Abstract

The σ2 receptor is a potential in vivo target for measuring proliferative status in cancer. The feasibility of using N-(4-(6,7-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)butyl)-2-(2-18F-fluoroethoxy)-5-methylbenzamide (18F-ISO-1) to image solid tumors in lymphoma, breast cancer, and head and neck cancer has been previously established. Here, we report the results of the first dedicated clinical trial of 18F-ISO-1 in women with primary breast cancer. Our study objective was to determine whether 18F-ISO-1 PET could provide an in vivo measure of tumor proliferative status, and we hypothesized that uptake would correlate with a tissue-based assay of proliferation, namely Ki-67 expression. Methods: Twenty-eight women with 29 primary invasive breast cancers were prospectively enrolled in a clinical trial (NCT 02284919) between March 2015 and January 2017. Each received an injection of 278–527 MBq of 18F-ISO-1 and then underwent PET/CT imaging of the breasts 50–55 min later. In vivo uptake of 18F-ISO-1 was quantitated by SUVmax and distribution volume ratios and was compared with ex vivo immunohistochemistry for Ki-67. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests assessed uptake differences across Ki-67 thresholds, and Spearman correlation tested associations between uptake and Ki-67. Results: Tumor SUVmax (median, 2.0 g/mL; range, 1.3–3.3 g/mL), partial-volume–corrected SUVmax, and SUV ratios were tested against Ki-67. Tumors stratified into the high–Ki-67 (≥20%) group had SUVmax greater than the low–Ki-67 (<20%) group (P = 0.02). SUVmax exhibited a positive correlation with Ki-67 across all breast cancer subtypes (ρ = 0.46, P = 0.01, n = 29). Partial-volume–corrected SUVmax was positively correlated with Ki-67 for invasive ductal carcinoma (ρ = 0.51, P = 0.02, n = 21). Tumor–to–normal-tissue ratios and tumor distribution volume ratio did not correlate with Ki-67 (P > 0.05). Conclusion: 18F-ISO-1 uptake in breast cancer modestly correlates with an in vitro assay of proliferation.

Keywords: breast cancer; σ-2; TMEM-97, proliferation; 18F-ISO-1

Tumor proliferative status is a key measure of breast cancer aggressiveness. The pathologic gold standard for measuring breast cancer proliferation is Ki-67, a nuclear protein expressed in proliferating cells, especially in G2, M, and the latter half of S phase, but absent in quiescent cells in the G0 phase (1,2). High expression of Ki-67 in breast cancer is a prognostic marker associated with increased recurrence and decreased survival (3–6). Ki-67 is also predictive for breast cancer response to chemotherapy and other systemic therapies (7–9). In addition, Ki-67 can be an early indicator of response for estrogen receptor (ER)–targeted therapy of ER-positive cancers (10–12).

The σ2 receptor (σ2R) is a biomarker of proliferative status in cancer, validated in mammary adenocarcinoma cells in vitro (13) and solid tumors (14). A σ2R-selective radioligand, N-(4-(6,7-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)butyl)-2-(2-18F-fluoroethoxy)-5-methylbenzamide (18F-ISO-1), was developed to image σ2R expression (15). The ability of 18F-ISO-1 to measure σ2R binding as an indicator of cellular proliferation was validated in preclinical models and revealed a linear relationship between 18F-ISO-1 uptake and proliferative status of breast tumor xenografts (16). The gene coding for σ2R is transmembrane protein 97 (TMEM-97) (17). TMEM-97 is overexpressed in a variety of cancers and linked to poor prognosis (18,19). In a cellular model of breast cancer, expression of TMEM-97 parallels radioligand binding of 18F-ISO-1, and 18F-ISO-1 correlates with tumor proliferative status as assessed by Ki-67 and other markers (20). The active form of σ2R is in a ternary complex with progesterone receptor membrane component 1 and the low-density lipoprotein receptor, which together increase the rate of cellular internalization of low-density lipoproteins (21).

