Abstract

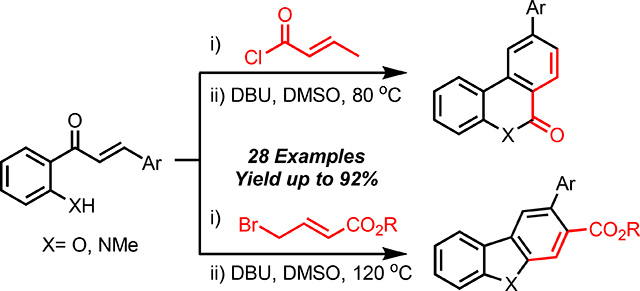

A metal-free aromative cascade has been developed for the synthesis of diverse heterocycles from readily accessible hydroxy/aminochalcones and acid/alkyl halides. The cascade being by a base-mediated intramolecular aldol cyclization/dehydration sequence to provide a triene, which sets the stage for a 6π-electrocyclization/oxidative aromatization to access diverse heterocyclic scaffolds.

Graphical Abstract

A unique retrosynthetic disconnection to diverse heterocyclic scaffolds using 6 -electrocyclization strategy

Cascade reactions are an elegant strategy for assembling molecular complexity in organic synthesis.1 Furnishing high efficiency and atom economy, cascade reactions use multiple transformations in a one-pot fashion.2 Employing cascade reactions as an approach eases reaction workup, purification, time, and waste management.3 These advantages altogether make cascade reactions ideal for green chemical synthesis.4

In continuing our work on cascade approaches to medium-sized scaffolds,5 we designed a metal-free cascade comprised of an intramolecular aldol reaction/anionic oxy-Cope rearrangement to furnish 10-membered lactones (Scheme 1a). The cascade precursor is readily accessible through the standard coupling of hydroxychalcones to unsaturated acids. However, when we exposed precursor 1 (R=Me) to basic conditions, we recovered a complex mixture of products. We suspected that the additional methyl group was dissuading the desired enolization, leading to ketene formation and subsequent fragmentation of the hydroxychalcone component.6 When the methyl group was removed (R=H), we did not observe any trace of desired macrolactone, but small quantities of the aromatized benzo[c]coumarin 3, which presumably formed via an intramolecular 6π-electrocyclization of 1,3,5-triene 2 (Scheme 1b).7

Scheme 1.

a) Anionic oxy-Cope approach to 10-membered macrolactones. b) Serendipitous approach to benzo[c]coumarins.

Although there are examples in literature of 6π-electrocyclization employed in the synthesis biologically relevant natural products,8 this serendipitous cascade represents a unique approach for the construction of functionalized benzo[c]coumarins that does not rely on modification of a pre-formed coumarin scaffold.9

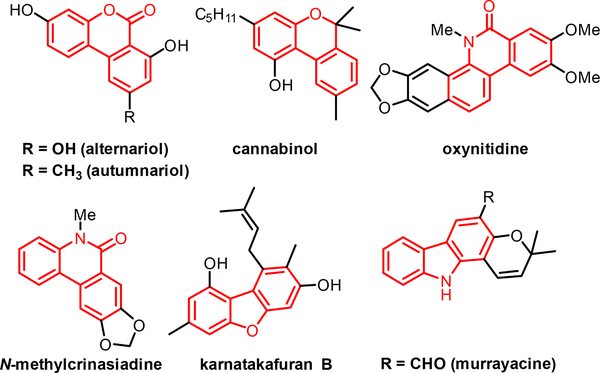

Inspired by these results, we envision applying this approach to the synthesis of heterocyclic scaffolds, which are found in numerous natural products and drug molecules. In particular, the benzo[c]coumarin core can be found in several natural products, and was recently used as a precursor to access the cannabinoid receptor agonist cannabinol.10d In addition, the related heterocycles such as phenanthridin-6(5H)-ones, dibenzofurans, and carbazoles are also commonly found in nature and medicinally relevant compounds (Fig. 1).10

Fig. 1.

