Abstract

Background

Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care is provided by multi‐disciplinary teams that manage stroke patients. This can been provided in a ward dedicated to stroke patients (stroke ward), with a peripatetic stroke team (mobile stroke team), or within a generic disability service (mixed rehabilitation ward). Team members aim to provide co‐ordinated multi‐disciplinary care using standard approaches to manage common post‐stroke problems.

Objectives

• To assess the effects of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care compared with an alternative service.

• To use a network meta‐analysis (NMA) approach to assess different types of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for people admitted to hospital after a stroke (the standard comparator was care in a general ward).

Originally, we conducted this systematic review to clarify:

• The characteristic features of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care?

• Whether organised inpatient (stroke unit) care provide better patient outcomes than alternative forms of care?

• If benefits are apparent across a range of patient groups and across different approaches to delivering organised stroke unit care?

Within the current version, we wished to establish whether previous conclusions were altered by the inclusion of new outcome data from recent trials and further analysis via NMA.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (2 April 2019); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4), in the Cochrane Library (searched 2 April 2019); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 1 April 2019); Embase Ovid (1974 to 1 April 2019); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1982 to 2 April 2019). In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing trials, we searched seven trial registries (2 April 2019). We also performed citation tracking of included studies, checked reference lists of relevant articles, and contacted trialists.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled clinical trials comparing organised inpatient stroke unit care with an alternative service (typically contemporary conventional care), including comparing different types of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for people with stroke who are admitted to hospital.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed eligibility and trial quality. We checked descriptive details and trial data with co‐ordinators of the original trials, assessed risk of bias, and applied GRADE. The primary outcome was poor outcome (death or dependency (Rankin score 3 to 5) or requiring institutional care) at the end of scheduled follow‐up. Secondary outcomes included death, institutional care, dependency, subjective health status, satisfaction, and length of stay. We used direct (pairwise) comparisons to compare organised inpatient (stroke unit) care with an alternative service. We used an NMA to confirm the relative effects of different approaches.

Main results

We included 29 trials (5902 participants) that compared organised inpatient (stroke unit) care with an alternative service: 20 trials (4127 participants) compared organised (stroke unit) care with a general ward, six trials (982 participants) compared different forms of organised (stroke unit) care, and three trials (793 participants) incorporated more than one comparison.

Compared with the alternative service, organised inpatient (stroke unit) care was associated with improved outcomes at the end of scheduled follow‐up (median one year): poor outcome (odds ratio (OR) 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69 to 0.87; moderate‐quality evidence), death (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.88; moderate‐quality evidence), death or institutional care (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.85; moderate‐quality evidence), and death or dependency (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.85; moderate‐quality evidence). Evidence was of very low quality for subjective health status and was not available for patient satisfaction. Analysis of length of stay was complicated by variations in definition and measurement plus substantial statistical heterogeneity (I² = 85%). There was no indication that organised stroke unit care resulted in a longer hospital stay. Sensitivity analyses indicated that observed benefits remained when the analysis was restricted to securely randomised trials that used unequivocally blinded outcome assessment with a fixed period of follow‐up. Outcomes appeared to be independent of patient age, sex, initial stroke severity, stroke type, and duration of follow‐up. When calculated as the absolute risk difference for every 100 participants receiving stroke unit care, this equates to two extra survivors, six more living at home, and six more living independently.

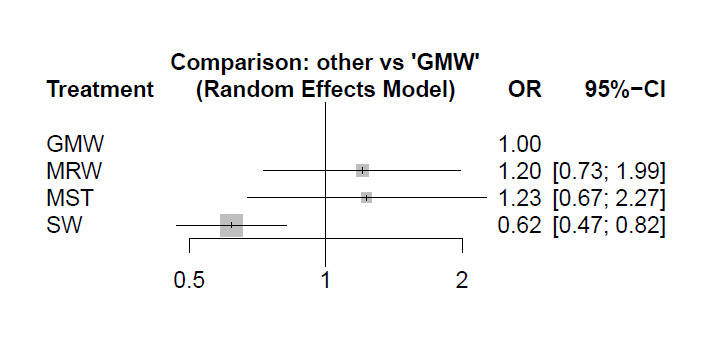

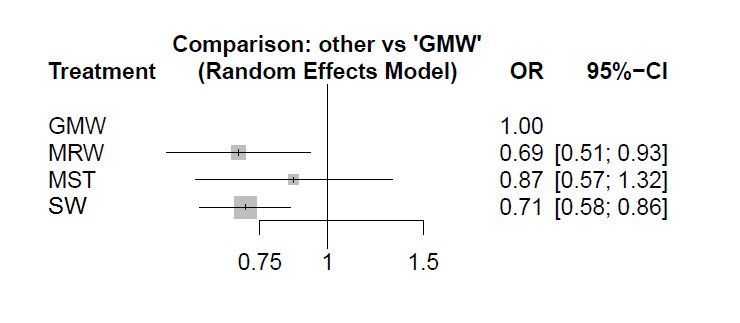

The analysis of different types of organised (stroke unit) care used both direct pairwise comparisons and NMA.

Direct comparison of stroke ward versus general ward: 15 trials (3523 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in general wards. Stroke ward care showed a reduction in the odds of a poor outcome at the end of follow‐up (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91; moderate‐quality evidence).

Direct comparison of mobile stroke team versus general ward: two trials (438 participants) compared care from a mobile stroke team with care in general wards. Stroke team care may result in little difference in the odds of a poor outcome at the end of follow‐up (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.22; low‐quality evidence).

Direct comparison of mixed rehabilitation ward versus general ward: six trials (630 participants) compared care in a mixed rehabilitation ward with care in general wards. Mixed rehabilitation ward care showed a reduction in the odds of a poor outcome at the end of follow‐up (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90; moderate‐quality evidence).

In a NMA using care in a general ward as the comparator, the odds of a poor outcome were as follows: stroke ward ‐ OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.89, moderate‐quality evidence; mobile stroke team ‐ OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.34, low‐quality evidence; mixed rehabilitation ward ‐ OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.95, low‐quality evidence.

Authors' conclusions

We found moderate‐quality evidence that stroke patients who receive organised inpatient (stroke unit) care are more likely to be alive, independent, and living at home one year after the stroke. The apparent benefits were independent of patient age, sex, initial stroke severity, or stroke type, and were most obvious in units based in a discrete stroke ward. We observed no systematic increase in the length of inpatient stay, but these findings had considerable uncertainty.

Keywords: Humans; Hospital Units; Hospitalization; Length of Stay; Outcome Assessment, Health Care; Patient Care Team; Prognosis; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stroke; Stroke/mortality; Stroke/therapy; Stroke Rehabilitation; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care

Review question Does organised inpatient (stroke unit) care improve the recovery of people with stroke in hospital compared with conventional care in general wards?

