ABSTRACT

Background

β-Glucans (BGs), a group of complex dietary polysaccharides (CDPs), are available as dietary supplements. However, the effects of orally administered highly purified BGs on gut inflammation are largely unknown.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of orally administering highly purified, yeast-derived BG (YBG; β-1,3/1,6-d-glucan) on susceptibility to colitis.

Methods

Eight-week-old C57BL/6 (B6) mice were used in a series of experiments. Experiment (Expt) 1: male and female mice were treated every day, for 40 d, with saline (control) or 250 μg YBG, followed by 2.5% (wt:vol) dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water during days 30–35; and colitis severity and intestinal immune phenotype were determined. Expt 2: female B6 mice were treated with saline or YBG for 30 d and intestinal immune phenotype, gut microbiota composition, and fecal SCFA concentrations were determined. Expt 3: female B6 mice were treated as in Expt 2, given drinking water with or without antibiotics [Abx; ampicillin (1 g/L), vancomycin (0.5 g/L), neomycin (1 g/L), and metronidazole (1 g/L)] during days 16–30, and gut immune phenotype and fecal SCFA concentrations were determined. Expt 4: female B6 Foxp3–green fluorescent protein (-GFP) reporter mice were treated as in Expt 3, and intestinal T-regulatory cell (Treg) frequencies and immune phenotypes were determined. Expt 5: female mice were treated as in Expt 1, given drinking water with or without antibiotics during days 16–40, and colitis severity and intestinal cytokine production were determined.

Results

Compared with controls, the YBG group in Expt 1 exhibited suppressive effects on features of colitis, such as loss of body weight (by 47%; P < 0.001), shortening of colon (by 24%; P = 0.016), and histopathology severity score (by 45%; P = 0.01). The YBG group of Expt 2 showed a shift in the abundance of gut microbiota towards Bacteroides (by 16%; P = 0.049) and Verrucomicrobia (mean ± SD: control = 7.8 ± 0.44 vs. YBG = 21.0 ± 9.6%) and a reduction in Firmicutes (by 66%; P < 0.001). The YBG group also showed significantly higher concentrations of fecal SCFAs such as acetic (by 37%; P = 0.016), propionic (by 47%; P = 0.026), and butyric (by 57%; P = 0.013) acids. Compared with controls, the YBG group of Expt 2 showed higher frequencies of Tregs (by 32%; P = 0.043) in the gut mucosa. Depletion of gut microbiota in the YBG group of mice caused diminished fecal SCFA concentrations (Expt 3) and intestinal Treg frequencies (Expt 4). Compared with the YBG group, the YBG-(Abx) group of Expt 5 showed aggravated colitis features including loss of body weight (by >100%; P < 0.01) and colonic inflammation score (by 42%; P = 0.04).

Conclusions

Studies using B6 mice show that dietary BGs are beneficial for promoting intestinal health when the gut microbiota is intact. However, these CDPs may produce adverse effects if gut microbiota is compromised.

Keywords: yeast β-glucan, gut mucosa, gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acid, colitis, gut inflammation, immune modulation, immune regulation

Introduction

Dietary approaches have increasingly been considered for modulating immune function and preventing autoimmunity and other clinical conditions. β-Glucans (BGs) are nondigestible complex dietary polysaccharides (CDPs) of varying structures (β-1,3-d-glucan, β-1,3/1,6-d-glucan, β-1,3/1,4-d-glucan, and β-1,4-d-glucan) and are commonly found in plants, cereals, bacteria, yeast, and fungi (1). While BGs can potentiate the function of the immune system directly (2, 3), BG-containing preparations have been promoted also as daily dietary supplements to enhance metabolic functions and as prebiotics (4). On the other hand, clinical studies using YBG preparations reported conflicting outcomes in terms of their potential benefits as dietary supplements (5–9). Studies using animal models to determine the potential of BG preparations and BG-containing diets to modulate gut inflammation have also produced conflicting outcomes (10–15). Furthermore, inconsistent results on colitis susceptibility of Dectin-1 (BG interacting receptor) knockout mice have been reported (16, 17).

Differences observed in the impact of BG dietary supplements on host health could be due to multiple factors, including the following: 1) purity and/or the structure of the BG employed, 2) degree of direct interactions of those BG preparations with host receptors, and 3) possible association between gut microbes and BG-induced effects in the host and differences in the structure and function of basal gut microbiota. Determination of the true effect of consuming dietary BGs thus requires systematic preclinical studies using well-defined highly purified BGs. Further, studying the direct immune-modulatory effect of BGs on gut mucosa and the indirect, microbiota-dependent, effect is necessary to better understand the mechanisms of immune modulation induced by these CDPs. Such studies will also help explain the contradictory effects of these agents on the host. For this study, we hypothesized that oral administration of a highly purified BG [β-1,3-linked d-glucose molecules (β-1,3-d-glucan) with β-1,6-linked side chains] from Baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (YBG) prevents autoimmunity (18, 19). It can enhance immune modulation by directly interacting with the gut mucosa and by serving as a fermentation substrate for gut commensals that produce immune-regulatory metabolites. Therefore, we examined the impact of orally administering highly purified YBG on gut inflammation by employing dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)–induced colitis in C57BL/6 (B6) mice as the model, and assessed the contribution of gut microbiota to YBG consumption–associated enhanced gut immune regulation and suppression of colitis susceptibility.

Methods

Mice

B6 mice were originally purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Foxp3-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-knockin (Foxp3-GFP) mice in a B6 background were provided by Dr Vijay Kuchroo (Harvard Medical School). Breeding colonies of these strains were established and maintained in the pathogen-free facility of Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Mice were fed an autoclaved rodent diet (20), which contains 18.6% (wt:wt) protein, 6.2% (wt:wt) fat, and 44.2% (wt:wt) carbohydrates (Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent diet no. 2018; Harlan Laboratories), and autoclaved water ad libitum. For most experiments, mice were housed in groups (≤5 mice/cage). However, for studies involving microbiota and SCFA analysis, mice were housed individually (1 mouse/cage). All animal studies were approved by the animal care and use committee at MUSC. Since B6 mice are highly susceptible to DSS-induced distal gut inflammation and have been widely used as a model of ulcerative colitis (UC) (21–24), we employed this strain for determining the impact of YBG on DSS-induced colitis. While most experiments described in this study used age-matched females for control and test groups, our initial experiments showed YBG treatment induced similar protection in male B6 mice from colitis. However, since mortality was as high as 50% by day 10 with control males with DSS colitis, to be able to compare similar numbers of controls and YBG-treated mice side-by-side, we used females for this study. B6-Foxp3-GFP reporter mice that express GFP under Foxp3 promoter and only in regulatory T cells (Tregs) were used in an experiment to visualize and enumerate Tregs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) unambiguously.

