Abstract

In plants, the calmodulin (CaM) proteins is an important calcium-binding protein, which play a crucial role in both regulating plant growth and development, as well as in the resistance mechanisms to various biotic and abiotic stresses. However, there is limited knowledge available on the CaM family functions in Solanum pennellii, a wild tomato species utilized as a genetic resource for cultivated tomatoes. In this study, 6 CaM (SpCaM) and 45 CaM-like (SpCML) genes from Solanum pennellii were selected for bioinformatics analysis to obtain insights into their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, conserved motifs, chromosomal locations, and promoters. The results showed that the 6 SpCaM proteins contained 4 EF-hand domains each, and the 45 SpCML proteins had 2-4 EF-hand domains. The 51 CaM and CaM-like genes contained different intron/exon patterns and they were unevenly distributed across the 12 chromosomes of S. pennellii. The results of the analysis of the conserved motifs and promoter cis-regulatory elements also indicated that these proteins were involved in the responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that the SpCaM and SpCML genes had broad expression patterns in abiotic stress conditions and with hormone treatments, in different tissues. The findings of this study will be important for further investigations of the calcium signal transduction mechanisms under stress conditions and lay a theoretical foundation for further exploration of the molecular mechanisms of plant resistance.

Subject terms: Plant physiology, Plant stress responses

Introduction

Plants are invariably subjected to stressful environmental conditions and pathogenic attacks from various bacteria, fungi, and viruses throughout their lives. To survive these biotic and abiotic stresses, plants have evolved adaptive molecular mechanisms, many of which involve calcium as a second messenger in cellular stress signal transductions1–4. When threatened, the rapid increase of Ca2+ concentrations in the cytoplasm causes calcium transients and calcium oscillations, which are the initial responses to the stimulus5, and lead to calcium being bound to sensor responders or sensor relays2. The sensor responders can combine calcium to generate signals directly and have functions as both sensors and effectors, which mainly include calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) proteins6. Sensor relays bound by Ca2+, however, need to interact with the target proteins to produce their signals, and they are mainly protein phosphatases, such as calmodulin (CaM), CaM-like (CML), and calcineurin B-like (CBL) proteins7.

CaM, is an essential calcium-binding protein, that has been identified in plants, several protozoa, and animals8. In plants, the typical CaM structure contains approximately 150 amino acid residues, and the structures of the different CaM proteins are highly conserved. CaM carries 4 EF-hand type calcium-binding domains that are 12 amino acid residues long each. Each of the 4 EF-hand domains binds to a Ca2+, and this binding changes the conformation of the CaM, thereby activating it to perform signal transductions. Another class of proteins, called CML, are structurally similar to the CaM and contain 1 to 4 EF-hand domains. Unlike the CaM proteins, some of CML EF-hand domains are not Ca2+ binding regions9–11. The CaM and CML family proteins have been identified in numerous plants. By means of genome-wide analysis, 6 CaM and 50 CML have been identified in Arabidopsis12. Furthermore, the genome of Oryza sativa was found to encode 5 CaM and 32 CML13, Solanum lycopersicum was found to 24 CML14, and soybean had 6 CaM and 144 CML15. They have also been identified in other cash crops, such as Vitis vinifera (3 CaM and 62 CML)4, Gossypium raimondii (6 CaM and 30 CML)11, Brassica rapa L. (79 CML)16, and Nicotiana benthamiana (7 CaM and 55 CML)8. However, currently, there is little biological information available on the CaM and CML families in Solanum pennellii.

The CaM and CML genes are widely distributed in plant cells, and there are different levels present in the tissues, and protoplasts12,14,16,17. Increasing evidence shows that CaM and CML genes play a vital role in plant growth and development, cell metabolism, and disease resistance18–22. During pollen germination and tube elongation in Arabidopsis, K + influx dependent on Ca2+ is regulated by AtCML2523; AtCML39 is significantly expressed in the process of light signal transduction to promoting seedling growth24. In trichome, kinesin-interacting Ca2+-binding protein (KIC) is a novel Ca2+ binding protein with an EF-hand motif, and modulates microtubule motor protein in response to changes in cytosolic Ca2+ and negatively regulates trichome stalk length and branching25. AtCML42 interacts with KIC to transmit the calcium signal downstream, which regulates the cell branch of the trichome26. The FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) is a negative regulator of plant flowering27. AtCML23 and AtCML24 proteins reduce the level of NO by transmitting calcium signals, which result in inhibition of the FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) gene expression, thus affecting the autonomic regulatory pathway of the transition to flowering28.

In addition, the functional roles in the various adversity stress are also revealed. Overexpression of MtCML40 causes the down-regulation of MtHKT1 (Na+ transport proteins 1) and led to greater accumulation of Na+ in shoots; thus rendering the transgenic M. truncatula seedlings more sensitive to salt stress29. In eukaryotes, MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) phosphatase (MKPs) are negative regulators of MAPKs. The wheat MKP (TMKP) contains a CaM binding domain and binds to CaM in a Ca(2+)-dependent manner30. The CaM/Ca2+ complex inhibits the catalytic activity of TMKP, but this activity was enhanced by the complex formations between CaM/Ca2+ and Mn2+. The dual regulation was mediated via the interactions between CaM/Ca2+ and the TMKP1 C-terminal CaM binding domain30. In tomatoes, CML43 was involved in the immune response to pathogens31. The overexpression of Arabidopsis CML8, improved resistance to pathogenic bacteria32.

The stress-tolerant wild tomato species Solanum pennelllii is a major genetic resource for the improvement of cultivated tomatoes33. For example, resistance genes have been discovered in Solanum pennelllii for powdery mildew34, and whitefly Bemisia argentifolii35, as well as genes associated with drought36 and salt tolerance37. In this study, we have selected 6 CaM and 45 CML genes from the Solanum pennellii genome and have performed bioinformatics analysis that included phylogenetic analysis, chromosomal localization, protein physicochemical parameter predictions, exon-intron structure analysis, and conserved motifs and cis-acting elements of the promoter region analysis, which provided basic information for the discovery of stress-response related genes in wild tomatoes and candidate genes for developing tomato stress-tolerant cultivars.

Results

Biochemical characteristics of the SpCaM and SpCML proteins

In previous studies, the amino acid sequences of the CaM and CML proteins in Arabidopsis and rice have been reported. In this study, 51 non-redundant sequences were identified in the Solanum pennellii genome, including 6 SpCaM and 45 SpCML33. All of the SpCaM and SpCML proteins were named according to their amino acid identity percentage with true canonical CaM7 (AtCaM7)12,13. Then, the biochemical characteristics of these proteins were predicted using the ExPASy proteomics server38 and Wolf PSORT program39 (Table 1). These SpCaM proteins shared more than 90% sequence similarity with AtCaM7. The number of amino acids (aa), molecular weight, isoelectric point (pi), and percentage of methionine in all the SpCaM proteins, except for SpCaM3, was 149, 16.8 kDa, 4.1, and 6.0%, respectively. The number of amino acids in the SpCML proteins varied from 129 to 282, except for SpCML43, which contained 340 amino acids. The molecular weights of the SpCML proteins ranged from 14.7 to 36.1 kDa, and their pi and percentage methionine ranged from 3.9 to 9.5 and 0.9 to 8.6%, respectively. Except for the absence of cysteine in SpCML5, SpCML9, SpCML12, and SpCML19, the rest of the SpCaM and SpCML proteins contained both cysteine and lysine. All SpCML and SpCaM proteins lacked the N-myristoylation sites, except for SpCML5, SpCML8, and SpCML36. SpCaM1-SpCaM6 possessed a standard structure characterized by 4 EF-hand type calcium-binding regions. The number of SpCML EF-hand domains varied from 1 to 4. The predicted results for the protein subcellular localizations of SpCaM and SpCML are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and names of the SpCaM and SpCML proteins identified in the Solanum pennellii genome.

| Gene name | Gene ID | aa | % of amino acids identity to ATCaM7 | EF-Hand No. | calcium-bindingregion No. | Mol Wt(kDa) | pi | Percentage methionine | Presence of cysteine | Presence of lysine | Potential myristoylation site | Sub-cell localizationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCaM1 | 107002231 | 149 | 100.00 | 4 | 4 | 16.85 | 4.11 | 6.00% | + | + | nucl: 5, mito: 3, extr: 3, cyto: 2, chlo: 1 | |

| SpCaM2 | 107001961 | 149 | 99.33 | 4 | 4 | 16.83 | 4.10 | 6.00% | + | + | nucl: 5, mito: 3, extr: 3, cyto: 2, chlo: 1 | |

| SpCaM3 | 107004451 | 180 | 99.33 | 4 | 4 | 20.51 | 4.61 | 6.70% | + | + | nucl: 5.5, cyto_nucl: 4.5, chlo: 4, cyto: 2.5, extr: 2 | |

| SpCaM4 | 107007179 | 149 | 99.33 | 4 | 4 | 16.83 | 4.10 | 6.00% | + | + | nucl: 5, mito: 3, extr: 3, cyto: 2, chlo: 1 | |

| SpCaM5 | 107008025 | 149 | 98.66 | 4 | 4 | 16.85 | 4.11 | 6.00% | + | + | nucl: 5, mito: 3, extr: 3, cyto: 2, chlo: 1 | |

