Abstract

Background

Buerger's disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) is a non‐atherosclerotic, segmental inflammatory pathology that most commonly affects the small and medium sized arteries, veins, and nerves in the upper and lower extremities. The aetiology is unknown, but involves hereditary susceptibility, tobacco exposure, immune and coagulation responses. In many cases, there is no possibility of revascularisation to improve the condition. Pharmacological treatment is an option for patients with severe complications, such as ischaemic ulcers or rest pain.This is an update of the review first published in 2016.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of any pharmacological agent (intravenous or oral) compared with placebo or any other pharmacological agent in patients with Buerger's disease.

Search methods

The Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AMED, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov trials register to 15 October 2019. The review authors searched LILACS, ISRCTN, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, EU Clinical Trials Register, clincialtrials.gov and the OpenGrey Database to 5 January 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving pharmacological agents used in the treatment of Buerger's disease.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors, independently assessed the studies, extracted data and performed data analysis.

Main results

No new studies were identified for this update. Five randomised controlled trials (total 602 participants) compared prostacyclin analogue with placebo, aspirin, or a prostaglandin analogue, and folic acid with placebo. No studies assessed other pharmacological agents such as cilostazol, clopidogrel and pentoxifylline or compared oral versus intravenous prostanoid.

Compared with aspirin, intravenous prostacyclin analogue iloprost improved ulcer healing (risk ratio (RR) 2.65; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 6.11; 98 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence), and helped to eradicate rest pain after 28 days (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.48 to 3.52; 133 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence), although amputation rates were similar six months after treatment (RR 0.32; 95% CI 0.09 to 1.15; 95 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence).

When comparing prostacyclin (iloprost and clinprost) with prostaglandin (alprostadil) analogues, ulcer healing was similar (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.69; 89 participants; 2 studies; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence), as was the eradication of rest pain after 28 days (RR 1.57; 95% CI 0.72 to 3.44; 38 participants; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence), while amputation rates were not measured.

Compared with placebo, the effects of oral prostacyclin analogue iloprost were similar for: healing ischaemic ulcers (iloprost 200 mcg: RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.54 to 2.29; 133 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence, and iloprost 400 mcg: RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.93; 135 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence), eradication of rest pain after eight weeks (iloprost 200 mcg: RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.63; 207 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence, and iloprost 400 mcg: RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.59; 201 participants; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence), and amputation rates after six months (iloprost 200 mcg: RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.19 to 1.56; 209 participants; 1 study, and iloprost 400 mcg: RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.31; 213 participants; 1 study).

When comparing folic acid with placebo in patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia, pain scores were similar, there were no new cases of amputation in either group, and ulcer healing was not assessed (very low‐certainty evidence).

Treatment side effects such as headaches, flushing or nausea were not associated with treatment interruptions or more serious consequences. Outcomes such as amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking distance, and ankle brachial index were not assessed by any study.

Overall, the certainty of the evidence was very low to moderate, with few studies, small numbers of participants, variation in severity of disease of participants between studies and missing information (for example regarding baseline tobacco exposure).

Authors' conclusions

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that intravenous iloprost (prostacyclin analogue) is more effective than aspirin for eradicating rest pain and healing ischaemic ulcers in Buerger’s disease, but oral iloprost is not more effective than placebo. Very low and low‐certainty evidence suggests there is no clear difference between prostacyclin (iloprost and clinprost) and the prostaglandin analogue alprostadil for healing ulcers and relieving pain respectively in severe Buerger’s disease. Very low‐certainty evidence suggests there is no clear difference in pain scores and amputation rates between folic acid and placebo, in people with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia. Further well designed RCTs assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological agents (intravenous or oral) in people with Buerger's disease are needed.

Plain language summary

Pharmacological treatment (drugs) for Buerger's disease

Background

Buerger's disease is characterised by recurring progressive inflammation and clotting in small and medium arteries and veins of the hands and feet. Its cause is unknown, but it is most common in men with a history of tobacco use. It is responsible for ulcers and extreme pain in the limbs of young smokers. In many cases, mainly in patients with the most severe form, there is no possibility of improving the condition with surgery, and therefore, drugs (pharmacological agents) are used. These can be pharmacological agents, such as cilostazol, clopidogrel, and pentoxifylline, or medicine derivatives of prostacyclin and prostaglandin, which redirect blood flow and improve the circulation in affected areas, and might help to heal ulcers and relieve rest pain. This review assessed the effectiveness of pharmacological agents in the treatment of patients with Buerger's disease.

Key results

Our search identified five randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with a total of 602 participants and a treatment period of around four weeks (evidence current until 15 October 2019). The comparisons included prostacyclin analogue versus placebo, aspirin, and a prostaglandin analogue, and folic acid versus placebo. We did not identify studies that assessed pharmacological agents such as cilostazol, clopidogrel and pentoxifylline, or studies that compared oral prostanoid versus prostanoid given intravenously (administered into the vein by injection or infusion). The included studies assessed derivatives of prostacyclin and prostaglandin, which have the ability to redirect blood flow and improve the circulation in affected areas.

Moderate‐certainty evidence from one study suggested that intravenous iloprost was effective in healing ulcers and relieving rest pain after 28 days of treatment when compared with oral aspirin, but no clear differences were found in the rates of amputation. Evidence from two studies suggested that prostacyclin was as effective as prostaglandin analogues in healing ulcers (very low‐certainty evidence) and eradicating pain at rest (low‐certainty evidence), but rates of amputation were not assessed. Moderate‐certainty evidence from one study suggested that there was no clear difference between placebo and the oral prostacyclin analogue iloprost (200 mcg and 400 mcg) in healing ischaemic ulcers or eradicating pain at rest after eight weeks and six months, and rates of amputation after six months. Very low‐certainty evidence from one study showed no clear difference between placebo and folic acid, in patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia (a medical condition characterised by abnormally high level of homocysteine in the blood), in rates of amputation and pain scores. Ulcer healing was not measured. Treatment side effects, such as headaches or nausea, did not result in treatment interruptions or more serious consequences. Outcomes such as amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking distance, and ankle brachial index were not assessed by any study.

Certainty of the evidence

Overall, the certainty of the evidence was very low to moderate. we downgraded the certainty of the evidence because of the small numbers of studies, small numbers of participants, variation in severity of disease of participants between studies, and missing information (for example baseline tobacco exposure information). Further well designed RCTs assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological agents (intravenous or oral) in people with Buerger's disease are needed.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Buerger's disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) is a non‐atherosclerotic, segmental inflammatory pathology that most commonly affects the small and medium sized arteries, veins and nerves in the upper and lower extremities (Olin 2000). Von Winiwarter first described a patient with the disease in 1879 (von Winiwarter 1879), but it was Leo Buerger, in 1908, who published a detailed description of the pathological findings on amputated limbs and named the disease (Buerger 1908).

The prevalence of the disease among all patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) varies from as low as 0.5% to 5.6% in Western Europe to as high as 45% to 63% in India, and 16% to 66% in Korea and Japan (Cachovan 1988; Malecki 2009; Olin 2000).