Background Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care is a form of care provided in hospital by nurses, doctors, and therapists who specialise in looking after people with stroke. They aim to work as a co‐ordinated team to provide the most appropriate care tailored to the needs of individual people with stroke.

Study characteristics We identified 29 trials involving 5902 participants (search completed 2 April 2019). Participants who were recruited had had a recent stroke and required admission to hospital. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care was provided in a variety of ways including stroke ward (care provided in a discrete stroke ward), mixed rehabilitation ward (setting seeking to improve care for people with stroke within a mixed rehabilitation ward), and mobile stroke team (peripatetic team looking after people with stroke across a range of wards).

Key results At an average of 12 months after their stroke, people who received organised inpatient (stroke unit) care were more likely to be alive (an extra two people surviving for every 100 receiving stroke unit care; moderate‐quality evidence) and living at home (an extra six patients for every 100 receiving stroke unit care; moderate‐quality evidence). They also were more likely to be independent in daily activities (an extra six patients for every 100 receiving stroke unit care; moderate‐quality evidence). The apparent benefits were seen in men and women, older and younger patients, and people with different types of stroke and different stroke severity. Benefits were most obvious when the stroke unit was based in a discrete stroke ward.

Quality of the evidence We downgraded the quality of evidence to 'moderate' for the main outcomes because it was impossible to hide the treating service from participants or healthcare workers. These conclusions were not dependent on trials judged to be of lower quality because of poor design or missing data. More information was missing for some of the other outcome measures and analyses, which we have downgraded to low‐quality evidence.

Conclusion People with stroke who receive organised inpatient (stroke unit) care are more likely to be alive, living at home, and independent in looking after themselves one year after their stroke. Apparent benefits were seen across a broad range of people with stroke. Various types of stroke units have been developed. The best results appear to come from stroke units based in a dedicated stroke ward.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care versus alternative service.

| Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care compared with alternative service | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute stroke Settings: hospital Intervention: organised inpatient (stroke unit) care Comparison: alternative service (contemporary conventional care) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Alternative service | Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care | |||||

|

Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6 or requiring institutional care; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 1.1) |

577 per 1000 | 517 per 1000 (497 to 547) |

OR 0.77 (0.69 to 0.87) | 5336 (26) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 1.2) |

219 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (179 to 209) |

OR 0.76 (0.66 to 0.88) |

5902 (29) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 1.3) |

405 per 1000 | 345 per 1000 (315 to 375) |

OR 0.76 (0.67 to 0.85) |

4887 (25) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 1.4) |

609 per 1000 | 549 per 1000 (519 to 567) |

OR 0.75 (0.66 to 0.85) | 4854 (24) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Subjective health status score Participant quality of life (Nottingham Health Profile; Quality of Life Scale) |

There was a pattern of improved results among stroke unit survivors, with results attaining statistical significance in 2 individual trials | N/A | 843 (3) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

Data from 3 trials only High rate of missing data |

|

| Patient satisfaction or preference | We could find no systematically gathered information on patient preferences | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

| Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution (Analysis 1.5) | Mean length of stay across the control groups ranged from 12.1 to 123 days | Mean length of stay for the intervention groups was, on average, 4.3 days less (7.9 days less to 0.7 days more) | SMD 0.16 lower (0.33 lower to 0.01 higher) |

4162 (19) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Different definitions and imprecise measures of length of stay were reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable; OR: odds ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded for potential risk of performance bias.

bDowngraded for unexplained heterogeneity.

cDowngraded for imprecision

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 1: Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 2: Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 3: Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 4: Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 5: Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution or both

Summary of findings 2. Stroke ward versus general medical ward.

| Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care compared with general medical ward care for stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute stroke Settings: hospital Intervention: stroke ward care Comparison: general medical ward care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| General medical ward care | Stroke ward care | |||||

|

Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6 or requiring institutional care; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 2.1) |

549 per 1000 | 499 per 1000 (459 to 529) |

OR 0.78 (0.68 to 0.91) | 3321 (14) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 2.2) |

242 per 1000 | 202 per 1000 (172 to 222) |

OR 0.75 (0.63 to 0.90) |

3523 (15) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 2.3) |

383 per 1000 | 323 per 1000 (283 to 353) |

OR 0.74 (0.63 to 0.87) |

2924 (13) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 2.4) |

602 per 1000 | 532 per 1000 (502 to 572) |

OR 0.75 (0.64 to 0.88) | 2839 (12) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Sensitivity analysis based on trial quality suggested no alteration of conclusions |

|

Subjective health status score Participant quality of life (Nottingham Health Profile; Quality of Life Scale) |

There was a pattern of improved results among stroke unit survivors, with results attaining statistical significance in 2 individual trials | N/A | 535 (2) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

Data from 3 trials only High rate of missing data |

|

| Patient satisfaction or preference | We could find no systematically gathered information on patient preferences | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

| Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution (Analysis 2.5) | Mean length of stay across control groups ranged from 12.8 to 123 days | Mean length of stay for the intervention groups was, on average, 2.2 days less (5.2 days less to 0.8 days more) | SMD 0.13 lower (0.29 lower to 0.04 higher) |

2547 (10) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Different definitions and imprecise measures of length of stay were reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable; OR: odds ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded for potential risk of performance bias.

bDowngraded for unexplained heterogeneity.

cDowngraded for imprecision

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Stroke ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 1: Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Stroke ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 2: Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Stroke ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 3: Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Stroke ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 4: Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Stroke ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 5: Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution

Summary of findings 3. Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward.

| Mobile stroke team care compared with general medical ward care for stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute stroke Settings: hospital Intervention: mobile stroke team care Comparison: general medical ward care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| General medical ward care | Mobile stroke team care | |||||

|

Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6 or requiring institutional care; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 3.1) |

712 per 1000 | 672 per 1000 (582 to 752) |

OR 0.80 (0.52 to 1.22) |

438 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | As dependency data were complete, these are the same data as for death or dependency |

|

Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 3.2) |

259 per 1000 | 279 per 1000 (189 to 359) |

OR 1.08 (0.71 to 1.65) |

438 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

|

Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 3.3) |

481 per 1000 | 531 per 1000 (451 to 611) |

OR 1.27 (0.84 to 1.93) |

438 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

|

Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 3.4) |

712 per 1000 | 672 per 1000 (582 to 752) |

OR 0.80 (0.52 to 1.22) |

438 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | As dependency data were complete, these are the same data as for poor outcome |

|

Subjective health status score Participant quality of life (EuroQol) |

No apparent differences between groups | N/A | 308 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

Data from 1 trial only | |

| Patient satisfaction or preference | We could find no systematically gathered information on patient preferences | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

|

Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution (Analysis 3.5) |

No data available | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded for potential risk of performance bias.

bDowngraded for imprecision.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward, Outcome 1: Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward, Outcome 2: Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward, Outcome 3: Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward, Outcome 4: Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward, Outcome 5: Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution

