Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of six-weeks of resistance training with different volume load on the maximum glycolysis rate. 24 male strength-trained volunteers were assigned in a high volume low load (50% of their 1RM with 5 sets and reps up to muscle failure) and a low volume high load (70% of their 1RM with 5 sets of ten reps) resistance exercise group. The resistance training performed 3 days per week over 6 weeks. The maximum glycolysis rate was determined using isokinetic force testing before and after the intervention. There was a significant increase in glycolysis rate over the training period across all subjects (p=0.032). High volume low load exercise increased significantly from 0.271±0.067 mmol·l −1 ·s −1 to 0.298±0.067 mmol·l −1 ·s −1 (p=0.022) and low volume high load exercise showed no significant changes from 0.249±0.122 mmol·l −1 ·s −1 to 0.291±0.089 mmol·l −1 ·s −1 (p=0.233). No significant effect on glycolysis rate was observed between the training groups (p=0.650). Resistance training increases glycolysis rate regardless of volume load.

Key words: resistance exercise, lactate, anaerobic power, anaerobic metabolism, muscle adaption

Introduction

Resistance training represents a great strain for anaerobic energy metabolism. This metabolic strain is an important prerequisite for muscle growth and adaption of energy metabolism 1 . In various studies, high-energy substrates, such as creatine phosphate (PCr) and adenylic acids (ATP, ADP), were examined during strength exertion or strength training and significant changes in concentration were observed during and immediately after exertion 2 3 . Other studies show the high burden on anaerobic energy metabolism using lactate concentration [La+], which is mostly considered post-load 4 5 6 7 .

In the long term, regular strength training leads to the adaption of enzymes and substrates of energy supply and muscle volume 7 8 9 10 11 . It has been shown, for example, that the activity of anaerobic metabolism enzymes (lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), myokinase) in glycolytic muscle fibers is increased compared to oxidative fibers as a result of chronic strength training. Takada et al. 2 showed that the increases in inorganic phosphate (P i ) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) are associated with an increase in muscle volume following four weeks of resistance training. Haun et al. 11 determined increases in anaerobic energy metabolism enzymes (LDH, phosphofructokinase (PFK)) through resistance training lasting several weeks. Consequently, the energetic flow rate increases due to ATPs and an increased lactate accumulation occurs with unchanged lactate elimination. Based on assumptions and findings, metabolic stress is an important factor in muscle hypertrophy 1 7 11 . The studies suggest that increases in muscle volume are associated with an adaption of the anaerobic energy metabolism.

The rate of lactate accumulation (νLa max ) (also known as the glycolysis rate) can thus be regarded as an indirect measure of glycolysis activity 12 13 . This rate can be determined based on the acute increase in [La+] as a result of the load as a function of the load time (t load ). Thus, the activity of glycolysis can be estimated quite simply on the basis of the change in [La+] as a function of the t load and show the metabolic stress. This measure describes the efficiency of the anaerobic energy metabolism, which increases significantly during strength training and is dependent on movement speed 14 . Good reproducibility of νLa max was shown during isokinetic force loading as well as sprint loading 15 16 . The adaptation of the νLa max has been examined in endurance studies. So far, only one study is available that shows a reduction of νLa max following endurance training that lasted several weeks 17 . This study compared sprint interval (SIT) training with continuous endurance training (CET) and showed that after 6 weeks SIT, there was a significant reduction in the νLa max . This remained unchanged at CET. The adaptation of the νLa max through resistance training lasting several weeks has not yet been investigated.

In resistance training, protocols are generally used that contain different exercise volume load (volume load=set×reps×load; e. g., 2500=5 sets×10 reps×50 kg; load based in% of 1RM) 18 19 . The comparison of training protocols showed that high-volume training causes significantly higher lactate concentrations compared to low volume with high load after the exertion 20 21 . After an 8-week resistance exercise period, Mangine et al. 20 did not observe a change in [La+] immediately after the last exercise session in a high-volume and a strength protocol. This [La+] is the result of the acute load and does not show the efficiency of the anaerobic glycolysis.

