Abstract

The monkey frog, Pithecopus rusticus (Anura, Phyllomedusidae) is endemic to the grasslands of the Araucarias Plateau, southern Brazil. This species is known only from a small population found at the type locality. Here, we analyzed for the first time the chromosomal organization of the repetitive sequences, including seven microsatellite repeats and telomeric sequences (TTAGGG)n in the karyotype of the species by Fluorescence in situ Hybridization. The dinucleotide motifs had a pattern of distribution clearly distinct from those of the tri- and tetranucleotides. The dinucleotide motifs are abundant and widely distributed in the chromosomes, located primarily in the subterminal regions. The tri- and tetranucleotides, by contrast, tend to be clustered, with signals being observed together in the secondary constriction of the homologs of pair 9, which are associated with the nucleolus organizer region. As expected, the (TTAGGG)n probe was hybridized in all the telomeres, with hybridization signals being detected in the interstitial regions of some chromosome pairs. We demonstrated the variation in the abundance and distribution of the different microsatellite motifs and revealed their non-random distribution in the karyotype of P. rusticus. These data contribute to understand the role of repetitive sequences in the karyotype diversification and evolution of this taxon.

Keywords: Amphibia, Fluorescence in situ Hybridization, repetitive DNA

Introduction

The repetitive DNA sequences organized in tandem are abundant and widely distributed in the eukaryote genome (Charlesworth et al., 1994). The microsatellite repeats, or Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs), correspond to a class of repetitive DNA with less complex repetition units, composed of small, repeated in tandem motifs of one to six base pairs (Charlesworth et al., 1994; Vieira et al., 2016). These components of the genome are extremely useful as markers of genetic variation, due to hyper-polymorphism, and are used frequently in studies of population genetics. A number of mechanisms have been proposed to account for the high rates of variation found in the microsatellites, including the slippage of the DNA polymerase during replication and repair, the occurrence of unequal crossing-over, and ectopic recombination (Amos et al., 2015).

Contradicting the assumption that microsatellites correspond to essentially neutral sequences, a number of studies have demonstrated their considerable density in the eukaryote genome and their conservation in many different lineages, which suggest a functional role for some sequences. Microsatellite motifs have been identified as modulators of transcription factors and chromatin structure, enhancers, and RNA regulators, as well as being considered preferential sites for meiotic recombination enzymes (for a review, see Bagshaw, 2017). Other studies have found evidence of their involvement in chromosomal rearrangements (Kamali et al., 2011), and their tendency to accumulate in heteromorphic sex chromosomes indicates that they may participate in the differentiation and evolution of these chromosomes (Terencio et al., 2013; Pucci et al., 2016).

Microsatellite motifs are widely distributed in the genome, in both codifying and non-codifying regions, although some may have a non-random distribution, being organized in large genomic blocks, which can facilitate their detection in Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) experiments. The cluster organization pattern of these sequences in the karyotype may also favor recombination, either homologous or otherwise, which indicates the potential role of the sites as hotspots of chromosomal rearrangement, which is an important source of variation during karyotype diversification (Oliveira et al., 2006; Armour, 2006; Vieira et al., 2016).

A number of studies (Cuadrado and Jouve, 2007; Grandi and An, 2013; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015) have reported associations between microsatellites and different classes of repetitive sequence (histone gene spacers, rDNA, and mobile genetic elements), as well as being a component of the heterochromatic blocks in the karyotype. Furthermore, the mapping of microsatellite motifs in the karyotype can help distinguish chromosome pairs, provide a better characterization of the different classes of heterochromatin, and contribute to the identification of chromosomal rearrangements, which means that they provide an extremely informative marker for the differentiation of karyotypes (Farré et al., 2011; Paço et al., 2013; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2016). However, few studies have adopted this approach up to now, in particular in amphibians (Peixoto et al., 2015; 2016).