| SpCaM6 | 107015299 | 149 | 91.95 | 4 | 4 | 16.93 | 4.15 | 6.00% | + | + | nucl: 7, cyto: 2, plas: 2, mito: 1, extr: 1, cysk: 1 | |

| SpCML1 | 107022582 | 149 | 78.23 | 4 | 4 | 16.95 | 3.96 | 6.00% | + | + | chlo: 4, cyto: 4, extr: 4, nucl: 1, cysk: 1 | |

| SpCML2 | 107013078 | 150 | 66.67 | 3 | 2 | 17.44 | 4.34 | 5.30% | + | + | cyto: 8.5, cyto_nucl: 7, nucl: 2.5, mito: 1, extr: 1, cysk_plas: 1 | |

| SpCML3 | 107029662 | 147 | 65.31 | 4 | 3 | 16.95 | 4.08 | 4.80% | + | + | cyto_nucl: 6, cyto: 5, chlo: 3, nucl: 3, extr: 3 | |

| SpCML4 | 107016234 | 191 | 50.73 | 4 | 4 | 21.09 | 4.40 | 4.70% | + | + | nucl: 11, chlo: 2, cyto: 1 | |

| SpCML5 | 107015376 | 147 | 50.34 | 3 | 1 | 16.53 | 4.90 | 3.40% | + | + | cyto: 7, plas: 3, chlo: 1, nucl: 1, extr: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML6 | 107028473 | 172 | 50.00 | 4 | 4 | 19.15 | 4.33 | 5.80% | + | + | nucl: 5, cyto: 4, extr: 2, chlo: 1, mito: 1, golg_plas: 1 | |

| SpCML7 | 107014545 | 163 | 48.65 | 4 | 4 | 18.01 | 4.35 | 3.10% | + | + | nucl: 5.5, nucl_plas: 5.5, plas: 4.5, cyto: 2, chlo: 1, mito: 1 | |

| SpCML8 | 107004453 | 147 | 46.98 | 3 | 1 | 16.56 | 4.89 | 4.10% | + | + | + | plas: 4, nucl: 3, cyto: 3, chlo: 1, extr: 1, pero: 1, golg: 1 |

| SpCML9 | 107026854 | 163 | 45.89 | 4 | 4 | 18.03 | 4.48 | 2.50% | + | nucl_plas: 6.5, nucl: 6, plas: 5, chlo: 2, mito: 1 | ||

| SpCML10 | 107011246 | 156 | 45.46 | 4 | 4 | 17.08 | 4.93 | 4.50% | + | + | chlo: 10, nucl: 4 | |

| SpCML11 | 107010502 | 198 | 43.08 | 2 | 2 | 22.76 | 4.63 | 3.00% | + | + | cyto: 3, E.R.: 3, mito: 2, vacu: 2, chlo: 1, plas: 1, extr: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML12 | 107027412 | 161 | 41.10 | 4 | 4 | 17.68 | 4.24 | 6.20% | + | cyto: 8.5, cyto_nucl: 8, nucl: 4.5, chlo: 1 | ||

| SpCML13 | 107013815 | 202 | 40.91 | 2 | 2 | 23.26 | 4.23 | 4.00% | + | + | vacu: 10, plas: 2, extr: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML14 | 107018599 | 150 | 40.88 | 4 | 4 | 17.00 | 4.33 | 6.70% | + | + | cyto: 8, chlo: 2, nucl: 2, mito: 1, cysk: 1 | |

| SpCML15 | 107021713 | 282 | 40.88 | 4 | 4 | 32.09 | 5.34 | 4.30% | + | + | chlo: 11, mito: 2, nucl: 1 | |

| SpCML16 | 107004268 | 151 | 40.58 | 4 | 3 | 17.29 | 4.10 | 7.90% | + | + | cyto: 4, nucl: 3, mito: 3, chlo: 2, extr: 2 | |

| SpCML17 | 107009322 | 145 | 40.58 | 4 | 4 | 16.19 | 4.92 | 5.50% | + | + | nucl: 7, cyto: 5, extr: 2 | |

| SpCML18 | 107030245 | 191 | 39.86 | 4 | 3 | 21.98 | 4.45 | 6.30% | + | + | cyto: 4.5, chlo: 4, cyto_nucl: 3, extr: 2, mito: 1, plas: 1, pero: 1 | |

| SpCML19 | 107014001 | 213 | 39.60 | 4 | 4 | 23.88 | 5.14 | 4.20% | + | chlo: 5, vacu: 2, E.R.: 2, nucl: 1, cyto: 1, mito: 1, pero: 1, golg: 1 | ||

| SpCML20 | 107028975 | 192 | 39.58 | 4 | 4 | 21.21 | 4.75 | 4.70% | + | + | nucl: 9, chlo: 2.5, cyto: 2, chlo_mito: 2 | |

| SpCML21 | 107015792 | 167 | 36.24 | 4 | 4 | 18.33 | 4.28 | 5.40% | + | + | cyto: 6, mito: 4, nucl: 2, chlo: 1, extr: 1 | |

| SpCML22 | 107005687 | 238 | 35.95 | 4 | 4 | 27.01 | 4.82 | 4.20% | + | + | chlo: 8, extr: 3, nucl: 1, cyto: 1, vacu: 1 | |

| SpCML23 | 107014219 | 141 | 35.71 | 4 | 3 | 16.09 | 4.43 | 5.70% | + | + | cyto: 10, nucl: 2, cysk: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML24 | 107009143 | 193 | 35.46 | 4 | 4 | 21.67 | 7.69 | 7.30% | + | + | chlo: 7, mito: 4, nucl: 2, pero: 1 | |

| SpCML25 | 107023142 | 185 | 35.42 | 3 | 2 | 21.25 | 4.40 | 2.20% | + | + | cyto: 4, chlo: 2, plas: 2, extr: 2, vacu: 2, mito: 1, E.R.: 1 | |

| SpCML26 | 107012744 | 193 | 34.56 | 4 | 3 | 22.34 | 5.33 | 3.60% | + | + | mito: 8, chlo: 3, cyto_nucl: 2, nucl: 1.5, cyto: 1.5 | |

| SpCML27 | 107005592 | 208 | 34.29 | 4 | 4 | 23.72 | 9.01 | 3.80% | + | + | chlo: 7, plas: 3, nucl: 2, cyto: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML28 | 107022660 | 186 | 33.09 | 4 | 3 | 20.66 | 4.70 | 6.50% | + | + | nucl: 11, chlo: 2, extr: 1 | |

| SpCML29 | 107005005 | 197 | 32.41 | 4 | 3 | 22.30 | 4.94 | 8.60% | + | + | extr: 6, nucl: 5, cyto: 1, vacu: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML30 | 107015719 | 214 | 32.03 | 4 | 2 | 23.39 | 4.44 | 2.80% | + | + | nucl: 4, mito: 4, chlo: 3, extr: 2, cyto: 1 | |

| SpCML31 | 107010362 | 230 | 31.54 | 3 | 2 | 26.69 | 5.05 | 3.00% | + | + | chlo: 4, extr: 3, mito: 2, vacu: 2, nucl: 1, E.R.: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML32 | 107010462 | 141 | 30.94 | 4 | 3 | 16.30 | 4.51 | 5.70% | + | + | cyto: 7, nucl: 2, mito: 2, extr: 2, plas: 1 | |

| SpCML33 | 107004057 | 178 | 30.66 | 4 | 3 | 20.11 | 4.89 | 7.90% | + | + | nucl: 7, cyto: 4, mito: 2, extr: 1 | |

| SpCML34 | 107005004 | 198 | 30.66 | 4 | 3 | 21.87 | 4.79 | 5.60% | + | + | nucl: 8, chlo: 2, cyto: 1, mito: 1, extr: 1, golg: 1 | |

| SpCML35 | 107025899 | 221 | 26.36 | 4 | 4 | 25.03 | 4.54 | 3.20% | + | + | extr: 7, chlo: 3, vacu: 3, cyto: 1 | |

| SpCML36 | 107032262 | 230 | 25.93 | 4 | 2 | 26.26 | 4.47 | 3.50% | + | + | + | cyto: 4, chlo: 3, plas: 3, E.R.: 2, mito: 1, vacu: 1 |

| SpCML37 | 107011884 | 159 | 23.78 | 3 | 3 | 17.31 | 4.38 | 4.40% | + | + | cyto: 14 | |

| SpCML38 | 107016285 | 179 | 17.71 | 2 | 2 | 20.18 | 5.04 | 2.80% | + | + | nucl: 7, cyto: 3, plas: 2, chlo: 1, extr: 1 | |

| SpCML39 | 107031954 | 209 | 15.96 | 4 | 3 | 23.43 | 4.95 | 3.30% | + | + | mito: 7, nucl: 4.5, cyto_nucl: 3, chlo: 2 | |

| SpCML40 | 107017051 | 129 | 15.91 | 4 | 2 | 14.79 | 9.46 | 2.30% | + | + | mito: 6, cyto: 4.5, cyto_E.R.: 3, nucl: 2, chlo: 1 | |

| SpCML41 | 107017137 | 159 | 14.85 | 3 | 2 | 18.07 | 4.49 | 2.60% | + | + | cyto_nucl: 7.5, cyto: 7, nucl: 4, extr: 2, cysk: 1 | |

| SpCML42 | 107017114 | 158 | 14.53 | 3 | 2 | 18.11 | 4.25 | 4.40% | + | + | nucl: 4, cyto: 4, chlo: 3, plas: 2, extr: 1 | |

| SpCML43 | 107002660 | 340 | 13.87 | 2 | 2 | 36.05 | 6.30 | 0.90% | + | + | nucl: 12, cyto: 1, plas: 1 | |

| SpCML44 | 107029131 | 211 | 13.50 | 4 | 1 | 24.18 | 5.25 | 0.90% | + | + | chlo: 6, cyto: 2, mito: 2, plas: 2, extr: 1, E.R.: 1 | |

| SpCML45 | 107003124 | 250 | 13.40 | 2 | 2 | 28.25 | 6.43 | 2.40% | + | + | chlo: 6, nucl: 4, extr: 2, cyto: 1, mito: 1 |

aNucl, nuclear; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mito, mitochondria; Extr, extracellular; Cyto, cytosol; Chlo, chloroplast; Plas, plasma membrane; Cysk, cytoskeleton; Golg, Golgi apparatus; Pero, peroxisomes; Vacu, vacuolar membrane