YBG and other reagents

Purified YBG (glucan from Baker's yeast, S. cerevisiae), ≥98% pure, was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and the purification method has been described before (18). This agent was tested for specific activity using thioglycolate-activated macrophages, as described before by us and others (25–27). DSS salt of 36,000–50,000 MW was purchased from MP Biomedicals. Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), ionomycin, Brefeldin A, and purified and conjugated antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, BD Biosciences, eBioscience, Invitrogen, R&D Systems, and Biolegend Laboratories. In some experiments, intestinal epithelial cells were depleted by Percoll gradient centrifugation (28) or using A33 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-rabbit IgG-magnetic beads (29, 30). Oligonucleotide probes for qPCR were custom synthesized by Invitrogen. Magnetic bead–based multiplex assay kits were purchased from Invitrogen. Additional details of commercial products used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Treatments using YBG, DSS, and antibiotics

YBG was administered daily, by oral gavage, as a single dose of a 250-μg suspension in 200 μL saline. This dose of YBG was considered because it is a human-relevant dose of BG dietary supplements at 500–1000 mg, equaling ∼10 mg (per kg body weight) per day. Further, as mentioned in our previous report (29), lower doses or short-term treatments do not produce observable immune modulation in the gut mucosa. We also found that even a very short-term (3-d) treatment with a higher daily dose such as 2000 μg/d produces a proinflammatory response in the gut mucosa in a Dectin-1–dependent manner (29); hence, a relatively lower daily dose was used for this study.

Eight-week-old mice were used in the following series of experiments (Expts) involving the treatments.

Expt 1

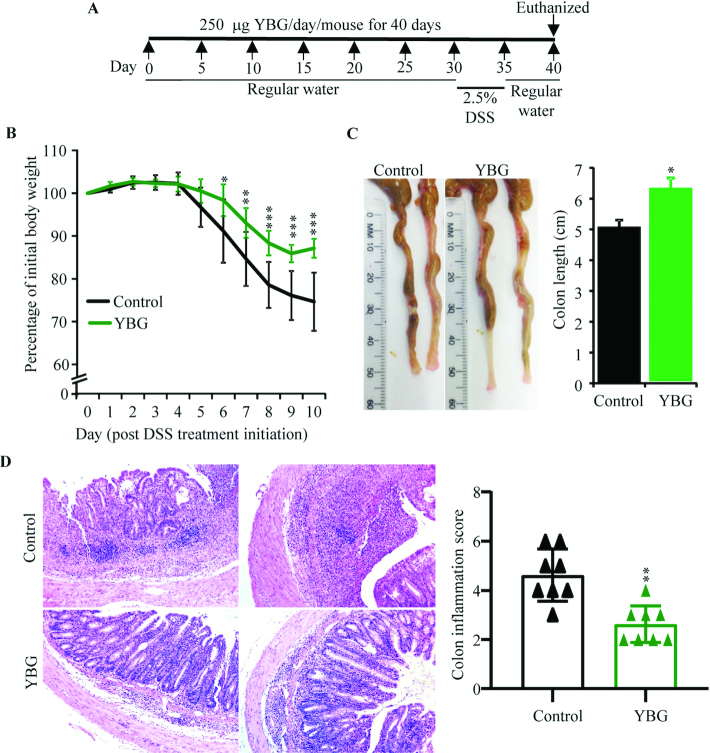

As depicted in Figure 1A, male and female B6 mice (n = 8/group) were treated every day with saline (control group) or 250 μg YBG suspension in saline (YBG group) for 40 d, and given 2.5% DSS in drinking water (wt:vol) during days 30–35. Body weight, stool consistency, and presence of occult blood were determined every day from days 30 to 40. Mice were killed on day 40, intestinal tissues were collected, the colon lengths were measured, and distal colon tissues were subjected to histochemical staining to determine the severity of inflammation. Distal colon tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde, and 5-μm paraffin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Stained sections were analyzed using the 0–6 grading criteria described before (31) for inflammatory cell infiltrates, epithelial changes, and mucosal architecture, and values were averaged to calculate the overall inflammation score of individual mice. Gut-associated immune cells were subjected to immunological assays as described below.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of pretreatment with YBG (A) on DSS-induced colitis–associated weight loss (B), colon shortening (C), and colon inflammation (D) in B6 mice (Expt 1). (A) Experimental design. (B) Body weights of individual mice were measured every day starting at day 30, and changes in percentage of body weight, relative to initial body weight, are shown. (C) Images of representative colons (left panel) and colon lengths (right panel) of killed mice are shown. (D) H&E-stained distal colon sections were evaluated for inflammation, and images of representative sections (left panel) and inflammation severity scores (right panel) are shown. (B; right panels of C, D) Values are means ± SDs (n = 8). *,**,***Different from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; Expt, experiment; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

Expt 2

Female B6 mice (n = 8/group) were treated with saline or YBG for 30 d, and fresh fecal pellets were collected from individual mice for microbial community and SCFA profiling as described below. Mice were killed on day 30, and immune phenotypes of intestinal tissues and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were determined as described below.

Expt 3

Female B6 mice (n = 5/group) were treated with saline or YBG for 30 d as in Expt 2. In addition, these mice were given drinking water without (“none” group) or with antibiotics [Abx group; ampicillin (1 g/L), vancomycin (0.5 g/L), neomycin (1 g/L), and metronidazole (1 g/L)] during days 16–30 to deplete the gut microbiota. Suspensions of fecal pellets collected from individual mice on day 25 were cultured under aerobic and anaerobic conditions to assess the microbiota depletion (29). Fresh fecal pellets were collected from individual mice on day 30 for SCFA analysis. Mice were killed on day 30, and immune phenotypes of intestinal tissues and MLNs were determined as described below.

Expt 4

Female Foxp3-GFP reporter mice (n = 5/group) were treated with saline or YBG for 30 d and given drinking water without or with antibiotics during days 16–30 as in Expt 3. Mice were killed on day 30 and intestinal Treg frequencies were determined by FACS as described below.

Expt 5

Female B6 mice (n = 5/group) were treated with saline or YBG for 40 d as in Expt 1 and given drinking water with or without antibiotics during days 16–40 and DSS-containing drinking water during days 30–35. The severity of colitis-associated symptoms was determined as in Expt 1. Mice were killed on day 40, and the severity of gut inflammation and cytokine profiles of intestinal immune cells were determined.

Immunological assays and qPCR

Cells from the small intestinal lamina propria (SiLP), large intestinal lamina propria (LiLP), and MLNs from various experiments were examined for immune cell phenotype and/or cytokine profiles by FACS and multiplex assay, respectively, as described in our recent reports (29, 30, 32). Briefly, for determining Treg frequencies, freshly isolated cells from B6 mice (n = 6/group; Expt 1) and B6-Foxp3-GFP mice (n = 5/group; Expt 4) were stained for CD4 and/or Foxp3. For determining the cytokine-positive T-cell frequencies, cells from B6 mice (n = 6/group; Expt 1) were cultured in the presence of PMA, ionomycin, and Brefeldin A for 4 h, before staining for CD4 and intracellular cytokines. For determining secreted cytokine concentrations, cells from B6 mice [n = 6/group (Expt 1); n = 5/group (Expt 5)] and B6-Foxp3-GFP (n = 5/group; Expt 4) mice were cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody for 24 h, and the spent media was subjected to cytokine multiplex assays (Invitrogen) using FlexMap 3D instrument (Luminex). A SYBR green–based qPCR assay was run in a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR machine (BioRad) for determining the cytokine gene expression levels in RNA that was prepared from cryopreserved intestinal tissues from B6 mice (n = 4/group; Expt 2).

