Abstract

Importance: Jail officers are an underserved population of public safety workers at high risk for developing chronic mental health conditions.

Objective: In response to national calls for the examination of stressors related to the unique work contexts of correctional facilities, we implemented a pilot study informed by the Total Worker Health® (TWH) strategy at two urban and two rural jails.

Design: Participatory teams guided areas of interest for a mixed-data needs assessment, including surveys with 320 jail officers to inform focus groups (N = 40).

Setting: Urban and rural jails in the midwestern United States.

Participants: Jail correctional officers and sheriff’s deputies employed at participating jails.

Measures: We measured mental health characteristics using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Mental Health scale, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, and the two-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist. Constructs to identify workplace characteristics included emotional support, work–family conflict, dangerousness, health climate, organizational operations, effectiveness of training, quality of supervision, and organizational fairness.

Results: On the basis of general population estimates, we found that jail officers were at higher risk for mental health disorders, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Jail officers identified workplace health interventions to address individual-, interpersonal-, institutional-, and community-level needs.

Conclusion: Implementation of a TWH needs assessment in urban and rural jails to identify evidence-informed, multilevel interventions was found to be feasible. Using this assessment, we identified specific workplace health protection and promotion solutions.

What This Article Adds: Results from this study support the profession’s vision to influence policies, environments, and systems through collaborative work. This TWH study has implications for practice and research by addressing mental health needs among jail officers and by providing practical applications to create evidence-informed, tailored interventions to promote workplace health in rural and urban jails.

Nearly 40% of U.S. public safety employees are jail-based officers, a subset of correctional officers (COs; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). These officers serve in 3,280 jail facilities through which an estimated 11 million incarcerated people cycle each year (Minton & Zeng, 2016; Stephan & Walsh, 2011). Employment within prison settings has been associated with high rates of stress. Prison officers have been the source of most correctional workplace health research, and they have demonstrated higher rates of sick leave, absenteeism, and short tenure compared with other work sectors; ultimately, they have reported high job dissatisfaction (Brower, 2013). COs have also experienced higher rates of mental illness: their rate of depression (31%) is more than triple that of the general population (9%; Obidoa et al., 2011; Vilagut et al., 2016). They have also been found to be at higher risk for suicidal ideation (Stack & Tsoudis, 1997).

Correctional facilities vary in size, resources, population of residents, length of stay, and level of security. Jails function as short-term, pretrial facilities and hold people before their court sentencing or who have terms of less than 1 yr, and they are typically understaffed, overcrowded, and underfunded to provide specialized services (Lurigio, 2015). An examination of jail workplace health is needed to inform interventions.

In a review of prison officer wellness and safety literature, Brower (2013) described four categories of stressors: resident (inmate) related, work environment, organizational and administrative, and psychosocial. These categories were further supported by Ferdik and Smith (2017). Mental health resources for COs are typically limited to underutilized employee assistance programs (McRee, 2017) and educational materials describing the signs and symptoms of mental health disorders such as depression, exposing a large gap in workplace resources and supports for addressing officer health needs.

Strategies for health promotion in various sizes of workplace have been established (Rohlman et al., 2018). Smaller workplaces (i.e., <50–999 employees) typically have different organizational structures, fewer resources, and less expertise and capacity to commit to workplace health and safety programs than do larger workplaces (Dale et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2017). Participatory interventions to address job stressors that may contribute to mental health disorders have been less emphasized (Nobrega et al., 2017).

Health promotion and protection frameworks, such as the Total Worker Health® (TWH) approach (Schill, 2017), offer strategies for addressing workplace stressors, conditions, policies, and practices through integrated, multilevel collaboration (Baron et al., 2014; Sorensen et al., 2016). Having evolved from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s Steps to a Healthier U.S. Workforce program (Sorensen & Barbeau, 2012), TWH is an emerging paradigm for prioritizing work environment changes (including physical, organizational, and psychosocial factors) and moving away from the onus for risk mitigation placed primarily on the individual worker (Tamers et al., 2018; Weisfeld & Lustig, 2014).

An evidence-based needs assessment method supported by TWH is community-based participatory research (CBPR). The CBPR method has been applied in work settings (Bradley-Bull et al., 2009) because of its collaborative process for engaging partners to inform changes in community health, management systems, and programs or policies (Wilson, 2018). An ongoing TWH project since 2006 has shown strong research and collaboration with prison organizations; however, challenges to engaging partners throughout the participatory process have occurred (Dugan et al., 2016). Research informed by TWH and application of CBPR with U.S. city and county jails have been underutilized.

