Abstract

The increasing threat of antimicrobial resistance has shed light on the interconnection between humans, animals, the environment, and their roles in the exchange and spreading of resistance genes. In this review, we present evidences that show that Staphylococcus species, usually referred to as harmless or opportunistic pathogens, represent a threat to human and animal health for acting as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes. The capacity of genetic exchange between isolates of different sources and species of the Staphylococcus genus is discussed with emphasis on mobile genetic elements, the contribution of biofilm formation, and evidences obtained either experimentally or through genome analyses. We also discuss the involvement of CRISPR-Cas systems in the limitation of horizontal gene transfer and its suitability as a molecular clock to describe the history of genetic exchange between staphylococci.

Keywords: Horizontal gene transfer, antimicrobial resistance, coagulase negative staphylococcus, biofilm, CRISPR, One Health

Introduction

Every year, hundreds of thousands of deaths around the world are attributed to the ever increasing problem of antimicrobial resistance (Laxminarayan et al., 2016). It is estimated that, if the issue is not properly addressed, by the year of 2050, more than 10 million annual deaths will be caused by antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms, surpassing deaths by cancer (O’Neill, 2014). Although the accuracy of this frightening estimate is questioned by some authors, since the future scenario of disease treatment may be considerably different from the current one, the clinical, economical, and public health burden associated with antimicrobial resistance is undeniable (Kraker et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2016).

In the context of resistance dissemination, bacteria of the Staphylococcus genus, residents of the normal microbiota of human beings and animals, play a central role. Staphylococcus aureus is the main pathogen of the group, responsible for a variety of clinical infections in humans and a leading cause of bacteremia, endocarditis, and many infections related to invasive medical devices (Tong et al., 2015). Meanwhile, coagulase negative staphylococci (CoNS), especially S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus, have emerged as recurrent causative agents of nosocomial infections, mainly those related to indwelling devices (Becker et al., 2014). They are a serious threat in the twilight of the multidrug resistance era, for actively participating in the horizontal transmission of resistance (Becker et al., 2014; Czekaj et al., 2015).

Genomic analyses indicate that many of the genetic determinants of resistance may have been exchanged between several staphylococcal species from different environments and hosts (Rolo et al., 2017; Rossi et al., 2017a; Kohler et al., 2018;). This includes species that are understudied and/or underestimated, either for having been recently discovered, rarely involved with infectious diseases, or for lacking canonical staphylococcal virulence factors. However, recent evidence shows that these underrated species, despite not being usual pathogens, may have an important role in the exchange of antimicrobial resistance genes, by acting as gene-reservoirs for more pathogenic species, such as S. aureus (Otto, 2013; Rossi et al., 2017a, 2019).

Given the increasing recognition of the importance of previously overlooked Staphylococcus species, the goal of this review was to present evidences that put these bacteria in the front row of resistance dissemination and highlight their potential threat to human and animal health.

Antimicrobial resistance increase and the interconnectedness of its spreading

In the past decade, consumption of antibiotic drugs increased by 35%, with 76% of this growth concentrated in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (Van Boeckel et al., 2014), with a projection of a rise in consumption in the next 15 years of 67% (Van Boeckel et al., 2015). The disturbing situation of antimicrobial resistance led the World Health Organization to elaborate the “Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance”, with goals that include: (i) improving the understanding of the problem through communication, education and training, (ii) increasing surveillance and research, (iii) advancing in preventive actions to reduce the incidence of infections, and (iv) optimizing the use of antimicrobial drugs in human and veterinary health (WHO, 2017). Tied to this worldwide concern to restrain the dispersion of resistance, the emerging engagement of scientists and other professionals with the “One Health” agenda increases the acknowledgement of the need for global approaches as the only possible way to keep the predicted disaster of 2050 of more than 10 million annual deaths caused by resistant microorganisms from actually happening.

Considered as a “new professional imperative”, One Health is a collaborative and multidisciplinary effort to achieve optimal health for people, animals and our environment from local to global scales (King et al., 2008). It recognizes that the welfare of these three domains is interconnected and this link, ignored for so long, is crucial for the spreading of antimicrobial resistance. The use of antimicrobial drugs in agriculture, for example, is the largest worldwide, thus being a major driver of resistance for several reasons, like exposure of bacteria to sub-therapeutic doses of the antibiotics and the exposure of human and animals to those drugs and microorganisms, either via consumption of products or environmental release (Silbergeld et al., 2008). Studies also point out that the use of antimicrobial drugs, particularly to maintain health, productivity, and promoting growth of food animals, contribute to the dispersion of resistant bacteria in livestock and human beings (Marshall and Levy, 2011; Van Boeckel et al., 2015). In aquaculture, it is estimated that around 80% of antimicrobials used reach the environment with their activity intact, thereby expanding the surroundings where selection of resistant microorganisms will take place (Cabello et al., 2013). Even insects commonly associated with food animals, like houseflies and cockroaches, are presumably vehicles of microorganisms from the farms to urban centers (and vice versa), as evidenced by multidrug-resistant clonal lineages carried by them, that were also isolated from different environments (Zurek and Ghosh, 2014).

Pet animals have been shown to act as reservoirs of resistant bacteria, which in turn act as reservoirs of mobile genetic elements that carry antimicrobial resistance genes (Guardabassi et al., 2004; Rossi et al., 2017a). In fact, the relationship between the animals and their owners significantly shapes the microbiota of both counterparts (Song et al., 2013). For that reason, the indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in veterinary practice represents a direct threat to human beings. More aggravating is the fact that some drugs that are either not recommended to be used in humans, or those that are considered as last resources, are heavily used to treat animals. Some examples include the polymixins and chloramphenicol and its derivatives, the latter presenting several adverse effects that limit its employment (Cabello et al., 2013; Poirel et al., 2017).

