Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) may improve long-term multiple myeloma (MM) control through graft vs myeloma (GVM) effect. The BMT CTN 0102 was a biological assignment trial comparing tandem autologous transplant (auto-auto) vs. autologous followed by reduced intensity allogeneic (auto-allo) transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed MM with standard (N=625) or high-risk (beta 2 microglobulin at diagnosis ≥ 4 mg/dl or deletion of chromosome 13 by conventional karyotyping) disease (N=85). While the initial 3-year analysis showed no difference in progression-free survival (PFS) between arms in either risk group, we hypothesized that long-term follow-up may better capture the impact of GVM. Median follow-up of survivors is over 10 years. Among standard risk patients there was no difference in PFS (HR 1.11, 95% C.I. 0.93- 1.35, P=0.25) or OS (HR 1.03, 95% C.I. 0.82-1.28, P=0.82). The 6-year PFS was 25% in the auto-auto vs. 22% in auto-allo arm(P=0.32), and 6-year overall survival (OS) was 60% and 59% respectively (P=0.85). In the high-risk group, while there was no statistically significant difference in PFS (HR 0.66, 95% C.I. 0.41-1.07, P=0.07) and OS (HR 1.01, 95% C.I. 0.60-1.71, P=0.96), a reduction in 6-year risk of relapse, 77% vs. 47% (P= 0.005), was reflected in better PFS, 13% vs. 31% (P=0.05), but similar OS, 47% vs. 51% (P=0.69). Allogeneic HCT can lead to long-term disease control in patients with high risk MM and needs to be explored in the context of modern therapy.

Keywords: Multiple Myeloma, Transplantation, Allogeneic, Transplantation, Autologous

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease characterized by malignant plasma cell proliferation, bone destruction and immunodeficiency. Median age at diagnosis is approximately 70 years. Conventional treatment includes induction therapy with combinations of proteasome inhibitors, immune-modulatory drugs (IMiDs) and steroids with or without alkylating agents. More than 80% of patients will have at least a 50% reduction in tumor burden (PR) with up to 15% of patients achieving a complete remission (CR)1–4 with induction therapy. In younger patients (less than 65 years of age or fit patients over the age of 65) high dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is frequently performed as consolidation therapy, increasing the rates of complete remission to 50-60%5–9. Median remission duration for patients undergoing autologous HCT without subsequent therapy is approximately 24-30 months without maintenance therapy and 48 to 57 months with maintenance lenalidomide10–12

A variety of strategies have been studied to increase remission duration after autologous HCT including post HCT consolidation through tandem transplantation with either an autologous or an allogeneic HCT 13–25 or post-transplant maintenance and consolidation therapy5, 10, 26–32. Post HCT consolidation with an allogeneic HCT has the theoretical advantage of exploiting a graft versus myeloma effect33–35, but data from prospective trials has been equivocal13–15, 18, 22–25. In 2003 the Blood and Marrow Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) embarked on a large prospective trial comparing transplant outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed MM who after a conventional single autologous transplant with high dose melphalan were biologically assigned to receive either a second autologous HCT or a reduced intensity allogeneic HCT, depending on the presence or absence of a fully HLA matched sibling donor (BMT CTN-0102),36. The primary endpoint of the trial was progression free survival (PFS) at 3 years for patients considered at standard risk for relapse based on their beta 2 microglobulin (B2M) at the time of diagnosis or the presence of deletion 13 by conventional karyotypic analysis (both known poor prognostic factors at the time of study design)22.

At the time of initial report, the 3-year PFS of the 635 patients with standard risk disease was 43% (95% CI 36–51) in the auto-allo arm and 46% (95% CI 42–51) in the auto-auto arm (p=0. 671); overall survival (OS) also did not differ at 3 years (77% [95% CI 72–84] vs 80% [77–84]; p=0.191). For patients with high risk disease, 3 year PFS was 40% (95%CI 27-60) in the auto-allo arm and 33% (95%CI 22-50) in the auto-auto arm (p=0.743); OS was 59% (95%CI 45-78) in the auto-allo arm compared to 67% (95%CI 54-82) in the auto-auto arm (p=0.460). The median follow up at the time of initial publication was 40 months. With longer follow up, it was possible that the reduced risk of relapse in the auto-allo arm would exceed the higher non relapse mortality (NRM). Therefore, we performed updated analysis of primary and secondary endpoint to assess whether the initial conclusions are still valid.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Characteristics

The study has been described in detail in the primary publication22. In brief, BMT CTN-0102 was a phase III multicenter trial with biologic treatment arm assignment. The trial was conducted in 37 transplant centers of the BMT CTN. Patients who met eligibility criteria underwent HLA typing and related donor search and were assigned to the auto-allo treatment arm if an HLA-matched sibling donor was identified36. Treatment assignment occurred when donor availability status was confirmed; this could occur at any time from enrollment up to 30 days after the first autologous HCT. Those without a suitable sibling donor were assigned to the auto-auto arm. Patients were classified as having high-risk disease if their serum B2M was ≥ 4·0 mg/L or if deletion of chromosome 13 was detected by metaphase karyotyping.