In response to national calls for the examination of stressors related to the unique work contexts of jail officers (National Occupational Research Agenda Public Safety Sector Council, 2013), we sought to investigate the mental health needs of officers in a pilot study at three jails. Informed by the social–ecological framework used to delineate multilevel (person, interpersonal, management, and institution) factors (Stokols, 1996), our study had the following aims: (1) describe the characteristics of participating jails and feasibility of implementing CBPR using mixed-data needs assessment, (2) determine workplace health needs through the exploration of current mental health in this jail officer sample compared with the general population, and (3) identify examples of workplace health and safety interventions to potentially reduce job stressors and improve workplace mental health. This study contributes evidence-informed methods and descriptors of health needs to reduce the gap in the literature regarding TWH interventions in urban and rural jails.

Method

Program Details

In partnership with the Saint Louis University (SLU) Health Criminology Research Consortium, the SLU Transformative Justice Initiative seeks to develop evidence-informed solutions to improve health promotion and protection in criminal justice system settings. One urban Division of Corrections (DOC; 2 jail sites; 352 officers, averaging 1,400 residents) and 2 rural jails (49 officers, averaging 100 residents) in the midwestern United States were recruited for this project.

Research Design

We used defining elements of TWH, including (1) identification of leadership commitment to worker safety and health at multiple organizational levels and (2) promotion and support of worker engagement through identification of safety and health issues and related solutions (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], 2016). We applied this TWH approach with CBPR methods in a multilocation, cross-sectional study using an emergent mixed quantitative and qualitative needs assessment. This study was approved by the SLU institutional review board (IRB).

Study Procedures

In 2015, purposive sampling of jails occurred within a 60-mile radius (1-hr drive) of the university location. We contacted seven facilities: four rural jails and three urban DOC and county sheriff’s departments. Two rural jails (1 jail site each) and one urban DOC (2 jail sites) employing a total of 401 officers were selected. Eligible participants were at least age 18 yr and employed as a CO or jail-based sheriff’s deputy (collectively referred to as officers for the purposes of this study) at the participating facility. During shift start-up meetings at each facility between October and November 2015, researchers informed officers about the study and invited them to participate in accordance with IRB procedures. Officers who provided informed consent and filled out the paper-based survey received a $20 gift card for their participation.

Focus groups and interviews occurred in May 2016 at four jail sites. We recruited participants at each jail, including new officers (employed for ≤2 yr), veteran officers employed for more than 5 yr, and upper ranks of officers. Higher ranking officers were interviewed separately at the urban jail. Interview duration was approximately 30 min, and focus groups were 45 min each. Officers received a $30 gift card for their participation.

Needs Assessment Using Community-Based Participatory Research

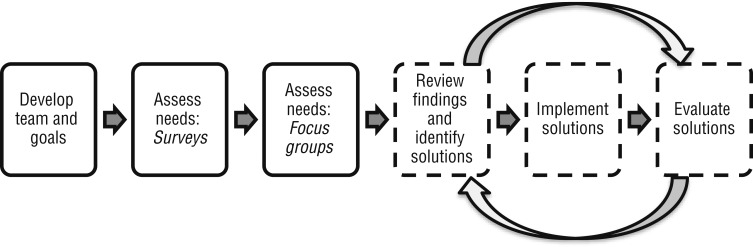

We developed a simplified workplace health needs assessment from existing TWH tools (Nobrega et al., 2017). Our needs assessment flow diagram is provided in Figure 1. To develop the needs assessment, researchers first facilitated identification and selection of CBPR team members at each jail and held a series of team meetings during late 2015 through 2016. Team members represented different ranks of officers in both rural and urban sites, and the urban team also included a representative from the city’s department of safety.

Figure 1.

Total Worker Health® participatory needs assessment and intervention process.

Note. Dotted lines and curved arrows indicate a continuous process for future evaluation of solution implementation.

In CBPR team meetings, we identified categories of interest, including workplace culture, communication, training, safety, health, policy, and community. Teams then identified relevant survey items from lists of existing TWH instruments compiled by the researchers and reviewed the survey items before approving them for use. Summaries of survey results were presented to the teams to develop future focus group and interview questions of interest. The goal of these questions was to identify officer workplace health concerns and related suggestions for workplace improvements. Summarized focus group results were presented to the teams for identification of potential solutions related to the identified workplace health needs.

Jail Participation and Feasibility

We used process evaluation metrics to describe the extent to which needs assessment activities occurred. These metrics included meeting occurrence and attendance, survey and focus group participation, and involvement of each jail in intervention planning.