Summary of findings 4. Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward.

| Mixed rehabilitation ward care compared with general medical ward care for stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with acute stroke Settings: hospital Intervention: mixed rehabilitation ward care Comparison: general medical ward care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| General medical ward care | Mixed rehabilitation wardcare | |||||

|

Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6 or requiring institutional care; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 4.1) |

574 per 1000 | 474 per 1000 (404 to 554) |

OR 0.65 (0.47 to 0.90) |

630 (6) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | As dependency data were complete, these are the same data as for death or dependency |

|

Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 4.2) |

171 per 1000 | 161 per 1000 (101 to 211) |

OR 0.91 (0.58 to 1.42) |

630 (6) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

|

Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up (median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 4.3) |

451 per 1000 | 371 per 1000 (291 to 451) |

OR 0.71 (0.51 to 0.99) |

578 (5) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

|

Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up (modified Rankin score 3 to 6; median 12‐month follow‐up) (Analysis 4.4) |

574 per 1000 | 474 per 1000 (404 to 554) |

OR 0.65 (0.47 to 0.90) |

630 (6) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low a,b | As dependency data were complete, these are the same data as for poor outcome |

| Subjective health Status score | No data available | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

| Patient satisfaction or preference | We could find no systematically gathered information on patient preferences | N/A | N/A | N/A | No data available | |

| Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution (Analysis 4.5) | Mean length of stay across control groups ranged from 30.5 to 129.5 days | Mean length of stay for the intervention groups was, on average, 3.9 days more (13.5 days less to 21.5 days more) | MD 0.08 more (0.21 lower to 0.37 higher) |

387 (3) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | Different definitions and imprecise measures of length of stay were reported |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; N/A: not applicable; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded for potential risk of performance bias.

bDowngraded for imprecision.

cDowngraded for unexplained heterogeneity.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 1: Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 2: Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 3: Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 4: Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward, Outcome 5: Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is now the third leading cause of disability (Murray 2012), and it is the second leading cause of mortality worldwide (Lozano 2012). The global disease burden of stroke increased by 19% between 1990 and 2010 (Murray 2012), and current projections estimate the number of deaths worldwide will rise to 6.5 million in 2015 and to 7.8 million in 2030 (Strong 2007). Interventions that are applicable to a majority of people with stroke and that aim to reduce associated mortality and disability are essential.

During their initial illness, people with stroke are frequently admitted to hospital, where they can receive care in a variety of ways and in a range of settings. Traditionally, care for people with stroke was provided within departments of general (internal) medicine, neurology, or medicine for the elderly, where they would be managed alongside a range of other patient groups. A more focused approach to the treatment of people with stroke in hospital has been developed.

Description of the intervention

Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care is the term used to describe focused care for people with stroke in hospital under a multi‐disciplinary team of individuals who specialise in stroke management (SUTC 1997a). This concept is not new, and its value has been debated for more than 30 years (Ebrahim 1990; Garraway 1985; Langhorne 1993; Langhorne 1998; Langhorne 2012). In essence, the debate has concerned whether the perceived effort and cost of focusing the care of people hospitalised with stroke within specially organised units would be matched by tangible benefits for the people receiving that care. In particular, would more people survive and make a good recovery as a result of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care?

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review of all available trials previously described the range of characteristics of stroke unit care and addressed the question of whether improving the organisation of inpatient stroke care can bring about improvements in important patient outcomes (SUTC 1997a). This review continues to be extended and updated within the Cochrane Library (SUTC 2001; SUTC 2007; SUTC 2013). Since the last update, network meta‐analysis (NMA) has become established as an approach for handling multiple comparisons. We have added NMA to our updated review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care compared with an alternative service (usually contemporary conventional care)

To use a network meta‐analysis (NMA) approach to assess different types of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for people admitted to hospital after a stroke (the standard comparator was care in a general ward)

Originally, this systematic review was conducted to address four broad questions.

What are the characteristic features of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care?

Can organised inpatient (stroke unit) care provide better patient outcomes than alternative forms of care?

Are any benefits apparent across a range of patient groups?

Are any benefits apparent across different approaches to delivering organised stroke unit care? In particular, we hypothesised that organised care would be more effective than care provided in general medical wards, but that different forms of organised care would achieve similar outcomes.

Within the current version of this review, we wished to establish whether previous conclusions were altered by the inclusion of new outcome data from recent trials and further analysis via NMA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled clinical trials that compared an organised system of inpatient (stroke unit) care with an alternative form of inpatient care. This was usually contemporary conventional care but could include an alternative model of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care (see Types of interventions). Previous versions of this review included trials with quasi‐random treatment allocation (such as bed availability or date of admission) (SUTC 1997a; SUTC 2001; SUTC 2007). However, in an effort to ensure that this ongoing systematic review focuses on data from trials with strict randomisation procedures, we excluded all quasi‐randomised trials in the previous update (SUTC 2013). We would have included cluster‐randomised trials, but we identified none. We excluded cross‐over trials because of cross‐over of effects.

Types of participants

Any person admitted to hospital who had suffered a stroke was eligible. We recorded the delay between stroke onset and hospital admission but did not use this as an exclusion criterion. We used a clinical definition of stroke: focal neurological deficit due to cerebrovascular disease, excluding subarachnoid haemorrhage and subdural haematoma.

Types of interventions

Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care can be considered a complex organisational intervention comprising multi‐disciplinary staff providing a complex package of care to people with stroke in hospital. In the original version of this review, the first question was whether organised inpatient (stroke unit) care could improve outcomes compared with contemporary conventional care (usually in general wards) (SUTC 1997a). We then had to modify the analyses in a minor way to reflect the emerging pattern of service organisation and to allow the comparison of 'more organised' versus 'less organised' services (for which the latter was usually contemporary conventional care). We did this because some recent trials have addressed new questions and included comparisons of two services, both of which met the basic definition of organised (stroke unit) care. In the original service descriptions used in this review (SUTC 1997a), service organisation was considered as a hierarchy comprising the following.

-

Stroke ward: where a multi‐disciplinary team including specialist nursing staff based in a discrete ward cares exclusively for people with stroke. This category included the following subdivisions.

-

Acute stroke units that accept patients acutely but discharge early (usually within seven days); these appear to fall into three broad subcategories.

'Intensive' model of care with continuous monitoring, high nurse staffing levels, and the potential for life support.

'Semi‐intensive' model of care with continuous monitoring, high nurse staffing, but no life support facilities.

'Non‐intensive' model of care with none of the above.

Rehabilitation stroke units that accept patients after a delay, usually of seven days or longer, and focus on rehabilitation.

Comprehensive (i.e. combined acute and rehabilitation) stroke units that accept patients acutely but also provide rehabilitation for at least several weeks if necessary. Both the rehabilitation unit model and the comprehensive unit model offer prolonged periods of rehabilitation.