Phylogenetic analysis of SpCaM and SpCML families

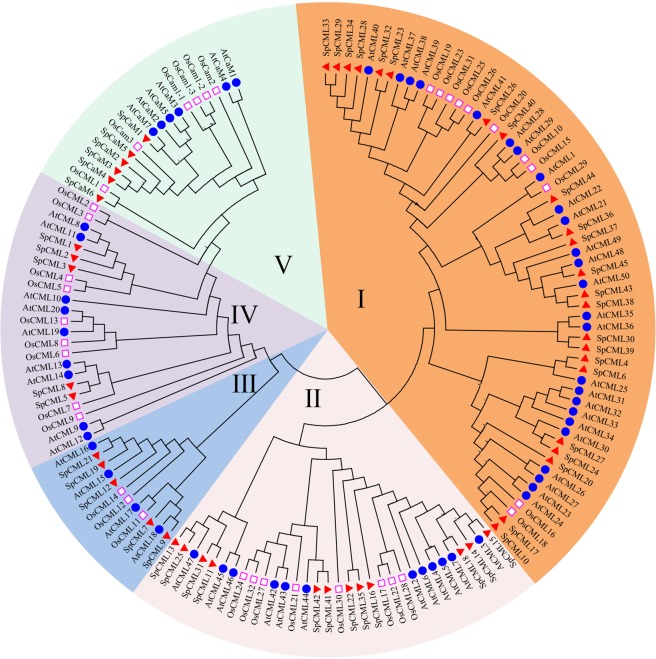

The phylogenetic relationships between the CaM and CML family members of the Solanum pennellii, Arabidopsis, and rice were analyzed using the neighbor-joining method of MEGA6.040. The CaM and CML of the three species were divided into five groups (Fig. 1). The 6, 6, and 5 CaM proteins of the Solanum pennellii, Arabidopsis, and rice, respectively, were individually classified into group V, which was closest to group IV, which was made up of 5 SpCML, 9 AtCML, and 9 OsCML. Only one CML (OsCML-1) existed in group V. In the phylogenetic tree, groups I and III were the largest and the smallest with 59 and 12 CML proteins, respectively. Group I consisted 23 SpCML, 25 AtCML, and 11 OsCML, while group III consisted 5 SpCML, 4 AtCML, and 3 OsCML. Group II consisted 12 SpCML, 12 AtCML, and 8 OsCML.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among CaM and CML proteins from Solanum pennellii, rice, and Arabidopsis. I-V indicated different gene groups. To identify the plant species origin of each CaM and CML, a species acronym was included before the protein name: eg. SpCaM indicated CaM from Solanum pennellii, AtCaM from Arabidopsis and OsCaM from rice. The red triangle, blue dots and pink border square indicated proteins from Solanum pennellii, Arabidopsis and rice, respectively.

The dendrogram showed that the proteins of the Solanum pennellii were generally closer to the proteins of Arabidopsis than those of rice, suggesting the phylogenetic relationship between Solanum pennellii and Arabidopsis is relatively closer.

Genomic distribution of SpCaM and SpCML genes

To determine the distributions of the 6 SpCaM and 45 SpCML on the chromosomes, their physical locations were searched using the NCBI database and were mapped to 12 chromosomes using online MapGene2Chrom program41. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the 6 SpCaM and 45 SpCML were unevenly distributed across the 12 chromosomes. Chromosomes 5, 7, and 8 contained only one gene (SpCML), while chromosome 3 contained the most genes (7 SpCML and 1 SpCaM). Chromosomes 1, 4, and 11 all contained seven genes. The respective number of genes located on chromosomes 2, 6, 9, 10, and 12 were 6, 4, 2, 5, and 2, respectively. The 6 SpCaM genes were distributed on five chromosomes (chromosomes 1, 3, 10, 11, and 12, which contained 1, 1, 2, 1, and 1 gene, respectively. There was only one pair of SpCaM paralogous genes and two SpCaM genes (SpCaM3 and SpCaM4) on chromosomes 11 and 12, respectively. There were two pairs of paralogous genes (SpCML10/SpCML17 and SpCML11/SpCML31) on chromosome 2, while the other two pairs of paralogous genes (SpCML41/SpCML42 and SpCML29/SpCML33) existed on chromosomes 4 and 11, respectively. The other SpCML paralogous genes (SpCML4/SpCML6, SpCML5/SpCML8, SpCML13/SpCML25, SpCML22/SpCML35, SpCML23/SpCML32, SpCML24/SpCML27, SpCML30/SpCML39, and SpCML38/SpCML43) appeared on different chromosomes.

Figure 2.

Locations of SpCaM and SpCML genes on chromosomes. The scale is in megabase (Mb). Paralogous gene are connected by broken red lines.

Genetic structure analysis of the SpCaM and SpCML genes

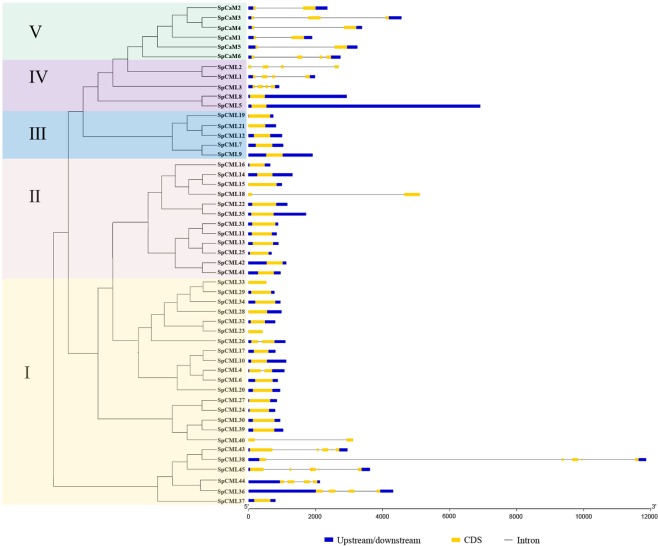

The exon-intron structures of the genes can provide significant evidence to support the phylogenetic relationships within a gene family42, and so genetic structure analysis of the SpCaM and SpCML were carried out using tools available with online website GSDS43,44 (Fig. 3). The analysis of the exons and introns of the CaM and CML genes enabled the genetic structure of these genes to be further understood. Five groups in the SpCaM and SpCML families were observed, which were consistent with the respective corresponding phylogenetic relationships depicted in Fig. 1. Fifteen genes in group I, all members of group II (except SpCML18), and all members of group III contained only one exon each. The SpCML18 gene (group II) contained one intron and two exons, as did SpCML4, SpCML26, and SpCML40 of group I. In group I, SpCML36, SpCML38, SpCML43, SpCML44, and SpCML45 formed a small cluster containing 4-5 exons and 3-4 introns. Group IV was different from the other four groups and could be divided into two subgroups: one subgroup (SpCML1-3) contained four exons and three introns; the other had only one exon and no intron. All SpCaM genes belonged to group V, which involved 2-4 exons and 1-3 introns. Group I and IV genes possessed complex structures, suggesting that gene divergence occurred during evolution.

Figure 3.

The genetic structure of SpCaM and SpCML family members. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the full-length protein sequences of 6 SpCaM and 45 SpCML. Introns and exons of the SpCaM and SpCML genes were grouped according to the phylogenetic classification. Upstream/downstream, exons and introns were represented by blue boxes, yellow boxes, and the black lines respectively.

