Abstract

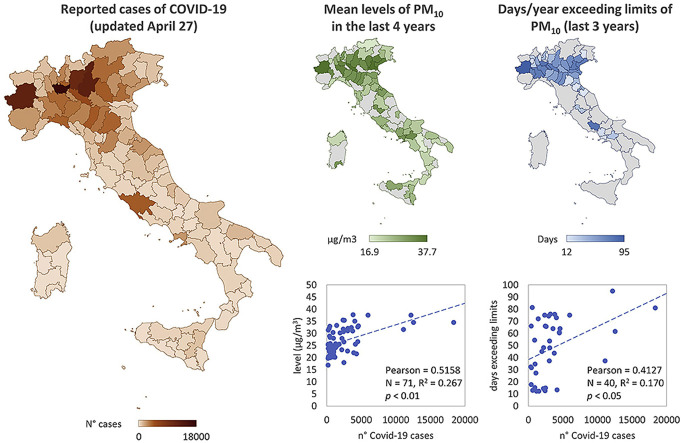

After the initial outbreak in China, the diffusion in Italy of SARS-CoV-2 is exhibiting a clear regional trend with more elevated frequency and severity of cases in Northern areas. Among multiple factors possibly involved in such geographical differences, a role has been hypothesized for atmospheric pollution. We provide additional evidence on the possible influence of air quality, particularly in terms of chronicity of exposure on the spread viral infection in Italian regions. Actual data on Covid-19 outbreak in Italian provinces and corresponding long-term air quality evaluations, were obtained from Italian and European agencies, elaborated and tested for possible interactions. Our elaborations reveal that, beside concentrations, the chronicity of exposure may influence the anomalous variability of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. Data on distribution of atmospheric pollutants (NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10) in Italian regions during the last 4 years, days exceeding regulatory limits, and years of the last decade (2010–2019) in which the limits have been exceeded for at least 35 days, highlight that Northern Italy has been constantly exposed to chronic air pollution. Long-term air-quality data significantly correlated with cases of Covid-19 in up to 71 Italian provinces (updated April 27, 2020) providing further evidence that chronic exposure to atmospheric contamination may represent a favourable context for the spread of the virus. Pro-inflammatory responses and high incidence of respiratory and cardiac affections are well known, while the capability of this coronavirus to bind particulate matters remains to be established. Atmospheric and environmental pollution should be considered as part of an integrated approach for sustainable development, human health protection and prevention of epidemic spreads but in a long-term and chronic perspective, since adoption of mitigation actions during a viral outbreak could be of limited utility.

Keywords: Covid-19, Atmospheric pollution, Chronic exposure, Viral diffusion, Italy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Covid-19 outbreak in Italy is exhibiting a clear regional trend.

-

•

Long-term air-quality data correlate with Covid-19 in the Italian provinces.

-

•

Chronic atmospheric pollution may favour coronavirus spreading.

-

•

Environmental pollution should be considered in epidemics prevention.

Chronic exposure to air pollutants might have a role in the spread of Covid-19 in Italian regions. Diffusion of Covid-19 in 71 Italian provinces correlated with long-term air-quality data.

In December 2019, several pneumonia cases were suddenly observed in the metropolitan city of Wuhan (China), as the result of infection to a novel coronavirus (Li et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). This virus was termed SARS-CoV-2 for its similarity with that responsible of the global epidemic Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) occurred between 2002 and 2003 (Xu et al., 2020). Patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection often experienced serious complications, including organ failure, septic shock, pulmonary oedema, severe pneumonia and acute respiratory stress syndrome which in several cases were fatal (Chen et al., 2020; Sohrabi et al., 2020). The most severe symptoms, requiring intensive care recovery, were generally observed in older individuals with previous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular, endocrine, digestive and respiratory diseases (Sohrabi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a). The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined this new syndrome with the acronym Covid-19 for Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Sohrabi et al., 2020; WHO, 2020a).