-

Mixed rehabilitation ward: where a multi‐disciplinary team including specialist nursing staff in a ward provides a generic rehabilitation service but not exclusively caring for people with stroke.

Mobile stroke team: where a peripatetic multi‐disciplinary team (usually excluding specialist nursing staff) provides care in a variety of settings.

General medical ward: where care is provided in an acute medical or neurology ward without routine multi‐disciplinary input.

For the NMA eligibility assessment, we considered the transitivity (similarity) of trials included in the network (see Data synthesis), which requires all interventions to be legitimate alternatives. All of the four main categories have been used to provide care for unselected acute stroke patients and can be considered broadly comparable for the purpose of an NMA. The general medical ward group was the reference group,

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

In the previous version of this review, the primary analyses examined death, dependency, and the requirement for institutional care at the end of scheduled follow‐up of the original trial (SUTC 2013). We categorised dependency into two groups, where we took 'independent' to mean that an individual did not require physical assistance for transfers, mobility, dressing, feeding, or toileting. We considered individuals who failed any of these criteria 'dependent'. The criteria for independence were approximately equivalent to a modified Rankin score of 0 to 2 or a Barthel Index greater than 18 out of 20 (Wade 1992). We took the requirement for long‐term institutional care to mean care in a residential home, a nursing home, or a hospital at the end of scheduled follow‐up.

In view of changes in reporting standards, for this update we have now provided a single composite primary outcome: poor outcome: death or dependency or requiring institutional care (if dependency data were not available). This allowed us to keep the primary focus of the review (i.e. the focus on independent survival as an outcome), while optimising the quantity of data available.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures now include:

death;

death or institutional care;

death or dependency;

patient subjective health status (measured using tools such as the Nottingham Health Profile, EuroQol, Short Form‐36);

patient and carer satisfaction (recorded on a Likert scale or as responses to statements); and

duration of stay in hospital or institution or both.

Outcomes are reported at the end of scheduled follow‐up. Some trials subsequently provided supplementary extended follow‐up data, which are presented separately.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the methods for the Cochrane Stroke Group Specialised register. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged the translation of relevant papers published in languages other than English.

Electronic searches

We searched the trials registers of the Cochrane Stroke Group (2 April 2019). In addition, in collaboration with the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019; Issue 4), in the Cochrane Library (searched 2 April 2019) (Appendix 1); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 1 April 2019) (Appendix 2); Embase Ovid (1974 to 1 April 2019) (Appendix 3); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) EBSCO (1982 to 2 April 2019) (Appendix 4).

We searched the following registers of ongoing trials using the keyword 'stroke'.

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 2 April 2019).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 2 April 2019).

CenterWatch Clinical Trials Listing Service (www.centerwatch.com; searched 13 August 2018).

Community Research & Development Information Service (of the European Union) (cordis.europa.eu/en/home.html; searched 13 August 2018).

South African National Clinical Trial Register (www.sanctr.gov.za; searched 13 August 2018).

The Internet Stroke Center ‐ Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials;searched 13 August 2018).

Clinical Trials Results register (www.clinicaltrialresults.org; searched 2 April 2019).

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing trials, we:

performed citation tracking using Web of Science Cited Reference Search for all included studies;

searched the reference lists of included trials and all relevant articles;

obtained further information from individual trialists; and

contacted other researchers in the field and publicised our preliminary findings at stroke conferences in UK, Scandinavia, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, USA, India, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Italy, and Hong Kong.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this updated review, one review author (PL) read the titles and abstracts of records obtained through the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained full copies of the remaining studies, and two review authors (PL and SR) independently selected studies for inclusion based on the following eligibility criteria.

Randomised controlled trial.

Service intervention providing a form of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care.

Service aim to improve functional recovery and survival after stroke.

Trial of stroke patients.

We tried to establish the characteristics of unpublished trials through discussion with the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist before analysing the results.

Data extraction and management

If possible, the principal review author (PL) obtained descriptive information about the service characteristics of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care and conventional care settings through a structured interview or correspondence conducted with the trial co‐ordinators (n = 19). We obtained additional information from published sources. We then allocated trials to service subgroups. We confirmed outcome data from published sources and supplemented them with unpublished information provided by the co‐ordinator of each individual trial. We asked trialists to provide information on the number of participants who were dead or dependent and the number requiring institutional care or missing at the end of scheduled follow‐up. For this updated review, two review authors (PL, SR) independently extracted information using a standard data extraction form.

We sought subgroup information on potential effect modifiers primarily for the combined outcome of death or requiring institutional care. We obtained unpublished aggregated data for a majority of trials, but insufficient quantities of individual patient data were available to allow a comprehensive individual patient data analysis.

We obtained subgroup data regarding the following participant groups (see SUTC 1997a for details).

Age: up to 75 years or 75 years or older.

Sex: men or women.

-

Stroke severity: dependency at the time of randomisation (usually within one week of the index stroke).

Mild stroke: equivalent to a Barthel Index of 10 to 20 out of 20 during the first week.

Moderate stroke: equivalent to a Barthel Index of 3 to 9 out of 20 during the first week.

Severe stroke: equivalent to a Barthel Index of 0 to 2 out of 20 during the first week.

Stroke type: ischaemic or haemorrhagic based on neuroimaging.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool, as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Two review authors identified the method of random sequence generation, the method of concealment of treatment allocation, blinding of participants and personnel, the presence of blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of follow‐up, and evidence of selective reporting. We used these potentially important factors in sensitivity analyses, but we did not use them as exclusion criteria. The principal review author then used this information to inform the categorisations within the 'Summary of findings' tables and the GRADE allocations.

Measures of treatment effect

When our analyses of poor outcome, death, dependency, or institutionalisation at the end of scheduled follow‐up were reported, we analysed these using the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for an adverse outcome.

We aimed to record length of stay in hospital or in an institution as the mean and standard deviation (SD). When only medians were available, we assumed these were approximate to the mean. When no other data were provided with the mean value, we inferred the SD as being at least as large as those in comparable trials using the same measure. Because length of stay was reported in a variety of ways, we checked the results obtained with the mean difference (MD) using the standardised mean difference (SMD) and the 95% CI.

We anticipated that measures of subjective health status would be analysed as mean differences, and measures of satisfaction would be analysed as odds ratios for particular responses.

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipated that most trials would have a simple parallel‐group design in which each individual was randomised to one of two treatment groups. When a trial had three (or more) treatment groups, we planned to analyse each treatment arm as a separate study. We have not included cross‐over trials because of the likelihood or carryover effects.