Aromatic heterocycles in natural products.

Although there are multiple methods currently available in literature for the synthesis of these heterocycles, most rely on the use of transition metal catalysts.11 With high cost and difficult purification, reducing the use of expensive transition metal catalysts in chemical reactions is a unifying goal in the synthetic community.12 Keeping these advantages in mind, our serendipitous cascade is attractive and provides an alternative metal-free method for the synthesis of aromatic heterocycles.

We commenced our reaction optimization for the formation of benzo[c]coumarin 3. When precursor 1 was exposed to K2CO3 in refluxing acetone for 16 hours, we observed complete conversion of 1 to triene 2, with further conversion to 3 (Table 1, entry 1). These reaction conditions however resulted in a low overall yield of 3. We then attempted the reaction utilizing organic bases, beginning with Et3N. After 16 hours of stirring at reflux temperature in dichloromethane, we observed no conversion to triene 2 and pure 1 was recovered (entry 2). When a stronger base (DBU) was utilized, we then observed full conversion of 1 to furnish a mixture of 2 and 3 (entry 3). Inspired by recent reports into the 6π-electrocyclization of 1,3,5-triene systems,9 DMSO was employed as the reaction solvent, and improved conversion of 2 to 3 was observed (entry 4). When the reaction was heated to 80 oC in DMSO, full conversion of 2 to 3 was observed, with an isolated yield of 82% (entry 5).

Table 1.

Reaction optimization for aldol elimination/ electrocyclization sequence.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Base (equiv.) | Solvent | Temp. | 2/3b |

| 1 | K2CO3 (3.0) | Acetone | reflux | 1:2 (23)c |

| 2 | Et3N (3.0) | DCM | reflux | N.R. |

| 3 | DBU (3.0) | DCM | rt | 95:5 |

| 4 | DBU (3.0) | DMSO | rt | 90:10 |

| 5 | DBU (3.0) | DMSO | rt → 80 °C | 0:100 (82)c |

| 6 | DBU (2.0) | DMSO | rt → 80 °C | 0:100 (64)c |

| 7 | DBU (1.0) | DMSO | rt → 80 °C | 0:100 (45)c |

| 8 | DBU (0.1) | DMSO | rt → 80 °C | trace |

All optimization reactions were performed by adding base at room temperature to a solution of 1 in DMSO (0.15 M). The reaction vessel was sealed and heated at the indicated temperature for 16 hours.

The percent ratio of 2 and 3 was determined by crude 1H NMR integration.

Isolated yield of 3 obtained after column chromatography.

N.R. = No reaction

The reaction was also successful using lower quantities of base, however a notable decrease in the isolated yield was observed (entries 6 and 7) with a longer reaction time. When 0.1 equivalents of base was utilized, incomplete conversion of 1 was observed, and 3 was obtained in trace quantity (entry 8).

With optimized conditions in hand, we then turned our attention towards the substrate scope for this cascade (Fig. 2). The reaction was amenable to substituents on the pre-existing aromatic ring, resulting in good yields for compounds 3b and 3c. Next, we explored the electronic influence of the triene on the overall reaction cascade. Electron- neutral and electron-donating substituents were well-tolerated and resulted in good to excellent yields (3d-3f). The reaction though was low-yielding with trifluoromethyl substituted compound 3g. Reaction conditions were also tolerant of other heterocycles comprising the chalcone component, and furan-substituted 3h was synthesized in good yields. Finally, A lower yield was observed for methyl-substituted compound 3i, and in this instance we observed byproducts arising from incomplete electrocyclization in the crude NMR.

Fig. 2.

Scope of benzo[c]coumarin substrate examples; all reactions were performed by adding DBU (3.0 equiv) to a 0.15 M solution of 1 (1.0 equiv) in DMSO at room temperature. After stirring for 90 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was heated to 80 oC for 16 hours. aReaction was also performed at 1-gram scale with an isolated yield of 76%.