Consistently, multidrug resistant strains, like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are ubiquitous, being isolated from humans, pets, food, other animals and the environment (Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010; Kock et al., 2013; Rossi et al., 2017b). Due to local variations in control practices and specific characteristics of circulating clones, the overall geographic distribution of MRSA, for example, can range from 1 to 5% of isolates in northeastern Europe to more than 50% in certain Latin American countries (Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile) and in Japan (Lee et al., 2018).

Variety and clinical significance of Staphylococcus spp.

Although S. aureus is the major bacterium of its genus, more than 50 Staphylococcus species are registered in the List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature database, available at http://www.bacterio.net (Parte, 2018). However, DNA sequencing of complete genomes or housekeeping genes, phylogenetic analyses, DNA–DNA hybridization, protein profiles, and genotyping techniques have constantly led to reclassifications or proposals of new species and subspecies (Sasaki et al., 2007; Fitzgerald, 2009; Taponen et al., 2012). As these techniques advance and new sources of Staphylococcus are explored, especially in different animals, new species are also discovered, such as S. nepalensis, isolated from goats (Spergser et al., 2003), S. stepanovicii, isolated from wild small animals (Hauschild et al., 2010), S. pseudintermedius, isolated from several domestic animals, such as dogs, cats, horses and parrots (Devriese et al., 2005), and S. agnetis, isolated from bovines with subclinical and clinical mastitis (Taponen et al., 2012).

In general, staphylococci are natural inhabitants of skin and mucous membranes of human beings and animals, while the prevalence of species widely varies according to the host. S. felis, for example, is typically isolated from feline, either healthy or presenting signs of lower urinary tract disease, otitis externa, and ocular disease (Rossi et al., 2017b; Worthing et al., 2018); S. pseudintermedius is prevalent in domestic dogs, healthy or related to diseases like pyoderma and otitis externa (Ruscher et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2018); S. caprae is involved with intramammary infections in dairy goats (Moroni et al., 2005), among others. Regardless of their source, infections caused by unusual human pathogens are sporadically reported (Morfin-Otero et al., 2012; Novakova et al., 2006a,b), with special emphasis on those caused by S. pseudintermedius, with most cases indicating the contact of domestic dogs with their owners as the probable source of infection (Van Hoovels et al., 2006; Riegel et al., 2011; Lozano et al., 2017). Given their great adaptability to unfavorable conditions (Uribe-Alvarez et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2017c), staphylococci isolated from the surrounding environment are also responsible for human acquisition of relevant pathogens, including MRSA (Hardy et al., 2006; Sexton et al., 2006).

The production of coagulase and its plasma-clotting activity is a central diagnostic feature to distinguish staphylococcal strains in coagulase-positive staphylococci (CoPS) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (Becker et al., 2014). In addition to being key to diagnostics and group differentiation of Staphylococcus in CoPS and CoNS, coagulase is a virulence factor that leads to the cleavage of soluble fibrinogen to produce a fibrin coat in the surface of the bacteria, thus protecting it from phagocytosis and other host defenses (Powers and Wardenburg, 2014). Moreover, the polymorphisms of the coagulase-coding gene, coa, allows it to be explored in molecular typing techniques (Salehzadeh et al., 2016; Javid et al., 2018). However, because some populations of CoPS may not have the coa gene, while some CoNS present this gene, the applications of these methods are limited (Almeida et al., 2018). These coagulase-variable strains are more frequently found in some species than others, but their misdiagnosis may lead to unsuitable treatment of infections and control measures. This is especially significant when the detection of the pathogenic S. aureus relies on coagulase production and strains of these species do not produce coagulase, leading to isolate misidentification (Sundareshan et al., 2017). Strains of the CoNS S. chromogenes, S. xylosus, S. cohnii and S. agnetis have been reported to clot plasma, leading to misidentification of the pathogens causing mastitis in dairy animals (Taponen et al., 2012; Santos et al., 2016; Almeida et al., 2018). For that reason, researchers have relied on more accurate identification methods, including the sequencing of the 16S rRNA and the housekeeping genes rpoB, encoding the β subunit of RNA polymerase, as well as tuf, encoding the EF-tu elongation factor (Ghebremedhin et al., 2008; Li et al., 2012). Given its simplicity to perform and its cost effectiveness, matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) is emerging as a potential tool for microbial identification and diagnosis (Singhal et al., 2015). MALDI-TOF identification of staphylococci shows a good correlation with sequencing results, although the lack of standards for uncommon and recently identified species is still a bottleneck (Rossi et al., 2017b).

CoPS, with a special emphasis on S. aureus, responsible for several clinical infections, from those in skin and soft tissues to systemic disease processes like sepsis (Tong et al., 2015), are considered to be more pathogenic than CoNS. A plethora of virulence factors have been described and extensively reviewed for S. aureus, comprising molecules involved in tissue adhesion, immune evasion and host cell injury (Powers and Wardenburg, 2014). Proteins covalently anchored to the cell wall peptidoglycan may participate in not only biotic and abiotic surface adhesion, but also in biofilm formation and iron acquisition, among other functions (Foster et al., 2014). Moreover, a wide variety of toxins can be secreted, aiming to evade the defense mechanisms of the host (Otto, 2014). Other relevant pathogenic CoPS belong in the Staphylococcus indermedius group (SIG). This group includes zoonotic pathogens typically associated with dog bites, i.e., S. intermedius, S. pseudintermedius, the recently described S. cornubiensis (Murray et al., 2018), and S. delphini, first isolated from skin lesions of dolphins (Varaldo et al., 1988).

The increasing recognition of the importance of S. pseudintermedius as a zoonotic pathogen has boosted investigations on virulence factors involving infections caused by this bacterium. Among them, pore-forming toxins seem to play a pivotal role in the characteristic skin infections (Abouelkhair et al., 2018; Maali et al., 2018). Because many of these virulence factors are encoded in mobile genetic elements (MGE) with extensive variation in gene content, different strains strongly vary in their virulence arsenal (Otto, 2014; Moon et al., 2015).

