Abstract

Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) co-occurs frequently with other mental health conditions, adding to the burden of disease and complexity of treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is efficacious for both OCD and two of its most common comorbid conditions, anxiety and depression. Therefore, treating OCD may yield secondary benefits for anxiety and depressive symptomatology. This study examined whether anxiety and/or depression symptoms declined over the course of OCD treatment and, if so, whether improvements were secondary to reductions in OCD severity, impairment, and/or global treatment response. The sample consisted of 137 youths who received 12 sessions of manualized CBT and were assessed by independent evaluators. Mixed models analysis indicated that youth-reported anxiety and depression symptoms decreased in a linear fashion over the course of CBT, however these changes were not linked to specific improvements in OCD severity or impairment but to global ratings of treatment response. Results indicate that for youth with OCD, CBT may offer benefit for secondary anxiety and depression symptoms distinct from changes in primary symptoms. Understanding the mechanisms underlying carryover in CBT techniques is important for furthering transdiagnostic and/or treatment-sequencing strategies to address co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms in pediatric OCD.

1. Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychiatric condition affecting up to 3% of the population (Zohar, 1999) and with typical onset during the pediatric period (Brakoulias et al., 2017; LaSalle, Cromer, Nelson, Kazuba, Justement, & Murphy, 2004). Pediatric OCD is increasingly recognized as a mental health problem associated with significant morbidity in regards to psychiatric outcomes and quality of life (Bobes et al., 2001; Huppert, Simpson, Nissenson, Liebowitz, & Foa, 2009; Saxena et al., 2011). Indeed, OCD is associated with both concurrent and long-term risk for an array of comorbid mental health diagnoses; these psychiatric problems add to the burden of disease, pose their own long-term risks, and complicate the intervention landscape considerably.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely recognized as an efficacious treatment for pediatric OCD (Freeman, Garcia, et al., 2014; Geller et al., 2012; Torp, Dahl, Skarphedinsson, Compton, et al., 2015). Across more than two decades of treatment trials, CBT has demonstrated moderate-to-large effect sizes on OCD severity, as well as treatment response and remission (McGuire et al., 2015). Moreover, these benefits extend outside of specialty treatment programs and into community-based care (Torp, Dahl, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, et al., 2015). CBT for OCD is comprised of several components, which vary by protocol but typically include psychoeducation, exposure, coping skills, cognitive restructuring, and reward systems (Freeman, Sapyta, et al., 2014; Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken, & Piacentini, 2017; Piacentini et al., 2011a), although exposures are considered the core active treatment ingredient (Lewin, Wu, McGuire, & Storch, 2014).

This constellation of treatment techniques, while tailored to the unique aspects of OCD, are often found in the treatment of youth anxiety and depression. Indeed, exposures are considered the key ingredient for both OCD and anxiety (Carpenter et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2009; Piacentini et al., 2011b) and problem-solving and approach behavior (whether for exposure or behavioral activation) are prominent in anxiety and depression treatment (Weersing, Gonzalez, Campo, & Lucas, 2008; Weersing, Rozenman, Maher-Bridge, & Campo, 2012; Weersing et al., 2017).

This overlap in intervention techniques reflects both theoretical models and empirical data supporting some commonalities in the processes that underlie OCD and anxiety and depression. Given this degree of overlap, a natural question is whether treating OCD brings attendant benefits to co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms. Anxiety and depression are among the most common comorbid conditions for both youth and adults with OCD, occurring in roughly half of all individuals with a primary OCD diagnosis (Peris et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2013). The relationship between OCD and anxiety and depression symptoms is not surprising. Anxiety and depression are collectively the most common mental health problems across development (Axelson & Birmaher, 2001; Costello et al., 2003a; Merikangas et al., 2010), and co-occur with each other at very high rates (up to 88%; Harrison et al., 2009; Leyfer, Gallo, Cooper-Vince, & Pincus, 2013; Moffitt et al., 2007; Sørensen, Nissen, Mors, & Thomsen, 2005). Anxiety and depression also share underlying genetic, neurobiological, and behavioral features with one another (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004; Bird, Mansell, Dickens, & Tai, 2013; Clark & Watson, 1991; Drost et al., 2012) and with OCD (Bartz & Hollander, 2006; Carter, Pollock, Suvak, & Pauls, 2004; Graybiel & Rauch, 2000). Thus, a natural question is whether treating OCD brings attendant benefits to co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms.

However, anxiety and depression are often viewed as potential complications for OCD treatment, as clinicians may struggle with which symptoms to prioritize in session, and the symptoms themselves may interfere with an individual’s ability to participate in in-session and at-home exposures. Yet research in this area is mixed, and there are competing hypotheses about the relationship between OCD and anxiety and depression in OCD treatment. One line of thinking proposes a negative relationship between OCD treatment and anxiety/depression (Wu & Storch, 2016). For example, a natural increase in OCD symptoms early in treatment due to starting exposures and experiencing distress from response prevention efforts may lead to increases in anxiety and depressed mood. Alternatively, youth who are significantly depressed may not have sufficient motivation to practice exposure techniques and/or may not fully engage in treatment; certainly, some studies find that comorbid depressive symptoms predict worse outcome in OCD (Storch et al., 2008). Relatedly, youth who contend with anxiety symptoms may feel sufficiently fearful that they struggle to participate in at-home exposure practice. In line with this view, meta-analyses and systematic reviews indicate that anxiety and depression symptoms and diagnoses predict worse treatment outcome for both youth and adults (Turner, O’Gorman, Nair, & O’Kearney, 2018; van Balkom et al., 1994; Watson & Rees, 2008), although several individual studies have not found this to be the case (for review, see Ginsburg, Kingery, Drake, & Grados, 2008).

A contrasting hypothesis to those presented above is that learning the approach skills taught in exposure therapy may provide youth with a template for ―facing fears‖ that may in turn generalize to non-OCD anxiety symptoms (Moritz et al., 2018) and/or serve as a form of behavioral activation that improves mood (Brown, Lester, Jassi, Heyman, & Krebs, 2015). Certainly, prior studies examining the impact of CBT on anxiety and depression have found that these symptoms move in parallel, even when treatment solely targets either anxiety (Albano, Comer, Compton, et al., 2018; Carpenter et al., 2018) or depression (Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006). Similarly, meta-analytic studies have found that CBT for OCD seems to improve anxiety and depression symptoms from pre-to-post treatment (Olatunji, Davis, Powers, & Smits, 2013; Rosa-Alcázar, Sánchez-Meca, Gómez-Conesa, & Marín-Martínez, 2008), although these effects may be attenuated (i.e., anxiety/depression symptom reduction does not meet clinically significant change) as a function of treatment solely targeting OCD (Turner et al., 2018). Two CBT studies for adults with OCD have further demonstrated temporal precedence of symptom change such that OCD symptom reduction preceded and predicted depression symptom reduction, but not vice versa, (Anholt et al., 2011; Zandberg et al., 2015). This work provides preliminary support that, at least in adult patients, anxiety and depression symptoms might be expected to decrease as a function of OCD symptom improvement during CBT.

