Abstract

Construction of a fast, easy and sensitive neurotransmitters-based sensor could provide a promising way for the diagnosis of neurological diseases, leading to the discovery of more effective treatment methods. The current work is directed to develop for the first time a flexible Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) based neurotransmitters sensor by using the ultrasonic-assisted fabrication of a new set of epoxy resin (EPR) nanocomposites based on graphene nanosheets (GNS) using the casting technique. The perspicuous epoxy resin was reinforced by the variable loading of GNS giving the general formula GNS/EPR1–5. The designed products have been fabricated in situ while the perspicuous epoxy resin was formed. The expected nanocomposites have been fabricated using 3%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% GNS loading was applied for such fabrication process. The chemical, physical and morphological properties of the prepared nanocomposites were investigated by using Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, Thermogravimetric analysis, Differential Thermal gravimetry, and field emission scanning electron microscopy methods. The GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites were decorated with a layer of gold nanoparticles (Au NPs/GNS/EPR) to create surface-enhanced Raman scattering hot points. The wettability of the Au NPs/GNS/EPR was investigated in comparison with the different nanocomposites and the bare epoxy. Au NPs/GNS/EPR was used as a SERS-active surface for detecting different concentrations of dopamine with a limit of detection of 3.3 µM. Our sensor showed the capability to detect low concentrations of dopamine either in a buffer system or in human serum as a real sample.

Keywords: Epoxy resin, Graphene nano-sheets, Dopamine biosensor, Neurotransmitters, Gold nanoparticles/graphene/epoxy, Surface-enhanced Raman scattering

Introduction

Dopamine (DA) is one of the most important catecholamine neurotransmitters that have a vital role in the transmission of nerve impulses. Several physiological processes and illnesses including Parkinsonism, Schizophrenia, and Huntington’s disease [1] are related to the changes in the DA levels. Therefore, observing the concentrations of DA receive great attention. Several electrochemical and optical biosensors have reported for the detection of DA [1–3]. The rigid conventional sensors were disadvantaged because of their rigidity from capturing analytes and their deformation by thinned [4, 5]. On the other hand, flexible sensors could capture target analytes more efficiently and showed higher quality signals. Several flexible electrochemical sensor platforms have reported for either in vitro or in vivo monitoring of different biomarkers and neurotransmitters [6–13]. Recently, some researches focused on the fabrication of flexible SERS for their biological applications, which including in situ detection based on wrapped the flexible sensor on a solid substrate; besides, few studies have reported the uses of flexible sensors for the direct detection of analytes in the liquid phase [14].

Significant interest has been noticed in the past few decades for polymer composite materials which, are related to organic–inorganic hybrid components. This is fundamentally attributed to their expected and unexpected final properties, which merge the basic characteristics of each component in one new fabricated material [15–17]. To understand what is happening in such unification of polymers from variable groups with inorganic nanofillers we have to believe the appearance of synergistic effects, which drive the researchers to produce innovative multifunctional new materials [18]. Polymer composite materials are the shape of high-performance products that be produced by an easy method. The broad zone of polymer composite materials applications and its considerable behavior have been implicated considerable awareness in the past few decades. Polymer composite materials have been also frequently distinguished and display fundamental properties due to its low coast and numerous ameliorations in its complete performance [19–25]. They should also expand other demands, for example, better mechanical performance, high operating temperature range, electrostatic discharge, and sufficient chemical resistance through others [26]. Furthermore, graphene nanosheets (GNS), carbon nanotubes, and other carbon-based nanomaterials are widely utilized with a variety of polymers in different forms due to its enormous properties in different fields of application. Amazing exceptional properties that will create new materials with excellent properties such as high specific surface areas, unique size distributions. Such properties permit graphene and/or CNTs to be used in different industrial fields of applications such as sensing, catalysts, solar cells, composites, medical applications, photonics, and fuel cells. Moreover, GNS has electrical conductivity properties sufficient to change completely the conducting behaviors of any materials [27–35].

Raman spectroscopy technique represents a nondestructive analytical technique that has high selectivity, quick response in addition to its ability to provide rich information about the target species without needing sample preparation. The weak Raman intensity has restricted its applications for detecting trace species. Several techniques were applied to enhance the Raman signals; among these techniques, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is the most common one [36]. Uses of the SERS technique enable the detection of many important targets at very low concentration levels with high selectivity and sensitivity in the presence of metal nanoparticles [37]. Several noble metals including silver (Ag), gold (Au) or copper (Cu) nanostructures or their composites with different sizes and shapes have been used as high active-SERS agents [38–42]. The chemical nature, size, shape, and spacing of the metal nanomaterials have the main influences on the intensity of the SERS signals. Ag nanostructured showed the highest SERS signals, but the low stability of Ag nanostructures hindering its SERS applications. Although there is notable progress in SERS research, many challenges achieving a repeatable and quantitative SERS signal and fabrication of uniform and stable nanoparticles hindering its development. Using of colloidal solutions of the noble NPs results in a non-uniform enhancement of the Raman signals due to the accumulations of the NPs. Thus, numerous substrates modified with noble NPs were used as SERS agents. In the current work, we have used the ultrasonic-assisted technique for the fabrication of a new set of epoxy resin (EPR) nanocomposites with different amounts of graphene nanosheets (GNS) including 3%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of GNS using the casting technique. The perspicuous epoxy resin was reinforced by the variable loading of GNS giving the general formula GNS/EPR1–5. Then we have used these composites sheets as flexible substrates for developing SERS substrates based on decorated these GNS/EPR1–5 sheets with Au NPs. We investigate the use of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) based sensors for the rapid detection of dopamine neurotransmitters. According to our knowledge, it is the first time to develop a flexible SERS sensor of detecting dopamine neurotransmitters.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Commercially obtained Epikote-1001 × − 75% (2642) epoxy together with crayamid—100% (2580) epoxy hardener was applied as pure epoxy resin; they were also used as obtained without additional purification. Epikote:crayamid (1:1) weight by weight was adjusted as the exact mixing ratio for pure epoxy processing and fabrication. Spectroscopic grade chloroform was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any additional purification. Furthermore, GNS, dopamine and chloroauric acid tetrahydrate (HAuCl4·4H2O) were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were also used as received. Any other chemicals or materials used were also obtained from a known source, besides, were used as received.

Preparation of pure epoxy resin film

A thin film of pure epoxy resin was easily fabricated by ultrasonic assistance as well as casting technique as reported in our previous work [32, 43, 44]. The following steps were applied: In 50 mL beaker, a fixed weight of 1 g of Epikote-1001 was dissolved in 25 mL of chloroform. Besides that, 1 g of crayamid hardener was also dissolved in similar mL of chloroform in another beaker. Both solutions were exposed to ultrasonicator for 10 min before mixing in a closed container. The whole mixture was constantly exposed to ultrasonicator for an additional 10 min while its top is closed. This sonicated mixture was poured carefully into a Petri dish and left overnight at room temperature for solvent evaporation. The pure epoxy thin film was collected easily and dried in the oven at 40 °C.

