Dear Editor,

In their systematic review on the clinical characteristics of COVID-19, Wu and colleagues report a 3.2% case fatality rate (CFR), ranging from 2% to 4% [1] with strong heterogeneity between studies (I2 =100%). One study from the initial phase of the epidemic in Wuhan showed higher CFR and was responsible of the heterogeneity of results [2]. The authors suggest that higher complication and fatality rate in Wuhan could be due to the limited clinical experience in the initial phase of the epidemic.

When comparing data from China to those from Italy, CFR is the most impressive difference, with data from Italy, and now also from other European countries [3], reporting rates three to ten times higher than in China [1,4].

Other studies tried to justify this difference as due to the extremely old Italian population and provided similar age-specific CFR in the two countries [5]. But this was in an initial phase of the epidemic, when official statistics reported 7.2% CFR in Italy. Now overall CFR reported by routine statistics in Italy, Spain, UK, The Netherlands and France is over 10% [1] and it is difficult to justify the difference only with the older age of patients. Here we propose a simple explanation: the length of follow up.

We report data from the COVID-19 information system set up in Italy by the National Institute of Health and described elsewhere [5,6], diagnosed from February 20 to March 29 and followed up to April 5 in Emilia-Romagna region (approximately 4.5 million inhabitants). Briefly the dataset collects individual information on date of symptom onset, RT-PCR test, hospitalization, intensive care admission, death or recovery for all SAR-2-CoV RT-PCR positive patients in Italy.

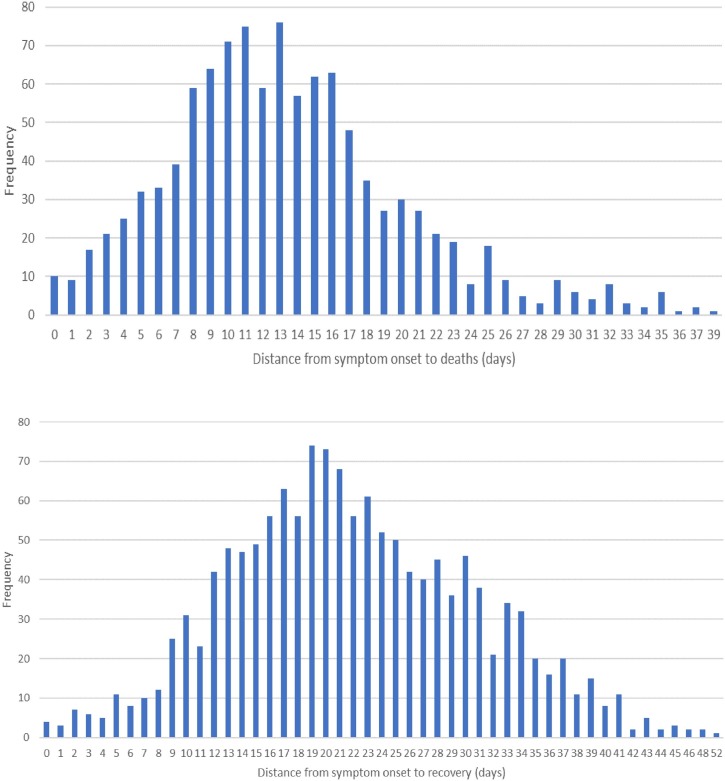

The CFR increases with the length of follow up of cases, from 8% for cases diagnosed between March 23 and March 29, to about 20% for those diagnosed from February 20 to March 8 (Table 1 ). Including only cases with symptom onset (or laboratory diagnosis, when symptom onset was not reported) before March 15, ie with at least 22 days of follow up, we constructed a frequency distribution of the distance from symptom onset to death (Fig. 1 a). The median in this subpopulation is 12 days.

Table 1.

cases, deaths and case fatality rate, by calendar period and, for patients with at least 22 days of follow up, by age and sex. Emilia-Romagna region, 2020.

| All cases | cases | deaths | Case fatality rate | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| calendar period | ||||

| February 10 to March 1 | 1361 | 277 | 20.4 | (18.2–22.6) |

| March 2 to March 8 | 2133 | 423 | 19.8 | (18.2–21.6) |

| March 9 to March 15 | 4070 | 595 | 14.6 | (13.5–15.7) |

| March 16 to March 22 | 4561 | 492 | 10.8 | (9.9–11.7) |

| March 23 to March 29 | 2897 | 208 | 7.2 | (6.3–8.2) |

| Restricted to period from 10/02/2020 to 8/03/2020a | ||||

| Age | ||||

| <50 | 771 | 7 | 0.9 | (0.3–2.6) |

| 50-59 | 625 | 27 | 4.3 | (3.1–6.9) |

| 60-69 | 660 | 83 | 12.6 | (10.4–16.0) |

| 70-79 | 775 | 257 | 33.2 | (30.7–37.9) |

| >=80 | 662 | 326 | 49.2 | (45.0–53.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| males | 2129 | 507 | 23.8 | (22.0–25.7) |

| females | 1290 | 182 | 14.1 | (12.3–16.1) |

One case with missing age and 75 missing sex.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of deaths (upper) and recoveries (clinical or virological) (lower) by time since symptom onset or diagnosis (if symptoms are not reported) of COVID-19. Here are included only cases with at least 22 days of follow up, ie with disease onset before March 15. 1064 deaths (52% of the total deaths as of April 5) and 1392 recoveries (63.2% of the total recoveries as of April 5).

The definition of clinically recovered patients includes patients with two consecutive negative swabs and those who had no symptoms in the preceding three days at least. The median time to recovery is 20 days. Given that the minimum follow up in this cohort is 22 days, we are by far underestimating the median time to recovery.

Our data show that, according to the Italian definition of COVID-related death [5,6], the CFR can reach about 20% if we follow up patients for a long enough time to observe the vast majority of deaths. These findings are identical to those in other Italian regions [6]. It is possible that Italian surveillance is now testing only severe cases, thus overestimating CFR, but the increase with increasing observation time is probably generalizable to other case definitions. Unfortunately, previous studies did not focus on this point.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The following are members of the Emilia-Romagna COVID-19 working group: Andrea Mattivi, Giulio Matteo, Serena Broccoli, Erika Massimiliani, Gabriella Frasca, Massimo Clo, Claudio Voci, Luisa Loli Piccolomini, Rossana Mignani, Paola Angelini, Giovanna Mattei, Adriana Giannini.

Footnotes

Correspondence to: Hu Y, Sun J, Dai Z, et al. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 14]. J Clin Virol. 2020; 127: 104371. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371.

References

- 1.Hu Y., Sun J., Dai Z. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127:104371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(February (10223)):497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. Published: February 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu L., Wang B., Yuan T. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;(March (23)) doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riccardo F., Ajelli M., Andrianou X.D. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases in Italy and estimates of the reproductive numbers one month into the epidemic. medRxiv Preprint. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.08.20056861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]