Abstract

Objectives

To report the overall survival (OS) outcomes of patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (nccRCC) treated at our institution with a cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) and better understand the clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients that respond best.

Material and methods

We queried our prospectively maintained database for patients who underwent CN for nccRCC between 1989–2018. Histology was reviewed by an expert genitourinary pathologist, and nccRCC tumors were subdivided into papillary (pRCC), unclassified (uRCC), chromophobe (chRCC) and other histology. Baseline clinicopathology, treatments and survival outcomes were recorded. Preoperative hematological parameters including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were analyzed. Significant univariate predictors of OS were tested in a multivariate model.

Results

There were 100 nccRCC patients treated with CN. Median age was 61 years (IQR: 48–69) and 65% were male. There were 79 patient deaths with a median OS of 13.7 months (10.8–27.2). Estimated 2- and 5-year survival was 40.1% and 12.2%, respectively. Median follow-up of survivors was 13 months (IQR: 3–30). On multivariate analysis, increasing NLR (HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.14–1.40, p<0.001) and sarcomatoid features (HR 2.18; 95% CI 1.19–3.97, p=0.014) conferred worse OS and the presence of papillary features were a favorable prognostic feature (HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.21–0.65, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Overall survival outcomes in patients with nccRCC who underwent a CN are consistently modest throughout the study period. Patients with papillary features and a lower preoperative NLR may be better candidates for a CN.

Keywords: Cytoreductive nephrectomy, kidney, renal cell carcinoma, non-clear cell histology, prognosis

Introduction

In 2019, there will be an estimated 73,820 Americans diagnosed with kidney cancer, predominantly renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and 14,770 deaths from kidney cancer [1]. RCC encompasses a collection of different morphological subtypes, with approximately 70% classified as clear cell RCC (ccRCC), and the remaining histologies often grouped into the category of non-clear cell RCC (nccRCC) [2]. Biologically, nccRCC behaves differently from ccRCC by metastasizing less frequently, but when metastases occur, nccRCC confers a worse prognosis than ccRCC [3]. Level one evidence from the United States and Europe demonstrated a significant survival advantage in ccRCC of approximately five months for cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) compared with Interferon alone [4–6]. A survival benefit was presumed in patients with nccRCC, but no level one evidence evaluating the therapeutic effect of CN in this population of kidney cancer patients exists. More recent clinical trials have questioned the benefit of CN for ccRCC compared with Sunitinib [7, 8]. While surgeons and oncologists initially applied the same approach to patients with nccRCC histology, it became evident that nccRCC is less responsive to conventional cytokine and targeted therapies used in ccRCC [9, 10]. Therefore, we sought to determine the impact of a CN on overall survival (OS) in patients with nccRCC and identify any prognostic factors that predict improved patient outcomes.

The diagnosis and management of patients with nccRCC has evolved over time. The last 15 years has seen systemic therapy options for patients with metastatic RCC expanding, with the introduction of tyrosine kinase and checkpoint blockade inhibitors. Furthermore, the classification of RCC subtypes has changed over time [11]. Few studies and case series have published the outcomes from CN in patients with nccRCC, with 2-year survival reported at 25–50% [12–16]. Most retrospective studies comparing CN with systemic therapy alone report that CN improves survival for ccRCC and nccRCC, yet these studies are limited by selection biases [17]. Due to the low volume of cytoreductive nephrectomies for nccRCC, recent studies have come from population databases, however, these studies are limited by similar selection biases as single center case series and by a lack of a centralized pathology review, likely making it difficult to draw concrete conclusions about nccRCC histologic subtypes that are challenging to classify.

Therefore, we reviewed patients undergoing a CN for nccRCC at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), using modern pathological tools to provide histological granularity and relevance to contemporary management. We aimed to report our experience with this operation, describe treatment outcomes and identify patient, pathological and hematological characteristics that are associated with prognosis after CN.

Material and methods

Following Institutional Review Board approval, we queried our prospectively collated nephrectomy database for all metastatic RCC patients treated at MSKCC from July 1989 – May 2018 (n=986). We included all patients with nccRCC histology that had metastatic disease at the time of nephrectomy (n=80) and patients diagnosed as metastatic within 90 days of nephrectomy (n=24).