Dehdashti et al. (22) identified σ2R-targeting 18F-ISO-1 as a biomarker of proliferation in a mixed tumor population. The purpose of this study was to evaluate 18F-ISO-1 in a cohort of 28 breast cancer patients to further evaluate the feasibility of using this PET radiotracer as an in vivo breast cancer proliferation biomarker.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

Patients were recruited and gave written informed consent to participate in the study “18F-ISO-1 PET/CT in Breast Cancer” (NCT02284919) between March 2015 and January 2017. The study protocol is described at clinicaltrials.gov. Key inclusion criteria were a new diagnosis of breast cancer with a single diameter of at least 1 cm on conventional imaging and no prior treatment. Candidates were identified at the time of biopsy and consented after pathologic confirmation of disease. The study and informed consent were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and the Cancer Center Clinical Trials Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee. All imaged subjects were included in this analysis and were at least 18 y old, not pregnant, and willing to undergo a PET/CT scan.

18F-ISO-1 PET/CT Imaging

18F-ISO-1 was produced by the University of Pennsylvania Cyclotron Facility under U.S. Pharmacopeia–compliant procedures, as previously described (23) and administered under a Food and Drug Administration–approved exploratory investigational new drug application (124129). The mean and SD of the administered mass of 18F-ISO-1 were 2.8 ± 2.6 μg (range, 0.12–9.9 μg). The mean administered activity was 468.16 ± 54.18 MBq (range, 278–527 MBq). One-hour dynamic imaging of the breasts was followed by a whole-body static scan. There were no adverse or clinically detectable pharmacologic effects in any of the 28 subjects. No significant changes in vital signs were observed. All studies were on an Ingenuity TF PET/CT device (Philips Healthcare) using a previously described method of image reconstruction (24). Tumors’ static SUVmax and SUVpeak (25), as well as background uptake, were measured from a summed 50- to 55-min image. This time point was chosen to maximize uptake while compensating for inconsistent time-bin lengths for the final frame. Nonspecific binding of 18F-ISO-1 in background was estimated from the average radiotracer concentration in normal tissue, calculated from a 15-mm-diameter sphere placed on the contralateral breast or from a 20-mm-sphere placed on the left latissimus dorsi. A smaller normal-breast region was used to facilitate matching contralateral normal-breast placement to tumor location. SUVs were measured using PMOD image analysis software (version 3.7; PMOD Technologies Ltd.), with masking to reference-standard (Ki-67) data. Tumors were measured in 3 dimensions using MRI and CT for partial-volume correction (PVC). PVC of tumor radiotracer uptake was calculated as previously described (26) using normal-breast background uptake and recovery coefficient curves measured using phantom images of spheres acquired on this study’s PET/CT scanner. Imaging measures are reported as SUVmax, tumor–to–normal-breast ratios (SUVmax/NBr), and tumor–to–normal-muscle ratios (SUVmax/NM).

Kinetic Analyses

Distribution volume ratios (DVRs) were calculated for tumor 18F-ISO-1 peak uptake using PMOD via the Logan reference tissue model (27). Normal breast was used as the reference tissue. A population average k2′ of 0.05 ± 0.05 (1/min), n = 18, was calculated using the Ichise multilinear reference tissue model for each patient, then averaging to reduce noise, while excluding physiologically meaningless negative k2′ values (28).

Immunohistochemistry

The Ki-67 index (fraction of proliferating cells) was assessed using the diagnostic protocol validated for clinical Ki-67 measurements. Immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 was performed on fixed whole-slide tumor sections on an automated platform (Leica Bond-III instrument; Leica Biosystems) using a monoclonal mouse antibody (anti–human Ki-67 antigen, clone MIB-1, IR626; Dako). Briefly, 5-μm-thick unstained sections cut from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were obtained on charged slides. Sections were deparaffinized and hydrated, followed by heat-induced epitope retrieval, treatment with low-pH buffer, and treatment with primary antibody for 15 min. Slides were rinsed with wash buffer and analyzed using the Bond Polymer Refine Detection System as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclear staining for Ki-67 was scored using the Aperio image analysis platform (Leica Biosystems Imaging). Appropriate positive (tonsil) and negative reagent controls were evaluated. Automated immunohistochemistry image analysis counting more than 1,000 nuclei was used, following the guidelines of the International Ki-67 in Breast Cancer Working Group, and reported as the percentage of nuclei positive for Ki-67 (4).