Fabrication of GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites

A new set of GNS/EPR nanocomposites with a general formula GNS/EPR1–5was simply fabricated using casting technique and ultrasonic assistance as well. The proposed products were fabricated in situ while the perspicuous epoxy resin was introduced. 3%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% loading of GNS was applied for such fabrication process with respect to the total weight of the perspicuous epoxy resin. In a typical procedure, GNS/EPR1–5was fabricated as follows: In three different beakers variable weights of GNS, 1 g of Epikote-1001 and 1 g of crayamid hardener were separately dissolved in 20 mL of chloroform for each. Such solutions were exposed to ultrasonicator for 10 min before mixing in a closed container. The total mixture was continuously exposed to ultrasonicator for an additional 10 min while its top is closed. This sonicated mixture was poured carefully into a Petri dish and left overnight at room temperature for solvent evaporation. A thin film of GNS/EPR1–5 was collected easily each time and dried in the oven at around 40–50 °C. These procedures were repeated five times with a different weight of GNS was introduced each time. The designed compositions for GNS/EPR1–5 formulations were given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Designed compositions and symbols for NEAT EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites

| Sample | EPR (weight, g) | G loading %, (weight, g) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure EPR | (2 g) | – |

| GNS/EPR1 | (1.96) | 3%, (0.06) |

| GNS/EPR2 | (1.90) | 5%, (0.10) |

| GNS/EPR3 | (1.80) | 10%, (0.20) |

| GNS/EPR4 | (1.70) | 15%, (0.30) |

| GNS/EPR5 | (1.60) | 20%, (0.40) |

Fabrication of Au NPs/GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites modified sheet as a dopamine-based biosensor

Au NPs/GNS/EPR sheet was prepared based on a chemical reduction method in which the GNS/EPR sheets were immersed solution of 1 mM of HAuCl4 and then added few drops of 0.1 M of cooled NaBH4 as a reducing agent. Then rinse the substrate with DIW and dried. To develop the dopamine sensor, fifty microliters of the dopamine solution into the modified substrate and kept for 6 h at 4 °C and then reins the substrate with DIW.

Characterization and identification techniques

Powder X-ray diffractograms were determined in the 2θ range from 5 to 80° with the aid of Philips diffractometer (type PW 103/00) using the Ni-filtered CuKα radiation. FT-IR spectra were examined by using ATR smart part technique within the wavenumber range from 4000 to 400 cm−1 using the Thermo-Nicolet-6700 FT-IR spectrophotometer. Thermal analysis, the TGA curve was recorded with a TA instrument apparatus model TGA-Q500 using a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under nitrogen atmosphere over the temperature range of 21–700 °C. The average masses of the samples were 5–10 mg. The morphological features were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-7600F, Japan). The FE-SEM samples were prepared by evaporating a dilute solution of each nanocomposite on a smooth surface of the aluminum foil, and subsequently coating it with gold–palladium alloy. The microscope was operated at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV and a 4 mm work distance carbon film.

The chemical composition of the prepared resins and their different composites, as well as the SERS efficiency of the Au NPs/GNS/EPR1–5, were studied by Raman spectroscopy using a Bruker Senterra Raman microscope (Bruker Optics Inc., Germany) with 785 nm excitation, 1200 rulings mm-1 holographic grating, and a charge-coupled device (CCD) detector. The accumulation time was 3 s with a power of 50 mW. Five scans of 5 s from 200 to 2000 cm−1 were measured and the mean of these scans was used.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterizations of different GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites sheets

Variable characterization techniques are utilized to recognize the chemical structure and to confirm the formation of these expected products.

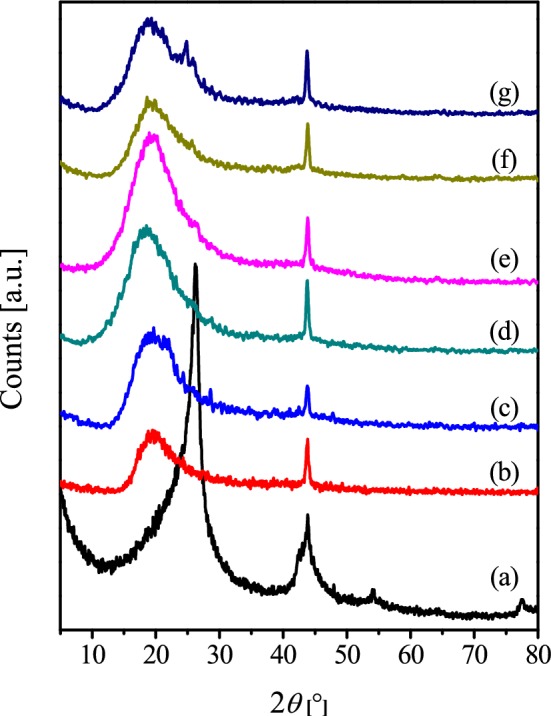

To investigate the structures of the prepared GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites and the dispersion of GNS in their matrix, XRD analysis has been performed. Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns for GNS, neat epoxy and their prepared nanocomposites with various GNS contents. The diffractogram of the as-received neat GNS (Fig. 1a) shows four broad-diffraction peaks at 2θ = 26.20°, 43.80°, 54.33°, and 77.45°, which correspond to the interlayer spacing of 0.3398, 0.2065 and 0.1687 nm. These reflections match well with those reported for GNS [45, 46]. The diffractogram of neat EPR (Fig. 1b) shows a broad reflection at 2θ = 13–32° and a sharp one at 2θ = 43.85°. The obtained diffractograms for the composites with GNS content of 3 and 5 wt% resemble very closely to the XRD pattern of the neat epoxy (Fig. 1c, d). In this context, Zaman et al., [47] demonstrated that epoxy-graphene composites contain low graphene loading (~ 0.5 wt%) exhibit sharp XRD peak at 26.5° attributable to layered crystalline GnPs, which indicates the persistence of the graphene-layered structure. Epoxy/reduced graphene oxide (RGO) and ternary epoxy/RGO/powdered rubber (PR) composites showed the absence of such diffraction peak and the presence of wide one at 2θ = 5°–28°, due to the scattering of the cured epoxy molecules, which indicates amorphous nature of these composites [48]. Two points could be highlighted from the absence of GNS diffraction peaks for our nanocomposites with loading 3–5%: (i) the reflections of G for the low GNS-content composites could be masked by the resin signal, and (ii) this indicates the homogeneous intercalation of epoxy chains into the GNS interlayer together with the exfoliation of the graphene sheets in the epoxy matrix. A similar argument was proposed by Wan et al. [49, 50] for their epoxy composites filled with graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (RGO) and diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A functionalized GO (DGEBA–f–GO).