Enrolled patients received melphalan 200mg/m2 (Mel200) followed by autologous peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) infusion 48 hours later. At least 60 days after recovery of the first autologous HCT, patients received a second HCT, according to treatment arm. Those assigned to auto-allo received 200 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI) followed by allogeneic hematopoietic progenitor cells infusion. The target cell dose for allografts was 2·0 x106 CD34+ cells/kg. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). MMF was discontinued on day +28 after allogeneic HCT. In patients without active GVHD, cyclosporine was tapered starting at day +84. Patients without an HLA-matched sibling donor received a second autologous HCT with Mel200 conditioning. Patients assigned to the auto-auto arm were randomized to receive either no further therapy or thalidomide plus dexamethasone for 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

Primary endpoint was PFS and secondary endpoints were OS, NRM and relapse. The definition of disease response utilized the international uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma 37 with the addition of a category of near complete response (nCR), defined as evidence of disease by immunofixation electrophoresis without morphologic evidence of bone marrow involvement by myeloma. Disease assessments were performed prior to first autologous HCT, at time of second transplantation, and after second transplantation at eight weeks, six months, and every six months up to three years. After three years, patients were followed through the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research follow up forms periodically per standard procedure. More than 90% of all forms expected were completed at the time of this analysis and the current dataset was frozen in June 2018.

Primary analysis was performed using the intent-to-treat principle, i.e., patients were classified according to their original assigned treatment, even if they did not receive all prescribed interventions. All outcomes were measured from the time of first autologous HCT.

Survival distributions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, while NRM, relapse/progression, acute and chronic GVHD were estimated using cumulative incidence. For this updated analysis, arms were compared using point wise differences in survival and Gray’s test38 or log-rank test39 for PFS and OS outcomes and Gray’s test38 in cumulative incidence of competing events (NRM and Relapse). Point wise estimates are reported at 6 years (double of primary endpoint) and 10 years (approximate median duration of follow up of survivors).

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1 according to assigned treatment arm and risk category. Median follow up of survivors is 124 months (range 2-161 months) for standard risk and 146 months (range 5-168 months) for high-risk patients.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics According to Treatment Arm and Risk Group.

| Standard risk | High Risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Auto-auto N (%) | Auto-allo N(%) | Total N(%) | Auto-auto N (%) | Auto-allo N (%) | Total N(%) |

| Number of patients | 436 | 189 | 625 | 48 | 37 | 85 |

| Sex (male) | 260 (60) | 111 (59) | 371 (59) | 27 (56) | 21 (57) | 48 (56) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 335 (77) | 161 (85) | 496 (79) | 38 (79) | 33 (89) | 71 (84) |

| Black | 77 (18) | 18 (10) | 95 (15) | 8 (17) | 3 (8) | 11(13) |

| Other | 24 (6 | 10 (5) | 34 (6) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 18 (4) | 15 (8) | 33(5) | 3 (6) | 4 (11) | 7 (8) |

| Age | ||||||

| Median(range) | 55 (23-71) | 53 (29-68) | 55 (23-71) | 57 (32-71) | 51 (32-66) | 55 (32-71) |

| >=60 | 117 (27) | 28 (15) | 143 (23) | 14 (29) | 4(11) | 18 (21) |

| Stage at Diagnosis | ||||||

| Stage I/II | 436 (100) | 189 (100) | 625 (100) | 40(83) | 33 (89) | 73 (86) |

| Beta 2 Microglobulin > 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42 (88) | 20 (54) | 62 (73) |

| Deletion 13 Present | 1 (<1) | 4 (2) | 5 (<1) | 5 (10) | 12 (32) | 17 (20) |

| Karnofsky score | ||||||

| >=90 | 262 (60) | 121 (64) | 383 (61) | 25 (52) | 24 (65) | 49 (58) |

| <90 | 102 (23) | 44 (23) | 146 (23) | 17 (35) | 9 (24) | 26 (31) |

| Missing | 72 (17) | 24 (13) | 96 (15) | 6 (13) | 4 (11) | 10 (12) |

| Type of Induction Therapy | ||||||

| VAD based | 113 (26) | 36 (19) | 149 (24) | 15 (31) | 8 (22) | 23 (27) |

| Thalidomide based | 258 (59) | 114 (60) | 372 (60) | 19 (40) | 21 (57) | 40 (47) |

| Bortezomib based | 39 (9) | 26 (14) | 65 (10) | 10 (21) | 7 (19) | 17 (20) |

| Other | 15 (3) | 6 (3) | 21 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Missing | 11 (3) | 7 (4) | 18 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Disease Status at Registration | ||||||

| CR/nCR | 106 (24) | 46 (25) | 152 (24) | 2 (4) | 5 (13) | 7 (8) |

| VGPR | 79 (18) | 32 (17) | 111 (18) | 1 (2) | 7 (19) | 8 (9) |

| PR | 158 (36) | 76 (40) | 234 (37) | 21 (44) | 14 (38) | 35 (41) |

| MR/SD | 52 (12) | 23 (12) | 75 (12) | 16 (34) | 7 (19) | 23 (26) |

| Unknown | 41 (9) | 12 (6) | 53 (8) | 8 (17) | 4 (11) | 12 (14) |

| Median Time Dx to HCT #1 | 7 (<1-232) | 7 (<1-34) | 7 (<1-232) | 7 (5-22) | 7 (3-38) | 7 (3-38) |