16S ribosomal RNA gene targeted sequencing and bacterial community profiling

Three fresh fecal pellets were collected in a single tube from each individually housed mouse of Expt 2 for DNA preparation. Total DNA was prepared from fecal pellets for 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene targeted sequencing and bacterial community profiling as detailed in our previous reports (19, 33, 34), with minor modifications. Briefly, the sequencing reads of control and YBG-treated mice (n = 5/group; day 0 and day 30 time points) were fed into the Metagenomics application of BaseSpace (Illumina) for performing taxonomic classification of the 16S rRNA targeted amplicon reads using an Illumina-curated version of the GreenGenes taxonomic database, which provided raw classification output at multiple taxonomic levels. The sequences were also fed into QIIME open reference operational taxonomic units (OTUs) picking pipeline (35) using preprocessing application of BaseSpace. The OTUs were compiled to different taxonomical levels based upon the percentage of identity to GreenGenes reference sequences (i.e., >97% identity), and the percentage values of sequences within each sample that map to respective taxonomical levels were calculated. The OTUs were also normalized and used for metagenomes prediction of KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) orthologs employing PICRUSt (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States), as described before (36–39). The predictions were summarized to multiple levels, and functional categories were compared between control and YBG-fed groups using the Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profile Package (STAMP), as described before (37, 40).

Determination of fecal SCFA concentrations

Three fresh fecal pellets were collected in a single tube from each individually housed mouse (n = 5/group), stored at −80°C, and shipped on dry ice to Microbiome Insights (Vancouver, Canada) for SCFA analysis. SCFAs were detected by this service provider using GC (Thermo Trace 1310), coupled to a flame ionization detector, using a Thermo TG-WAXMS A GC Column by following a previously described method (41).

Statistical analysis

Two means were compared for all panels of all figures using Prism (GraphPad), Excel (Microsoft), STAMP (37, 40), and/or MicrobiomeAnalyst (42) applications. We employed unpaired, 2-tailed nonparametric Mann-Whitney test for all comparisons, except for the following panels. For Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 2A, a t test (unpaired, 2-tailed) was employed to compare means of weight loss between 2 groups at each time point separately. For Figures 1D and 6C, 2-tailed Fisher's exact test was employed to compare mice with grade ≤3 and ≥4 colon histopathology scores in 2 groups. Log-rank test was employed for comparing the survival rates in Supplemental Figure 2B. For Figure 4, mean abundances of individual microbial communities at different taxa levels, as well as at specific metabolic pathway representations, were determined employing 2-sided Welch's t test and false discovery rate–corrected using the Benjamini and Hochberg approach employing STAMP. β-Diversity (Bray Curtis distance) analysis for Supplemental Figure 5A and α-diversity analysis for Supplemental Figure 5B were performed by permutational multivariate ANOVA and Mann-Whitney approaches, respectively, employing MicrobiomeAnalyst. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

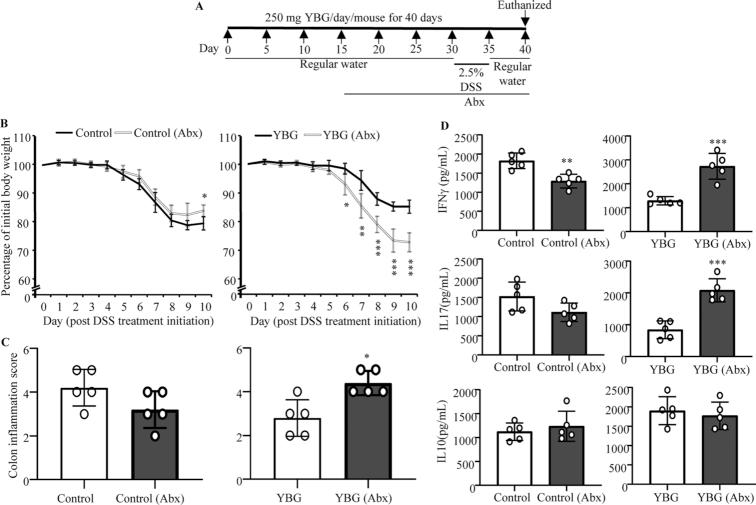

FIGURE 6.

Effect of microbiota depletion (A) in DSS colitis–induced weight loss (B), colon inflammation (C), and cytokine secretion by intestinal immune cells (D) in control and YBG-treated B6 mice (Expt 5). (A) Experimental design. (B) Body weights of individual mice were measured every day starting at day 30, and changes in percentage of body weight, relative to initial body weight, are shown. (C) H&E-stained distal colon sections were evaluated for inflammation, and the severity scores are shown. (D) Concentrations of indicated cytokines secreted by colonic immune cells upon ex vivo stimulation using anti-CD3 antibody are shown. (B–D) Values are means ± SDs (n = 5). *,**,***Different from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Abx, antibiotics; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; Expt, experiment; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

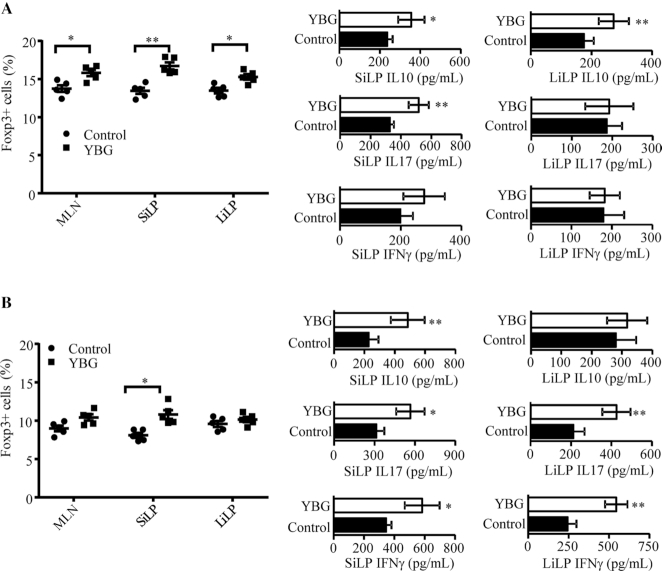

FIGURE 4.

Impact of oral administration of YBG on the Treg frequency and cytokine secretion profile of immune cells in B6 mice with intact (A) and depleted (B) gut microbiota (Expts 3 and 4). (A, B) Foxp3+ CD4 T-cell frequencies in gut-associated lymphoid tissues (MLN, SiLP, and LiLP) were determined by FACS (left panels) and the level of indicated cytokines secreted by MLNs upon stimulation using anti-CD3 antibody was determined by multiplex assay (right panels) are shown. Values are means ± SDs (n = 5) for all panels. *,**Different from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Expt, experiment; LiLP, large intestinal lamina propria; MLN, mesenteric lymph node; SiLP, small intestinal lamina propria; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

Results

Prolonged pretreatment with YBG diminishes the susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis in B6 mice

In Expt 1, 8-wk-old female B6 mice were orally administered with YBG and colitis was induced by treatment with drinking water containing DSS as depicted in Figure 1A. The impact of pretreatment with YBG on colitis susceptibility was determined by examining the mice for gut inflammation–associated features. As observed in Figure 1B, YBG-treated mice showed relatively less weight loss compared with control mice. Significant differences in body weight between control and YBG-treated groups were observed starting day 6 (P = 0.027), which peaked at day 10 (P < 0.001). As shown in Figure 1C, YBG-treated mice also showed significant resistance to colitis-associated shortening of the colon compared with that of control mice (P = 0.016). Overall, DSS-induced histological injury scores of YBG-treated mice were significantly lower (P = 0.016) than those of the control group (Figure 1D). The colons of DSS-treated control mice exhibited more severe inflammatory infiltrates and ulceration compared with those of YBG-treated mice. Further, compared with DSS-treated control mice, better stool consistency (Supplemental Figure 1A) and less fecal blood (Supplemental Figure 1B) were detected in YBG-fed mice that were treated with DSS at the time point in which these features were most severe. Of note, although prolonged pretreatment of male B6 mice with YBG produced similar protection as that of their B6 female counterparts, the control group showed 50% mortality prior to termination of the experiment (Supplemental Figure 2). Further, we also observed that when YBG treatment was initiated concomitantly with colitis induction, but not pretreated, B6 mice showed no difference in the severity of colitis-associated parameters compared with control mice (Supplemental Figure 3).