Statistical Analyses

We hypothesized that 18F-ISO-1 PET uptake measures can quantitate in vivo breast cancer proliferative status, and we tested for correlations between Ki-67 score as a biomarker for proliferation and 18F-ISO-1 uptake. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 25. Spearman rank correlation was used to estimate the strength of association between tracer uptake and Ki-67. The threshold for high versus low Ki-67 was defined as 20%, based on a 2017 study of early-stage breast cancers (29) and the 2015 St. Gallen meeting consensus (30). In addition, a 14% Ki-67 threshold was also examined based on the earlier 2011 St. Gallen meeting consensus (31). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare tracer uptake between high-proliferation tumors (Ki-67 ≥ 14% or 20%) and low-proliferation tumors (Ki-67 < 14% or 20%). Analyses were repeated in invasive ductal and ER-positive tumors. Statistical significance was assessed on the basis of a 2-sided α of 0.05. The sample size was estimated to provide 80% power to detect a correlation of 0.47 using a 5% type I error rate (2-tailed).

RESULTS

Study Participant Characteristics

Twenty-nine women were enrolled in the study, and 1 patient declined imaging after enrollment. Twenty-eight women with 29 tumors underwent 18F-ISO-1 PET/CT scans before initiation of any cancer-directed therapy. The age range was 32–79 y (median, 55 y). The histology of the primary breast malignancy was invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) in 21 (72%), invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) in 4 (14%), and mixed IDC and ILC in 4 (14%). Study participant and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Most cases (n = 18) were early stage (1A and 2A). The mean tumor diameter (average of planar diameters) ranged from 7 to 81 mm.

TABLE 1.

Study Participant and Tumor Characteristics

| Characteristic | Data |

| Age range (y) | 32–79 (median, 55) |

| Female (n) | 28 (28/28 = 100%) |

| Race (n) | |

| Caucasian | 17 (17/28 = 61%) |

| Black | 9 (9/28 = 32%) |

| Asian | 1 (1/28 = 4%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1/28 = 4%) |

| Histology (n) | |

| IDC | 21 (21/29 = 72%) |

| ILC | 4 (4/29 = 14%) |

| Mixed (IDC and ILC) | 4 (4/29 = 14%) |

| Histologic grade (n) | |

| 1 | 2 (2/29 = 7%) |

| 2 | 15 (15/29 = 52%) |

| 3 | 11 (11/29 = 38%) |

| Not graded | 1 (1/29 = 3%) |

| AJCC tumor anatomic stage group* (n) | |

| 1A | 9 (9/29 = 31%) |

| 2A | 9 (9/29 = 31%) |

| 2B | 7 (7/29 = 25%) |

| 3A | 2 (2/29 = 7%) |

| 3B | 1 (1/29 = 4%) |

| IV | 1 (1/29 = 4%) |

| Receptor status (n) | |

| ER+ or PR+/HER2− | 20 (20/29 = 69%) |

| HER2+ | 5 (5/29 = 17%) |

| Triple-negative (ER−/PR−/HER2−) | 4 (4/29 = 14%) |

According to AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.

AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; PR = progesterone receptor; HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Measurements of 18F-ISO-1 Uptake and Association with Ki-67

Tumor SUVmax, SUVmax–to–normal-tissue ratios, DVR, mean tumor diameter, and the histology of the primary breast malignancies for the entire cohort are provided in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). Median SUVmax was 2.0 g/mL (range, 1.3–3.3 g/mL). Uptake in normal contralateral breast tissue ranged from 0.5 to 1.7 g/mL, with a median of 0.9 g/mL. Tumor SUVmax/NBr had a median value of 2.1 (range, 1.0–4.6), while the tumor SUVmax/NM median was 1.5 (range, 0.6–3.6). Physiologic 18F-ISO-1 uptake was seen in the liver, gallbladder, bowel, and pancreas and was similar to prior studies (1). 18F-ISO-1–avid lesions were observed in the breast, axillary nodes, and extraaxillary nodes, and a previously unknown metastasis to the lung was confirmed with 18F-FDG PET/CT.