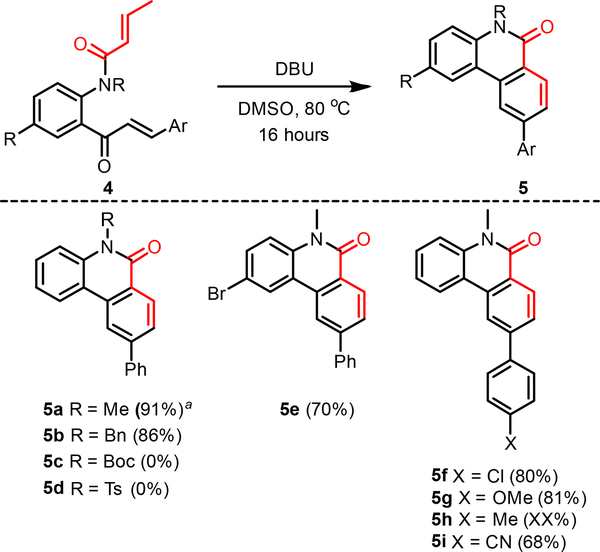

Addressing a limitation in some of the current electrocyclization-based methods for benzo[c]coumarin formation, we wondered if our method was suitable for synthesizing their nitrogen analogues, phenanthridin-6(5H)-ones (Fig. 3).9a By coupling N-alkylaminochalcones to crotonyl chloride, we were able to access precursors 4 in a three-step sequence. Parent compound 5a was synthesized in excellent yields, and notably, was suitable to a 1-gram scale-up, with only a slight decrease in overall yield (89%). The reaction also tolerated other N-protecting groups well, with benzyl-protected 5b synthesized in comparable yields. Alkyl protection of the amide was crucial to the success of this reaction however; when the free N-H amide was exposed to the optimized DBU heating conditions, a complex mixture of products was recovered. Similarly, the reaction conditions were not suitable for the common nitrogen protecting groups tert-butylcarbamate (boc) and tosyl group.13 In both cases, cleavage of the crotonylamide bond was observed at room temperature, resulting in recovery of the corresponding aminochalcone precursor.

Fig. 3.

Scope of phenanthridin-6(5H)-one substrate examples; all reactions were performed by adding DBU (3.0 equiv) to a 0.15 M solution of 1 (1.0 equiv) in DMSO at room temperature. After stirring for 90 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was heated to 80 oC for 16 hours. aReaction was also performed at 1-gram scale with an isolated yield of 89%.

Like their oxygen-containing counterparts, the cascade was tolerant of electron-neutral and electron-donating substituents (5f-5h). Again, we observed diminished yields with electron-withdrawing substituents, with cyano-substituted 5i synthesized in only moderate yields. We observed higher yields overall for the synthesis of these phenanthridin-6(5H)-ones, presumably due to the disfavoured ketene-mediated fragmentation of 4, relative to 1, in the presence of a strong base.6

A plausible reaction mechanism for this cascade is depicted in scheme 2. First, γ-deprotonation of crotonate A generates enolate B which undergoes α-enolate attack onto the ketone followed by the loss of water to generate 1,3,5-triene C. Under heating conditions, triene C can perform a 6π-electrocyclization forming D, which is capable of aromatization via an aerial oxidation,14 generating benzocoumarin or phenanthradinone E.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of Benzo[c]coumarins.

Several experiments were performed to validate the proposed reaction mechanism. We were able to isolate triene C after 90 minutes of stirring at room temperature in the presence of DBU. When triene C is exposed to the same DBU conditions while heating to 80 oC for 16 hours, E is obtained in good yields supporting our proposal that it is an intermediate in this process. It was also found that the addition of the single electron oxidant DDQ can promote the oxidation of D to E. We then probed whether the reaction cascade could be accomplished via direct α-enolization of esters 1, instead of indirect γ-enolization. When hydroxychalcone was coupled to vinylacetic acid, we observed complete olefin isomerization to give exclusively α,β-unsaturated product 1a.

