) and even in some primary cell types (Mangoni et al. 2003; Olson et al. 2005), but as far as we are aware, our study provides the most complete characterization of relative Cav1.2/Cav1.3 channel function in a truly physiological native cell system.

Here, we conclude that Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels are the Cav1 channel subtypes expressed in mouse chromaffin cells. The evidence for this is that: (i) antibodies against Cav1.1α1, Cav1.2α1, Cav1.3α1 and Cav1.4α1 subunits only revealed the presence of Cav1.2α1 and Cav1.3α1 subunits; (ii) 3 μM nifedipine blockade of the Ca2+ charge density was reduced in Cav1.3−/− cells with respect to WT cells; and (iii) 300 nM nifedipine diminished the Ca2+ charge density by 21.7 ± 2% and 17.2 ± 1% in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, yet only by 6 ± 1% in chromaffin cells from transgenic mice lacking the high sensitivity of Cav1.2α1 subunits to DHPs, indicating non‐Cav1.3 channels were of the Cav1.2 subtype.

Cav1.3 channels were activated at more hyperpolarized membrane potentials than Cav1.2 channels. This was indicated by the rightward shift of the I–V curve recorded under control conditions in Cav1.3−/− cells with respect to that obtained in WT cells, yielding V threshold values of −23.6 ± 1.4 mV and −16.4 ± 1.8 mV (plus ‐21 mV to correct for the liquid junction potential) for WT and Cav1.3−/− Cav1 channel subtypes, respectively. This voltage difference was smaller than that reported in other cell systems, probably because of the low expression of Cav1.3 channels in mouse chromaffin cells. In sino‐atrial node cells, Mangoni et al. (2003) showed that Cav1 currents were activated at about −50 mV (WT cells) and −20 mV (Cav1.3−/− cells) in 1.8 mM Ca2+. In heterologous systems, using 15–20 mM Ba2+, the V threshold of activation for the Cav1.3 channels has been cited as −45.7 ± 0.5 mV, and −31.5 mV for Cav1.2 channels (Koschak et al. 2001). Xu and Lipscombe (2001) observed the onset of Cav1.3 channel activation at approximately −55 mV in 5 mM Ba2+ (or 2 mM Ca2+), while Cav1.2 channels became activated at −35 mV.

Cav1.2 channels were on average faster inactivated than Cav1.3 channels, an effect that could be unmasked in WT cells by the slower inactivated Cav1.3 channels. Expression in heterologous systems revealed differences in the inactivation behavior of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels. Because of a more pronounced Ca2+ dependent inactivation, Cav1.3 channels could be faster inactivated with Ca2+ as the charge carrier, but voltage‐dependent inactivation (recorded in Ba2+) appeared slower than in Cav1.2 channels (Koschak et al. 2001; Xu and Lipscombe 2001; Yang et al. 2006; Singh et al. 2008). In native systems, Cav1.3 channels showed strong Ca2+ dependent inactivation in the sinoatrial node and the endocrine pancreas (Plant 1988; Zhang et al. 2002; Mangoni et al. 2003), while in inner hair cells Ca2+ dependent inactivation was much weaker or absent (Platzer et al. 2000; Marcotti et al. 2003; Michna et al. 2003; Song et al. 2003). This might be because of the inhibition of Ca2+ dependent inactivation by Ca2+ binding proteins (for a review see Striessnig 2007). Co‐expression of Cav1.3α1 with syntaxin, vesicle‐associated membrane protein (VAMP) and synaptosomal‐associated protein (SNAP) also reduced the extent of Ca2+ current inactivation (Song et al. 2003). Our results might suggest that auxiliary subunits, or other channel associated proteins, could substantially condition the inactivation kinetics of Cav1 channels in the native system, and thus, give rise to differences with respect to channels expressed in heterologous systems.

