Abstract

The recent trend of global warming has exerted a disproportionately strong influence on the Eurasian land surface, causing a steady decline in snow cover extent over the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau region. Here we show that this loss of snow is undermining winter convective mixing and causing stratification of the upper layer of the Arabian Sea at a much faster rate than predicted by global climate models. Over the past four decades, the Arabian Sea has also experienced a profound loss of inorganic nitrate. In all probability, this is due to increased denitrification caused by the expansion of the permanent oxygen minimum zone and consequent changes in nutrient stoichiometries. These exceptional changes appear to be creating a niche particularly favorable to the mixotroph, Noctiluca scintillans which has recently replaced diatoms as the dominant winter, bloom forming organism. Although Noctiluca blooms are non-toxic, they can cause fish mortality by exacerbating oxygen deficiency and ammonification of seawater. As a consequence, their continued range expansion represents a significant and growing threat for regional fisheries and the welfare of coastal populations dependent on the Arabian Sea for sustenance.

Subject terms: Climate sciences, Marine biology

Introduction

The Arabian Sea (AS) is a unique, low-latitude oceanic ecosystem because it is influenced by monsoonal winds that reverse their direction seasonally1. These reversing winds cause dynamic shifts in surface currents and alterations in the pycnocline, which help fertilize its normally nutrient-depleted surface layers. However, the mechanisms that drive water-column mixing, the upward transport of nutrients and the consequent upsurge of phytoplankton biomass during the summer (Jun.-Sep.) and the winter (Nov.-Feb.) monsoons are different2–6. During the summer monsoon, nutrient enrichment is via coastal upwelling, which begins when the adjacent land mass becomes warmer relative to the AS, and low pressure develops over the Arabian Peninsula3,7,8. During this time of the year, strong topographically-steered southwesterly winds blowing over the AS form a low-level atmospheric jet called the Findlater Jet9. This jet induces a northeastwardly flow of the surface currents, leading to strong upwelling of deep, nutrient-rich waters, causing large phytoplankton blooms along the coasts of Somalia, Yemen, and Oman3,5,6,10,11. In contrast, during winter, when the Eurasian continent cools, nutrient enrichment is via deep penetrative convective mixing as a result of excessive heat loss from the AS surface layer caused by cold and dry northeasterly winds blowing from the snow-covered Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau (HTP)4,5. The erosion of the thermocline, and entrainment of deep (100–150 m) nutrient-rich waters into the surface layer of the AS, begins as early as Dec., and has a major influence on winter phytoplankton blooms observable as far south as 14°N4,11,12.

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change on the monsoonal system have elicited a large number of studies in recent years8,13,14. Most of these have focused on the summer monsoon, because of its implications for rainfall patterns and water supply in countries downstream of the summer monsoon13,15–17; and especially because of its consequences for coastal upwelling, biological productivity and fisheries in countries bordering the AS3. In contrast, the response of the boreal winter component of the monsoon cycle to global warming has received far less attention, despite knowledge that it has a significant impact on annual precipitation patterns over the HTP region and over southeast India and Sri Lanka18, and on winter convective mixing, responsible for sustaining the large phytoplankton blooms of winter, which contribute significantly to enhancing the rich fisheries potential of the AS4,5,12,19.

A recent study20, based on results from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5), predicts that the AS will experience significant weakening of winter monsoon winds by the turn of the 21st century due to enhanced warming of the dry Arabian Peninsula relative to the southern Indian Ocean. Weaker winds would result in a substantial reduction in oceanic heat loss to the atmosphere and robust weakening of convective mixing, which the authors20 postulate would lead to a reduction in the productivity and size of winter phytoplankton blooms in the AS.

Here we present data on more contemporaneous changes in winter convective mixing using mixed layer depth (MLD) outputs from the Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS)21, a real time analysis and reanalysis system used for retrospective analysis, and for monitoring of present-day oceanic conditions. Using contemporary Chlorophyll a (Chl a, a proxy for phytoplankton biomass) data obtained from satellite and field studies, we attempt to explain why the response of the AS ecosystem under a scenario of weaker winter convective mixing and enhanced stratification, differs substantially from what has been projected in previous studies20,22.