The monkey frog, Pithecopus rusticus, is an amphibian species endemic to the grasslands of the Araucaria Plateau, in the Atlantic Forest domain of southern Brazil (Bruschi et al., 2014a). This species is currently known only from a small population found at the type locality, in the municipality of Água Doce, in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil (Lucas et al., 2010; Bruschi et al., 2014a). The genus Pithecopus (Cope, 1866; recently resurrected from the genus Phyllomedusa by Duellman et al., 2016) has 11 recognized species (Frost, 2019), all of which have highly conserved karyotypes, in terms of both the diploid number (2n=26) and chromosome morphology (Barth et al., 2009; Bruschi et al., 2012; Bruschi et al., 2014b). The closest phylogenetically related species to P. rusticus are P. ayeaye, P. megacephalus, P. centralis, and P. oreades (Bruschi et al., 2014a), which are all found on the plateaus and highland areas of the Cerrado savannas of central Brazil (Faivovich et al., 2010; Bruschi et al., 2014a).

Cytogenetic data on P. rusticus will be fundamental to a better understanding of the origin and diversification of this taxon, given its restricted geographic distribution, which is completely disjunct from those of other species of the genus. In this study, we present the genomic organization of seven microsatellite motifs and the (TTAGGG)n repeats in the karyotype of P. rusticus, and we demonstrate the non-random distribution of these repeats, in association with the 45S rDNA gene.

Material and Methods

Biological samples

Tissue samples were obtained from 6 males specimens of Pithecopus rusticus paratypes collected during the fieldwork, between 2009 and 2012, that led to the original description of the species (Lucas et al., 2010; Bruschi et al., 2014a). Vouchers are deposited in Coleção de Anfíbios da Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó (UNOCHAPECÓ), Santa Catarina States, Brazil under numbers CAUC0763, CAUC13356, CAUC0766, CAUC0768, CAUC0770 and CAUC0771. These specimens were collected at the type locality, in the municipality of Água Doce, in the state of Santa Catarina, in southern Brazil (26º35’59.90” S, 51º34’39.40” W). The cell suspensions were prepared from intestinal and testicular tissue (Bruschi et al., 2014a), which had been treated with 2% colchicine, using procedures modified from King and Rofe (1976) and Schmid (1978). The cell suspensions were dripped onto clean microscope slides and stored at -20°C. The nucleolar organizer regions (NOR) were revealed by Ag-NOR technique (Howell and Black, 1980) and cofirmed by in situ hybridization with 28S rDNA probes, isolated, cloned and sequenced according to Bruschi et al. (2012) from Pithecopus hypochondrialis.

Probes of the microsatellite repeats and telomeric (TTAGGG)n sequences

The microsatellites were analyzed using oligonucleotide probes – CA(15), GA(15), GAA(10), CAG(10), CGC(10), GACA(4), GATA(8) – marked directly with Cy5 fluorochrome (Sigma Aldrich) at the 5’ end during the synthesis of the DNA. The telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeats were produced by PCR amplification using telomeric primers F (5’ TTAGGG 3’) and R (5’ CCCTAA 3’), with the product of this amplification being marked directly by the incorporation of 11-digoxigenin-dUTP, following the protocol described by Guerra (2012).

Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) experiments

The microsatellite FISH experiments were based on the protocol propose by Kubat et al. (2008). For telomeric repeats, the hybridizations were conducted according to the protocol of Traut et al. (2001), with the following modifications: the slides were washed in 0.2N HCl for 2 minutes, followed by two washes in PBST for 3 minutes, with the chromatin structure being stabilized in 1%/150 mM PBS 1X formaldehyde, for 10 minutes, then washed again in PBST for 3 minutes, and dehydrated in an increasing alcohol series (at 70%, 80%, and 96%) for 3 minutes. The samples were denatured in deionized 70%/2xSSC formamide for 3 minutes at 70°C and then dehydrated again in an increasing alcohol series (at 70%, 80%, and 96%).