Conserved motif analysis of the SpCaM and SpCML proteins

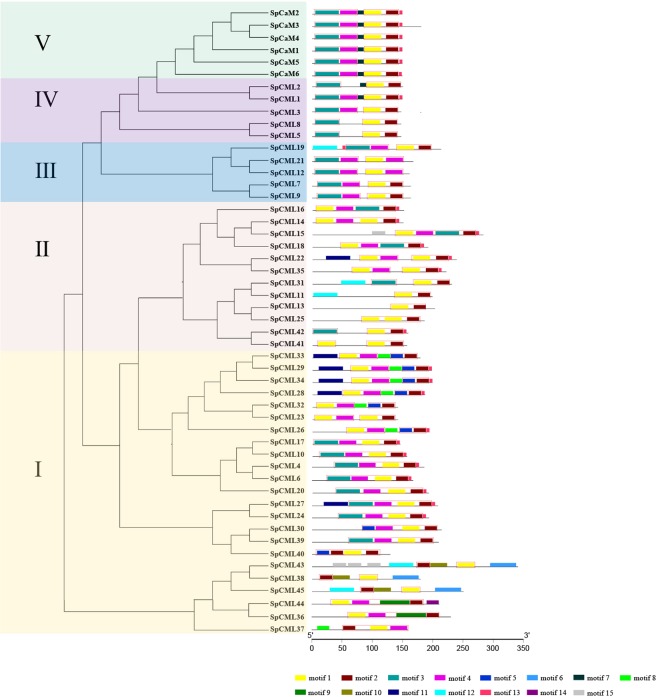

To ascertain the feature sequences of the SpCaM and SpCML protein families, the program MEME45 was used to analyze the conserved motifs of the 51 genes based on their phylogenetic classifications, and 15 conservative motifs were identified in these proteins (Fig. 4, Table 2). The motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 9 were annotated as EF-hand domains by the InterProScan, and the EF-hand domains in motifs 1 and 3 were more complete than those in motifs 5 and 9 (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 4, in addition to SpCML2, SpCML8, SpCML5, SpCML25, SpCML31, SpCML37, SpCML41, and SpCML42 lacked a EF-hand domain, and SpCML11, SpCML13, SpCML38, SpCML45, and SpCML43 lacked two EF-hand domain, the remaining SpCML and SpCaM all contained four EF-hand domain. The degenerate EF-hands in SpCML did not correspond to motif 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15.

Figure 4.

The conserved motifs of SpCaM and SpCML proteins. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the full-length protein sequences of 6 SpCaM and 45 SpCML. The conserved motifs of SpCaM and SpCML proteins were grouped according to the phylogenetic classification. All motifs were identified by MEME. The motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 9 were annotated as EF-hand domains. EF-hands were marked in red border rectangle.

Table 2.

The amino acid sequence of conserved motifs of SpCaM and SpCML proteins.

| Motif No. | Amino acid sequencea |

|---|---|

| motif1 | LKEAFKVFDKDGBGYISAAELRHVLKNLG |

| motif2 | CKEMIREVDVBGDGVINFEEF |

| motif3 | LTDDQJSELKEAFSLFDKBGDGKITTEELGTVLRSLGQNP |

| motif4 | EEELZDMINEVDABGBGFIDFEEFLNLMA |

| motif5 | GYITPKELKSVLSRLGESQGI |

| motif6 | EYDNFIECCLTVKGLTEKFKEKDTSYSGSATFTYDSFMLTILPF |

| motif7 | RKMKDTDSEEE |

| motif8 | IEEERBKESDLREAFNVFDQE |

| motif9 | IGSPELEATFNTIVEAFLFLDKNGDGKLHKKDVLKALNDECPCEKSPSHV |

| motif10 | QKALSSYNQSFGLRTVHLLMYLFTNTNAR |

| motif11 | STAEKESFFSRLRNMFHLKKKEDEKKTTESATTTTTTSTST |

| motif12 | MEPSNSLNRPNYKKFPHHTQPVPLLIHGASGFFFLYIIFDP |

| motif13 | KVMMAR |

| motif14 | WVGIDTDDEKGRLRATTTPQP |

| motif15 | PPSWFGQKPPQSRSPAPPQPSPV |

aThe amino acid sequence of EF-hands are underline by black line.

The motif structures of the SpCML proteins in groups I and II showed diversity and complexity. All SpCML proteins from group I, except for SpCML40, SpCML43, SpCML38, and SpCML45, contained motifs 1, 2, and 4; motifs 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 14 occurred only in group I. Motifs 11 and 15 appeared only in groups I and II, and only in two genes, SpCML43 (group I) and SpCML15 (group II) contained motif 15. Five SpCML, including SpCML43 (group I), SpCML45 (group I), SpCML11 (group II), SpCML31 (group II), and SpCML19 (groupIII), harboured motif 12. Only SpCML19 in group III contained motif 13. In group IV, motifs 4, 7, and 13 occurred simultaneously in SpCML1. However, the structures of the SpCaM proteins were more regular in group V; these proteins contained motifs 7 and 13 in addition to the four EF-hand domains. Although some paralogous proteins contained distinct motif structures, such as SpCML23/32, SpCML30/39, SpCML38/43, and SpCML41/42, most paralogous proteins exhibited similar motif structures, including SpCML4/6, SpCML5/8, SpCML10/17, SpCML11/31, SpCML13/25, SpCML22/35, SpCML24/27, SpCML29/33, and SpCaM3/4.

Taken together, these results revealed that all identified proteins carried typical EF-hand domains, and each subgroup shared similar motif features. These results further support the phylogenetic classifications of the SpCaM and SpCML families.

Cis-Element analysis of SpCaM and SpCML genes

To investigate the mechanisms of the stress-induced gene expression, the online database PlantCARE46 was used to analyze the cis-elements of the 2000 bp upstream sequences of the promoter regions for the SpCaM and SpCML gene coding sequences (Table 3). The results revealed that cis-acting elements associated with responses to phytohormones, such as abscisic acid (ABRE), salicylic acid (TCA-element and W-box), gibberellin (GARE-motif), methyl jasmonate (CGTCA-motif), ethylene (ERE) and auxin (TGA-element); adversity, such as anoxia stress (ARE), low temperature (LTR), light (Sp1 and I-box), drought (MBS), dehydration (DRE); and defense and stress-related elements (TC-rich repeats) occurred widely in the promoter regions of the SpCaM, and SpCML. 78.4% of the 51 genes contained ARE, while 72.5% contained ABRE, and 70.6% contained CGTCA-motif and ERE. Other cis-elements (W-box, MBS, I-box, TC-rich repeats, TCA-element, TGA-element, LTR) accounted for a relatively small proportion of these genes, about 30 to 58%. In addition, there were three cis-elements that accounted for less than 18%, including the GARE-motif (17.6%), DRE (7.8%), and Sp1(2.0%). The fact that SpCaM and SpCML genes had the same or different cis-acting elements suggested that these genes may be simultaneously regulated in response to stress sometimes, or specifically regulated at other times when plants resist adverse external environments. These genes are involved in responses to different stresses.

Table 3.

Cis-element analysis in the promoter regions of the Solanum pennellii SpCaM and SpCML proteins.

| Gene family | Gene name | cis-acting element | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRE | ARE | CGTCA-motif | DRE | ERE | GARE-motif | I-box | LTR | MBS | Sp1 | TC-rich repeats | TCA-element | TGA-element | W-box | ||

| CaM | SpCaM1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| SpCaM2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCaM3 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCaM4 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCaM5 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCaM6 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| CML | SpCML1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| SpCML2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML3 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML4 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML5 | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| SpCML6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML8 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML9 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML11 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML12 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML14 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML15 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML17 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML18 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML19 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| SpCML20 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML21 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML22 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML23 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML24 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML25 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML26 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| SpCML27 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| SpCML28 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML29 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| SpCML30 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML31 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML32 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML33 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| SpCML34 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML35 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML36 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML37 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML38 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| SpCML39 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML40 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML41 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML42 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML43 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| SpCML44 | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| SpCML45 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Total | 37 | 40 | 36 | 4 | 36 | 9 | 21 | 17 | 26 | 1 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 29 | |

Expression of SpCaM and SpCML genes in different tissues

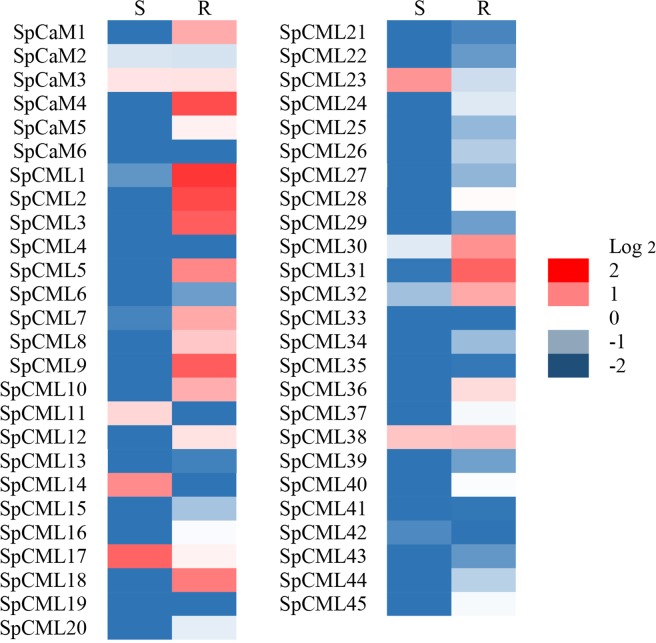

As shown in Fig. 5, transcripts of 51 genes were tested in all tissue samples, which revealed various expression levels of genes. Heat map displayed the expression level of the SpCaM and SpCML genes in stems (S) and roots (R) relative to leaves (Log2 = 0). One SpCaM and two SpCML genes—SpCaM3, SpCML17, and SpCML38—were upregulated in both stems and roots. SpCML14, SpCML17, and SpCML23 showed high expression levels in stems. And SpCaM1, SpCaM4, SpCML1, SpCML2, SpCML3, SpCML5, SpCML7,SpCML9, SpCML10, SpCML18, SpCML30, SpCML31, and SpCML32 were also highly expressed in roots. The tissue-based expression results indicated that SpCaMs and SpCMLs showed the specificity of gene function during plant growth and development.