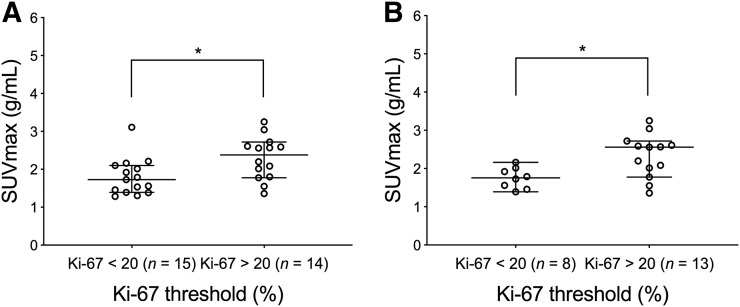

Representative images from tumors with a low and high Ki-67 proliferative status (Ki-67 < or ≥ 20%) (29,30) are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Plots of tumor SUVmax grouped by high and low Ki-67 (n = 29) are depicted in Figure 3A. Based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, there was a significant difference in SUVmax between tumors stratified by low (n = 15) and high (n = 14) Ki-67, with SUVmax in tumors with a low Ki-67 being significantly lower than that in tumors with a high Ki-67 (P = 0.02) (Table 2). Since ductal cancers generally grow in a discrete spheric or round pattern, unlike the lobular subset, which presents with more infiltrative linear strands of tumor cells loosely dispersed in the fibrous stroma of breast, we also assessed the association between 18F-ISO-1 and cellular proliferation for the IDC subset (Fig. 3B). The SUVmax of IDC tumors with a low Ki-67 (n = 8) was significantly lower than that of tumors with a high Ki-67 (n = 13; P = 0.02) (Table 2).

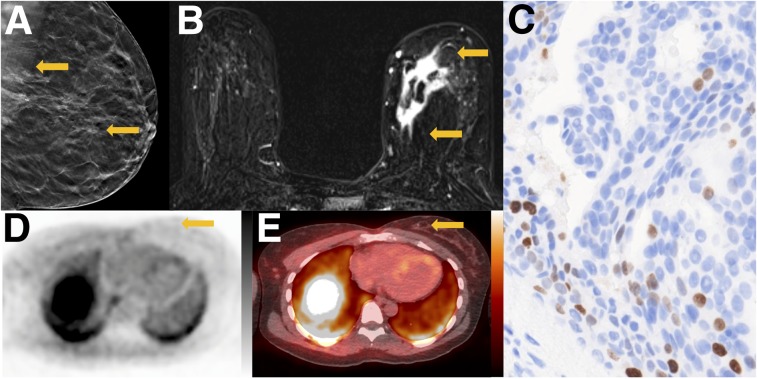

FIGURE 1.

Tumor with low proliferative status. A 42-y-old woman with ER-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative primary breast cancer. (A) Tomosynthesis mediolateral oblique projection demonstrates irregular mass with spiculated margins and associated calcifications (arrows). (B) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted subtraction image demonstrates irregular mass in medial breast with heterogeneous enhancement (arrows). (C) Ki-67 staining demonstrates low percentage of actively dividing cells (11%) (×20). (D) Axial 18F-ISO-1 image demonstrates no qualitative uptake in medial breast (arrow, SUVmax of 1.5 g/mL). (E) Corresponding 18F-ISO-1 PET/CT demonstrates biopsy clip marking site of malignancy (arrow). PET and PET/CT images are scaled to 0–5 g/mL SUV, −160 to +240 HU.

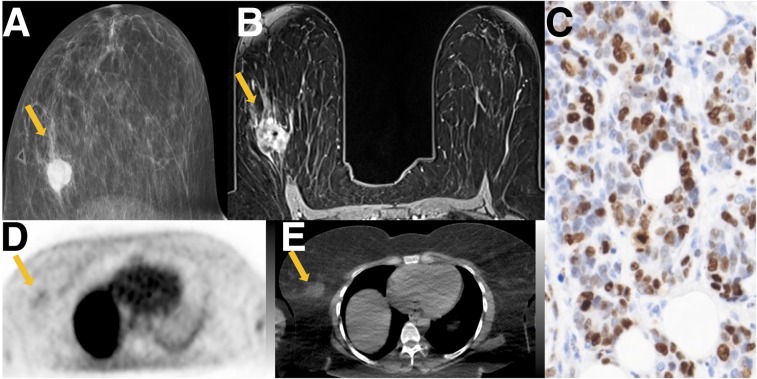

FIGURE 2.