For hybridization, each slide received a final concentration of 50ng/uL of the probe. After 24 hours of hybridization in a wet chamber at 37°C, the slides were washed in 2X SSC at 42°C and in PBST for 5 minutes, and then dehydrated again in an increasing alcohol series (at 70%, 80%, and 96%) for 3 minutes. The slides were then incubated in NFDM buffer for 15 minutes, and the signal was detected using the antidigoxigenin antibody in NFDM buffer for 1 hour in a wet and dark chamber, at room temperature. The slides were then washed again, three times, in 0.5%/4xSSC Tween for 5 minutes, dehydrated in the alcohol series, and counterstained with DAPI. Ten metaphases per individual were photographed under Olympus BX-51 epifluorescence microscope.

Results

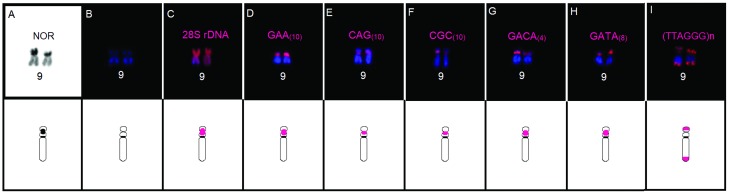

The diploid number in all specimens analyzed showed 26 chromosomes. The dinucleotide microsatellite probes CA(15) (Figure 1A) and GA(15) (Figure 1B) were distributed abundantly in all the chromosomes and presented signals of hybridization in the subterminal regions. Interstitial CA(15) hybridizations were also observed in the long arms of the homologs of pairs 4 and 5, and in the pericentromeric regions of the short arms of pair 5 and the long arms of pairs 11 and 12 (Figure 1A). Interstitial hybridizations of the GA(15) were detected in the long arm of the homologs of pair 3 (Figure 1B).

The trinucleotide – GAA(10), CAG(10), CGC(10) (Figure 1C-E) – and tetranucleotide – GACA(4) and GATA(8) (Figure 1F-G) – microsatellites presented clustered hybridization signals in the secondary constrictions of the homologs of pair 9, involving the secondary constriction related to the NOR site described (Bruschi et al., 2014a; present study – Figure 2A-C). Considerable variation in signal strength was also observed for each marker, with GAA(10), GACA(4) and GATA(8) presenting stronger signals (Figure 2). Interstitial signals of GAA(10) (Figure 1C) were also detected on the short arms of pair 2 and in one of the homologs of pair 4.

The in situ hybridization detected (TTAGGG)n sequences in all the chromosomes of the P. rusticus karyotype (Figure 1H). Hybridization signals were also detected in the pericentromeric region of pairs 5 and 8. Intense hybridization signals of (TTAGGG)n sequences were detected in the homologs of pair 13 (Figure 1H) .

Figure 1. Metaphase chromosomes of Pithecopus rusticus (2n=26) submitted to Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) with the microsatellite for the repeats of (A) CA(15); (B) GA(15); (C) GAA(10); (D) CAG(10); (E) CGC(10); (F) GACA(4); (G) GATA(8), and (H) the telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeats. The partial karyotypes are presented in (B) and (E). The arrows indicate the interstitial and pericentromeric signals. In (B) and (E), the chromosome pairs with GA(15) and CGC(10) signals (respectively) are shown in the boxes.

Figure 2. Homologs of chromosome pair 9 in Pithecopus rusticus and diagrams of the co-location of the hybridization signals highlighted in (A) the Nucleolus Organizer Region (Ag-NOR); (B) secondary constrictions (DAPI); (C) the 28S rDNA; (D–H) distribution patterns of different microsatellite markers; (I) telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeats.

Discussion

The in situ mapping of the different microsatellite repeats contributed to the understanding of the chromosomal organization of this repetitive DNA in the karyotype of Pithecopus rusticus. The results of the present study indicated that the dinucleotide motifs has a chromosomal distribution pattern distinct from those of tri- and tetranucleotides. The CA(15) and GA(15) microsatellites are abundant and widely distributed in the chromosomes, and are located primarily in the subterminal regions of the chromosomes.