Results and Discussion

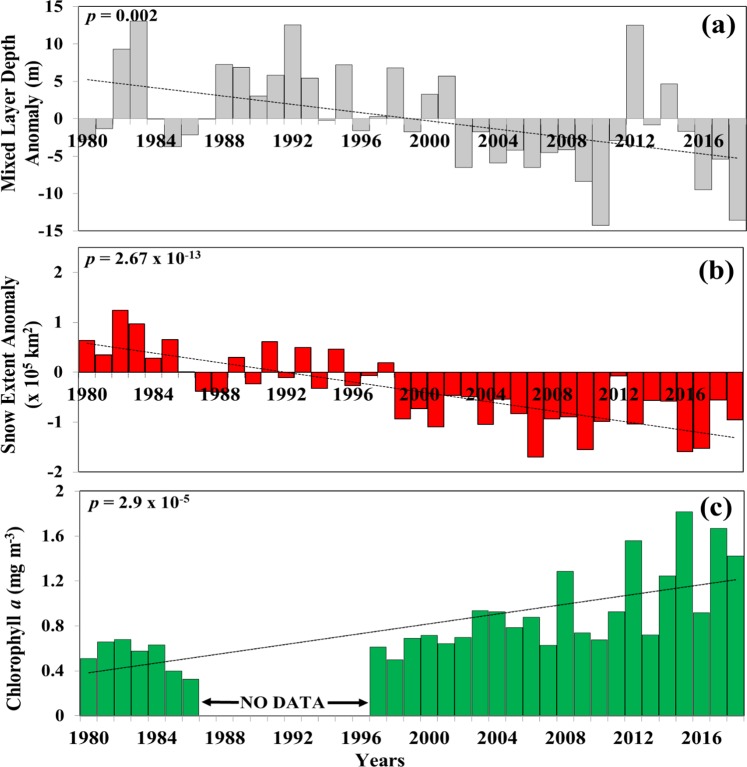

Consistent with CMIP5 projections shown earlier20, MLD trends from GODAS also show a weakening of winter convective mixing (Fig. 1a), but notably at a rate (0.28 m yr−1) much faster than the 0.15 m yr−1 rate predicted in the CMIP5-based study20. Despite certain limitations21,23,24, GODAS provides more realistic and robust outputs of MLDs than CMIP5, because it is a real-time ocean analysis and reanalysis system, in which model outputs are constrained by in-situ observations, unlike the unconstrained ensemble climate projections of CMIP5. Outputs from GODAS show that since 1980, winter-time average AS basin-wide MLDs have decreased by>11 m, a change that has been accompanied by a warming of winter monsoon winds (~0.012 °C yr−1), a decline in the strength of these winds (~0.006 m s−1 yr−1) and an increase in their relative humidity (0.1% yr−1) (Fig. S1a–c). Collectively, these changes have resulted in an increase in net-heat flux from the atmosphere into AS surface waters (Fig. S1d) that indicates an increase in the upper AS ocean heat content (OHC) since 200025. Convective mixing is driven primarily by buoyancy destabilizing forces that include cooling and/or evaporation and that cause surface ocean waters to become colder, saltier and denser than the underlying waters. The process is greatly enhanced when the overlying winds are colder, drier and stronger, but conversely, weakened when they become warmer and more humid as witnessed recently in the AS (Fig. S1a–c).

Figure 1.

Time series of winter-time, AS area-averaged anomalies (departures from means) of: (a) mixed layer depth, (b) HTP snow cover extent, (c) Chl a concentrations (not anomaly). Trends (dashed lines) were obtained using linear least square regression fits to the data. Also shown in Figs are p values associated with individual trends (Additional details in methods section). All the data processing was conducted using the cloud computing technology in the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform (https://earthengine.google.org/)59.

The temperature of winter winds and their dryness is governed in large part by the extent of winter snow cover over the HTP10–12, which also impacts land-ocean temperature and pressure gradients that modulate the strength of the winter monsoonal winds15,16,18–20. Since 1998, the HTP has experienced a persistent year-on-year decline (~5 ×103 yr−1) in snow cover extent26 (Fig. 1b), attributable to the warming of the Eurasian continent (Fig. S2)3, a trend that has possibly been exacerbated by the deposition of soot and dust on the HTP snow surface27. Regression analysis of HTP snow cover extent versus average mixed layer depths indicates that the loss of snow accounts for around 51% of the recent shallowing trends in the mixed layer of the AS (Fig. S3, r2 = 0.51, p < 0.0001), through generation of warmer, weaker and more humid offshore-blowing winds that result in an increase in net heat flux (Fig. S1a–d). Cumulatively the major consequence of these changes is the undermining of convective mixing responsible for nutrient entrainment into the euphotic zone and the fertilization of large winter phytoplankton blooms4.