The CoNS constitute the vast majority of staphylococci, comprising more than 80% of the species described to date (Becker et al., 2014; Parte, 2018). Historically considered as harmless inhabitants of the human and animal microbiota, in the past two decades CoNS have emerged as the major nosocomial pathogens, mostly associated with invasive medical devices (Becker et al., 2014), being particularly threatening to immunocrompromised individuals (Morfin-Otero et al., 2012). Among these opportunistic pathogens, S. epidermidis is the most frequent cause of nosocomial infections (Gomes et al., 2014), followed by S. haemolyticus (Czekaj et al., 2015). The infections caused by these species are particularly important because they are difficult to treat, since device colonization is usually related to biofilm formation, which can lead to complications, including sepsis, endocarditis, and a wide variety of local infections derived from the bloodstream spreading of bacteria (Chang et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2018).

Commensal and opportunistic staphylococci acting as gene reservoirs

Staphylococcus species that are usually considered as harmless inhabitants of the microbiota of animals and humans beings, like most CoNS, lack nearly all of the virulence factors described for S. aureus and do not encode many known specific factors, apart from a limited amount of toxins and exoenzymes (Zhang et al., 2003). Their emergent threat comes from the fact that these bacteria may carry a huge amount of antimicrobial resistance genes located in MGEs (Gomes et al., 2014; Czekaj et al., 2015; Hosseinkhani et al., 2018).

Multidrug-resistant CoNS have been increasingly linked to infections outbreaks in healthcare units (Chang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018), including strains that are not only isolated from patients, but also from healthcare workers, and the environment (Widerstrom et al., 2016). Microbiome studies reveal clonal staphylococcal strains wide ability to colonize diverse hosts and surrounding environments (Song et al., 2013; Lax et al., 2014). Their widespreadness can lead to infections caused by multidrug resistant strains in both humans and animals by species that are atypical pathogens in one of the hosts. Dutta et al. (2018), for example, have recently isolated Staphylococcus pettenkoferi strains causing peritonitis from a domestic cat. This species was discovered in 2002 in various human patients showing multiple clinical manifestations, but had never been isolated from animals before. Likewise, as aforementioned, the typical canine staphylococcal species S. pseudintermedius can occasionally cause disease in human beings as well (Riegel et al., 2011; Lozano et al., 2017).

This long overlooked exchange of microorganisms and antimicrobial resistance between different hosts and environments is now clear, and strains isolated from humans and domestic animals carry several resistance genes in common (Schwarz et al., 2018). Even though some antimicrobials have their use restricted to treat infections in animals, many multidrug resistance genes in staphylococci isolated from them confer resistance to antimicrobial agents that are highly important in human medicine (Wendlandt et al., 2015). Then, even if one staphylococcal species is not a common pathogen, it can be a potential threat, because it may be capable of transferring antimicrobial resistance genes to more pathogenic species, such as S. aureus, thereby enhancing its capacity to resist drug therapy (Haaber et al., 2017). For that reason, some CoNS have been suggested to act as antimicrobial genes reservoirs within the Staphylococcus genus (Cafini et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2017a).

The acquisition of antimicrobial resistance genes is mainly credited to the occurrence of conjugation and bacteriophage transduction and the presence of dozens of insertion sequences in staphylococcal genomes, whose rearrangements contribute to genome plasticity and strains’ phenotypic diversification (Takeuchi et al., 2005; Haaber et al., 2017). For a while, bacteriophage transduction was perceived as the primary route of horizontal gene transfer between staphylococci, while conjugation was believed to play only a minor role in the evolution of this genus, given the scarcity of mobilization and conjugation loci in staphylococcal plasmids (Ramsay et al., 2016; Haaber et al., 2017). In fact, only 5% of sequenced staphylococcal plasmids harbor genes required for autonomous transfer by conjugation, which is contrasting with the abundant evidences for horizontal transfer of plasmids between different lineages and species of Staphylococcus (Ramsay et al., 2016).

However, new mechanisms of transference of those types of plasmids have been discovered and probably explain the extensive plasmid transfer within the genus. These mechanisms include conjugation mediated by integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs), also referred to as conjugative transposons (Lee et al., 2012), in trans recognition of multiple variants of the canonic origin of transfer (oriT) by some conjugative plasmids (O’Brien et al., 2015b), and the activity of novel conjugative plasmids described in community isolates of S. aureus that are capable of mobilizing unrelated non-conjugative plasmids (O’Brien et al., 2015a).

The Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec), a genomic island that encodes resistance to methicillin and nearly all other beta-lactam antibiotics, is also a protagonist in the emergence of resistant strains. Analyses of numerous SCCmec sequences indicate that this mobile genetic element evolved by recombination and assembly events involving an ancestral SCCmec III cassette between strains of the S. sciuri group and the species S. vitulinus and S. fleurettii, which were then transferred to S. aureus and other species (Rolo et al., 2017), with CoNS acting as their central reservoirs (Saber et al., 2017).

Our group has demonstrated the transference of high molecular weight plasmids carrying the mupA gene for mupirocin resistance from S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and S. haemolyticus strains, from either human or canine origin, to another S. aureus strain (Bastos et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2016, 2018). Mupirocin resistance spreading is alarming, since this drug, which is used as an intranasal ointment by healthcare workers, can significantly reduce the occurrence of nosocomial infections caused by MRSA (Patel et al., 2009). Similarly, Cafini et al. (2016) demonstrated the transfer of linezolid resistance mediated by the cfr gene through plasmids, between S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and Enterococcus spp. isolates from Japan. Enterococcus spp. is also a protagonist of nosocomial infections and has been pointed out to participate in plasmid exchange with MRSA, through which resistance to the last-resource antibiotic vancomycin appears to be acquired (Kohler et al., 2018). A study performed by Meric et al. (2015) with hundreds of genomes of S. aureus and S. epidermidis showed that these species share only about half of their pan genome, but there was a considerable sharing of mobile genetic elements between the two species, in particular genes associated with pathogenic islands and the SCCmec.