| Actual Treatment Given | ||||||

| Tandem Auto + Thal/Dex | 179 (41) | 0 | 179 (29) | 16 (33) | 0 | 16 (19) |

| Tandem Auto + No Maintenance | 187 (43) | 0 | 187 (30) | 15 (31) | 0 | 15 (18) |

| Auto/Allo | 0 | 156 (83) | 156 (25) | 0 | 29 (78) | 29 (34) |

| Single Auto | 69 (16) | 33 (17) | 102 (16) | 17 (35) | 8 (22) | 25 (29) |

| No transplant | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 124 (2-161) | 124 (8-153) | 124 (2-161) | 134 (5-168) | 148 (88-152) | 146 (5-168) |

Progression Free and Overall Survival

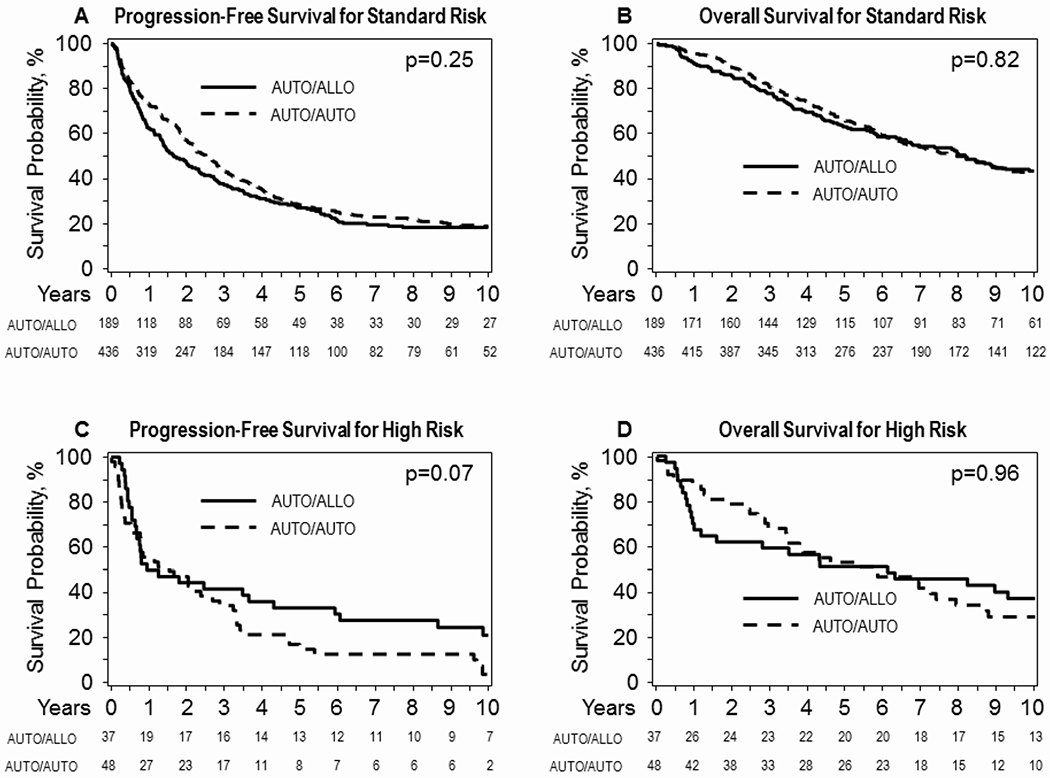

In the standard risk group (Figure 1A), there was no statistically significant difference between the two arms in PFS (HR 1.11, 95% C.I. 0.93- 1.35, P=0.25). The 6-year PFS was 25% (95% CI 21-30) in the auto-auto arm vs. 22% (95%CI 16-28) in the auto-allo arm (p=0.32). There was also no statistically significant difference between treatment arms in OS (HR 1.03, 95% C.I. 0.82-1.28, P=0.82)(Figure 1B). The 6-year OS rate was 60% (95% CI 55-64%) versus 59% (95% CI 52-66%) in the auto-auto and auto-allo arms respectively (P=0.85). At 10 years the PFS and OS in the auto-auto and auto-allo arms also did not show statistically significant differences 19% (95% CI 15-23) versus 18% (95% CI 13-25) for PFS (P=0.87) and 43% (95% CI 38-48) and 44% (95% Ci 36-51) for OS respectively (P=0.91).

Figure 1-.

Long-term progression-free survival (panel 1A) and overall survival (panel 1B) for standard risk patients and high-risk patients (panels 1C and 1D respectively) according to biologically assigned treatment arm and utilizing intent to treat principle.