The etiology is unknown, but involves hereditary susceptibility, tobacco exposure, immune and coagulation responses (Malecki 2009). Currently, a possible infectious etiology is gaining interest, especially after the findings of micro‐organisms of the oral flora in occlusive thrombi in patients with Buerger's disease and moderate to severe periodontitis (Iwai 2005; Li 2008). Another hypothesis is the possible pathogenic role of rickettsial infection in Buerger's disease (Bartolo 1987; Fazeli 2013). Features distinguishing Buerger's disease from atherosclerosis include the pathology distribution (with involvement of both the upper and lower extremities), associated superficial venous thrombosis, a paucity of atherosclerotic risk factors and normal proximal large arteries (Weinberg 2012).

Diagnosis and complications

The typical patient with Buerger's disease is a young man (younger than 40 or 45 years) with a history of tobacco use, who presents with progressive claudication, ischaemic ulcers, or pain at rest (Olin 2000); approximately 76% of patients have ischaemic ulcerations at the time of presentation (Olin 2006). To date, there are no unanimous diagnostic criteria for Buerger's disease. The most commonly used are Shionoya's criteria, which comprise: (1) smoking history; (2) onset of symptoms before the age of 50 years; (3) infrapopliteal arterial occlusions; (4) either arm involvement or phlebitis migrans; and (5) absence of atherosclerotic risk factors other than smoking (Shionoya 1983). All criteria should be present. The disease is usually confined to the distal circulation and is almost always infrapopliteal in the legs and distal to the brachial artery in the arms (Olin 2000). In fact, the distal and diffuse nature of the disease culminates in critical limb ischaemia (CLI) in approximately 76% to 81% of patients, with poor chances of revascularisation (Olin 2006). In patients diagnosed with limb ischaemia, as in Buerger's disease, the clinical evaluation is done according to the Rutherford classification and the Fontaine stages. The Rutherford classification for PAD has seven categories. These are: (0) asymptomatic; (1) mild claudication; (2) moderate claudication; (3) severe claudication; (4) rest pain; (5) minor tissue loss, non‐healing ulcer or focal gangrene with diffuse pedal ischaemia; (6) major tissue loss extending above the transmetatarsal level; and (7) a functional foot that is no longer salvageable (Rutherford 2005). The Fontaine classification has four stages: (I) asymptomatic; (II) intermittent claudication (IC); (III) rest pain; (IV) ulceration or gangrene, or both (Fontaine 1954). Novo 2004 described a modified Fontaine classification, the Leriche‐Fontaine classification: (I) asymptomatic or effort pain; (IIA) effort pain or pain‐free walking distance further than 200 metres; (IIB) pain‐free walking distance less than 200 metres; (IIIA) rest pain, ankle arterial pressure higher than 50 mm Hg; (IIIB) rest pain, ankle arterial pressure lower than 50 mm Hg; (IV) trophic lesions, necrosis or gangrene (Novo 2004). According to Cooper 2004, the risk of any extremity amputation during 15.6 years of follow‐up in patients with Buerger's disease is 25% at five years, 38% at 10 years and 46% at 20 years.

Description of the intervention

In patients with CLI and poor chances of revascularisation, as seen in many patients diagnosed with Buerger's disease, pharmacological treatment is given to improve the blood flow (perfusion) in the affected extremity. The most commonly used pharmacological agents are aspirin, cilostazol (Bedenis 2014; Ruffolo 2010), prostanoids (Malecki 2009), and bosentan (De Haro 2009).

Aspirin is a drug that inhibits cyclo‐oxygenase, which is responsible for the synthesis of thromboxane and prostaglandins. It is important in cardiac and cerebrovascular atherosclerotic diseases, as it inhibits platelet aggregation. The most important contraindications are hypersensitivity to salicylates, active gastrointestinal ulcers, patients with hemorrhagic disorders, renal and hepatic failure, pregnancy and use in children. Aspirin is administered orally with a recommended dosage of 75 to 325 mg (Brunton 2011).

Cilostazol is a quinolinone derivative drug that inhibits cellular phosphodiesterase (more specific for phosphodiesterase III), affecting both vascular beds and cardiovascular function. It causes a non‐homogeneous dilation of vascular beds, with greater dilation in the femoral beds than in vertebral, carotid or superior mesenteric arteries. In other words, cilostazol 'steals' a small part of the blood from other territories (gastrointestinal and cerebral) to improve perfusion in ischaemic limbs. A further action of cilostazol is the reversible inhibition of platelet aggregation. Cilostazol is contraindicated in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) of any severity, haemostatic disorders or active pathologic bleeding, such as bleeding peptic ulcer and intracranial bleeding, and in patients with known or suspected hypersensitivity to cilostazol. The more common side effects of cilostazol use include headaches, diarrhoea, abnormal stools and palpitations (Chapman 2003). Cilostazol is administered orally and is available in 50 mg or 100 mg tablets. Cilostazol was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999 for the reduction of symptoms of intermittent claudication as a result of atherosclerosis (Dindyal 2009; FDA 1999).

Prostanoids (prostaglandin and prostacyclin analogues) are eicosanoid derivatives, commonly used for many conditions including pulmonary hypertension, sexual impotence, and glaucoma. Because of their short half‐life, around two to three minutes, these synthetic drugs must be administrated by continuous intravenous infusion (Safdar 2011). The development of stable prostacyclin analogues (such as iloprost) with a longer half‐life has allowed the oral use of these drugs. The most important contraindications are heart failure (caused by arrhythmias, myocardiopathy, valvulopathy, or coronary insufficiency), intracranial haemorrhage, gastrointestinal ulcers, and trauma. Side effects include headache, flushing, malaise, gastrointestinal distress and, with higher doses, hypotension. The maximum iloprost dose that is administered is around 2 ng/kg/min by continuous infusion (Grant 1992).

Bosentan is a potent and mixed endothelin‐A and endothelin‐B receptor antagonist, causing selective vasodilatory effects (Weber 1996). Some important reported side effects are hepatotoxicity and fluid retention. Bosentan is administered orally, mainly in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension, with a recommended dosage of 62.5 mg (twice daily) to 125 mg (twice daily).

How the intervention might work

Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), a thromboxane production inhibitor, is well‐known as an antiplatelet drug, and is used in heart attack and stroke prevention (Brunton 2011).

Cilostazol, a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase III, is used mainly in patients with IC, and acts as a direct arterial vasodilatator and inhibits platelet aggregation (Rutherford 2005).

Prostanoids act by binding to specific receptors in the endothelium (causing vasodilatation) and platelets (inhibiting platelet aggregation), which causes a transitory increase in arterial peripheral perfusion (Brunton 2011). Arterial vasodilatation in ischaemic areas increases blood perfusion and, consequently, increases the chances of ulcer healing and improving rest pain. Inhibiting platelet aggregation prevents the occlusion of small arteries and, therefore, stabilizes the disease.

Bosentan, a potent and mixed endothelin‐A and endothelin‐B receptor antagonist, causes selective vasodilatory effects (Weber 1996). Bosentan has been used with success in patients with digital ulcers and systemic sclerosis (Launay 2006; Matucci‐Cerinic 2011), opening the perspective for use in other conditions such as Buerger's disease (De Haro 2009).

Therefore, these pharmacological agents are used to improve perfusion in ischaemic limbs due to their vasodilatatory and antiplatelet effects. The effects may vary from agent to agent.

Why it is important to do this review

Buerger's disease is a debilitating condition which can affect active, young people. In many cases, there is possibility of revascularisation to improve the condition. Different combinations of drugs, doses and administration pathways (oral and intravenously) have been approved for use. However, to date there is no consensus about the best pharmacological treatment for patients with Buerger's disease. A systematic review is opportune and extremely relevant.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of any pharmacological agent (intravenous or oral) compared with placebo or any other pharmacological agent in patients with Buerger's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving pharmacological agents used in the treatment of Buerger's disease.