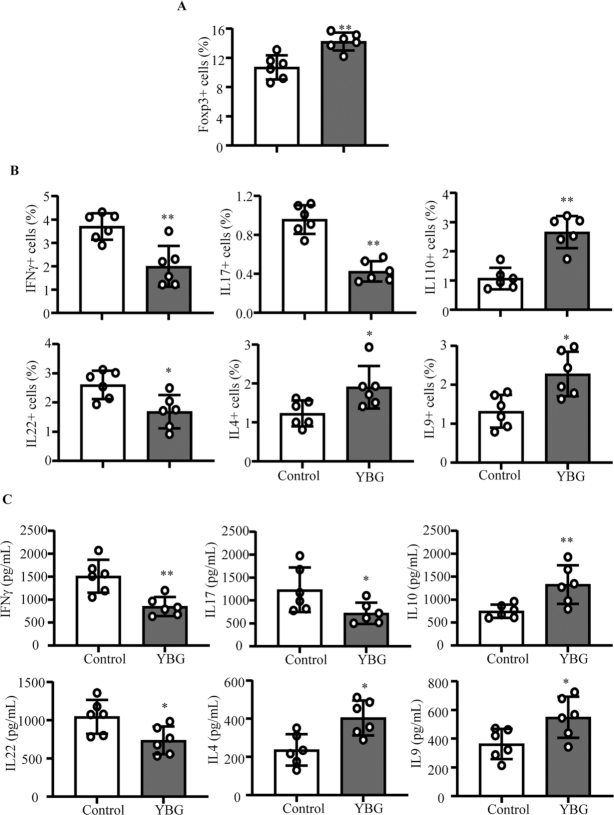

YBG-treated and control B6 mice with colitis showed distinct immune characteristics

Since B6 mice that were pretreated with YBG showed less-severe colon inflammation in Expt 1, T cells from their gut-associated MLNs were examined for phenotypic properties. As shown in Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 4, Foxp3+ Treg frequencies were significantly higher in the MLNs of YBG-fed mice (P = 0.0043) compared with control mice. FACS analyses revealed significantly higher frequencies of IL10+ (P = 0.0043), IL4+ (P = 0.041), and IL9+ (P = 0.015) and lower IFNγ+ (P = 0.0087), IL17+ (P = 0.0022), and IL22+ (P = 0.0152) T-cell frequencies in YBG-fed mice compared with controls (Figure 2B). To validate these observations, the amount of cytokines secreted by MLN cells was determined. Multiplex cytokine assay revealed significantly higher secretion of IL10 (P = 0.0087), IL4 (P = 0.0152), and IL9 (P = 0.041) and lower IFNγ (P = 0.0087), IL17 (P = 0.041), and IL22 (P = 0.026) by MLN cells from YBG-fed mice compared with that of control mice upon ex vivo activation using anti-CD3 antibody (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of YBG pretreatment on Treg (A) and cytokine-expressing CD4+ cell (B) frequencies in and cytokine secretion by (C) MLN cells of B6 mice with DSS-induced colitis (Expt 1). (A, B) Frequencies of CD4+ cells in the MLN single-cell suspension that express indicated factors as determined by FACS are shown. (C) Concentrations of indicated cytokines secreted by MLN cells upon ex vivo stimulation using anti-CD3 antibody are shown. Values are means ± SDs (n = 5) for all panels. *,**Different from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; Expt, experiment; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; MLN, mesenteric lymph node; Treg, regulatory T cell; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

Prolonged YBG treatment results in changes in the fecal microbiota composition in B6 mice