Quantitative Measures

Demographic characteristics and general mental health issues among jail officers were identified through the following constructs: age, years employed, gender, ethnicity, job category, education level completed, military service, relationship status, and responsibility for children. We measured mental health characteristics using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Mental Health scale (HealthMeasures, 2018), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (Radloff, 1977), and the two-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist (PCL–2; Lang et al., 2012), which are described in detail in separate studies (Jaegers, Matthieu, Vaughn, et al., 2019; Jaegers, Matthieu, Werth, et al., 2019).

We used the social–ecological framework to guide constructs of interest for identifying workplace health concerns and to inform the development of focus group questions. Constructs and their internal consistency included person-level self-efficacy (α = .85; Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) and job satisfaction (one item; Hurrell & McLaney, 1988), as well as interpersonal-level emotional support (α = .91; HealthMeasures, 2018), work–family conflict (α = .73; Frone et al., 1992), and PROMIS mental health (α = .75). Constructs representing perceptions of the workplace included dangerousness (α = .83; Cullen et al., 1983), health climate (α = .75; Zweber et al., 2016), organizational operations (α = .79), effectiveness of training (α = .69), quality of supervision (α = .62), and organizational fairness (α = .58; Saylor et al., 1996), with some items modified from the original to reflect jail operations.

Qualitative Measures

Survey results were used to guide modifications to an existing resource for facilitating workplace focus groups: the TWH Focus Group Guide for Workplace Health and Safety (Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace, 2015). The focus group script included community and policy influence on work, institution and interpersonal aspects of the workplace, job stress, health and wellness suggestions, and ideas for workplace solutions.

Data Analysis

For this mixed-data study, descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the sample’s demographics and prevalence of health issues. We stratified by rural and urban jail facilities to further describe the subsample demographics and health descriptors. Qualitative data were transcribed and analyzed in AtlasTi (Version WIN 7.5, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A codebook developed by researcher-generated provisional coding (i.e., starting list of codes) was followed by in vivo coding (i.e., participant’s own language) and descriptive codes (i.e., summary of passage topics; Miles et al., 2014). Transcribed data were independently coded by two raters, and ties were broken by a third rater. Triangulation methods were used by comparing and relating survey results to focus group findings to determine an overall interpretation of these data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2006).

Results

Aim 1: Implementation Feasibility

Three correctional departments, including four jail sites, participated in the CBPR process and needs assessment. Characteristics of each participating jail facility are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Rural and Urban Jails (N = 4) That Participated in a Workplace Health Needs Assessment

| Jail Characteristic | County Sheriff’s Department | City Division of Corrections | ||

| Rural 1 | Rural 2 | Urban 1 | Urban 2 | |

| No. of COs (N = 401) | 18 | 31 | 156 | 196 |

| Jail residents | 110 over capacity | 110 over capacity | 1,800; capacity is 2,000 | |

| Participatory team membersa | 2 | 3 | 12 | |

| Participatory meetings | 5 | 4 | 6 | |

| Survey participants (N = 320) | 18 | 30 | 102 | 170 |

| FG or I (N = 40) | 2 (I) | 2 (I) | 15 (both I and FG) | 21 (both I and FG) |

| Jail style | Indirect supervision pods | Linear cells | Dormitory and direct supervision pods | Direct and indirect supervision pods |

| Type of daily shifts | 2 12-hr shifts | 2 12-hr shifts | 3 8-hr shifts | 3 8-hr shifts |

| Shift assignment | Rotate every 14 days | Rotate every 28 days | Bid on shift | Bid on shift |

| Preshift briefings | 15-min “pass on” | Shift change meeting | 30-min briefing | 30-min briefing |

| Training | On the job | Police academy, on the job | 6-wk training academy | 6-wk training academy |

Note. Bid on shift = employees enter their name into a lottery and bid on the shift that they prefer; COs = correctional officers; FG = focus group; I = interview.

Does not include researchers.

Meetings occurred with each department (two county sheriff’s jails and one city DOC serving two jails), survey return rate was high (80%), and focus groups and interviews occurred as planned. Workplace health intervention planning informed by the results of this study was continued with CBPR teams at urban jails and was less consistent among the rural jails.