Types of participants

We included patients clinically diagnosed with Buerger's disease.

Types of interventions

We assessed any pharmacological agents used in treating patients with Buerger's disease, including drugs utilized for atherosclerotic diseases, such as aspirin or cilostazol, resulting in the possible comparisons listed below:

(Oral or intravenous) prostanoid (e.g. iloprost) versus placebo

Oral prostanoid versus intravenous prostanoid

(Oral or intravenous) prostanoid (e.g. iloprost) versus aspirin

(Oral or intravenous) prostanoid (e.g. iloprost) versus cilostazol

Aspirin versus placebo

Cilostazol versus placebo

Aspirin versus cilostazol

Any pharmacological agent versus placebo or any other pharmacological agent

Prostanoids could be either prostaglandin or prostacyclin analogues. We excluded studies that did not assess pharmacological agents in the treatment of Buerger's disease.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Ulcer healing

Pain: assessed using a validated pain score or scale, or quality of life (QoL) questionnaire

Rate of amputation: major amputation (defined as amputation of the lower or upper limb above the ankle or the wrist, respectively); and minor amputation (defined as amputation of a hand or foot or any part of)

Secondary outcomes

Amputation‐free survival

Side effects of pharmacological agents, including bleeding, headache, flushing, or nausea

Walking distance or pain‐free walking

Ankle brachial index

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist conducted systematic searches of the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web searched on 15 October 2019);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO 2019, Issue 10);

MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE® Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE® Daily and Ovid MEDLINE®) (searched from 1 January 2015 to 15 October 2019);

Embase Ovid (searched from 1 January 2015 to 15 October 2019);

CINAHL Ebsco (searched from 1 January 2015 to 15 October 2019);

AMED Ovid (searched from 1 January 2015 to 15 October 2019).

The Information Specialist modelled search strategies for other databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, they were combined with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by the Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6, Lefebvre 2011). Search strategies for major databases are provided in Appendix 1.

The Information Specialist searched the following trials registries on 15 October 2019:

the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (who.int/trialsearch);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

We, the review authors, also searched the following trial registers and databases (searched from 10 May 2015 to 5 January 2020). Search strategies used are provided in Appendix 2.

ISRCTN register (isrctn.com);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov);

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (anzctr.org.au);

The EU Clinical Trials Register (clinicaltrialsregister.eu);

LILACS, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (lilacs.bvsalud.org/).

Searching other resources

We also searched the grey literature produced in Europe by consulting the OpenGrey Database (opengrey.eu). We used the terms 'Buerger's disease'; 'thromboangiitis obliterans'; 'von Winiwarter disease'; and word variations to perform the search (searched on 5 January 2020).

We searched the reference lists of relevant articles retrieved by the electronic searches for additional citations.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two of three review authors (DGC, FCN and JCCBS) independently assessed all studies that were identified by the search strategy for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by a third author (CM).

Data extraction and management

For all eligible studies, two of three review authors (DGC, FCN and JCCBS) extracted data using the Cochrane Vascular's data extraction table. Where there were discrepancies, a third author (CM) solved disagreement. We entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (DGC and JCCBS) independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The information about the risk of bias of the included studies was presented in the form of a table and a graph.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous (categorical) data

Results were presented as summary risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

We had planned to use the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI where there was consistency in the outcome measure, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods.

Time‐to‐event data

We had planned to use hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CIs to measure the treatment effect for any time‐to‐event outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

We considered the individual participant as the unit of randomisation for a single intervention.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the contact authors of included studies with any methodological queries, but we did not receive any response. Where possible, we had planned to analyse all outcome measures on an intention‐to‐treat basis by including data from all participants.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The heterogeneity among the eligible studies was quantified using the Chi² test and I² statistic, specifically using the formula I² = (Q ‐ df/Q) X 100% where Q was the Chi² statistic and df represented the degree of freedom. The I² statistic values were interpreted as follows:

0% to 25% = low heterogeneity;

25% to 75% = moderate heterogeneity;

more than 75% = substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

We planned to perform a further investigation based on the pre‐specified subgroup analysis where substantial heterogeneity was detected, according to the criteria above.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to explore publication bias through the use of funnel plots and to explore the presence of time‐lag bias in both published and unpublished trials if sufficient eligible trials had been available. As a result of the small number of included studies (five RCTs), these analyses were not performed.

Data synthesis

We performed data synthesis using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). After assessing heterogeneity, we had planned to use a random‐effects model of meta‐analysis if substantial heterogeneity between studies was detected. A fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis was planned if the studies estimated the same intervention effect and had low or moderate heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform subgroup analyses according to the following features if sufficient information had been available:

tobacco exposure (cigarette, cannabis, or any other form of smoking, either measured in a laboratory or declared) after the intervention;

severity of the ischaemia, according to the Fontaine or Rutherford classification;

different doses of the pharmacological agents.

Sensitivity analysis

We had intended to perform sensitivity analyses by looking separately at sponsored studies and publication bias, and by excluding studies with low and moderate methodological quality according to the 'Risk of bias' judgements. As a result of the small number of studies included for each comparison and a meta‐analysis with only two studies, sensitivity analyses were not performed.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main findings of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. We included judgements for the certainty of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data for the primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) according to Higgins 2011 and the GRADE Working group (Atkins 2004). Since we assessed different intervention comparisons, a 'Summary of findings' table was developed for each comparison included in the Results section: (Oral or intravenous) prostanoid versus aspirin for treatment of Buerger's disease (Table 1); Intravenous prostacyclin analogue versus intravenous prostaglandin analogue for treatment of Buerger's disease (Table 2); (Oral or intravenous) prostanoid versus placebo for treatment of Buerger's disease (Table 3); and Any pharmacological agent versus placebo or any other pharmacological agent for treatment of Buerger's disease (Table 4). We used GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015), to assist in the preparation of the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Summary of findings 1. (Oral or intravenous) prostanoid versus aspirin treatment for Buerger's disease.

| Intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus oral aspirin for treatment of Buerger's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with Buerger's disease Settings: hospital and community Intervention: intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) Comparison: oral aspirin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects * (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with oral aspirin | Risk with intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) | |||||

|

Ulcer healing Follow‐up: 28 days |

Study population (28 days) | RR 2.65 (1.15 to 6.11) | 98 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 130 per 1000 |

346 per 1000 (150 to 797) |

|||||

|

Complete relief of rest pain Follow‐up: 28 days |

Study population | RR 2.28 (1.48 to 3.52) | 133 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 277 per 1000 |

631 per 1000 (410 to 975) |

|||||

|

Rate of amputation Follow‐up: 6 months |

Study population | RR 0.32 (0.09 to 1.15) | 95 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 182 per 1000 |

58 per 1000 (16 to 209) |

|||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 one single study (doubt about reproducibility of data), downgraded by one level 2 conflict of interest not stated but it was not considered sufficient to downgrade the certainty of evidence

Summary of findings 2. Intravenous prostacyclin analogue versus intravenous prostaglandin analogue for treatment of Buerger's disease.