Dealing with missing data

When data were missing for the outcome of death, dependency, or institutionalisation, we assumed the participant to be alive, independent, and living at home. We aimed to explore the implications of these assumptions in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to determine heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plot and by using the I² statistic. We defined significant heterogeneity as I² greater than 50%. When significant heterogeneity occurred, we explored potential sources using pre‐planned sensitivity analyses. Assessments of transitivity and consistency are discussed in the NMA section under Data synthesis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We employed a comprehensive search strategy in an effort to avoid reporting biases. To identify unpublished studies, we searched trial registers and contacted trialists and other experts in the field. We planned to inspect funnel plots if enough studies were available.

Data synthesis

Pairwise comparisons

When we did not have access to individual patient data, two review authors (PL, SR) extracted data from published reports. When individual patient data were available, we checked them for internal consistency and consistency with published reports. One review author entered data into the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014), and a second review author checked the entries. We analysed binary outcome data using OR and 95% CI. We analysed continuous outcome data using SMD and 95% CI. By default, we used a fixed‐effect model first, but we corroborated results by using a random‐effects model if heterogeneity was significant.

When data were available, we carried out subgroup analyses for age, sex, stroke severity, and stroke type. Through subgroup analyses, we considered the degree of interaction between subgroups (Higgins 2011).

Network meta‐analysis

In this version of the review, we include a newer approach to meta‐analysis in the form of a network meta‐analysis (NMA) of trial data. The original aim of this review was to compare the effects of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care versus conventional care. We expected that within this broad definition, the included trials would comprise a range of treatment comparisons (which could include stroke wards, mobile stroke teams, mixed rehabilitation wards) with conventional care in general wards. In addition, later trials have addressed newer questions comparing different forms of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care (e.g. stroke ward versus mobile stroke team).

We have retained the previous analysis, which was organised in a hierarchical manner (organised stroke care versus alternative service; organised stroke care versus general ward; different systems of organised care). However, we now include an NMA to explore, when possible, the impact of different systems of stroke care. We used MetaInsight software, which uses a frequentist approach and is designed specifically for this role ‐ to enable us to conduct our NMA (Owen 2019).

An NMA uses information from both direct and indirect estimates of treatment effect (Tonin 2017). Direct estimates are provided by a head‐to‐head comparison (e.g. treatment A versus treatment B). Indirect estimates are provided by two or more head‐to‐head comparisons that share a common comparator (e.g. when A versus B is the comparison of interest, then trials with A versus C and with B versus C are used). A trial network is then formed, using trials that allow, through direct and indirect comparisons, calculation of the relative effects of all treatments versus each other (or versus a single comparator). The results of such analyses are usually presented as comparisons against a common comparator group (e.g. general ward). It is also possible to present a rank analysis, which ranks treatment groups on the likelihood of being most/least effective.

A key assumption in NMA is that of transitivity (or similarity). This concerns the validity of making indirect comparisons and assumes that treatment effects are 'exchangeable' across the included trials, and that all treatments are 'jointly randomisable'. In other words, all treatment categories could feasibly be randomised in the same trial, and those that are not treatment arms in any given trial are 'missing at random' (Lu 2006). As this assumption cannot be formally tested statistically, it was judged through consideration of trial settings and characteristics, patient characteristics, and treatment mechanisms, and to investigate if any differences would be expected to modify relative treatment effects. Two review authors independently extracted the relevant information, and the principal review author made the final judgement.

A second important assumption (known as the consistency assumption) assumes that it is feasible to make indirect comparisons between two treatments, and that the indirect evidence is consistent with the direct evidence (Lu 2006). The consistency assumption can be evaluated statistically by comparing the difference between the direct estimate and the indirect estimate for each loop of evidence. Therefore, we examined for any important differences in numerical results between direct, indirect, and network results.

GRADE and 'Summary of findings'

We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables and used GRADE criteria to assess the quality of evidence. 'Summary of findings' tables included the new primary outcome (poor outcome) and the three main clinical outcomes included in previous reviews (death, death or requiring institutional care, death or dependency) plus subjective health status, patient satisfaction, and length of stay in a hospital or institution. All were recorded at the end of scheduled follow‐up.

This update included an NMA whereby different types of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care were compared with care provided in a general ward (see below). For the NMA, we used the approach of the GRADE group as outlined below (Brignardello 2018; Puhan 2014).

Present direct and indirect treatment estimates for each comparison of the evidence network.

Rate the quality of each direct and indirect effect estimate (downgrading for risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias).

Present the NMA estimate for each comparison of the evidence network.

Rate the quality of each NMA effect estimate (as above).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses involved a re‐analysis stratified by participant or service subgroup using tabular subgroup data provided by trialists or obtained from published sources. We used a fixed‐effect approach unless heterogeneity was statistically significant, and all subgroup analyses considered the degree of interaction between subgroups (Higgins 2011). We applied subgroup analyses only to the main (first) comparison to minimise the risk of false‐positive results.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses around key aspects of risk of bias that we identified during our assessment of risk of bias (i.e. concealment of treatment allocation, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of follow‐up, and a fixed period of follow‐up). We applied sensitivity analyses only to the main (first) comparison.

Results

Description of studies

This is the fifth update of this Cochrane Review. The key references are described in the following relevant tables: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy for previous versions of this review yielded 28 eligible trials (Included studies), seven awaiting classification (Studies awaiting classification), three ongoing studies (Ongoing studies), and 28 excluded studies (Excluded studies).

For this updated review, searches of Embase, CINHAL, MEDLINE, and CENTRAL revealed 16,562 records. Searches of Cochrane trials registers and other ongoing trials registers identified 432 new potentially eligible trials for consideration based on the four selection criteria (Figure 1). After exclusion of duplicate records and those that were obviously irrelevant, we were left with 32 abstracts for screening. Of these, one was a new record of a previously identified study (Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994), one was not randomised, and 19 described interventions that did not match organised inpatient (stroke unit) care.

1.

Flow diagram illustrating the results of updated searches.

Of the remaining 13 articles retrieved, we excluded 10: seven were not randomised (Akhtar 2015; Al‐Qahtany 2014; Fu 2006; He 2014; Inoue 2013; Rai 2016; Raiborirug 2017), and three did not meet the definition of stroke unit (Felix 2016; Janssen 2014; Middleton 2018). Two are ongoing studies (China (Wang) 2015; Russia 2017), and we included one new trial (New South Wales 2014).

Therefore, this updated review incorporates 29 randomised controlled trials with 5902 participants.

Included studies

Service characteristics within organised (stroke unit) care and conventional care settings

Descriptive information was available for all trials: for eight trials, we had access to published information (Birmingham 1972; Guangdong 2008; Guangdong 2009; Huaihua 2004; Hunan 2007; Illinois 1966; New South Wales 2014; New York 1962); for two trials, we had detailed unpublished information (Beijing 2004; Joinville 2003); and for the remaining 19 trials, we carried out a structured interview with the trial co‐ordinator to determine the service characteristics.