The function of Cav1 channel subtypes was explored in relation to cell excitability and exocytosis. Regarding cell excitability, Cav1.2 channels were mainly functionally coupled to BK channels (53% and 35% of 3 μM nifedipine blockade of BK channels, respectively, in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells). This major coupling of Cav1.2 channels to BK channels is also reflected in the identical parameters of the action potentials obtained after nifedipine treatment (300 nM or 3 μM) in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells (Fig. 8, Table 2). Thus, the coupling between BK and Cav1.2 channels here observed would explain the change in the action potential waveform elicited by nifedipine, such that it slowed down the repolarisation stage of the action potential, with the consequent broadening of the spike (Fig. 8, Table 2).

This coupling would also explain, at least in part, the plasma membrane depolarization yielded by the DHP. It has been extensively shown that Ca2+ channel blockade often results in broadening of the action potential (Sah and McLachlan 1992; Shao et al. 1999; Faber and Sah 2002, 2003; Sun et al. 2003; Goldberg and Wilson 2005). Despite this being the opposite effect expected of blocking the entry of positively charged ions, it reflects powerful coupling to BK channels, so that the net effect is to inhibit a net outward current, that is, the K+ flux triggered by the Ca2+ entry outweighs the Ca2+ entry itself, as has been previously reported (Jackson et al. 2004). The depolarization caused by the DHP might affect other conductances with the consequence of reducing the firing frequency (Bean 2007). Thus, Cav1.2 channels model the shape of action potentials by coupling to BK channels.

Action potential firing was mainly controlled by Cav1.2 channels. This conclusion is supported by the following lines of evidence. First, the number of cells exhibiting spontaneous firing and the frequency of spontaneous action potential firing were similar for WT and Cav1.3−/− cells. Second, Cav1 channels represented 81% of the total Ca2+ current at the threshold potential in half the cells, with a major contribution of Cav1.2 channels (64% and 17% because of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, respectively). Third, spontaneous action potential firing was fully blocked by TTX in half the WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, or was driven by the toxin to an oscillatory activity in the other half of WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, showing that the absence of Cav1.3 channels did not prevent the cell from firing. And finally, the oscillatory activity was abolished by nifedipine in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, which reflects this activity was mediated through Cav1.2 channels. The oscillatory activity sensitive to DHP had also been described in dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons (Jackson et al. 2004) or in adult, but not juvenile, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Chan et al. 2007). This could therefore indicate that cells exhibiting Ca2+‐dependent firing might find themselves at a later developmental stage to those in which Ca2+ does not contribute to firing.

Strikingly, recent conclusions reported by Marcantoni et al. (2010) are contradictory to ours. These authors attributed a prominent role in spontaneous firing to Cav1.3 channels, despite the fact that the deletion of these channels did not affect the firing frequency. The major contribution of Cav1.3 with respect to Cav1.2 channels in spontaneous action potential firing was mainly supported by the reduction in the percentage of cells that showed spontaneous firing, 80% and 30% in WT and Cav1.3−/− cells, respectively.

The different results obtained by Marcantoni et al. could be explained by the fact that the mice used in both our and Marcantoni’s studies, obtained from the same source, were highly infected with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV). For the present study, these infected mice were bred under SPF conditions through a transfer process of embryos to uninfected mother mice. There is no mention made of a disinfection procedure in the Marcantoni et al. (2010) paper.

The E proteins of several coronaviruses, including MHV, are viroporins that exhibit ion channel activity (Liao et al. 2004; 2004, 2006; Madan et al. 2005). Viroporins are a large family of viral proteins able to enhance membrane permeability, promoting virus budding. Mammalian cells are also readily permeabilized by the expression of MHV E protein (Madan et al. 2005). They form cation‐selective ion channels in planar lipid bilayers, with a high selectivity for Na+ (Wilson et al. 2004). In addition, MHV infection induces an immediate and transient Ca2+ increase in DBT cells, a murine astrocytoma cell line. The Ca2+ increase is the result of the influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular medium through Cav1 channels, as it is sensitive to nifedipine and verapamil (Kraeft et al. 1997). This implies that Cav1 channels are affected by MHV infection. Thus, if the Na+ and Ca2+ channels involved in firing are in some way altered in MHV infected cells, action potential firing might also be influenced. Na+ and Ca2+ entry to the cytosol might depolarize and inactivate certain channels related to firing, Na+ channels or Cav1 channel subtypes. This would explain why the Cav1.3−/− mice in the study by Marcantoni and coworkers showed such a low percentage of spontaneously firing cells compared to their WT non‐infected counterparts.