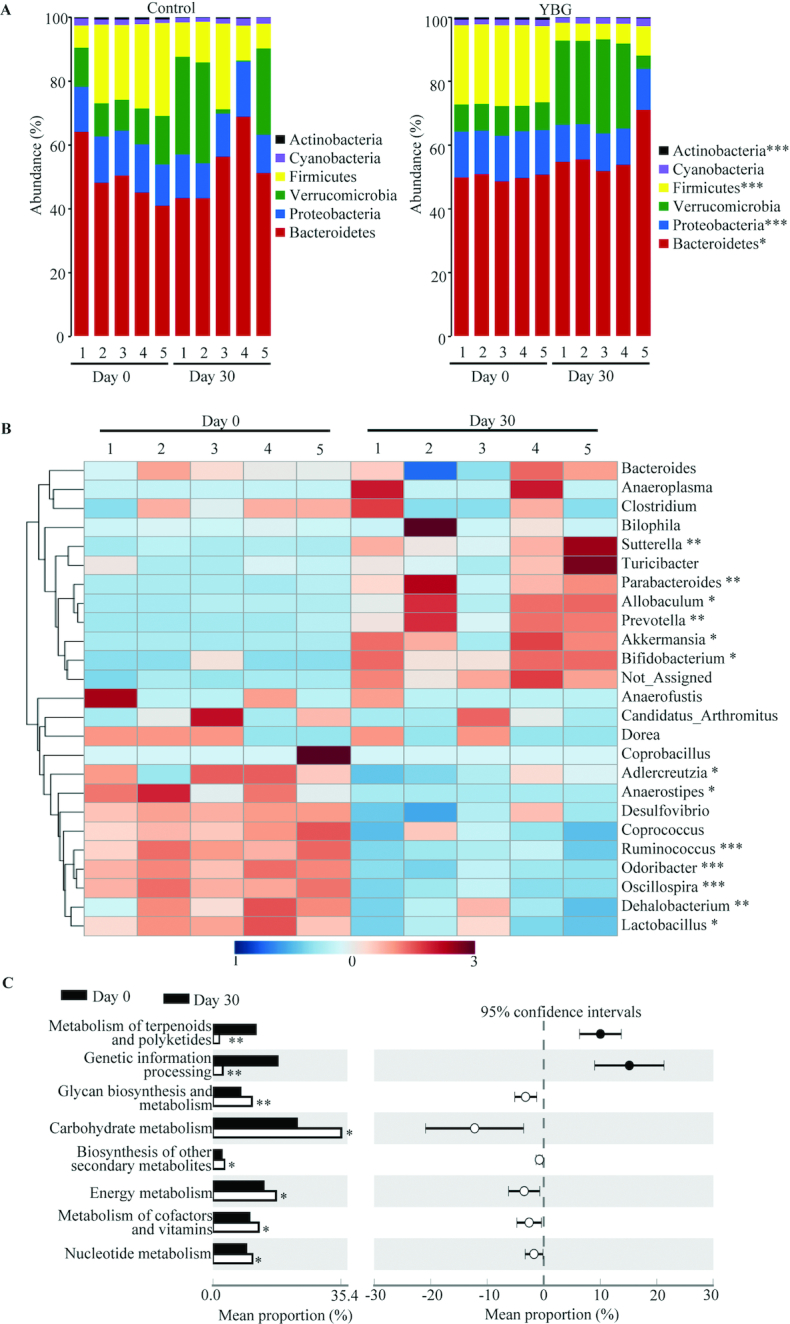

Since only the prolonged treatment with YBG prior to inducing colitis using DSS reduced the susceptibility to colitis in B6 mice, we determined if this treatment for 30 d (Expt 2) alters the gut microbiota structure and function in these mice. Compilation of OTU data generated from 16S rRNA sequences of fecal samples to different taxonomical levels showed that, compared with the pretreatment time point, abundances of major phyla changed significantly in YBG-fed mice but not in control mice (Figure 3A). YBG treatment resulted in an increase in the abundance of Bacteroidetes (P = 0.049) and Verrucomicrobia (mean ± SD: control = 7.8 ± 0.44 vs. YBG = 21.0 ± 9.6%; NS) phyla members and a decrease in Firmicutes (P < 0.001) and Proteobacteria (P < 0.001) in their fecal samples. Interestingly, at the genus level, abundances of many major microbial communities were altered significantly after YBG treatment (Figure 3B). Compared with the pretreatment time point, significant reductions in the abundance of microbial communities belonging to multiple genera, including Ruminococcus (phylum: Firmicutes; P = 0.003), Lactobacillus (phylum: Firmicutes; P = 0.02), Oscillospira (phylum: Firmicutes; P < 0.001), Dehalobacterium (phylum: Firmicutes; P < 0.006), and Odoribacter (phylum: Firmicutes; P < 0.001), were observed after YBG treatment. On the other hand, abundances of microbial communities belonging to many genera including Parabacteroidetes (phylum: Bacteroidetes; P < 0.005), Prevotella (phylum: Bacteroidetes; P < 0.002), Sutterella (phylum: Proteobacteria; P < 0.007), and Bifidobacterium (phylum: Actinobacteria; P = 0.048) were increased after YBG treatment. Interestingly, fecal samples collected after YBG treatment showed lower gut microbial α-diversity/species richness (P < 0.001) compared with the pretreatment time point (Supplemental Figure 5A). Further, β-diversity (Bray Curtis distance) analysis of fecal microbiota showed significant distance (P = 0.007) in the clustering/separation of samples collected before and after YBG treatment (Supplemental Figure 5B). As shown in Figure 3C, OTU-based prediction of metabolic functions of gut microbes revealed overrepresentation of many pathways, including that of carbohydrate metabolism (P = 0.031), glycan biosynthesis and metabolism (P = 0.027), and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (P = 0.01) in B6 mouse gut microbiota after YBG treatment compared with the pretreatment time point.

FIGURE 3.

Impact of oral administration of YBG on the composition of gut microbiota at the phylum level (A) and genus level (B) and predictive functions (C) in B6 mice (Expt 2). (A, B) OTU data of 16S rRNA gene sequences of fecal pellets collected before (day 0) and 30 d after treatment (day 30) were compiled to the phylum and genus levels based on the percentage identity to reference sequences (i.e., >97% identity). (B) A heatmap comparing day 0 and day 30 values of YBG-treated mice was generated using sequence counts of major genera (those with >1% of total sequences) that showed statistically significant differences. (C) OTU-biom data were used for predicting gene functional categories using the PICRUSt application, and the level 2 categories of the KEGG pathway that showed statistically significant differences are shown. n = 5 for both panels. *,**,***Different from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Expt, experiment; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; OTU, operational taxonomic unit; PICRUSt, Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

YBG treatment results in modulation of small and large intestinal immune phenotype in B6 mice

Since YBG treatment altered the gut microbiota and suppressed colitis susceptibility in B6 mice, we determined if YBG treatment alone has an impact on gut immune phenotype. Supplemental Figure 6 (Expt 2) shows that primarily the small intestine (ileum) but not the large intestine (colon) of mice that received YBG for 30 consecutive days expressed significantly higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα (P = 0.0039) and immune-regulatory enzyme Raldh1A2 (P = 0.001) compared with those of their untreated counterparts. On the other hand, significantly higher levels of IL10 expression were detected in both the ileum (P = 0.0017) and colon (P = 0.0042) of YBG-treated mice compared with controls. We then determined the T-cell phenotype of gut mucosa in mice that received YBG for 30 consecutive days by assessing the Foxp3+ T-cell frequencies and cytokine production (Expts 3 and 4). As shown in Supplemental Figure 7A and Figure 4A, significantly higher frequencies of Foxp3+ T cells were detected in MLNs (P = 0.016), SiLP (P = 0.0079), and LiLP (P = 0.0159) of YBG-treated mice compared with controls. Further, compared with those of controls, small intestinal cells from YBG-treated mice produced significantly higher amounts of IL10 (P = 0.016) and IL17 (P = 0.0044). On the other hand, colonic immune cells of YBG-treated mice produced higher amounts of IL10 (P = 0.0079), but not IL17 or IFNγ.

We then determined the influence of the microbiota on YBG consumption–associated immune modulation in B6 mice after depleting the gut bacteria using broad-spectrum antibiotics. As shown in Supplemental Figure 7B and Figure 4B, depletion of gut bacteria (Supplemental Figure 8) alone caused reduction in Foxp3+ T-cell frequencies in both control and YBG recipient mice, relative to their counterparts with intact microbiota (shown in Figure 4A). Further, SiLP cells, but not LiLP cells, from microbiota-depleted YBG recipient mice showed relatively higher frequencies of Foxp3+ T cells (P = 0.0041) compared with their control counterparts. On the other hand, small intestines of antibiotic-treated YBG-recipients showed higher IL10 (P = 0.0087), IL17 (P = 0.0159), and IFNγ (P = 0.041) production, compared with microbiota-depleted controls. Immune cells from large intestines of YBG-treated microbiota-depleted mice produced significantly higher amounts of IL17 (P = 0.0034) and IFNγ (P = 0.0039), but not IL10, compared with their control counterparts.

YBG treatment results in increased immune-regulatory SCFA production in B6 mice

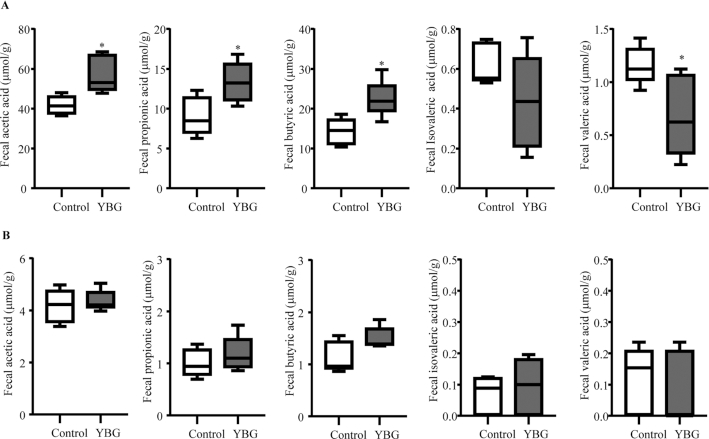

Since fermentation of nondigestible sugars by colonic bacteria can result in the generation of metabolites including SCFAs, fecal SCFA concentrations in control and YBG-treated B6 mice with intact and depleted gut microbiota (Expt 3) were determined. As observed in Figure 5A, significantly higher fecal acetic acid (P = 0.016), propionic acid (P = 0.026), and butyric acid (P = 0.013) and lower valeric acid (P = 0.036) concentrations were detected in YBG-treated mice compared with their control counterparts. On the other hand, depletion of gut microbiota not only resulted in the elimination of YBG treatment–associated effect on SCFA production but caused profound suppression of overall SCFA concentrations in both control and YBG-treated mice (Figure 5B) compared with those of mice with intact microbiota (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Impact of oral administration of YBG on the fecal SCFA concentrations in B6 mice with intact (A) and depleted (B) gut microbiota (Expt 3). (A, B) SCFA concentrations in fecal pellets collected from control and YBG-treated mice that were left alone or fed broad-spectrum antibiotics are shown. Values are means ± SDs (n = 5) for all panels. *Different from control, P < 0.05. Expt, experiment; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