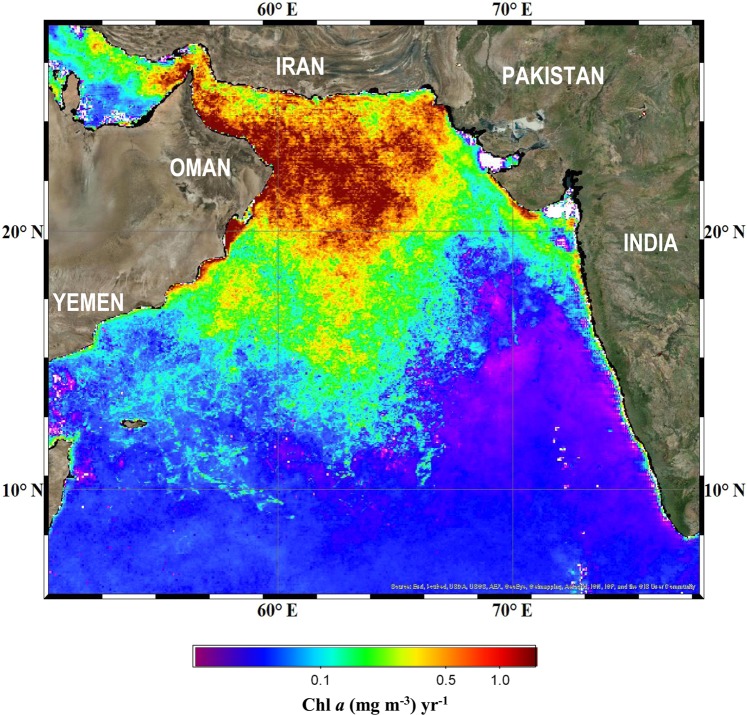

Although a decline in winter biological productivity as forecast previously20,22 under the current scenario of weaker convective mixing and enhanced stratification seems like a realistic conjecture, trends in satellite-derived chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentrations present a different picture (Figs. 1c, 2). Since the early 2000s, winter-time Chl a concentrations averaged for the AS have been on the rise, increasing over 3-fold in recent years, particularly in the northwestern and central AS (Fig. 2), where winter Chl a concentrations now supersede those measured during the more productive summer monsoon season (Fig. S4). What is different, however, is that this increase in winter monsoon Chl a concentrations is not being fuelled by diatoms; the ubiquitous, trophically important, siliceous photosynthetic organisms, which dominated winter phytoplankton communities in the AS during the 1960s International Indian Ocean Expeditions (IIOE) and the mid-1990’s Joint Global Ocean Flux Studies (JGOFS)4,28. Rather, this is due to blooms of the mixotrophic green dinoflagellate Noctiluca scintillans Suriray (synonym Noctiluca scintillans Macartney)29–34. Since they were first detected in the early 2000s29,31,32,35,36 green Noctiluca blooms have become increasingly more pervasive over diatoms (Fig. S5) and more widespread, occurring every winter with predictable regularity33,35–40.

Figure 2.

Spatial distributions of linear trends in winter-time Chl a in the AS for the period between 1996 and 2018. (Additional details in methods section). Data processing was undertaken with GEE59.

So how is a changing AS ecosystem, whose upper water column is becoming increasingly stratified and bordering nutrient limitation, benefiting Noctiluca? Here, we contend that changes in physico-chemical conditions in the euphotic water column caused by stratification, as well as Noctiluca’s mixotrophic mode of nutrition, act in tandem to give this organism a tremendous competitive advantage.

Firstly, as a mixotroph31,35,41, Noctiluca can meet its metabolic requirements via autotrophic CO2 fixation by thousands of free-swimming prasinophyte symbionts: Protoeuglena noctilucae42 within its central vacuole (symbiosome) (Fig. S6), and also via heterotrophic feeding on a wide range of external prey including phytoplankton, micro- and mesozooplankton and zooplankton eggs36,41,43. This mixotrophic mode of feeding gives green Noctiluca a trophic advantage over both autotrophic and heterotrophic plankton and makes it different from the globally ubiqutous red Noctiluca species, which are devoid of endosymbionts and exclusively heterotrophic44.