Repeats of (CA)n and (GA)n appear to be the most common microsatellite dinucleotide motifs in animal genomes (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015) and have been linked to the high rates of recombination observed in these organisms (Guo et al., 2009), due to their affinity with the recombination enzymes (Biet et al., 1999). The distribution of these motifs, especially in the subterminal region, may also be important for the stabilization of the chromosomes terminal portions. A similar accumulation of dinucleotide repetitions in the chromosomes subterminal regions has been observed in some species of amphibians of the genus Ololygon (Peixoto et al., 2015, 2016), in several species of fish (Poltronieri et al., 2013; Schneider et al., 2015; Pucci et al., 2016), grasshoppers (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015), and plants (Vanzela et al., 2002; Torres et al., 2011). The arrangement of repetitive DNA in the subtelomeric region appears to be a common characteristic of the eukaryotic chromosome, driven by different mechanisms of enrichment (transposable elements, satellites and microsatellites), which have played a fundamental role in the formation of the heterochromatin in these regions (Torres et al., 2011). In a study of fission yeasts, Tashiro et al. (2017) confirmed the importance of this type of subterminal region organization for telomere function, regulation of adjacent genes and chromosome homeostasis.

By contrast, the tri- and tetranucleotide motifs mapped here presented a clustered distribution in the same chromosomal region, as observed in the pericentromeric region, extending to the interstitial portion of the homologs of pair 9. The patterns of genomic organization (dispersed or clustered) of repetitive sequences likely reflect distinct evolutionary events (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015; Utsunomia et al., 2018) and the potential of each motif for expansion (Pokorná et al., 2011; Kejnovský et al., 2013). Several studies have shown that the accumulation of microsatellites in the eukaryotic genomes is not random, and closely-related species tend to present a tendency for accumulation of repetitions in a specific chromosome (Cuadrado and Jouve, 2007; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2016; Utsunomia et al., 2018), which may reflect an important functional role (Cuadrado and Jouve, 2007; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015).

Pithecopus rusticus has a single NOR site located in the subterminal region of chromosomal pair 9 (Bruschi et al., 2014a; presente study), in which hybridization signals were detected of both trinucleotide [GAA(10), CAG(10), CGC(10)] and tetranucleotide [GACA(4) and GATA(8)] repeats. For example, the distribution of the (GAA)n sequence was related to chromosomal rearrangements/modifications involving primarily NOR-bearing chromosomes, as observed in a number of different lineages of wheat, Triticum spp. (Adonina et al., 2015). The frequent association between microsatellite repeats and the NORs is not entirely unexpected, given that the massive presence of microsatellite repeats has been observed in intergenic spacers (IGSs) in the rDNA (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015; Agrawal and Ganley, 2018). The association between microsatellite repeats and IGS regions, in particular di- and trinucleotide motifs has been confirmed by analysis of reads combined with FISH experiments in grasshoppers (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015) and also corroborated in the present study.

While the centromere is formed primarily of repetitive DNA, none of the microsatellite repeats were detected in this region in P. rusticus, which may be related to the fact that the centromeres reduce recombination rates and, as a consequence the amplification of these microsatellite motifs in this region (Guo et al., 2009). Therefore, the microsatellite sequences are normally found in the regions adjacent to the centromere, as observed in the pericentromeric signals of the CA(15) repeats in some of the P. rusticus chromosomes.

As expected, the (TTAGGG)n probes hybridized in all terminal regions of the chromosomes, since this sequence is highly conserved in all vertebrates (Bolzán, 2017). In addition to these signals, our FISH experiments revealed large blocks of (TTAGGG)n repeats distributed in the internal regions of the chromosomes, that is, Interstitial Telomeric Sequences (ITSs). The mapping of ITSs seems to be useful for the detection of interchromosomal rearrangements, such as fusions, or intrachromosomal rearrangements of the inversion type (Teixeira et al., 2016; Bolzán, 2017). However, the ITSs are also capable of spreading rapidly, as observed in the pericentromeric regions, probably independently (Wiley et al., 1992; Rovatsos et al., 2011; Bruschi et al., 2014b).