YBG treatment–associated protection of B6 mice from colitis is gut microbe dependent

To determine if the YBG treatment–associated protection of B6 mice from colitis is microbiota dependent, YBG-treated and control B6 mice were given broad-spectrum antibiotics to deplete the gut microbiota and DSS to induce colitis (Expt 5) as depicted in Figure 6A. As shown in Figure 6B and C, control and YBG-treated mice with intact gut microbiota showed weight loss and disease severity comparable to that shown in Figure 1. Importantly, control mice with microbiota depletion showed relatively lesser weight loss and disease severity than their control counterparts, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.012) only at the 10-wk time point (Figure 6B; left panel). However, colon inflammation scores were not statistically significant in these mice (Figure 6C; left panel). On the other hand, YBG-treated, microbiota-depleted mice showed significantly greater weight loss and disease severity starting at the day 6 time point (P = 0.016), that were more severe thereafter (P < 0.01) compared with untreated mice with intact microbiota. Further, YBG-treated, microbiota-depleted mice showed greater colon inflammation (P = 0.047) compared with control mice (Figure 6C; right panel). Examination of cytokine profiles of immune cells from the colon revealed significantly higher production of proinflammatory IFNγ (P < 0.001) and IL17 (P < 0.001) and comparable anti-inflammatory IL10 production in YBG-treated, microbiota-depleted mice compared with YBG-treated mice with intact gut microbiota (Figure 6D). However, cells from microbiota-depleted control mice showed diminished IFNγ production compared with cells from controls with intact microbiota (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The literature suggests that certain CDPs such as BGs of different microbial and plant origin affect the host immune function (43–47). While previous studies using various BG preparations and BG-rich diets have shown that they have the ability to suppress gut inflammation in colitis models (10–14), others have shown that BGs aggravate colitis severity (15). Further, while it has been shown that genetic deletion of a BG interacting receptor, Dectin-1, does not affect the course of murine experimental colitis, another group found that Dectin-1 deficiency increased susceptibility to colitis (16, 17). Hence, although BGs from different sources can vary structurally and functionally (1), the true impact of orally administering BGs on gut inflammation and the mechanisms is unknown. The previously reported outcomes are nonconclusive without the use of well-defined, highly purified BGs such as the YBG used in this study. Here, we show that prolonged oral administration of a human dietary supplement-relevant dose of highly purified YBG, prior to DSS treatment–induced colitis, results in significantly lowered severity of gut inflammation in B6 mice. This diminished susceptibility to DSS colitis is associated with altered gut microbiota composition and function favoring polysaccharide metabolism, higher immune-regulatory SCFA production, and enhanced gut immune regulation.

Intriguingly, we found that treatment with highly purified YBG at the disease induction stage alone has no beneficial effects, but only prolonged oral pretreatment with this agent suppresses colitis susceptibility. This shows that well-defined BGs can promote protection from colitis, but this depends on gradually acquired enhanced immune regulation, perhaps mediated by altered/YBG-shaped gut microbiota. In fact, although the role of immune regulation promoted directly by YBG in the gut mucosa cannot be ruled out, we found that prolonged oral treatment using YBG causes changes in the gut microbial composition. YBG consumption resulted in reduced abundance of Firmicutes and increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia phyla, which include many polysaccharide fermenting bacteria (48, 49). However, YBG treatment also diminished the gut microbial diversity/species richness, suggesting that the YBG treatment–induced effect is due to selective enrichment of microbial communities that promote immune regulation, but not by increasing the diversity of gut microbiota. Further, predictive functional profiling of fecal microbiota showed overrepresentation of metabolic pathways linked to carbohydrate metabolism, glycan biosynthesis and metabolism, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites after YBG treatment compared with the pretreatment time point. More importantly, our novel observations that fecal concentrations of immune-regulatory microbial SCFAs (50, 51) such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid produced by gut microbiota are higher in YBG-treated mice suggest that an altered microbiota is functionally superior in terms of its ability to promote immune regulation. This notion has been validated by diminished SCFA concentrations, Treg frequencies in the gut mucosa, and elimination of the YBG treatment–induced effect upon depletion of the gut microbiota. Further, the need for prolonged pretreatment, which could potentially help gradual shaping of the gut microbiota structure and function, for protection from colitis is another indication that an altered gut microbiota is the key contributor of protection from colitis in YBG-fed mice.

Colonic microbial communities can ferment nondigestible dietary polysaccharides to use them as energy sources for their growth, and also produce small metabolites such as SCFAs that enhance gut immune regulation (16, 48, 50, 52-–57). Previous studies have shown that gut colonization by specific commensal microbial communities causes an induction and expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs in the intestinal and systemic compartments (58–60). Further, gut bacteria play a critical role in maintaining peripheral tolerance and gut immune homeostasis (61, 62). However, it is not known if BG-shaped gut microbes specifically promote Treg induction and/or expansion. Our observations that YBG treatment increases the production of microbial SCFAs, which are known to enhance gut integrity and immune regulation (50, 54), suggest that the microbiota does contribute to YBG treatment–associated increases in overall immune regulation. Importantly, abundances of microbes belonging to polysaccharide degrading as well as host beneficial communities such as Parabacteroides, Sutterella, Prevotella, Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia are increased upon prolonged YBG treatment. Moreover, microbial depletion and reduced SCFA production resulted in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines IFNγ and IL17 in the distal gut of YBG-treated mice, substantiating the notion that microbes contribute to enhanced immune regulation and diminished susceptibility to colitis when pretreated with this CDP.

Although this study is focused on the impact of YBG treatment on colitis susceptibility and distal gut, we also found that, unlike the large intestine, the small intestines of YBG-treated mice, with intact and depleted microbiota, have relatively higher frequencies of Tregs compared with untreated controls. This suggests that the YBG treatment–associated increase in Treg abundance in small and large intestinal compartments may involve different mechanisms. It is possible that, during prolonged treatment with YBG, at the employed human-relevant dose, YBG interacts directly with the small intestinal mucosa to enhance immune regulation and YBG treatment–associated enhanced immune regulation in the large intestine may be primarily microbiota (and SCFA) dependent. Of note, our recent report showed that treatment of mice with a higher dose of this YBG caused strong proinflammatory immune response in both the small and large intestine (29), suggesting that the use of higher doses of this CDP is not advisable to ameliorate the susceptibility to gut inflammation.