Furthermore, cross‐talk between the immune system and the adrenal gland is well documented. For instance, there is increased catecholamine release by the adrenal medulla during periods of stress and infection (Zhou and Jones 1993). Further, cytokines stimulate the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis leading to augmented glucocorticoid production by the adrenal cortex (Turnbull and Rivier 1995; Buckingham et al. 1996). There are also direct paracrine interactions within the adrenal gland itself (Marx et al. 1998; Nussdorfer and Mazzocchi 1998), whereby cytokines are produced both by adrenal cells and by macrophages. Adrenal glands have a population of macrophages distributed throughout the cortex and medulla (Gonzalez‐Hernandez et al. 1994; Schober et al. 1998), some of which lie adjacent to the catecholamine producing chromaffin cells. Hence, in the particular case of MHV infection, this virus increases IL‐6 production through p39 MAPK activation in macrophage‐derived J774.1 cells (Banerjee et al. 2002). It is known that IL‐6 directly induces glucocorticoid production (Nussdorfer and Mazzocchi 1998; Willenberg et al. 2002), which increases adrenaline synthesis by stimulation of phenylethanolamine N‐methyltransferase activity (Wurtman and Axelrod 1966; Axelrod and Reisine 1984). Adrenaline is preferentially a β‐adrenergic agonist. β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors have been shown to modulate Cav1 channels in rat chromaffin cells (Cesetti et al. 2003). Therefore, MHV infection could also modify the paracrine modulation of Cav1 channel function through enhanced stress and elevated medullary catecholamine secretion.

Here, we also show that Cav1.3 channels play a major role in controlling the exocytotic process at hyperpolarized membrane potentials. The contribution of Cav1.3 channels to exocytosis at −20 mV and −10 mV was double their contribution to the charge density at those voltages. Above 0 mV, the control of exocytosis by Cav1 channels is restricted to Cav1.2 channel subtypes. Thus, Cav1 channel subtypes are able to fine tune exocytosis by operating at different voltage ranges.

In the present study, different roles are attributed to Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channel subtypes in spontaneous action potential firing and secretion of neurotransmitters at negative membrane potentials, respectively. In the sinoatrial node, Cav1.3 channels are the Cav1 channel subtypes that control pacemaker activity (Mangoni et al. 2003), but interestingly, Cav1.3 channels show strong Ca2+ dependent inactivation in those cells (Zhang et al. 2002; Mangoni et al. 2003). Similarly, in our study, Cav1.2 channels were the Cav1 channel subtypes that were most quickly inactivated, and consequently, they will contribute to the faster voltage dependent inactivation of Na+ channels. Na+ and Ca2+ channel inactivation are conditions required for subsequent initiation of Na+ and/or Ca2+ dependent action potentials to maintain repetitive firing. Finally, Cav1.3 channels are the Cav1 channel subtypes that mainly control secretion at negative potentials, as they contribute more to Ca2+ entry at those potentials, and consequently, to the Ca2+ dependent neurotransmitter secretory process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joerg Striessnig and Martina J. Sinnegger‐Brauns for providing the Cav1.3−/− and Cav1.2DHP−/− mice and Joerg Striessnig for discussion. AHV holds a fellowship from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología Nº. BFU2005‐00743/BFI and from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Nº. BFU2008‐01382 awarded to AA. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albillos A., Carbone E., Gandía L., García A. G. and Pollo A. (1996) Opioid inhibition of Ca2+ channel subtypes in bovine chromaffin cells: selectivity of action and voltage‐dependence. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 1561–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albillos A., Neher E. and Moser T. (2000) R‐type Ca2+ channels are coupled to the rapid component of secretion in mouse adrenal slice chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 20, 8323–8330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albillos A., Pérez‐Alvarez A. and Striessnig J. (2006) Pharmacological and electrophysiological characterization of Class D L‐type calcium channels in mouse chromaffin cells (abstract). Proceedings of 5th Forum of European Neuroscience, Vienna, Austria, p. 135.