Aim 2: Workplace Mental Health

Demographic and mental health characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. The median age was 44 yr, and 52% of officers were female. Officers scored an average of 47, 3 points below the U.S. average (T = 50, standard deviation = 10), on the PROMIS Global Mental Health scale, indicating lower mental health among officers than the general population. Of the officers, 53.4% identified PTSD symptoms using the PCL–2. Workplace health constructs are listed in Table 3. Most officers indicated that employees and management did not work together as a team (73.8%) and that officers were unable to express their views and feelings about changes in policies and procedures (72.5%).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Rural and Urban Jail Officers

| Characteristic | Total (N = 320), n (%)a | Rural (n = 48), na | Urban (n = 272), na |

| Age (M, SD) | 43.33 (11.40) | 36.15 (12.71) | 44.62 (10.66) |

| Years employed (M, SD) | 9.84 (7.51) | 7.19 (7.51) | 10.30 (7.42) |

| Genderb | |||

| Female | 166 (52.37) | 13 | 153 |

| Male | 151 (47.63) | 35 | 116 |

| Ethnicityb | |||

| African American, Black, or other | 251 (78.43) | 2 | 248 |

| European descent, Caucasian, or White | 69 (21.56) | 45 | 24 |

| Job category | |||

| Jail deputy (rural) or correctional officer (urban) | 253 (79.06) | 34 | 219 |

| Supervisor, corporal, manager (rural), or lieutenant or captain (urban) | 63 (19.69) | 14 | 49 |

| Unspecified | 4 (1.25) | 0 | 4 |

| Educationb | |||

| High school | 69 (21.63) | 16 | 53 |

| Some college | 133 (41.69) | 20 | 113 |

| College degree | 117 (36.68) | 12 | 105 |

| Military service | 50 (15.63) | 13 | 37 |

| Primary or shared responsibility for children | 184 (57.50) | 30 | 154 |

| Partnered relationship status | 164 (51.25) | 32 | 132 |

| Mental health characteristics | |||

| PROMIS mental health score <50 (less healthy) | 212 (66.25) | 32 | 180 |

| Depression, CES–D–10 | 100 (31.25) | 13 | 87 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder, PCL–2 | 171 (53.44) | 25 | 146 |

Note. CES–D–10 = 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; M = mean; PCL–2 = two-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SD = standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Due to missing responses, some items do not total 100%.

Table 3.

Workplace Health Constructs to Inform the Jail-Based TWH Needs Assessment

| Construct | M (SD) | ||

| Total | Rural | Urban | |

| Job satisfactiona | 2.57 (0.89) | 3.02 (0.84) | 2.49 (0.88) |

| Self-efficacya | 3.32 (0.40) | 3.34 (0.35) | 3.32 (0.41) |

| Emotional support (PROMIS)b | 3.96 (1.01) | 4.03 (0.96) | 3.95 (1.03) |

| Dangerousnessb | 4.44 (0.73) | 4.18 (0.72) | 4.49 (0.73) |

| Work–family conflictb | |||

| Demands of home life interfere with job | 1.93 (0.87) | 2.22 (0.80) | 1.88 (0.87) |

| Demands of job interfere with family life | 2.51 (0.95) | 2.83 (0.94) | 2.45 (0.94) |

| Balancing paid work and your family life (how successful) | 3.33 (0.88) | 3.33 (0.93) | 3.33 (0.87) |

| Health climatec | |||

| If my health were to decline, my coworkers would take steps to support my recovery. | 3.36 (1.56) | 4.51 (1.20) | 3.16 (1.53) |

| My supervisor encourages participation in organizational programs that promote employee health and well-being. | 2.61 (1.52) | 3.19 (1.41) | 2.51 (1.52) |

| In my work group, use of sick days for illness or mental health issues is supported and encouraged. | 2.60 (1.54) | 3.44 (1.46) | 2.45 (1.51) |

| My organization provides me with opportunities and resources to be healthy. | 2.90 (1.54) | 3.48 (1.60) | 2.80 (1.51) |

| My organization encourages me to speak up about issues and priorities regarding employee health and well-being. | 2.62 (1.51) | 3.19 (1.45) | 2.52 (1.51) |

| Organizational operationsc | |||

| Information that I get from formal communication channels helps me to perform my job effectively. | 3.45 (1.47) | 4.04 (1.17) | 3.35 (1.50) |

| In general, this institution is run very well. | 2.58 (1.49) | 3.94 (1.08) | 2.33 (1.42) |

| Management at this institution is flexible enough to make changes when necessary. | 2.71 (1.58) | 3.92 (1.44) | 2.50 (1.51) |

| It’s really not possible to change things in this institution. | 3.54 (1.73) | 3.38 (1.59) | 3.57 (1.75) |

| I have the authority I need to accomplish my work objectives. | 3.39 (1.62) | 4.43 (1.21) | 3.12 (1.61) |

| Employees and management work together as a team. | 2.35 (1.43) | 3.56 (1.50) | 2.13 (1.30) |