As OCD and anxiety both typically onset in childhood, and depression in adolescence, the pediatric developmental period may be a critical window within which to assess the effects of CBT for OCD on anxiety and depression symptoms. Such research may have implications for intervention for current symptoms with which the youth presents, as well as prevention of future psychopathology. Emerging work has begun to address this question directly, with three published studies testing the effects of CBT for pediatric OCD on anxiety and depression. CBT for pediatric OCD that includes a family intervention component has been found to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms from pre-to-post-treatment in one trial (N = 40; Storch et al., 2007). However, web cam-administered CBT for OCD did not outperform a wait list in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms (N=31; Storch et al., 2011). Both of these studies only assessed participants’ symptoms at pre- and post-treatment, and therefore were not able to temporally test whether OCD symptom reduction preceded and predicted anxiety and depression symptom reduction. Moreover, their findings were not consistent in regards to whether treating pediatric OCD would result in reductions in anxiety and depression. One additional study in youth demonstrated that less severe OCD symptoms significantly predicted a decrease in depressive symptoms over the course of combined CBT and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) therapy, but that week-to-week fluctuations in OCD severity during treatment did not predict weekly changes in depression symptoms (N = 56; Meyer et al., 2014). This study did not examine anxiety symptoms, even though anxiety is the most common comorbidity of pediatric OCD (Peris et al., 2017) and theoretically should respond to combination therapy in parallel alongside depression symptoms. Finally, the samples in each of these studies were relatively small; power may have been insufficient to detect effects.

In the context of this limited child literature, and with the goal of examining whether CBT for pediatric OCD results in anxiety and depression symptom improvement over time, the present study aimed to address the following questions:

Does treating pediatric OCD with manualized CBT influence the trajectory of anxiety and depression symptoms?

Are changes in anxiety and depression symptoms due to the trajectory of improvement in OCD severity or impairment over the course of treatment?

Do trajectories of anxiety and depression symptoms differ by global OCD treatment response?

Hypotheses were based on findings that targeting either anxiety or depression resulted in parallel reductions in the other set of symptoms (Albano et al., 2018; Weisz et al., 2006), and on limited findings from the adult literature suggesting that CBT for OCD produces reductions in depression (Anholt et al., 2011; Zandberg et al., 2015). In the present investigation, we predicted that anxiety and depression symptoms would improve as a function of CBT for OCD (Aim a), that this change would occur subsequent to improvements in OCD severity and impairment (Aim b) and that treatment responders would evidence a steeper slope of anxiety and depression symptom change than non-responders (Aim c).

2. Materials and method

2.1. Participants

Participating children and adolescents were aged 7 to 17 years and received 12 sessions of manualized CBT (Piacentini, Langley, & Roblek, 2007) in one of three randomized clinical trials (O’Neill et al., 2017; Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken, & Piacentini, 2017; Piacentini et al., 2011). The final sample consisted of 137 youth (Mean age = 12.23, SD = 2.80; 57% female). A small proportion (22%) of the sample self-identified as racial/ethnic minority, with 10% Hispanic/Latino, 4% Asian, 2% African American, and 6% mixed; the remainder self-identified as Caucasian (78%). Over half (52%) of the sample also met criteria for secondary Generalized, Social, or Separation Anxiety Disorder (43%), Major Depressive Disorder or Dysthymia (4%), or comorbid anxiety/depression (5%). See Table 1 for demographic and pre-treatment clinical information.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at pre- and post-treatment

| Pre-treatment | Post-Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.23 (2.80) | -- |

| Gender (% female) | 57% | -- |

| Minority status (% minority) | 22% | -- |

| Diagnostic comorbidity1 | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 43% | --2 |

| Depressive disorder | 4% | --2 |

| Anxiety and depressive disorders | 5% | --2 |

| CYBOCS total severity | 24.48 (4.36) | 13.86 (7.99) |

| CGI-I (% responder) | -- | 58% |

| COIS-RC total score | 21.57 (17.10) | 6.44 (8.98) |

| MASC total score | 50.76 (18.17) | 41.80 (17.83) |

| CDI total score | 9.83 (6.98) | 6.38 (6.11) |

Anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety, social phobia, separation anxiety; depressive disorders include major depressive disorder,

Anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses not assessed at post-treatment

2.2. Procedures

Youth were recruited from a university-based clinic; each of the clinical trials was approved by the university’s institutional review board; and families provided consent/assent prior to the initiation of any study procedures. Inclusion criteria were comparable across trials, and all youth met diagnostic criteria for primary OCD based on the same standardized assessment protocol.

The three clinical trials had the same timeline for pre- and post-treatment assessments (approximately one week after 12th CBT session, or 12 – 14 weeks after randomization), and same core assessment battery was also used to assess OCD severity, treatment response, and anxiety and depression symptoms. The studies differed in their approach to mid-treatment assessment(s) (see Table 2), which we address in the analytic plan below. Pre-treatment diagnoses, OCD severity, and global treatment response were assessed by independent evaluators (IEs) blind to youth treatment condition. IEs were masters- or doctoral-level psychologists, all of whom had extensive specialty training in the assessment of pediatric OCD and related conditions. All IE’s were trained to criterion, and participated in weekly supervision meetings. Independent ratings in two of the trials (Peris et al., 2017; Piacentini et al., 2011) found excellent inter-rater reliability for IE measures (intraclass correlation coefficients ≥ .90).‖ CBT therapists were masters- or doctoral level psychologists, supervised by individual study PIs, who are experts in the treatment of pediatric OCD.

Table 2.

Schedule of assessment in weeks in the three trials*

| Study | Pre-treatment | Mid-treatment | Post-treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| O’Neill et al., 2017 | 0 | 8 | 14 |

| Peris et al., 2017 | 0 | 6 | 12–14 |

| Piacentini et al., 2011 | 0 | 4.8 | 14 |

OCD severity (CYBOCS) and impairment (COIS-RC) were administered at each of the three assessment time points in each trial. In two of the trials (O’Neill et al., 2017; Piacentini et al., 2011) anxiety (MASC) and depression (CDI) symptoms were also administered at each of the three assessment time points; however, anxiety and depression symptoms were not assessed at mid-treatment in Peris et al., 2017.

2. 3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic information

Parents completed a demographics information sheet at pre-treatment that assessed youth age, ethnicity/race, and gender.

