In this short report on the COVID-19 ‘invasion’ of Italy, we will not give the usual list of numbers that are constantly changing and can be easily accessed on television and/or the internet, or from some other recent reports.1–3 Instead, we highlight some relevant dates and some considerations.

The beginning

On 30 January 30 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic officially started in Italy. Two elderly Chinese tourists (husband and wife) visiting Rome tested positive for COVID-19 and were hospitalized at ‘Spallanzani’ Hospital in Rome. On 19 February 2020 the conditions of the first two cases ameliorated. The Chinese Ambassador congratulated the hospital staff. The Italian population was told that COVID-19 affects the elderly, but it is curable. We all felt reassured.

The explosion

The following day, 20 February 2020, a male patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at the Codogno Hospital (Lombardy, Northern Italy) with severe acute respiratory syndrome and was found to be positive for the COVID-19 infection. The Italians remained incredulous: the patient was young and healthy, in his 30s and it was not possible to locate the source of transmission: no contact with China or Chinese nationals. He was labelled as Patient 1.

On 21 February 2020, the positive cases in Codogno increased to 36, with many critically ill without links to Patient 1. Another cluster of COVID-19 patients was simultaneously identified in a village in the nearby Veneto region and another one in Emilia Romagna which borders Lombardy. The same day, an emergency task force was formed by the Government of these three regions, and health authorities were asked to deal with the outbreak.

On 23 February 2020, these geographical areas were locked down. Italians started to become concerned. The number of cases identified rapidly increased, mainly in Northern Italy, but spreading to all regions of the country. The fatality rate also increased.

On 2 March 2020, the entire region of Lombardy was quarantined and compulsory self-isolation measures were introduced. The ICU capacity of the region (normally 720 beds with a usual rate of occupation between 85% and 90%) was almost doubled, with the creation of cohort ICUs for COVID-19. Personal protective equipment and training on how to deal with COVID-19 patients were provided to the hospitals, but not so much to family doctors, a protocol which meant the triage of patients with fever or respiratory symptoms was organized just outside each hospital. Extra healthcare personnel were quickly recruited, non-urgent procedures were cancelled, and a detailed reporting system to the regional and national coordination centres was established. All of this in 2 weeks! The tension among Italians became palpable.

On 9 March 2020, riots in prisons started, leading to seven deaths in Modena and several hospitalizations. Fifty prisoners escaped in Foggia; luckily all except one were re-captured. Linear and/or exponential models started to forecast a huge number of ICU admissions and, in short, it became evident that even the northern healthcare system, the best in the country, was near to collapse. On 10 March 2020, the entire country was quarantined by the Government with stronger self-isolation measures.

On 25 March 2020, following several declarations increasing the restrictions bit by bit, the Government blocked all industrial activities with the exception of those deemed essential.

The situation as of 1 April 2020

Italy is still silent and at home. Several industries have been converted to produce healthcare equipment to assist with the shortage of everything: respiratory equipment, masks, etc. Existing hospitals have been re-organized to become at least 70% COVID-19. The ICU capacity of the country has been quadrupled. In Milan alone, a 700-bed hospital was built in the pavilion of a convention centre in 7 days and others have been moved to hotels. Many other creative emergency hospitals and even field hospitals are on the way all over Italy. A total of 7200 doctors answered a request for 300 hundred needed in Lombardy. Schooling, exams, marriages, and mass are all conducted via streaming; funerals are currently forbidden. The Pope prays online facing a deserted St Peters Square in Rome.

For those who die in hospital during a pandemic, they die alone with no physical contact with loved ones who are kept at a distance for their own protection against the virus. The family left behind has no consolation either as they are not able to see the body or arrange for burial clothes, or indeed attend a burial. In many cities, the number of deaths is higher than the capacity of the funeral directors to arrange a burial or a cremation.

On a more positive note, the pollution has improved, and thefts, burglaries, and murders have become a very rare occurrence. To overcome the stress of isolation, many Italians are still singing together from their windows and, importantly, in the last 4 days, the percentage of contagion and deaths has started to decline.

COVID-19 in Italy vs. the rest of the world

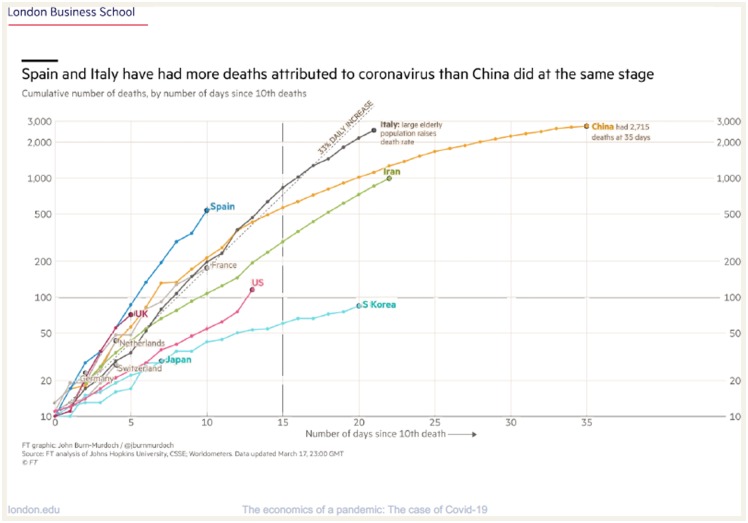

Figure 1 shows an analysis from the Johns Hopkins University updated on 17 March on patterns of contagion in some countries. Italy has the sad record of being the number one country in terms of cases, more even than China. However, the USA has overtaken Italy and China at the time of writing. However, Italy, and now also Spain, has more COVID-19 deaths than China and the USA. The high Italian mortality data require consideration. Global fatality rates are very heterogeneous, with Germany, for instance, reporting fewer fatalities compared with European countries with a similar population.