| Coworkers and I work together as a team. | 3.95 (1.42) | 4.96 (1.03) | 3.77 (1.40) |

| Effectiveness of trainingc | |||

| This jail’s training program does not prepare me or help me deal with situations that arise on the job. | 3.54 (1.60) | 3.09 (1.49) | 3.63 (1.61) |

| My jail training has helped me to work effectively with inmates. | 3.73 (1.50) | 4.26 (1.31) | 3.64 (1.51) |

| I receive the kind of training that I need to perform my job well. | 3.43 (1.58) | 4.04 (1.47) | 3.32 (1.57) |

| Quality of supervisionc | |||

| My supervisor asks my opinion when a work-related problem arises. | 3.24 (1.65) | 4.06 (1.42) | 3.10 (1.65) |

| I have a great deal of say over what has to be done on my job. | 2.68 (1.56) | 3.53 (1.35) | 2.53 (1.55) |

| The standards used to evaluate my performance have been fair and objective. | 3.71 (1.47) | 4.06 (1.24) | 3.65 (1.50) |

| Organizational fairnessc | |||

| Changes in policies and procedures were applied consistently throughout the jail. | 3.18 (1.67) | 3.57 (1.39) | 3.11 (1.70) |

| I was able to express my views and feelings about changes in policies and procedures at the jail. | 2.44 (1.47) | 3.60 (1.36) | 2.24 (1.40) |

Note. M = mean; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SD = standard deviation; TWH = Total Worker Health.

Agreement scales: 1 = low, 4 = high.

Agreement scales: 1 = low, 5 = high.

Agreement scales: 1 = low, 6 = high.

Six interviews (four rural, two urban) and eight focus groups were held at urban jail locations. Forty participants were involved in either an interview or a focus group; of those, 8 officers represented upper levels of rank. Identification of workplace problems and related health intervention solutions are presented in Table 4. Themes included impact on the individual (intrapersonal), coworkers and jail residents (interpersonal), communication and respect (institutional), training and internal procedures (institutional), public perception (community), and overcrowding and residency (policy). Survey data were supported through triangulation in focus group and interview discussions in which officers expressed frustration with and concern over not feeling respected by coworkers, supervisors, residents, and the community. All groups expressed the need for self-defense and mental health training beyond the scope of new hire general training. For the rural jails, training was designed for police officers working in the community; it was not designed for those officers doing internal jail work. Low manpower and staff support were major concerns paired with overcrowding in facilities not designed for the high number of residents. Officers described a variety of job stressors, including pressure from supervisors, workplace policies, and negative public perceptions.

Table 4.

Multilevel Qualitative Themes Identified in Jail Officer Focus Groups

| Level | Problem Themes | Rural (R) and Urban (U) Quotes | Identified Solutions |

| Intrapersonal | Impact on the individual, role identity |

|

|

| Interpersonal | Coworkers, residents |

|

|

| Institution: Management | Communication consistency, appreciation and respect of officers, use of consequences |

|

|

| Institution: Operations | Training, staffing, breaks, internal policies, environment |

|

|

| Community (public safety, general public) | Public perception of the jail and officers |

|

|

| Policy (city and county) | Jail overcrowding, residency |

|

• Collaborate with city and county representatives to address larger issues around incarceration, local policies, and equitable treatment across public safety workers |

Note. EAP = employee assistance program.

Aim 3: Identification of Workplace Health and Safety Interventions

With evidence from our needs assessment, we worked with CBPR teams at each jail to identify potential workplace interventions. We organized the types of health interventions into the following categories: workplace culture and communication (e.g., appreciation, treatment by coworkers and management, accountability, and respect), training and safety (e.g., staffing support, annual follow-up, new training topics such as self-defense, behavioral and mental health, and safety equipment), and community (e.g., working with community-based health resources and the public’s perception of CO work). The urban team most strongly expressed that respect and appreciation among coworkers and with all levels of management were needed to reduce job stress and to improve their job satisfaction. The rural jail officers were most concerned with job support, improving staffing, and reducing overcrowding. Officers from both types of jails expressed concerns with their inability to take breaks, inconsistent practices between work shifts, and the need for more training specific to jail work.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the mental health needs of jail officers at three jail departments to inform the identification of health promotion interventions using a TWH approach. We determined that implementation of a participatory team process and mixed-data needs assessment was feasible to complete in rural and urban jails. In addition, we identified the high-level need for jail workplace health interventions to improve the mental health of jail officers. Rural and urban jails displayed similarities in their mental health and workplace concerns, but officers at each jail also expressed differences unique to their workplaces. Traditionally, workplace health and safety programs have focused on safety protections specific to the work itself, rather than the influence of workplace policies, practices, and programs on health (NIOSH, 2016). Issues relevant to TWH were naturally identified in this study, including control of psychosocial factors within hazards and exposures, organization of work, leadership, community supports, workforce demographics, and policy issues.