All patient records were individually reviewed to ensure data accuracy. All available pathology specimens were re-reviewed by a dedicated genitourinary pathologist (YBC), blinded to patient outcomes, of which eight diagnoses were subsequently reclassified: two as ccRCC, four as a different nccRCC subtype, and two as not RCC. The remaining 100 nccRCC histological subtypes were grouped as papillary RCC (pRCC) (n=24), chromophobe RCC (chRCC) (n=15), unclassified RCC (uRCC) (n=36) and other nccRCC (n=25). Patients with uRCC and MiT family translocation RCC (tRCC) were further assessed by pathologists for the presence of papillary features, defined as a large component of multinodular and/or intracytic papillary growth [18]. Given the heterogeneous architectural patterns of uRCC and tRCC, a positive finding of papillary features was recorded when this component constituted >25% of the assessable tumor areas.

Preoperative clinicopathological factors and postoperative management were explored. Hematological parameters prior to surgery were recorded where available, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and published biomarkers predictive for patient outcomes: hemoglobin, platelet, neutrophil, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and calcium [19, 20]. All laboratory values were treated as continuous variables, described with the median and interquartile range (IQR). LDH values were measured preoperatively in 55% of patients, limiting the ability to explore the use of risk stratification tools designed for metastatic ccRCC.

The main study outcome was OS. Estimated OS was first evaluated univariately via a Cox proportional hazards model. Time from the procedure to death from kidney cancer or last follow-up was recorded. Death from kidney cancer was considered as the event, and patients were censored at the date of last follow-up. Significant univariate predictors for OS were added into a multivariate model, and stepwise regression was employed until all variables were independently significant. For each significant variable, a Kaplan-Meier curve was used to illustrate the estimated effect on OS, with survivors censored at their last follow-up date. Continuous variables were stratified by their median value, and the log-rank test was used to compare the estimated survival. All statistical analyses were two sided and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.1 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Among 100 nccRCC patients, 65% of the cohort were male and the median age was 61 years (IQR: 48–69). Patients predominantly had a good performance status, with 90% having a Karnofsky Performance Status ≥80. Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathological characteristics of the study cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline cohort characteristics

| Variable | n = 100 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 35 (35%) |

| Male | 65 (65%) |

| Age | 61 (48, 69) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 5 (5.0%) |

| Black | 12 (12%) |

| White | 75 (75%) |

| Unknown | 8 (8.0%) |

| BMI | 27.4 (22.9, 30.3) |

| Unknown | 1 |

| KPS | |

| <80 | 9 (10%) |

| ≥80 | 81 (90%) |

| Unknown | 10 |

| Smoking history | |

| Current | 3 (3.0%) |

| Former | 42 (42%) |

| Never | 54 (55%) |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes | 11 (11%) |

| No | 85 (89%) |

| Unknown | 4 |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 41 (43%) |

| No | 55 (57%) |

| Unknown | 4 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |

| Yes | 19 (20%) |

| No | 77 (80%) |

| Unknown | 4 |

| Prior cancer | |

| Yes | 13 (13%) |

| No | 86 (87%) |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Family history of cancer | |

| Yes | 66 (67%) |

| No | 33 (33%) |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Therapeutic era | |

| Post-2005 | 77 (77%) |

| Pre-2005 | 23 (23%) |

| Tumor side | |

| Left | 60 (60%) |

| Right | 40 (40%) |

| Tumor size | 8.4 (6.0, 13.2) |

| Pathological tumor stage | |

| ≤T2 | 26 (26%) |

| ≥T3 | 74 (74%) |

| Nodal stage | |

| N0/NX | 40 (40%) |

| N+ | 60 (60%) |

| Histology | |

| Chromophobe (chRCC) | 15 (15%) |

| Other RCC | 25 (25%) |

| Papillary (pRCC) | 24 (24%) |

| Unclassified (uRCC) | 36 (36%) |

| Papillary features | |

| Present | 39 (39%) |

| Absent | 61 (61%) |

| Sarcomatoid dedifferentiation | |

| Present | 25 (26%) |

| Absent | 72 (74%) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Necrosis | |