In the high-risk group (figure 1C), the difference between auto-auto and auto-allo arms was not statistically significant (HR 0.66, 95% C.I. 0.41-1.07, P=0.07). The PFS at 6 and 10 years were 13% (95% CI 5-24) and 4% (95%CI 0-13) for the auto-auto arm versus 31% (95% CI 17-46) and 21% (95% CI 9-31) for the auto-allo arm. These differences were statistically significant at each time point (Figure 1C, P=0.05 and 0.03 respectively). OS was not different between the two arms (HR 1.01, 95% C.I. 0.60-1.71, P=0.96). The 6 and 10-year OS were 47% (95% CI 33-61) and 29% (95% CI 17-44) for the auto-auto arm and 51% (95%CI 35-67) and 37% (95% CI 23-53) for the auto-allo arm (Figure 1D, P=0.69 and P=0.45 respectively). Supplementary Table 1 displays yearly rates of PFS, OS, NRM and relapse.

Non-Relapse Mortality

The 6-and 10 year NRM rate for patients in the standard risk group was 9% (95% CI 7-12) and 11% (95% CI 8-14) respectively in the auto-auto vs. 20% and 20% (95% CI 14-26) in auto-allo arm (Figure 2A, P <0.001). For patients with high-risk disease NRM at 6 and 10 years was 11% (95% CI 4-21) and 11% (95% CI 4-21) in the auto-auto arm vs. 22% (95% CI 10-37) and 22% (95% CI 10-37) in the auto-allo arm (Figure 2C, P=0.17). Table 2 summarizes causes of death according to treatment arm. Although primary disease was the main cause of death in both arms, other causes of death (i.e infections, organ failure and GVHD) contributed to a numerically higher proportion of deaths in the auto-allo arm.

Figure 2-.

Long term risk of non-relapse mortality (panel 2A) and disease relapse/progression (panel 2B) for standard risk patients, non-relapse mortality (panel 2C) and disease relapse/progression (panel 2D) for high risk patients according to biologically assigned treatment arm and utilizing intent to treat principle.

Table 2:

Cause of death According to risk strata and treatment arm

| Standard risk | High risk | All patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | Auto-auto N (%) | Auto-allo N(%) | Auto-auto N (%) | Auto-allo N(%) | Auto-auto N (%) | Auto-allo N(%) |

| Number of patients | 436 | 189 | 48 | 37 | 484 | 226 |

| Number of deaths | 240 | 106 | 32 | 26 | 272 | 132 |

| Cause of death | ||||||

| Primary disease | 188 (78) | 59 (56) | 21 (66) | 16 (61) | 209 (77) | 75 (57) |

| New malignancy | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (4) | 4 (1) | 3 (2) |

| GVHD | 3 (2) | 6 (6) | 0 | 2 (8) | 3 (1) | 8 (6) |

| Infection | 10 (4) | 10 (10) | 4 (13) | 0 | 14 (5) | 10 (8) |

| Organ failure | 11 (5) | 12 (13) | 4 (13) | 3 (12) | 15 (6) | 17 (13) |

| Other | 21 (9) | 11 (10) | 3 (9) | 4 (15) | 24 (9) | 15 (11) |

| Unknown | 3 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) | 4 (3) |

Relapse and Evidence of Graft vs Myeloma Effect

In patients with standard risk disease the risk of relapse at 6 and 10 years was 66% (95% CI 61-70) and 70% (95% CI 66-75) in the auto-auto and 59% (95% CI 52-66) and 62% (95% CI 55-69%) in the auto-allo arm (Figure 2B, P=0.12 and P=0.05 respectively). In contrast, although the number of patients at risk was small, high-risk patients in the auto-auto arm had higher risk of relapse than patients in the auto-allo arm at both 6 years 77% (95% CI 64-87) versus 47% (95% CI 31-63) (p=0.005) and 10 years 86% (95% CI 73-94) versus 57% (95% CI 40-72) (Figure 2D, P=0.004).