We found that officers had poorer mental health and higher rates of depression and PTSD than workers in the general population. Of the officers, 31% reported depressive symptoms, compared with an estimated 9% for the general population (Vilagut et al., 2016), and 53.4% screened positive for PTSD symptoms, nearly 7 times the rate of the general population (8.2%; Kessler et al., 2005). Surprisingly, 52% of our sample was female, more than double the national rate (24%) of women classified as bailiffs, COs, and jailers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017), indicating the potential need to identify tailored interventions for female officers.

We found that with small- and medium-sized facilities having limited management and administrative layers, a simple needs assessment process was appropriate for this project. The straightforward process of discussion, data collection, and transparency in reporting to the participatory teams kept the team involved and engaged in the year-long process. Officers appeared to be trusting of the researchers and expressed appreciation for having the opportunity to voice their concerns. However, only the urban jail officers continued to participate after the needs assessment concluded and the implementation phase began. The urban jail officers, with more resources, active top-level support, and a larger team, created their own identity (“Better Tomorrow in Corrections [B2C]”), and their intervention work continues. However, the rural sites continued to experience low staffing, overtime, and overcrowding, potentially limiting their ability to fully participate in the intervention phase of the project.

Officers expressed the need for additional training in jail mental health and noninvasive defensive tactics to prevent the need for use of force. They identified the need for low-cost, efficient methods for rural officer training where in-house training academies do not exist. Pooling rural county training resources had been attempted, but the network and commitment were not strong enough to sustain it. Police officer research has shown that mental health training has improved communication and willingness to work with people experiencing mental illness (Hansson & Markström, 2014). A study by Steiner and Wooldredge (2015) suggested that stress reduction is related to perceived control over prison residents and coworker support. Empowering jail officers with practical skills and providing them with lived experience through applied training and a proactive approach may increase their ability to improve interactions within the jail setting and perceived job control. Creating a correctional culture that builds on officer talents and the needs of jail residents is encouraged for more holistic, humane, health-promoting, and rehabilitative services (Ahalt et al., 2020).

Study Strengths and Limitations

This is the first known TWH study implemented among jail-based officers. We used robust methods, including CBPR and data collection from mixed sources, to identify workplace health needs. This project contributes to research on the occupational health of jail officers, an understudied public safety workforce. Because of the small sample size and cross-sectional design, no causal results can be inferred, and we were unable to generalize our findings to other workplaces. Our results may be influenced differently from national samples because of the large representation of female officers (28% more than the national rate). Although each jail site appeared to be unique, we were not able to analytically compare rural and urban findings because of lack of statistical power given the small rural sample size.

Although the needs assessment was adequate, a missing piece could be the lack of thorough job analyses during data collection. Occupational health research and interventions are often informed by analyses of job tasks and work demands. Officers described how they felt a lack of freedom because of being “locked up” during the workday. Occupational deprivation is an underlying theme of the officer work role, in which restrictive procedures limit creativity and decision making, which in turn can lead to job burnout. Both rural and urban officers described their role as a “glorified babysitter or butler” by serving meals and issuing clothing and other necessities, and they suggested more activities and daily routines to give residents something to do. A comprehensive job analysis could provide better insight into meaningful roles for officers, response to emergency situations, critical incidents, work demands and flow, and types of stressors and exposure to those stressors.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

Results from this study support the profession’s vision to influence policies, environments, and systems through collaborative work (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2017). In addition, the results have the following implications for occupational therapy practice to address mental health needs among jail officers:

Practitioners can implement practical applications of CBPR assessment for evidence-informed, tailored workplace interventions in rural and urban jails using the TWH strategy to reduce workplace stressors.

Practitioners can evaluate the implementation of multilevel interventions and workplace health and safety outcomes to determine the effectiveness of occupation-based TWH interventions that address routines, roles, contexts, and environment.

Conclusion

With a community-based, participatory approach guided by the TWH paradigm, it was feasible to implement a multilevel needs assessment to identify jail workplace characteristics that inform health promotion and protection interventions. Parsing these data to describe unique characteristics of rural and urban jails and how to tailor interventions based on their needs is critical. In future studies, researchers using CBPR methods may reveal unique worker characteristics and workplace stressors for evidence-informed occupational therapy interventions to address workplace health.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation and thanks to the officers, deputies, management, and staff at participating jails, including the City of St. Louis Division of Corrections, for their engagement in this study. We also thank Patrick Kelly and Paul Werth for data support. This research was supported in part by a pilot project grant from the Healthier Workforce Center (HWC) at the University of Iowa. The HWC is supported by Cooperative Agreement U19OH008868 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC, NIOSH, HWC, or participating jails.