| Present | 30 (31%) |

| Absent | 67 (69%) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Neutrophil | 5.65 (4.20, 7.12) |

| Unknown | 20 |

| Lymphocyte | 1.40 (1.05, 1.80) |

| Unknown | 21 |

| Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio | 4.00 (2.80, 5.66) |

| Unknown | 21 |

| Hemoglobin | 12.20 (10.80, 13.70) |

| Unknown | 11 |

| Platelets | 303 (226, 384) |

| Unknown | 11 |

| Calcium | 9.30 (8.90, 9.60) |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 191 (160, 264) |

| Unknown | 45 |

Note: Hemoglobin has been gender adjusted by adding 0.5 to all females

Of the four histological groups, 15 patients had chRCC, 24 patients had pRCC, 36 patients had uRCC and 25 patients were classified as other nccRCC. Other nccRCC included collecting duct (n=6), renal medullary carcinoma (n=4) and tRCC (n=2). Pathologists identified papillary features in 39 tumors: pRCC (n=24), uRCC (n=13) and tRCC (n=2). The chRCC tumors were larger (p=0.023) and had a higher proportion that exhibited sarcomatoid features (p=0.020). Other nccRCC tumors occurred in younger patients (p<0.001). (Supplementary Table 1)

Median follow-up of survivors was 13.3 months (3–30.4). Preoperatively, seven patients received systemic therapy. Two patients had a significant therapeutic response, four experienced mixed responses with toxicity (hematuria (n=3), gastrointestinal (n=1)), and one did not respond and had a nephrectomy performed between systemic treatments. Postoperatively, 64 patients received systemic therapy, 34 patients did not and two were unknown. Most cytoreductive nephrectomies were performed after the introduction of targeted therapies (2006 – 2018) and the majority of patients received targeted therapy as their first-line treatment (Table 1). Ultimately, all patients’ deaths were cancer-related, with 79 patients dying and a median OS of 13.7 months (10.8 – 27.2). Estimated 2- and 5-year OS were 40.1% and 12.2%, respectively.

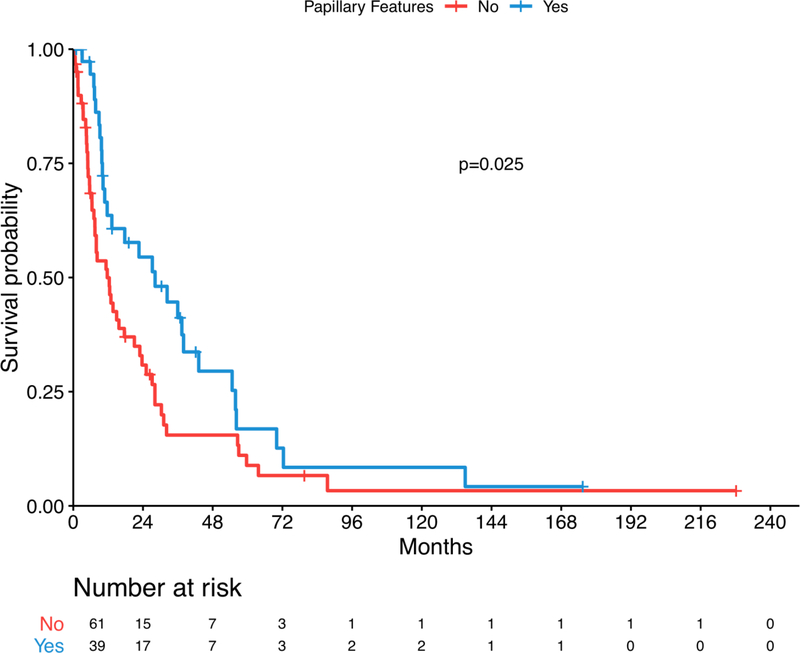

On univariate analysis, pathological tumor stage ≥T3, node positive disease, presence of sarcomatoid features, increasing neutrophil count, decreasing lymphocyte count, increasing NLR, increasing hemoglobin and increasing platelets were associated with poor survival outcomes. (Table 2) Survival did not vary significantly between four histological subtypes. However, the presence of papillary features among pRCC, uRCC and tRCC tumors, was associated with a survival benefit on univariate and multivariate analysis (HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.21 – 0.65, p<0.001). (Figure 1) The presence of sarcomatoid features in the primary tumor specimen was a predictor of worse OS on univariate and multivariate analysis (HR 2.18; 95% CI 1.19 – 3.97, p=0.014). (Figure 2) (Table 3)

Table 2.