Fortunately, when hydroxychalcone was coupled to various arylacetic acids, we were able is isolate esters 6 in good yields. (Fig. 4). These substrates tolerated α-enolization well and underwent the desired aldol elimination/6π-electrocyclization cascade at 120 oC to provide heterocycles 7a-7d in yields ranging from good to excellent. The reaction conditions were also suitable for the formation of phenanthradinones 7e and 7f. Unfortunately, phenyl- and pyridine- substituted 6g and 6h respectively did not undergo electrocyclization after triene formation, even when the reaction temperature was elevated to 180 oC.

Fig. 4.

Scope of electrocyclization cascade incorporating an aryl component; all reactions were performed by adding DBU (3.0 equiv) to a 0.15 M solution of 1 (1.0 equiv) in DMSO at room temperature. After stirring for 90 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was heated to 120 oC for 16 hours. aCompound was prone to intramolecular aldol elimination under coupling conditions and reaction was performed using the corresponding triene.

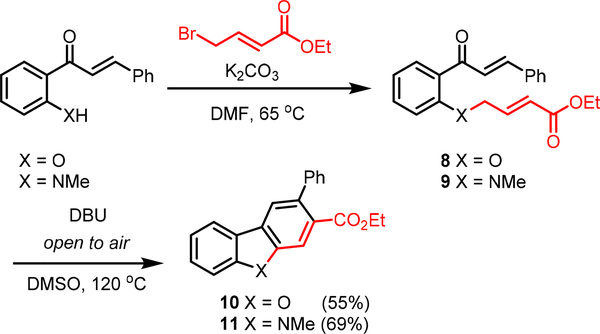

Lastly, we turned our attention towards accessing other benzannulated heterocyclic scaffolds, namely dibenzofurans and carbazoles (Fig. 5). By changing the chalcone coupling partner to ethyl 4-bromocrotonate, compounds 8 and 9 were prepared. We envision that when exposing to base, they could undergo enolization via γ-deprotonation, and unlike their 1 and 4 counterparts, act as nucleophiles from the γ-position as opposed to the α-position, setting the stage for the 6π-electrocyclization step. Indeed, when 8 and 9 were exposed to the optimized DBU heating conditions, 10 and 11 could be isolated in good yields. Notably, this reaction required heating to 120 oC, as evidence of incomplete electrocyclization was observed after heating to 80 oC for 16 hours.15

Fig. 5.

Aldol/electrocyclization route to carbazoles and dibenzofurans; all reactions were performed by adding DBU (3.0 equiv) to a 0.15 M solution of 1 (1.0 equiv) in DMSO at room temperature. After stirring for 90 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was heated to 120 oC for 16 hours.