Biofilm formation, a characteristic feature of many CoNS (Barros et al., 2015; Buttner et al., 2015), seems to provide the ideal environment for the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer (Madsen et al., 2012).

Biofilms as the perfect place for horizontal gene transfer among staphylococci

Bacterial biofilms are dense surface-associated cellular communities embedded in a protective self-produced matrix of exopolysaccharides, whose development confers new properties to its inhabitants (Black and Costerton, 2010, Flemming et al., 2016). Biofilms feature a social cooperation between bacteria that enhances nutrient uptake and distribution and, given its protective matrix, hinders the exposure to antimicrobials and host defenses, thus increasing survival (Flemming et al., 2016). Hence, biofilm formation plays a fundamental role in virulence.

Although the biofilm mechanisms involved in resistance to host defenses are not entirely understood, they include spatially limiting the access of leukocytes and their products to the target cells, suppression of leukocyte effector functions and cell-cell communication to increase resistance (Leid, 2009). Reducing membrane permeability also contributes to limit the entrance of antimicrobials (Liu et al., 2000). However, the presence of antibiotics that affect the Staphylococcus cell wall have been shown to modulate natural transformation in a process that seems to be dependent of the alternative sigma fator H, SigH (Thi et al., 2016). In fact, the expression of SigH-controlled genes makes S. aureus cells competent for transformation by plasmids or chromosomal DNA (Morikawa et al., 2012), which in turn increases the probability of plasmid exchange between the cells within the biofilm. Liu et al. (2017) demonstrated that the presence of many antibiotics induces the expression of the ccrC1 gene, involved with the excision of the SCCmec from the bacterial chromosome, thus triggering its transfer.

Overall, the high cellular density of biofilms, increased concentration of exogenous DNA, enhanced cell competence, stabilization of cell-cell contact by the matrix and even the biofilm architecture, that facilitates the dispersion of MGEs, may contribute to horizontal gene transfer (Madsen et al., 2012; Savage et al., 2013). The fact that more transconjugants are produced after filter-matings, when compared with planktonic cells mating, indicates the importance of biofilms for the transfer of MGEs (Madsen et al., 2012). It has been shown that S. aureus biofilms can drastically increase the rates of conjugation and transformation of plasmids containing resistance to multiple drugs (Savage et al., 2013).

As observed for many bacteria, during biofilm maturation S. aureus can suffer lysis and release its genomic DNA, producing the so-called external DNA (eDNA), which is a major component of the matrix of biofilms established by this bacterium (Sugimoto et al., 2018). The eDNA adsorbs to the surface of a single cell in long loop structures, which act as an adhesive substance that facilitates cell attachment, in addition to influence the hydrophobicity of the bacterial cell surface (Okshevsky and Meyer, 2015). Furthermore, in S. epidermidis, eDNA production reduces the depth of vancomycin penetration, as the matrix-embed and negatively charged DNA interacts with positive charges of the antimicrobials (Doroshenko et al., 2014). Moreover, the eDNA released by the cells to constitute the biofilm matrix is also available for horizontal gene transfer by transformation to competent cells in the community (Hannan et al., 2010; Vorkapic et al., 2016).

The dispersion of MGEs and eDNA is likely facilitated by the empty spaces within biofilms, which also function as channels that allow the flowing of fluids and the consequent dispersion of nutrients and oxygen to all cells. Studies indicate that this biofilm architecture is influenced by the production of biosurfactant compounds by the adherent bacteria (Davey et al., 2003). Consistent with this, we have recently shown that S. haemolyticus strains are capable of producing biosurfactants that affect biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces (Rossi et al., 2016). Likewise, surfactant peptides produced by S. epidermidis control biofilm maturation and detachment from colonized catheters (Wang et al., 2011).

While, as abovementioned, CoNS lack most of the S. aureus virulence factors, biofilm formation is a major feature of S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus, as well as of other CoNS, such as S. saprophyticus, S. hominis and S. cohnii. This phenotype is positively correlated with widespread antimicrobial resistance (Allori et al., 2006; Czekaj et al., 2015).

The CRISPR paradox in gene-reservoirs’ staphylococci

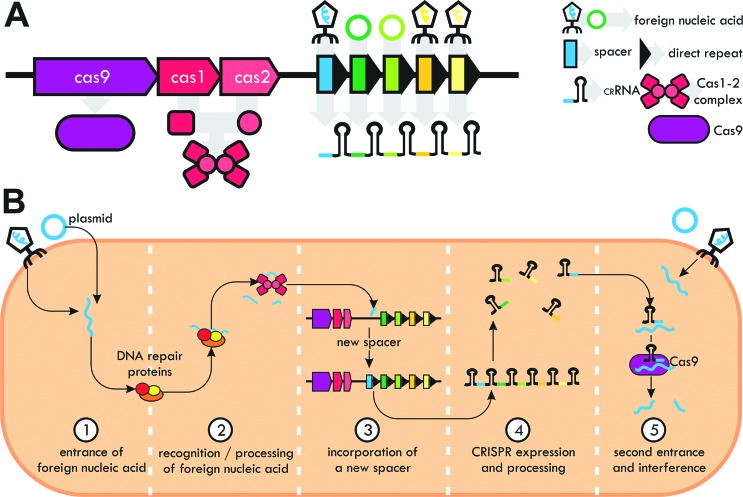

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs), allegedly present in the genomes of close to 90% of archaea and 50% of bacteria, are a prokaryotic evolutionary defense response to the preponderance of bacteriophages in the biosphere, acting as an interference system against foreign nucleic acids (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010). The CRISPR locus is composed of direct repeats of palindromic sequences interspersed with small sequences called spacers, which are fragments of exogenous sequences (Figure 1A). A functional CRISPR system has adjacent proteins (CRISPR-associated proteins, Cas), responsible for the process of recognition of foreign nucleic acids and the interference against invasive genetic elements (Horvath and Barrangou, 2010).