With a focus on muscle volume, a few studies examined volume following resistance training with different volume loads. For example, the impact of volume load in resistance exercise was examined 22 . A high-load protocol of 3 sets of 10 reps at 75% of 1 RM was compared with a low load of 4 sets of reps until failure at 30% 1 RM on pectoralis major and triceps brachii hypertrophy. The resistance training lasted 6 weeks with 3 training days per week. The results showed that both resistance training protocols had comparable muscle cross section increases. An another study by Schoenfeld et al. 23 examined different training volumes with a strength training protocol (7 sets, 3 reps at 3 RM) and a hypertrophy training program (3 sets, 10 reps at 10 RM) over 8 weeks (3×weekly). The results showed comparable increases in muscle thickness in the biceps brachii in both groups. Both studies showed no significant impact on muscle hypertrophy at different volume loads. However, adaptations of the energy metabolism based on νLa max have hardly been considered in this context. If metabolic stress is important for muscle hypertrophy, it would be helpful to know how the metabolic measure νLa max adapts through resistance training at different volume loads.

Based on the available studies, it is assumed that resistance training over several weeks leads to a change in glycolytic enzymes and [La+] in the afterload. No statements can be made about the changes in the νLa max caused by resistance training. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of 6 weeks of resistance training with different training volumes load on νLa max . If changes in νLa max are associated with changes in performance from strength training over several weeks, the νLa max could be an important parameter of anaerobic performance in resistance training. It may be possible to assess metabolic adaptations with varying training volumes in strength training using νLa max .

Materials and Methods

Experimental design and subjects

After receiving information and giving written consent to participate in the study, 24 healthy male strength-trained subjects were assigned to one of two groups (high-volume, low-load=HVLL, low-volume, high-load=LVHL) with different training volume loads. HVLL (n=14; age 25.0±4.3 years; height 179.7±7.1 cm; body mass 83.6±11.0 kg; body mass index 25.9±3.1 kg m - ²) trained at 50% of the 1RM with 5 sets and reps up to muscle failure. The subjects in LVHL (n=10; age 24.6±2.8 years; height 178.1±6.0 cm; body mass 80.5±11.2 kg; body mass index 25.4±3.3 kg m - ²) trained at 70% of the 1RM with 5 sets of 10 reps. All test subjects were free of injuries and chronic diseases. Furthermore, all subjects had more than 2 years of training experience and had a training scope of 1 to 4 training units per week at the beginning of the study. The training scope ranged from 1.5 up to 5.0 hours per week. The study meets the ethical standards in sports and exercise science and was approved by the local ethical committee (V-361-17-HSch-νla max -12122019) 24 .

Measurements

Before the intervention, anthropometric data and the one repetition maximum (1RM) were recorded. A maximum isokinetic strength test (Con-Trex® Multi Joint System, Physiomed, Schnaittach, Germany) was performed before and after the intervention to determine anaerobic performance and capacity. A concentric isokinetic strength test was carried out with an ankle velocity of 180°s −1 and 10 reps (15 s load time). The maximum (P max ) and mean maximum power (meanP max , mean of ten reps) of the thigh extensors and flexors were evaluated. P max was standardized to body mass.

To determine the lactate concentration [La+], capillary blood samples (20µl) were taken from the earlobe before [La+] pre , immediately after exercise, and up to the ninth minute post-exercise (up to the third minute at 30-second intervals, from the third to the ninth minute at 60-second intervals). The calculation of the maximum glycolysis rate (νLa max ) was based on the pre-load lactate concentration [La+] pre , maximum lactate concentration in the post-load [La+] max , the loading time (t load ), and the alactic time interval of 3 seconds 13 25 . The reproducibility of the maximum glycolysis rate by an isokinetic strength test showed a high correlation of r>0.67 15 .