2.3.2. Diagnostic information

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS, Version IV; Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a semi-structured interview that assesses the major DSM-IV disorders, including OCD, anxiety disorders, and depression/dysthymia. The ADIS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001; Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002). The ADIS was administered to youth and parents by IEs at pre-treatment to confirm OCD diagnosis and to assess diagnostic comorbidities. For youth with more than one diagnosis, the ADIS clinical severity ratings were used to determine which diagnosis was primary, with primary OCD being a requirement for study entry across trials. Youth also completed a self-report of OCD-related functional impairment, and questionnaires assessing anxiety and depression symptoms, at each study assessment time point.

2.3.3. OCD severity and impairment

OCD severity was assessed with the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CYBOCS; Scahill et al., 1997), a semi-structured clinician-rated dimensional measure. The CYBOCS consists of obsession and compulsion checklists to assess specific OCD symptoms, and 10 severity items (5 for obsessions, 5 for compulsions), each rated on a 5-point scale. The CYBOCS total severity score was calculated by summing all 10 items, and was used as the primary predictor of OCD severity in analyses. The CYBOCS was administered at all three (pre-, mid-, and post-treatment) time points.

OCD-related functional impairment was assessed with the Children’s Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale – Revised, Child-Report (COIS-RC; Piacentini, Peris, Bergman, Chang, & Jaffer, 2007). The COIS-RC is a 27-item youth-report of OCD-specific functional impairment across family, academic, and social functioning, has good psychometric properties (Piacentini, Peris, et al., 2007), and is sensitive to CBT treatment response (Piacentini et al., 2011a). The COIS-RC was administered at all three (pre-, mid-, and post-treatment) time points. 2.3.4. Treatment response

The Clinical Global Impression – Improvement Scale (CGI-I; Guy, 1976) was completed by clinicians at the acute post-treatment assessment. A CGI-I rating of 1 (―very much improved‖) or 2 (―much improved‖) indicated treatment response that globally reflected reductions in OCD symptom severity and impairment.

2.3.5. Anxiety and depression symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item youth-reported questionnaire assessing anxiety symptoms across domains of social anxiety, harm avoidance/perfectionism, separation anxiety, and physical symptoms. The MASC has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in clinically anxious and community samples (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007; March et al., 1997; Wei et al., 2014). In this study, the MASC was used to track youth anxiety symptoms over the course of CBT, and was administered at pre-, mid-, and post-treatment time points (see Table 2 for exception in Peris et al., 2017).

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a 27-item youth-reported questionnaire assessing youth depression symptoms across domains of negative mood, interpersonal problems, vegetative symptoms, anhedonia, and self-esteem. The CDI has strong psychometric properties and is widely used to assess depression symptoms in clinical and community settings (Saylor & Spirito, 1984). In this study, the CDI was used to track youth depressive symptom trajectories over the course of CBT and was administered at pre-, mid-, and post-treatment time points (see Table 2 for exception in Peris et al., 2017).

2.4. Analytic Plan

Although participants in this combined dataset were drawn from clinical trials with comparable inclusion criteria and were conducted in the same research laboratory, we compared youth in the three trials on pre-treatment demographic (age, gender, % racial/ethnic minority, % on psychotropic medications at study entry) and clinical (CYBOCS total score, COIS-RC, % anxiety and depression diagnoses, MASC, CDI) variables to ensure that collapsing across trials would be appropriate. There were no differences between studies on any variables tested, including pre-treatment anxiety symptoms on the MASC (F(2,487.66)=1.48, p=.23) or pre-treatment depression symptoms on the CDI (F(2,23.15)=0.47, p=.63). The three studies also did not differ in their proportion of youth rated as treatment responders (χ2(2)=2.72, p=.26), or in CYBOCS change from pre-to-post-treatment (F(2,84.08)=0.65, p=.53).

Analyses for all three Aims were conducted in a stepwise fashion using a series of mixed models in SPSS. The MIXED procedure was selected primarily for its ability to handle nested data where the time variable varies by research study (e.g., youth from one trial had mid-treatment data at week 6, while youth from another had mid-treatment data at weeks 4 and 8). Other benefits of MIXED include its ability to handle repeated measures analysis (i.e., time-varying predictors) with non-normally distributed and missing data. Only 3% of data was missing across all time points and participants, with no differences in missingness by original trial.

In all mixed models, time was a continuous fixed effect predictor centered at zero for pre-treatment, and tested for both linear and quadratic effects, as it was unclear whether symptoms might evidence a linear slope or whether change would occur later in treatment. As the quadratic effect of time was non-significant for all models, final models herein present time as a linear effect. Subjects were entered as a random effect. Outcomes were the MASC for anxiety models and CDI for depression models. Original study source (O’Neill et al., 2017; Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken, & Piacentini, 2017; Piacentini et al., 2011) was entered as a categorical fixed effect covariate in all models in order to account for differences by study in the time and number of mid-point assessments. For Aim a, predictors included time and study source. For Aim b, one set of models assessed the time-varying impact of OCD severity and included time, CYBOCS total score, and their interaction; the other set of models assessed the time-varying impact of OCD-related impairment and included time, COIS-RC total score, and their interaction. For Aim c, predictors included time, treatment responder status (categorical yes/no), and their interaction. We planned a priori to examine the significance of slope change and, for models with significant interactions, compare estimated marginal means by time point. To conservatively control for Type II error, a family-wise alpha of .05 was set across the three Aims; only main and interaction effects which reached p=.017 (.05/3) were considered significant.

It should be noted that we also ran analyses using the MASC and CDI age- and gender-corrected t-scores; results were nearly identical with all the same significance levels as with raw scores. We elected to retain raw scores in the final Results for ease of interpretability (e.g., reduction in number of points on measures) and allow for benchmarking against raw scores in other investigations.

Based on the results, we also conducted post hoc exploratory analyses in attempts to understand change in anxiety and depression symptoms over time. Reliable change indices for anxiety and depression symptoms were calculated using Jacobson & Truax’s formula (Jacobson & Truax, 1992). T-tests and chi-square were used to compare youth evidencing reliable change in anxiety and depression symptoms on pre-treatment demographic and clinical variables.