Our original publication outlined the features of stroke unit trials (SUTC 1997a). In summary, organised inpatient (stroke unit) care was characterised by:

co‐ordinated multi‐disciplinary rehabilitation;

staff with a specialist interest in stroke or rehabilitation, or both;

routine involvement of carers in the rehabilitation process; and

regular programmes of education and training.

Several factors indicating more intensive or more comprehensive input of care were also associated with the stroke unit setting. Various service models of care exist (Table 5), but core characteristics that were invariably included in the stroke unit setting were (1) multi‐disciplinary staffing, that is, medical, nursing, and therapy staff (usually including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, social work); and (2) co‐ordinated multi‐disciplinary team care incorporating meetings at least once per week (SUTC 1997a). When both of the compared services could satisfy the description of stroke unit care, the local conventional system of care was taken as the control service.

1. Typical characteristics of different models of organised stroke care.

| Name | Structure | Patients | Service type | Admission | Discharge | Features |

| Stroke ward | Ward | Stroke | Various (see below) | Various (see below) | Various (see below) | Various (see below) |

| Acute stroke ward | Ward | Stroke | Acute | Acute (hours) | Days | Close physiological monitoring, often followed by care in separate rehabilitation ward if required |

| Comprehensive stroke warda | Ward | Stroke | Acute, rehabilitation | Acute (hours) | Days to weeks | Acute care and rehabilitation; conventional staffing levels |

| Rehabilitation stroke ward | Ward | Stroke | Rehabilitation | Delayed (days) | Weeks | Focus on rehabilitation |

| Mobile stroke team | Mobile team | Stroke | Mobile stroke team | Variable | Days to weeks | Peripatetic care to patients in general wards; medical and rehabilitation advice |

| Mixed rehabilitation ward | Ward | Mixed | Rehabilitation | Variable | Weeks | Mixed patient group; focus on rehabilitation |

| Intensive care | Ward | Mixed | Acute, intensive | Acute (hours) | Days | High nurse staffing; life support facilities |

aTwo trials tested a comprehensive stroke ward incorporating traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) such as acupuncture.

Service comparisons within the 29 trials with outcome data are detailed in Table 6. The total number of comparisons is greater than the number of trials because in three trials, participants could be randomised to one of two alternatives to stroke unit care; two of these trials used a stratified randomisation procedure (Nottingham 1996; Orpington 1993), and one did not (Dover 1984). In two small trials, the conventional care (general medical) group also received input from a specialist nurse (Illinois 1966; New York 1962). Although this was not strictly general medical ward care, we have included this information because relatively little novel nursing input appears to be available. Exclusion of these trials would not substantially alter the conclusions of the systematic review. For one trial, some participants appear to have been treated outside the rehabilitation wards (i.e. by peripatetic team care), but the number is unclear (New York 1962). This trial is currently classified as a mixed rehabilitation ward.

2. Service comparisons in standard analyses.

| Trials | Participants | Index (stroke unit) care | Conventional care | Reference |

| 15 | 3521 | Stroke ward | General medical ward | Athens 1995, Beijing 2004, Dover 1984 (GMW), Edinburgh 1980, Goteborg‐Ostra 1988, Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994, Guangdong 2009, Huaihua 2004, Joinville 2003, Nottingham 1996 (GMW), Orpington 1993 (GMW), Orpington 1995, Perth 1997, Svendborg 1995, Trondheim 1991 |

| 6 | 630 | Mixed rehabilitation ward | General medical ward | Birmingham 1972, Helsinki 1995, Illinois 1966, Kuopio 1985, New York 1962; Newcastle 1993 |

| 2 | 438 | Mobile stroke team (peripatetic care) | General medical ward | Manchester 2003, Montreal 1985 |

| 4 | 542 | Stroke ward | Mixed rehabilitation ward | Dover 1984 (MRW), Nottingham 1996 (MRW), Orpington 1993 (MRW), Tampere 1993 |

| 1 | 304 | Stroke ward (comprehensive) | Mobile stroke team | Orpington 2000 |

| 1 | 54 | Stroke ward (acute) | Stroke ward (comprehensive unit) | Groningen 2003 |

| 1 | 47 | Stroke ward (comprehensive) | Stroke wards (acute+rehabilitation) | New South Wales 2014 |

| 2 | 366 | Stroke ward (plus TCM) | Stroke ward (without TCM) | Guangdong 2008, Hunan 2007 |

TCM: traditional Chinese medicine.

Four trials compared a model of stroke unit care using integrated traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (e.g. acupuncture, herbal remedies) versus standard 'Western medicine' stroke unit care (Guangdong 2008; Hunan 2007), or a general medical ward (Guangdong 2009). One trial compared a comprehensive stroke ward within a neurology unit with a general medical ward (Huaihua 2004). The duration of rehabilitation provided in all four trials was unclear, and only two trials reported the timing of randomisation (Guangdong 2009; Huaihua 2004).

Of the 29 included trials, 23 incorporated rehabilitation lasting several weeks if required: 17 of these units admitted participants acutely, and eight after a delay of one or two weeks. Two trials compared an acute stroke unit with early transfer to conventional rehabilitation if required (Groningen 2003; New South Wales 2014). One trial proved difficult to categorise as it contained elements of an acute unit but offered some rehabilitation (Athens 1995). It is classified here as a comprehensive stroke unit trial. The duration of rehabilitation was unclear for two Chinese trials (Guangdong 2008; Hunan 2007). No trials evaluated an 'intensive care' model of a stroke unit.

The classification of trials is outlined in Table 5, and the numbers in each comparison are shown in Table 6.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Of the 38 excluded studies, 21 were not strictly randomised, six were evaluations of care pathways, four had no available outcome data, four evaluated an intervention that did not fit our description of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care, two treated intervention and control participants within the same unit, and one reported retrospective data from a previous study.

Risk of bias in included studies

See the 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2), the 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 3), and the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Sixteen trials used a secure and clearly concealed randomisation procedure (both random sequence generation and allocation concealment), and we judged these to be at low risk of bias (Athens 1995; Dover 1984; Edinburgh 1980; Goteborg‐Ostra 1988; Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Helsinki 1995; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Orpington 1993; Orpington 2000; Svendborg 1995; Tampere 1993; Trondheim 1991). The remaining trials were at unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

It is very challenging to blind participants or treating staff to treatment allocation, and only one trial reported any attempts to do so (New South Wales 2014). The remaining trials had unclear risk of bias. However, it is worth noting that most studies completed long‐term follow‐up at a time when participants and families often could not recall any details of their acute treatment.