Intervention

Two to five days before the training intervention, the 1RM was recorded to calculate the training load for each exercise 26 . Both groups trained their lower extremities 3 times a week for 6 weeks. The strength training program was carried out on sequential machines (Gym80, Gelsenkirchen, Germany). The exercises consisted of leg press (LP), leg extension (LE) and leg flexor (LC, in the prone position) sets and were performed bilaterally in random order. Both training groups performed 5 sets each with a break of 90 seconds between series. HVLL completed the maximum possible number of repetitions until local muscle failure at 50% of the 1RM. LVHL completed 5 sets of 10 repetitions each at 70% of the 1RM. There was a regeneration period of 24 to 48 hours between each training day. The exercise sessions were observed by a practiced coach.

The absolute exercise volume load (EV) was calculated from the product of the training weight (load) and the number of repetitions (rep), which was then summed up over all sets and training sessions (TS) 19 . At relative EV (per TS), the total EV was relativized to TS.

Statistical analysis

The arithmetic mean (mean), standard deviation (±SD), minimum (MIN), and maximum (MAX) were calculated for all data (Microsoft Excel Version 16.0; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The inferential statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The test for normal distribution was performed using the Shapiro Wilk test. Homoscedasticity was checked using Levene’s test. If the test requirements were met, the training group and training time were checked for significant effects on the dependent variables using two-way variance analysis. If the requirements for a parametric test were not met, a Friedman test was used to check for significant main effects. Comparisons between the two groups were then made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Pre-post comparisons within the group were performed using a dependent t-test and Wilcoxon’s test. The effect sizes were determined for pre-post comparisons using Cohen’s d (d). η 2 was used as an effect measure in variance-analytical comparisons. The interpretation of effect size’s based on 27 . The test power for νLa max was determined post-hoc (G*Power, Version 3.1.9.2; Düsseldorf, Germany). Correlation analyses using Spearman (no normal distribution) were used to check for changes in performance associated with changes in νLa max . The level of significance was set at p≤0.05.

Results

There were no significant differences in anthropometric data or performance between the two training groups before the training intervention (p>0.05). The training frequency (TF) after six weeks was 17.07±1.27 (94.9%) in HVLL and 16.8±2.35 (93.3%) in LVHL (p=0.841). The relative EV was 10868±2960 kg for HVLL and 4908±1989 kg for LVHL (p=0.000; d=2.286). HVLL had an approximately 2.2 times higher EV compared to LVHL. In HVLL, this resulted in 18.43±2.93 (13.91–25.92) reps per set and exercise. The LVHL group always completed 10 reps per set and exercise.

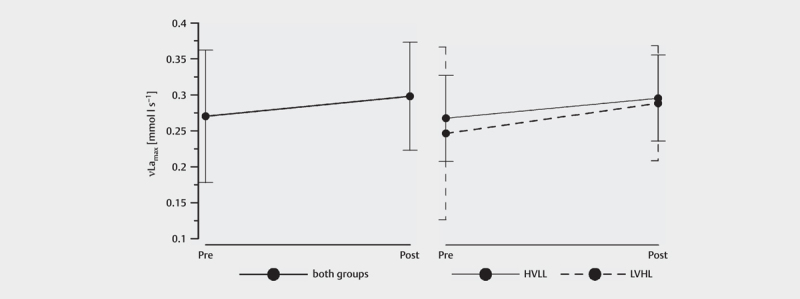

A significant time effect of νLa max was observed after 6 weeks of strength training (p=0.032; d=0.974; η part ²=0.192). νLa max showed an increase from 0.262±0.092 to 0.295±0.075 mmol·l −1 ·s −1 ( Fig. 1 ). In HVLL, νLa max increased significantly (p=0.022; d=0.406), but in LVHL the increase of νLa max was not significant (p=0.233; d=0.384). A significant group effect on νLa max could not be determined (p=0.650; d=0.201; η part ²=0.010).

Figure 1.

Pre-Post comparison of the mean values for νLa max . left means of both groups, right means of group HVLL and LVHL (error bars show the standard deviation)

The [La+] pre showed no significant differences between pre-test and post-test in either group (p>0.05). [La+] max showed a significant time effect (p=0.001; d=0.685; η part ²==0.376). The maximum lactate concentration increased from 3.85±0.965 mmol l −1 to 4.45±0.771 mmol l −1 . [La+] max increased significantly in HVLL (p=0.012; d=0.410; η part ²=0.042) and in LVHL (p=0.039; d=1.03; η part ²=0.212). A significant group effect was not observed for [La+] max (p=0.130; d=0.652; η part ²=0.096).