Figure 5.

The expression heat map of the SpCaM and SpCML genes in stems (S) and roots (R) relative to leaves (Log2 = 0).

Expression of SpCaM and SpCML genes to abiotic stress and hormone treatments in different tissues

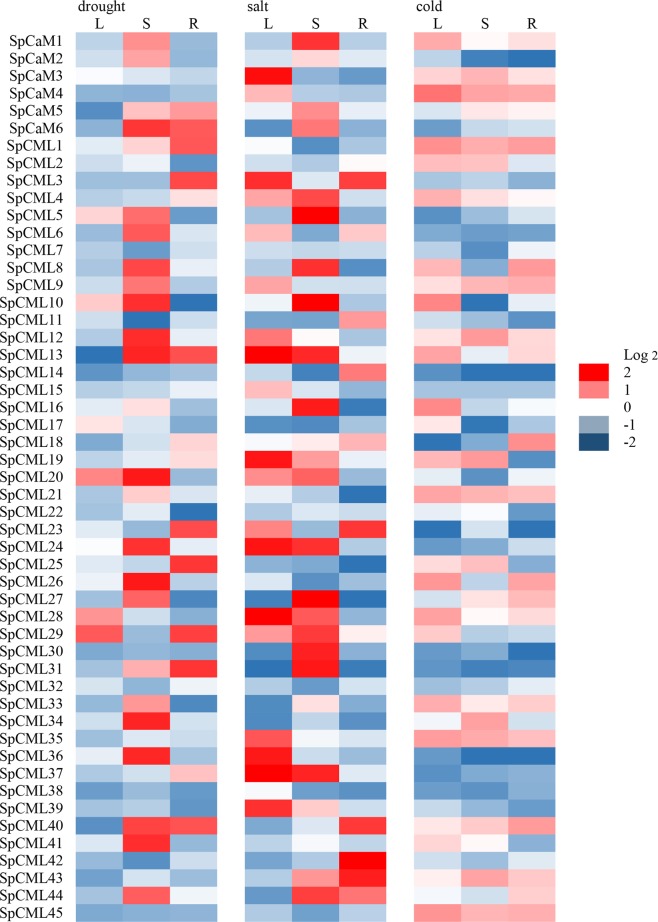

The results showed that all SpCaM and SpCML genes were expressed under cold, drought, and salt stress, but exhibited disparate relative expression levels in different tissues following stress treatments (Fig. 6). In leaves, 6, 19, and 25 of the 51 genes showed high expression (Log2 > 0) under drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively. In stems, 25, 25, and 21 genes were upregulated (Log2 > 0) under drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively. In roots, 14, 12, and 21 genes were induced (Log2 > 0) under drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively. Remarkably, in leaves, drought and cold stress induced strong expression of only one gene each (Log2 > 1), namely SpCML29 and SpCaM4, respectively, whereas 11 genes (SpCaM3, SpCML3, SpCML12, SpCML13, SpCML19, SpCML24, SpCML28, SpCML35, SpCML36, SpCML37, and SpCML39) were strongly expressed (Log2 > 1) in leaves under salt stress. Conversely, in stems and roots, no genes were obviously upregulated (Log2 > 1) under cold stress. However, 17 genes showed strong expression (Log2 > 1) under drought and salt stress respectively, in stems. Nine and seven genes were also overexpressed (Log2 > 1) under drought and salt stress, respectively, in roots. On the whole, the total number of strongly upregulated (Log2 > 1) genes were higher in stems than in leaves and roots. In addition, under cold stress, 14 genes (SpCaM1, SpCaM3, SpCaM4, SpCML1, SpCML4, SpCML9, SpCML12, SpCML21, SpCML28, SpCML33, SpCML35, SpCML40, SpCML43, and SpCML45) were upregulated simultaneously (Log2 > 0) in leaves, stems, and roots. But, this phenomenon did not appear under salt and drought stress.

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of the SpCaM and SpCML genes under abiotic stress in different tissues. S: stems, R: roots, L: leaves.

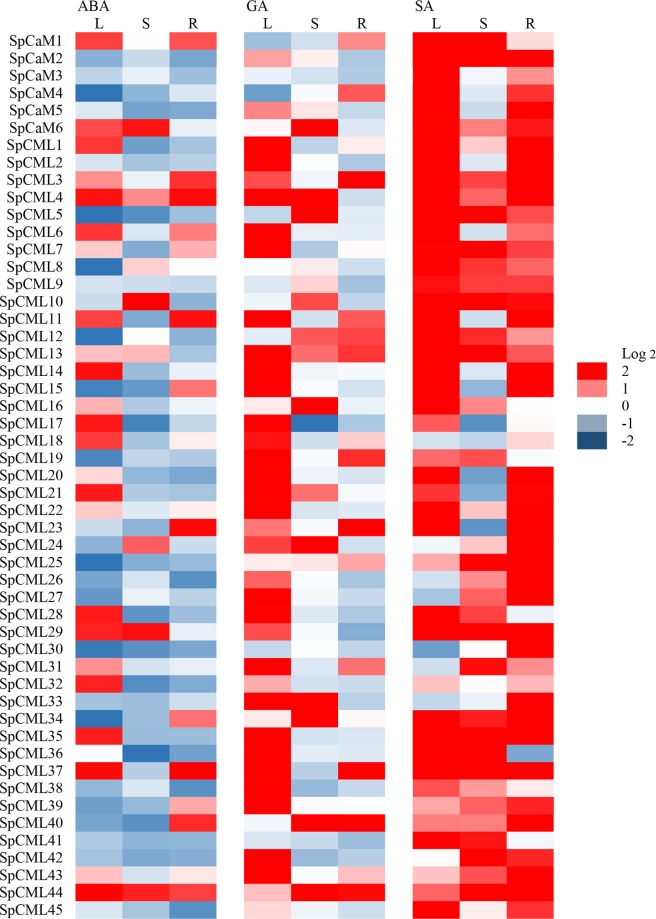

The expression levels of SpCaM and SpCML genes under ABA, GA, and SA treatments are depicted in Fig. 7. ABA treatment upregulated (Log2 > 0) 24, 8, and 16 genes in leaves, stems, and roots, respectively. GA treatment induced (Log2 > 0) 40, 19, and 18 genes in leaves, stems, and roots, respectively. SA treatment upregulated (Log2 > 0) 44, 37, and 46 genes in leaves, stems, and roots, respectively. These results indicated that a higher number of SpCaM and SpCML genes were upregulated in response to SA than in response to ABA and GA. Notably, in leaves, 16, 31, and 39 genes showed strong expression (Log2 > 1) upon ABA, GA, and SA treatments. In stems, 5, 13, and 28 genes were strongly induced (Log2 > 1) by ABA, GA, and SA treatments. In roots, 11, 11, and 38 genes were also overexpressed (Log2 > 1) by ABA, GA, and SA treatments. Thus, the total number of strongly upregulated genes was higher in leaves than in stems and roots. The analysis also showed that 27 genes were induced simultaneously (Log2 > 0) in leaves, stems, and roots by SA treatment, while 2 (SpCML4 and SpCML44) and 4 genes (SpCML13, SpCML25, SpCML34, and SpCML44) were upregulated simultaneously in leaves, stems, and roots, respectively, by ABA and GA treatments. These results suggested that SpCaM and SpCML genes may be associated with plant resistance to abiotic stress and regulatory hormones and that different members may play different roles in response to different stimuli.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of the SpCaM and SpCML genes under hormone treatments in different tissues. S: stems, R: roots, L: leaves.

Discussion

Ca2+, as a multifunctional signaling molecule, is at the core of complex antistress signaling pathways in response to adverse environmental conditions47. Calmodulin (CaM) is the main calcium sensor in all eukaryotes and can sense changes in the concentration of Ca2+. Change of intracytoplasmic free Ca2+ level is the earliest response of cells to various abiotic and biological stresses5. Recent studies have found that CaM and CMLs are key components of stress signal transduction. For instance, heat shock proteins (HSPs) induced by high temperatures are regulated by heat shock transcription factors (HSFs). HSFs are activated by phosphorylation of protein kinases. Compared with wild type, the activity of HSFs in the AtCaM3 mutant was decreased, which inhibited the biosynthesis of HSPs and reduced the heat resistance of plants48. The overexpression of the soybean GmCaM4 gene activates the pathogenesis-related (PR) gene and accumulates jasmonic acid (JA), which increases soybean resistance to the oomycete Phytophthora sojae, Alternaria tenuissima and Phomopsis longicolla. However, the silencing of the GmCaM4 gene significantly inhibited the expression of the PR gene49. MYB2 (CaM binding transcription factor) contains a Ca2+-dependent CaM binding domain and regulates the expression of salt and dehydration response genes in Arabidopsis50. It has been confirmed that the interaction of GmCaM4 and MYB2 regulates the expression of salt-responsive genes and improves tolerance to high-salt environments49. AtCML42 mutant increases the expression of JA responsive gene, thus enhancing the plant defense against herbivorous insects. In addition, JA-induced Ca2+ elevation and root growth inhibition are more pronounced in AtCML42 mutants. The above results indicate that AtCML42 is an important component connecting Ca2+ and JA signals, and plays a negative regulatory role. AtCML42 is also involved in abiotic stress responses. AtCML42 mutant decreases resistance to ultraviolet radiation B (UV-B) and accumulates abscisic acid content under drought stress51. The difference is that the accumulation of JA in ATCML37 mutants is significantly reduced, which indicated ATCML37 plays an active regulatory role in Ca2+ signaling pathway52. These data suggest that CaM and CML mediate multiple defense signaling pathways. Solanum pennellii possesses excellent resistance to stress, which is an important germplasm resource to cultivate high-quality tomato53. However, the structural characteristics of CaM and CML genes and their responses to various stresses have not been systematically studied in Solanum pennellii. In this study, we identified and systematically analyzed the two families.