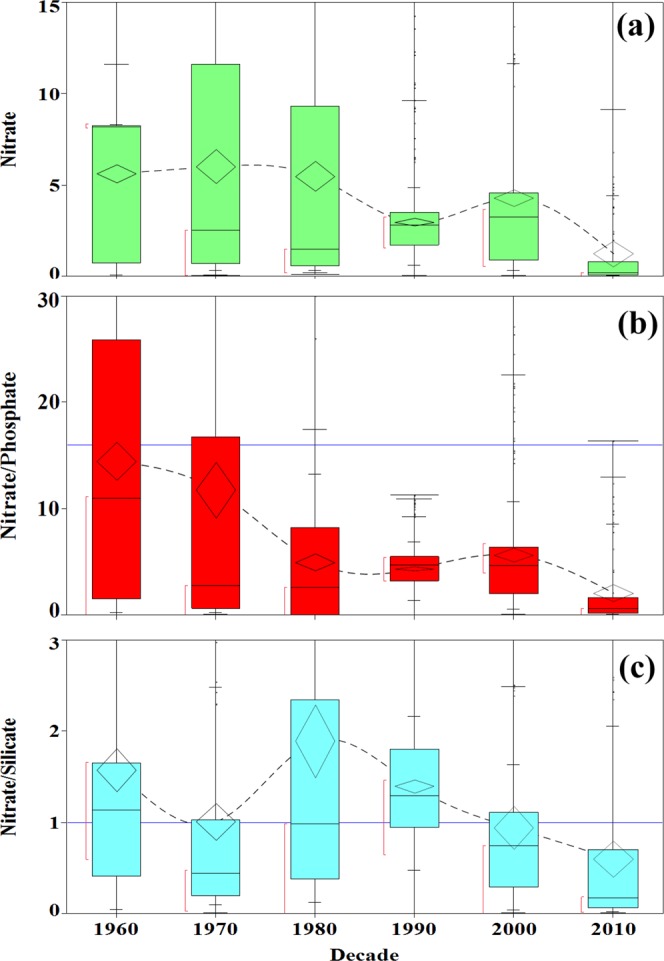

Secondly, our earlier work had ascribed the advent of Noctiluca blooms to the upshoaling of hypoxic waters in the euphotic zone35, caused by a possible expansion of the AS’s permanent oxygen minimum zone (OMZ)45. In this study35, we showed using shipboard experiments in which natural populations were exposed to suboxic seawater36 that endosymbionts in Noctiluca cells photosynthesized more efficiently under suboxic conditions. More recent studies33,34,39, have attributed the advent of Noctiluca blooms to acute “silicate stress”, a situation that would prevent diatom populations from attaining bloom proportions, particularly in the northwestern AS where they have been the predominant algal group in the past28,29,32,46. Our examination of winter-time nutrient concentrations coincident with Noctiluca blooms provides no evidence of silicate stress31, but instead raises the intriguing possibility that autotrophic phytoplankton in the contemporary AS ecosystem may in fact be experiencing acute “nitrate stress”. Analysis of nitrate concentration data, starting with the earliest measurements from the IIOE cruises of the 1960s up to more recent data collected during our Noctiluca bloom study cruises, show that the AS is experiencing a significant loss of nitrate inventories (Fig. 3a) within the upper euphotic column; a trend that in all likelihood, is being fostered by enhanced water column denitrification and ammonification on account of the AS’s expanding permanent OMZ45. Datasets of nutrient measurements from the early 1960s to date provide no evidence of any increases in inorganic phosphate in the AS, as would be expected from enhanced weathering of continental rocks in a warmer and more humid environment47. The decline in euphotic column nitrate concentrations and the profound departure in both NO3:PO4 and NO3:SiO4 ratios from traditional Redfield ratios (Fig. 3b,c) is unparalleled for any open ocean ecosystem. In this nutrient-poor scenario, we contend that as with other mixotrophs48, Noctiluca’s dual mode of obtaining nutrients36, confers upon it a significant competitive advantage over autotrophic phytoplankton especially when nutrients are limiting. When feeding on external prey, Noctiluca accumulates large amounts of nitrogen as ammonium (0.003–0.012 μM NH4+ cell−1) within its central cytoplasm36, alleviating its dependence on extraneous NO3. Feeding on external phytoplankton prey also reduces the standing stock of autotrophs competing for seawater nutrients, providing an additional advantage for Noctiluca. Additionally, in laboratory cultures illuminated on a diel cycle, we have consistently observed that Noctiluca grows best in medium enriched with ammonium. Laboratory-grown Noctiluca can also survive in the absence of nutrients and external prey for prolonged periods of time (~1 year), suggesting an internal, tight nutrient recycling mechanism that ensures its survival under conditions that would be considered hostile for most autotrophic phytoplankton.

Figure 3.

Decadal changes in (a) Nitrate, (b) Nitrate:Phosphate and (c) Nitrate:Silicate ratios in the AS. Blue horizontal lines in panels (b,c) represent typical seawater ratios (Redfield ratios) of 16:1 for NO3:PO4 and 1:1 NO3:SiO3, respectively. The ends of each box represent the 25th and 75th quantiles, respectively. The confidence diamonds contain the mean and the upper and lower 95% of the mean. The brackets to the left of each box identify the shortest half, which represent the densest 50% of the observations (Additional details in methods section).

Thirdly, Noctiluca’s ecological success and range expansion in the AS also appear to be tied to the lack of predatory pressure35. Noctiluca’s only known consumers are salps (Fig. S7) and jellyfish, which appear off the Omani coast in January, and in the central AS by March, long after large blooms of Noctiluca are established.

Finally, dinoflagellates, the functional group that Noctiluca belongs to, prefer less turbulent waters49 and typically reach their greatest abundance at the surface during relatively quiescent and nutrient-deplete periods50. This stands in contrast to diatoms, which with a few exceptions47 are generally restricted to more turbulent and nutrient-rich conditions50,51. In field studies, we have consistently noticed that a highly stratified and stable water column is favorable to the formation of Noctiluca blooms. This is evident along the coast of Oman, where although coastal upwelling shoals Noctiluca-favorable hypoxic waters into the upper euphotic zone as early as Aug. (Fig. S8), accumulation of Noctiluca to bloom proportions takes place only in sheltered coastal, embayments, when the summer monsoon winds ease29 and the water column becomes more stable than offshore waters. Offshore in the AS, prior to their appearance as surface blooms in Dec-Jan, Noctiluca are found at depth31, often close to the oxycline and where photosynthetically available radiation (PAR) is <100 μmol (photons) m−2 s−131. Surface Noctiluca blooms appear by early Jan.31, when the water column begins to stratify, under high light conditions that are typical at that time of the year. Then in the presence of extraneous prey, they transition to a greater dependence on heterotrophy to attain the high growth rates of ~1.2 cells day−1 35,36 necessary for bloom formation.

Besides the build-up of ammonium31,36 mentioned earlier, Noctiluca can accumulate significant amounts of lipids in its central cytoplasm when feeding on extraneous prey31, which makes individual cells increasingly buoyant and thus easily prone to dispersal by surface currents, filaments and streamers associated with mesoscale eddies52, allowing it to become more widespread (Fig. 2).