3. Results

3.1. Aim a. Anxiety and depression symptom reduction during CBT for pediatric OCD

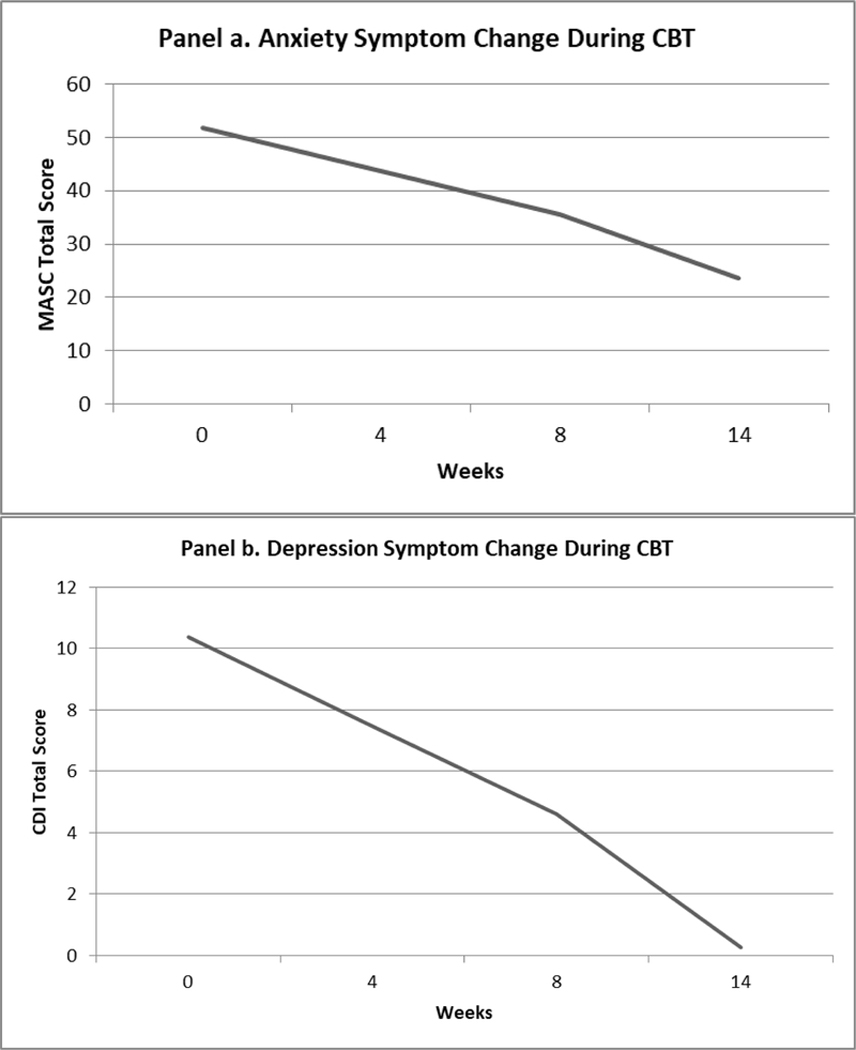

Youth anxiety and depression symptoms significantly declined during the course of CBT for pediatric OCD (Figure 1). For anxiety symptoms as measured by the MASC, there was a significant main effect of time (F (1, 197.32) = 50.94, p < .001), such that the slope of anxiety symptoms over time reflected about a two-point decrease on the MASC for every week of treatment (β = −2.01, SE = .28, t = −7.14, p < .001, CI: −2.57, −1.46). For depression symptoms, there was also a significant main effect of time (F (1, 222.84) = 33.42, p < .001), such that the slope of depressive symptoms reflected about a one-and-a-half point decrease on the CDI for every two weeks of treatment (β = −0.72, SE = .12, t = −5.78, p < .001, CI: −0.97, −0.48).

Figure 1.

Anxiety and Depression Symptom Trajectories during CBT for Pediatric OCD*

* The slope of symptom change was significant for both anxiety and depression symptoms.

CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory

3.2. Aim b. OCD severity and impairment change and anxiety/depression symptom trajectories

Anxiety symptoms.

The trajectory of anxiety symptom change was not accounted for by the trajectory of CYBOCS change over the course of CBT (F (1, 216.64) = 0.10, p = .75). There was a main effect of time (F (1,238.95) = 4.79, p = .030), indicating that anxiety symptoms decreased over time, and a main effect of OCD severity (F (1, 212.80) = 23.53, p < .001) suggesting that pre-treatment CYBOCS was positively correlated with pre-treatment anxiety symptoms. Anxiety symptom change was also not accounted for by reductions in OCD-related impairment (COIS-RC; F (1, 123.34) = 1.43, p = .23). Again there was a main effect of time (F (1, 106.60) = 19.53, p < .001), but no main effect of the COIS-RC (F (1, 41.37) = 3.29, p = .077).

Depression symptoms.

The trajectory of depression symptom change was not explained by the trajectory of CYBOCS change over the course of CBT (F (1, 241.25) = 0.57, p = .45). As with anxiety reduction, there was a main effect of time (F (1, 277.44) = 57.76), p < .001) but no main effect of CYBOCS (F (1, 265.91) = 0.01), p = .96). Similarly, depression symptom change was not accounted for by reductions in OCD-related impairment (COIS-RC F (1, 100.03) = 0.54, p = .46), with a main effect of time (F (1, 103.56) = 13.40, p < .001) and a main effect of OCD-related impairment (F (1, 57.48) = 9.49, p = .003).