We identified 6 CaM and 45 CML from the Solanum pennellii genome sequence. This is roughly consistent with the number of genes identified in other plant species previously reported, such as Arabidopsis9, Oryza sativa13, Gossypium raimondii11, and Nicotiana Benthamiana8 (Table 4). The results showed that there were differences in the number of genes in CaM and CML families (Table 4). The differences in sizes of genes in these families may be due to their ploidy levels and their involvement in different vital cellular processes. In principle, adding or evolving more genes or genomes is the inevitable result of and the correct direction for plant evolution. This phenomenon may occur because ecological strategies of different plants to cope with different environments are related to the adaptation and expansion of gene families54–56. Over the course of evolution, variations in gene family size are mainly caused by natural variation in different species and their adaptation to complex growth environments56,57.

Table 4.

The number of CaM and CML in different species.

| Species | Protein type | |

|---|---|---|

| CaM | CML | |

| Solanum pennellii | 6 | 45 |

| Arabidopsis | 6 | 50 |

| Rice | 5 | 32 |

| Gossypium raimondii | 6 | 30 |

| Nicotiana Benthamiana | 7 | 55 |

As a result of the abundant selective splicing of genes and the post-translational modification of proteins, the functional and chemical complexity of proteins is enhanced. The post-translational modification event myristoylation has extremely diverse biological functions associated with signal transduction, protein transport, protein localization, extracellular communication, and protein regulation and metabolism. The analysis showed that SpCaM was without myristoylation sites (Table 1). Palmitoylation and myristoylation are sometimes interrelated and interdependent, and the absence of myristoylation may lead to the disappearance of palmitylation58.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed to understand the evolution of SpCaM and SpCML (Fig. 1). The SpCaM and SpCML were classified into five groups (I, II, III, IV, and V). The results showed that CML groups (I, II, III, IV) dominated the phylogenetic tree. SpCaM and SpCML evolved together from their common ancestors, and these SpCML evolved before SpCaM. This is why there are more SpCML genes than SpCaM genes in the genome, and SpCML genes were diversified more. Location analysis of these 51 genes on the chromosome revealed that these genes were not evenly distributed on the chromosome (Fig. 2). Chromosomes 3 had the most genes (8 genes), followed by chromosomes 1, 4, and 11 (7 genes each) and chromosome 2 (6 genes). Chromosomes 1, 3, 10, 11, and 12 contained both CaM and CML genes (Table 5).

Table 5.

The number of genes on the chromosomes of Solanum pennellii.

| Gene name | Chrom 1 | Chrom 2 | Chrom 3 | Chrom 4 | Chrom 5 | Chrom 6 | Chrom 7 | Chrom 8 | Chrom 9 | Chrom 10 | Chrom 11 | Chrom 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaM | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| CML | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 45 |

| Total | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 51 |

The conserved motif and gene structure analyses of SpCaM and SpCML genes showed that each group shared similar exon-intron structures and motifs, which provided further evidence for their classification (Figs. 3 and 4). Gene structure analysis showed that most SpCML genes lacked introns, while SpCaM contained only one long intron (Fig. 3); these findings were in accordance with findings on the exon-intron structure of CaM and CML genes in Arabidopsis9, Nicotiana benthamiana8, Brassica rapa L.16, and Solanum tuberosum8. However, some SpCML genes contained 1, 3, or 4 introns. At present, studies on the evolution of introns have found that intron loss is more likely to occur than intron gain during evolution59. Based on these insights, it can be hypothesized that the majority of SpCML without introns are older than SpCaM. The few SpCML genes with introns possibly evolved from their closest SpCaM. This explains why group IV SpCML and group V SpCaM are the closest in the evolutionary tree (Fig. 1). The conserved motif is also a key index to evaluate protein function60. The exon-intron distribution analysis reflected the conservatism and functional differences among different proteins. Conserved motif analysis suggested all SpCaM proteins contain 4 EF-hand type calcium-binding domains, and all SpCML contain at least 1 EF-hand type calcium-binding domain (Fig. 4).

qRT-PCR analysis of SpCaM and SpCML indicated that the expression levels of SpCaM and SpCML genes were affected in Solanum pennellii under abiotic stress and hormone treatments. The expression profiles of SpCaM and SpCML genes in different tissues showed different expression levels of SpCaM and SpCML genes (Fig. 5). The SpCaM4, SpCML1, SpCML2, SpCML3, SpCML9, SpCML18, and SpCML31 showed significantly higher expression level (Log2 > 1) in roots than in other tissues, while expression level of SpCML17 in stems was significantly higher (Log2 > 1) than in other tissues, suggesting that different SpCaM and SpCML gene members have distinct expression levels in various tissues. The diversified expression of these SpCaM and SpCML genes revealed that they might play a significant role in different plant tissues61.

The expression levels of SpCaM and SpCML genes under abiotic stress and hormone treatments in different tissues indicated that the expression of SpCaM and SpCML genes were affected (Figs. 6 and 7). Under cold stress, the expression of SpCaM4 in leaves was significantly increased (Log2 > 1), while down-regulation of SpCaM4 expression was found under ABA treatment, revealing that SpCaM4 may be involved in Ca2+ transport under cold stress. The results are not entirely consistent with previous studies. Delk et al. found Arabidopsis CML24 was expressed in all major organs and upregulated under cold stress and ABA treatment62. It is has been reported that AtCML9 was induced under salt stress and ABA treatment, and involved in salt stress tolerance by affecting ABA-mediated pathways63. In Solanum pennellii, the expression levels of 11 genes were obviously upregulated (Log2 > 1) under salt stress, ABA and GA treatments, including 3 (SpCML28, SpCML35 and SpCML37), 4 (SpCaM6, SpCML10, SpCML24 and SpCML44) and 4 (SpCML3, SpCML23, SpCML40 and SpCML44) genes in leaves, stems and roots. These ten genes might participate in salt stress via ABA and GA-mediated pathway.

Under drought, salt, and ABA treatments, 4 (SpCaM6, SpCML10, SpCML24 and SpCML44) and 3 (SpCML3, SpCML23 and SpCML40) genes in stems and roots showed strong expression (Log2 > 1) (Figs. 6 and 7). The results are consistent with the study by Xu et al. who reported OsMSR2 (Oryza sativa l. multi-stress response gene 2), a novel CML gene, was strongly upregulated under drought and salt stress in different tissues at different stages of development, and enhanced tolerance to salt and drought via ABA-mediated pathway in rice61.

Conversely, Arabidopsis AtCML37, AtCML38, and AtCML39 showed greater sensitivity to drought and salt than to ABA and SA, suggesting that these proteins may act as Ca2+ transducers in signaling pathways independent of ABA and SA64. OsCML4 confers drought tolerance through ROS-scavenging in an ABA independent manner in rice65. This phenomenon also exists in this study. The expression of the SpCML20 gene in stems was significantly induced (Log2 > 1) under drought and salt than under ABA and SA (Figs. 6 and 7). These results suggested that SpCaM and SpCML genes have diverse functions in different tissues in response to different stimuli, and may play a role as stress response genes to improve stress tolerance.

In this study, a total of 6 CaM and 45 CML genes were identified in the Solanum pennellii genome. These 51 genes were unevenly located on 12 chromosomes. SpCaM and SpCML were classified into five groups via phylogenetic analysis. Further analysis of their conserved motifs and gene structure revealed their evolutionary relationship, wherein it was suggested that SpCML evolved earlier than SpCaM. Analysis of cis-acting elements of these genes implied that they play crucial roles in response to multiple signaling pathways related to stress resistance. This study provides important insights into the evolution and function of Solanum pennellii genes, which lays a good foundation for the genetic improvement of stress-resistant tomato cultivars.

Materials and Methods

Identification of SpCaM and SpCML

All CaM and CML protein sequences of Arabidopsis and rice were obtained from the TAIR database (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and rice Database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), respectively. The whole protein and nucleotide sequences of Solanum pennellii33 were obtained from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/).