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of GNS (a), neat EPR (b), GNS/EPR1 (c), GNS/EPR2 (d), GNS/EPR3 (e), GNS/EPR4 (f) and GNS/EPR5 (g)

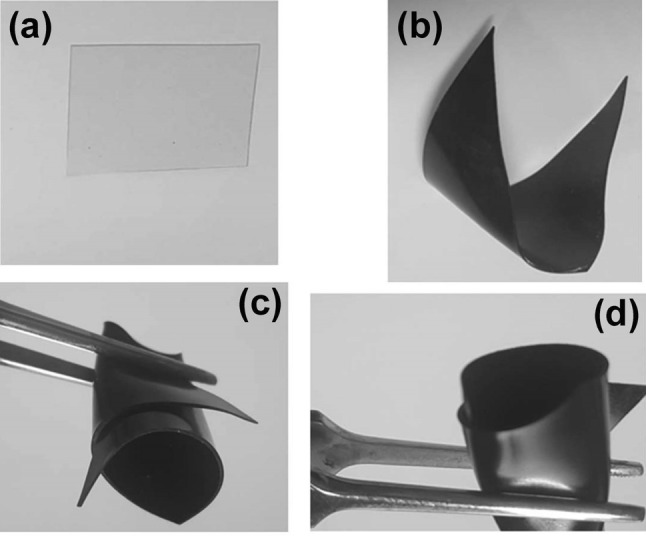

Increasing the GNS-content to GNS/EPR3 is accompanied by an emergence of small reflection at 2θ = 26.57°, attributable to the main XRD-peak for GNS (Fig. 1e). Further increase in the GNS wt% till 20% leads to a continuous shift of that reflection to 2θ = 24.81° (Fig. 1g), which indicates a larger interlayer spacing (0.3574 nm) than that of the bare GNS; meanwhile, the patterns for the various composites still showing the features characterizing the EPR. The detection of these peaks indicates that the structure of neither graphene nor the epoxy resins was not destroyed during the composite-preparation process. Concurrently, Yu et al. [51] reported a shift in the XRD main peak of GO from 10.0° to 9.6° upon anchoring Al2O3 on GO sheets. They have correlated this shift to the formation of the disordered and loosened sheet-like structure of GO [51]. Figure 2 showed the photography images of neat EPR and GNS/EPR1–5, which indicated that we have successfully fabricated flexible sheets with a very simple method that allowed different applications for these nanocomposites sheets with different amounts of GNS.

Fig. 2.

The photography images of neat EPR (a) and GNS/EPR1–5 (b–d)

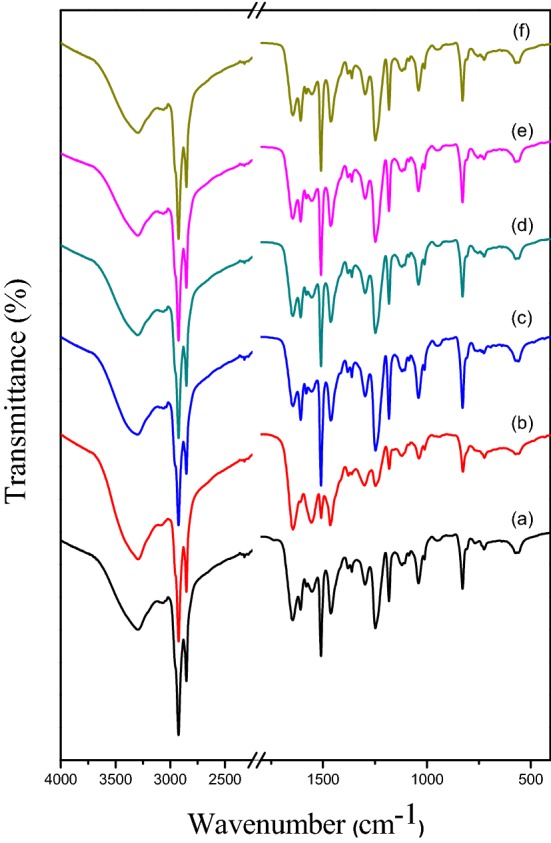

FT-IR spectra for the neat EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5graphene-containing nanocomposites are measured using ATR smart pat over the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1. A visible proof for the expected bonding interaction between neat EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites is given in Fig. 3. The neat EPR spectrum shows all characteristic absorption peaks as reported in our previous work [32, 43, 44] and as reported in the open literature [52, 53]. Peaks at 3050–3015 cm−1, 3045 cm−1, and 2965 cm−1 are attributed to the valent CH vibrations of the epoxy ring, the stretching CH vibration of the aromatic ring, and the stretching vibration of the –CH2 functional group respectively. Furthermore, other peaks at 1245 cm−1 and in the range 930–815 cm−1 for the valent CO vibrations of the epoxy ring, and the bending CH vibrations of the epoxy ring respectively. Moreover, Fig. 3 also asserts such type of interaction where it shows the significant characteristic peaks of GNS in the spectra of GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites [54–57]. Besides that, EPR characteristic peaks are also mentioned in the spectra of these products. FT-IR spectra of GNS/EPR1–5 in Fig. 3 also display that, a major decrease in the intensity of neat EPR characteristic peaks is obviously observed and vice versa for GNS immersed fillers.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR spectra of neat EPR (a), GNS/EPR1 (b), GNS/EPR2 (c), GNS/EPR3 (d), GNS/EPR4 (e) and GNS/EPR5 (f)