Contributor Information

Lisa A. Jaegers, Lisa A. Jaegers, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Doisy College of Health Sciences, and School of Social Work, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO; lisa.jaegers@health.slu.edu

Syed Omar Ahmad, Syed Omar Ahmad, PhD, OTD, is Professor, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Doisy College of Health Sciences, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Gregory Scheetz, Gregory Scheetz, MSW, LCSW, is Clinical Social Worker, UCLA Health, Los Angeles. At the time of the study, he was Student, School of Social Work, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Emily Bixler, Emily Bixler, MPH, CPH, ATC, is Research Associate, National Safety Council, Itasca, IL. At the time of the study, she was Student, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health and Department of Biosecurity, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Saketh Nadimpalli, Saketh Nadimpalli, MPH, is Regulatory Affairs Manager, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. At the time of the study, he was Student, Department of Epidemiology, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Ellen Barnidge, Ellen Barnidge, PhD, MPH, is Associate Professor, Department of Behavioral Science and Health Education, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Ian M. Katz, Ian M. Katz, MS, is Doctoral Student, Department of Psychology, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO.

Michael G. Vaughn, Michael G. Vaughn, PhD, is Professor, School of Social Work, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO

Monica M. Matthieu, Monica M. Matthieu, PhD, LCSW, is Associate Professor, School of Social Work, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO

References

- Ahalt C., Haney C., Ekhaugen K., & Williams B. (2020). Role of a US–Norway exchange in placing health and well-being at the center of US prison reform. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (Suppl. 1), S27–S29. 10.2105/ajph.2019.305444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2017). Vision 2025. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 7103420010 10.5014/ajot.2017.713002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. L., Beard S., Davis L. K., Delp L., Forst L., Kidd-Taylor A., . . . Welch L. S. (2014). Promoting integrated approaches to reducing health inequities among low-income workers: Applying a social ecological framework. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 57, 539–556. 10.1002/ajim.22174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley-Bull K., McQuiston T. H., Lippin T. M., Anderson L. G., Beach M. J., Frederick J., & Seymour T. A. (2009). The union RAP: Industry-wide research-action projects to win health and safety improvements. American Journal of Public Health, 99(Suppl. 3), S490–S494. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.148544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower J. (2013). Correctional officer wellness and safety literature review (Accession No. 028104). Retrieved from https://nicic.gov/correctional-officer-wellness-and-safety-literature-review

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). Women in the labor force: A databook (Report No. 1065). BLS Reports. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/2016/pdf/home.pdf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Occupational employment and wages: 33-3012: Correctional officers and jailers. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes333012.htm#nat

- Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace. (2015). Focus group guide for workplace health and safety. Retrieved from https://www.uml.edu/docs/Focus_Group_Guide_ProjD_revised2-19-15_tcm18-167587.pdf

- Creswell J. W., & Plano Clark V. L. (2006). Choosing a mixed methods design. In Creswell J. W. & Plano Clark V. L. (Eds.), Designing and conducting mixed methods research (pp. 62–79). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen F. T., Link B. G., Travis L. F. III, & Lemming T. (1983). Paradox in policing: A note on perceptions of danger. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 11, 457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Dale A. M., Jaegers L., Welch L., Gardner B. T., Buchholz B., Weaver N., & Evanoff B. A. (2016). Evaluation of a participatory ergonomics intervention in small commercial construction firms. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 59, 465–475. 10.1002/ajim.22586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan A. G., Farr D. A., Namazi S., Henning R. A., Wallace K. N., El Ghaziri M., . . . Cherniack M. G. (2016). Process evaluation of two participatory approaches: Implementing Total Worker Health® interventions in a correctional workforce. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 59, 897–918. 10.1002/ajim.22593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdik F. V., & Smith H. P. (2017). Correctional officer safety and wellness: Literature synthesis. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/250484.pdf