3.3. Aim c. Anxiety/depression symptom trajectories by treatment response

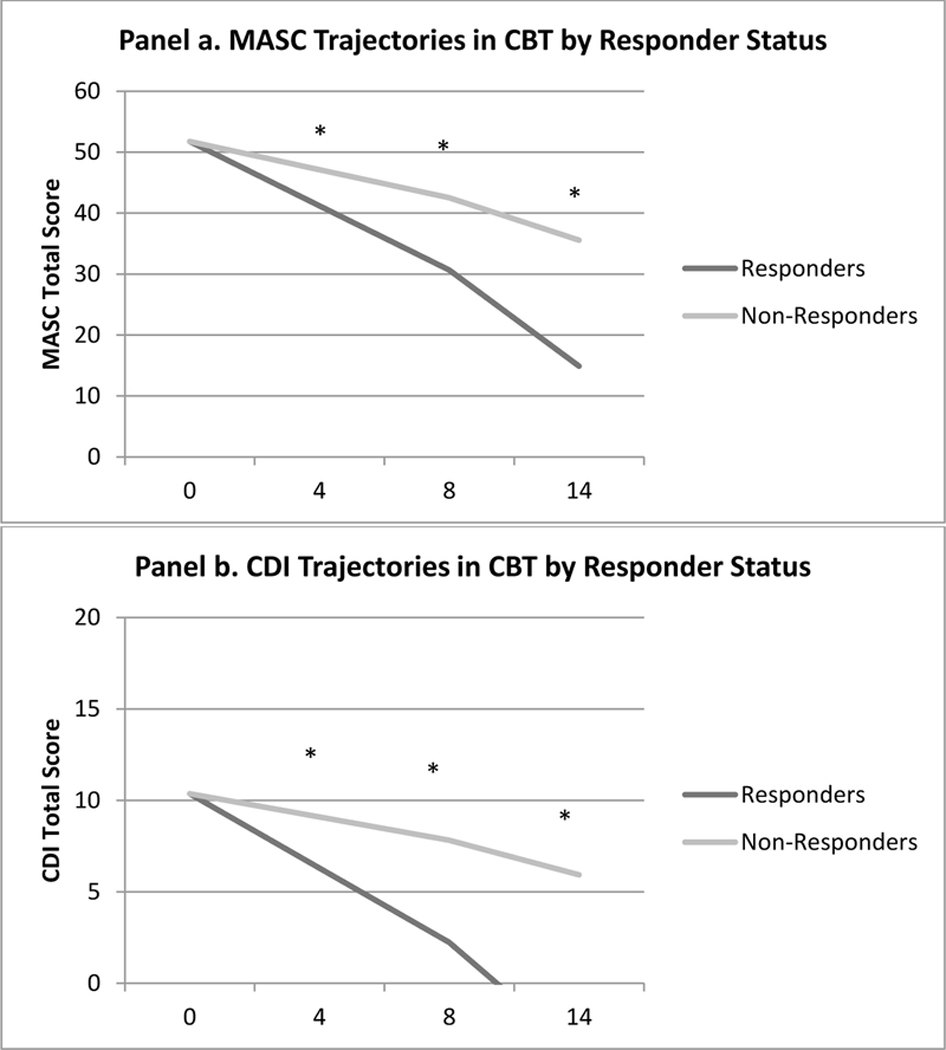

CBT treatment responders and non-responders did not significantly differ in their levels of pre-treatment anxiety (t = 0.43, p = .67) or depression (t = 0.91, p = .36) symptoms. However, symptom trajectories of both anxiety and depression differed by OCD treatment responder status over the course of the CBT. For anxiety, a significant treatment response x time interaction (F (1, 249.75) = 10.62), p = .001) revealed that, compared to non-responders, treatment responders demonstrated a steeper slope of anxiety reduction over the course of CBT (β = −1.48, SE = .45, t = −3.26, p = .001, CI: −2.37, −0.58). Examination of estimated marginal means revealed that, as early as week 4, responders had significantly lower anxiety symptoms than non-responders, and continued to evidence significantly lower anxiety than non-responders for the remainder of treatment (Figure 2, Panel a). In parallel, a significant treatment response x time interaction emerged for depression symptoms (F (1, 258.51) = 13.48, p < .001), such that treatment responders demonstrated steeper slope of depression symptom reduction over the course of CBT (β = −0.70, SE = .19, t = −3.67, p < .001, CI: −1.07, −0.32). Examination of estimated marginal means revealed that, as early as week 4, treatment responders evidenced significantly lower depression symptoms than non-responders, and continued to do so for the remainder of treatment (Figure 2, Panel b). However, further attempts to test interactions between treatment response and OCD severity or impairment trajectories did not result in additional significant interactions.

Figure 2.

Anxiety and Depression Symptom Trajectories by Responder Status during CBT for Pediatric OCD

CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; Responders = Post-Treatment CGI-I ≤ 2; Non-Responders = Post-Treatment CGI-I >2

* indicates significant group differences in estimated marginal means by time point

3.4. Exploratory Analyses: Reliable Clinical Change

In an attempt to further understand the relationship between treatment response and anxiety/depression symptoms – particularly as it was not accounted for by improvements in OCD severity or impairment – one additional set of post hoc exploratory analyses was conducted. The Reliable Change Index (Jacobson & Truax, 1992) was calculated for both the MASC and CDI from pre-to-post–treatment to examine the proportion of youth for whom symptom reduction represented a substantial clinical change (RCI > 1.96). Raw score normative data used to measure the RCI for the MASC comprised a standard deviation of 14 (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007) and a test-retest reliability of .79 (March et al., 1997), and for the CDI comprised a standard deviation of 7.04 (Smucker, Craighead, Craighead, & Green, 1986) and a test-retest reliability of .81 (Figueras Masip, Amador-Campos, Gómez-Benito, & del Barrio Gándara, 2010).

Anxiety RCI.

Reliable clinical change occurred for 34% of all youth on the MASC, and a significantly greater proportion of post-treatment responders achieved reliable clinical change on the MASC than non-responders (42% vs. 29%; χ2(1) = 5.41, p = .02). Youth who achieved reliable clinical change on the MASC did not differ from their counterparts who did not achieve reliable clinical change in age (t = .57, p = .57), gender (χ2(1) = 0.09, p = .76), or on any of the following pre-treatment clinical features: OCD severity (t = 1.11, p = .27), OCD-related impairment (t = −0.97, p = .33), depression symptoms (t = −1.71, p = .09), or presence of anxiety (χ2(1) = 1.73, p = .19) or depression (χ2(1) = 0.22, p = .64) diagnoses. However, youth who evidenced reliable clinical change on the MASC had higher pre-treatment MASC scores (Mean = 60.16, SD = 15.32) than those who did not achieve reliable change (M = 45.73, SD = 18.14, t = −4.73, p < .001).

Depression RCI.

Reliable clinical change occurred for 24% of youth on the CDI. The proportion of responders and non-responders who achieved reliable clinical change on the CDI from pre-to-post-treatment did not significantly differ (29% vs. 17%; χ2(1) = 2.52, p = .11). Youth who achieved reliable clinical change on the CDI did not differ from their counterparts who did not achieve reliable clinical change in age (t = −0.20, p = .85), gender (χ2(1) = 0.72, p =.40), or on any of the following pre-treatment clinical features: OCD severity (t = −0.94, p = .41), OCD-related impairment (t = 1.12, p = .24), or presence of anxiety diagnosis (χ2(1) = 0.44, p = .51). However, youth who evidenced reliable clinical change in depression symptoms from preto-post treatment had higher symptom scores than their counterparts who did not evidence reliable clinical change on pre-treatment anxiety symptoms (M = 61.37, SD = 16.64 vs. M = 47.32, SD = 17.92, t = −3.97, p < .001), pre-treatment depression symptoms (M = 17.00, SD = 7.43 vs. M = 7.72, SD = 5.38, t = −6.35, p < .001). Youth who evidenced reliable clinical change in depression symptoms also had higher rates of depressive disorder diagnoses (23%) than those who did not evidence reliable clinical change (4%; χ2(1) = 10.69, p < .001).

4. Discussion

Pediatric OCD occurs commonly with other forms of youth psychopathology (Geller et al., 2001; Peris et al., 2017), and an important question for both clinicians and researchers is how treatment of one condition affects the others. The overarching goal of this study was to examine trajectories of symptom change for two of the most common comorbidities, anxiety and depression, over the course of CBT for pediatric OCD. Drawing on a large, well-characterized sample of treatment-seeking youth, we found support for our hypothesis that both anxiety and depression symptoms would improve over the course of OCD treatment. Likewise, we also found support for the hypothesis that CBT treatment responders would demonstrate steeper slopes of improvement in anxiety and depression compared to their non-responding counterparts. Counter to expectations, these improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms were not accounted for by changes in OCD symptom severity or impairment.