The isokinetic strength test showed significant time effects of mean P max (p=0.000; d=2.268), relative mean P max (p=0.004; d=1.436), P max (p=0.000; d=2.016), and rel P max (p=0.004; d = 1.436). There was no significant group effect (p>0.05; d<0.4). Significant increases in the parameters of the isokinetic strength test were found within groups (p<0.05) ( Table 1 ). HVLL showed a significant increase in mean P max (p=0.002; d=0.370), relative mean P max (p=0.008; d=0.445), P max (p=0.004; d=0.314) and relative P max (p=0.015; d=0.335). LVHL also showed a significant increase in mean P max (p=0.010; d=0.357), relative mean P max (p=0.008; d=0.421), P max (p=0.027; d=0.361) and relative P max (p=0.009; d=0.440).

Table 1 Result of pre-test and post-test for all estimated parameters. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (min-max).

| HVLL | LVHL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| meanP max (W) | 385.1±74.0 | 416.5±94.6* | 378.8±169.5 | 434.5±141.5 +# |

| (298.8–552.1) | (298.1–641.2) | (156.2–755.9) | (304.4–764.9) | |

| relative mean P max (W·kg −1 ) | 4.60±0.59 | 4.90±0.75* | 4.68±1.77 | 5.35±1.39* # |

| (3.73–5.54) | (3.86–6.00) | (3.73–5.54) | (1.80–3.71) | |

| P max (W) | 424.3±80.2 | 452.3±97.5* | 405.6±173.2 | 462.2±138.7 +~ |

| (342.3–584.8) | (329.2–686.6) | (190.7–797.2) | (330.7–780.0) | |

| relative P max (W·kg −1 ) | 5.08±0.69 | 5.33±0.80* | 5.01±1.77 | 5.70±1.34* # |

| (4.04–6.26) | (4.26–6.43) | (2.20–8.17) | (4.02–8.03) | |

| [La+] pre (mmol·l −1 ) | 0.59±0.17 | 0.68±0.18 | 0.96±0.22 | 0.94±0.34 |

| (0.50–1.90) | (0.55–1.53) | (0.60–1.33) | (0.50–1.51) | |

| νLa max (mmol·l −1 ·s −1 ) | 0.271±0.067 | 0.298±0.067* | 0.249±0.122 | 0.291±0.089 ~ |

| (0.133–0.371) | (0.196–0.421) | (0.034–0.465) | (0.104–0.402) | |

| [La+] max (mmol·l −1 ) | 4.03±0.859 | 4.4±0.887* | 3.61±1.09 | 4.53±0.611*~ |

| (2.21–5.16) | (2.95–6.05) | (1.54–5.33) | (3.7–6.09) | |

* pre vs. post: p<0.05 by t-test; + pre vs. post p<0.05 by Wilcoxon test; ~ time effect for both groups by ANOVA; # time effect for both groups by Friedman test.

A correlation analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between P max and νLa max prior to the training intervention in LVHL (r=0.716; p=0.02). This was not found in HVLL (r=0.189; p=0.521). In addition, a significant correlation between ΔνLa max and ΔP max was found across all subjects (r=0.502; p=0.012).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of 6 weeks of resistance training with different training volume loads on νLa max . The νLa max showed a significant time effect, but a significant group effect was not found. The increases in performance were in a mean linear relationship to the adaptation of the anaerobic energy metabolism using the νLa max . Thus, νLa max as a physiological measure of anaerobic energy metabolism seems to be a significant performance parameter.