We previously reported that Dectin-1–dependent interaction of highly purified YBG with immune cells could promote a combination of both proinflammatory and immune-regulatory responses (19, 27) under normal circumstances. Our current study suggests that such a direct interaction can produce primarily pathogenic responses under depleted microbiota and proinflammatory conditions such as upon chemical insult using DSS. In fact, it has been shown that the degree and type of immune cell response to BGs depend on the cytokine milieu and microenvironment (63). It is possible that YBG is degraded by colonic bacteria to produce the immune-regulatory SCFAs, resulting in minimized direct interaction of this immune-stimulatory CDP with the large intestinal mucosa. On the other hand, microbial depletion could diminish YBG degradation and SCFA production. Further, DSS, which causes epithelial damage, can expose immune cells of the gut mucosa for direct interaction with YBG, resulting in dominant proinflammatory immune responses. This is evident from our observation that YBG-treated, microbiota-depleted mice present more severe colitis compared with YBG-treated mice having an intact microbiota and a control group of mice with intact and depleted microbiota.

Overall, although lessons learned from this study using a single dose of YBG in mouse models have limitations in terms of their clinical translation, we found that YBG can promote gut immune regulation by altering the gut microbiota, increasing SCFA production, and enhancing the overall immune regulation and gut health under normal circumstances, emphasizing the prebiotic value of BGs. Importantly, only preconditioning of the intestinal microenvironment by altering gut microbiota composition and function using YBG, which favors enhanced SCFA production and immune regulation, resulted in diminished susceptibility of B6 mice to colitis. We show that YBG treatment has no benefits in ameliorating the severity of ongoing gut inflammation, as in the case of UC. Hence, with respect to colitis, health benefits of YBG could be limited to those who are susceptible to, but have not yet developed, the disease rather than those who have established disease. We employed the microbiota depletion approach in our study primarily to understand the mechanism by which YBG treatment enhances the gut immune regulation and diminishes colitis susceptibility. Nevertheless, our observations suggest that consumption of YBG by those who are under antibiotic therapy could produce adverse effects such as gut inflammation. Of note, antibiotic treatments have been considered for ameliorating the severity of gut inflammation and for managing UC symptoms (64, 65). Our observations suggest the possibility that consumption of YBG, as a dietary supplement, by UC patients who are under such therapy will result in aggravated, rather than ameliorated, disease severity.

In conclusion, this study not only demonstrates the dietary supplement value of BGs in promoting gut health under normal conditions and the mechanisms but also highlights the limitations and potential adverse effects that these CDPs can induce under different conditions. Although it is possible that structurally distinct BGs could produce different outcomes, this study, which used a highly purified β-1,3/1,6-d-glucan, demonstrates that BGs may not be beneficial in suppressing ongoing gut inflammation and could produce adverse effects when used in combination with antibiotic therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—RG: researched and analyzed the data and edited the manuscript; RB, BJ, and JS researched and analyzed data; CV: designed experiments, researched and analyzed data, and wrote/reviewed/edited the manuscript and is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis; and all authors: read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

Supported by Medical University of South Carolina internal funds and NIH grants R21AI133798 (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), and R21AI133798 and R21AI136339-02S1 (Office of Dietary Supplements) administrative supplements (to CV).

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figures 1–8 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn.

RG, JS, RB, and BMJ contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used: B6 mice, C57BL/6 mice; BG, β-glucan; CDP, complex dietary polysaccharide; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; Expt, experiment; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LiLP, large intestinal lamina propria; MLN, mesenteric lymph node; MUSC, Medical University of South Carolina; OTU, operational taxonomic unit; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; SiLP, small intestinal lamina propria; STAMP, Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profile Package; Treg, regulatory T cell; UC, ulcerative colitis; YBG, yeast-derived β-glucan.