Tumor with high proliferative status. A 40-y-old woman with triple-negative breast cancer. (A) Mammographic craniocaudal projection demonstrates high-density irregular mass (arrow) with overlying palpable marker. (B) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image demonstrates that mass (arrow) is irregular with heterogeneous enhancement, with central signal dropout from biopsy marker. (C) Ki-67 staining demonstrates high percentage of actively dividing cells (74%) (×20). (D) Axial 18F-ISO-1 image demonstrates qualitative uptake at site of malignancy (arrow; SUVmax of 2.6 g/mL) (E) Corresponding CT image demonstrates irregular mass (arrow). PET and CT images are scaled to 0–5 g/mL SUV, −160 to +240 HU.

FIGURE 3.

Plot of SUVmax in groups stratified by Ki-67 below or above 20. (A) SUVmax shows significant difference between patient tumors stratified by low (n = 15) and high (n = 14) Ki-67 values in all 29 tumors. (B) SUVmax stratified by low (n = 8) and high (n = 13) Ki-67 values restricted to IDC (n = 21) show significant differences based on Ki-67 threshold. Center line of each distribution indicates median value; error bars show 95% confidence interval of median. *P < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test of Tumor 18F-ISO-1 Uptake Grouped by Ki-67 20% Threshold

|

P |

|||

| Ki-67 vs…. | All tumors (n = 29) | ER+(n = 20) | IDC (n = 21) |

| SUVmax | 0.02* | 0.03* | 0.02* |

| SUVmax/NBr | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.12 |

| SUVmax/NM | 0.95 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

| DVR | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| PVC SUVmax | 0.16 | 0.57 | <0.01* |

P < 0.05.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was repeated with a lower, 14%, Ki-67 threshold from the earlier 2011 St. Gallen meeting consensus (31) to stratify tumor proliferation as low (n = 10) or high (n = 19). The lower-threshold analysis found that 18F-ISO-1 SUVmax, SUVmax/NBr, and DVR were significantly lower in tumors with a low Ki-67 than in tumors with a high Ki-67 (P ≤ 0.02).

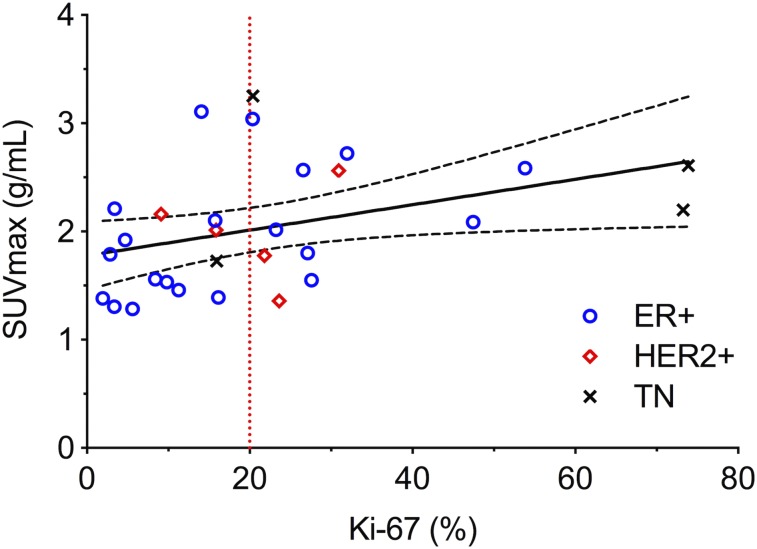

Spearman rank analysis found that 18F-ISO-1 uptake via SUVmax exhibited a significant positive association with Ki-67 proliferation scores across all breast cancers (ρ = 0.46, P = 0.01 in Fig. 4 and Table 3). Subsets of ER-positive tumors and IDC tumors also showed significant correlations between SUVmax and Ki-67 (ρ = 0.51, P = 0.02, and ρ = 0.44, P = 0.04, respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Scatterplots of SUVmax vs. Ki-67 for all 29 tumors. Spearman tests found significant correlations with Ki-67 (ρ = 0.46, P = 0.01). Solid linear regression trend line and dashed 95% confidence intervals are included for reference. TN = triple-negative.