We presume that the significant performance increases in the isokinetic strength test are the result of more activated muscle fibers 28 . The higher number of active muscle fibers results in greater anaerobic activity, as shown by the post-test increases in [La+]. Hommel et al. 17 found a significant reduction of νLa max after 2 weeks in sprint interval training, which was stabilized up to sixth week with increased maximal performance; oxygen uptake (VO 2max ) was unchanged. The extent to which the resistance training changed the VO 2max cannot be answered, because the maximal oxygen uptake was not measured here. Ozaki et al. showed in an overview that changes in VO 2max due to resistance exercise lasting several weeks were only available for untrained subjects 29 . There were inconsistent results in relation to the training volume. In part, no changes but also slight increases in VO 2max were found. Furthermore, no significant change in mitochondria enzyme activity (e. g., citrate synthase and succinate dehydrogenase) was reported following RT, which has the potential to increase VO 2max [ 30 31 . Due to the design of our study, it is not clear which temporal dynamics the adjustment of the maximum glycolysis rate has during the training period. This would have required measurements of anaerobic performance at intervals of one or two weeks.

In a six-week study with resistance training, muscle biopsy analyses showed adaptations of the anaerobic energy metabolism and hypertrophy of the muscle fibers. Numerous enzymes of the lactacid energy metabolism (e. g., PFK, LDH) increased their activities 11 . It is assumed that the higher activity of anaerobic enzymes causes an increase in glycolysis activity. This then results in a time-dependent increase in the maximum glycolysis rate. For muscular work, this means more available ATP over the loading period. An increase in glycolytic enzymes is a possible explanation for the increased maximum glycolysis rate after the training intervention in both groups. However, the increases in glycolytic enzymes, such as PFK, appear to be only marginally caused by chronic strength training 10 32 . Oxidative and therefore also metabolic stress is considered relevant for hypertrophic muscle adaptation 33 . However, it is important to point out that other factors are also of high importance for muscle hypertrophy. These include the influence of amino acids intake, growth hormone concentrations, and mechanical stress 34 .

There was a high effect size (d=0.97) of resistance training on νLa max for both groups (all subjects). Within both groups, this was considered a medium effect (d=0.38 – 0.40). Statements about which training protocol is more effective in increasing anaerobic performance cannot be made at present. No significant differences between groups were found for νLa max . The post hoc power analysis showed that a variance-analytical comparison between the two groups would have required more than 500 subjects (for p-value of 0.05; d=0.2) to show significant differences. The data show that there was a high dispersion of νLa max within LVHL, which indicates a heterogeneous study cohort. A more homogeneous subject cohort may also have resulted in a significant increase in group LVHL. Scott et al. 19 pointed out that heterogeneous subjects in a resistance exercise protocol are problematic. Subjects can certainly be selected based on their training status; an assignment based on glycolysis activity currently seems difficult to us.

There are currently no studies that directly examine the effects of resistance training on νLa max . However, acute studies show that lower loads with exhaustive reps lead to significantly higher metabolic stress (lactate concentration) than higher loads with few reps 35 . It was also shown that higher reps (5 sets of 10 reps) compared to lower reps (10 sets of 5 reps) at the same load also lead to increased metabolic stress. This was reflected in a stronger reduction of ATP and PCr. The significantly higher [La+] at 5 sets of 10 reps indicates the increased stress on glycolytic enzymes 36 . A training experiment at 70% of 1RM (with high volume) and 90% of 1RM (with low volume) led to similar results 21 . In this training study, the strong [La+] increases found in acute studies at high EV did not lead to significantly different adjustments of νLa max between EV. The variations in load and volume used here are not directly comparable with existing studies. In order to clearly show the influence of the volume load, loads above 70% of the 1RM and below 50% of the 1RM in the other group should have been chosen.

The increases in La max due to training interventions are possibly the result of increased glycolysis and have already been noted in previous studies 37 . If we presume that training-related changes in anaerobic enzymes occur only to a small extent 10 , it cannot be ruled out that untrained volunteers would have shown more marked adjustments to νLa max . Lactate as an intermediate product of glycolysis and its change in [La+] over the t load is considered here in this highly intensive anaerobic test (maximum one-legged strength test) as a measure of glycolysis activity. Adjustments of the anaerobic enzyme activities that regulate [La+] can only be speculated in this study. In the future, a 31 phosphorus -magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) may help show concentrations of energetic substrates before and after several weeks of training. It should also be mentioned that lactate concentrations determined from capillary blood are dependent on the time constant of elimination. Furthermore, the lactate formed in the muscle is transported through different compartments 38 . Thus, the lactate concentrations determined from capillary blood will be lower than the acute reactions produced by the test in the muscle under stress 39 . Furthermore, there was no control of food intake in this study, there may be influences of increased or reduced glucose intake on [La+] 40 .