The drastic containment measures adopted by Chinese government did not prevent the diffusion of SARS-CoV-2, which in a few weeks has spread globally. Italy was the first country in Europe to be affected by the epidemic Covid-19, with an outbreak even larger than that originally observed in China (Fanelli and Piazza, 2020; Remuzzi and Remuzzi, 2020). Other European countries and United States rapidly registered an exponential growth of clinical cases, leading to restrictions and a global lockdown with evident social and economic repercussions (Cohen and Kupferschmidt, 2020; ECDC, 2020). The WHO has recently declared the pandemic state of Covid-19 with over 2.8 million of cases reported and over 201.000 victims worldwide (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020; WHO, 2020b; ECDC, 2020, accessed on April 27, 2020).

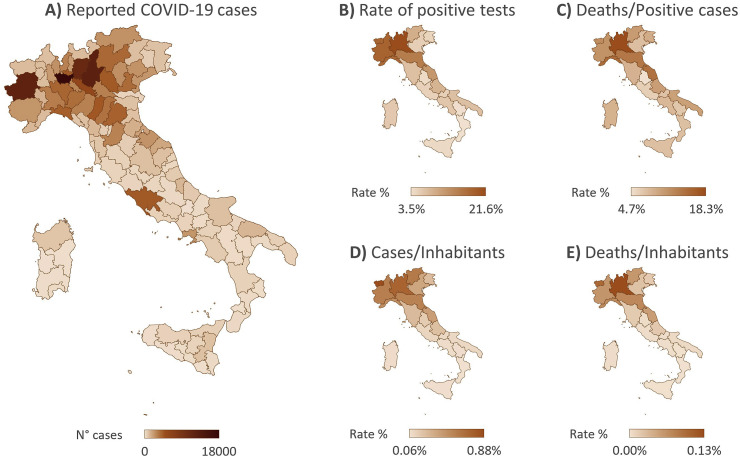

The ongoing epidemic trend in Italy immediately showed strong regional differences in the spread of infections, with most cases concentrated in the north of the country (Remuzzi and Remuzzi, 2020). The distribution of positive cases reported from February 24th to April 27th is summarized in Fig. 1 A: some areas of Lombardy and Piedmont clearly exceeded 10.000 cases, e.g. 18.371 at Milan, 12.564 at Brescia, 11.113 at Bergamo, 12.199 at Turin (data re-elaborated from the official daily reports of the Department of Civil Protection,ICPD, 2020, accessed on April 27, 2020). Also, the relative percentage distribution of the positive test rate (Fig. 1B) exhibit higher values in Northern Italy despite a certain uncertainty of data due to the different numbers and frequency of oropharyngeal swabs performed in various regions to test coronavirus positivity; mortality rate ranged from 18% in the northern regions to less than 5% in the others (Fig. 1C). Overall these trends closely parallel the rates of reported Covid-19 cases and of fatal events, expressed as percentage values normalized to the number of inhabitants for regional populations (Fig. 1D and E), further evidencing a significantly greater diffusion in Northern Italy, both in terms of number of infections and the severity of cases (mortality).

Fig. 1.

Regional distribution of Covid-19 outbreak in Italy (from February 24 to April 27, 2020). A) abundance of Covid-19 cases (absolute number); B) percentage of positive subjects referred to the number of performed tests (oropharyngeal swabs); C) mortality rate on the number of positive cases; D) percentage of Covid-19 cases normalized to the number of inhabitants; E) percentage of deaths normalized to the number of inhabitants. Data obtained and re-elaborated from the official daily reports of Italian Civil Protection Department (ICPD, 2020).

To explain such geographical trend, it was initially assumed that restrictions decided by government authorities after the first outbreak in Lombardy, had contained the infection preventing its rapid spread to the rest of the country. Some authors, however, from the clinical course of a large cohort of patients, have concluded that the epidemic coronavirus had been circulating in Italy for several weeks before the first recognized outbreak and the relative adopted containment measures (Cereda et al., 2020). In this respect, the differentiated occurrence of infection cannot be fully explained by the social confinement actions.