TABLE 3.

Spearman Rank Correlations Between 18F-ISO-1 Uptake and Ki-67

| All tumors (n = 29) |

ER+ (n = 20) |

IDC (n = 21) |

||||

| Ki-67 vs…. | ρ | P | ρ | P | ρ | P |

| SUVmax | 0.46 | 0.01* | 0.51 | 0.02* | 0.44 | 0.04* |

| SUVmax/NBr | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| SUVmax/NM | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.79 | −0.09 | 0.68 |

| DVR | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| PVC SUVmax | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.01* |

P < 0.05.

Additional measurements of tumor-to-background ratio, PVC SUV (to determine whether correlations were dependent on lesion size), and tumor DVR were examined for associations with Ki-67. PVC SUVmax was not associated with Ki-67 for all breast cancers (P > 0.05, n = 29), but was for invasive ductal cancers (Wilcoxon: P = 0.001; Spearman: ρ = 0.53, P = 0.01, n = 21, in Tables 2 and 3). The 18F-ISO-1 SUVmax/NBr and SUVmax/NM were not significant for any cancers or for individual subtypes, but the correlation between SUVmax/NBr and Ki-67 had a trend toward significance (P = 0.08). Tumor DVR was not correlated with Ki-67 (P ≥ 0.1).

DISCUSSION

This prospective clinical trial of in vivo 18F-ISO-1 uptake in 28 breast cancer patients is, to our knowledge, the first focused trial of this tracer in breast cancer and demonstrated that SUVmax correlates with in the vitro Ki-67 index of proliferation whereas tumor–to–normal-breast ratio and DVR did not correlate with Ki-67 index, which supports the results of Dehdashti et al. (22). The in vivo association in breast cancer is also consistent with prior in vitro cell culture studies, as well as mouse studies using a highly selective, optically labeled (fluorescent) σ2R ligand probe, SW120, wherein SW120 binding was positively correlated with Ki-67 (32).

Although Ki-67 is a helpful biomarker, it requires tissue sampling, and measurement can be confounded by intratumoral heterogeneity, poor reproducibility, and subjective readings (5). An imaging method for measuring tumor proliferation offers a noninvasive approach to assaying proliferation in breast and other cancers that takes into account the whole tumor and allows for repeated noninvasive measurements. This has been previously shown in breast cancer. For example, a multicenter trial tested the PET radiotracer 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT) and measured uptake in primary breast cancer (n = 51 patients) in serial imaging over the course of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (33). 18F-FLT uptake correlated with posttherapy Ki-67 scores (P ≤ 0.04) on surgical specimens, and serial uptake measures early in the course of treatment predicted response to therapy. However, 18F-FLT is trapped exclusively during S phase and not during G1, M, or G2, unlike Ki-67 and 18F-ISO-1, and may not fully represent tumor proliferative status (34). An imaging method more similar to Ki-67 labeling, such as 18F-ISO-1 PET, could assay all components of tumor proliferative status, taking into account cells in all phases of the cell cycle. This might be especially helpful in evaluating response to cytostatic therapies, such as cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK 4/6) inhibitors. A recent preclinical study testing 18F-FLT and 18F-ISO-1 for monitoring breast cancer response to a combination of CDK 4/6 inhibition and endocrine therapy concluded that 18F-FLT was more sensitive to early changes in S phase arising from combined treatment, whereas 18F-ISO-1 was better suited to quantitating delayed changes and to assessing the impact of CDK 4/6 inhibition on G1 phase to G0 phase arrest and overall tumor impact (35), supporting a potential clinical role for a tracer of tumor proliferative status, such as 18F-ISO-1. 18F-ISO-1 may also be useful as a companion diagnostic for σ2-targeted therapeutic applications, currently under study (34–36).