Figure 1.

The ‘Davide di Donatello’ at the time of the COVID-19 epidemic.

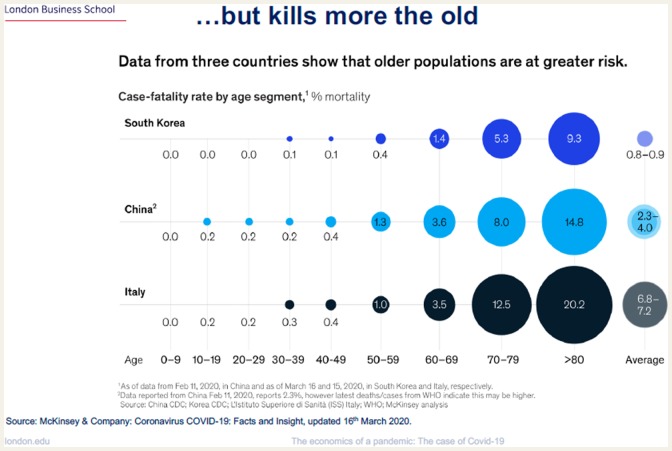

The fatality rate, in contrast to the mortality rate (i.e. the number of deaths/population) refers to the number of deaths/cases. By definition, the fatality rate is imprecise as it is difficult to know the real number of cases in the light of the large number of suspected asymptomatics. The number of cases also depends on the swabs which are taken. In Italy, these were performed only on sick patients; in South Korea at random on the entire population. Thus, the overall Italian fatality rate of 7.2% is grossly overestimated. In addition, COVID-19 affects the population disproportionally: the fatality rate in the elderly population is 3–4 times larger than average; men being more likely to be infected than women. When data were stratified by age group, the case fatality rates in Italy and China are similar, at least for age groups 0–69 years. In South Korea, because of the huge number of tests made, the rates are lower (Figure 2). Italian rates are high for individuals aged 70 years or older and particularly so in people older than 90 who are not even reported in China. It is known that the Italian population is an elderly one and, consequently, at greater risk of being affected by the virus and of dying, because of comorbidities. Another explanation for the high fatality rates relates to how the deaths are identified in Italy. A COVID-19-related death is a death occurring in patients who tested positive for COVID-19 independently from pre-existing diseases that might have caused death. This is because a clear definition of COVID-19 death is not available and defining death is difficult even by expert adjudicator committees of clinical trials! So, Italy is probably overestimating its fatality rate. The young are far more likely to be infected and to become carriers of the disease. This may be another problem for Italy as the family-centred social structure of the country favours frequent contact of the young with the elderly members of the family. It is not easy to give up Sunday lunch with grandparents!

Figure 2.

Data from South Korea, China, and Italy on case fatality rate by age segments (Source London Business School Webinar Series https://www.london.edu/ accessed 28 March 2020).

Apart from these sad thoughts, it is important to describe the considerations of Italy from the rest of the world. Some countries closed their borders, others refused to accept cruise ships with Italians on board, several international newspapers were referring to ‘the usual Italians’ or ‘Italy makes laws that Italians will not respect’. However, when the pandemic started to hit worldwide, these comments radically changed. The majority of the countries are watching and following Italian initiatives, and are importantly sending materials, doctors, nurses, and even hospitals. Today, in many critical hubs, the language is not only Italian but Chinese, American English, Spanish, Russian, etc. Italy is very grateful.

Conclusion

Italy is the first democratic nation to face the worst health crisis of our times.

Undoubtedly, we are still in the middle of the storm but it is no longer a ‘perfect storm’. Italy is still stunned, not only by the direct effects of the virus but also by the measures put in place to defeat it. The social distancing imposed by this pandemic is against Italian culture. Many things went wrong and other things could have been done better. However, we believe that, after all, the government has reacted step by step in a positive way.

As correctly pointed out,3 our health system, like many others, is patient-centred. Epidemics require community-centred care and solutions for the entire population rather than for intensive care, but the intrinsic capacity of the Italians to adapt is working miracles. For once, Italy is first testing a pilot strategy that we hope will work. Other countries should learn from us, taking advantage of our mistakes and, importantly, react now; there is no time to wait and see.

References

References are available as supplementary material at European Heart Journal online.

Roberto Ferrari1,2*, Aldo P. Maggioni3, Luigi Tavazzi2, and Claudio Rapezzi1,2

1Cardiovascular Center, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy; 2Maria Cecilia Hospital, GVM Care&Research, Cotignola (RA), Italy; and 3ANMCO Research Center, Firenze, Italy

* Corresponding author. Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara, Ospedale di Cona, Via Aldo Moro 8, 44124 Cona, Ferrara, Italy. Tel: +39 0532 239882, Fax: +39 0532 237841, Email: fri@unife.it

Supplementary Material

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.