Phylogenetic analysis and chromosomal localization

CaM and CML protein sequences of Arabidopsis (6 and 50, respectively)12 and rice (5 and 32, respectively)13 and SpCaM and SpCML protein sequences of Solanum pennellii were aligned by the MUSCLE program of MEGA6.040, with default settings. Then, phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method of MEGA6.0, in which bootstrap value was set to 1000. The chromosomal location information of 51 genes of Solanum pennellii was obtained from the NCBI database. The online MapGene2Chrom program was used to map their chromosomal locations (http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0/)41.

Sequence analysis

Physicochemical parameters of SpCaM and SpCML proteins, including theoretical isoelectric point (pi), molecular weight, amino acid sequence length (AA), and the N-terminal myristoylation were predicted using the ExPASy proteomics server (http://web.expasy.org/myristoylator/), with default settings38. The ScanProsite tool of ExPASy was used to retrieve the EF-hand domain, and calcium-binding region. The subcellular localization of proteins was predicted using the Wolf PSORT (http://www.genscript.com/psort/wolf_psort.html) program39. The structure of these genes was analyzed using tools available with online website GSDS (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/)43,44. Genomic DNA sequences of SpCaM and SpCML were downloaded from the NCBI database.

Conserved motif analysis

The MEME suite (http://alternate.meme-suite.org/tools/meme) was used to identify 15 conserved motifs. These conserved motifs were further annotated with InterProScan45.

Cis-acting element analysis

The starting site of SpCaM and SpCML nucleotide sequences on chromosomes were searched in NCBI. The upstream 2000 bp sequences of SpCaM and SpCML genes, as the promoter region, were obtained using the same method, and then the database PlantCARE was used to analyze the cis-acting elements in the promoter region (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/)46.

Plant materials

In this study, wild cultivar Solanum pennellii LA0716 was used. The seeds were placed on moist filter paper in a petri dish, then the petri dish was transferred to a constant temperature incubator at 27 °C without light for 3 days. The germinated seeds were transplanted into 1/2 full nutrient solution66. All plants were grown in a 26 °C/19 °C (day/night) greenhouse at approximately 70% relative humidity and incubated for 30 days.

Abiotic stress and hormone treatments

Thirty-day-old seedlings were used to explore the responses of the plant to abiotic stress and hormone treatments. For cold stress, salt stress and drought stress, the seedlings were respectively placed in 1/2 full nutrient solution at 4 °C, with 100 mmol/L NaCl, and with 10% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000. Drought stress was simulated by decreasing osmotic potential. For the hormone treatments, the seedlings were respectively grown in 1/2 full nutrient solution with 150 µmol /L gibberellic acid (GA), with 100 mmol /L abscisic acid (ABA), and with 100 µmol/L salicylic acid (SA). The seedlings were collected at 1 h after treatments. All the treatments collected three biological samples, which were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR assays

TRIzol reagent (Tianmo biotech, Beijing, China) was used to extract total RNA from the roots, stems, and leaves according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, DNase I treatment was used to removing genomic DNA contamination from total RNA. Two micrograms of total RNA were used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis using the 5X All-In-One RT MasterMix (with AccuRT Genomic DNA Removal Kit) (Applied Biological Materials, Zhenjiang, China). For qRT-PCR analysis, the reactions were performed using the Bestar® Sybr Green qPCR Master Mix (DBI, Shanghai, China) in an ABI7500 qRT-PCR system according to the manufacturer’s instructions The primers used for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table 6. For all analyses, actin was used as an internal control. Three technological replicates of each sample were assayed. The relative quantification of specific mRNA levels was calculated from the cycle threshold (Ct) using the 2−ΔΔCt method67.

Table 6.

Primers used in qRT-PCR analysis.

| Gene Name | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Gene Name | Forward primer | Rever Se primer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCaM 1 | GGATCAAAATGGCTTCATCTCC | CCATCAACATCAGCTTCCCTAA | SpCML21 | CTACATTACCGCCGCTGAAC | CGGAGACGTTATTTAATCCGAGA |

| SpCaM 2 | ATGGCAGATCAGCTCACCG | CCAACGACCTCATCACAGTCC | SpCML22 | ATGAATGAAGAAGAAGTTGCTAA | TTACAATGATCCAATTTCTTACC |

| SpCaM 3 | AGAGGTTGATGAGATGATTCGTG | CTTTTCTTCCATTGCTCTGTGA | SpCML23 | GTAGAAGATGGAGGGACGAAAGA | TCTTCTCCCCTAACCTATGAAGC |

| SpCaM 4 | ATGGCGGATCAGCTTACAGA | GATTTTGTCCCAGCGAACG | SpCML24 | GTAAAGCAAACGCCAAGCAC | TCATCGCCGATTTGTATTCC |

| SpCaM 5 | AACTTGGAACTGTAATGCGGTCA | CCCATTTCCATCAGCATCAAC | SpCML25 | TTCTTGGATTTATCGGTGTTCG | AAGATATGCTCGATGAGCTTGAC |

| SpCaM 6 | AGGATGGCGATGGCTGTATT | TGTCCTTCATCTTCCGTGCC | SpCML26 | CAAAGTCTTCAAATTCAAGCCAA | TACCATCGTTATCGGTGTCAAA |

| SpCML1 | TCCAACAGAGGAAGAACTGCC | GCTTGTCAAACACCTTGAAAGC | SpCML27 | GGGGAAGAAGAACCTCCTCAC | AGGCACTCTGCAAATCCGTAG |

| SpCML2 | AAGGTCATTGGATGAAAATCCA | GTTCTTCCTCTAAATCCGTCTCC | SpCML28 | AGTAGTAGCGAAAATAGCGATCAA | ATCCTCTAACCCTAACATCCCAT |

| SpCML3 | AAAATCCAACAAGGGAAGAGC | CCGTTACATTGTCCTTGAGCT | SpCML29 | TAGTTTCTGTTTCCATGGCTGAA | CACTCTCATGTTCCTTCTTAGGAGT |

| SpCML4 | ACGATAATCCAATGCCTGTGAA | GGACCCTAATTCCGATGAACATA | SpCML30 | TACGAGCGTGTTACCTACTTTATCC | TCCTCTTCACTCGGTGGAGATT |

| SpCML5 | CATAATCGCCGAGGAGAAAC | CGAGGACCTTAAAGGCATCA | SpCML31 | TCCAGTTCCCCTGCTAATTCAT | GCCATAACCATTTCCACCTCTT |

| SpCML6 | AGAGGAGCTACAACAAGTATTCAAC | CTCTGTTACAGCGGTTCCTAAAC | SpCML32 | AAAGGCTGCTGTTGAGCATAAT | CACCCTTCCATTTCATACATCTTG |

| SpCML7 | GATAGGGACGGTAATGGTGTGA | GAAGTCATCGCCTGAGCAAAC | SpCML33 | ACAACAGCAACAACAACCACCA | CCCATCTCCGTTCTCATCAAAG |

| SpCML8 | CATTTGATCGCCAATTACGC | GAAATCTTCATACCGGATCTTACC | SpCML34 | GGAGATGGAAAGGTGTCACCTG | TAAAATCCTCAATGCCCAATAAT |

| SpCML9 | TTTGATAGGGATGGAAATGGTTA | CCGAAGAAATCGCCTGAGTAA | SpCML35 | CTCTCTGTTAAACCTCAAACCCTAA | ATCTCCATCTTCCATAAAAATCCC |

| SpCML10 | AACTCCCAGCGACTCCAAAC | GACGTCTTACTGCCAAGTGCA | SpCML36 | CTCTAGTCCCAAGGCTTCTATCC | GCTCCGTTGCTGTCTTCATC |

| SpCML11 | CCGTTAGTACCGTTCCTGTTCC | CACATTATGGTGGGATGTTGTTG | SpCML37 | AGTGTTTTGCATTCTGCCGG | GTCATCATCGTACCAATCATATCGT |

| SpCML12 | CGGGCGATCAAATCCATACA | GCAGCCGTTATATAACCGTTACC | SpCML38 | GTCAAGGGACTGACGGAGAAAT | AGCAATGAGGAAAGGCAGAATA |

| SpCML13 | TTCATCATTGTGCGAAACGC | CTCGAAACCTCTGCATACTCTGTT | SpCML39 | GCAGAGTCGGAACTGAACCA | GGTCCAAACGCTGAGCTAATAG |

| SpCML14 | AATGGAAGAGCGAGATGAGGAG | GACCAAGTGATGCCAAGACAGA | SpCML40 | TGGCGATGGACGTATTGATATG | CGGAATGCCTCCGTGAGAT |

| SpCML15 | ATGTGAATGGAGACGGTTGC | AGCCCTAACGATGCGAGAAC | SpCML41 | TTGGTAAAACAAGCCTAGACTTCA | CAGCTCCTCACAACATATGAATCC |

| SpCML16 | CAATGAACGAGCTAAATGATTCG | GTTGAATGCCTCTTGCATGTCTT | SpCML42 | AGATGATCTTGTTGAAGCATTCAAG | CTTACAATCACTTCCTTCTTTCTCA |

| SpCML17 | AGCGAATGATGCTAGAGGTTGA | CTCTCCAATGCCTTTCATAACG | SpCML43 | CCACTCACAACCGTCTGCTC | CATCAATTAACCCACTCCCATC |

| SpCML18 | TTTTGTCATCGTTGGGTTTGAA | CCACCACGTTTCATCATTTGTCT | SpCML44 | AGGGGTTGAAGGAGATAAAAGAC | TTCATCCACATCACAAGAGTCG |