Conclusions

Based on the available data, six weeks of resistance training of the lower extremities can increase anaerobic performance using the glycolysis rate. Effects of the volume load could not be determined. Thus, the effectiveness of training protocols with high or low training-volume loads on νLa max cannot yet be assessed.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrea Ludwig for support recording data.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Freitas de M C, Gerosa-Neto J, Zanchi N Eet al. Role of metabolic stress for enhancing muscle adaptations: Practical applications World J Methodol 2017746–54.. doi:10.5662/wjm.v7.i2.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada S, Okita K, Suga Tet al. Low-intensity exercise can increase muscle mass and strength proportionally to enhanced metabolic stress under ischemic conditions J Appl Physiol 2012113199–205.. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00149.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagisawa O, Sanomura M. Effects of low-load resistance exercise with blood flow restriction on high-energy phosphate metabolism and oxygenation level in skeletal muscle. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2017;9:67–75. doi: 10.1556/1646.9.2017.2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arazi H, Mirzaei B, Heidari N. Neuromuscular and metabolic responses to three different resistance exercise methods. Asian J Sports Med. 2014;5:30–38. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogatzki M J, Wright G A, Mikat R P et al. Blood ammonium and lactate accumulation response to different training protocols using the parallel squat exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:1113–1118. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a1f84e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wirtz N, Wahl P, Kleinöder H et al. Lactate kinetics during multiple set resistance exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:73–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crewther B, Cronin J, Keogh J.Possible stimuli for strength and power adaptation: Acute metabolic responses Sports Med 20063665–78.. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes T, Soci U, Melo Set al. Signaling pathways that mediate skeletal muscle hypertrophy: effects of exercise trainingInCseri Jed.Skeletal Muscle - From Myogenesis to Clinical Relations London: InTech; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgomaster K A, Howarth K R, Phillips S Met al. Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans J Physiol 2008586151–160.; doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesch P A. Skeletal muscle adaptations consequent to long-term heavy resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20:132–134. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198810001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haun C T, Vann C G, Osburn S Cet al. Muscle fiber hypertrophy in response to 6 weeks of high-volume resistance training in trained young men is largely attributed to sarcoplasmic hypertrophy PLoS One 201914e0215267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heck H, Schulz H. Diagnostics of anaerobic power and capacity. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2002;53:202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mader A.Aussagekraft der Laktatleistungskurve in Kombination mit anaeroben Tests zur Bestimmung der StoffwechselkapazitätInClasing DEd.Stellenwert der Laktatbestimmung in der Leistungsdiagnostik: 32 Tabellen. Stuttgart u. a.: G. Fischer 1994133–152. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitzsche N, Zschäbitz D, Baumgärtel Let al. The effect of isokinetic resistance load on glycolysis rateInet al. , (Eds.)22nd Annual Congress of the European College of Sport Science: 5–8th July 2017, Metropolis Ruhr - Germany: book of abstracts Bochum: Bochumer Universitätsverlag Westdeutscher Universitätsverlag; 2017. 558 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitzsche N, Baumgärtel L, Maiwald Cet al. Reproducibility of blood lactate concentration rate under isokinetic force loads Sports 201861–8.. doi:10.3390/sports6040150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam J, Ohmichen M, Ohmichen Eet al. Reliability of the calculated maximal lactate steady state in amateur cyclists Biol Sport 20153297–102.; doi:10.5604/20831862.1134311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hommel J, Öhmichen S, Rudolph U Met al. Effects of six-week sprint interval or endurance training on calculated power in maximal lactate steady state Biol Sport 20193647–54.. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2018.78906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACSMProgression models in resistance training for healthy adults Med Sci Sports Exerc 200941687–708.. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott B R, Duthie G M, Thornton H Ret al. Training monitoring for resistance exercise: theory and applications Sports Med 201646687–698.. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0454-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangine G T, Hoffman J R, Gonzalez A Met al. The effect of training volume and intensity on improvements in muscular strength and size in resistance-trained men Physiol Rep 20153e12472. doi:10.14814/phy2.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez A M, Hoffman J R, Townsend J Ret al. Intramuscular anabolic signaling and endocrine response following high volume and high intensity resistance exercise protocols in trained men Physiol Rep 20153e12466. doi:10.14814/phy2.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogasawara R, Loenneke J P, Thiebaud R Set al. Low-load bench press training to fatigue results in muscle hypertrophy similar to high-load bench press training Int J Clin Med 201304114–121.. doi:10.4236/ijcm.2013.42022 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenfeld B J, Ratamess N A, Peterson M Det al. Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men J Strength Cond Res 2014282909–2918.. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harriss D J, MacSween A, Atkinson G.Ethical standards in sport and exercise science research: 2020 update Int J Sports Med 201940813–817.. doi:10.1055/a-1015-3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nitzsche N, Zschäbitz D, Baumgärtel Let al. Einfluss der Methode zur Bestimmung des alaktaziden Zeitintervalls bei isokinetischen KraftbelastungenInet al. Eds.Innovation & Technologie im Sport Hamburg: Feldhaus Edition Czwalina; 2017. 215 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haff G G, Triplett N T.Eds.Essentials of strength training and conditioning4th ed.Champaign, IL, Windsor, ON, Leeds: Human Kinetics; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J.Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd ed.,Hoboken: Taylor and Francis; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tesch P A, Thorsson A, Essén-Gustavsson B.Enzyme activities of FT and ST muscle fibers in heavy-resistance trained athletes J Appl Physiol 19896783–87.. doi:10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozaki H, Loenneke J P, Thiebaud R Set al. Resistance training induced increase in VO2max in young and older subjects Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 201310107–116.. doi:10.1007/s11556-013-0120-1 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell G J, Syrotuik D, Martin T Pet al. Effect of concurrent strength and endurance training on skeletal muscle properties and hormone concentrations in humans Eur J Appl Physiol 200081418–427.. doi:10.1007/s004210050063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson A G, Arnall D A, Loy S Fet al. Consequences of combining strength and endurance training regimens Phys Ther 199070287–294.. doi:10.1093/ptj/70.5.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tesch P A, Alkner B A.Acute and chronic muscle metabolic adaptations to strength trainingInKomi PVEd.Strength and Power in Sport Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2003265–280. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoppeler H, Baum O, Lurman Get al. Molecular mechanisms of muscle plasticity with exercise Compr Physiol 201111383–1412.. doi:10.1002/cphy.c100042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoppeler H.Molecular networks in skeletal muscle plasticity J Exp Biol 2016219205–213.. doi:10.1242/jeb.128207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buitrago S, Wirtz N, Yue Z et al. Effects of load and training modes on physiological and metabolic responses in resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;7:2739–2748. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorostiaga E M, Navarro-Amézqueta I, Calbet JA Let al. Energy metabolism during repeated sets of leg press exercise leading to failure or not PLoS One 20127e40621. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nitzsche N, Jürgens S, Schulz H.Effekte eines achtwöchigen progressiven Rope-Trainings auf die Leistungsfähigkeit der oberen Extremitäten Ger J Exerc Sport Res 201949493–502.. doi:10.1007/s12662-019-00587-0 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zouloumian P, Freund H. Lactate after exercise in Man: II. Mathematical model. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1981;46:135–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00428866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bangsbo J, Johansen L, Graham T et al. Lactate and H+effluxes from human skeletal muscles during intense, dynamic exercise. J Physiol. 1993;462:115–133. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikulski T, Ziemba A, Nazar K. Influence of body carbohydrate store modification on catecholamine and lactate responses to graded exercise in sedentary and physically active subjects. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59:603–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]