Overall survival: univariate analysis

| Variable | Number | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 100 | 0.5 | ||

| Female | Ref. | |||

| Male | 1.16 | 0.73 – 1.85 | ||

| Age | 100 | 0.99 | 0.97 – 1.00 | 0.10 |

| Race | 100 | 0.8 | ||

| Asian | Ref. | |||

| Black | 1.31 | 0.35 – 4.89 | ||

| White | 1.55 | 0.43 – 7.52 | ||

| Unknown | 1.79 | 0.48 – 4.96 | ||

| BMI | 99 | 1.00 | 0.97 – 1.04 | 0.8 |

| KPS | 90 | 0.2 | ||

| <80 | Ref. | |||

| ≥80 | 0.57 | 0.28 – 1.17 | ||

| Smoking history | 99 | 0.7 | ||

| Current | Ref. | |||

| Former | 1.58 | 0.48 – 5.20 | ||

| Never | 1.38 | 0.42 – 4.49 | ||

| Diabetes | 96 | 0.13 | ||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.70 | 0.89 – 3.23 | ||

| Hypertension | 96 | 0.5 | ||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.54 – 1.36 | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 96 | >0.9 | ||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.58 – 1.73 | ||

| Prior cancer | 99 | 0.7 | ||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.57 – 2.20 | ||

| Family history of cancer | 99 | 0.7 | ||

| No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.67 – 1.76 | ||

| Therapeutic era | 100 | 0.5 | ||

| Cytokine Era | Ref. | |||

| Targeted Era | 1.21 | 0.72 – 2.03 | ||

| Tumor side | 100 | 0.6 | ||

| Left | Ref. | |||

| Right | 1.12 | 0.71 – 1.78 | ||

| Tumor size | 99 | 1.02 | 0.97 – 1.06 | 0.5 |

| Pathological tumor stage | 100 | 0.009 | ||

| ≤T2 | Ref. | |||

| ≥T3 | 1.97 | 1.15 – 3.35 | ||

| Nodal stage | 100 | 0.005 | ||

| N0/NX | Ref. | |||

| N+ | 1.94 | 1.21 – 3.12 | ||

| Histology | 100 | 0.2 | ||

| Chromophobe (chRCC) | Ref. | |||

| Other RCC | 1.61 | 0.78 – 3.30 | ||

| Papillary (pRCC) | 0.79 | 0.40 – 1.56 | ||

| Unclassified (uRCC) | 1.08 | 0.56 – 2.09 | ||

| Sarcomatoid dedifferentiation | 97 | 0.002 | ||

| Absent | Ref. | |||

| Present | 2.27 | 1.38 – 3.73 | ||

| Necrosis | 97 | 0.4 | ||

| Absent | Ref. | |||

| Present | 1.22 | 0.75 – 1.97 | ||

| Papillary features | 100 | 0.025 | ||

| Absent | Ref. | |||

| Present | 0.60 | 0.38 – 0.95 | ||

| Neutrophil | 80 | 1.34 | 1.17 – 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte | 79 | 0.54 | 0.29 – 1.02 | 0.025 |

| Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio | 79 | 1.27 | 1.16 – 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 89 | 0.84 | 0.75 – 0.94 | 0.004 |

| Platelets | 89 | 1.00 | 1.00 – 1.01 | <0.001 |

| Calcium | 84 | 0.99 | 0.58 – 1.68 | >0.9 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 55 | 1.00 | 1.00 – 1.00 | 0.2 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival estimate stratified by papillary features

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival estimate stratified by sarcomatoid features

Table 3.