| Intravenous prostacyclin analogue versus intravenous prostaglandin analogue for treatment of Buerger's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with Buerger's disease Settings: hospital and community Intervention: intravenous prostacyclin analogue (clinprost, iloprost) Comparison: intravenous prostaglandin analogue (alprostadil) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects * (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with intravenous prostaglandin analogue (alprostadil) | Risk with intravenous prostacyclin analogue (clinprost, iloprost) | |||||

|

Ulcer healing Follow‐up: 28 days |

Study population | RR 1.13 (0.76 to 1.69) | 89 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1,2,3,4 very low | ||

| 480 per 1000 |

542 per 1000 (365 to 811) |

|||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 486 per 1000 | 550 per 1000 (370 to 822) | |||||

|

Complete relief of pain Follow‐up: 28 days |

Study population | RR 1.57 (0.72 to 3.44) | 38 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝2,3,5 low | ||

| 318 per 1000 |

500 per 1000 (229 to 1000) |

|||||

|

Rate of amputation Follow‐up: 28 days |

see comment | ‐ | Rate of amputation was not appraised by the studies in this comparison | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 adoption of 'as‐treated' (per‐protocol) analyses, downgraded by one level 2 absence of patients' smoking history, downgraded by one level 3 conflict of interest not stated but it was not considered sufficient to downgrade the certainty of evidence 4 small number of participants, downgraded by one level 5 one single study (doubt about reproducibility of data), downgraded by one level

Summary of findings 3. (Oral or intravenous) prostanoid versus placebo for treatment of Buerger's disease.

| Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo for treatment of Buerger's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with Buerger's disease Settings: hospital and community Intervention: oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) in two doses: 200 mcg and 400 mcg Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects * (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) | |||||

|

Ulcer healing Follow‐up: 8 weeks |

Study population (200 mcg) | RR 1.11 (0.54 to 2.29) | 133 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 171 per 1000 |

190 per 1000 (93 to 393) |

|||||

| Study population (400 mcg) | RR 0.90 (0.42 to 1.93) | 135 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | |||

| 171 per 1000 |

154 per 1000 (72 to 331) |

|||||

|

Complete relief of rest pain Follow‐up: 8 weeks |

Study population (200 mcg) | RR 1.14 (0.79 to 1.63) | 207 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 343 per 1000 |

391 per 1000 (271 to 559) |

|||||

| Study population (400 mcg) | RR 1.11 (0.77 to 1.59) | 210 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | |||

| 343 per 1000 |

381 per 1000 (264 to 546) |

|||||

|

Rate of amputation Follow‐up: 6 months |

Study population (200 mcg) | RR 0.54 (0.19 to 1.56) | 209 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | ||

| 87 per 1000 |

47 per 1000 (17 to 136) |

|||||

| Study population (400 mcg) | RR 0.42 (0.13 to 1.31) | 213 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝1,2 moderate | |||

| 87 per 1000 |

37 per 1000 (11 to 114) |

|||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 one single study (doubt about reproducibility of data), downgraded by one level 2 conflict of interest not stated but it was not considered sufficient to downgrade the certainty of evidence

Summary of findings 4. Any pharmacological agent versus placebo or any other pharmacological agent for treatment of Buerger's disease.

| Folic acid versus placebo for treatment of Buerger's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with Buerger's disease

Settings: community

Intervention: folic acid Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects * (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with folic acid | |||||

| Ulcer healing | see comment | ‐ | Ulcer healing was not appraised by the study in this comparison | |||

|

Pain

VAS. Scale from: 0 to 10; higher score = more pain Follow‐up: 0, 2, 6 months |

Baseline | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 very low | ||

| The mean pain in the placebo group was 5.09 points | The mean pain in the intervention group was 1.17 higher (0.66 lower to 3.00 higher) | |||||

| 2 months | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 very low | |||

| The mean pain in the placebo group was 5.75 points | The mean pain in the intervention group was 0.3 lower (2.04 lower to 1.44 higher) | |||||

| 6 months | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 very low | |||

| The mean pain in the placebo group was 4.82 points | The mean pain in the intervention group was 1.36 lower (3.17 lower to 0.45 higher) | |||||

|

Change in rate of amputation (Difference in number of amputations at start of treatment) Follow‐up: 2 and 6 months |

2 months | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 very low | No new cases of amputations two months after start of treatment | |

| see comment | ||||||

| 6 months | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝1 very low | No new cases of amputations six months after start of treatment | ||

| see comment | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 participants without critical ischaemia, resulting in absence of amputations and no differences in pain score in both groups, one single small study ‐ downgraded by three levels

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

Results of the search

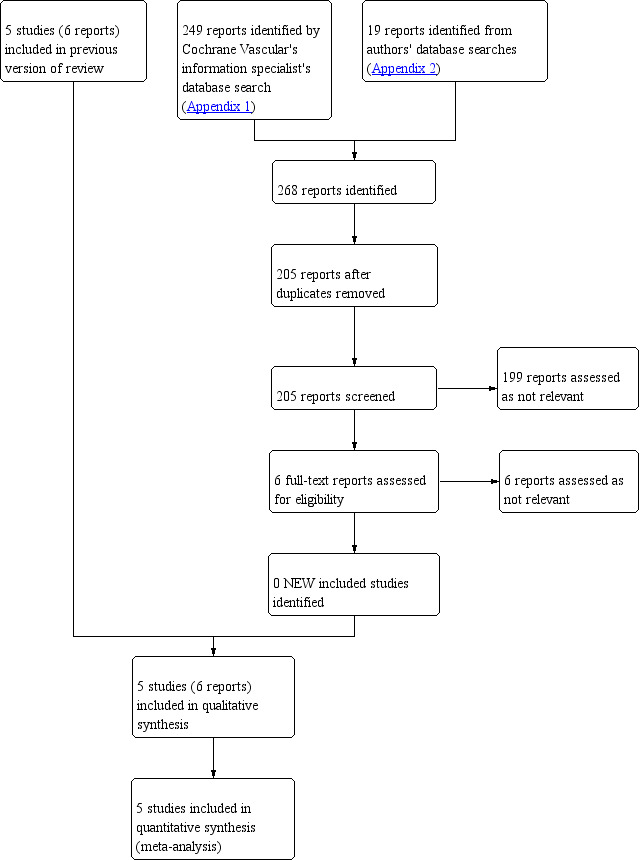

A flow diagram of the search results is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No new studies were identified for this update. Five randomised controlled studies were included in this review, with a combined total of 602 participants (Beigi 2014; Esato 1995; Fiessinger 1990; Ishitobi 1991; Verstraete 1998).

Beigi 2014 reported on a study of 30 participants with Buerger's disease (Fontaine II of ischaemia) and hyperhomocysteinaemia (a well known and established risk factor for limb ischaemia in patients with atherosclerosis), who were receiving folic acid or placebo (single dose); they compared the number of major and minor amputations and pain in both groups.

In Esato 1995, 46 participants with Buerger's disease received a prostacyclin analogue (clinprost) or a prostaglandin analogue (alprostadil) for four weeks; they compared improvements in ischaemic ulcers and rest pain.

Fiessinger 1990 reported on a European multicentre randomised study that included 152 participants with Buerger's disease, in critical limb ischaemia (rest pain, ulcers or gangrene), who were receiving prostacyclin analogue (iloprost endovenously) or aspirin orally for 28 days.

Ishitobi 1991 was a trial of 134 participants with critical limb ischaemia, which included 55 participants diagnosed with Buerger's disease. The pharmacological treatment assessed the efficacy between a prostaglandin analogue (alprostadil) and a prostacyclin analogue (iloprost), both of them administered intravenously for 28 days.