In summary, we contend that while Noctiluca outbreaks are triggered each summer by the intrusion of hypoxic waters into the upper layers of the euphotic column35, conditions under which Noctiluca’s endosymbionts have shown to have higher rates of photosynthesis than free-living autotrophs. Stratification and a stable water column aid in enhancing their growth to large bloom proportions. In the latter situation, Noctiluca’s unique mixotrophic mode of obtaining nutrition offers it considerable advantages over autotrophs, which are severely nutrient limited by a weaker convective mixing due to the loss of snow cover in the HTP, and changes in nutrient stoichiometries caused by the expansion of the OMZ. Under these conditions, Noctiluca’s unique symbiotic system provides it with a tight nutrient recycling mechanism; wherein nitrogenous nutrients, accumulated during digestion of ingested prey, help alleviate nutrient limitation in the external environment.

A recent study53 has drawn attention to an increase in anthropogenic organic carbon exiting the northern Arabian (Persian) Gulf that may be contributing significantly to the expansion of the OMZ in the northwestern AS, where Noctiluca blooms have been particularly more intense (Fig. 2).

Recent observations of Noctiluca blooms, in association with the shallowing of hypoxic waters along the coast of Oman during the summer upwelling season30, have raised the specter that this organism may also be expanding its temporal range to include the highly productive summer period when diatom blooms support Oman’s large coastal artisanal fisheries. In under-developed countries like Somalia and Yemen, which are currently being challenged by unrest, poverty and deprivation54,55, and where fisheries are the primary source of protein and income, any further loss of fishery resources, due to the spread of hypoxia (Fig. S8), has the potential to further exacerbate socio-economic turmoil in the region, including piracy on international shipping56.

The inability of large zooplankton, except salps and jellyfish to feed on Noctiluca, is indicative of the capacity of Noctiluca blooms to short-circuit the trophic food chain. Thus, their annual reoccurrence and growing dominance in winter each year will require a revision of our fundamental understanding of the AS food web garnered from the AS-JGOFS era6, when autotrophs dominated during productive seasons and alternated with diazotrophs during the transition to nutrient limiting conditions of the inter-monsoon seasons28. The emergence of a mixotroph as a dominant organism will also necessitate revisions to the traditional manner in which AS carbon cycling and biogeochemical rate processes are modeled and studied. Current models compartmentalize organisms at the base of the food chain into autotrophic phytoplankton and heterotrophic zooplankton, but mixotrophy blurs the strict boundary between producers and consumers48,57,58. Recent model simulations58 that include mixotrophs have indicated that mixotrophy greatly enhances the transfer of biomass to larger size classes further up the food chain, which is consistent with our observations of large amounts of salps, jellyfish, and squid in the AS, particularly along the coast of Oman in association with Noctiluca blooms.

Methods

Mixed layer depth anomalies were calculated using area averaged (60°E–70°E, 14°N–25°N) mixed layer data for the months of Jan-Feb-Mar data from Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) model of NOAA, Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Sciences Division. GODAS is a real-time ocean analysis and a reanalysis system, forced by the momentum flux, heat flux and fresh water flux. It assimilates temperature and synthetic salinity profiles from NCEP Atmospheric Reanalysis 2. Mixed Layer Depth is a product of the K-Profile Parameterization (KPP) Mixed Layer Scheme and is the depth where the buoyancy difference with respect to the surface is equal to 0.03 cm s−2. The data are available at 1/3o × 1/3o. The period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1980 to 2018.

Air temperature anomalies over the AS were calculated using the area averaged (50°E–77.5°E, 8°N–25.6°N) air temperature data from the NOAA, National Centers for Environmental Prediction, Department of Energy (NCEP/DOE) Reanalysis-2 project. The data used are for the months of Jan-Feb-Mar, and available from the NOAA, National Centers for Environmental Information. The data period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1949 to 2018, and the plot is from 1970 to 2018.

Wind speed anomalies over the AS were calculated using the area averaged (50°E–77.5°E, 8°N–25.6°N) wind speed data for the months of Jan-Feb-Mar, obtained from NOAA, Climate Data Record, Ocean Near-Surface Atmospheric Properties, Version 2. The data period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1988 to 2017.

Relative humidity (RH) anomalies over the AS were calculated using area averaged (50°E–78°E, 8°N–25.6°N) RH data for the months of Dec-Jan-Feb, obtained from NASA MERRA 3D IAU State, Meteorology Monthly Mean V5.2.0. The data period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1980 to 2016.

Net Heat Flux anomalies over the AS were calculated using the area averaged (50°E–77.5°E, 8°N–25.6°N) net heat flux data for the months of Jan-Feb-Mar, from NOAA, NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis 2. The data period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1960 to 2017.

Eurasian snow cover extent anomalies were calculated using area averaged (60E°–80°E, 20°N–40°N) snow cover extent data obtained from NASA, National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC), Northern Hemisphere EASE-Grid 2.0 Weekly Snow Cover and Sea Ice Extent, Version 4. The data period used for calculating the anomalies is from 1967 to 2018.