The detection of ITSs in P. rusticus, in addition to the presence of interstitial signals in the karyotypes of the other species of the family Phyllomedusidae analyzed to date (Gruber et al., 2013; Barth et al., 2014; Bruschi et al., 2014b), indicates that the presence of this type of sequence is recurrent in these frogs. The intrachromosomal variation in the telomeric repeats found in different Phyllomedusa species (e.g., Phyllomedusa vaillantii, Phyllomedusa tarsius, Phyllomedusa distincta, and Phyllomedusa bahiana) reflects different patterns of (TTAGGG)n signals in the interstitial regions of the chromosomes of these species (Bruschi et al., 2014b). However, the clear conservation of the chromosome structure in this group, the origin of the ITSs detected in the present study probably cannot be explained by rearrangements, but may be a result of the amplification of (TTAGGG)n repeats, which occurred independently during the chromosomal evolution of these species. Interestingly, these ITSs are associated with heterochromatin, given that they were detected in pericentromeric regions, coinciding with the C-band positive blocks reported by Bruschi et al. (2014a), and a similar pattern has been observed in the Phyllomedusa species (Bruschi et al., 2014b), and in other anuran species (Schmid and Steinlein, 2016). As observed in P. rusticus, intense hybridization signals were also detected in the homologs of pair 13 in Phyllomedusa vaillantii, indicating that the (TTAGGG)n sequence is an important component of the repetitive DNA of these chromosomes in the phyllomedusids (Bruschi et al., 2014b).

A few studies have investigated the cytogenetic characteristics of the phyllomedusids, including descriptions of karyotypes, the identification of heterochromatic regions and NOR sites (Morand and Hernando, 1997; Barth et al., 2009, 2013, 2014; Paiva et al., 2010; Bruschi et al., 2012, 2013, 2014a, 2014b; Gruber et al., 2013). Pithecopus rusticus is apparently limited to a small and isolated population, the evaluation of the composition and distribution of repetitive DNA in the genome is fundamental to understand the role of these sequences in the evolution of the karyotype of this taxon. DNA sequences that are widely repeated in the genome are capable of evolving independently and also serve as a substrate for recombinations and chromosomal rearrangements (Kamali et al., 2011; Carmona et al., 2013; Utsunomia et al., 2018) and in small and interbreeding populations, such as P. rusticus, evolutionary novelties may arise frequently and will be fixed rapidly in the population (Gemayel et al., 2010). Therefore, the results of the present study provide important insights into the diversification and distribution of repetitive sequences in the P. rusticus karyotype, which may be useful, in particular, for comparative analyses, and the understanding of evolutionary mechanisms that determine the characteristics of this taxon, in addition to the molecular cytogenetics of amphibians, in general.

Acknowledgments

JRE would like to thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior Brasil (CAPES) for the postgraduate scholarship. We thank the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP; Process 2016/07717-6). We are greatful to Centro de Tecnologias Avançadas em Fluorescência (CETAF/UFPR) for the support during the research.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Yatiyo Yonenaga-Yassuda

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

JRE conduced the experiments, analyzes the data and wrote the manuscript; CBG assisted in the execution and analysis of FISH experiments; EML and SMRP helped draft the manuscript; DPB designed and coordinated the study, wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

References

- Adonina IG, Goncharov NP, Badaeva ED, Sergeeva EM, Petrash N V., Salina EA. (GAA)n microsatellite as an indicator of the A genome reorganization during wheat evolution and domestication. Comp Cytogenet. 2015;9:533–547. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i4.5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S, Ganley ARD. The conservation landscape of the human ribosomal RNA gene repeats. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos W, Kosanovic D, Eriksson A. Inter-allelic interactions play a major role in microsatellite evolution. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2015;282:20152125. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour JAL. Tandemly repeated DNA: Why should anyone care? Mutat Res - Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 2006;598:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw ATM. Functional mechanisms of microsatellite DNA in eukaryotic genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:2428–2443. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A, Solé M, Costa MA. Chromosome Polymorphism in Phyllomedusa rohdei Populations (Anura: Hylidae) J Herpetol. 2009;43:676–679. [Google Scholar]