- Aldea M., Jun K., Shin H. S., Andrés‐Mateos E., Solís‐Garrido L. M., Montiel C., García A. G. and Albillos A. (2002) A perforated patch‐clamp study of calcium currents and exocytosis in chromaffin cells of wild‐type and alpha (1A) knockout mice. J. Neurochem. 81, 911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod J. and Reisine T. D. (1984) Stress hormones: their interaction and regulation. Science 224, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Narayanan K., Mizutani T. and Makino S. (2002) Murine coronavirus replication‐induced p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation promotes interleukin‐6 production and virus replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 76, 5937–5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean B. P. (2007) The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 451–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biales B., Dichter M. and Tischler A. (1976) Electrical excitability of cultured adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 262, 743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt B. L., Hagiwara S., Kidokoro Y. and Miyazaki S. (1976) Action potentials in the rat chromaffin cell and effects of acetylcholine. J. Physiol. 263, 417–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt A., Striessnig J. and Moser T. (2003) Cav1.3 channels are essential for development and presynaptic activity of cochlear inner hair cells. J. Neurosci. 23, 10832–10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham J. C., Loxley H. D., Christian H. C. and Philip J. G. (1996) Activation of the HPA axis by immune insults: roles and interactions of cytokines, eicosanoids, glucocorticoids. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 54, 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli V., Hernández‐Guijo J. M., Baldelli P. and Carbone E. (2001) Direct autocrine inhibition and cAMP‐dependent potentiation of single L‐type Ca2+ channels in bovine chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 532, 73–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesetti T., Hernández‐Guijo J. M., Baldelli P., Carabelli V. and Carbone E. (2003) Opposite action of beta1‐ and beta2‐adrenergic receptors on Ca(V)1 L‐channel current in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 23, 73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. S., Guzman J. N., Ilijic E., Mercer J. N., Rick C., Tkatch T., Meredith G. E. and Surmeier D. J. (2007) ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature 447, 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber E. S. and Sah P. (2002) Physiological role of calcium‐activated potassium currents in the rat lateral amygdala. J. Neurosci. 22, 1618–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber E. S. and Sah P. (2003) Ca2+‐activated K+ (BK) channel inactivation contributes to spike broadening during repetitive firing in the rat lateral amygdala. J. Physiol. 552, 483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J. A. and Wilson C. J. (2005) Control of spontaneous firing patterns by the selective coupling of calcium currents to calcium‐activated potassium currents in striatal cholinergic interneurons. J. Neurosci. 25, 10230–10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez‐Hernandez J. A., Bornstein S. R., Ehrhart‐Bornstein M., Geschwend J. E., Adler G. and Scherbaum W. A. (1994) Macrophages within the human adrenal gland. Cell Tissue Res. 278, 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell J. W., Westenbroek R. E., Warner C., Ahlijanian M. K., Prystay W., Gilbert M. M., Snutch T. P. and Catterall W. A. (1993) Identification and differential subcellular localization of the neuronal class C and class D L‐type calcium channel alpha 1 subunits. J. Cell Biol. 123, 949–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. C., Yao G. L. and Bean B. P. (2004) Mechanism of spontaneous firing in dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 7985–7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerick H. (1963) Phase plane trajectories of the muscle spike potential. Biophys. J. 3, 363–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidokoro Y. and Ritchie A. K. (1980) Chromaffin cell action potentials and their possible role in adrenaline secretion from rat adrenal medulla. J. Physiol. 