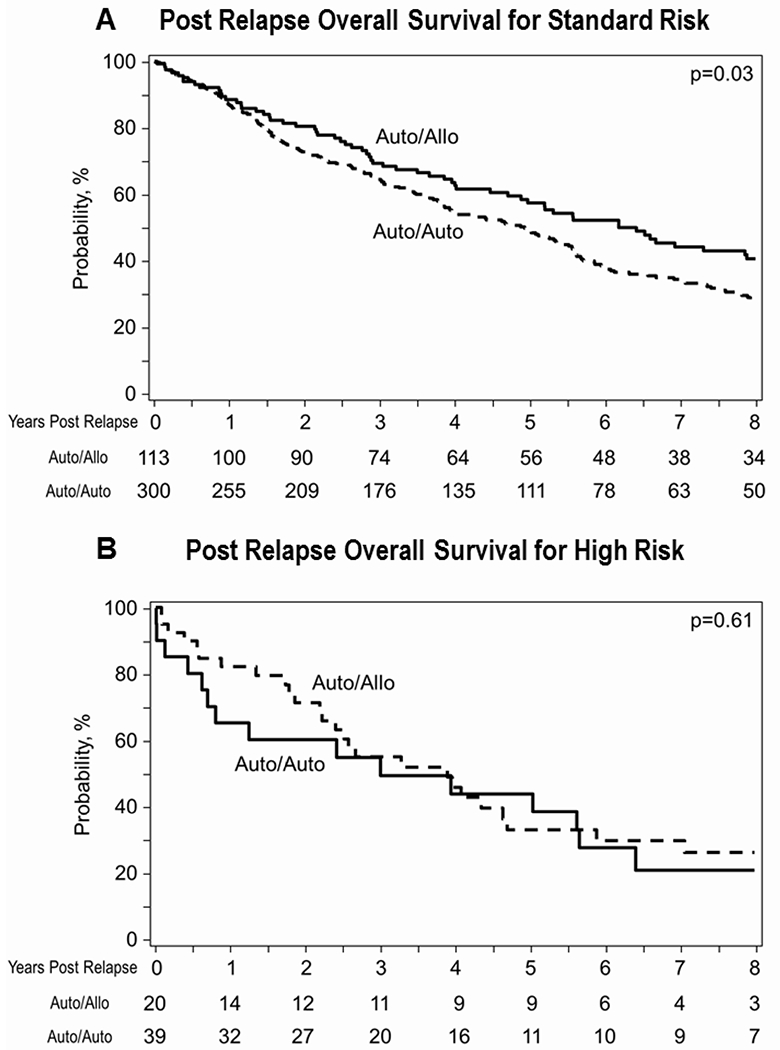

Given the prior observation that recipients of allogeneic transplantation may have better OS after relapse23, 40, 41, we compared post relapse OS between auto-auto and auto-allo arms. In the standard risk group, post relapse OS was superior in the auto-allo arm (P=0.03 while no statistically significant difference between arms was noted in the high-risk group (0.61, Figure 3)

Figure 3-.

Post relapse/progression overall survival for standard-risk (panel 3A) and high-risk patients (panel 3B).

Discussion

BMT CTN-0102 is the largest study performed comparing auto-auto vs. auto-allo transplantation in the initial management of patients with MM. The initial report with median follow -up of 40 months demonstrated higher rate of CR in the auto-allo arm and no difference in PFS and OS22. The present long-term follow-up update indicates that among patients with high-risk MM, the significant reduction in risk of relapse with auto-allo may surpass the impact of higher NRM and lead to better long term PFS.

Fifteen years have passed since the first patient was accrued to BMT CTN 0102. The field of myeloma therapy has since undergone major changes including the establishment of post auto HCT maintenance therapy as standard of care12, definition of triplet regimens as optimal induction therapies 42 and long-term benefit of maintenance therapy10–12. Other changes in the field include the approval of new agents and combinations as effective salvage therapies such as carfilzomib-based, pomalidomide-based and monoclonal antibody-based combinations that have extended survival after failure of primary therapy43,44. Myeloma investigators have also established minimal residual disease negativity at a sensitivity of 10−5 either by multi parameter flow or next generation sequencing as an important predictor for long term disease control and survival regardless of treatment45, 46, and reaffirmed the continued benefit of high dose melphalan and autologous HCT support as consolidation therapy for initial induction treatment47, 48. More recently, interest in tandem autologous transplant has increased given the evidence that it may benefit particularly patients with high-risk myeloma49. Yet despite these advances, most patients with myeloma will have disease recurrence and die from their disease.

At the time when BMT CTN 0102 was performed the role of upfront allogeneic HCT consolidation was viewed as one of the most important questions to explore according to many experts50. The primary results of BMT CTN 0102 together with the above observations have led to the commonly held practice that allogeneic HCT should not be considered as standard of care for upfront therapy of standard risk myeloma patients and its role as salvage therapy is still disputed51, 52. Importantly, the substantial changes in risk stratification occurring since BMT CTN 0102 was designed make findings difficult to extrapolate to patients currently considered high risk based on FISH, β2-microglobulin and LDH53, 54.

Due to the significant differences in both real and perceived toxicities between allogeneic HCT and other treatment modalities, comparing allogeneic transplantation to alternative treatments has been a challenge. A randomized trial of allogeneic HCT versus an alternative treatment among patients with an appropriate donor could provide the definitive answer to the role of allogeneic transplantation either as upfront or salvage therapy for myeloma. With the advent of post-transplant cyclophosphamide and the successful use of mismatched related or unrelated HCT55, 56, such a trial is now feasible but difficult to perform. In fact, a recent trial exploring allogeneic transplantation and post-transplant ixazomib maintenance in high-risk myeloma (BMT CTN 1302) closed prematurely due to poor accrual.

The results presented here should underscore the potential therapeutic effects of allogeneic HCT in myeloma particularly in patients with high-risk disease, although that patient subset was relatively small with some heterogeneity between the arms in terms of β2-microglobulin at diagnosis, induction treatment received and disease control prior to transplantation. The long-term results of BMT CTN 0102, including the improved OS after relapse for standard risk-patients in the auto-allo arm, clearly demonstrate a durable graft versus myeloma effect since the anti-myeloma effect of 200 cGy of TBI is negligible. Indeed, one of the major criticisms of the study design was not having used a more intense conditioning for the allogeneic HCT arm such as fludarabine/melphalan combinations57. The observation of better post relapse OS in patients who received allogeneic transplant supports that these patients do not derive less benefit from drugs that have been introduced in the MM therapeutic landscape in the last decade, confirming prior findings40, 58.