- Barth A, Souza VA, Solé M, Costa MA. Molecular cytogenetics of nucleolar organizer regions in Phyllomedusa and Phasmahyla species (Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae): A cytotaxonomic contribution. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:2400–2408. doi: 10.4238/2013.July.15.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A, Vences M, Solé M, Costa MA. Molecular cytogenetics and phylogenetic analysis of Brazilian leaf frog species of the genera Phyllomedusa and Phasmahyla (Hylidae: Phyllomedusinae) Can J Zool. 2014;92:795–802. [Google Scholar]

- Biet E, Sun JS, Dutreix M. Conserved sequence preference in DNA binding among recombination proteins: An effect of ssDNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:596–600. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolzán AD. Interstitial telomeric sequences in vertebrate chromosomes: Origin, function, instability and evolution. Mutat Res - Rev Mutat Res. 2017;773:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi DP, Busin CS, Siqueira S, Recco-Pimentel SM. Cytogenetic analysis of two species in the Phyllomedusa hypochondrialis group (Anura, Hylidae) Hereditas. 2012;149:34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2010.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi DP, Busin CS, Toledo LF, Vasconcellos GA, Strussmann C, Weber LN, Lima AP, Lima JD, Recco-Pimentel SM. Evaluation of the taxonomic status of populations assigned to Phyllomedusa hypochondrialis (Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae) based on molecular, chromosomal, and morphological approach. BMC Genet. 2013;14:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi DP, Lucas EM, Garcia PCA, Recco-Pimentel SM. Molecular and morphological evidence reveals a new species in the Phyllomedusa hypochondrialis group (Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae) from the Atlantic Forest of the highlands of Southern Brazil. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi DP, Rivera M, Lima AP, Zúñiga AB, Recco-Pimentel SM. Interstitial Telomeric Sequences (ITS) and major rDNA mapping reveal insights into the karyotypical evolution of Neotropical leaf frogs species (Phyllomedusa, Hylidae, Anura) Mol Cytogenet. 2014;7:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona A, Friero E, de Bustos A, Jouve N, Cuadrado A. Cytogenetic diversity of SSR motifs within and between Hordeum species carrying the H genome: H. vulgare L. and H. bulbosum L. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:949–961. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-2028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Sniegowski P, Stephan W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;371:215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope ED. On the structures and distribution of the genera of the arciferous Anura. J Acad Nat Sci Philadelphia Ser. 1866;2, 6:67–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Jouve N. The nonrandom distribution of long clusters of all possible classes of trinucleotide repeats in barley chromosomes. Chromosom Res. 2007;15:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duellman WE, Marion AB, Hedges SB. Phylogenetics, classification, and biogeography of the treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae) Zootaxa. 2016;4104:1–109. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4104.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivovich J, Haddad CFB, Baêta D, Jungfer KH, Álvares GFR, Brandão RA, Sheil C, Barrientos LS, Barrio-Amorós CL, Cruz CAG, et al. The phylogenetic relationships of the charismatic poster frogs, Phyllomedusinae (Anura, Hylidae) Cladistics. 2010;26:227–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré M, Bosch M, López-Giráldez F, Ponsà M, Ruiz-Herrera A. Assessing the role of tandem repeats in shaping the genomic architecture of great apes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemayel R, Vinces MD, Legendre M, Verstrepen KJ. Variable tandem repeats accelerate evolution of coding and regulatory sequences. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:445–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-072610-155046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi FC, An W. Non-LTR retrotransposons and microsatellites. Mob Genet Elements. 2013;3:e25674. doi: 10.4161/mge.25674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber SL, Silva APZ, Haddad CFB, Kasahara S. Cytogenetic analysis of Phyllomedusa distincta Lutz, 1950 (2n = 2x = 26), P. tetraploidea Pombal and Haddad, 1992 (2n = 4x = 52), and their natural triploid hybrids (2n = 3x = 39) (Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae) BMC Genet. 