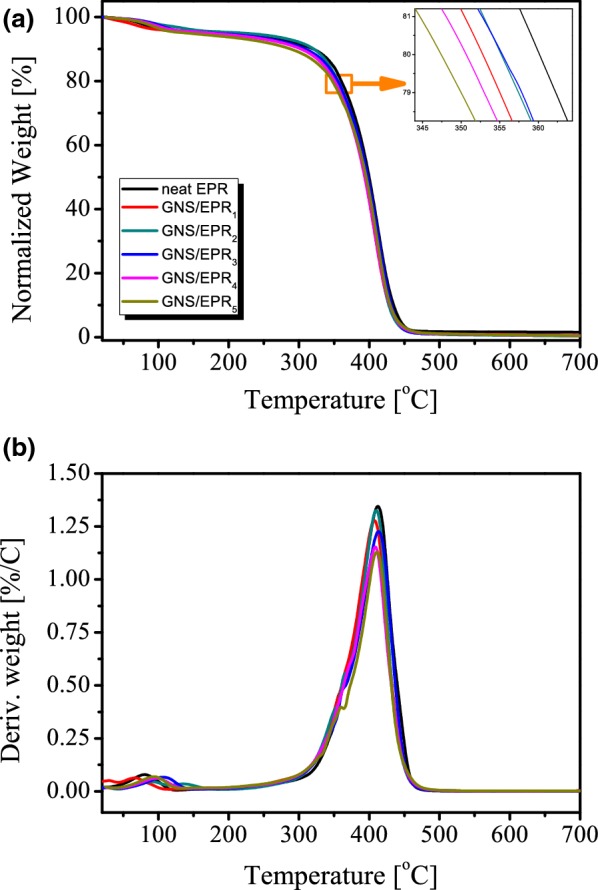

TGA was used to investigate the thermal stability of the neat EPR and its various GNS/EPR1–5nanocomposites over the temperature range of 21–700 °C. Figure 4a shows plots of the normalized weight loss (NWL) percentages versus temperature. The NWL is defined as [(wT/wG)/(winit/wG)] × 100, where wT is the weight at temperature T, wG is the graphene weight, and winit is the sample initial weight. All the obtained thermograms show two weight loss steps. The first one extends from ambient to 180 °C and amounts to 4.5–5.8%, which could be attributed to the evolution of impurity traces apart from the cured epoxy resin together with the elimination of water molecules [43, 44]. The second weight-loss step, which is the main step that is characterized by a steep weight change, takes place at the temperature range of 250–500 °C. This step could be assigned to the chain scission together with resin decomposition yielding lower molecular weight products [43, 44]. The obtained TGA curves of the fabricated GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites are very similar to that of neat EPR. Table 2 lists the T2, T20 (temperatures corresponds to 2%, 20%, and weight loss, respectively) values of neat EPR and its graphene-based nanocomposites. Inspection of these values reveals that the presence of GNS content higher than 3% retards the early weight loss step of the neat epoxy. On the other hand, the T20 values show a 5–13 °C shift toward lower values because of GNS incorporation.

Fig. 4.

TGA (a) and DTG (b) thermoanalytical curves of neat EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites

Table 2.

Thermoanalytical data of neat EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites under nitrogen flow

| Sample | T2 [°C] | T20 [°C] | Tmax [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|

| neat EPR | 74 | 360 | 412 |

| GNS/EPR1 | 60 | 353 | 407 |

| GNS/EPR2 | 95 | 355 | 410 |

| GNS/EPR3 | 93 | 355 | 409 |

| GNS/EPR4 | 87 | 350 | 409 |

| GNS/EPR5 | 81 | 347 | 410 |

Inconsistent thermal-stability trends have been reported in the literature for the incorporation of epoxy with graphene-based materials [46, 48, 49, 58–60]. For instance, Wang et al. [58] reported that, in comparison with the neat epoxy, the SnO2–graphene/epoxy and Co3O4–graphene/epoxy composites exhibited a 37 and 27 °C increment in the onset decomposition temperature, respectively. This increased thermal stability was ascribed to the presence of a metal oxide-G synergic effect. Liu et al. [46] investigated the thermal degradation behavior of the epoxy composites with slightly oxidized graphene (graphenit-ox) and Cu-doped graphene (graphenit-Cu). Their results revealed that the incorporation of graphenit-ox (1–3 wt%) into epoxy resin led to slight thermal stability enhancement. On the other hand, the graphenit-Cu exhibits a catalytic effect, i.e., it decreases the epoxy decomposition temperature. Wan et al. [49] showed that the GO/epoxy composites formation increases the decomposition temperature (Td) of epoxy resin by 12–16 °C. Moreover, the GO loading (0.1–0.5 wt%) did not appreciably affect that temperature [49]. On the other hand, an increase in the Td value by around 30 °C was obtained on functionalizing the GO/epoxy composites with diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A [49]. The recent work of Gong et al. [48] indicated that, in comparison with neat epoxy, the decomposition temperature of epoxy/RGO (0.5 wt% loading) is slightly increased by 12 °C. Replacing RGO with powdered rubber in a 3% and 6% loading led to ~ 54 °C and ~ 104 °C decrease in the decomposition temperature [48]. An and Jeong [59] reported a slight decrease in the decomposition temperature of G/epoxy composites (0.3-7 wt% loading) compared to the bare epoxy resin. Zhang et al. [60] reported a ~ 1 °C increase of the onset decomposition temperature (Tonset) of G/epoxy composite (loading 1.0 wt%) compared to the bare epoxy. Further increase in the G loading to 5 wt% in the form GNS/EPR2 led to a ~ 5.5 °C decrease in the Tonset value [60]. Moreover, the incorporation of Fe@Fe2O3 to the G/epoxy composites in loadings of 1, 3 and wt% was accompanied by 13, 21 and 19 °C decrease in the Tonset value [60]. Table 2 also lists the Tmax (maximum decomposition temperature) values of neat EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites [32, 61–63]. Tmax values were calculated from the DTG thermoanalytical curves (see Fig. 4b). Tmax values are nearly similar for EPR and its GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites which ranged from 407 to 412 °C. This is due to the similar decomposition pattern for all materials (two main degradation steps) as previously discussed. The pure EPR shows somewhat the highest Tmax value while GNS/EPR1 nanocomposite shows the lowest value. In conclusion, our results clearly indicate that the presence of GNS slightly decreases the thermal stability of neat EPR. Moreover, a dependence of the T20 value on the GNS content in the composite form is evident. The T20 decreases on increasing the GNS to 5–10 wt%; higher content leads to a slight increase in the T20 value.

