Abstract

Babesia microti, the main pathogen causing human babesiosis, has been reported to exhibit resistance to the traditional treatment of azithromycin + atovaquone and clindamycin + quinine, suggesting the necessity of developing new drugs. The methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, a unique pathway in apicomplexan parasites, was shown to play a crucial function in the growth of Plasmodium falciparum. In the MEP pathway, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) is a rate-limiting enzyme and fosmidomycin (FSM) is a reported inhibitor for this enzyme. DXR has been shown as an antimalarial drug target, but no report is available on B. microti DXR (BmDXR). Here BmDXR was cloned, sequenced, analyzed by bioinformatics, and evaluated as a potential drug target for inhibiting the growth of B. micorti in vitro. Drug assay was performed by adding different concentrations of FSM in B. microti in vitro culture. Rescue experiment was done by supplementing 200 μM isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) or 5 μM geranylgeraniol (GG-ol) in the culture medium together with 5 μM FSM or 10 μM diminazene aceturate. The results indicated that FSM can inhibit the growth of B. microti in in vitro culture with an IC50 of 4.63 ± 0.12 μM, and growth can be restored by both IPP and GG-ol. Additionally, FSM is shown to inhibit the growth of parasites by suppressing the DXR activity, which agreed with the reported results of other apicomplexan parasites. Our results suggest the potential of DXR as a drug target for controlling B. microti and that FSM can inhibit the growth of B. microti in vitro.

Keywords: Babesia microti, fosmidomycin, DXR, isoprenoid, babesiosis, methylerythritol 4-phosphate

Introduction

Parasites of the genus Babesia are prevalent apicomplexan pathogens transmitted by ticks and infect many mammalian and avian species (Yabsley and Shock, 2013). Human babesiosis is primarily caused by the parasite Babesia microti, with most people being infected by ticks and some by blood transfusion (Goethert et al., 2003; Hildebrandt et al., 2007; Young et al., 2012). The infection is characterized by fever and hemolytic anemia and can result in death in severe cases from complications, such as heart failure, respiratory distress, and pulmonary edema (Rosner et al., 1984). Due to the increasing number of people infected with Babesia, B. microti-related infection has been classified as a nationally notifiable disease since 2011 by the Center for Disease Control (United States) (Herwaldt et al., 2011). Babesiosis is usually treated with atovaquone and azithromycin, but resistance to these drugs has been reported (Krause et al., 2000; Wormser et al., 2010; Simon et al., 2017). Therefore, it is very urgent to develop new anti-Babesia drugs.

Apicomplexan parasites contain a vestigial plastid called the apicoplast (McFadden et al., 1996), which plays an important role in the biosynthesis of isoprenoid precursors, fatty acids, and part of the heme (Ralph et al., 2004). However, the apicoplast of Babesia is only found in isoprenoid biosynthesis (Brayton et al., 2007; Silva et al., 2016). Apicomplexan parasites utilize the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway to get isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) (Imlay and Odom, 2014), which are the basic units of synthetic isoprenoids and essential for parasite growth (Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007).

Isoprenoids comprise a large family and have an important function in membrane structure, cellular respiration, and cell signaling (Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). IPP in living organisms can be synthesized by two pathways [mevalonate (MVA) pathway and MEP pathway] (Odom, 2011). Humans use the MVA pathway to synthesize IPP from acetyl-CoA (Endo, 1992). However, there is no MVA pathway in the genus of Apicomplexa, which thus synthesizes IPP by the MEP pathway (Cassera et al., 2004). The MEP pathway was first reported to be present in Plasmodium falciparum in 1999 (Jomaa et al., 1999). With the deepening of research, the MEP pathway was found to be crucial for parasites (Cassera et al., 2004). For instance, the deoxyxylose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) of P. falciparum was shown to contribute to the erythrocyte stage, and inhibiting the DXR activity reduced the growth and the development of the parasites (Odom and Van Voorhis, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011). Additionally, by knocking out the DXR genes of Toxoplasma gondii, the parasites were found unable to survive, proving the essentiality of the MEP pathway for their survival (Nair et al., 2011).

The first dedicated step in MEP isoprenoid biosynthesis is accomplished by the bifunctional enzyme DXR (Imlay and Odom, 2014). DXR is competitively inhibited in vitro by the antibiotic fosmidomycin (Koppisch et al., 2002; Sangari et al., 2010). Fosmidomycin has been shown to be a clinical prospect for antimalarial drugs due to its inhibition on the recombinant Plasmodium DXR to kill Plasmodium, and the current clinical trial of malaria treatment with clindamycin is in phase II (Olliaro and Wells, 2009). Babesia and Plasmodium have many similarities, and they both live in red blood cells (RBCs). In this study, we have found that B. microti DXR (BmDXR) has conserved binding sites of fosmidomycin (FSM), and FSM can inhibit the growth of B. microti in vitro, suggesting its potential as a new anti-Babesia drug.