| SpCML19 | TTCTAATGGAAATGGGTCTGTGG | TCTCGATACGACAATGGCTGAC | SpCML45 | ACCCAAATGAGCCACCAATAG | AAGAACCAGGTCCATAACCAGC |

| SpCML20 | GATTGATACAAATGGGGATGGA | CTGCTAATTCTTCAGCAGCTTTC | Actin | ATTCAGCCCCTTGTTTGTGAC | CATAGGCATCCTTCTGTCCCAT |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Beijing innovation team construction project (25018004). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: J.S. and X.D. Performed the experiments: J.S. Analyzed the data: J.S. Wrote the paper: J.S. Provided guidance on the whole study: J.S and X.D.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gilroy S, Trewavas A. Signal processing and transduction in plant cells the end of the beginning. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:307–314. doi: 10.1038/35067109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders, D. et al. Calcium at the Crossroads of Signaling. The Plant Cell14 (suppl 1) (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Harper JF, et al. Plants, symbiosis and parasites: a calcium signalling connection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6(7):555–566. doi: 10.1038/nrm1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandelle E, et al. Identification, characterization, and expression analysis of calmodulin and calmodulin-like genes in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) reveal likely roles in stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;129:221–237. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blume B, et al. Receptor-mediated increase in cytoplasmic free calcium required for activation of pathogen defense in parsley. Plant Cell. 2000;12(8):1425–40. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudsocq M, Sheen J. CDPKs in immune and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy AS, et al. Coping with stresses: roles of calcium- and calcium/calmodulin-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell. 2011;23(6):2010–2032. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and functional analyses of calmodulin genes in Solanaceous species. BMC Plant Biology. 2013;13:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormack E, et al. Handling calcium signaling: Arabidopsis CaMs and CMLs. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(8):383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranty B, et al. Calcium sensors as key hubs in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:327. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohanta TK, et al. Genomics and evolutionary aspect of calcium signaling event in calmodulin and calmodulin-like proteins in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-0989-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormack E, Braam J. Calmodulins and related potential calcium sensors of Arabidopsis. New Phytologist. 2003;159(3):585–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boonburapong B, Buaboocha T. Genome-wide identification and analyses of the rice calmodulin and related potential calcium sensor proteins. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munir S, et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of calmodulin-like (CML) proteins in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;102:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng H, et al. Analysis of EF-Hand proteins in soybean genome suggests their potential roles in environmental and nutritional stress signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:877. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie S, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calmodulin-like (CML) genes in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):842. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinpongpanich A, et al. Expression analysis of calmodulin and calmodulin-like genes from rice, Oryza sativa L. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5:625. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu XY, et al. CaM and CML emergence in the green lineage. Trends in Plant Science. 2015;20(8):483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poovaiah BW, et al. Recent advances in Calcium/Calmodulin-mediated signaling with an emphasis on plant-microbe interactions. Plant Physiology. 2013;163(2):531–542. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheval, C. et al. Calcium/calmodulin-mediated regulation of plant immunity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research1883(7), 1766-1771 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Perochon A, et al. Calmodulin and calmodulin-like proteins in plant calcium signaling. Biochimie. 2011;93(12):2048–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeFalco, T. A. et al. Breaking the code: Ca2+ sensors in plant signalling. Biochemical Journal425, 27–40 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wang, S. S. et al. Arabidopsis thaliana CML25 mediates the Ca2+ regulation of K+ transmembrane trafficking during pollen germination and tube elongation. Plant Cell Environ. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bender KW, et al. The Arabidopsis calmodulin-like protein, CML39, functions during early seedling establishment. Plant J. 2013;76:634–647. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy VS, et al. KIC, a novel Ca2+ binding protein with one EF-hand motif, interacts with a microtubule motor protein and regulates trichome morphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:185–200. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobney S, et al. The calmodulin-related calcium sensor CML42 plays a role in trichome branching. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31647–31657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaels SD, Amasino RM. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell. 1999;11:949–956. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai YC, et al. Arabidopsis potential calcium sensors regulate nitric oxide levels and the transition to flowering. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2:446–454. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.6.4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, et al. Calmodulin-like gene MtCML40 is involved in salt tolerance by regulating MtHKTs transporters in Medicago truncatula. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2019;157:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghorbel M, et al. The activity of the wheat MAP kinase phosphatase 1 is regulated by manganese and by calmodulin. Biochimie. 2015;108:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiasson D, et al. Calmodulin-like proteins from Arabidopsis and tomato are involved in host defense against Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;58:887–897. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu X, et al. CML8, an Arabidopsis calmodulin-like protein, plays a role in pseudomonas syringae plant immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58(2):307–319. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolger A, et al. The genome of the stress-tolerant wild tomato species Solanum pennellii. Nature Genetics. 2014;46(9):1034–1038. doi: 10.1038/ng.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foolad MR. Genome mapping and molecular breeding of tomato. Int. J. Plant Genomics. 2007;2007:64358. doi: 10.1155/2007/64358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muigai SG, et al. Greenhouse and field screening of wild Lycopersicon germplasm for resistance to the whitefly Bemisia argentifolii. Phytoparasitica. 2003;31:27. doi: 10.1007/BF02979764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, L. et al. Mapping of QTLs for drought tolerance during seedling stage using introgression line populations in tomato. Acta. Horticulturae Sinica. 38 (2011).

- 37.Frary A, et al. Salt tolerance in Solanum pennellii: antioxidant response and related QTL. BMC Plant Biology. 2010;10:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasteiger E. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic. Acids. Research. 2003;31(13):3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horton, P. et al. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Biochimie. 35(Web Server issue), W585–587 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Tamura K, et al. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao JT, et al. MapGene2Chrom, a tool to draw gene physical map based on Perl and SVG languages. Hereditas. 2015;37(1):91–97. doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W, et al. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in Gossypium raimondii. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu B, et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(8):1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiao L, et al. Characterization and expression patterns of auxin response factors in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1395. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown P, et al. MEME-LaB: motif analysis in clusters. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(13):1696–1697. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lescot M, et al. PlantCARE: a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2002;30(1):325–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antony N, et al. The Language of Calcium Signaling. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010;61:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-070109-104628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, et al. Molecular and genetic evidence for the key role of AtCaM3 in heat-shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1773–1784. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rao SS, et al. Overexpression of GmCaM4 in soybean enhances resistance to pathogens and tolerance to salt stress. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014;15:145–160. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoo JH, et al. Direct interaction of a divergent CaM isoform and the transcription factor, MYB2, enhances salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3697–3706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vadassery J, et al. CML42-mediated calcium signaling coordinates responses to Spodoptera herbivory and abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1159–1175. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.198150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scholz SS, et al. Mutation of the Arabidopsis calmodulin-like protein CML37 deregulates the jasmonate pathway and enhances susceptibility to herbivory. Mol. Plant. 2014;7:1712–1726. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rick C, Tanksley S. Genetic variation in Solanum pennellii: comparisons with two other sympatric tomato species. Plant Syst. Evol. 1981;139:11–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00983920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lespinet O, et al. The role of lineage-specific gene family expansion in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2002;12(7):1048–1059. doi: 10.1101/gr.174302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Trends between gene content and genome size in prokaryotic species with larger genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101(9):3160–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308653100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer I, et al. Impact of recurrent gene duplication on adaptation of plant genomes. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo YL. Gene family evolution in green plants with emphasis on the origination and evolution of Arabidopsis thaliana genes. Plant J. 2013;73(6):941–951. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martín ML, Busconi L. A rice membrane-bound calcium-dependent protein kinase is activated in response to low temperature. Plant Physiol. 2001;125(3):1442–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roy SW, Gilbert W. The evolution of spliceosomal introns: patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7(3):211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Day IS, et al. Analysis of EF-hand-containing proteins in. Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2002;3(10):RESEARCH0056. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-reports0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu W, et al. Characterization of a novel stilbene synthase promoter involved in pathogen- and stress-inducible expression from Chinese wild Vitis pseudoreticulata. Planta. 2010;231(2):475–487. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delk NA, et al. CML24, regulated in expression by diverse stimuli, encodes a potential Ca2+ sensor that functions in responses to abscisic acid, daylength, and ion stress. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:240–253. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnan F, et al. Mutations in AtCML9, a calmodulin-like protein from arabidopsis thaliana, alter plant responses to abiotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant J. 2008;56:575–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanderbeld B, Snedden WA. Developmental and stimulus-induced expression patterns of Arabidopsis calmodulin-like genes CML37, CML38 and CML39. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;64:683–97. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin XM, et al. OsCML4 improves drought tolerance through scavenging of reactive oxygen species in rice. J. Plant Biol. 2015;58:68–73. doi: 10.1007/s12374-014-0349-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu HY, Du XG. Differential regulation of calmodulin, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, and salicylic acid in response to Botrytis cinerea infection in tomato with different Ca2C concentrations. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 2018;41(6):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu DG, et al. Overexpression of MdSOS2L1, a CIPK protein kinase, increases the antioxidant metabolites to enhance salt tolerance in apple and tomato. Physiol. Plant. 2016;156:201–214. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]