Trend lines and p values shown in Figs. 1a–c, S1a–d are based on ordinary least square fits to the time series data.

Area averaged (80°E–120°E, 20°N–40°N) air temperature anomalies over Eurasia for the period were obtained using air temperature data from 1948 to 2016 obtained from the Climate Research Unit Temperature (CRUT) Version 4.01, University of East Anglia, UK.

Area averaged (50° to 77.5°E, 8° to 25.6°N) Chl a concentrations as Level 3 products for winter (Jan-Feb-Mar) were obtained from NASA CZCS (Oct.1978 to Jun. 1986, Version 2014.0), Japan National Space Development Agency OCTS (Nov 1996 to Jun. 1997, Version 2014.0), NASA SeaWiFS (Sept 1997 to Dec. 2010, Version 2018.0) and NASA MODIS-Aqua (Jul. 2002 to present, Version 2018.0). For the period between Jul. 2002 and Dec. 2010, when SeaWiFS and MODIS-Aqua overlapped, the data presented are based on the means of the two data sets. All datasets have been processed by the Ocean Biology Processing group at NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre (GSFC). These daily products have been corrected for atmospheric light scattering and for sun angles differing from the nadir. In addition, the influence of clouds has been substantially reduced. To account for sensor degradation over time, the instrument is calibrated using internal lamps, solar diffuser observations, and lunar images, as well as vicarious methods.

Seawater nutrient data for estimating decadal changes in winter time (Dec-Jan-Feb-Mar) NO3:PO4 and NO3:SiO3 ratios (55°E–76°E, 8°N–24°N) in the upper 80 m of the AS were obtained from NOAA, National Centers for Environmental Information, USA, Indian National Oceanographic Data Centre, India, National Science Foundation, Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office, USA, British Oceanographic Data Centre, UK and oceanographic cruises of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Govt. of India. The data period ranged between 1965 and 2011.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Aeronautical and Space Agency (NASA), the Gordon Betty Moore Foundation and the Sultan Qaboos Cultural Centre to JIG and HRG, from NASA to SdR, from Tiangong University and the China Scholarship Council to HT, from Xiamen University and China Scholarship Council to HL. KH is supported by Sultan Qaboos University, LK and AA by the Ministries of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth and Foreign Affairs respectively. The authors would like to thank NASA, Ocean Biology Processing Group, for ocean color data from CZCS, SeaWiFS, MODIS-Aqua, the National Space Development Agency of Japan for data from OCTS, NASA, National Snow and Ice Data Centre, for the Northern Hemisphere EASE-Grid snow cover data, the NOAA, Climate Diagnostics Center for the reanalysis data products, NOAA National Centre for Environmental Prediction, for MLD data, NOAA, National Centers for Environmental Information, Indian National Oceanographic Data Centre and the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Govt. of India, for seawater nutrient data, the Climate Research Unit at University of East Anglia for air temperature data and the University of Washington, and the International ARGO Program for the Argo float data from the coast of Oman and Yemen. We acknowledge the Google Earth Engine for our data processing and data display.

Author contributions

J.I.G., H.R.G. and H.T. conceived this study. H.T. extracted all of the snow, atmospheric and oceanographic data from various databases (cited in the article). J.I.G. separately extracted nutrient data from various databases. O.R.A. contributed to the development of the sections related to mixotrophy and the ecological success of Noctiluca J.I.G., H.R.G., H.T., O.R.A. and S.D.R., contributed to writing of the manuscript. K.H., H.L., L.K., A.A. contributed field observation data and to the discussion of the results presented in the manuscript. D.G.M., conducted statistical tests required to demonstrate the robustness of the trends in the snow cover extent, atmospheric and oceanographic datasets used in the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-64360-2.