Verstraete 1998 described a large multicentre randomised trial with 319 participants with Buerger's disease with rest pain, ischaemic ulcers, or both, who were administered a prostaglandin analogue (iloprost) orally or placebo for eight weeks, with a six‐month follow‐up.

No studies were identified that compared oral prostanoid and intravenous prostanoid, (oral or intravenous) prostanoid (e.g. iloprost) and cilostazol, aspirin and placebo, cilostazol and placebo, and aspirin and cilostazol.

Excluded studies

Ten studies were excluded (Bozkurt 2006; Coscia 1972; He 2007; Hoshino 1997; Musial 1986; Reichert 1975; Steinorth 1967; Sun 1993; Yang 2005; Zelikovsky 1973). The reasons for exclusion are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. In brief, the main reasons for exclusion were interventions with no pharmacological agents (e.g. acupuncture, sympathectomy; Bozkurt 2006; He 2007; Sun 1993; Yang 2005), studies without patients with Buerger's disease (Steinorth 1967), non‐randomised (Reichert 1975), or participants with mixed diagnoses without a separate description of the outcomes for participants with Buerger's disease (Coscia 1972; Zelikovsky 1973). Musial 1986 assessed an outcome (fibrinolytic activity) not relevant for the review. Hoshino 1997 was classed as an ongoing study in the previous version of the review. As we were unable to locate the full text and determine if it was randomised we have now excluded this study.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a graphical summary of methodological quality for the included studies, based on the 'Risk of bias' domains.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Four included studies (Esato 1995; Fiessinger 1990; Ishitobi 1991; Verstraete 1998), did not describe the method of randomisation and therefore, were classed as unclear risk of bias. Only Beigi 2014, after contact with study authors, was classed as low risk of bias because the trialists used a computerised randomisation method.

Allocation concealment was only reported in the Fiessinger 1990 study, which reported the utilization of a centre of randomisation. Beigi 2014, after contact with study authors, described a method of allocation concealment based on computerised codes that were in the possession of a third person (not involved in drug administration or outcome assessment). The remaining three studies (Esato 1995; Ishitobi 1991; Verstraete 1998) were classified as unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

All five included studies were blinded for performance bias. Beigi 2014, Esato 1995 and Fiessinger 1990 were blinded for detection bias; however, Ishitobi 1991 and Verstraete 1998 did not report whether the outcome evaluators were blinded and so were at unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Beigi 2014 described a study without losses to follow‐up. Follow‐up was available to six months and so were at low risk of attrition bias.

Esato 1995 reported they used intention‐to‐treat analyses, but in practice, adopted 'as‐treated' (per protocol) analyses. All exclusions were explained. Follow‐up was available to four weeks. We judged this study to be at high risk of attrition bias.

Fiessinger 1990 reported by intention‐to‐treat, and justified all the post‐randomisation exclusions. Follow‐up was available to six months. Fiessinger 1990 was therefore judged to be at low risk of attrition bias.

In Ishitobi 1991, the authors did not clearly describe the losses to follow‐up, declaring only that there were more losses in the iloprost group, but not reporting how many participants and possible reasons. Follow‐up was available to four weeks. Ishitobi 1991 was judged to be of high risk of attrition bias.

Verstraete 1998 also reported by intention‐to‐treat, and justified all the post randomisation exclusions. Follow‐up was available to six months. Therefore, Verstraete 1998 was judged to be at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Esato 1995, Ishitobi 1991, and Verstraete 1998 described all outcomes and were judged to be at low risk of reporting bias. Beigi 2014 did not describe the presence of rest pain or ischaemic ulcers and was judged to be at high risk of reporting bias. In Fiessinger 1990, there was conflicting data about the number of patients with ulcers healed after treatment (day 28), and uncertain data about number of patients with ulcers healed after six months of follow up. We judged this study to be at unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In Esato 1995 and Ishitobi 1991, the study authors did not describe tobacco exposure before and after the treatment and both were judged to be at high risk of other bias. Beigi 2014 was judged to be at high risk of other bias because participants without critical ischaemia were eligible, resulting in low chances to be amputated. Verstraete 1998 was judged to be at unclear risk of bias because there was no information about any potential conflict of interest. Fiessinger 1990 was judged to be at low risk of bias because the proportion of smokers and non‐smokers in the study arms at the beginning and after treatment were described.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

(Oral or intravenous) prostanoid (e.g. iloprost) versus aspirin

Intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus oral aspirin

One study assessed this comparison (Fiessinger 1990).

Ulcer healing

Ulcer healing was assessed at the end of treatment (day 28) and six months after the start of treatment. Complete healing of all ulcers, assessed by an independent evaluator, in the iloprost group was 35% (18/52 patients) compared to 13% (6/46 patients) in the aspirin group at day 28 (RR 2.65; 95% CI 1.15 to 6.11; P = 0.02; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). We are unclear over the percentage of people who were followed up to six months who had ulcers. It is possible that of the people followed up at six months, some did not have ulcers. The authors describe the results as follows: "14 of 18 patients who achieved complete healing of trophic changes on iloprost treatment were observed at six months, 13 of whom were still completely healed. Three of the five patients who achieved complete healing of trophic changes on aspirin treatment were observed at six months, and were still completely healed".

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus oral aspirin, Outcome 1: Ulcer healing (4 weeks)

Pain

Pain was assessed at the end of treatment (day 28). Total relief of rest pain in the iloprost group was 63% (43/68 participants) compared to 28% (18/65 participants) in the aspirin group (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.48 to 3.52; P = 0.0002; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus oral aspirin, Outcome 2: Complete relief of rest pain (4 weeks)

Rate of amputation

Rate of amputation: Six months after the start of treatment, three participants treated with iloprost and eight treated with aspirin required major amputation (RR 0.32; 95% CI 0.09 to 1.15; P = 0.08; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intravenous prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus oral aspirin, Outcome 3: Rate of amputation

Side effects

Side effects including headache, flushing, nausea, and abdominal cramps were more common in participants treated with iloprost, but according to the study authors, no participant in either group had to be withdrawn because of side‐effects.

The remaining secondary outcomes of amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking, and ankle brachial index were not assessed by Fiessinger 1990.

Intravenous prostacyclin analogue versus intravenous prostaglandin analogue

Two studies assessed this comparison (Esato 1995; Ishitobi 1991). Esato 1995 compared intravenous prostacyclin analogue clinprost to intravenous prostaglandin analogue alprostadil. Ishitobi 1991 compared intravenous prostacyclin analogue iloprost to intravenous prostaglandin analogue alprostadil.

Ulcer healing

Esato 1995 assessed ulcer healing at the end of treatment (4 weeks). Ulcer healing was evaluated by an assistant doctor (a medical researcher responsible for recruiting and outcome evaluation) using metric parameters (ulcer size), presence of granulation tissue and infection status. Improvement of ischaemic ulcers were seen in 70.6% (12/17 participants) in the clinprost group compared to 56.5% (13/23) in the alprostadil group (RR 1.25, 95% of CI 0.78 to 2.00; P = 0.36). Total recuperation was seen in 23.5% (4/17 patients) in the clinprost group compared to 8.7% (2/23 participants) in the alprostadil group (RR 2.38, 95% of CI 0.48 to 11.7).