- Frone M. R., Russell M., & Cooper M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict: Testing a model of the work–family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78. 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson L., & Markström U. (2014). The effectiveness of an anti-stigma intervention in a basic police officer training programme: A controlled study. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 55 10.1186/1471-244X-14-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthMeasures (2018). PROMIS: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurementsystems/promis/obtain-administer-measures [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell J. J. Jr., & McLaney M. A. (1988). Exposure to job stress—A new psychometric instrument. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 14(Suppl. 1), 27–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegers L. A., Matthieu M. M., Vaughn M. G., Werth P., Katz I. M., & Ahmad S. O. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder and job burnout among jail officers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61, 505–510. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegers L. A., Matthieu M. M., Werth P., Ahmad S. O., Barnidge E., & Vaughn M. G. (2019). Stressed out: Predictors of depression among jail officers and deputies. Prison Journal, 100, 240–261. 10.1177/0032885519894658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K. R., & Walters E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J., Cluff L., Rineer J., Brown D., & Jones-Jack N. (2017). Building capacity for workplace health promotion: Findings from the Work@Health® train-the-trainer program. Health Promotion Practice, 18, 902–911. 10.1177/1524839917715053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. J., Wilkins K., Roy-Byrne P. P., Golinelli D., Chavira D., Sherbourne C., . . . Stein M. B. (2012). Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34, 332–338. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurigio A. J. (2015). Jails in the United States: The “old-new” frontier in American corrections. Prison Journal, 96, 3–9. 10.1177/0032885515605462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McRee J. (2017). How perceptions of mental illness impact EAP utilization. Benefits Quarterly, 33, 37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., & Saldana J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Minton T. D., & Zeng Z. (2016). Jail inmates in 2015 (NCJ 250394). Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji15.pdf

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2016). Fundamentals of Total Worker Health approaches: Essential elements for advancing worker safety, health, and well-being (Pub. No. 2017-112). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- National Occupational Research Agenda Public Safety Sector Council. (2013). National public safety agenda for occupational safety and health research and practice in the U.S. public safety sector. Atlanta: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega S., Kernan L., Plaku-Alakbarova B., Robertson M., Warren N., & Henning R.; CPH-NEW Research Team. (2017). Field tests of a participatory ergonomics toolkit for Total Worker Health. Applied Ergonomics, 60, 366–379. 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obidoa C., Reeves D., Warren N., Reisine S., & Cherniack M. (2011). Depression and work family conflict among corrections officers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53, 1294–1301. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182307888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlman R., Campo S., Hall J., Robinson E. L., & Kelly K. M. (2018). What could Total Worker Health® look like in small enterprises? Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 13(Suppl. 1), S34–S41. 10.1093/annweh/wxy008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor W., Gillman E. B., & Camp S. D. (1996). Prison and Social Climate Survey: Reliability and validity analyses of the work environment constructs. Retrieved from https://www.bop.gov/resources/research_projects/published_reports/cond_envir/oresaylor_pscsrv.pdf

- Schill A. L. (2017). Advancing well-being through Total Worker Health®. Workplace Health and Safety, 65, 158–163. 10.1177/2165079917701140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., & Jerusalem M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In Weinman J., Wright S., & Johnston M. (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio (pp. 35–37). Windsor, England: NFER-Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G., & Barbeau E. (2012). Research compendium: The NIOSH Total Worker Health™ Program: Seminal research papers 2012 (DHHS [NIOSH] Pub. No. 2012-146). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- Sorensen G., McLellan D. L., Sabbath E. L., Dennerlein J. T., Nagler E. M., Hurtado D. A., . . . Wagner G. R. (2016). Integrating worksite health protection and health promotion: A conceptual model for intervention and research. Preventive Medicine, 91, 188–196. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. J., & Tsoudis O. (1997). Suicide risk among correctional officers: A logistic regression analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 3, 183–186. 10.1080/13811119708258270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B., & Wooldredge J. (2015). Individual and environmental sources of work stress among prison officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42, 800–818. 10.1177/0093854814564463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan J., & Walsh G. (2011). Census of jail facilities, 2006 (NCJ 230188). Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cjf06.pdf

- Stokols D. (1996). Translating Social Ecological Theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10, 282–298. 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamers S. L., Goetzel R., Kelly K., Luckhaupt S., Nigam J., Pronk N. P., . . . Sorensen G. (2018). Research methodologies for Total Worker Health®: Proceedings from a workshop. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, 968–978. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut G., Forero C. G., Barbaglia G., & Alonso J. (2016). Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES–D): A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11, e0155431 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisfeld V., & Lustig T. A. (2014). Promising and best practices in Total Worker HealthTM: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. (2018). Community-based participatory action research. In Liamputtong P. (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 1–15). Singapore: Springer; 10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_87-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zweber Z., Henning R. A., & Magley V. J. (2016). A practical scale for multi-faceted organizational health climate assessment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21, 250–259. 10.1037/a0039895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]