Morphology assessment of COVID-19 pneumonia may be crucial for its diagnosis and management. Chest Computed Tomography (CT) scan has high diagnostic accuracy and may be associated with patient clinical condition [1]. However, during a pandemic the safe use of CT is questionable. Given its characteristics, CT scan cannot be considered as a screening tool (too wide target population) or a monitoring tool (intrahospital transfer, radiation, availability).

Lung ultrasound (LUS) has been validated for the diagnosis and the management of acute respiratory failure, pneumonia [2], even during viral pandemic [3]. LUS has high diagnostic accuracy for interstitial syndrome and alveolar consolidations, which are the most common radiological signs of COVID-19 pneumonia [4]. Moreover, preliminary reports are in favour of a predominant involvement of the pulmonary periphery, which could reinforce LUS interest in the actual pandemic.

Here, we described two cases of confirmed COVID-19 patients at early and late stages of the disease. We compared the CT scan and ultrasound features performed at the same time.

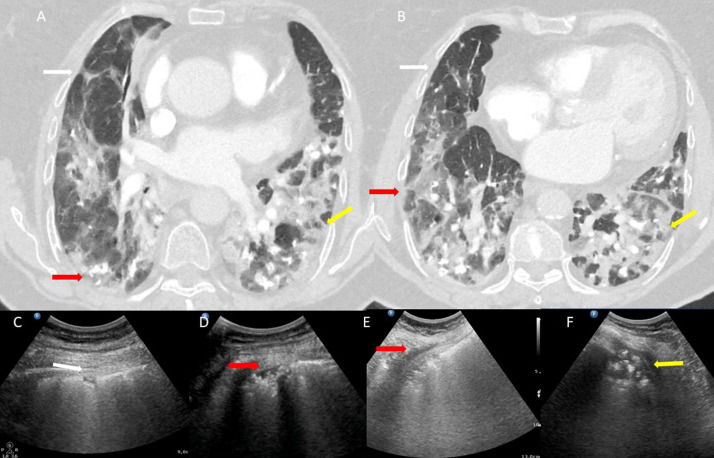

In a 70-year-old woman, at admission, CT scan showed the typical pattern of COVID-19 with peripheral ground-glass opacities that were bilateral and multilobar (Fig. 1 A and B). Ground-glass opacities appear as coalescent B-line areas and are associated with irregularities of pleural line (white arrows, Fig. 1A, 1B and C). This pattern alternates with normal area. Nodular or mass-like ground-glass opacities can also reach the periphery and be depicted as small consolidation in subpleural areas (red arrows, Fig. 1A, B, D and E) or consolidation (yellow arrows, Fig. 1A, B and E).

Fig. 1.

CT scan image and lung ultrasound patterns of patient n°1 with COVID-19 pneumonia in early stage.

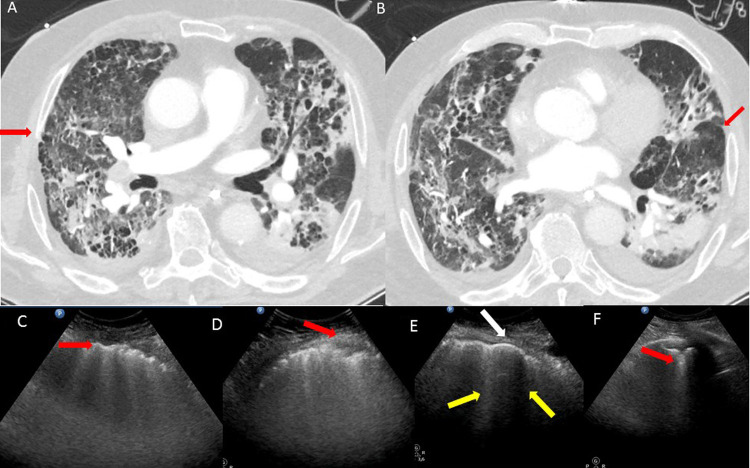

A 65-year-old male, after 25 days of mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome, developed on the CT scan fibrosis (Fig. 2 A and B) consisting of subpleural fibrosis, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis with anterior distribution and thickened interlobular septal [5]. These abnormalities using LUS were reported as irregularities of pleural line associated with coalescent B-lines (red arrows Fig. 2A, C and D) or multifocal subpleural consolidation (red arrows, Fig. 2C and D). Thickened interlobular septal seen as regularly spaced B-lines (yellow arrows Fig. 2E) combined with thickened pleural line allows the visualisation of secondary pulmonary lobules (white arrow; Fig. 2E). Thickened interlobular septal and small subpleural consolidations evidenced the major fissure (red arrows Fig. 2B and 2F).

Fig. 2.

CT scan image and lung ultrasound patterns of patient n°2 with COVID-19 pneumonia in late stage.

These two suggestive cases underline the potential of LUS for COVID-19 pneumonia assessment at different stages of the disease. Even if all LUS signs are not specific, the presence of these various patterns in a clinical context is very suggestive of viral pneumonia. Thus, LUS, when the clinical context is evocative, may help physicians to identify COVID-19 patients. After a proper validation of LUS against chest CT scan, one can believe that LUS could serve as a diagnostic and a triage tool detecting at risk patients, thus allowing a better allocation of ICU resources as previously described in another context [6]. Finally, it seems important to underline that LUS should also be associated with multi-organ point of care ultrasound. In particular, COVID-19 infection is associated with myocarditis and an elevated incidence of thromboembolic events. Thus, multi-organ point of care ultrasound could therefore be of high interest for the screening of these complications at the bedside with a minimum exposition of healthcare providers.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consents from the patients were waived, because of entirely anonymised images from which the individual cannot be identified.

Disclosure of interest

LZ received fees for teaching ultrasound to GE healthcare costumers.

References

- 1.Zhao W., Zhong Z., Xie X., Yu Q., Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a multicentre study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(5):1072–1077. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mojoli F., Bouhemad B., Mongodi S., Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):701–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0236CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Testa A., Soldati G., Copetti R., Giannuzzi R., Portale G., Gentiloni-Silveri N. Early recognition of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia by chest ultrasound. Crit Care. 2012;16(1):R30. doi: 10.1186/cc11201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J., Wu X., Zeng W., Guo D., Fang Z., Chen L. Chest CT findings in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 and its relationship with clinical features. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(5):257–261. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai S.R., Wells A.U., Rubens M.B., Evans T.W., Hansell D.M. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: CT abnormalities at long-term follow-up. Radiology. 1999;210(1):29–35. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.1.r99ja2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markarian T., Zieleskiewicz L., Perrin G., Claret P.G., Loundou A., Michelet P. A lung ultrasound score for early triage of elderly patients with acute dyspnea. CJEM. 2019;21(3):399–405. doi: 10.1017/cem.2018.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]