Figure 1. Features of CRISPR systems. (A) Main structure of a CRISPR system. For simplicity, a type II system, containing only the Cas9 protein as the interference effector, is displayed. (B) Steps of a CRISPR system activity, from foreign nucleic acid recognition and spacer incorporation (a step called adaptation) to interference.

CRISPR interference begins with the entrance of an exogenous DNA or RNA in the bacterial cell, which is processed into small fragments by repair proteins, like those of the RecBCD complex (Amitai and Sorek, 2016), and later recognized by a complex of universal Cas1-2 proteins, which incorporates a fragment of the invader nucleic acid in the CRISPR locus as a new spacer (Figure 1B). The CRISPR locus is expressed as a long transcript that is processed, either by Cas proteins or intrinsic RNases, into small RNAs referred to as CRISPR-RNAs (crRNAs). Each crRNA is made of a fragment of the original direct repeat and the spacer, whose complementarity to foreign mobile genetic elements is the basis of the interference process, fulfilled with the activity of another Cas protein (like Cas9), or Cas complexes (van der Oost et al., 2014).

Marraffini and Sontheimer (2008) described a S. epidermidis CRISPR containing a spacer whose sequence was homologous to a region of the nes gene, coding a nickase found in virtually every staphylococcal conjugative plasmid sequenced. Consistently, this CRISPR prevented conjugation and transformation from happening, while the removal of the spacer allowed plasmid uptake. Later, Hatoum-Aslan et al. (2014) constructed mutants for all the nine cas/csm genes of the type III-A system in Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62a and showed that many mutations affected interference by impacting the interference complex formation or the crRNA biogenesis. At least 4% of the spacers within staphylococcal CRISPRs are identical to publicly available plasmid sequences, thus demonstrating their antiplasmid activity (Rossi et al., 2017a). This percentage may be underrated due to under-sampling of mobile genetic elements and, as a consequence, their relative scarcity in public databases (Mojica et al., 2005).

Since CRISPR-Cas systems were believed to exist in roughly 50% of bacteria, and given its antiplasmid activity, it is supposed to highly impact horizontal gene transfer among staphylococci. However, a study performed by Cao et al. (2016) with hundreds of S. aureus clinical isolates from China revealed that less than 1% of them harbored a complete arrangement of cas genes. Later, our group analyzed the genomes of dozens of CoNS of 15 species and also found that less than 15% of them carried CRISPRs and cas genes (Rossi et al., 2017a). Regardless of how abundant CRISPRs really are among Staphylococcus isolates, they are clearly rarer than previously thought, which is consistent with the role of staphylococcal as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes.

Because spacers are incorporated in the CRISPR locus following an organized and thus chronological order (van der Oost et al., 2014), their sequences can be explored as molecular clocks to reveal the history of genetic invasion of a given isolate, and even to study the epidemiologic connection between different strains carrying a CRISPR of a common origin. With that prerogative, we explored the spacer sequences of CRISPRs located within SCCmec elements from different Staphylococcus species. As indicated by the high sequence identity between the SCCmecs, the identical sequence and organization of spacers evidenced that the mobile genetic element had been transferred between strains of canine S. pseudintermedius and S. schleiferi, and then to strains of S. capitis and S. aureus isolated from humans (Rossi et al., 2017a; Rossi et al., 2019).

Concluding remarks

Most Staphylococcus species lack many of the S. aureus virulence factors and, because they are less frequently isolated from infectious processes, their impact in pathogenesis is usually overlooked. However, sequence and experimental evidences of horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes between them, favored by their capacity of forming biofilms and the scarcity of restrictive CRISPR-systems, show that these bacteria participate actively in the process of drug resistance spreading. Moreover, the fact that we exchange microbiota with our surroundings, makes it imperative that epidemiologic studies and strategies to control the advance of antimicrobial resistance consider the integrated nature of the relationship between human beings, animals, and the environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the financial support from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ, grants E-26/203.037/2016, E-26/010.101056/2018 and E-26/201.451/2014), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant 305940/2018-0) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior Programa de Excelência Acadêmica – Finance Code 001 (CAPES ProEx, grant 23038.002486/2018-26).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Célia Maria de Almeida Soares

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Author Contributions

CCR and MGM conceived and designed the study, CCR, MFP and MGM analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