2013;14:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra M. Citogenetica Molecular: Protocolos Comentados. 1st edition. Sociedade Brasileira de Genética; Ribeirão Preto: 2012. p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Ling J, Li P. Consensus features of microsatellite distribution: Microsatellite contents are universally correlated with recombination rates and are preferentially depressed by centromeres in multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Genomics. 2009;93:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell WM, Black DA. Controlled silver staining of nucleolar organizer regions with a protective colloidal developer: A 1 step method. Experientia. 1980;36:1014–1015. doi: 10.1007/BF01953855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali M, Sharakhova M V., Baricheva E, Karagodin D, Tu Z, Sharakhov I V. An integrated chromosome map of microsatellite markers and inversion breakpoints for an Asian malaria mosquito, Anopheles stephensi. J Hered. 2011;102:719–726. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esr072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kejnovský E, Michalovova M, Steflova P, Kejnovska I, Manzano S, Hobza R, Kubat Z, Kovarik J, Jamilena M, Vyskot B. Evolution of microsatellites on evolutionary young Y chromosome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e45519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Rofe R. Karyotypic variation in the Australian Gekko Phyllodactylus marmoratus (Gray) (Gekkonidae: Reptilia) Chromosoma. 1976;54:75–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00331835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubat Z, Hobza R, Vyskot B, Kejnovsky E. Microsatellite accumulation on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia . Genome. 2008;51:350–356. doi: 10.1139/G08-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas EM, Fortes VB, Garcia PCA. Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusa azurea Cope, 1862: Distribution extension to southern Brazil. Check List. 2010;6:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Morand M, Hernando AB. Localización cromosómica de genes ribosomales activos en Phyllomedusa hypochondrialis y P. sauvagii . Cuad Herpetol. 1997;11:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira EJ, Pádua JG, Zucchi MI, Vencovsky R, Vieira MLC. Origin, evolution and genome distribution of microsatellites. Genet Mol Biol. 2006;29:294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Paço A, Chaves R, Vieira-da-Silva A, Adega F. The involvement of repetitive sequences in the remodelling of karyotypes: The Phodopus genomes (Rodentia, Cricetidae) Micron. 2013;46:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva CR, Nascimento J, Silva APZ, Bernarde PS, Ananias F. Karyotypes and Ag-NORs in Phyllomedusa camba De La Riva, 1999 and P. rhodei Mertens, 1926 (Anura, Hylidae, Phyllomedusinae): Cytotaxonomic considerations. Ital J Zool. 2010;77:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto MAA, Lacerda JVA, Coelho-Augusto C, Feio RN, Dergam JA. The karyotypes of five species of the Scinax perpusillus group (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae) of southeastern Brazil show high levels of chromosomal stabilization in this taxon. Genetica. 2015;143:729–739. doi: 10.1007/s10709-015-9870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto MAA, Oliveira MPC, Feio RN, Dergam JA. Karyological study of Ololygon tripui (Lourenço, Nascimento and Pires, 2009), (Anura, Hylidae) with comments on chromosomal traits among populations. CCG. 2016;10:505–516. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i4.9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorná M, Kratochvíl L, Kejnovský E. Microsatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and heterochromatinization in two lizard species (Squamata: Eublepharidae: Coleonyx elegans and Lacertidae: Eremias velox) BMC Genet. 2011;12:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltronieri J, Marquioni V, Bertollo LAC, Kejnovsky E, Molina WF, Liehr T, Cioffi MB. Comparative chromosomal mapping of microsatellites in Leporinus species (characiformes, anostomidae): Unequal accumulation on the W chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2013;142:40–45. doi: 10.1159/000355908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucci MB, Barbosa P, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Scacchetti PC, Pansonato-Alves JC, Foresti F, Moreira-Filho O, Vicari MR. Chromosomal Spreading of Microsatellites and (TTAGGG)n Sequences in the Characidium zebra and C. gomesi Genomes (Characiformes: Crenuchidae) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;149:182–190. doi: 10.1159/000447959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovatsos MT, Marchal JA, Romero-Fernández I, Fernández FJ, Giagia-Athanosopoulou EB, Sánchez A. Rapid, independent, and extensive amplification of telomeric repeats in pericentromeric regions in karyotypes of arvicoline rodents. Chromosom Res. 2011;19:869–882. doi: 10.1007/s10577-011-9242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ruano FJ, Cuadrado Á, Montiel EE, Camacho JPM, López-León MD. Next generation sequencing and FISH reveal uneven and nonrandom microsatellite distribution in two grasshopper genomes. Chromosoma. 