In conclusion, we have disclosed a new method for the preparation of benzo[c]coumarin and phenanthradin-6(5H)-one scaffolds via a one-pot aldol elimination/6π-electrocyclization/oxidative aromatization reaction cascade. This new metal-free method benefits from high atom economy, straightforward starting material synthesis, and moderate to high yields. By altering the chalcone coupling partner, dibenzofurans and carbazoles can also be prepared in moderate yields using the method described herein. Application of this cascade to other scaffolds is currently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Susan Nimmo, Dr. Steven Foster, and Dr. Douglas R. Powell from the Research Support Services, University of Oklahoma, for expert NMR, mass spectral, and X-ray crystallographic analyses, respectively. The work was supported by the NSF CHE-1753187, and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (ACS-PRF) Doctoral New Investigator grant (PRF no. 58487-DNI1). Additional funding was provided by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institute of Health under grant number P20GM103640.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.(a) For reviews on cascade reactions, see: Ardkhean R, Caputo DFJ, Morrow SM, Shi H, Xiong Y and Anderson EA, Cascade Polycyclizations in Natural Product Synthesis, Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 1557–1569; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones AC; May JA, Sarpong R and Stoltz BM, Cascade Polycyclizations in Natural Product Synthesis, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 2556–2591; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicolaou KC and Chen JS, The Art of Total Synthesis through Cascade Reactions, Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 2993–3009; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vilotijevic I and Jamison TF, Epoxide-Opening Cascades in the Synthesis of Polycyclic Polyether Natural Products, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 5250–5281; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Padwa A, A Chemistry Cascade: From Physical Organic Studies of Alkoxy Radicals to Alkaloid Synthesis, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 6421–6441; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Padwa A, Chapter 2: Cascade Reactions of Carbonyl Ylides for Heterocyclic Synthesis, Prog. Heterocycl. Chem 2009, 20, 20–46; [Google Scholar]; (g) Ferreira VF, Synthesis of Heterocyclic Compounds by Carbenoid Transfer Reactions, Curr. Org. Chem 2007, 11, 177–193; [Google Scholar]; (h) Roos GHP and Raab CES, Dirhodium(II) Carbenes: A Rich Source of Chiral Products, Afr. J. Chem 2001, 54, 1–40; [Google Scholar]; (i) Padwa A, Tandem Processes of Metallo Carbenoids for the Synthesis of Azapolycycles, Top. Curr. Chem 1997, 189, 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trost BM, The Atom Economy—A Search for Synthetic Efficiency, Science 1991, 254, 1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolaou KC, Edmonds DJ and Bulger PG, Cascade Reactions in Total Synthesis, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7134–7186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 (a).Anastas PT and Warner JC, Green Chemistry; Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000; p 135; [Google Scholar]; (b) Matlack AS, Introduction to Green Chemistry; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2001; p 570. [Google Scholar]

- 5 (a).Chinthapally K, Massaro NP and Sharma I, Rhodium Carbenoid Initiated O-H Insertion/Aldol/Oxy-Cope Cascade for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Functionalized Oxacycles, Org. Lett, 2016, 18, 6340–6343; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chinthapally K, Massaro NP, Padgett HL and Sharma I, Serendipitous Cascade of Rhodium Vinylcarbenoids with Aminochalcones for the Synthesis of Functionalized Quinolines, Chem. Comm 2017, 53, 12205–12208; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Massaro NP, Stevens JC, Chatterji A and Sharma I, Stereoselective Synthesis of Diverse Lactones through a Cascade Reaction of Rhodium Carbenoids with Ketoacids, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 7585–7589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 (a).Cho BR, Kim YK, Seung YJ, Kim JC and Pyun SY, Elimination Reactions of Aryl Phenylacetates Promoted by R2NH/R2NH2+ in 70 mol MeCN(aq). Effect of the β-Phenyl Group on the Ketene-Forming Transition State, J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 1239–1242; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) You W, Li Y and Brown MK, Stereoselective Synthesis of All-Carbon Tetrasubstituted Alkenes from In Situ Generated Ketenes and Organometallic Reagents, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1610–1613; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pratt RF and Bruice TC, The Carbanion Mechanism (E1cB) of Ester Hydrolysis. III. Some Structure-Reactivity Studies and the Ketene Intermediate, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1970, 92, `5956–6964; [Google Scholar]; (d) Allen AD and Tidwell TT, Ketenes and Other Cumulenes as Reactive Intermediates, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 7287–7342; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Paull DH, Weatherwax A and Lectka T, Catalytic, Asymmetric Reactions of Ketenes and Ketene Enolates, Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6771–6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 (a).Okamura WH and De Lera AR, In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis; Trost BM, Fleming I and Paquette LA, Eds.; Pergamon Press: New York, 1991; Vol. 5, p 699; [Google Scholar]; (b) Essen RV, Frank D, Sunnemann HW, Vidovic D, Magull J and de Meijere A, Domino 6π-Electrocyclization/Diels-Alder Reactions on 1,6-Disubstituted (E,Z,E)-1,3,5-Hexatrienes: Versatile Access to Highly Substituted Tri- and Tetracyclic Systems, Chem. Eur. J 2005, 11, 6583–6592; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Voigt K, von Zezschwitz P, Rosauer K, Lanksy A, Adams A, Reiser O and de Meijere A, The Twofold Heck Reaction on 1,2-Dihalocycles and Subsequent 6π-Electroclyzation of the Resulting (E, Z, E,)-1,3,5-Hexatrienes: A New Formal [2+2+2]-Assembly of Six-Membered Rings, Eur. J. Org. Chem 1998, 1521–1534; [Google Scholar]; (d) von Zezschwitz P, Petry F and de Meijere A, A One-Pot Sequence of Stille and Heck Couplings: Synthesis of Various 1,3,5-Hexatrienes and their Subsequent 6π-Electrocyclizations, Chem. Eur. J 2001, 7, 4035–4046; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sunnemann HW and de Meijere A, Steroids and Steroid Analogues from Stille-Heck Coupling Sequences, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 895–897; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) von Essen R, von Zezschwitz P, Vidovic D, and de Meijere A, A New Phototransformation of Methoxycarbonyl-Substitutes (E, Z, E)-1,3,5-Hexatrienes: Easy Access to Ring-Annelated 8-Oxabicyclo[3.2.1]octa-2,6-diene Derivatives, Chem. Eur. J 2004, 10, 4341–4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 (a).Myers EL, and Trauner D (2012). 2.19 Selected Diastereoselective Reactions: Electrocyclizations Comprehensive Chirality. Carreira EM and Yamamoto H. Amsterdam, Elsevier: 563–606; [Google Scholar]; (b) Bian M, Li L and Ding H, Recent Advances on the Application of Electrocyclic Reactions in Complex Natural Product Synthesis, Synthesis, 2017, 49, 4383–4413; [Google Scholar]; (c) Choshi T and Hibino S, Synthetic Studies on Nitrogen-Containing Fused-Heterocyclic Compounds Based on Thermal Electrocyclic Reactions of 6π-Electron and Aza-6π Electron Systems, Heterocycles, 2011, 6, 1205–1240; [Google Scholar]; (d) Sunnemann HW, Banwell MG and de Meijere A, Synthesis and Use of New Substituted 1,3,5-Hexatrienes in Studying Thermally Induced 6π-Electrocyclizations, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2007, 3879–3893; [Google Scholar]; (e) Itoh T, Abe T, Choshi T, Nishiyama T, Yanada R and Ishikura M, Concise Total Synthesis of Pyrido[4,3-b]carbazole Alkaloids using Copper-Mediated 6π-Electrocyclization, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar]