Since the presence of comorbidities appeared determinant for the aetiology and severity of the Covid-19 symptoms (Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Wu et al., 2020), the role of atmospheric pollution in contributing to the high levels of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy has been hypothesized (Conticini et al., 2020). Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and Covid-19 infection has been described also for the recent outbreak in China (Zhu et al., 2020). The adverse effects of air pollutants on human health are widely recognized in scientific literature, depending on various susceptibility factors such as age, nutritional status and predisposing conditions (Kampa and Castanas, 2008). Chronic exposure to the atmospheric pollution contributes to increased hospitalizations and mortality, primarily affecting cardiovascular and respiratory systems, causing various diseases and pathologies including cancer (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002; Kampa and Castanas, 2008). Among air pollutants, the current focus is mainly given on nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) and ozone (O3), frequently occurring at elevated concentrations in large areas of the planet.

The percentage of European population exposed to levels higher than the regulatory limits is about 7–8% for NO2, 6–8% for PM2.5, 13–19% for PM10 and 12–29% for O3 (EEA, 2019). Premature deaths due to acute respiratory diseases from such pollutants are estimated to be over to two million per year worldwide and 45.000 for Italy (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002; Huang et al., 2016; EAA, 2019; Watts et al., 2019).

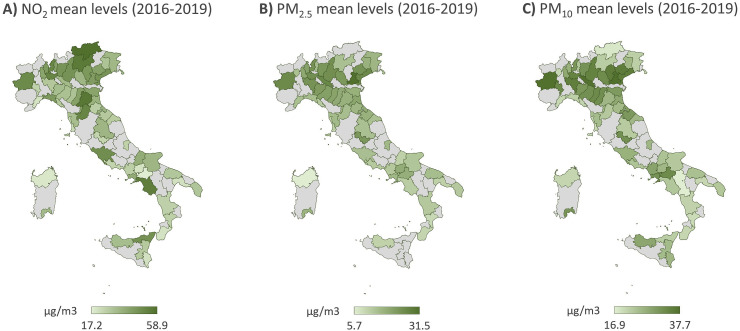

Here, we are providing additional evidence on the possible influence of air quality on the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Italian regions. Since the effects of air pollutants on human health not only depend on their concentrations but also, if not especially, on chronicity of exposure, we have elaborated the last four years (from 2016 to 2019, EEA, 2020) of regional distribution of NO2, PM2.5 and PM10 as presented in Fig. 2 . The highest atmospheric concentrations were clearly distributed in the Northern areas (Piedmont, Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna), in addition to urbanized cities, such as Rome and Naples.

Fig. 2.

Regional data on air quality levels: A) nitrogen dioxide (NO2); B) particulate matter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5); C) particulate matter of 2.5–10 μm (PM10). Data are referred to the means of values of last four years (2016–2019), expressed as μg/m3 (obtained and elaborated from the European Environmental Agency, accessed on 6 April, EEA, 2020).