2015;124:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00412-014-0492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ruano FJ, López-León MD, Cabrero J, Camacho JPM. High-throughput analysis of the satellitome illuminates satellite DNA evolution. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28333. doi: 10.1038/srep28333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M. Chromosome banding in Amphibia - I. Constitutive heterochromatin and nucleolus organizer regions in Bufo and Hyla . Chromosoma. 1978;66:361–388. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Steinlein C. Chromosome banding in Amphibia. XXXIV. Intrachromosomal telomeric DNA sequences in Anura. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;148:211–226. doi: 10.1159/000446298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CH, Gross MC, Terencio ML, de Tavares ÉSGM, Martins C, Feldberg E. Chromosomal distribution of microsatellite repeats in Amazon cichlids genome (Pisces, Cichlidae) Comp Cytogenet. 2015;9:595–605. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i4.5582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro T, Nishihara Y, Kugou K, Ohta K, Kanoh J. Subtelomeres constitute a safeguard for gene expression and chromosome homeostasis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:10333–10349. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira LSR, Seger KR, Targueta CP, Orrico VGD, Lourenço LB. Comparative cytogenetics of tree frogs of the Dendropsophus marmoratus (Laurenti, 1768) group: Conserved karyotypes and interstitial telomeric sequences. Comp Cytogenet. 2016;10:753–767. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i4.9972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terencio ML, Schneider CH, Gross MC, Vicari MR, Farias IP, Passos KB, Feldberg E. Evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in Semaprochilodus (characiformes, prochilodontidae): A fish model for sex chromosome differentiation. Sex Dev. 2013;7:325–333. doi: 10.1159/000356691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GA, Novák P, Bryan GJ, Hirsch CD, Gong Z, Buell CR, Iovene M, Macas J, Jiang J. Organization and evolution of subtelomeric satellite repeats in the potato genome. G3. 2011;1:85–82. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut W, Eickhoff U, Schorch JC. Identification and analysis of sex chromosomes by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) Methods Cell Sci. 2001;23:155–161. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-0330-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsunomia R, Melo S, Scacchetti PC, Oliveira C, Machado M de A, Pieczarka JC, Nagamachi CY, Foresti F. Particular chromosomal distribution of microsatellites in five species of the genus Gymnotus (Teleostei, Gymnotiformes) Zebrafish. 2018;15:398–403. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2018.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzela ALL, Swarça AC, Dias AL, Stolf R, Ruas PM, Ruas CF, Sbalqueiro IJ, Giuliano-Caetano L. Differential distribution of (GA)+C microsatellite on chromosomes of some animal and plant species. Cytologia. 2002;67:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira MLC, Santini L, Diniz AL, Munhoz C de F. Microsatellite markers: What they mean and why they are so useful. Genet Mol Biol. 2016;39:312–328. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JE, Meyne J, Little ML, Stout JC. Interstitial hybridization sites of the (TTAGGG)n telomeric sequence on the chromosomes of some North American hylid frogs. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1992;61:55–57. doi: 10.1159/000133368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Sun C, Zhang S, Hou X, Bonnema G. Cytogenetic Diversity of Simple Sequences Repeats in Morphotypes of Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis . Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1049. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet resources

- Frost DR. Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. 2019. [accessed April 05, 2019]. http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html.