Our study of a single primary tumor type in a larger breast cancer cohort did not find a significant correlation between 18F-ISO-1 tumor–to–normal muscle ratios and Ki-67 (P = 0.72), unlike the report of Dehdasthi et al. showing a correlation between tumor–to–normal muscle ratio and Ki-67 index (P = 0.003) (2). This difference may be related to variability in normal muscle uptake, which may be more impactful for a less proliferative malignancy, such as breast cancer, with decreased tumor uptake of radiotracer when compared with the more proliferative malignancies such as lymphoma and head and neck included in the Dehdashti study.

Our study has some limitations: breast cancer, as compared with many other solid tumor types, is a tumor with relatively low proliferation, and thus the range of SUVs is limited, especially for this largely ER-positive tumor population, limiting our ability to assess correlation over the full spectrum of tumor proliferative status. Measures of PVC PET (PVC SUVmax) correlated with Ki-67 scores only in patients with IDC (P < 0.01, n = 21). A potential explanation is that the PVC correction model (26) was based on all the tumors having an ideal spheric shape, which is more applicable in IDC than in ILC, because ILC tumors grow as ill-defined asymmetric lesions infiltrating the normal breast parenchyma in a linear single-file pattern. As such, partial-volume corrections might be expected to be less accurate for ILC than for IDC. Additionally, because the gene coding for σ2R was not known when the study was designed and conducted, a pathologic assay for TMEM-97 was not prospectively planned in the institutional review board–approved study protocol. This limitation will be addressed in future studies. The uptake of 18F-ISO-1 in breast cancer is relatively low, and there is relatively high background activity seen on PET images in the fatty tissue of the breast, limiting its clinical value, particularly for low-proliferation tumors. We also note that 18F-ISO-1 has a more modest uptake and target-to-background ratio than other tracers tested for application to breast cancer, such as 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT, limiting its applicability. However, it is intended as a quantitative biomarker of proliferation, supported by our results, and not as a tool for detection and staging. 18F-ISO-1 instead may provide a basis for σ2R-based imaging of proliferation, including potential for assessing response to cell-cycle–targeted therapy. Further study of more potent σ2R radiotracers in breast cancer patients is warranted, with a goal of increasing the uptake of radiotracer in tumors relative to background tissue.

CONCLUSION

Uptake of the σ2 ligand, 18F-ISO-1, correlates with an established tissue assay marker of tumor proliferative status, Ki-67. This finding supports the 18F-ISO-1 uptake findings of Dehdashti et al. and can be used to design studies assessing 18F-ISO-1 or more potent σ2-targeting radiotracers in vivo for potential use in complementing other means of guiding cell-cycle–targeted agents.