Overall survival: multivariate analysis

| N=79 | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological tumor stage | 0.052 | ||

| ≤T2 | Ref. | ||

| ≥T3 | 1.91 | 0.97 – 3.74 | |

| Sarcomatoid differentiation | 0.014 | ||

| Absent | Ref. | ||

| Present | 2.18 | 1.19 – 3.97 | |

| Papillary Features | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | Ref. | ||

| Present | 0.37 | 0.21 – 0.65 | |

| NLR | 1.27 | 1.14 – 1.40 | <0.001 |

There were 79 patients with NLR data available. Median preoperative NLR value was 4.00 (IQR: 2.80 – 5.66). No significant difference was found in the NLR scores between the histological subtypes (p=0.8). When NLR was dichotomized by the median value, patients with a low NLR had better overall survival (p=0.004) (Figure 3). On multivariate Cox-regression analysis, an increasing preoperative NLR was a significant independent predictor of all-cause mortality (HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.14 – 1.40, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival estimate stratified by NLR

Discussion

Non-clear cell variants of metastatic RCC are aggressive, difficult to treat and less studied to date. This study sought to characterize patient outcomes following CN for nccRCC. The review, spanning 29 years, represents the largest reported cohort of nccRCC CN from a single institution, and included a centralized histology review using current diagnostic criteria and ancillary tools. Patients had a 2- and 5-year OS of 40.1% and 12.2%, respectively. Increased NLR and sarcomatoid features conferred worse OS and the presence of papillary features were associated with improved survival.

CN for nccRCC is uncommon, therefore most studies to date have relied on pooled-institutional and population databases. A meta-analysis of patients with either ccRCC or nccRCC demonstrated an improved survival for patients treated with a CN compared with systemic therapy only, although the outcomes are modest [17]. Heng et al reported the results of CN for nccRCC across 30 different institutions, showing a median survival of 15.3 months [13]. Additionally, in two separate SEER-based studies, Airzer et al between 2004–2009 and Marchioni et al between 2010–2014 reported a 2-year cancer-specific mortality rate of 59.2% and 52.6% after CN for patients with nccRCC, respectively [12, 15]. These outcomes are similar to our experience, highlighting the shorter survival after CN for nccRCC compared with ccRCC [21]. However, multi-institutional and population based studies are limited by no centralized pathological review and often have restrictions on reportable outcomes.

Few single center series have evaluated the role of CN in patients with nccRCC [14, 16]. In the largest previously published single institution analysis investigating CN between 1991–2006, Kassouf et al. reported 92 nccRCC cytoreductive cases with a 2-year overall survival of 24%. Moreover, they described an increased proportion of patients with nodal disease, however, surprisingly, this was reported to be a favorable feature in their cohort [14]. Carrasco et al reviewed the Mayo Clinic’s experience of 505 cytoreductive nephrectomies between 1970–2008, including 40 with nccRCC [16]. This cohort consisted of 57.5% of patients with papillary RCC, reporting 3-year cancer-specific survival of 22% for nccRCC patients, similar to the 25.7% (17.7% – 37.1%) 3-year survival in our cohort.

The role and timing of CN as part of the multimodal management of ccRCC is evolving, especially with new effective systemic therapies being introduced. The rationale for cytoreduction in ccRCC and nccRCC is to debulk a potentially immunosuppressive disease, avoid the seeding of new metastases and to manage local symptoms and systemic paraneoplastic symptoms. The CARMENA trial evaluated the effect of CN in ccRCC on OS [7], however, given that treatment outcomes in nccRCC are different, it is important to test the impact of CN over time in this population. Therefore, we evaluated the outcomes of patients treated across the cytokine and targeted therapy eras, to explore the impact of newer treatments. In our cohort, we did not find a significant difference in OS across these eras and, given that baseline patient characteristics did not differ significantly over time, this highlights the inefficacy of newer therapies in this population. This is further supported by the comparable survival outcomes that were described in earlier single center studies and more recent population studies. The seven patients that received systemic therapy prior to a delayed nephrectomy did not have improved OS. Finally, a third of the cohort did not receive systemic therapy after cytoreductive nephrectomy; they included patients with stable metastases observed and untreated to last follow-up, and patients with rapidly progressive metastases unfit for systemic therapy. However, with the advent of newer immunotherapy, renewed investigation will be required to reevaluate the role of CN in this therapeutic era [14].