The present study also demonstrates the limited effect of GVM and the need to further enhance disease control post allograft through maintenance strategies since the risk of relapse is still substantial and the reduction in relapse risk after auto-allo is only evident after year 4 in the high-risk group and even later in the standard risk group. Lenalidomide maintenance post allogeneic HCT in myeloma has been shown to be associated with increased risks of GVHD at standard doses but lower doses may be better tolerated and still associated with an antitumor effect59. Many other relapse prevention strategies have yet to be prospectively explored in the setting of allogeneic HCT including monoclonal antibodies, proteasome inhibitors, and other IMIDs such as pomalidomide.

In this study as in others, the benefit accrued by relapse reduction with allogeneic HCT is counterbalanced by a twofold increase in overall NRM (20% vs 10% in standard risk disease). More effective GVHD prevention strategies (i.e post-transplant cyclophosphamide55,56,60 and CD34 selection61) together with improved infectious prophylaxis as well as continued advances in supportive care could continue to reduce the morbidity and mortality of allogeneic transplantation in myeloma. This should motivate the field to continue to explore this therapeutic modality in carefully designed prospective clinical trials.

The use of autologous anti-BCMA CAR-T cells has been shown to be extremely effective in inducing rapid and profound remissions in patients with multiply relapsed myeloma refractory to IMID and PIs 62. Although it is tempting to believe that earlier use of BCMA CAR T cell therapy could abrogate the need for allogeneic transplantation in a substantial proportion of patients, studies of early use of CAR therapies for myeloma have not yet been reported. Given the improvement in post-transplant survival seen in the present study, it is reasonable to hypothesize that CAR T cell therapies as well as other immune-therapeutic maneuvers will be more effective and result in more long term remissions when done in the context of an allogeneic HCT63.

With the advent of post-transplant cyclophosphamide that allows for use of less than perfectly matched HLA donors without an excessive risk of NRM it is now likely that near all relapsed myeloma patients under the age of 65 will have a donor for an allogeneic HCT. We hope that the results presented here will encourage both manufacturers and investigators to explore the role of post allogeneic HCT CAR T cell therapies which have been shown to be safe and effective in the context of CD19 + acute lymphoblastic leukemia64, 65 and non-Hodgkin lymphoma66, 67.

In summary, when initially reported, the data from BMT CTN-0102 demonstrated that an allogeneic HCT did not confer improvements in PFS or OS in patients with standard or high-risk disease. Over time, there was substantial reduction in risk of relapse in the auto-allo arm that was statistically significant at 6 and remains statistically significant at 10 years in the high-risk group, further supporting the existence of clinically significant graft versus myeloma effect. Although these findings do not endorse auto-allo tandem transplantation as an upfront strategy for most patients with MM, they do indicate that in a subset of patients, graft versus myeloma effect can provide long-term control of high-risk disease. The upfront identification of what patients would derive most benefit from allogeneic transplantation remain one of the greatest challenges in MM.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Long-term follow up of auto-auto vs. auto-allo in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma confirm significant and durable reduction in risk of relapse with auto-allo approach.

Auto-allo transplantation is associated with better 6-year PFS for high-risk patients.