Twelve trials used an unequivocally blinded final assessment for all participants (Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Helsinki 1995; Hunan 2007; Joinville 2003; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 2000; Perth 1997). Eight trials had unclear risk of bias (Beijing 2004; Goteborg‐Ostra 1988; Guangdong 2008; Guangdong 2009; Huaihua 2004; Orpington 1995; Svendborg 1995; Trondheim 1991), and we judged eight trials to be at high risk of bias (Athens 1995; Birmingham 1972; Dover 1984; Edinburgh 1980; Illinois 1966; Newcastle 1993; Orpington 1993; Tampere 1993).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 19 trials to be at low risk of bias (Athens 1995; Beijing 2004; Dover 1984; Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Guangdong 2009; Helsinki 1995; Illinois 1966; Joinville 2003; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Newcastle 1993; Orpington 1995; Perth 1997; Svendborg 1995; Tampere 1993; Trondheim 1991). The remaining nine trials were at unclear risk (Birmingham 1972; Edinburgh 1980; Goteborg‐Ostra 1988; Guangdong 2008; Huaihua 2004; Hunan 2007; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 1993; Orpington 2000).

Ten trials had minor omissions of death and place of residence data (26 stroke unit participants and 35 controls in total) (Birmingham 1972; Dover 1984; Edinburgh 1980; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 1993; Orpington 2000; Tampere 1993). For the purpose of our analysis, we assumed these participants were alive and living at home, which may have introduced a minor bias in favour of the control group.

Selective reporting

We judged selective reporting bias to be low risk in 15 trials, largely because we obtained unpublished data from the trialists (Athens 1995;Beijing 2004;Birmingham 1972;Edinburgh 1980;Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994;Groningen 2003;Joinville 2003;Manchester 2003;Nottingham 1996;Orpington 1993;Orpington 1995;Orpington 2000;Perth 1997;Tampere 1993;Trondheim 1991). We classified the remaining 13 trials as having unclear risk of reporting bias (Dover 1984; Goteborg‐Ostra 1988; Guangdong 2008; Guangdong 2009; Helsinki 1995; Huaihua 2004; Hunan 2007; Illinois 1966; Kuopio 1985; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Newcastle 1993; Svendborg 1995).

Other potential sources of bias

Most of the Stroke Unit Trialists Collaboration members carried out trials that are included in the review. However, trialists were not involved in selection or assessment of their own trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Results of the systematic review are presented in five sections as pairwise comparisons followed by NMA.

Pairwise comparisons

These comparisons are listed in five sections as follows.

-

Section 1. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care versus alternative care (Comparison 1).

First, we have outlined the main outcomes for the comparison of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care with an alternative service. Therefore, this section examines the impact of all types of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care on patient outcomes. For trials where both services compared could satisfy the definition of stroke unit care (Table 5), we have presented the system of care that we considered to be conventional care in the trial as the control service.

This section includes analyses of different subgroups of participants and sensitivity analyses by trial quality.

We have then described the results for the most common comparisons of different forms of organised stroke unit care versus a general medical ward: stroke ward, mobile stroke team, and mixed rehabilitation ward.

Section 2. Stroke ward versus general medical ward (Comparison 2).

Section 3. Mobile stroke team versus general medical ward (Comparison 3).

Section 4. Mixed rehabilitation ward versus general medical ward (Comparison 4).

Finally, we have presented the results for any direct comparisons of organised care in a stroke ward versus a different form of organised stroke unit care.

Section 5. Different systems of organised care: stroke ward versus alternative organised care (Comparison 5).

Section 1. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care versus alternative service (Comparison 1)

Outcome 1.1. Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Outcome data were available for 26 trials (5336 participants) (Analysis 1.1). The summary result indicated a significant reduction in the odds of a poor outcome (odds ratio (OR) 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69 to 0.87; moderate‐quality evidence) recorded at the end of scheduled follow‐up (median follow‐up 12 months; range 6 weeks to 12 months) with no significant heterogeneity.The main methodological difficulties when dependency was used as an outcome were the degree of blinding at final assessment and the potential for bias if the assessor was aware of the treatment allocation. The results were unchanged when restricted to those trials in which an unequivocally blinded final assessment for all participants was undertaken (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.91) (Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Helsinki 1995; Joinville 2003; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 2000).

Outcome 1.2. Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Outcome data were available for all 29 trials (5902 participants) in which an organised inpatient (stroke unit) intervention was compared with an alternative service (Analysis 1.2). Case fatality recorded at the end of scheduled follow‐up (median follow‐up 12 months; range 6 weeks to 12 months) was lower in the organised (stroke unit) care group in 22 of 29 trials. The overall summary estimate included an OR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.88; moderate‐quality evidence). A borderline significant subgroup interaction was reported (P = 0.04), with more positive effects seen in subgroups based on trials of stroke wards.

Outcome 1.3. Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Outcome data were available for 24 trials (4887 participants) (Analysis 1.3). The median duration of follow‐up was 12 months (range 6 weeks to 12 months). The summary result indicated a significant reduction in the odds of a patient dying or requiring long‐term institutional care (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.85; moderate‐quality evidence). A subgroup interaction was noted (P = 0.01), with more positive effects usually seen in subgroups based on trials of stroke wards. When we excluded trials that had a very short or variable period of follow‐up, we found that the overall estimate of apparent benefit was unaffected (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.86) (Beijing 2004; Goteborg‐Ostra 1988; Groningen 2003; Illinois 1966; Montreal 1985; New York 1962; Orpington 1993; Orpington 1995).

Outcome 1.4. Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Outcome data were available for 24 trials (4854 participants) (Analysis 1.4). The summary result indicated a significant reduction in the odds of the combined adverse outcomes of death or dependency (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.85; moderate‐quality evidence) with no significant heterogeneity. The main methodological difficulties when dependency was used as an outcome were the degree of blinding at final assessment and the potential for bias if the assessor was aware of the treatment allocation. The results were unchanged (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.91) when restricted to those trials in which an unequivocally blinded final assessment for all participants was undertaken (Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Helsinki 1995; Joinville 2003; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; Montreal 1985; New South Wales 2014; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 2000).

Outcomes 1.5 and 1.6. Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution or both

Length of stay data were available for 19 individual trials (4162 participants) (Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6). Mean (or median) length of stay ranged from 11 to 162 days in stroke unit groups and from 12 to 129 days in control groups. Thirteen trials reported a shorter length of stay in the organised inpatient (stroke unit) group, and six a more prolonged stay. The calculation of a summary result for length of stay was subject to major methodological limitations: length of stay was calculated in different ways (e.g. acute hospital stay, total stay in hospital or institution), two trials recorded median rather than mean length of stay, and in two trials the SD had to be inferred from the P value or from the results of similar trials. Overall, use of a random‐effects model revealed no significant reduction in length of stay in the stroke unit group. The summary estimate was complicated by considerable heterogeneity that limits the extent to which more general conclusions can be inferred.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Organised stroke care versus alternative service, Outcome 6: Length of stay (days) in a hospital or hospital plus institution

We re‐analysed results according to whether length of stay was defined as stay in acute hospital only or total length of stay in a hospital or institution in the first year after stroke (Analysis 1.6). We found no significant difference between the two groups and no reduction in heterogeneity.