307, 199–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidokoro Y., Miyazaki S. and Ozawa S. (1982) Acetylcholine‐induced membrane depolarization and potential fluctuations in the rat adrenal chromaffin cell. J. Physiol. 324, 203–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschak A., Reimer D., Huber I., Grabner M., Glossmann H., Engel J. and Striessnig J. (2001) alpha 1D (Cav1.3) subunits can form l‐type Ca2+ channels activating at negative voltages. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 22100–22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeft S. K., Chen D. S., Li H. P., Chen L. B. and Lai M. M. (1997) Mouse hepatitis virus infection induces an early, transient calcium influx in mouse astrocytoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 237, 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Lescar J., Tam J. P. and Liu D. X. (2004) Expression of SARS coronavirus envelope protein in Escherichia coli cells alters membrane permeability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325, 374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López M. G., Villarroya M., Lara B., Martínez Sierra R., Albillos A., García A. G. and Gandía L. (1994) Q‐ and L‐type Ca2+ channels dominate the control of secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett. 349, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan V., Garcia M. J., Sanz M. A. and Carrasco L. (2005) Viroporin activity of murine hepatitis virus E protein. FEBS Lett. 579, 3607–3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni M. E., Couette B., Bourinet E., Platzer J., Reimer D., Striessnig J. and Nargeot J. (2003) Functional role of L‐type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5543–5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcantoni A., Carabelli V., Vandael D. H., Comunanza V. and Carbone E. (2009) PDE type‐4 inhibition increases L‐type Ca(2 + ) currents, action potential firing, and quantal size of exocytosis in mouse chromaffin cells. Pflugers Arch. 457, 1093–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcantoni A., Vandael D. H., Mahapatra S., Carabelli V., Sinnegger‐Brauns M. J., Striessnig J. and Carbone E. (2010) Loss of Cav1.3 channels reveals the critical role of L‐type and BK channel coupling in pacemaking mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 30, 491–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotti W., Johnson S. L., Rusch A. and Kros C. J. (2003) Sodium and calcium currents shape action potentials in immature mouse inner hair cells. J. Physiol. (Lond) 552, 743–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx C., Ehrhart‐Bornstein M., Scherbaum W. A. and Bornstein S. R. (1998) Regulation of adrenocortical function by cytokines‐relevance for immune‐endocrine interaction. Horm. Metab. Res. 30, 416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michna M., Knirsch M., Hoda J. C., Muenkner S., Langer P., Platzer J., Striessnig J. and Engel J. (2003) Cav1.3 (alpha1D) Ca2+ in neonatal outer hair cells of mice. J. Physiol. (Lond) 553, 747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser T. (1998) Low conductance intercellular coupling between mouse chromaffin cells in situ. J. Physiol. 506, 195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung Y., Skrypnyk N., Jeong M. J., Lee T., Lee M. S., Kim H. L., Chin H., Suh P. G., Kim S. S. and Shin H. S. (2001) Requirement for the L‐type Ca(2+) channel alpha(1D) subunit in postnatal pancreatic beta cell generation. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussdorfer G. G. and Mazzocchi G. (1998) Immune‐endocrine interactions in the mammalian adrenal gland: facts and hypotheses. Int. Rev. Cytol. 183, 143–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson P. A., Tkatch T., Hernandez‐Lopez S., Ulrich S., Ilijic E., Mugnaini E., Zhang H., Bezprozvanny I. and Surmeier D. J. (2005) G‐protein‐coupled receptor modulation of striatal CaV1.3 L‐type Ca2+ channels is dependent on a Shank‐binding domain. J. Neurosci. 25, 1050–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Alvarez A., Romacho T., Striessnig J. and Albillos A. (2006) Molecular and electrophysiological characterization of L‐type calcium channels in mouse chromaffin cells (abstract). Proceedings of 13th International Symposium on Chromaffin Cell Biology, Pucón, Chile, p. 73.