With diagnoses covering multiple decades, it was important to undertake in-house specimen review to ensure that the diagnoses were consistent with contemporary RCC classification. The uRCC tumors contributed the largest proportion of the cytoreductive cases. These tumors could be subdivided into those with and without papillary features. All four groups of nccRCC were aggressive, despite the relatively indolent courses that may be ascribed in localized presentations.

On multivariate analysis, we found that sarcomatoid features, increased NLR and papillary features were predictive for patient outcomes. Sarcomatoid differentiation was present in 26% of the cohort, with previous studies also finding the presence of sarcomatoid features to be associated with a poor prognosis following CN in both ccRCC and nccRCC [22, 23]. While not statistically significant on multivariate analysis (p=0.052), pathological tumor stage ≥T3 had an increased hazard (1.91) for OS following cytoreduction, consistent with other studies of CN in ccRCC [24].

Papillary features among patients with nccRCC is an interesting favorable pathological feature. We have previously reported this finding in a clinical trial of advanced nccRCC treated with Everolimus plus Bevacizumab [18]. The heterogeneous nature of our cohort suggests that papillary features may confer a more indolent disease course in the metastatic setting in general. As this cohort was diagnosed from the primary tumor specimen, future research efforts may help determine whether this is a finding that can be reliably detected through a preoperative biopsy to assist in patient selection for CN.

While hemoglobin, platelets, lymphocyte and neutrophil values were all predictive of OS on univariate analysis, the NLR was the only hematological parameter that was significant on multivariate regression analysis. Interestingly, this parameter is not present in established ccRCC risk scores. Although the preoperative NLR is a non-specific snapshot, which may vary with non-oncological events including stress, trauma and infections, it has previously been demonstrated to predict poor oncological outcomes for genitourinary cancers [25, 26]. Furthermore, an elevated NLR has also been associated with reduced survival following CN in patients with ccRCC, where tumors have a well described immune system interaction [27–30]. However, the impact of changes in the NLR has not been studied in CN for patients with nccRCC. Further research into the associations between the NLR and events within the tumor microenvironment may help to better characterize the role of this prognostic marker.

Limitations to this study exist in the cohort design and its retrospective nature, thereby allowing intrinsic biases that may affect the results. Patients with nccRCC are a heterogeneous group, from which we have a relatively small sample size and a diverse range of histologies. Conversely, the strength of limiting the analysis to this institution was that we were able to undertake a pathological re-review utilizing our centralized tumor repository. Our findings, particularly those relying on pathological inferences, will require external validation. Additionally, although prognostic stratification has been designed for patients with metastatic ccRCC initiating systemic therapy [19, 20], these prognostic models have not been used for survival following CN in patients with nccRCC, so it is unclear whether they would have utility for this population. Finally, this study does not account for the volume and location of metastatic disease. While difficult to quantify uniformly retrospectively, this could represent an avenue for future research into the management of metastatic nccRCC.

Conclusion

Our study has identified predictors of OS outcomes following CN for nccRCC. Sarcomatoid differentiation and an increased preoperative NLR were associated with adverse OS, while tumors exhibiting papillary features had a more indolent OS. These variables identified may help in selecting suitable candidates for CN in metastatic nccRCC. Future studies using a preoperative biopsy to identify papillary and sarcomatoid features are needed to validate this information.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Median survival of 13.7 months for cytoreductive nephrectomy in non-clear cell RCC

Sarcomatoid differentiation has poorer overall survival

Papillary features are favorable for improved overall survival

Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is a significant predictor of survival

Despite expanding options for systemic therapy, outcomes haven’t improved over time

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Disclosures: The authors have no relevant disclosures pertaining to this review