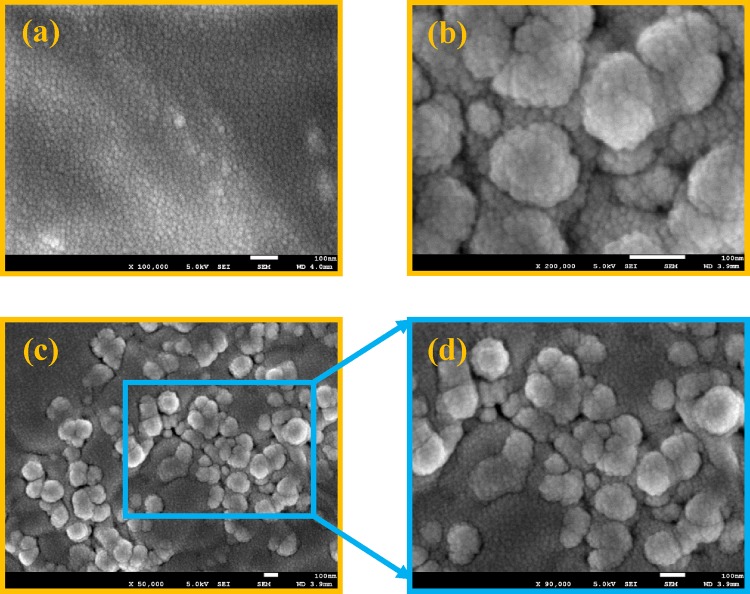

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) is applied to study the morphological surface changes in the fabricated GNS/EPR1–5 graphene-containing nanocomposites. The FE-SEM images show a visible morphological directory for the formation of our designed materials. Fe-SEM micrographs are picked up using a Penta Z Z-50P Camera with Ilford film at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV and a nearly 4 mm work distance carbon film using a low dose technique [64]. The FE-SEM micrographs are illustrated in Fig. 5a–d for GNS/EPR2and GNS/EPR5as the second lowest and the highest loading of GNS. It is clearly noticed from the images that, the neat EPR surface shows a smooth surface under higher magnification x = 100,000; while in very high magnification (x = 200,000), the surface shows tiny spherical particles. Whereas, the dispersion states of the GNS in the neat EPR are easily demonstrated in the FE-SEM images of GNS/EPR2 and GNS/EPR5 as illustrated in Fig. 5a, b. Such FE-SEM micrographs display a valuable surface modification upon GNS inundation inside the EPR polymer matrix. Figure 5 also shows GNS is uniformly dispersed throughout the EPR polymer matrix in the given magnifications. This exposes excellent miscibility between EPR (organic) and GNS (inorganic) parts in the nanocomposites production. A greater sense of compatibility, distribution pattern of the GNS is also specified by these micrographs. Meanwhile, good cohesion between this filler particle and the polymer matrix is also observed. Whoever, the images also show slightly aggregated particles that are attributed to the relatively higher loading of GNS that are found in the composition of GNS/EPR5 as given in Fig. 5c, d.

Fig. 5.

FE-SEM images for GNS/EPR2a x = 100,000, b x = 200,000 and for GNS/EPR5, c x = 50,000, d x = 90,000

Characterizations of different Au NPs/GNS/EPR nanocomposites sheets

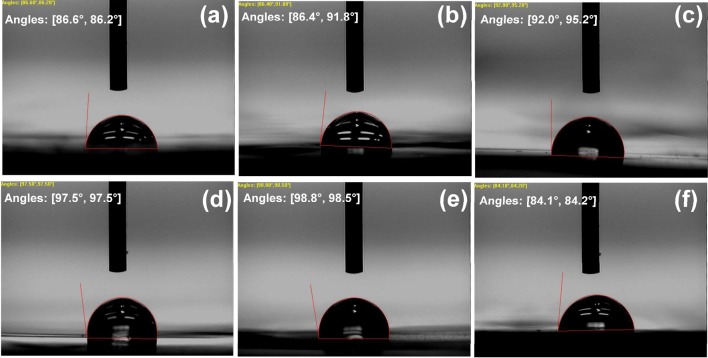

The wettability of developed sensor is one of the important futures in order to allow the immunization of the target species; thus the effect of the amount of the loading GNS on the contact angle between water and the GNS/EPR in addition to the contact angle of Au NPs/GNS/EPR were studied. Figure 6 showed the images of the water contact angles with the different modified GNS/EPR substrate in comparison with the bare resin substrate. The values of the contact angles were summarized in Table 3, which indicated that the contact angle value was increased with increasing the amount of loading of GNS and hence the hydrophobic characteristic will increase that restricted the immobilization of the target species from the aqueous medium. On the other hand, the deposition of Au NPs results in decreasing the contact angle in comparing with the all GNS/EPR1–5 substrates as well as the bare resin substrate.

Fig. 6.

Images contact angles of water with neat EPR (a), GNS/EPR1 (b), GNS/EPR2 (c), GNS/EPR4 (d), GNS/EPR5 (e) and Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 (f)

Table 3.

The contact angle data of neat EPR, GNS/EPR1–5 nanocomposites and its Au NPs/GNS/EPR with water

| Sample | Right contact angle (°) | Left contact angle (°) | Average contact angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure EPR | 86.6 | 86.2 | 86.4 |

| GNS/EPR1 | 86.4 | 91.8 | 89.1 |

| GNS/EPR3 | 92.0 | 95.2 | 93.6 |

| GNS/EPR4 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.5 |

| GNS/EPR5 | 98.8 | 98.5 | 98.65 |

| Au NPs/GNS/EPR | 84.1 | 84.2 | 84.15 |

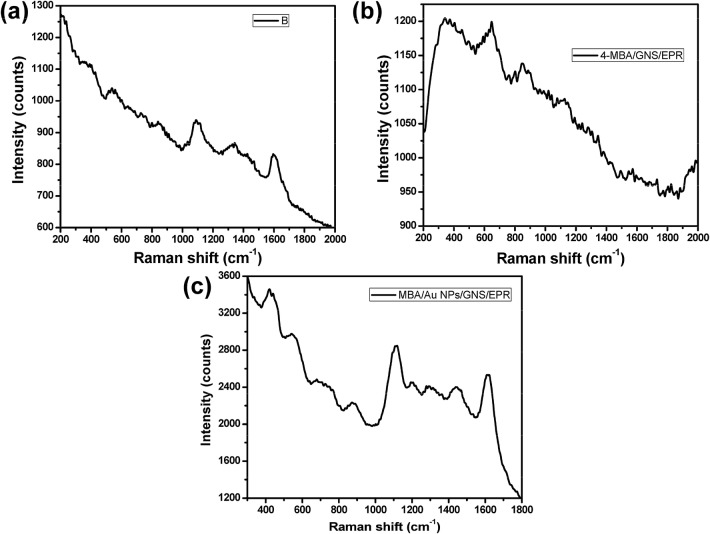

The enhancement factor of the different modified sheets

In order to calculate the enhancement factor (EF), a solution of 2 mM of 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA) in ethanol was immobilized onto the different modified substrates (pure resin, GNS/EPR5 and Au NPs/GNS/EPR1–5) and then the Raman spectra were recorded by using the same laser power and accumulations time. The EF was calculated based on the following equation EF = (SERS intensity x effective SERS analytes)/(Raman intensity x effective Raman analytes). Figure 7a showed the Raman spectrum of 2 mM of 4-MBA immobilized onto the pure resin, which showed a very poor Raman signal. While the GERS spectrum of 2 mM of 4-MBA immobilized on GNS/EPR5 substrate showed a little enhancement of the Raman signals (Fig. 7b). On the other hand, immobilization of 2 mM of 4-MBA onto Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 modified substrate showed the highest enhancement that related to the presence of Au NPs (Fig. 7c), which serves as hotspots for improving the intensity of the Raman signal and also as nanoplatforms for immobilization of 4-MBA based on the direct interaction with thiol groups. The corresponding EF was found to be 6.2 × 106.