Patients who relapse after auto-allo have longer post-relapse survival than patients who relapse after auto-auto transplant.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Support for this study was provided to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network by grant #U01HL069294 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, along with funding from the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG grant award U10CA180888). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or SWOG. The Clinicaltrials.gov identifier is NCT00075829.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, Rajkumar SV, Epstein J, Kahanic SP, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017. February 04; 389(10068): 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakubowiak AJ, Dytfeld D, Griffith KA, Lebovic D, Vesole DH, Jagannath S, et al. A phase 1/2 study of carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone as a frontline treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood 2012. August 30; 120(9): 1801–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, Petrucci MT, Pantani L, Galli M, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet 2010. December 18; 376(9758): 2075–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson PG, Hari P, Callander N, Noga SJ, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood 2012. May 10; 119(19): 4375–4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, Di Raimondo F, Ben Yehuda D, Petrucci MT, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014. September 04; 371(10): 895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, Conticello C, Catalano L, Corradini P, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015. December; 16(16): 1617–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Owen RG, Bell SE, Hawkins K, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2003. May 8; 348(19): 1875–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fermand JP, Ravaud P, Chevret S, Divine M, Leblond V, Belanger C, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: up-front or rescue treatment? Results of a multicenter sequential randomized clinical trial. Blood 1998. November 1; 92(9): 3131–3136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, Montefusco V, Conticello C, Musto P, et al. Autologous transplant vs oral chemotherapy and lenalidomide in newly diagnosed young myeloma patients: a pooled analysis. Leukemia 2017. January 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, Richardson PG, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012. May 10; 366(19): 1770–1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holstein SA, Jung SH, Richardson PG, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, et al. Updated analysis of CALGB (Alliance) 100104 assessing lenalidomide versus placebo maintenance after single autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 2017. September; 4(9): e431–e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, Richardson PG, Hulin C, Tosi P, et al. Lenalidomide Maintenance After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017. October 10; 35(29): 3279–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorkstrand B, Iacobelli S, Hegenbart U, Gruber A, Greinix H, Volin L, et al. Tandem autologous/reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem-cell transplantation versus autologous transplantation in myeloma: long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2011. August 1; 29(22): 3016–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garban F, Attal M, Michallet M, Hulin C, Bourhis JH, Yakoub-Agha I, et al. Prospective comparison of autologous stem cell transplantation followed by dose-reduced allograft (IFM99-03 trial) with tandem autologous stem cell transplantation (IFM99-04 trial) in high-risk de novo multiple myeloma. Blood 2006. May 1; 107(9): 3474–3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knop S, Liebisch P, Hebart H, Holler E, Engelhardt M, Bargou RC, et al. Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant Versus Tandem High-Dose Melphalan for Front-Line Treatment of Deletion 13q14 Myeloma - An Interim Analysis of the German DSMM V Trial. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2009. November 20, 2009; 114(22): 51-. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mai EK, Benner A, Bertsch U, Brossart P, Hanel A, Kunzmann V, et al. Single versus tandem high-dose melphalan followed by autologous blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: long-term results from the phase III GMMG-HD2 trial. Br J Haematol 2016. June; 173(5): 731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau P, Hullin C, Garban F, Yakoub-Agha I, Benboubker L, Attal M, et al. Tandem autologous stem cell transplantation in high-risk de novo multiple myeloma: final results of the prospective and randomized IFM 99-04 protocol. Blood 2006. January 1; 107(1): 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosinol L, Perez-Simon JA, Sureda A, de la Rubia J, de Arriba F, Lahuerta JJ, et al. A prospective PETHEMA study of tandem autologous transplantation versus autograft followed by reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2008. November 1; 112(9): 3591–3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Facon T, Guilhot F, Doyen C, Fuzibet JG, et al. Single versus double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2003. December 25; 349(26): 2495–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavo M, Tosi P, Zamagni E, Cellini C, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Prospective, randomized study of single compared with double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: Bologna 96 clinical study. J Clin Oncol 2007. June 10; 25(17): 2434–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreau P, Garban F, Attal M, Michallet M, Marit G, Hulin C, et al. Long-term follow-up results of IFM99-03 and IFM99-04 trials comparing nonmyeloablative allotransplantation with autologous transplantation in high-risk de novo multiple myeloma. Blood 2008. November 1; 112(9): 3914–3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan A, Pasquini MC, Logan B, Stadtmauer EA, Vesole DH, Alyea E 3rd, et al. Autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation followed by allogeneic or autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma (BMT CTN 0102): a phase 3 biological assignment trial. Lancet Oncol 2011. December; 12(13): 1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gahrton G, Iacobelli S, Bjorkstrand B, Hegenbart U, Gruber A, Greinix H, et al. Autologous/reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation vs autologous transplantation in multiple myeloma: long-term results of the EBMT-NMAM2000 study. Blood 2013. June 20; 121(25): 5055–5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruno B, Rotta M, Patriarca F, Mordini N, Allione B, Carnevale-Schianca F, et al. A comparison of allografting with autografting for newly diagnosed myeloma. N Engl J Med 2007. March 15; 356(11): 1110–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giaccone L, Storer B, Patriarca F, Rotta M, Sorasio R, Allione B, et al. Long-term follow-up of a comparison of nonmyeloablative allografting with autografting for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood 2011. June 16; 117(24): 6721–6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, Doyen C, Hulin C, Benboubker L, et al. Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood 2006. November 15; 108(10): 3289–3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, Caillot D, Moreau P, Facon T, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012. May 10; 366(19): 1782–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig H, Durie BG, McCarthy P, Palumbo A, San Miguel J, Barlogie B, et al. IMWG consensus on maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood 2012. March 29; 119(13): 3003–3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan GJ, Gregory WM, Davies FE, Bell SE, Szubert AJ, Brown JM, et al. The role of maintenance thalidomide therapy in multiple myeloma: MRC Myeloma IX results and meta-analysis. Blood 2012. January 05; 119(1): 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlogie B, Tricot G, Anaissie E, Shaughnessy J, Rasmussen E, van Rhee F, et al. Thalidomide and hematopoietic-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2006. March 09; 354(10): 1021–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt B, El Jarari L, Bertsch U, Salwender H, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/ GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol 2012. August 20; 30(24): 2946–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosinol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, de la Guia AL, Blanchard M, de la Rubia J, et al. Bortezomib and thalidomide maintenance after stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a PETHEMA/GEM trial. Leukemia 2017. February 