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. European Urology. 2016;70:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Mariani T, Russo P, Mazumdar M, Reuter V. Treatment outcome and survival associated with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of non-clear-cell histology. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, Bearman SI, Roy V, McGrath PC, et al. Nephrectomy Followed by Interferon Alfa-2b Compared with Interferon Alfa-2b Alone for Metastatic Renal-Cell Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1655–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mickisch GHJ, Garin A, van Poppel H, de Prijck L, Sylvester R. Radical nephrectomy plus interferonalfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2001;358:966–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, Tangen C, Van Poppel H, Crawford ED. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol. 2004;171:1071–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mejean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Colas S, Beauval JB, Bensalah K, et al. Sunitinib Alone or after Nephrectomy in Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bex A, Mulders P, Jewett M, Wagstaff J, van Thienen JV, Blank CU, et al. Comparison of Immediate vs Deferred Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients with Synchronous Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Sunitinib: The SURTIME Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Voss MH, Bastos DA, Karlo CA, Ajeti A, Hakimi AA, Feldman DR, et al. Treatment outcome with mTOR inhibitors for metastatic renal cell carcinoma with nonclear and sarcomatoid histologies. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:663–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bellmunt J, Dutcher J. Targeted therapies and the treatment of non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24:1730–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aizer AA, Urun Y, McKay RR, Kibel AS, Nguyen PL, Choueiri TK. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic non-clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). BJU Int. 2014;113:E67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Heng DYC, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B, Lee J-L, Knox JJ, et al. Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients with Synchronous Metastases from Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. European Urology. 2014;66:704–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kassouf W, Sanchez-Ortiz R, Tamboli P, Tannir N, Jonasch E, Merchant MM, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma with nonclear cell histology. J Urol. 2007;178:1896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marchioni M, Bandini M, Preisser F, Tian Z, Kapoor A, Cindolo L, et al. Survival after Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Metastatic Non-clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients: A Population-based Study. Eur Urol Focus. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Carrasco A, Thompson RH, Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, Boorjian SA. The impact of histology on survival for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy. Indian journal of urology : IJU : journal of the Urological Society of India. 2014;30:38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bhindi B, Abel EJ, Albiges L, Bensalah K, Boorjian SA, Daneshmand S, et al. Systematic Review of the Role of Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in the Targeted Therapy Era and Beyond: An Individualized Approach to Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. European Urology. 2019;75:111–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Voss MH, Molina AM, Chen YB, Woo KM, Chaim JL, Coskey DT, et al. Phase II Trial and Correlative Genomic Analysis of Everolimus Plus Bevacizumab in Advanced Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3846–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bex A, Albiges L, Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Dabestani S, Giles RH, et al. Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines for Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Patients with Synchronous Metastatic Clear-cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. European Urology. 2018;74:805–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Culp SH, Tannir NM, Abel EJ, Margulis V, Tamboli P, Matin SF, et al. Can we better select patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma for cytoreductive nephrectomy? Cancer. 2010;116:3378–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shuch B, Said J, La Rochelle JC, Zhou Y, Li G, Klatte T, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy for kidney cancer with sarcomatoid histology--is up-front resection indicated and, if not, is it avoidable? J Urol. 2009;182:2164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Culp SH, Karam JA, Wood CG. Population-based analysis of factors associated with survival in patients undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy in the targeted therapy era. Urologic oncology. 2014;32:561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mano R, Baniel J, Shoshany O, Margel D, Bar-On T, Nativ O, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts progression and recurrence of non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2015;33:67.e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lorente D, Mateo J, Templeton AJ, Zafeiriou Z, Bianchini D, Ferraldeschi R, et al. Baseline neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second-line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26:750–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Peyton CC, Abel EJ, Chipollini J, Boulware DC, Azizi M, Karam JA, et al. The Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients Undergoing Cytoreductive Nephrectomy with Thrombectomy. European Urology Focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fukuda H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Shimizu S, Tanabe K. Predictive value of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with cytoreductive nephrectomy. Oncotarget. 2018;9:14296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Baum YS, Patil D, Huang JH, Spetka S, Torlak M, Nieh PT, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be associated with decreased overall survival in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy. Asian journal of urology. 2016;3:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ohno Y, Nakashima J, Ohori M, Tanaka A, Hashimoto T, Gondo T, et al. Clinical variables for predicting metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients who might not benefit from cytoreductive nephrectomy: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and performance status. International journal of clinical oncology. 2014;19:139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.