- 9 (a).Mou C, Zhu T, Zheng P, Yang S, Song BA and Chi YR, Green and Rapid Access to Benzocoumarins via Direct Benzene Construction through Base-Mediated Formal [4+2] Reaction and Air Oxidation, Adv. Synth. Catal 2016, 358, 707–712; [Google Scholar]; (b) Poudel TN and Lee YR, An Advanced and Novel One-Pot Synthetic Method for Diverse Benzo[c]chromen-6-ones by Transition-Metal Free Mild Base-Promoted Domino Reaction of Substituted 2-HydroxyChalcones with β-Ketoesters and its Application to Polysubstituted Terphenyls, Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 919–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 (a).Turner CE, Elsohla MA and Boeren EGJ, Constituents of Cannabis Sativa L. XVII. A Review of the Natural Constituents, Nat. Prod 1980, 43, 169–234; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) ElSohly MA and Slade D, Chemical Constituents of Marijuana: The Complex Mixture of Natural Cannabinoids, Life Sci. 2005, 79, 539–548; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Raistrick H, Stickings CE and Thomas R, Studies in the Biochemistry of Micro-organisms: Alternariol and Alternariol Monomethyl Ether, Metabolic Products of Alternaria Tenuis, Biochemical Journal, 1953, 55, 421–433; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Li Y, Ding Y, Wang J, Su Y, and Wang X, Pd-Catalyzed C-H Lactonization for Expedient Synthesis of Biaryl Lactones and Total Synthesis of Cannabinol, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2574–2577; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sidwell WRL, Fritz H and Tamm Ch, Autumnariol and Autumnariniol, Two New Dibenzo-a-pyrons from Eucomis Autumnalis Graeb. Demonstration of a Remote Coupling Over Six Bonds in the Magnetic Proton Resonance Spectra, Helv. Chem. Act 1971, 54, 207–215; [Google Scholar]; (f) Nakamura M, Aoyama A, Salim MTA, Okamoto M, Baba M, Miyachi H, Hashimoto Y and Aoyama H, Structural Development Studies of Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Agents with a Phenanthradinone Skeleton, Bioorg. & Med. Chem 2010, 18, 2402–2411; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Patil S, Kamath S, Sanchez T, Neamati N, Schinazi RF and Buolamwini JK, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 5(H)-phenanthradin-6-ones, 5(H)-phenanthradin-6-one diketo Acid, and Polycyclic Aromatic Diketo Acid Analogues as New HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors, Bioorg. & Med. Chem 2007, 15, 1212–1228; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Manniche S, Sprogoe K, Dalsgaard PW, Christophersen C and Larsen TO, Karnatakafurans A and B: Two Dibenzofurans Isolated from the Fungus Aspergillus Karnatakaensis, J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 2111–2112; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Schmidt AW, Reddy KR and Knoller H, Occurrence, Biogenesis, and Synthesis of Biologically Active Carbazole Alkaloids, Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 3193–3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 (a).Bates R, Organic Synthesis Using Transition Metals, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012; p 462; [Google Scholar]; (b) Beller M and Bolm C, Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis, Vol. 1, 2nd ed; Wiley−VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KgaA, Weinheim: 2004; p 662; [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsuji J Transition Metal Reagents and Catalysts; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000; p 477. [Google Scholar]