Participant satisfaction and subjective health status

Only three trials recorded outcome measures related to participant subjective health status (Nottingham Health Profile; EuroQol Quality of Life Scale) (Manchester 2003; Nottingham 1996; Trondheim 1991). In Nottingham 1996 and Trondheim 1991, there was a pattern of improved results among stroke unit survivors with results attaining statistical significance in the two trials. However, for Manchester 2003, there was no statistically significant difference between study groups. We could find no systematically gathered information on participant preferences.

Outcomes 1.7 to 1.10. Poor outcome, death, death or institutional care, and death or dependency at five‐year follow‐up

Three trials (1139 participants) carried out supplementary studies extending participant follow‐up to five years post stroke for the outcome of death (Athens 1995; Nottingham 1996; Trondheim 1991), and two trials (535 participants) carried out supplementary studies extending participant follow‐up to five years post stroke for the outcomes of death or institutionalisation and death or dependency (Nottingham 1996; Trondheim 1991). The OR for adverse outcomes continued to favour stroke unit care but with some heterogeneity: poor outcome 0.54 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.34), death 0.74 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.94), death or institutional care 0.59 (95% CI 0.33 to 1.05), and death or dependency 0.54 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.34).

Outcomes 1.11 to 1.14. Poor outcome, death, death or institutional care, and death or dependency at 10‐year follow‐up

Three trials (1139 participants) extended follow‐up to 10 years post stroke for the outcome of death (Athens 1995; Nottingham 1996; Trondheim 1991), and two trials (535 participants) extended follow‐up to 10 years post stroke for the outcomes of death or institutionalisation and death or dependency (Nottingham 1996; Trondheim 1991). Again, the summary results continued to favour stroke unit care but with increased heterogeneity and loss of statistical significance: poor outcome OR 0.70 (95% CI 0.27 to 1.80), death OR 0.66 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.03), death or institutional care OR 0.57 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.88), and death or dependency OR 0.70 (95% CI 0.27 to 1.80).

Sensitivity analyses by trial characteristics

Sensitivity analyses were applied only to the main (first) comparison to test confidence in the main hypothesis. In view of the variety of trial methods described, we carried out a sensitivity analysis based only on those trials with low risk of bias based on (1) secure concealment of allocation procedures, (2) unequivocally blinded outcome assessment, and (3) a fixed period of near complete follow‐up.

Secure concealment of allocation procedures: restricting analyses to the 16 trials with clearly reported random sequence generation and concealment of allocation did not substantially alter the odds of a poor outcome (0.79, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.91) (Figure 2).

Unequivocally blinded outcome assessment: restricting analyses to the 12 trials with clearly blinded outcome assessment did not substantially alter the odds of a poor outcome (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.89) (Figure 2).

A fixed period of near complete follow‐up: restricting analyses to the 15 trials that clearly reported a fixed period of follow‐up (with > 90% completeness of follow‐up) did not substantially alter the odds of a poor outcome (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91) (Included studies).

Eight trials met all of these quality criteria (Goteborg‐Sahlgren 1994; Groningen 2003; Helsinki 1995; Kuopio 1985; Manchester 2003; New South Wales 2014; Nottingham 1996; Orpington 2000). Within this group of trials, stroke unit care was associated with similar reductions in the odds of a poor outcome (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.91).

Subgroup analyses by patient characteristics

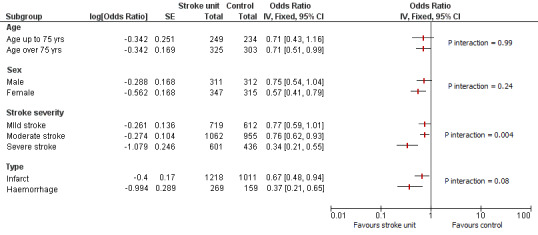

Pre‐defined subgroup analyses were based on previous versions of this review, and each subgroup analysis included data from at least nine trials (at least 1111 participants) (SUTC 1997a). These were based on participants' age, sex, and initial stroke severity. For this updated version of the review, we have incorporated additional data based on pathological stroke type (ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke). See Figure 4.

4.

Subgroup analysis by patient characteristics: poor outcome at the end of scheduled follow‐up. Analyses used the generic inverse variance approach. P values relate to the subgroup interaction.

Caution is needed when interpreting these subgroup analyses, particularly as a relatively small number of outcome events were observed, which limits statistical power. Therefore, subgroup analyses were applied only to the main (first) comparison. Furthermore, the results may change depending on the outcome chosen. These results indicate that in general, the magnitude of benefit seemed greater for participants with more severe stroke (the only significant subgroup interactions were for stroke severity: P = 0.004). However, stroke unit benefits are apparent across a range of participant subgroups (i.e. age, sex, initial stroke severity, and stroke type).

Section 2. Stroke ward versus general medical ward (Comparison 2)

Analyses comparing a stroke ward with a general medical ward comprised two subgroups of stroke ward: comprehensive and rehabilitation (see Table 5).

Outcome 2.1. Poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Fourteen trials (3321 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in a general ward (Analysis 2.1). Stroke ward care showed a reduction in the odds of a poor outcome by the end of scheduled follow‐up (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91; moderate‐quality evidence) with no subgroup interaction between the different types of stroke ward. Some minor heterogeneity (59%) was noted. Re‐analysis with a random‐effects model did not alter the conclusions.

Outcome 2.2. Death by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Fifteen trials (3523 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in a general ward (Analysis 2.2). Stroke ward care showed a reduction in the odds of death by the end of scheduled follow‐up (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.90; moderate‐quality evidence) with no subgroup interaction between the different types of stroke ward and no significant heterogeneity.

Outcome 2.3. Death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Thirteen trials (2924 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in a general ward (Analysis 2.3). Stroke ward care showed a reduction in the odds of death or institutional care by the end of scheduled follow‐up (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.87; moderate‐quality evidence) with no subgroup interaction between the different types of stroke ward and no significant heterogeneity.

Outcome 2.4. Death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up

Twelve trials (2839 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in a general ward (Analysis 2.4). Stroke ward care showed a reduction in the odds of death or dependency by the end of scheduled follow‐up (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88; moderate‐quality evidence) with no subgroup interaction between the different types of stroke ward. Some heterogeneity (63%) was noted. Re‐analysis with a random‐effects model did not alter the conclusions.

Outcome 2.5. Length of stay (days) in a hospital or institution

Ten trials (2547 participants) compared care in a stroke ward with care in a general ward (Analysis 2.4). Overall, stroke ward care showed no reduction in length of stay (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐2.19, 95% CI ‐5.19 to 0.82; low‐quality evidence). We found substantial heterogeneity (78%) and a significant subgroup interaction between the different types of stroke ward, which limits confidence in the results.

Participant satisfaction and subjective health status