Fig. 7.

Raman spectra of 2 mM of 4-MBA with neat EPR (a), GNS/EPR5 (b), and Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 (c)

Monitoring of different concentrations of dopamine neurotransmitter

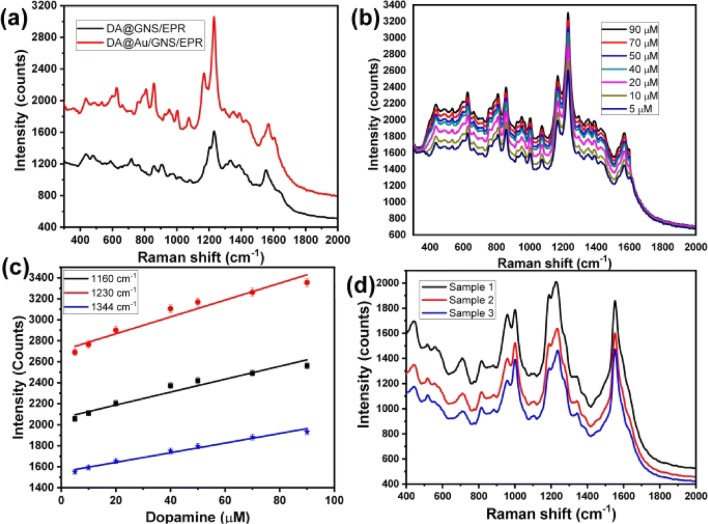

The Raman spectrum of Au NPs/GNS/EPR (Fig. 7c) was as recorded a blank spectrum and subtract before measure the Raman spectra of dopamine. Fifty microliters of dopamine solutions with different concentrations were self-assembled on GNS/EPR as well as Au NPs/GNS/EPR and then the SERS spectra were recorded five times and the average data were represented in Fig. 8a, displayed several Raman bands as following 597 cm−1 (in-plane ring deformation), 627 cm−1 (CH wagging; aliphatic chain C–C vibrations), shoulder Raman band 757 cm−1, 805 cm−1 (CH out-of-plane; ring deformation), 927 cm−1 (NH twisting), 1160 cm−1 (OH rocking; CH aromatic rocking; weak ring breathing; CH wagging), 1230 cm−1 (CO stretching), 1430 cm−1 (CH scissoring) and 1620 cm−1 (NH2 scissoring), which are in good concordant with the previous reported spectra data [40]. Furthermore, it was easily note that the uses of Au NPs/GNS/EPR as SERS-active substrate results in highly enhancement compared with the GNS/EPR. Figure 8b displays the SERS spectra of different concentrations of dopamine that illustrated an increase in the Raman intensities with increasing the dopamine concentration. Figure 8c represented the relationship between the concentration of dopamine within a range from 5 µM to 90 µM and the intensity of the GSERS signals at 1160, 1230 and 1344 cm−1, which displayed a linear relationship with an R2 of about 0.954, 0.951 and 0.983, respectively. Thus the intensity of peak 1344 cm−1 showed the highest successive changes depending on the change in dopamine concentration. The limit of detection (LOD) of the dopamine was calculated as following, (LOD = 3.3*(STEYX/Slope of calibration curve)), and it was found equal to 3.3 µM.

Fig. 8.

Raman spectra of dopamine solution in PBS buffer by using GNS/EPR5 and Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 (a), G-SERS spectra of different concentrations of dopamine dissolved in PBS buffer by using Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 (b), the relationship between the intensities of SERS signals (857, 1074 and 1344 cm−1) and the corresponding concentration of dopamine (c), and G-SERS spectra of different concentrations of dopamine dissolved in human serum by using Au NPs/GNS/EPR5 (d)

Monitoring of dopamine in human serum sample as a model of real samples

The capability to use this sensor to detect dopamine neurotransmitters in a real sample was studied based on monitoring low concentrations of dopamine in human serum as a represented real sample. Figure 8d showed the Raman spectra of three different concentrations of dopamine soluble in human serum solution. The Raman spectra displayed a set of Raman bands similar to the Raman spectrum of dopamine dissolved in PBS buffer with a little difference in the strength of some bands, which established the capability of the Au NPs/GNS/EPR to apply for monitoring dopamine in complicated media such as human serum sample without any interference-effect.

Conclusions

Here we have successfully prepared fillable sheets congaing different amounts of GNS based one-step process in which the epoxy resin (EPR) was fabricated by ultrasonic-assisted and the graphene nanosheets were added while the epoxy resin was formed. The obtained GNS/EPR sheet was decorated with Au NPs to enhance the Raman sensitivity and to allow the immobilization of the target species. This flexible sheet was used for direct monitoring of different concentrations of dopamine neurotransmitters in human serum, thus this flexible sensor can be applied to other biomedical wearable sensor applications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SERS

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

- EPR

Epoxy resin

- GNS

Graphene nanosheets

- GNS/EPR

Graphene nanosheets/epoxy resin

- Au NPs/GNS/EPR

Gold nanoparticles/graphene nanosheets/epoxy resin

- DA

Dopamine

- HAuCl4·4H2O

Chloroauric acid tetrahydrate

- NaBH4

Sodium borohydride

- CCD

Charge-coupled device

- FT-IR

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

- TGA

Thermogravimetric analysis

- RGO

Reduced graphene oxide

- PR

Powdered rubber

- DGEBA-f-GO

Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A functionalized graphene oxide

- Al2O3

Aluminum oxide

- NWL

Normalized weight loss

- Tmax

The maximum decomposition temperature

- Tonset

The onset decomposition temperature

- FE-SEM

Field emission scanning electron microscopy

- EF

Enhancement factor

- 4-MBA

4-mercaptobenzoic acid

- LOD

The limit of detection

Authors’ contributions

MAH and WAE suggest the point, synthesized the materials and measured all the required characterization techniques and participate in writing the manuscript. BMA measures the thermal technique, analyze the results and write the manuscript. J-WC participates in discussing the results, analyzing the Raman data and revised the manuscript finally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under Grant No. (DF-256-130-1441). The authors, therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR for technical and financial support.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mahmoud A. Hussein, Email: maabdo@kau.edu.sa, Email: mahmali@aun.edu.eg, Email: mahussein74@yahoo.com