CBT for OCD encompasses a range of techniques, including psychoeducation, exposure, and cognitive restructuring, which collectively are intended to help youth face feared situations, test hypotheses about feared situations, and develop more adaptive coping skills. It is encouraging to see evidence that these techniques may carry additional benefit for secondary conditions, even when they are not directly targeted in treatment. Indeed, among youth with OCD who responded to CBT, secondary symptom improvement was evident as early as the fourth week of treatment. These findings offer good news for patients and providers alike, insomuch as they point to benefits of exposure-based CBT that may extend beyond target symptoms of OCD. They are particularly interesting given that, in this treatment protocol, youth had only had two sessions of exposure at the week 4 assessment period. Indeed, although the mechanism is unclear, soon after the transition from psychoeducation and symptom hierarchy development to skills training (i.e., the practice of confronting fears), there may be a global lifting of disease burden.

Notably, although both anxiety and depression improved over the course of treatment, there seemed to be particular benefit for anxiety such that there appeared to be a steeper slope of change over time in anxiety symptoms and a larger proportion of youth evidencing reliable clinical change in symptoms from pre-to-post-treatment (34% for anxiety, 24% for depression). One explanation for this may be that exposure-based CBT for OCD is similar to that for anxiety in its emphasis on exposure tasks, and less similar to CBT for depression (which involves behavioral activation/pleasant activity scheduling, and may also involve other skills such as communication and problem solving). As might be expected based on clinical anecdote and data supporting more similarities between pediatric OCD and anxiety than OCD and depression, CBT for OCD may provide youth and families with tools that more readily generalize to anxiety versus depression. It may also be the case that symptoms of depression take longer to address. To the extent that the average age of OCD onset occurs prior to depression during the pediatric period (Costello et al., 2003), and that depression occurs secondary to OCD (Bartz & Hollander, 2006), youth may need more time to experience relief from OCD symptoms and impairment before related feelings of low mood attenuate.

Interestingly, we did not find support for the hypothesis that changes in anxiety and depression symptomatology would be linked to the course of improvement in OCD severity and impairment. This finding is inconsistent with prior findings in the adult literature (Anholt et al., 2011; Zandberg et al., 2015), and with theories that OCD drives anxiety and depression symptoms, and that directly targeting OCD symptoms leads to downstream change in anxiety and depression (e.g., Brown et al., 2015). Given that anxiety and depression symptoms demonstrated greater improvements for treatment responders than non-responders, it is unclear whether treatment responders evidenced benefit in anxiety and depression symptoms because their OCD symptoms improved sufficiently to be rated as achieving treatment response, or because something about CBT more generally was beneficial for their anxiety/depression symptoms and OCD symptoms simultaneously.

It is also important to note that youth who achieved reliable clinical change in anxiety and depression symptoms were more likely to have elevated symptoms at pre-treatment. It may be the case that anxiety and depression symptoms index global distress for some youth, which attenuates more rapidly as they seek help and gain a sense of hope. Moreover, youth who obtained reliable clinical change in depression symptoms also had elevated anxiety/depression symptoms and diagnoses compared to their counterparts who did not evidence reliable clinical change. We are enthused by this finding, as it suggests that youth with elevated depression symptoms and anxiety/depression diagnoses have the potential to achieve significant improvement in their depression symptoms by participating in CBT for OCD.

Together, the present results raise questions about what, if not reductions in OCD severity or impairment, drives anxiety and depression symptom reduction, as well as how to better treat OCD-affected youth with anxiety and/or depression symptoms who do not respond to CBT. Clearly, although considerable overlap in OCD and anxiety/depression symptoms exists, the need to understand unique elements of the processes underlying these mental health problems and how to effectively and efficiently target them in treatment remains. Given the heterogeneous symptom presentations of each of these conditions and some proposed underlying mechanisms that do not overlap between them, treatment packaging and tailoring may be especially relevant based on specific comorbid clinical presentations and/or likelihood to respond to psychosocial intervention. For example, modular, sequenced, or stepped approaches (e.g., Van Der Leeden et al., 2011) might be utilized such that OCD symptoms are prioritized and anxiety/depression symptoms subsequently addressed if necessary, which likely mimics what commonly happens in clinical practice. Sequencing may also allow for prioritization of depression symptoms if they interfere with in- or out-of-session exposure compliance. Evidence from the anxiety and depression literatures across youth (Weersing et al., 2017) and adults (Andersen, Toner, Bland, & McMillan, 2016; Newby, McKinnon, Kuyken, Gilbody, & Dalgleish, 2015) support additional testing of trasndiagnostic interventions. Such treatments may teach a core set of techniques consisting of global approach behavior (i.e., exposure and behavioral activation) in combination with problem-solving skills that might be particularly useful for youth with anxieyt/depression sypmtoms that are co-primary with their OCD or are severe enough to interfere with traditional ERP. In addition, practice parameters for the treatment of OCD (Geller et al., 2012) and anxiety (Connolly & Bernstein, 2007) and depression ( Brent et al., 2007) in youth recommend a combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy for moderate-to-severe presentations and/or when one approach is insufficient; it is noteworthy that SSRIs are front-line pharmacotherapy approaches across these conditions. Additional research examining anxiety and depression trajectories in concert with pediatric OCD trajectories in the context of these intervention modalities may provide invaluable information regarding how to best address these symptoms in the context of pediatric OCD treatment.

The present findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms over time could be due to several alternate factors including regression to the mean, low pre-treatment depression scores resulting in a floor effect, non-specific therapeutic factors such as face-to-face time with and support from a mental health professional, or reporter bias as a function of multiple measurements (particularly given that youth were not blind to treatment condition). Relatedly, anxiety and depression symptom ratings were only provided by youth; parallel parent and blind evaluator reports of anxiety and depression symptoms would have increased confidence in results. Next, anxiety and depression diagnoses were not assessed at post-treatment, so we are not able to speak to whether anxiety and depression diagnoses remitted alongside OCD response. Future studies might use blind evaluators to assess OCD, anxiety, and depression symptoms and diagnoses over the course of CBT to address these limitations. Our methods are also limited by the way in which our sample was ascertained (based on primary OCD diagnosis), which does not permit inferences about youth with primary anxiety or major depressive disorder, and secondary OCD, nor provide for a more full range of comorbid anxiety and depression symptom severity. Finally, the current sample was primarily Caucasian, which may limit our ability to generalize these findings to minority youth.