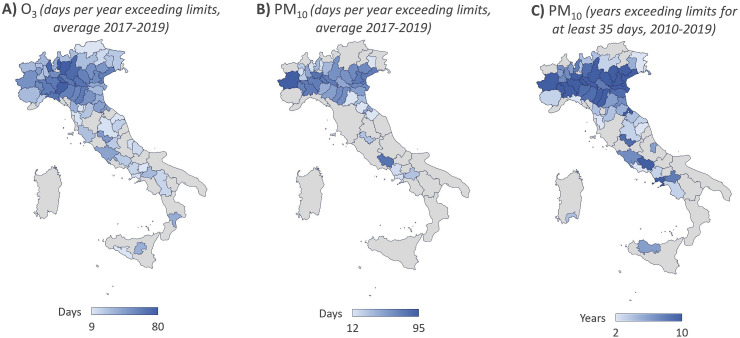

The long-term condition of population exposure is also revealed by the number of days per year in which the regulatory limits of O3 and PM10 are exceeded (Fig. 3 A–B): the critical situation of Northern Italy is reflected by values of up to 80 days of exceedance per year (average of the last three years, EAA, 2019). Worthy to remind, ozone is one of the main precursors for the formation of NO2, and chronic exposure to this contaminant for almost a quarter of a year is undoubtedly of primary importance. The chronic air pollution in Northern Italy is further represented by the number of years during the last decade (2010–2019) in which the limit value for PM10 (50 μg/m3 per day) has been exceeded for at least 35 days (Fig. 3C). Once again, these data would provide evidence that the whole Northern area below the Alpine arc has been constantly exposed to significantly higher levels of these contaminants.

Fig. 3.

Number of days per year exceeding the regulatory limits relating to A) ozone (O3) and to B) particulate matter (PM10), as average means of the last 3 years (2017–2019); C) number of years in which the PM10 limit was exceeded for at least 35 days per year, from 2010 to 2019. Data are obtained and elaborated from annual reports (Legambiente, 2018, 2019; 2020) and referred to the official statistics of the European Environmental Agency (EEA, 2019).

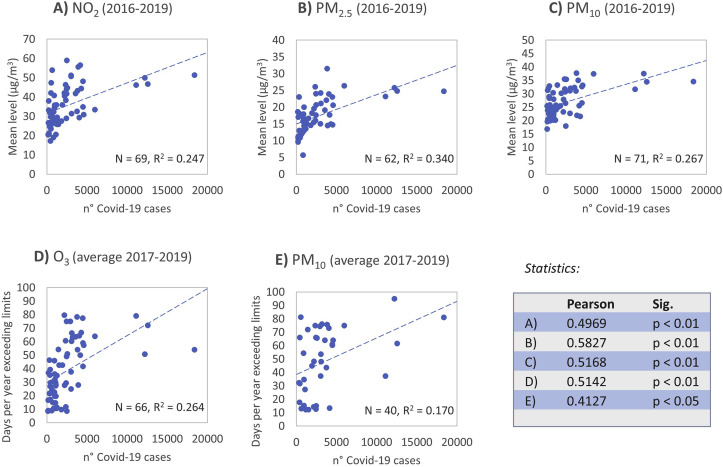

The hypothesis that atmospheric pollution may influence the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Italy was also tested from the relationships between the confirmed cases of Covid-19 in up to 71 Italian provinces (updated April 27, 2020) with the corresponding air quality data. The latter were expressed as average concentrations in the last 4 years of NO2, PM2.5 and PM10 (Fig. 4 A–C) and the number of days exceeding the regulatory limits (averages of the last 3 years) for O3 and PM10 (Fig. 4D–E). The always significant correlations provided further evidence on the role that chronic exposure to atmospheric contamination may have as a favourable context for the spread and virulence of the SARS-CoV-2 within a population subjected to a higher incidence of respiratory and cardiac affections.

Fig. 4.

Statistical correlation between the regional distribution of COVID-19 cases and the air quality parameters in Italy: incidence of Covid-19 cases vs levels of A) NO2, B) PM2.5 and C) PM10 (four years means); incidence of Covid-19 cases vs number of days per year exceeding regulatory limits of D) O3 and E) PM10 (three years means). Data obtained and elaborated from EEA (2019; 2020), ICPD (2020), and Legambiente (2018, 2019; 2020).

It is well known that exposure to atmospheric contaminants modulate the host’s inflammatory response leading to an overexpression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Gouda et al., 2018). Clear effects of Milan winter PM2.5 were observed on elevated production of interleukin IL-6 and IL-8 in human bronchial cells (Longhin et al., 2018), and also NO2 was shown to correlate with IL-6 levels on inflammatory status (Perret et al., 2017). The impairment of respiratory system and chronic disease by air pollution can thus facilitate viral infection in lower tracts (Shinya et al., 2006; van Riel et al., 2006).