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tricot G, Vesole DH, Jagannath S, Hilton J, Munshi N, Barlogie B. Graft-versus-myeloma effect: proof of principle. Blood 1996. February 01; 87(3): 1196–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lokhorst HM, Schattenberg A, Cornelissen JJ, van Oers MH, Fibbe W, Russell I, et al. Donor lymphocyte infusions for relapsed multiple myeloma after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: predictive factors for response and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol 2000. August; 18(16): 3031–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroger N, Schwerdtfeger R, Kiehl M, Sayer HG, Renges H, Zabelina T, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation followed by a dose-reduced allograft induces high complete remission rate in multiple myeloma. Blood 2002. August 1; 100(3): 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logan B, Leifer E, Bredeson C, Horowitz M, Ewell M, Carter S, et al. Use of biological assignment in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation clinical trials. Clin Trials 2008; 5(6): 607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006. September; 20(9): 1467–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray RJ. A Class of $K$-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Ann Statist 1988. 1988/09; 16(3): 1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Q, Sun J. Generalized log-rank test for mixed interval-censored failure time data. Stat Med 2004. May 30; 23(10): 1621–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Htut M, D’Souza A, Krishnan A, Bruno B, Zhang MJ, Fei M, et al. Autologous/Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation versus Tandem Autologous Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma: Comparison of Long-Term Postrelapse Survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018. March; 24(3): 478–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maffini E, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, Bruno B, Sahebi F, Shizuru JA, et al. Long-term follow up of tandem autologous-allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2019. February; 104(2): 380–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar SK, Callander NS, Alsina M, Atanackovic D, Biermann JS, Castillo J, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018. January; 16(1): 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimopoulos MA, Kaufman JL, White D, Cook G, Rizzo M, Xu Y, et al. A Comparison of the Efficacy of Immunomodulatory-containing Regimens in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: A Network Meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2018. March; 18(3): 163–173 e166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maiese EM, Ainsworth C, Le Moine JG, Ahdesmaki O, Bell J, Hawe E. Comparative Efficacy of Treatments for Previously Treated Multiple Myeloma: A Systematic Literature Review and Network Meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2018. March; 40(3): 480–494 e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC, Owen RG, Child JA, Thakurta A, et al. Association of Minimal Residual Disease With Superior Survival Outcomes in Patients With Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2017. January 1; 3(1): 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perrot A, Lauwers-Cances V, Corre J, Robillard N, Hulin C, Chretien ML, et al. Minimal residual disease negativity using deep sequencing is a major prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood 2018. December 6; 132(23): 2456–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, Leleu X, Caillot D, Escoffre M, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2017. April 06; 376(14): 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar SK, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Terpos E, Nahi H, Goldschmidt H, et al. Natural history of relapsed myeloma, refractory to immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors: a multicenter IMWG study. Leukemia 2017. November; 31(11): 2443–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavo M, Goldschmidt H, Rosinol L, Pantani L, Zweegman S, Salwender HJ, et al. Double Vs Single Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Long-Term Follow-up (10-Years) Analysis of Randomized Phase 3 Studies. Blood 2018; 132(Supplement 1): 124–124. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrara JL, Anasetti C, Stadtmauer E, Antin J, Wingard J, Lee S, et al. Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network State of the Science Symposium 2007. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2007. November; 13(11): 1268–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giralt S, Garderet L, Durie B, Cook G, Gahrton G, Bruno B, et al. American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network, and International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Conference on Salvage Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015. December; 21(12): 2039–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonsalves WI, Buadi FK, Ailawadhi S, Bergsagel PL, Chanan Khan AA, Dingli D, et al. Utilization of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of multiple myeloma: a Mayo Stratification of Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) consensus statement. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018. July 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, Shaughnessy J, Gutierrez N, Stewart AK, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia 2009. December; 23(12): 2210–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, Lokhorst HM, Goldschmidt H, Rosinol L, et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2015. September 10; 33(26): 2863–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahebi F, Garderet L, Kanate AS, Eikema DJ, Knelange NS, Alvelo OFD, et al. Outcomes of Haploidentical Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma: An EBMT/CIBMTR Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019. February; 25(2): 335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castagna L, Mussetti A, Devillier R, Dominietto A, Marcatti M, Milone G, et al. Haploidentical Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma Using Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017. September; 23(9): 1549–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishihori T, Ochoa-Bayona JL, Kim J, Pidala J, Shain K, Baz R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for consolidation of VGPR or CR for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013. September; 48(9): 1179–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Corral L, Caballero-Velazquez T, Lopez-Godino O, Rosinol L, Perez-Vicente S, Fernandez-Aviles F, et al. Response to Novel Drugs before and after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019. September; 25(9): 1703–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soiffer RJ, Chen YB. Pharmacologic agents to prevent and treat relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv 2017. November 28; 1(25): 2473–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosh N, Ye X, Tsai HL, Bolanos-Meade J, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L, et al. Allogeneic Blood or Marrow Transplantation with Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide as Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis in Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017. November; 23(11): 1903–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith E, Devlin SM, Kosuri S, Orlando E, Landau H, Lesokhin AM, et al. CD34-Selected Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Patients with Relapsed, High-Risk Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016. February; 22(2): 258–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raje NS, Bardeja JG, Lin Y, Munshi N, Siegel DS, Liedtke M, et al. bb2121 anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Updated results from a multicenter phase I study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(Suppl): Abstr 8007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghosh A, Mailankody S, Giralt SA, Landgren CO, Smith EL, Brentjens RJ. CAR T cell therapy for multiple myeloma: where are we now and where are we headed? Leuk Lymphoma 2017. November 6: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park JH, Riviere I, Gonen M, Wang X, Senechal B, Curran KJ, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of CD19 CAR Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018. February 1; 378(5): 449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018. February 1; 378(5): 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017. December 28; 377(26): 2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak O, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2017. December 28; 377(26): 2545–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.