References

- 1. Synytsya A, Novak M. Structural analysis of glucans. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen J, Seviour R. Medicinal importance of fungal beta-(1→3), (1→6)-glucans. Mycol Res. 2007;111:635–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vannucci L, Krizan J, Sima P, Stakheev D, Caja F, Rajsiglova L, Horak V, Saieh M. Immunostimulatory properties and antitumor activities of glucans [Review]. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El Khoury D, Cuda C, Luhovyy BL, Anderson GH. Beta glucan: health benefits in obesity and metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:851362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mosikanon K, Arthan D, Kettawan A, Tungtrongchitr R, Prangthip P. Yeast beta-glucan modulates inflammation and waist circumference in overweight and obese subjects. J Diet Suppl. 2017;14:173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zou Y, Liao D, Huang H, Li T, Chi H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of beta-glucan consumption on glycemic control in hypercholesterolemic individuals. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2015;66:355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller R, Moore MV, Lewith G, Stuart BL, Ormiston RV, Fisk HL, Noakes PS, Calder PC. Yeast-derived beta-1,3/1,6 glucan, upper respiratory tract infection and innate immunity in older adults. Nutrition. 2017;39-40:30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McFarlin BK, Carpenter KC, Davidson T, McFarlin MA. Baker's yeast beta glucan supplementation increases salivary IgA and decreases cold/flu symptomatic days after intense exercise. J Diet Suppl. 2013;10:171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leentjens J, Quintin J, Gerretsen J, Kox M, Pickkers P, Netea MG. The effects of orally administered Beta-glucan on innate immune responses in humans, a randomized open-label intervention pilot-study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamiya T, Tang C, Kadoki M, Oshima K, Hattori M, Saijo S, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Iwakura Y. β-Glucans in food modify colonic microflora by inducing antimicrobial protein, calprotectin, in a Dectin-1-induced-IL-17F-dependent manner. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:763–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu B, Lin Q, Yang T, Zeng L, Shi L, Chen Y, Luo F. Oat β-glucan ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Food Funct. 2015;6:3454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung MY, Hwang JT, Kim JH, Shon DH, Kim HK. Sarcodon aspratus extract ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mouse colon and mesenteric lymph nodes. J Food Sci. 2016;81:H1301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun Y, Shi X, Zheng X, Nie S, Xu X. Inhibition of dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice by baker's yeast polysaccharides. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;207:371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou M, Wang Z, Chen J, Zhan Y, Wang T, Xia L, Wang S, Hua Z, Zhang J. Supplementation of the diet with Salecan attenuates the symptoms of colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heinsbroek SE, Williams DL, Welting O, Meijer SL, Gordon S, de Jonge WJ. Orally delivered β-glucans aggravate dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced intestinal inflammation. Nutr Res. 2015;35:1106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heinsbroek SE, Oei A, Roelofs JJ, Dhawan S, te Velde A, Gordon S, de Jonge WJ. Genetic deletion of dectin-1 does not affect the course of murine experimental colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, Brown J, Becker CA, Fleshner PR, Dubinsky M et al.. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. 2012;336:1314–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bacon JS, Farmer VC, Jones D, Taylor IF. The glucan components of the cell wall of baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) considered in relation to its ultrastructure. Biochem J. 1969;114:557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gudi R, Perez N, Johnson BM, Sofi MH, Brown R, Quan S, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Vasu C. Complex dietary polysaccharide modulates gut immune function and microbiota, and promotes protection from autoimmune diabetes. Immunology. 2019;157(1):70–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chevrier G, Mitchell PL, Rioux LE, Hasan F, Jin T, Roblet CR, Doyen A, Pilon G, St-Pierre P, Lavigne C et al.. Low-molecular-weight peptides from salmon protein prevent obesity-linked glucose intolerance, inflammation, and dyslipidemia in LDLR-/-/ApoB100/100 mice. J Nutr. 2015;145:1415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahler M, Bristol IJ, Leiter EH, Workman AE, Birkenmeier EH, Elson CO, Sundberg JP. Differential susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taghipour N, Molaei M, Mosaffa N, Rostami-Nejad M, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Anissian A, Azimzadeh P, Zali MR. An experimental model of colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium from acute progresses to chronicity in C57BL/6: correlation between conditions of mice and the environment. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eichele DD, Kharbanda KK. Dextran sodium sulfate colitis murine model: an indispensable tool for advancing our understanding of inflammatory bowel diseases pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6016–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DeVoss J, Diehl L. Murine models of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): challenges of modeling human disease. Toxicol Pathol. 2014;42:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dennehy KM, Ferwerda G, Faro-Trindade I, Pyz E, Willment JA, Taylor PR, Kerrigan A, Tsoni SV, Gordon S, Meyer-Wentrup F et al.. Syk kinase is required for collaborative cytokine production induced through Dectin-1 and Toll-like receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:500–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dennehy KM, Willment JA, Williams DL, Brown GD. Reciprocal regulation of IL-23 and IL-12 following co-activation of Dectin-1 and TLR signaling pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karumuthil-Melethil S, Gudi R, Johnson BM, Perez N, Vasu C. Fungal β-glucan, a Dectin-1 ligand, promotes protection from type 1 diabetes by inducing regulatory innate immune response. J Immunol. 2014;193:3308–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montufar-Solis D, Klein JR. An improved method for isolating intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) from the murine small intestine with consistently high purity. J Immunol Methods. 2006;308:251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gudi R, Perez N, Johnson BM, Sofi MH, Brown R, Quan S, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Vasu C. Complex dietary polysaccharide modulates gut immune function and microbiota, and promotes protection from autoimmune diabetes. Immunology. 2019;157:70–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sofi MH, Johnson BM, Gudi RR, Jolly A, Gaudreau MC, Vasu C. Polysaccharide A-dependent opposing effects of mucosal and systemic exposures to human gut commensal Bacteroides fragilis in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2019;68:1975–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Erben U, Loddenkemper C, Doerfel K, Spieckermann S, Haller D, Heimesaat MM, Zeitz M, Siegmund B, Kuhl AA. A guide to histomorphological evaluation of intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4557–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gudi RR, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Li G, Vasu C. Engineered dendritic cell-directed concurrent activation of multiple T cell inhibitory pathways induces robust immune tolerance. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson BM, Gaudreau MC, Al-Gadban MM, Gudi R, Vasu C. Impact of dietary deviation on disease progression and gut microbiome composition in lupus-prone SNF1 mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;181:323–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sofi MH, Gudi R, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Johnson BM, Vasu C. pH of drinking water influences the composition of gut microbiome and type 1 diabetes incidence. Diabetes. 2014;63:632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI et al.. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wixon J, Kell D. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes—KEGG. Yeast. 2000;17:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parks DH, Beiko RG. Identifying biologically relevant differences between metagenomic communities. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, Cuervo A, Arboleya S, Duranti S, Turroni F, Gonzalez S, Suarez A, Gueimonde M et al.. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. mBio. 2014;5:e01548–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang H, Liao X, Sparks JB, Luo XM. Dynamics of gut microbiota in autoimmune lupus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:7551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3123–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao G, Nyman M, Jonsson JA. Rapid determination of short-chain fatty acids in colonic contents and faeces of humans and rats by acidified water-extraction and direct-injection gas chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 2006;20:674–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dhariwal A, Chong J, Habib S, King IL, Agellon LB, Xia J. MicrobiomeAnalyst: a web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W180–W8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramberg JE, Nelson ED, Sinnott RA. Immunomodulatory dietary polysaccharides: a systematic review of the literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hong F, Yan J, Baran JT, Allendorf DJ, Hansen RD, Ostroff GR, Xing PX, Cheung NK, Ross GD. Mechanism by which orally administered beta-1,3-glucans enhance the tumoricidal activity of antitumor monoclonal antibodies in murine tumor models. J Immunol. 2004;173:797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suzuki I, Tanaka H, Kinoshita A, Oikawa S, Osawa M, Yadomae T. Effect of orally administered beta-glucan on macrophage function in mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1990;12:675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Suzuki I, Hashimoto K, Ohno N, Tanaka H, Yadomae T. Immunomodulation by orally administered beta-glucan in mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1989;11:761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Volman JJ, Ramakers JD, Plat J. Dietary modulation of immune function by beta-glucans. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P, Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:289–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez-Garcia M, Brazel DM, Swan BK, Arnosti C, Chain PS, Reitenga KG, Xie G, Poulton NJ, Lluesma Gomez M, Masland DE et al.. Capturing single cell genomes of active polysaccharide degraders: an unexpected contribution of Verrucomicrobia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marino E, Richards JL, McLeod KH, Stanley D, Yap YA, Knight J, McKenzie C, Kranich J, Oliveira AC, Rossello FJ et al.. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:552–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. D'Souza WN, Douangpanya J, Mu S, Jaeckel P, Zhang M, Maxwell JR, Rottman JB, Labitzke K, Willee A, Beckmann H et al.. Differing roles for short chain fatty acids and GPR43 agonism in the regulation of intestinal barrier function and immune responses. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Porter NT, Martens EC. The critical roles of polysaccharides in gut microbial ecology and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:349–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Temple MJ, Cuskin F, Basle A, Hickey N, Speciale G, Williams SJ, Gilbert HJ, Lowe EC. A Bacteroidetes locus dedicated to fungal 1,6-β-glucan degradation: unique substrate conformation drives specificity of the key endo-1,6-β-glucanase. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:10639–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Geirnaert A, Calatayud M, Grootaert C, Laukens D, Devriese S, Smagghe G, De Vos M, Boon N, Van de Wiele T. Butyrate-producing bacteria supplemented in vitro to Crohn's disease patient microbiota increased butyrate production and enhanced intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Turunen K, Tsouvelakidou E, Nomikos T, Mountzouris KC, Karamanolis D, Triantafillidis J, Kyriacou A. Impact of beta-glucan on the faecal microbiota of polypectomized patients: a pilot study. Anaerobe. 2011;17:403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carlson JL, Erickson JM, Hess JM, Gould TJ, Slavin JL. Prebiotic dietary fiber and gut health: comparing the in vitro fermentations of beta-glucan, inulin and xylooligosaccharide. Nutrients. 2017;9:E1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:172–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T et al.. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ye J, Qiu J, Bostick JW, Ueda A, Schjerven H, Li S, Jobin C, Chen ZE, Zhou L. The Aryl hydrocarbon receptor preferentially marks and promotes gut regulatory T cells. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2247–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46:562–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Steinmeyer S, Lee K, Jayaraman A, Alaniz RC. Microbiota metabolite regulation of host immune homeostasis: a mechanistic missing link. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Municio C, Alvarez Y, Montero O, Hugo E, Rodriguez M, Domingo E, Alonso S, Fernandez N, Crespo MS. The response of human macrophages to β-glucans depends on the inflammatory milieu. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nitzan O, Elias M, Peretz A, Saliba W. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1078–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Turner D, Levine A, Kolho KL, Shaoul R, Ledder O. Combination of oral antibiotics may be effective in severe pediatric ulcerative colitis: a preliminary report. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1464–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.