In addition, various studies have reported a direct relationship between the spread and contagion capacity of some viruses with the atmospheric levels and mobility of air pollutants (Ciencewicki and Jaspers, 2007; Sedlmaier et al., 2009). The avian influenza virus (H5N1) could be transported across long distances by fine dust during Asian storms (Chen et al., 2010), and atmospheric levels of PM2.5, PM10, carbon monoxide, NO2 and sulphur dioxide were shown to influence the diffusion of the human respiratory syncytial virus in children (Ye et al., 2016), and the daily spread of the measles virus in China (Chen et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2020).

Although the capability of this coronavirus to bind particulate matters remains to be established, chronic exposure to atmospheric contamination and related diseases may represent a risk factor in determining the severity of Covid-19 syndrome and the high incidence of fatal events (Chen et al., 2020; Conticini et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a; Wu et al., 2020).

In conclusion, the actual pandemic event is demonstrating that infectious diseases represent one of the key challenges for human society. The periodic emergence of viral agents shows an increasing correlation with socio-economic, environmental and ecological factors (Morens et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2008). Our findings, if confirmed by future studies, suggest that air quality should also be considered as part of an integrated approach toward sustainable development, human health protection and prevention of epidemic spreads. However, the role of atmospheric pollution should be considered in a long-term, chronic perspective, and adoption of mitigation actions only during a viral outbreak could be of limited utility. We need to highlight that our analyses did not include other important determinants of Covid-19 incidence and mortality, such as age structure, lifestyle factors (e.g. diet or smoking habits), the prevalence of pre-existing conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory problems and diabetes prior to the pandemic, the capacity of the healthcare system, the case identification practices (e.g. the percentage of the population that were tested and the percentage of positive tests to the total number of tests), and the duration of the confinement, among others. Given these limitations, our findings should be interpreted as more hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. As such, we call for future studies to fill this gap of knowledge by addressing at which extent the aforementioned factors may have mutually contributed to the diffusion of Covid-19 in Italy.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors, Daniele Fattorini and Francesco Regoli, declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Payam Dadvand

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732.

Note

A complete description of the origin of the used data and the methods of graphic and statistical processing is included in the Supplementary Materials.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Brunekreef B., Holgate S.T. Air pollution and health. The Lancet. 2002;360(9341):1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda D., Tirani M., Rovida F., Demicheli V., Ajelli M., Poletti P., Trentin F., Guzzetta G., Marziano V., Barone A., Magoni M., Deandrea S., Diurno G., Lombardo M., Faccini M., Pan A., Bruno R., Pariani E., Grasselli G., Piatti A., Gramegna M., Baldanti F., Melegaro A., Merler S. 2020. The Early Phase of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy.https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2003/2003.09320.pdf Arxiv pre-print. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.-S., Tsai F.T., Lin C.K., Yang C.-Y., Chan C.-C., Young C.-Y., Lee C.-H. Ambient influenza and avian influenza virus during dust storm days and background days. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118(9):1211–1216. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Zhang W., Li S., Williams G., Liu C., Morgan G.G., Jaakkola J.J.K., Guo Y. Is short-term exposure to ambient fine particles associated with measles incidence in China? A multi-city study. Environ. Res. 2017;156:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciencewicki J., Jaspers I. Air pollution and respiratory viral infection. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19(14):1135–1146. doi: 10.1080/08958370701665434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Kupferschmidt K. Countries test tactics in “war” against COVID-19. Science. 2020;367(6484):1287–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.367.6484.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticini E., Frediani B., Caro D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environ. Pollut. 2020;114465 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F., Baker J.S., Navel V. COVID-19 as a factor influencing air pollution? Environ. Pollut. 2020;263:114466. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (European Union Agency) Situation update worldwide. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases as of 7 April 2020.