References

- 1.Clemens S, Prell W, Murray D, Shimmield G, Weedon G. Forcing mechanisms of the Indian Ocean monsoon. Nature. 1991;353:720–725. doi: 10.1038/353720a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brock JC, McClain CR, Luther ME, Hay WW. The phytoplankton bloom in the northwestern Arabian Sea during the southwest monsoon of 1979. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 1991;96:20623–20642. doi: 10.1029/91JC01711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goes JI, Prasad TG, Gomes H, Fasullo JT. Warming of the Eurasian landmass is making the Arabian Sea more productive. Science. 2005;308:545–547. doi: 10.1126/science.1106610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madhupratap M, et al. Mechanism of the biological response to winter cooling in the northeastern Arabian Sea. Nature. 1996;384:549. doi: 10.1038/384549a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison JM, et al. The oxygen minimum zone in the Arabian Sea during 1995. Deep Sea Research II. 1999;46:1903–1931. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(99)00048-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SL. The Arabian Sea of the 1990s: New biogeochemical understanding. Progress in Oceanography. 2005;65:113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2005.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.deCastro M, Sousa MC, Santos F, Dias JM, Gómez-Gesteira M. How will Somali coastal upwelling evolve under future warming scenarios? Scientific Reports. 2016;6:30137. doi: 10.1038/srep30137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin Q, Wang C. A revival of Indian summer monsoon rainfall since 2002. Nature Climate Change. 2017;7:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findlater J. A major low-level air current near the Indian Ocean during the northern summer. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 1969;95:362–380. doi: 10.1002/qj.49709540409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banse K, English DC. Geographical differences in seasonality of CZCS derived phytoplankton pigment in the Arabian Sea for 1978-1986. Deep-Sea Research II. 2000;47:1623–1677. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(99)00157-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggert JD, Murtugudde RG, McClain CR. Processes controlling interannual variations in wintertime (Northeast Monsoon) primary productivity in the central Arabian Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II. 2002;49:2319–2343. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00039-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiggert JD, Hood RR, Banse K, Kindle JC. Monsoon-driven biogeochemical processes in the Arabian Sea. Progress in Oceanography. 2005;65:176–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2005.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roxy, M. K. et al. Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian Ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient. Nature Communications6, 10.1038/ncomms8423 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Turner AG, Annamalai H. Climate change and the South Asian summer monsoon. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:587. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadgil S, Gadgil S. The Indian Monsoon, GDP and Agriculture. Economic and Political Weekly. 2006;41:4887–4895. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goswami BN, Venugopal V, Sengupta D, Madhusoodanan MS, Xavier PK. Increasing Trend of Extreme Rain Events Over India in a Warming Environment. Science. 2006;314:1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1132027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izumo T, et al. The Role of the Western Arabian Sea Upwelling in Indian Monsoon Rainfall Variability. Journal of Climate. 2008;21:5603–5623. doi: 10.1175/2008jcli2158.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vialard J, et al. Factors controlling January–April rainfall over southern India and Sri Lanka. Climate Dynamics. 2011;37:493–507. doi: 10.1007/s00382-010-0970-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keerthi MG, Lengaigne M, Vialard J, Boyer Montégut C, Muraleedharan PM. Interannual variability of the Tropical Indian Ocean mixed layer depth. Climate Dynamics. 2013;40:743–759. doi: 10.1007/s00382-012-1295-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parvathi V, Suresh I, Lengaigne M, Izumo T, Vialard J. Robust Projected Weakening of Winter Monsoon Winds Over the Arabian Sea Under Climate Change. Geophysical Research Letters. 2017;44:9833–9843. doi: 10.1002/2017GL075098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behringer, D. W. & Xue, Y. Evaluation of the global ocean data assimilation system at NCEP: The Pacific Ocean In Eighth Symposium on Integrated Observing and Assimilation Systems for Atmosphere, Oceans, and Land Surface, AMS 84th Annual Meeting, Washington State Convention and Trade Center, Seattle, Washington, 11-15.

- 22.Roxy MK, et al. A reduction in marine primary productivity driven by rapid warming over the tropical Indian Ocean. Geophysical Research Letters. 2016;43:826–833. doi: 10.1002/2015gl066979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang B, Xue Y, Zhang D, Kumar A, McPhaden MJ. The NCEP GODAS Ocean Analysis of the Tropical Pacific Mixed Layer Heat Budget on Seasonal to Interannual Time Scales. Journal of Climate. 2010;23:4901–4925. doi: 10.1175/2010jcli3373.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey VK, Kurtakoti P. Evaluation of GODAS Using RAMA Mooring Observations from the Indian Ocean. Marine Geodesy. 2014;37:14–31. doi: 10.1080/01490419.2013.859642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Han W, Hu A, Meehl GA, Wang F. Multidecadal Changes of the Upper Indian Ocean Heat Content during 1965–2016. Journal of Climate. 2018;31:7863–7884. doi: 10.1175/jcli-d-18-0116.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brodzik, M. J. & Armstrong, R. Northern Hemisphere EASE-Grid 2.0 Weekly Snow Cover and Sea Ice Extent, Version 4. [Snow Cover Extent]. Colorado USA. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. Boulder (2013).

- 27.Xu B, et al. Black soot and the survival of Tibetan glaciers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:22114–22118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrison DL, et al. Microbial food web structure in the Arabian Sea: a US JGOFS study. Deep Sea Research II. 2000;47:1387–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(99)00148-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Azri A, et al. Seasonality of the bloom-forming heterotrophic dinoflagellate Noctiluca scintillans in the Gulf of Oman in relation to environmental conditions. International Journal of Oceans and Oceanography. 2007;2:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Hashmi KA, et al. Variability of dinoflagellates and diatoms in the surface waters of Muscat, Sea of Oman: comparison between enclosed and open ecosystem. International Journal of Oceans and Oceanography. 2014;8:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goes, J. I. & Gomes, H. An ecosystem in transition: the emergence of mixotrophy in the Arabian Sea In Aquatic Microbial Ecology and Biogeochemistry: A Dual Perspective (eds P. Glibert & T. Kana) 245 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