- Plant T. D. (1988) Properties and calcium‐dependent inactivation of calcium currents in cultured mouse pancreatic B‐cells. J. Physiol. (Lond) 404, 731–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platzer J., Engel J., Schrott‐Fischer A., Stephan K., Bova S., Chen H., Zheng H. and Striessnig J. (2000) Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L‐type Ca2+ channels. Cell 102, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo‐Parada L., Chan S. A. and Smith C. (2006) An activity‐dependent increased role for L‐type calcium channels in exocytosis is regulated by adrenergic signaling in chromaffin cells. Neuroscience 143, 445–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M. and Lingle C. J. (1999) BK channel activation by brief depolarizations requires Ca2+ influx through L‐ and Q‐type Ca2+ channels in rat chromaffin cells. J. Neurophysiol. 81, 2267–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P. and McLachlan E. M. (1992) Potassium currents contributing to action potential repolarization and the afterhyperpolarization in rat vagal motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 68, 1834–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A., Huber K., Fey J. and Unsicker K. (1998) Distinct populations of macrophages in the adult rat adrenal gland: a subpopulation with neurotrophin‐4‐like immunoreactivity. Cell Tissue Res. 291, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L. R., Halvorsrud R., Borg‐Graham L. and Storm J. F. (1999) The role of BK‐type Ca2+‐dependent K+ channels in spike broadening during repetitive firing in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Physiol. 521, 135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Gebhart M., Fritsch R., Sinnegger‐Brauns M. J., Poggiani C., Hoda J. C., Engel J., Romanin C., Striessnig J. and Koschak A. (2008) Modulation of voltage‐ and Ca2+‐dependent gating of CaV1.3 L‐type calcium channels by alternative splicing of a C‐terminal regulatory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20733–20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnegger‐Brauns M. J., Hetzenauer A., Huber I. G. et al. (2004) Isoform‐specific regulation of mood behavior and pancreatic beta cell and cardiovascular function by L‐type Ca2+ channels. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1382–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Nie L., Rodriguez‐Contreras A., Sheng Z. H. and Yamoah E. N. (2003) Functional interaction of auxiliary subunits and synaptic proteins with Ca(v)1.3 may impart hair cell Ca2+ current properties. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striessnig J. (2007) C‐terminal tailoring of L‐type calcium channel function. J. Physiol. 585, 643–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Gu X. Q. and Haddad G. G. (2003) Calcium influx via L‐ and N‐type calcium channels activates a transient large‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ current in mouse neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 23, 3639–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull A. V. and Rivier C. (1995) Regulation of the HPA axis by cytokines. Brain Behav. Immun. 9, 253–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali S., Leiss V., Karl R., Hofmann F. and Welling A. (2006) Characterization of voltage‐dependent sodium and calcium channels in Mouse pancreatic A‐ and B‐cells. J. Physiol. 572, 691–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenberg H. S., Päth G., Vögeli T. A., Scherbaum W. A. and Bornstein S. R. (2002) Role of interleukin‐6 in stress response in normal and tumorous adrenal cells and during chronic inflammation. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 966, 304–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L., McKinlay C., Gage P. and Ewart G. (2004) SARS coronavirus E protein forms cation‐selective ion channels. Virology 330, 322–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L., Gage P. and Ewart G. (2006) Hexamethylene amiloride blocks E protein ion channels and inhibits coronavirus replication. Virology 353, 294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman R. J. and Axelrod J. (1966) Control of enzymatic synthesis of adrenaline in the adrenal medulla by adrenal cortical steroids. J. Biol. Chem. 241, 2301–2305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. and Lipscombe D. (2001) Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha(1) L‐type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J. Neurosci. 21, 5944–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P. S., Alseikhan B. A., Hiel H., Grant L., Mori M. X., Yang W., Fuchs P. A. and Yue D. T. (2006) Switching of Ca2+‐dependent inactivation of Ca(v)1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 26, 10677–10689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xu Y., Song H., Rodriguez J., Tuteja D., Namkung Y., Shin H. S. and Chiamvimonvat N. (2002) Functional roles of Ca(v)1.3 (alpha(1D)) calcium channel in sinoatrial nodes: insight gained using gene‐targeted null mutant mice. Circ. Res. 90, 981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. Z. and Jones S. B. (1993) Involvement of central vs. peripheral mechanisms in mediating sympathoadrenal activation in endotoxic rats. Am. J. Physiol. 265, R683–R688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. and Misler S. (1995) Action potential‐induced quantal secretion of catecholamines from rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3498–3505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]