- EEA, European Environmental Agency . 2019. Air Quality in Europe. Report Number 10/2019. [Google Scholar]

- EEA, European Environmental Agency . 2020. Monitoring Covid-19 Impacts on Air Pollution.https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/air-quality-and-covid19/monitoring-covid-19-impacts-on Dashboard Prod-ID: DAS-217-en. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli D., Piazza F. Analysis and forecast of COVID-19 spreading in China, Italy and France. Chaos. Solitons & Fractals. 2020;134:109761. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda M.M., Shaikh S.B., Bhandary Y.P. Inflammatory and fibrinolytic system in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lung. 2018;196(5):609–616. doi: 10.1007/s00408-018-0150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhou L., Chen J., Chen K., Liu Y., Chen X., Tang F. Acute effects of air pollution on influenza-like illness in Nanjing, China: a population-based study. Chemosphere. 2016;147:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICPD, Italian Civil Protection Department . 2020. COVID-19 Monitoring.https://github.com/pcm-dpc/COVID-19 daily update (accessed 8 April 2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.E., Patel N.G., Levy M.A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J.L., Daszak P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampa M., Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2008;151(2):362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legambiente . Mal’Aria di città, Dossier 2018, 2019 and 2020. referring the European Environmental Agency; 2018. Annual dossier series on air quality in Italy. 2019 and 2020)(EEA) [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhin E., Holme J.A., Gualtieri M., Camatini M., Øvrevik J. Milan winter fine particulate matter (wPM2.5) induces IL-6 and IL-8 synthesis in human bronchial BEAS-2B cells, but specifically impairs IL-8 release. Toxicol. Vitro. 2018;52:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morens D.M., Folkers G.K., Fauci A.S. The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2004;430(6996):242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature02759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Zhao X., Tao Y., Mi S., Huang J., Zhang Q. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020. The effects of air pollution and meteorological factors on measles cases in Lanzhou, China. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret J., Bowatte G., Lodge C., Knibbs L., Gurrin L., Kandane-Rathnayake R., Johns D., Lowe A., Burgess J., Thompson B., Thomas P., Wood-Baker R., Morrison S., Giles G., Marks G., Markos J., Tang M., Abramson M., Walters E. The dose–response association between nitrogen dioxide exposure and serum interleukin-6 concentrations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(5):1015. doi: 10.3390/ijms18051015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? The Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmaier N., Hoppenheidt K., Krist H., Lehmann S., Lang H., Büttner M. Generation of avian influenza virus (AIV) contaminated fecal fine particulate matter (PM2.5): genome and infectivity detection and calculation of immission. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;139(1–2):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya K., Ebina M., Yamada S., Ono M., Kasai N., Kawaoka Y. Influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440(7083):435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riel D., Munster V.J., de Wit E., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Fouchier R.A.M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Kuiken T. H5N1 virus attachment to lower respiratory tract. Science. 2006;312(5772) doi: 10.1126/science.1125548. 399–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(11):1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Du Z., Zhu F., Cao Z., An Y., Gao Y., Jiang B. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):e52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts N., Amann M., Arnell N., Ayeb-Karlsson S., Belesova K., Boykoff M., Byass P., Cai W., Campbell-Lendrum D., Capstick S., Chambers J., Dalin C., Daly M., Dasandi N., Davies M., Drummond P., Dubrow R., Ebi K.L., Eckelman M. The 2019 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. The Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1836–1878. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32596-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Director . 2020. General’s Remarks at the Media Briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020 [Google Scholar]

- WHO Director . 2020. General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID19 on 11 March 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Gutierrez B., Mekaru S., Sewalk K., Goodwin L., Loskill A., Cohn E.L., Hswen Y., Hill S.C., Cobo M.M., Zarebski A.E., Li S., Wu C.-H., Hulland E., Morgan J.D., Wang L., O’Brien K., Scarpino S.V., Brownstein J.S. Epidemiological data from the COVID-19 outbreak, real-time case information. Scientific Data. 2020;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0448-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Fu J., Mao J., Shang S. Haze is a risk factor contributing to the rapid spread of respiratory syncytial virus in children. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2016;23(20):20178–20185. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Xie J., Huang F., Cao L. Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;727:138704. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.