Waleed A. El-Said, Email: awaleedahmed@yahoo.com, Email: waleed@aun.edu.eg

References

- 1.Shin J-W, Kim K-J, Yoon J, Jo JH, El-Said WA, Choi J-W. Silver nanoparticle modified electrode covered by graphene oxide for the enhanced electrochemical detection of dopamine. Sensors. 2017;17:2771. doi: 10.3390/s17122771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An JH, El-Said WA, Choi J-W. Cell chip based monitoring of toxic effects on dopamingergic cell. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012;12:4115–4118. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2012.5903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Said WA, Lee J-H, Oh B-K, Choi J-W. 3-D nanoporous gold thin film for the simultaneous electrochemical determination of dopamine and ascorbic acid. Electrochem. Commun. 2010;12:1756–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2010.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi S, Lee H, Ghaffari R, Hyeon T, Kim D-H. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:4203. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han S-T, Peng H, Sun Q, Venkatesh S, Chung K-S, Lau SC, Zhou Y, Roy VAL. An overview of the development of flexible sensors. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1700375. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao H, Li AL, Nguyen CM, Peng YB, Chiao JC. An integrated flexible implantable micro-probe for sensing neurotransmitters. IEEE Sens. J. 2012;12:1618–1624. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2011.2173674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windmiller JR, Wang J. Wearable electrochemical sensors and biosensors: a review. Electroanalysis. 2013;25:29–46. doi: 10.1002/elan.201200349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, Xu J, Chen D, Shen G. Flexible electronics based on inorganic nanowires. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:161–192. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00116H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Wu Z, Yuan S, Zhang X-B. Advances and challenges for flexible energy storage and conversion devices and systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014;7:2101–2122. doi: 10.1039/c4ee00318g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aashish A, Sadanandhan NK, Ganesan KP, Hareesh UNS, Muthusamy S, Devaki SJ. Flexible electrochemical transducer platform for neurotransmitters. ACS Omega. 2018;3:3489–3500. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b02055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weltin A, Kieninger J, Enderle B, Gellner A-K, Fritsch B, Urban GA. Polymer-based, flexible glutamate and lactate microsensors for in vivo applications. Biosens. Bioelectr. 2014;61:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castagnola E, Vahidi NW, Nimbalkar S, Rudraraju S, Thielk M, Zucchini E, Cea C, Carli S, Gentner TQ, Ricci D, Fadiga L, Kassegne S. In vivo dopamine detection and single unit recordings using intracortical glassy carbon microelectrode arrays. MRS Adv. 2018;3(29):1629–1634. doi: 10.1557/adv.2018.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan B, Zhu Y, Rechenberg R, Rusinek CA, Becker MF. Large-scale, all polycrystalline diamond structures transferred on flexible Parylene-C films for neurotransmitter sensing, W. Li Lab Chip. 2017;17(18):3159–3167. doi: 10.1039/C7LC00229G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K, Zhou R, Takei K, Hon M. Toward flexible surface-enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Sensors for Point-of-Care diagnostics. Adv. Sci. 2019;6:1900925. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubio E, Almaral J, Ramírez-Bon R, Castano V, Rodriíguez V. Organic-inorganic hybrid coating (poly(methyl methacrylate)/monodisperse silica) Opt. Mater. (Amst.) 2005;27:1266–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2004.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.José NM, Prado LAS. Materiais Hybrid organic-inorganic materials: preparation and some applications. Química Nova. 2005;28:281–288. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422005000200020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KE, Morad N, Teng TT, Poh BT. Development, characterization and the application of hybrid materials in coagulation/flocculation of wastewater: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;203:370–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Torre GC, Espinosa-Medina MA, Martinez-Villafane A, Gonzalez-Rodriguez JG, Castano VM. Study of ceramic and hybrid coatings produced by the sol-gel method for corrosion protection. Open Corros. J. 2009;2:197–203. doi: 10.2174/1876503300902010197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zare Y. Recent progress on preparation and properties of nanocomposites from recycled polymers: a review. Waste Manag. 2013;33:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zare Y, Garmabi H. Nonisothermal crystallization and melting behavior of PP/nanoclay/CaCO3 ternary nanocomposite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012;124:1225–1233. doi: 10.1002/app.35134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danilovtseva EN, Aseyev V, Belozerova OY, Zelinskiy SN, Annenkov VV. Bioinspired thermo-and pH-responsive polymeric amines: multimolecular aggregates in aqueous media and matrices for silica/polymer nanocomposites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;446:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mekki A, Samanta S, Singh A, Salmi Z, Mahmoud R, Chehimi MM, Aswal DK. Core/shell, protuberance-free multiwalled carbon nanotube/polyaniline nanocomposites via interfacial chemistry of aryl diazonium salts. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;418:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamed A, Anas AK, Bakar SA, Ardyani T, Zin WMW, Ibrahim S, Sagisaka M, Brown P, Eastoe J. Enhanced dispersion of multiwall carbon nanotubes in natural rubber latex nanocomposites by surfactants bearing phenyl groups. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;455:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nezakati T, Tan A, Seifalian AM. Enhancing the electrical conductivity of a hybrid POSS–PCL/graphene nanocomposite polymer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;435:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y, Ng KM, Chan C-M, Sun G, Wu J. High-impact polystyrene/halloysite nanocomposites prepared by emulsion polymerization using sodium dodecylsulfate as surfactant. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;358:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leng J, Lau AKT. Multifunctional polymer nanocomposites. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang Y-C, Ciou J-R. Effects of surface chemical states of carbon nanotubes supported Pt nanoparticles on performance of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2011;36:6826–6831. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.02.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zemen Y, Schulz SC, Trommler H, Buschhorn ST, Bauhofer W, Schulte K. Comparison of new conductive adhesives based on silver and carbon nanotubes for solar cells interconnection. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2013;109:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2012.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peretz S, Regev O. Carbon nanotubes as nanocarriers in medicine. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;17:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2012.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman MM, Hussein MA, Alamry KA, Al-Shehry FM, Asiri AM. Sensitive methanol sensor based on PMMA-G-CNTs nanocomposites deposited onto glassy carbon electrodes. Talanta. 2016;150:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fam D, Palaniappan A, Tok A. A review on technological aspects influencing commercialization of carbon nanotube sensors. Sens. Actuators B. 2011;157:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2011.03.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussein MA, Abu-Zied BM, Asiri AM. The role of mixed graphene/carbon nanotubes on the coating performance of G/CNTs/epoxy resin nanocomposites. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016;11:7644–7659. doi: 10.20964/2016.09.