- 32.Gomes dRH, et al. Blooms of Noctiluca miliaris in the Arabian Sea–An in situ and satellite study. Deep Sea Research Part I. 2008;55:751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lotliker AA, et al. Characterization of oceanic Noctiluca blooms not associated with hypoxia in the Northeastern Arabian Sea. Harmful Algae. 2018;74:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prakash S, Roy R, Lotliker A. Revisiting the Noctiluca scintillans paradox in northern Arabian Sea. Current Science. 2017;113:1429–1434. doi: 10.18520/cs/v113/i07/1429-1434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomes, H. et al. Massive outbreaks of Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the Arabian Sea due to spread of hypoxia. Nature Communications5, 10.1038/ncomms5862 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Gomes, H. et al. Influence of Light Availability and Prey Type on the Growth and Photo-Physiological Rates of the Mixotroph Noctiluca scintillans. Frontiers in Marine Science5, 10.3389/fmars.2018.00374 (2018).

- 37.Chaghtai F, Saifullah SM. On the Occurrence of Green Noctiluca Scintillans Blooms in Coastal Waters of Pakistan, North Arabian Sea. Pakistan Journal of Botany. 2006;38:893–898. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baliarsingh SK, et al. Response of phytoplankton community and size classes to green Noctiluca bloom in the northern Arabian Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2018;129:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarma VVSS, Patil JS, Shankar D, Anil AC. Shallow convective mixing promotes massive Noctiluca scintillans bloom in the northeastern Arabian Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2019;138:428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang C, et al. The key to dinoflagellate (Noctiluca scintillans) blooming and outcompeting diatoms in winter off Pakistan, northern Arabian Sea. Science of The Total Environment. 2019;694:133396. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen PJ, Miranda L, Azanza R. Green Noctiluca scintillans: a dinoflagellate with its own greenhouse. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2004;275:79–87. doi: 10.3354/meps275079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, L., Lin, X., Goes, J. I. & Lin, S. Phylogenetic Analyses of Three Genes of Pedinomonas noctilucae, the Green Endosymbiont of the Marine Dinoflagellate Noctiluca scintillans, Reveal its Affiliation to the Order Marsupiomonadales (Chlorophyta, Pedinophyceae) under the Reinstated Name Protoeuglena noctilucae. Protist167, 205–216, 10.1016/j.protis.2016.02.005 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Furuya K, et al. Persistent whole-bay red tide of Noctiluca scintillans in Manila Bay, Philippines. Coastal Marine Science. 2006;30:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison PJ, et al. Geographical distribution of red and green Noctiluca scintillans. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology. 2011;29:807–831. doi: 10.1007/s00343-011-0000-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lachkar Z, Lévy M, Smith S. Intensification and deepening of the Arabian Sea Oxygen Minimum Zone in response to increase in Indian monsoon wind intensity. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2017;2017:1–34. doi: 10.5194/bg-2017-146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomes, R. H. et al. Unusual Blooms of the Green Noctiluca miliaris (Dinophyceae) in the Arabian Sea during the Winter Monsoon In Indian Ocean: Biogeochemical Processes and Ecological Variability Vol. Geophysical Mongraph 185 AGU Book Series (eds J.D.Wiggert et al.) 347–363 (American Geophysical Union, 2009).

- 47.Lenton TM, Watson AJ. Redfield revisited: 1. Regulation of nitrate, phosphate, and oxygen in the ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2000;14:225–248. doi: 10.1029/1999GB900065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitra A, et al. Defining Planktonic Protist Functional Groups on Mechanisms for Energy and Nutrient Acquisition: Incorporation of Diverse Mixotrophic Strategies. Protist. 2016;167:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Margalef R. Life-forms of phytoplankton as survival alternatives in an unstable environment. Oceanologia Acta. 1978;1:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hinder SL, et al. Changes in marine dinoflagellate and diatom abundance under climate change. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:271–275. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barton AD, Finkel ZV, Ward BA, Johns DG. & Follows, M. J. On the roles of cell size and trophic strategy in North Atlantic diatom and dinoflagellate communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013;58:254–266. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan Y, Jebara T, Abernathey R, Goes J, Gomes H. Robust learning algorithms for capturing oceanic dynamics and transport of Noctiluca blooms using linear dynamical models. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0218183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Said T, Naqvi SWA, Al-Yamani F, Goncharov A, Fernandes L. High total organic carbon in surface waters of the northern Arabian Gulf: Implications for the oxygen minimum zone of the Arabian Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2018;129:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alkire, S. et al. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- 55.Chandy, L. No country left behind: the case for focusing greater attention on the world’s poorest countries. (Brookings Institution, Washington, DC., 2017).

- 56.Sumaila UR, Bawumia M. Fisheries, ecosystem justice and piracy: A case study of Somalia. Fisheries Research. 2014;157:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2014.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stoecker DK, Hansen PJ, Caron DA, Mitra A. Mixotrophy in the marine plankton. Annual Review of Marine Sciences. 2017;9:311–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ward BA, Follows MJ. Marine mixotrophy increases trophic transfer efficiency, mean organism size, and vertical carbon flux. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:2958–2963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517118113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorelick N, et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2017;202:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.