References

- Abouelkhair MA, Bemis DA, Giannone RJ, Frank LA, Kania SA. Characterization of a leukocidin identified in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius . PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allori MC, Jure MA, Romero C, Castillo ME. Antimicrobial resistance and production of biofilms in clinical isolates of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus strains. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1592–1596. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida CC, Pizauro LJL, Soltes GA, Slavic D, Ávila FA, Pizauro JM, Janet IM. Some coagulase negative Staphylococcus spp. isolated from buffalo can be misidentified as Staphylococcus aureus by phenotypic and Sa442 PCR methods. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:346. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3449-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitai G, Sorek R. CRISPR-Cas adaptation: Insights into the mechanism of action. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros EM, Lemos M, Souto-Padron T, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus haemolyticus . Curr Microbiol. 2015;70:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos MC, Mondino PJ, Azevedo ML, Santos KR, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Molecular characterization and transfer among Staphylococcus strains of a plasmid conferring high-level resistance to mupirocin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s100960050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:870–926. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00109-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CE, Costerton JW. Current concepts regarding the effect of wound microbial ecology and biofilms on wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner H, Mack D, Rohde H. Structural basis of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation: Mechanisms and molecular interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:14. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello FC, Godfrey HP, Tomova A, Ivanova L, Dolz H, Millanao A, Buschmann AH. Antimicrobial use in aquaculture re-examined: Its relevance to antimicrobial resistance and to animal and human health. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:1917–1942. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafini F, Nguyen le TT, Higashide M, Roman F, Prieto J, Morikawa K. Horizontal gene transmission of the cfr gene to MRSA and Enterococcus: Role of Staphylococcus epidermidis as a reservoir and alternative pathway for the spread of linezolid resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:587–592. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Gao CH, Zhu J, Zhao L, Wu Q, Li M, Sun B. Identification and functional study of type III-A CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus . Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PH, Liu TP, Huanga PY, Lin SY, Lin JF, Yeh CF, Chang SC, Wu TS, Lu JJ. Clinical features, outcomes, and molecular characteristics of an outbreak of Staphylococcus haemolyticus infection, among a mass-burn casualty patient group, in a tertiary center in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infec. 2018;51:847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekaj T, Ciszewski M, Szewczyk EM. Staphylococcus haemolyticus – an emerging threat in the twilight of the antibiotics age. Microbiology. 2015;161:2061–2068. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ME, Caiazza NC, O’Toole GA. Rhamnolipid surfactant production affects biofilm architecture in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1027–1036. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1027-1036.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriese LA, Vancanneyt M, Baele M, Vaneechoutte M, De Graef E, Snauwaert C, Cleenwerck I, Dawyndt P, Swings J, Decostere A, Haesebrouck F. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species from animals. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1569–1573. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroshenko N, Tseng BS, Howlin RP, Deacon J, Wharton JA, Thurner PJ, Gilmore BF, Parsek MR, Stoodley P. Extracellular DNA impedes the transport of vancomycin in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms preexposed to subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:7273–7282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03132-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta TK, Chakraborty S, Das M, Mandakini R, Vanrahmlimphuii Roychoudhury P, Ghorai S, Behera SK. Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus pettenkoferi isolated from cat in India. Vet World. 2018;11:1380–1384. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.1380-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald JR. The Staphylococcus intermedius group of bacterial pathogens: Species re-classification, pathogenesis and the emergence of meticillin resistance. Vet Dermatol. 2009;20:490–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2009.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Hook M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: The many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus . Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremedhin B, Layer F, König W, König B. Genetic classification and distinguishing of Staphylococcus species based on different partial gap, 16s rRNA, hsp60, rpoB, sodA, and tuf gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1019–1025. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes F, Teixeira P, Oliveira R. Staphylococcus epidermidis as the most frequent cause of nosocomial infections: Old and new fighting strategies. Biofouling. 2014;30:131–141. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.848858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardabassi L, Schwarz S, Lloyd DH. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:321–332. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaber J, Penades JR, Ingmer H. Transfer of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus . Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan S, Ready D, Jasni AS, Rogers M, Pratten J, Roberts AP. Transfer of antibiotic resistance by transformation with eDNA within oral biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy KJ, Oppenheim BA, Gossain S, Gao F, Hawkey PM. A study of the relationship between environmental contamination with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and patients’ acquisition of MRSA. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:127–132. doi: 10.1086/500622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A, Maniv I, Samai P, Marraffini LA. Genetic characterization of antiplasmid immunity through a type III-A CRISPR-Cas system. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:310–317. doi: 10.1128/JB.01130-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild T, Stepanovic S, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J. Staphylococcus stepanovicii sp. nov., a novel novobiocin-resistant oxidase-positive staphylococcal species isolated from wild small mammals. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science. 2010;327:167–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1179555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinkhani F, Tammes Buirs M, Jabalameli F, Emaneini M, van Leeuwen WB. High diversity in SCCmec elements among multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus strains originating from paediatric patients; characterization of a new composite island. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67:915–921. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javid F, Taku A, Bhat MA, Badroo GA, Mudasir M, Sofi TA. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus based on coagulase gene. Vet World. 2018;11:423–430. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.423-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LJ, Anderson LR, Blackmore CG, Blackwell MJ, Lautner EA, Marcus LC, Meyer TE, Monath TP, Nave JE, Ohle J, et al. Executive summary of the AVMA One Health Initiative Task Force report. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:259–261. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock R, Schaumburg F, Mellmann A, Koksal M, Jurke A, Becker K, Friedrich AW. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as causes of human infection and colonization in Germany. PloS One. 2013;8:e55040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler V, Vaishampayan A, Grohmann E. Broad-host-range Inc18 plasmids: Occurrence, spread and transfer mechanisms. Plasmid. 2018;99:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraker ME, Stewardson AJ, Harbarth S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax S, Smith DP, Hampton-Marcell J, Owens SM, Handley KM, Scott NM, Gibbons SM, Larsen P, Shogan BD, Weiss S, et al. Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science. 2014;345:1048–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.1254529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan R, Sridhar D, Blaser M, Wang M, Woolhouse M. Achieving global targets for antimicrobial resistance. Science. 2016;353:874–875. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS, de Lencastre H, Garau J, Kluytmans J, Malhotra-Kumar S, Peschel A, Harbarth S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18033. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CA, Thomas J, Grossman AD. The Bacillus subtilis conjugative transposon ICEBs1 mobilizes plasmids lacking dedicated mobilization functions. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3165–3172. doi: 10.1128/JB.00301-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leid JG. Bacterial biofilms resist key host defenses. Microbe. 2009;4:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Xing J, Li B, Wang P, Liu J. Use of tuf as a target for sequence-based identification of Gram-positive cocci of the genus Enterococcus, Streptococcus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and Lactococcus . Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Arias CA, Aitken SL, Galloway Pena J, Panesso D, Chang M, Diaz L, Rios R, Numan Y, Ghaoui S, et al. Clonal emergence of invasive multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis deconvoluted via a combination of whole-genome sequencing and microbiome analyses. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:398–406. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Wu Z, Xue H, Zhao X. Antibiotics trigger initiation of SCCmec transfer by inducing SOS responses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3944–3952. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Ng C, Ferenci T. Global adaptations resulting from high population densities in Escherichia coli cultures. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4158–4164. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4158-4164.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano C, Rezusta A, Ferrer I, Perez-Laguna V, Zarazaga M, Ruiz-Ripa L, Revillo MJ, Torres C. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius human infection cases in Spain: Dog-to-human transmission. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:268–270. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maali Y, Badiou C, Martins-Simoes P, Hodille E, Bes M, Vandenesch F, Lina G, Diot A, Laurent F, Trouillet-Assant S. Understanding the virulence of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius: a major role of pore-forming toxins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:221. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen JS, Burmolle M, Hansen LH, Sorensen SJ. The interconnection between biofilm formation and horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:183–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science. 2008;322:1843–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.1165771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BM, Levy SB. Food animals and antimicrobials: Impacts on human health. Clin Microbiol Reviews. 2011;24:718–733. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meric G, Miragaia M, de Been M, Yahara K, Pascoe B, Mageiros L, Mikhail J, Harris LG, Wilkinson TS, Rolo J, et al. Ecological overlap and horizontal gene transfer in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis . Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:1313–1328. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon BY, Park JY, Hwang SY, Robinson DA, Thomas JC, Fitzgerald JR, Park YH, Seo KS. Phage-mediated horizontal transfer of a Staphylococcus aureus virulence-associated genomic island. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9784. doi: 10.1038/srep09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfin-Otero R, Martinez-Vazquez MA, Lopez D, Rodriguez-Noriega E, Garza-Gonzalez E. Isolation of rare coagulase-negative isolates in immunocompromised patients: Staphylococcus gallinarum, Staphylococcus pettenkoferi and Staphylococcus pasteuri . Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2012;42:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K, Takemura AJ, Inose Y, Tsai M, Nguyen Thi le T, Ohta T, Msadek T. Expression of a cryptic secondary sigma factor gene unveils natural competence for DNA transformation in Staphylococcus aureus . PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni P, Pisoni G, Antonini M, Ruffo G, Carli S, Varisco G, Boettcher P. Subclinical mastitis and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus caprae and Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated from two Italian goat herds. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:1694–1704. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72841-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AK, Lee J, Bendall R, Zhang L, Sunde M, Schau Slettemeas J, Gaze W, Page AJ, Vos M. Staphylococcus cornubiensis sp. nov., a member of the Staphylococcus intermedius Group (SIG) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:3404–3408. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova D, Pantucek R, Petras P, Koukalova D, Sedlacek I. Occurance of Staphylococcus nepalensis strains in different sources including human clinical material. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;263:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova D, Sedlacek I, Pantucek R, Stetina V, Svec P, Petras P. Staphylococcus equorum and Staphylococcus succinus isolated from human clinical specimens. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:523–528. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien FG, Ramsay JP, Monecke S, Coombs GW, Robinson OJ, Htet Z, Alshaikh FA, Grubb WB. Staphylococcus aureus plasmids without mobilization genes are mobilized by a novel conjugative plasmid from community isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:649–652. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien FG, Yui Eto K, Murphy RJ, Fairhurst HM, Coombs GW, Grubb WB, Ramsay JP. Origin-of-transfer sequences facilitate mobilisation of non-conjugative antimicrobial-resistance plasmids in Staphylococcus aureus . Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7971–7983. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev Antimicrob Resist. 2014;2014:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Okshevsky M, Meyer RL. The role of extracellular DNA in the establishment, maintenance and perpetuation of bacterial biofilms. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2015;41:341–352. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2013.841639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira WF, Silva PMS, Silva RCS, Silva GMM, Machado G, Coelho LCBB, Correia MTS. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis infections on implants. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. Coagulase-negative staphylococci as reservoirs of genes facilitating MRSA infection: Staphylococcal commensal species such as Staphylococcus epidermidis are being recognized as important sources of genes promoting MRSA colonization and virulence. Bioessays. 2013;35:4–11. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;17:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parte AC. LPSN - List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (bacterio.net), 20 years on. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:1825–1829. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JB, Gorwitz RJ, Jernigan JA. Mupirocin resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:935–941. doi: 10.1086/605495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmann P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:557–596. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00064-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers ME, Wardenburg JB. Igniting the Fire: Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors in the pathogenesis of sepsis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003871. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JP, Kwong SM, Murphy RJ, Yui Eto K, Price KJ, Nguyen QT, O’Brien FG, Grubb WB, Coombs GW, Firth N. An updated view of plasmid conjugation and mobilization in Staphylococcus . Mob Genet Elements. 2016;6:e1208317. doi: 10.1080/2159256X.2016.1208317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel P, Jesel-Morel L, Laventie B, Boisset S, Vandenesch F, Prevost G. Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from animals causing human endocarditis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TP, Bu DP, Carrique-Mas J, Fevre EM, Gilbert M, Grace D, Hay SI, Jiwakanon J, Kakkar M, Kariuki S, et al. Antibiotic resistance is the quintessential One Health issue. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:377–380. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trw048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolo J, Worning P, Nielsen JB, Bowden R, Bouchami O, Damborg P, Guardabassi L, Perreten V, Tomasz A, Westh H, et al. Evolutionary origin of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02302–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02302-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, Ferreira NC, Coelho ML, Schuenck RP, Bastos MC, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Transfer of mupirocin resistance from Staphylococcus haemolyticus clinical strains to Staphylococcus aureus through conjugative and mobilizable plasmids. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:fnw121. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, Souza-Silva T, Araujo-Alves AV, Giambiagi-deMarval M. CRISPR-Cas systems features and the gene-reservoir role of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1545. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, da Silva Dias I, Muniz IM, Lilenbaum W, Giambiagi-deMarval M. The oral microbiota of domestic cats harbors a wide variety of Staphylococcus species with zoonotic potential. Vet Microbiol. 2017;201:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, de Oliveira LL, de Carvalho Rodrigues D, Urmenyi TP, Laport MS, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Expression of the stress-response regulators CtsR and HrcA in the uropathogen Staphylococcus saprophyticus during heat shock. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10482-017-0881-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, Salgado BAB, Barros EM, de Campos Braga PA, Eberlin MN, Lilenbaum W, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Identification of Staphylococcus epidermidis with transferrable mupirocin resistance from canine skin. Vet J. 2018;235:70–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi CC, Andrade-Oliveira AL, Giambiagi-deMarval M. CRISPR tracking reveals global spreading of antimicrobial resistance genes by Staphylococcus of canine origin. Vet Microbiol. 2019;232:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscher C, Lubke-Becker A, Wleklinski CG, Soba A, Wieler LH, Walther B. Prevalence of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from clinical samples of companion animals and equidaes. Vet Microbiol. 2009;136:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saber H, Jasni AS, Jamaluddin T, Ibrahim R. A Review of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types in coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) species. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24:7–18. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.5.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehzadeh A, Zamani H, Langeroudi MK, Mirzaie A. Molecular typing of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus strains associated to biofilm based on the coagulase and protein A gene polymorphisms. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016;19:1325–1330. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2016.7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos DC, Lange CC, Avellar-Costa P, Santos KRN, Brito MAVP, Giambiagi-deMarval M. Staphylococcus chromogenes, a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species that can clot plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1372–1375. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03139-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kikuchi K, Tanaka Y, Takahashi N, Kamata S, Hiramatsu K. Reclassification of phenotypically identified Staphylococcus intermedius strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2770–2778. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00360-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage VJ, Chopra I, O’Neill AJ. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms promote horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1968–1970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02008-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S, Fessler AT, Loncaric I, Wu C, Kadlec K, Wang Y, Shen J. Antimicrobial resistance among staphylococci of animal origin. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6:4. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.arba-0010-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton T, Clarke P, O’Neill E, Dillane T, Humphreys H. Environmental reservoirs of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in isolation rooms: correlation with patient isolates and implications for hospital hygiene. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld EK, Graham J, Price LB. Industrial food animal production, antimicrobial resistance, and human health. Ann Rev Public Health. 2008;29:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal N, Kumar M, Kanaujia PK, Virdi JS. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: An emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:791. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SJ, Lauber C, Costello EK, Lozupone CA, Humphrey G, Berg-Lyons D, Caporaso JG, Knights D, Clemente JC, Nakielny S, et al. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. eLife. 2013;2:e00458. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spergser J, Wieser M, Taubel M, Rossello-Mora RA, Rosengarten R, Busse HJ. Staphylococcus nepalensis sp. nov., isolated from goats of the Himalayan region. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:2007–2011. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto S, Sato F, Miyakawa R, Chiba A, Onodera S, Hori S, Mizunoe Y. Broad impact of extracellular DNA on biofilm formation by clinically isolated Methicillin-resistant and -sensitive strains of Staphylococcus aureus . Sci Rep. 2018;8:2254. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20485-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundareshan S, Isloor S, Babu YH, Sunagar R, Sheela P, Tiwari JG, Wyryah CB, Mukkur TK, Hegde NR. Isolation and molecular identification of rare coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus variants isolated from bovine milk samples. Indian J Comp Microbiol Immunol Infect Dis. 2017;38:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi F, Watanabe S, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Ito T, Morimoto Y, Kuroda M, Cui L, Takahashi M, Ankai A, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus haemolyticus uncovers the extreme plasticity of its genome and the evolution of human-colonizing staphylococcal species. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7292–7308. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7292-7308.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taponen S, Supre K, Piessens V, Van Coillie E, De Vliegher S, Koort JM. Staphylococcus agnetis sp. nov., a coagulase-variable species from bovine subclinical and mild clinical mastitis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:61–65. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.028365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thi LTN, Romero VM, Morikawa K. Cell wall-affecting antibiotics modulate natural transformation in SigH-expressing Staphylococcus aureus . J Antibiot. 2016;69:464–466. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG. Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Alvarez C, Chiquete-Felix N, Contreras-Zentella M, Guerrero-Castillo S, Pena A, Uribe-Carvajal S. Staphylococcus epidermidis: Metabolic adaptation and biofilm formation in response to different oxygen concentrations. Pathog Dis. 2016;74:ftv111. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Laxminarayan R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:742–750. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP, Teillant A, Laxminarayan R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Oost J, Westra ER, Jackson RN, Wiedenheft B. Unravelling the structural and mechanistic basis of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:479–492. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoovels L, Vankeerberghen A, Boel A, Van Vaerenbergh K, de Beenhouwer H. First case of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection in a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4609–4612. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01308-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhaeghen W, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F, Butaye P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food production animals. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:606–625. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809991567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varaldo PE, Kilpper-Bälz R, Biavasco F, Satta G, Schleifer KH. Staphylococcus delphini sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species isolated from dolphins. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1988;38:436–439. [Google Scholar]