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanahan AE, Sullivan JA, Mc-Namara M, Byrne HJ. Preparation and characterization of a composite of gold nanoparticles and single-walled carbon nanotubes and its potential for heterogeneous catalysis. New Carbon Mater. 2011;26:347–355. doi: 10.1016/S1872-5805(11)60087-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman JN, Khan U, Blau WJ. Small but strong: a review of the mechanical properties of carbon nanotube–polymer composites. Carbon. 2006;44:1624–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2006.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sgobba V, Guldi DM. Carbon nanotubes-electronic/electrochemical properties and application for nanoelectronics and photonics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:165–184. doi: 10.1039/B802652C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kneipp K, Moskovits M, Kneipp H. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering: physics and applications. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kneipp K, Kneipp H, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering and biophysics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2002;14:R597–R624. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/14/18/202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Said WA, Kim SU, Choi J-W. Monitoring in vitro neural stem cell differentiation based on surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy using a gold nanostar array. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015;3:3848. doi: 10.1039/C5TC00304K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An J-H, El-Said WA, Choi J-W. Surface enhanced Raman scattering of neurotransmitter release in neuronal cells using antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011;11:1585–1588. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.An J-H, El-Said WA, Yea C-H, Kim T-H, Choi J-W. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering of dopamine on self-assembled gold nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011;11:4424–4429. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Said WA, Kim T-H, Yea C-H, Kim HC, Choi J-W. Fabrication of gold nanoparticle modified ITO substrate to detect β-amyloid using surface-enhanced Raman scattering. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011;11:768–772. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Said WA, Kim T-H, Kim HC, Choi J-W. Detection of effect of chemotherapeutic agents to cancer cells on gold nanoflower patterned substrate using surface enhanced Raman scattering and cyclic voltammetry. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010;26:1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asiri AM, Hussein MA, Abu-Zied BM, Hermas AA. Enhanced coating properties of Ni-La-ferrites/epoxy resin nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2015;36:1875–1883. doi: 10.1002/pc.23095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asiri AM, Hussein MA, Abu-Zied BM, Hermas AA. Effect of NiLaxFe2-xO4 nanoparticles on the thermal and coating properties of epoxy resin composites. Compos. Part B. 2013;51:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriche R, Prolongo SG, Sánchez M, Jiménez-Suárez A, Sayagués MJ, Ureña A. Morphological changes on graphene nanoplatelets induced during dispersion into an epoxy resin by different methods. Composites. 2016;72:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Babu HV, Zhao J, Goñi-Urtiaga A, Sainz R, Ferritto R, Pita M, Wang D-Y. Effect of Cu-doped graphene on the flammability and thermal properties of epoxy composites. Composites Part B. 2016;89:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaman I, Kuan HC, Meng QS, Michelmore A, Kawashima N, Pitt T, Zhang LQ, Gouda S, Luong L, Ma J. A facile approach to chemically modified graphene and its polymer nanocomposites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22(13):2735–2743. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201103041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong L-X, Zhao L, Tang L-C, Liu H-Y, Mai Y-W. Balanced electrical, thermal and mechanical properties of epoxy composites filled with chemically reduced graphene oxide and rubber nanoparticles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015;121:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan Y-J, Tang L-C, Gong L-X, Yan D, Li Y-B, Wu L-B, Jiang J-X, Lai G-Q. Grafting of epoxy chains onto graphene oxide for epoxy composites with improved mechanical and thermal properties. Carbon. 2014;69:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.12.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wan Y-J, Yang W-H, Yu S-H, Sun R, Wong C-P, Liao W-H. Covalent polymer functionalization of graphene for improved dielectric properties and thermal stability of epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016;122:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu Z, Di H, Ma Y, Lv L, Pan Y, Zhang C. Yi He, Fabrication of graphene oxide–alumina hybrids to reinforce the anti-corrosion performance of composite epoxy coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015;351:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikolic G, Zlatkovic S, Cakic M, Cakic S, Lacnjevac C, Rajic Z. Fast fourier transform IR characterization of epoxy GY systems cross-linked with aliphatic and cycloaliphatic EH polyamine adducts. Sensors. 2010;10:684–696. doi: 10.3390/s100100684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zlatković S, Rašković L, Nikolić G, Stamenković J. Investigation of emulsified hydrous epoxy systems. Facta Universitatis Series. 2005;2:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naebe M, Wang J, Amini A, Khayyam H, Hameed N, Li LH, Chen Y, Fox B. Mechanical property and structure of covalent functionalized graphene/epoxy nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4375. doi: 10.1038/srep04375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang X, Wu K, He M, Ye Z, Tang S, Jiang Z. Facile synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide/copper composites using freeze-drying and spark plasma sintering. Mater. Lett. 2016;166:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.12.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elashmawi IA, AIatawia NS, Elsayed NH. Preparation and characterization of polydsttmer nanocomposites based on PVDF/PVC doped with graphene nanoparticles. Results Phys. 2017;7:636–640. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2017.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Razzazan A, Atyabi F, Kazemi B, Dinarvand R. In vivo drug delivery of gemcitabine with PEGylated single-walled carbon nanotubes. Mat. Sci. Eng. C. 2016;62:614. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, Xing W, Feng X, Yu B, Lu H, Song L, Hu Y. The effect of metal oxide decorated graphene hybrids on the improved thermal stability and the reduced smoke toxicity in epoxy resins. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;250:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.01.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.An J-E, Jeong YG. Structure and electric heating performance of graphene/epoxy composite films. Eur. Polym. J. 2013;49:1322–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X, Alloul O, He Q, Zhu J, Verde MJ, Li Y, Wei S, Guo Z. Strengthened magnetic epoxy nanocomposites with protruding nanoparticles on the graphene nanosheets. Polymer. 2013;54:3594–3604. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.04.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hussein MA, Abu-Zied BM, Asiri AM. Fabrication of EPYR/GNP/MWCNT carbon-based composite materials for promoted epoxy coating performance. RSC Adv. 2018;8:23555–23566. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03109F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katowah D, Hussein MA, Alam MM, Sobahi TR, Gabal MA, Asiri AM, Rahman MM. Poly(pyrrole-co-o-toluidine) wrapped CoFe2O4/R(GO–OXSWCNTs) ternary composite material for Ga3+ sensing ability. RSC Adv. 2019;9:33052–33070. doi: 10.1039/C9RA03593A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katowah D, Hussein MA, Rahman MM, Alsulami QA, Alam MM, Asiri AM. Fabrication of hybrid PVA-PVC/SnZnOx/SWCNTs nanocomposites as Sn2+ ionic probe for environmental safety. Polym. Plast. Technol. Mater. 2019;59:642–657. doi: 10.1080/25740881.2019.1673409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.A. Tager, Physical chemistry of polymers: Mir, Moscow, 1972.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.