Ishitobi 1991 assessed ulcer healing at the end of treatment (day 28). Ulcer healing was assessed by an assistant doctor and was evaluated with metric parameters (ulcer size), presence of granulation tissue, and presence or absence of infection. Posteriorly classified as ulcer healing improvement in Buerger's subgroups, the iloprost group reported 41% (9/22 patients) compared to 41% (11/27) in the alprostadil group (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.98).

Ulcer healing data (improvement of ischaemic ulcers) from Esato 1995 and Ishitobi 1991 were pooled and showed no clear difference between the treatment groups (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.69; 89 participants; 2 studies; P = 0.54; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1; Esato 1995; Ishitobi 1991).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prostacyclin versus prostaglandin E1, Outcome 1: Ulcer healing

Pain

Esato 1995 assessed pain at the end of treatment (four weeks). Pain was evaluated by an assistant doctor. Fifty percent (8/16 participants) of the clinprost group were free of pain compared with 31.8% of the alprostadil group (7/22 patients; RR 1.57; 95% CI 0.72 to 3.44; P = 0.26; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Prostacyclin versus prostaglandin E1, Outcome 2: Complete relief of pain

In Ishitobi 1991, pain was not measured with a validated score or scale, or a quality of life questionnaire. Pain was assessed using five levels (1 = much better, 2 = better, 3 = little better, 4 = no difference, and 5 = worse). Participants in the iloprost group reported pain as: much better = 21.7% (5/23 patients), better = 34.8% (8/23 patients), little better = 17.4% (4/23 patients), no difference = 21.7% (5/23 patients), and worse = 4.4% (1/23 patients). Participants in the alprostadil group reported pain as: much better = 28.5% (8/28 patients), better = 32.1% (9/28 patients), little better = 14.3 % (4/28 patients), no difference = 21.5% (6/28 patients), and worse = 3.6% (1/28 patients). Ishitobi 1991 reported that this finding was not statistically significant.

Rate of amputation

Rate of amputation was not appraised by Esato 1995 or Ishitobi 1991.

Side effects

Esato 1995 reported that five participants in the clinprost group and two participants in the alprostadil group experienced side effects. In the clinprost group, one participant developed nausea, tinnitus and vertigo in the third week of drug administration, without serious repercussion; another three participants had modification of blood tests relating to liver function, but without further repercussions after the drug administration was ceased, and one participant developed limb edema, probably not related to the clinprost use. The alprostadil group had one participant with modification in blood tests relating to liver function, but also without further repercussions after the drug administration was ceased, and another participant experienced a heat sensation in the head, only on the first day of treatment.

Side effects were not clearly specified in Ishitobi 1991 for patients with Buerger's disease. Overall, 13 participants (17.3%) in the iloprost group and 11 participants (13.9%) in the alprostadil group experienced side effects, such as headache, vomiting, and flushing.

The remaining secondary outcomes of amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking, and ankle brachial index were not appraised by Esato 1995 or Ishitobi 1991.

(Oral or intravenous) prostanoid versus placebo

Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo

One study assessed this comparison (Verstraete 1998).

Ulcer healing

Ulcer healing was assessed at the end of treatment (eight weeks) and six months after the start of treatment. After eight weeks (end of treatment), complete healing of all ulcers was 19% in the 200 mcg iloprost group (12/63 participants; RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.54 to 2.29; P = 0.78; moderate‐certainty evidence), 15% in the 400 mcg iloprost group (10/65 participants; RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.93; P = 0.78; moderate‐certainty evidence), and 17% in the placebo group (12/70 participants; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2). After six months, the 200 mcg iloprost group reported complete healing of all ulcers in 49% (31/63 participants; RR 1.19; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.73; P = 0.37; moderate‐certainty evidence), the 400 mcg iloprost group reported 41% (27/65 participants; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.50; P = 0.99; moderate‐certainty evidence), and the placebo group reported 41% (29/70 participants) complete healing of all ulcers (Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 1: Ulcer healing (8 weeks) ‐ iloprost 200 mcg

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 2: Ulcer healing (8 weeks) ‐ iloprost 400 mcg

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 3: Ulcer healing (6 months) ‐ iloprost 200 mcg

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 4: Ulcer healing (6 months) ‐ iloprost 400 mcg

Verstraete 1998 also reported improvement of the most important ulcer (improved healing was not a defined outcome in this review): improvement of the most important ulcer was 55% in the 200 mcg iloprost group (P = 0.056 versus placebo), 63% in the 400 mcg iloprost group (P = 0.008 versus placebo), and 40% in the placebo group after eight weeks (end of treatment). After six months, the 200 mcg iloprost group reported improvement of the most important ulcer in 84% (P = 0.007 versus placebo), the 400 mcg iloprost group reported improvement in 68% (P = 0.297 versus placebo), and the placebo group reported improvement in 62%.

Pain

Pain was assessed at the end of treatment (eight weeks) and six months after the start of treatment. After eight weeks (end of treatment), complete relief of rest pain was 39% in the 200 mcg iloprost group (41/105 participants; RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.63; P = 0.48; moderate‐certainty evidence), 38% in the 400 mcg iloprost group (41/108 participants; RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.59; P = 0.58, moderate‐certainty evidence), and 34% in the placebo group (35/102 participants; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6). After six months, the 200 mcg iloprost group reported complete relief of rest pain in 63% (66/105 participants; RR 1.28; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.64; P = 0.05; low‐certainty evidence), the 400 mcg iloprost group reported 49% (53/108 participants; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.32; P = 0.99; moderate‐certainty evidence), and the placebo group reported 49% (50/102 participants) complete relief of rest pain (Analysis 3.7; Analysis 3.8).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 5: Complete relief of rest pain (8 weeks) ‐ iloprost 200 mcg

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 6: Complete relief of rest pain (8 weeks) ‐ iloprost 400 mcg

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 7: Complete relief of rest pain (6 months) ‐ iloprost 200 mcg

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 8: Complete relief of rest pain (6 months) ‐ iloprost 400 mcg

Rate of amputation

Rate of amputation was assessed at six months after the start of treatment: the placebo group reported 9% major amputations (9/103 participants), the 200 mcg iloprost group reported 4.7% major amputations (5/106 participants; RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.19 to 1.56; P = 0.25; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.9), and the 400 mcg iloprost group reported 3.6% major amputations (4/110 participants; RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.31; P = 0.13; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.10).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 9: Rate of amputation ‐ iloprost 200 mcg

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo, Outcome 10: Rate of amputation ‐ iloprost 400 mcg

Side effects

Participants in the 400 mcg iloprost group developed about 25% more (68%) side effects than participants in the 200 mcg iloprost group (43%) and the placebo group (38%). According to the study authors, the most frequent side effect reported was headache (more than 20%), followed by vasodilatation and trismus (the latter two cases for the high‐dose iloprost group only).

The remaining secondary outcomes of amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking, and ankle brachial index were not assessed by Verstraete 1998.

Any pharmacological agent versus placebo or any other pharmacological agent

Folic acid versus placebo

One study assessed this comparison (Beigi 2014).

Ulcer healing

Ulcer healing was not evaluated by Beigi 2014.