- Vorkapic D, Pressler K, Schild S. Multifaceted roles of extracellular DNA in bacterial physiology. Curr Genet. 2016;62:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00294-015-0514-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Khan BA, Cheung GY, Bach TH, Jameson-Lee M, Kong KF, Queck SY, Otto M. Staphylococcus epidermidis surfactant peptides promote biofilm maturation and dissemination of biofilm-associated infection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:238–248. doi: 10.1172/JCI42520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendlandt S, Shen J, Kadlec K, Wang Y, Li B, Zhang WJ, Fessler AT, Wu C, Schwarz S. Multidrug resistance genes in staphylococci from animals that confer resistance to critically and highly important antimicrobial agents in human medicine. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization . Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. WHO Document Production Services; Geneva: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Widerstrom M, Wistrom J, Edebro H, Marklund E, Backman M, Lindqvist P, Monsen T. Colonization of patients, healthcare workers, and the environment with healthcare-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis genotypes in an intensive care unit: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:743. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthing K, Pang S, Trott DJ, Abraham S, Coombs GW, Jordan D, McIntyre L, Davies MR, Norris J. Characterisation of Staphylococcus felis isolated from cats using whole genome sequencing. Vet Microbiol. 2018;222:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, Wang YX, Fu G, Yang J, Qin ZQ, Miao YG, Wang WY, Chen RS, et al. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228) Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek L, Ghosh A. Insects represent a link between food animal farms and the urban environment for antibiotic resistance traits. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:3562–3567. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00600-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]