5. Conclusions

The present study found that youth with a primary diagnosis of OCD experienced reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms over the course of CBT treatment, and that, overall, this change was more marked for youth who responded favorably to treatment. At the same time, reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms were not due to improvements in OCD severity or impairment, raising important questions about the mechanisms underlying these treatment gains. As OCD, anxiety, and depression symptoms and diagnoses co-occur at high rates, and each are considered chronic conditions that pose considerable long-term risk to youth, more research is needed to understand how best to address their co-occurrence. Future studies might examine treatment-sequencing approaches to target both OCD and comorbid anxiety/depression with the goal of moving youth from functional impairment into wellness, as well as whether improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms are maintained over time and/or track with OCD symptoms longitudinally following treatment.

Highlights.

Anxiety and depression often co-occur in pediatric OCD

Both anxiety and depression symptoms declined over the course of CBT for children and adolescents with primary OCD

Reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms was not linked to specific improvements in OCD sevesrity or impairment

Youth who responded to CBT for their OCD symptoms also experienced significant reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms compared to treatment non-responders

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the youths and families who participated in this research.

Funding: Support for this manuscript was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH058459, R01MH081864, K23MH085058) and the UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute (KL2 UL1TR000124).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures (unrelated to work on this manuscript): Dr. Rozenman reports no financial disclosures or grant support unrelated to work on this manuscript. Drs. Piacentini, Peris, Bergman and Chang have received royalties from Oxford University Press, including for manual for the CBT described in this study. Dr. Piacentini has also received royalties from Guilford Press and the American Psychological Association, and has served on the speakers’ bureau for the TSA. Drs. Piacentini, Chang, O’Neill and Peris report grant support from NIMH unrelated to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albano AM, Comer JS, Compton SN, Piacentini J, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Walkup JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Keeton C, 2018. Secondary outcomes from the child/adolescent anxiety multimodal study: Implications for clinical practice. Evid. Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 3(1), 30–41. doi: 10.1080/23794925.2017.1399485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Toner P, Bland M, McMillan D, 2016. Effectiveness of transdiagnostic cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and depression in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 44(6), 673–690. doi: 10.1017/S1352465816000229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anolt GE, Aderka IM, Van Balkom AJ, Van Balkom AJLM, Smit JH, Hermesh H, De Haan E, Van Oppen P, 2011. The impact of depression on the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Results from a 5-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 135, 201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexson DA, Birmaher B, Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2001. Depress. Anxiety 14(2), 67–78. doi: 10.1002/da.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JS, Dadds MR, 2007. Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 46(2), 252–260. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML, 2004. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behav. Ther. 35(2), 205–230. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80036-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz JA, Hollander E, 2006. Is obsessive-compulsive disorder an anxiety disorder? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 30(3), 338–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird T, Mansell W, Dickens C, Tai S, 2013. Is there a core process across depression and anxiety? Cogn. Ther. Res. 37(2), 307–323. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9475-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobes J, González MP, Bascarán MT, Arango C, Sáiz PA, Bousoño M, 2001. Quality of life and disability in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 16(4), 239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00571-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HM, Lester KJ, Jassi A, Heyman I, Krebs G, 2015. Paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder and depressive symptoms: Clinical correlates and CBT treatment outcomes. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43(5), 933–942. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9943-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG, 2018. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress. Anxiety 35(6), 502–514. doi: 10.1002/da.22728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Pollock RA, Suvak MK, Pauls DL, 2004. Anxiety and major depression comorbidity in a family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress. Anxiety 20(4), 165–174. doi: 10.1002/da.20042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, 1991. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1003, 316–336. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.1003.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SD, Bernstein GA, 2007. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 46(2), 267–283. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246070.23695.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A, 2003. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60(8), 837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drost J, Der Does AJW, Antypa N, Zitman FG, Van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, 2012. General, specific and unique cognitive factors involved in anxiety and depressive disorders. Cognit. Ther. Res. 36(6), 621–633. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9401-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masip AF, Amador-Campos JA, Gómez-Benito J, del Barrio Gandara V, 2010. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Inventory in community and clinical sample. Span. J. Psychol. 13(2), 990–999. doi: 10.1017/S1138741600002638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JB, Choate-Summers ML, Garcia AM, Moore PS, Saptya JJ, Khanna MS, March JS, Foa EB, Franklin ME, 2009. The pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment study II: Rationale, design, and methods. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 3(1), 4–19. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Garcia A, Frank H, Benito K, Conelea C, Walther M, Edmunds J, 2014. Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 43(1), 7–26. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.804386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, Compton S, Khanna M, Flessner C, FitzGerald D, Mauro C, Dingfelder R, Benito K, Harrison J, Curry J, Foa E, March J, Moore P, Franklin M, 2014. Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment study for young children (POTS jr)—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 71(6), 689–698. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA, March J, AACAP Committee on Quality Issues, 2012. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51(1), 98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Kingery JN, Drake KL, Grados MA, 2008. Predictors of treatment response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 47(8), 868–878. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799ebd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Rauch SL, 2000. Toward a neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuron 28(2), 343–347. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00113-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, 1976. Clinical Global Impression Scale. Psychopharmacol. Rev. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Pujol J, Ortiz H, López-Solà M, Hernández-Ribas R, Dues J, Alonso P, Yücel M, Pantelis C, Menchon JM, Cardoner N, 2009. Altered corticostriatal function connectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66(11), 1189–2000. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, Liebowitz MR, Foa EB, 2009. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress. Anxiety 26(1), 39–45. doi: 10.1002/da.20506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Traux P, 1992. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. (59)1, 12–19. doi: 10.1037/10109-042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, 1985. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 21(4), 995–998. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.01004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin AB, Wu MS, McGuire JF, Storch EA, 2014. Cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 37(3), 415–445. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyfer O, Gallo KP, Cooper-Vince C, Pincus DB, 2013. Patterns and predictors of comorbidity of DSM-IV anxiety disorders in a clinical sample of children and adolescents. J. Anxiety Disord. 27(3), 306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, James MPH, Sullivan K, Stallings P, 1997. The multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC): Factor, structure, reliability, and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36(4), 554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Lewin AB, Brennan EA, Murphy TK, Storch EA, 2015. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and medication for child obsessive compulsive disorder: Moderators of treatment efficacy, response, and remission. Depress. Anxiety 32(8), 580–593. doi: 10.1002/da.22389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J, 2010. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication—adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 49(10), 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JM, McNarmara JPH, Reid AM, Storch EA, Geffken GR, Mason DM, Murphy TK, Bussing R, 2014. Prospective relationship between obsessive-compulsive and depressive symptoms during multimodal treatment in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 45(2), 163–172. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0388-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Caspi A, Kim-Cohen J, Goldberg D, Gregory AM, Poulton R, 2007. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(6), 651–660. doi: 10.1001/archpsych.64.8.651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortiz S, Fink J, Miegel F, Nitsche K, Kraft V, Tonn P, Jelinek L, 2018. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is characterized by a lack of adaptive coping rather than an excess of maladaptive coping. Cogn. Ther. Res. 42(5), 650–660. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9902-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, McKinnon A, Kuyken W, Gilbody S, Dalgleish T, 2015. Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 40, 91–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J, Piacentini J, Chang S, Ly R, Lai TM, Armstrong CC, Bergman L, Rozenman M, Peris T, Vreeland A, Mudgway R, Levitt JG, Salamon N, Posse S, Hellemann GS, Alger JR, McCracken JT, Nurmi EL, 2017. Glutamate in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder and response to cognitive-behavioral therapy: Randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 42(12), 2414–2422. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, 2013. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47(1), 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis TS, Rozenman M, Bergman RL, Chang S, O’Neil J, Piacentini J, 2017. Developmental and clinical predictors of comorbidity for youth with obsessive compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 93, 72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Rozenman MS, Sugar CA, McCracken JT, Piacentini J, 2017. Targeted Family Intervention for Complex Cases of Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56 (12), 1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j/jaac.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Chang S, Langley A, Peris T, Wood JJ, McCracken J, 2011. Controlled comparison of family cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation/relaxation training for child obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50(11), 1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Langley A, Roblek T, 2007. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of childhood OCD: It’s only a false alarm: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, Jaffer M, 2007. Functional impairment in childhood OCD: Development and psychometrics properties of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R). J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 36(4), 645–653. doi: 10.1080/15374410701662790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Alcazar AI, Sanchez, Meca J, Gomez, Conesa A, Martin-Martinez F, 2008. Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28(8), 1310–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Ayers CR, Maidment KM, Vapnik T, Wetherell JL, Bystritsky A, 2011. Quality of life and functional impairment in compulsive hoarding. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45(4), 475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Spirito A, 1984. The Children’s Depression Inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 52(6), 955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.52.6.955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, Leckman JF, 1997. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36(6), 844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano A, 1996. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Parent interview schedule. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Saavedra LM, Pina AA, 2001. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40(8), 937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ, 1986. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. J Abnorm. Child Psychol. 14(1), 25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen MJ, Nissen JB, Mors O, Thomsen PH, 2005. Age and gender differences in depressive symptomatology and comorbidity: An incident sample of psychiatrically admitted children. 84(1), 85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SE, Mayerfeld C, Arnold PD, Crane JR, O’Dushlaine C, Fagerness JA, Yu D, Scharf JM, Chan E, Kassam F, Moya PR, Wendland JR, Delorme R, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Saumuels J, Greensberg BD, McCracken JT, Knowles JA, Fyer AJ, Rauch SL., Riddle MA, Bienvenu OJ, Cullen B, Wang Y, Shugart YY, Piacentini J, Rasumssen S, Nestadt G, Murphy DL, Jenike MA, Cook EH, Pauls DL, Hanna GL, Mathews CA, 2013. Meta-analysis of association between obsessive-compulsive disorder and the 3’ region of neuronal glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 162B(4), 367–379.doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Caporino NE, Morgan JR, Lewin AB, Rojas A, Brauer L, Larson MJ, Murphy TK, 2011. Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 189(3), 407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ, Mann G, Duke D, Munson M, Adkins J, Grabill KM, Murphy TK, Goodman WK, 2007. Family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Comparison of intensive and weekly approaches. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 46(4), 469–478. doi: 10.1097/chi.obo13e31803062e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp NC, Dahl K, Skarphedinsson G, Compton S, Thomsen PH, Weidle B, Hybel K, Nissen JB, Ivarsson T, 2015. Predictors associated with improved cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54(3), 200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp NC, Dahl K, Skarphedinsson G, Thomsen PH, Valderhaug R, Weidle B, Melin KH, Hybel K, Nissen JB, Lenhard F, Wentzel-Larsen T, Franklin ME, Ivarsson T, 2015. Effectiveness of cognitive behavior treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Acute outcomes from the Nordic Long-term OCD Treatment Study (NordLOTS). Behav. Res. Ther. 64, 15–23. doi: 1016/j.brat.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C, O’Gorman B, Nair A, O’Kearney R, 2018. Moderators and predictors of response to cognitive behaviour therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 261, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Balkom AJLM, Van Oppen P, Vermeulen AWA, Van Dyck R, Nauta MCE, Vorst HCM, 1994. A meta-analysis on the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: A comparison of antidepressants, behavior, and cognitive therapy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 14(5), 359–381. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(94)30033-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Leeden AJ, Van Widenfelt BM, Van Der Leeden R, Liber JM, Utens EM, Treffers PD, 2011. Stepped care cognitive behavioural therapy for children with anxiety disorders: A new treatment approach. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 39(1), 55–75. doi: 10.1017/S7352465810000500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson HJ, Rees CS, 2008. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled treatment trials for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 43(5) 489–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Brent DA, Rozenman MS, Gonzalez A, Jeffreys M, Dickerson JF, Lynch FL, Porta G, Iyengar S, 2017. Brief behavioral therapy for pediatric anxiety and depression in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 74(6), 571–578. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Gonzalez A, Campo JV, Lucas AN, 2008. Brief behavioral therapy for pediatric anxiety and depression: Piloting an integrated treatment approach. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 15(2), 126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2007.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Rozenman MS, Maher-Bridge M, Campo JV, 2012. Anxiety, depression, and somatic distress: Developing a transdiagnostic internalizing toolbox for pediatric practice. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 19(1), 68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cbora.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Hoff A, Villabo MA, Peterman J, Kendall PC, Piacentini J, McCracken J, Walkup JT, Albano AM, Rynn M, Sherrill J, Sakolsky D, Birmaher B, Ginsburg G, Keeton C, Gosch E, Compton SN, March J, 2014. Assessing anxiety in youth with Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 43(4), 566–578. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM, 2006. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 123(1), 132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V, 2002. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 31(3), 335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP310305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MS, Storch EA, 2016. Personalizing cognitive-behavioral treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Exper. Rev. Precis. Med. Drug. Develop. 1(4), 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Zandberg LJ, Zang Y, McLean CP, Yeh R, Simpson HB, Foa EB, 2015. Change in obsessive-compulsive symptoms mediates subsequent change in depressive symptoms during exposure and response prevention. Behav. Res. Ther. 68, 76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar AH, 1999. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 8(3), 445–460. doi: 10.1016/S10564993(18)30163-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]