Pain assessment

Pain was assessed at baseline, two months and six months, using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), a continuous scale, ranging from 0 to 10, where a higher score means more pain. At baseline, the mean VAS score in the folic acid group was 7.07 points (SD 2.82), and the placebo group was 5.9 points (SD 2.21), resulting in MD 1.17; CI ‐0.66 to 3.00; P = 0.21; very low‐certainty evidence. At two months, the folic acid group was 5.45 points (SD 2.75), and the placebo group was 5.75 points (SD 1.99) resulting in MD ‐0.30; CI ‐2.04 to 1.44; P = 0.74, very low‐certainty evidence. After six months, the folic acid group was 3.46 points (SD 2.57), and the placebo group was 4.82 points (SD 2.46), resulting in MD ‐1.36; CI ‐3.17 to 0.45; P = 0.14, very low‐certainty evidence. (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Folic acid versus placebo, Outcome 1: Pain (0 month)

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Folic acid versus placebo, Outcome 2: Pain (2 months)

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Folic acid versus placebo, Outcome 3: Pain (6 months)

Rate of amputation

Rate of amputation was assessed at baseline, two months, and six months after the beginning of treatment. At baseline, five participants (5/14) in the folic acid group and four participants (4/16) in the placebo group had minor amputations; one participant (1/14) in the folic acid group and none of the participants in the placebo group had a major amputation. There was no change in the number of participants with amputations during the entire study; that is, at two months and six months, no new cases of major or minor amputation were observed very low‐certainty evidence. According to the study authors, the differences between the folic acid and placebo groups were not statistically significant (Analysis 4.4; Analysis 4.5).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Folic acid versus placebo, Outcome 4: Change in rate of amputation (2 months)

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Folic acid versus placebo, Outcome 5: Change in rate of amputation (6 months)

Side effects

No side effects were reported.

The remaining secondary outcomes of amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking, and ankle brachial index were not assessed by Beigi 2014.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The five included studies evaluated 602 participants and appraised the efficacy of prostacyclin or prostaglandin analogues against another drug or placebo, in patients with Buerger's disease. Folic acid was also evaluated against placebo in one more recent study.

Prostacyclin analogue iloprost, intravenously administered, was effective in healing ulcers and eradicating rest pain after 28 days of treatment, when compared with aspirin (moderate‐certainty evidence). However, this evidence was restricted to a single study (133 participants), and consequently, the reproducibility of results is questionable.

Equivalent efficacy was discovered between prostacyclin (iloprost and clinprost) and prostaglandin (alprostadil) analogues as analysed by two studies, when evaluating ulcer healing (very low‐certainty evidence), and rest pain resolution after 28 days of treatment (low‐certainty evidence).

Oral prostacyclin analogue iloprost was not effective in healing ischaemic ulcers (moderate‐certainty evidence), or eradicating rest pain (moderate‐certainty evidence), when measured at the end of treatment and six months later, when compared with placebo. Evidence related to efficacy about rest pain resolution after six months of treatment with iloprost 200 mcg was inconsistent with a dose‐response relationship, and the magnitude of the effect observed was low (RR 1.28; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.64; (low‐certainty evidence); thus, the evidence is questionable.

In patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia, folic acid, when compared with placebo, did not demonstrate a protective effect against amputations, because there was an absence of amputations in both groups (very low‐certainty evidence). Another outcome presented was pain; results found no clear differences between the groups (very low‐certainty evidence). However, the participants chosen were classed as Fontaine II; in other words, they did not have rest pain.

In most cases, treatment side effects experienced by the participants, such as headaches, flushing, or nausea, did not lead to treatment interruptions or more serious consequences. None of the included studies assessed amputation‐free survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking distance, or ankle brachial index.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The main objective of this review was to assess the effectiveness of the pharmacological agents administered in patients with Buerger’s disease at different stages of ischaemia. However, we identified only a small number of studies (five randomised controlled trials) with patients of more severe stages of the disease (ulcers, rest pain, or both). In fact, more severe cases of Buerger’s disease are often treated with therapies for limb ischaemia, such as sympathectomy and pharmacological treatment, rather than limb revascularisation.

Interventions in the five studies were limited to evaluating prostaglandin and prostacyclin analogues, and folic acid, and did not evaluate other pharmacological agents such as cilostazol, clopidogrel, and pentoxifylline versus placebo or each other.

Another important issue concerns the period of treatment. This was limited to four or eight weeks in the included studies. Perhaps prolonged administration until, for example, complete healing or total relief of rest pain, could improve the success of the treatment.

Evidence suggested that iloprost, given intravenously, was more effective than aspirin in healing ischaemic ulcers and eradicating rest pain. This evidence was generated with an interesting comparative i.e. aspirin; patients with severe Buerger’s disease with limited treatment options are often treated as patients with atherosclerotic aetiology.

Outcomes measured in the studies were limited to assessments of ulcer healing and pain. Particularly problematic was pain evaluation. No study used a validated pain score or scale, or quality of life questionnaires, and consequently, more detailed assessments of pain was not possible. Amputation free‐survival, walking distance or pain‐free walking, and ankle brachial index were not assessed in any of the included studies.

Very‐low certainty evidence suggested that folic acid did not provide a protective effect against amputations and rest pain in patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia. Therefore, routine folic acid administration in patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia remains questionable.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the certainty of the evidence was very low to moderate, with few studies, a small number of participants and potential for biases such as randomisation and allocation concealment methods.

We have summarised the certainty of the evidence for the main comparisons below:

Intravenous prostacyclin analogue iloprost versus oral aspirin

See Table 1. Classified as moderate‐certainty evidence. The evidence was obtained from a randomised controlled trial, with low risk of bias, and showed a large magnitude of effect (RR > 2.0). However, just one study was available for this comparison and additional data about reproducibility of the outcomes were not available, therefore we downgraded by one step due to imprecision.

Intravenous prostacyclin analogue versus intravenous prostaglandin analogue

See Table 2. Classified as low and very low‐certainty evidence. The evidence was obtained from two randomised controlled trials, which were double‐blinded and demonstrated low heterogeneity, but the evidence was downgraded because a small number of participants was evaluated, and most importantly, the proportion of tobacco exposure between groups, and before the start of treatment was not described. In addition, 'as‐treated' (per‐protocol) analyses were adopted further downgrading the certainty of evidence for ulcer healing.

Oral prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) versus placebo

See Table 3. Classified as moderate and low‐certainty evidence. The evidence was obtained from a randomised controlled trial, with overall low risk of bias. However, just one study was available for this comparison and additional data about reproducibility of the outcomes were not available. In addition, evidence suggesting relief of rest pain was found with low dose of iloprost (200 mcg) but not with high dose of iloprost (400 mcg), demonstrating absence of a dose‐response effect and, consequently, downgrading the certainty of the evidence for relief of rest pain after six months to low.

Folic acid versus placebo

See Table 4. Classified as very low‐certainty of evidence. One study with a small number of participants was available for this comparison and additional data about reproducibility of the outcomes were not available. In addition, participants without critical ischaemia were recruited into the trial, resulting in the absence of amputations and no differences in pain score in both groups.

Potential biases in the review process

The study of Hoshino 1997 which assessed the efficacy of pamicogrel (antiplatelet drug) in patients with Buerger's disease, was not included in this review because a full report was not available. Thus, a potential pharmacological agent was not evaluated. Another potential bias relates to pain assessment. For the evaluation of the treatment effect on pain, we only considered absence or presence of pain in the included studies, because none of the included studies used a validated pain scale or score for appropriate assessment.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We did not identify any other systematic reviews about the pharmacological treatment for Buerger’s disease.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that intravenous iloprost (prostacyclin analogue) is more effective than aspirin for eradicating rest pain and healing ischaemic ulcers in Buerger’s disease, but oral iloprost is not more effective than placebo.