DISCLOSURE

Elizabeth McDonald was supported by Susan G. Komen Foundation (CCR 16376362, SAC130060) and the American Roentgen Ray Society Scholar award. Robert Doot was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (K01DA040023). This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000003); by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-SE0012476); by the Penn Radiology Department; and by the NCI Cancer Center (P30 CA016520). No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Can the novel radiotracer 18F-ISO-1 provide a whole-tumor measurement of breast cancer proliferative status?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: This exploratory study of 18F-ISO-1 demonstrated that this tracer provides a measure of tumor proliferative status (cycling cells) that correlates with a tissue-based pathologic assay.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: 18F-ISO-1 PET/CT may be complementary to other methods for imaging cellular proliferation. 18F-ISO-1 or more potent σ2-targeting radiotracers could be investigated further for possible use to help guide the use of cell-cycle–targeted agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank those who contributed substantially to the work reported in the article: Karen J. Palmer, Regan Sheffer, Federico Valdivieso, Noah Goodman, and Tiffany Dominguez.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker HH, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984;133:1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowsett M, Nielsen TO, A’Hern R, et al. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1656–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodson WH. III, Moore DH. II, Ljung BM, et al. The prognostic value of proliferation indices: a study with in vivo bromodeoxyuridine and Ki-67. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trihia H, Murray S, Price K, et al. Ki-67 expression in breast carcinoma: its association with grading systems, clinical parameters, and other prognostic factors—a surrogate marker? Cancer. 2003;97:1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Diest PJ, van der Wall E, Baak JP. Prognostic value of proliferation in invasive breast cancer: a review. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petit T, Wilt M, Velten M, et al. Comparative value of tumour grade, hormonal receptors, Ki-67, HER-2 and topoisomerase II alpha status as predictive markers in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang J, Ormerod M, Powles TJ, Allred DC, Ashley SE, Dowsett M. Apoptosis and proliferation as predictors of chemotherapy response in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:2145–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faneyte IF, Schrama JG, Peterse JL, Remijnse PL, Rodenhuis S, van de Vijver MJ. Breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: predictive markers and relation with outcome. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis MJ, Suman VJ, Hoog J, et al. Ki67 proliferation index as a tool for chemotherapy decisions during and after neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment of breast cancer: results from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031 Trial (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goncalves R, DeSchryver K, Ma C, et al. Development of a Ki-67-based clinical trial assay for neoadjuvant endocrine therapy response monitoring in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165:355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowsett M, Smith IE, Ebbs SR, et al. Proliferation and apoptosis as markers of benefit in neoadjuvant endocrine therapy of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1024s–1030s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mach RH, Smith CR, al-Nabulsi I, Whirrett BR, Childers SR, Wheeler KT. Sigma 2 receptors as potential biomarkers of proliferation in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler KT, Wang LM, Wallen CA, et al. Sigma-2 receptors as a biomarker of proliferation in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1223–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sai KK, Jones LA, Mach RH. Development of 18F-labeled PET probes for imaging cell proliferation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:892–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoghi KI, Xu J, Su Y, et al. Quantitative receptor-based imaging of tumor proliferation with the sigma-2 ligand [18F]ISO-1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alon A, Schmidt HR, Wood MD, Sahn JJ, Martin SF, Kruse AC. Identification of the gene that codes for the sigma2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:7160–7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding H, Gui XH, Lin XB, et al. Prognostic value of MAC30 expression in human pure squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2705–2710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han KY, Gu X, Wang HR, Liu D, Lv FZ, Li JN. Overexpression of MAC30 is associated with poor clinical outcome in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elmi A, Makvandi M, Weng CC, et al. Cell-proliferation imaging for monitoring response to CDK4/6 inhibition combined with endocrine-therapy in breast cancer: comparison of [18F]FLT and [18F]ISO-1 PET/CT. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3063–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riad A, Zeng C, Weng CC, et al. Sigma-2 receptor/TMEM97 and PGRMC-1 increase the rate of internalization of LDL by LDL receptor through the formation of a ternary complex. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dehdashti F, Laforest R, Gao F, et al. Assessment of cellular proliferation in tumors by PET using 18F-ISO-1. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu Z, Xu J, Jones LA, et al. Radiosynthesis and biological evaluation of a promising σ2-receptor ligand radiolabeled with fluorine-18 or iodine-125 as a PET/SPECT probe for imaging breast cancer. Appl Radiat Isot. 2010;68:2268–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolthammer JA, Su KH, Grover A, Narayanan M, Jordan DW, Muzic RF. Performance evaluation of the Ingenuity TF PET/CT scanner with a focus on high count-rate conditions. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59:3843–3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(suppl):122S–150S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson LM, Mankoff DA, Lawton T, et al. Quantitative imaging of estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer with PET and 18F-fluoroestradiol. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, et al. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deluche E, Venat-Bouvet L, Leobon S, et al. Assessment of Ki67 and uPA/PAI-1 expression in intermediate-risk early stage breast cancers. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coates AS, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A, et al. Tailoring therapies: improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2015. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1533–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, et al. Strategies for subtypes: dealing with the diversity of breast cancer—highlights of the St. Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1736–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng C, Vangveravong S, Jones LA, et al. Characterization and evaluation of two novel fluorescent sigma-2 receptor ligands as proliferation probes. Mol Imaging. 2011;10:420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostakoglu L, Duan F, Idowu MO, et al. A phase II study of 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine PET in the assessment of early response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results from ACRIN 6688. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1681–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmi A. McDonald ES, Mankoff D. Imaging tumor proliferation in breast cancer: current update on predictive imaging biomarkers. PET Clin. 2018;13:445–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald ES, Mankoff DA, Mach RH. Novel strategies for breast cancer imaging: new imaging agents to guide treatment. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(suppl 1):69S–74S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald ES, Mankoff J, Makvandi M, et al. Sigma-2 ligands and PARP inhibitors synergistically trigger cell death in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.