- 12 (a).Schreiner PR, Metal-Free Organocatalysis through Explicit Hydrogen Bonding Interactions, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2003, 32, 289–296; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Su SD, Zhang J, Frank B, Thomas A, Wang X, Paraknowitsch J and Schlogl R, Metal-Free Heterogenous Catalysis for Sustainable Chemistry, ChemSusChem, 2010, 3, 169–180; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayler JD, Leahy DK, Simmons EM, A Pharmaceutical Industry Perspective on Sustainable Metal Catalysis, Organometallics, 2018, 38, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) For some examples of DBU mediated boc deprotection, see: Yang MC, Peng C, Huang H, Yang L, He XH, Huang W, Cui HL, He G and Han B, Organocatalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Spiro-oxindole Piperidine Derivatives that Reduce Cancel Cell Proliferation by Inhibiting MDM2-p53 Interaction, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 6752–6755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Millington EL, Dondas HA, Fishwick CWG, Kilner C and Grigg R, Catalytic bimetallic [Pd(0)/Ag(I) Heck-1,3-dipolar Cycloaddition Cascade Reactions Accessing Spiro-oxindoles. Concomitant In Situ Generation of Azomethine Ylides and Dipolarophile, Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3564–3577; [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Bringley DA, Zhang T and Cramer N, Rapid Access to Spirocyclic Oxindole Alkaloids: Application of the Asymmetric Palladium-Catalyzed [3+2] Trimethylenemethane Cycloaddition, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16720–16735; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Trost BM, Cramer N, and Bernsmann H, Concise Total Synthesis of (±)-Marcofortine B. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 3086–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 (a).Miao M, Jin M, Xu H, Chen P, Zhang S and Ren H, Synthesis of 5H-dibenzo[c,g]chromen-5-ones via FeCl3-Mediated Tandem C-O Bond Cleavage/6π Electrocyclization/Oxidative Aromatization, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 5718–5722; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moulton BE, Dong H, O’Brien CT, Duckett SB, Lin Z and Fairlamb IJS, A Natural Light Induced Regioselective 6π-Electrocyclization-Oxiative Aromatization Reaction: Experimental and Theoretical Insights, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2008, 6, 4523–4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha S, Banerjee A and Maji MS, Transition-Metal-Free Redox-Neutral One-Pot C3-Alkenylation of Indoles Using Aldehydes, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 6920–6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.