Very low and low‐certainty evidence suggests there is no clear difference between prostacyclin (iloprost and clinprost) and the prostaglandin analogue alprostadil for healing ulcers and relieving pain respectively in severe Buerger’s disease.

Very low‐certainty evidence suggests there is no clear difference in pain and rates of amputation between folic acid and placebo in patients with Buerger's disease and hyperhomocysteinaemia.

In most cases, treatment side effects such as headaches, flushing or nausea experienced by the participants were not associated with treatment interruptions or more serious consequences.

Implications for research.

Further well designed RCTs assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological agents (intravenous or oral) in people with Buerger's disease are needed. We suggest future trials investigating pharmacological treatment of Buerger’s disease should incorporate the following characteristics:

Clearly describe the methods of randomisation and concealment of allocation;

Include participants with mild/moderate ischaemia, such as intermittent claudication;

Evaluate outcomes, such as walking distance, pain–free walking distance and ankle brachial index;

Compare prostacyclin versus prostaglandin analogues;

Investigate pharmacological agents for which there currently is no RCT evidence such as pentoxifylline, cilostazol and clopidogrel;

Assess pain utilizing validated scores/scales;

Assess quality of life using quality of life scales;

Evaluate time without amputation (amputation free‐survival);

Investigate folic acid reposition in patients with Buerger's disease, hyperhomocysteinaemia and critical limb ischaemia.

Feedback

Quality of evidence, February 2016

Summary

Comment: You say that: "Compared with aspirin, intravenous prostacyclin analogue iloprost improved ulcer healing (risk ratio (RR) 2.65; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 6.11; 98 participants; one study; moderate quality evidence), and helped to eradicate rest pain after 28 days (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.48 to 3.52; 133 participants; one study; moderate quality evidence)".

For ulcer healing the data are from Analysis 2.1, from a single study done 25 years ago. It showed 18/52 with iloprost and 6/46 with aspirin. The definition of moderate evidence is that "further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate”. Quite right, and here I repeated the analysis with a single misclassification error simulated, so that the numbers were 17/52 vs 7/46. The relative risk then became 2.15 (0.98 to 4.72). In other words, not significant, with results from a single patient changed.

Fiessinger 1990 has no data on 4‐week ulcer healing, and so far as I can see there is no explanation from whence these numbers are derived. Nor is any reason given as to why the denominators in the calculations are different from both the numbers randomised (68 and 65) or those followed in the longer term (51 and 44).

Some points.

1: Fiessinger 1990 gives a beautiful explanation of a double‐blind double dummy method, and while it is low risk, a simple statement of double blind is insufficient given that one treatment is an infusion and the other a tablet.

2: There is no explanation of where the numbers come from.

3: And given the very considerable literature concerning the dangers of doing sums on small numbers of patients and events, surely the true answer for ulcer healing here is that we just don't know. If one patient can make a difference between significant to not significant, then surely the quality of the evidence is very low. And that is at best. Almost all statistical results here derive from small numbers of participants and events from single studies. The reality is that we can't know given the paucity of data available.

Personally, I think that the GRADE system, with three categories where one might expect results to be altered, is the real problem. Moderate quality sounds good, but the definition of moderate that "further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate" is no different from low. Very low quality is the preserve of very small numbers, as here.

Reply

Thank you for your comments. Answering your observations: 1) Participants in both groups received an injectable solution and a tablet. In the intervention group, a injectable solution containing iloprost and placebo tablet was administrated and, in turn, in the control group an injectable placebo solution and an aspirin tablet was administered. We have amended the description of the performance bias domain in the Risk of Bias table with this information; 2) Fiessinger 1990 wrote "Of the other 133 patients, 98 also had ulcer leg". So, 35 participants had only rest pain, and 98 participants had rest pain and leg ulcer (52 participants in iloprost group and 46 in aspirin group = 98 participants for which ulcer healing could be assessed). The total number of participants (68 and 65) was evaluated only for the study outcome "responders" and total relief of rest pain. Indeed, after six months from start of treatment a large number of participants were lost (29%). No explanation of reasons for loss to follow‐up was provided. In response to this comment we have revisited the original article and have now presented the data for ulcer healing at six months narratively within the results section. We have also reassessed the risk of reporting bias for this study from low to unclear. 3) We used the GRADE system as a guide for the assessment of the certainty of evidence in this review. We began by considering the evidence as high (because it was generated by a randomised controlled trial). After that, we evaluated possible factors that downgraded the certainty of the evidence. Certainty of the evidence was diminished to a degree by failure in one of the five questions of the GRADE approach: imprecision of the results. The imprecision demonstrated in the study by Fiessinger 1990 and the fact it was not possible to assess reproducibility lowered the certainty of evidence to moderate. Overrating this factor, in our view, is justified only if the study had a weak statistical power, which is not the case.

Contributors

Feedback: Prof Andrew Moore, University of Oxford, Cochrane author and editor I do not have any affiliation with or involvement in any organisation with a financial interest in the subject matter of my comment

Response: Dr Daniel G Cacione on behalf of co‐authors

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 January 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New search run. No new included or excluded studies identified. New author joined the review team. Text updated to reflect current Cochrane standards. Feedback addressed. No change to conclusions. |

| 14 January 2020 | New search has been performed | New search run. No new included or excluded studies identified. |

| 14 January 2020 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback addressed by review authors. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2014 Review first published: Issue 2, 2016

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 February 2016 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback received |

| 3 February 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Author order amended on request of authors |

| 3 February 2016 | Amended | Author order amended on request of authors |

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to thank Cochrane Brazil for their methodological support. Special thanks to the Cochrane Vascular staff (Marlene Stewart, Cathryn Broderick, and Candida Fenton) for all their attention and support. Thanks to Ms Lidia Harumi Ivasa for translating the Japanese articles so competently.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Database searches

| Source | Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| CENTRAL | #1 Buerger*:TI,AB,KY 70 #2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Thromboangiitis Obliterans EXPLODE ALL TREES 16 #3 (thromboang* ADJ2 oblit*):TI,AB,KY 51 #4 (endangitis obliterans):TI,AB,KY 0 #5 Winiwarter:TI,AB,KY 0 #6 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 95 #7 01/01/2015 TO 15/10/2019:CD 741000 #8 #6 AND #7 60 |

60 |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | Buerger OR Buergers or Thromboangiitis Obliterans | 2 |

| ICTRP Search Portal | Buerger OR Buergers or Thromboangiitis Obliterans | 16 |

| Medline (Ovid MEDLINE® Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE® Daily and Ovid MEDLINE®) 1946 to present | 1 Buerger*.ti,ab. 2 exp Thromboangiitis Obliterans/ 3 (thromboang* adj2 oblit*).ti,ab. 4 endangitis obliterans.ti,ab. 5 Winiwarter.ti,ab. 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 7 randomized controlled trial.pt. 8 controlled clinical trial.pt. 9 randomized.ab. 10 placebo.ab. 11 drug therapy.fs. 12 randomly.ab. 13 trial.ab. 14 groups.ab. 15 or/7‐14 16 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 17 15 not 16 18 6 and 17 19 (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018* or 2019*).ed. 20 18 and 19 21 from 20 keep 1‐48 |

48 |