Materials and Methods

Parasites

A B. microti strain ATCC PRA-99TM® (Ruebush and Hanson, 1979) was obtained from the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Shanghai, China), and maintained in our laboratory (State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong Agricultural University, China). The parasites were isolated at parasitemia of 30–40% as determined by Giemsa staining of thin blood smears.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from infected blood by using the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). RNA concentration was measured by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo, China). The cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of the total RNA using a PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit with gDNA eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China).

Cloning of the BmDXR Gene

Primer pairs of BmDXR were designed based on the sequences of the B. microti strain R1: BmDXR-F (5’-ATGACAAATTATTT AAAACTC-3’) and BmDXR-R (5’-TTAACACTTAATTTTTTT TGC-3’). Complete sequences of the BmDXR were amplified by PCR from cDNA separately. The PCR reaction was performed at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 47°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min 30 s, and finally at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified and ligated into the cloning vector pEASY-Blunt (Trans, Beijing, China). Three positive colonies of each gene were sent for sequencing analysis by Invitrogen (Shanghai, China).

Sequence Analysis

The amino acid sequence of BmDXR was aligned with the selected amino acid sequences from other organisms by MAFFT online1, then edited by BioEdit v7.25, and phylogenetically analyzed by using the Maximum Likelihood method in MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., 2016). The structure of BmDXR was predicted by SWISS-MODEL2 (Guex et al., 2009; Bienert et al., 2017; Waterhouse et al., 2018). The 3D structure of BmDXR was virtually docked with FSM through Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) version 2014.09 (Chemical Computing Group).

B. microti Short-Term in vitro Cultivation

To cultivate B. microti in vitro, infected RBCs and healthy mouse RBCs were collected in tubes containing EDTA-2K solution (solution/RBCs = 1:9; 10% EDTA-2K), followed by centrifugation to pellet the cells at 1,000 g for 10 min at room temperature), two washes in PSG solution, resuspension of RBCs in the same volume of PSG + G solution, and storage at 4°C until use. The infected RBCs were diluted with healthy RBCs to 3%, followed by cultivation in the presence of HL-1 supplemented with 10 μg/mg AlbuMax I (Gibco Life Technologies), 1% HB101 (Irvine Scientific, Shanghai, China), 200 μM L-glutamine (ATLANTA Biologicals, Shanghai, China), 2% antibiotic/antimycotic 100 × (Corning, Shanghai, China), and 20% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a microaerophilous stationary phase (5% CO2, 2% O2, and 93% N2) (Abraham et al., 2018).

Fosmidomycin Treatment and Rescue Assay

Drug stock solutions of FSM (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, Chain) and diminazene aceturate (DA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, Chain) were prepared in sterile water. Geranylgeraniol (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, Chain) stocks were prepared in 100% ethanol. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate triammonium salt solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, Chain) was used directly without any additional treatment. For the growth inhibition assay, B. microti cultures (20 μl of RBCs plus 100 μl of culture medium) were grown in 96-well flat-bottomed plates, and the susceptibility of B. microti in vitro to FSM was evaluated at concentrations up to 500 μM. The results were further confirmed by the IC50 values calculated using the Käber method. All the experiments were repeated three times.

In the rescue experiments, IPP or geranylgeraniol (GG-ol, alcohol of geranylgeranyl diphosphate) was added to the medium containing different drugs. IPP is one of the products in the MEP pathway (He et al., 2018), and GG-ol is the alcohol analog of the downstream isoprenoids (Yeh and DeRisi, 2011; Imlay and Odom, 2014). DA was used as a positive control, and ethanol was used as a negative control. The group of control is only medium. Each drug test was performed in triplicate.

In order to test the parasitemia, three smears were prepared from each well after 72 h of incubation. After air-drying, thin blood smears were fixed with methanol, followed by staining with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China), and measuring the parasitemia by microscopy. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 (San Diego, CA, United States) by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. The results are shown as mean ± SD (NS, P > 0.05 not significant at 5%; ∗P < 0.05 significant at 5%; ∗∗P < 0.01 significant at 1%; and ∗∗∗ P < 0.001 significant at 0.1%; error bars represent the standard deviations).

Results

Cloning and Characterization of B. microti DXR

The open reading frame of BmDXR was cloned from B. microti PRA99 cDNA by conventional PCR. The results showed that BmDXR is 1,401 bp in length, encoding 466 amino acids with a predicted size of 51.8 kDa. The sequence was submitted to GenBank, with accession number MK673989. BLASTn indicated that BmDXR PRA99 (MK673989) is identical to that of B. microti R1 strain (XP_021338225).

Bioinformatic Analysis

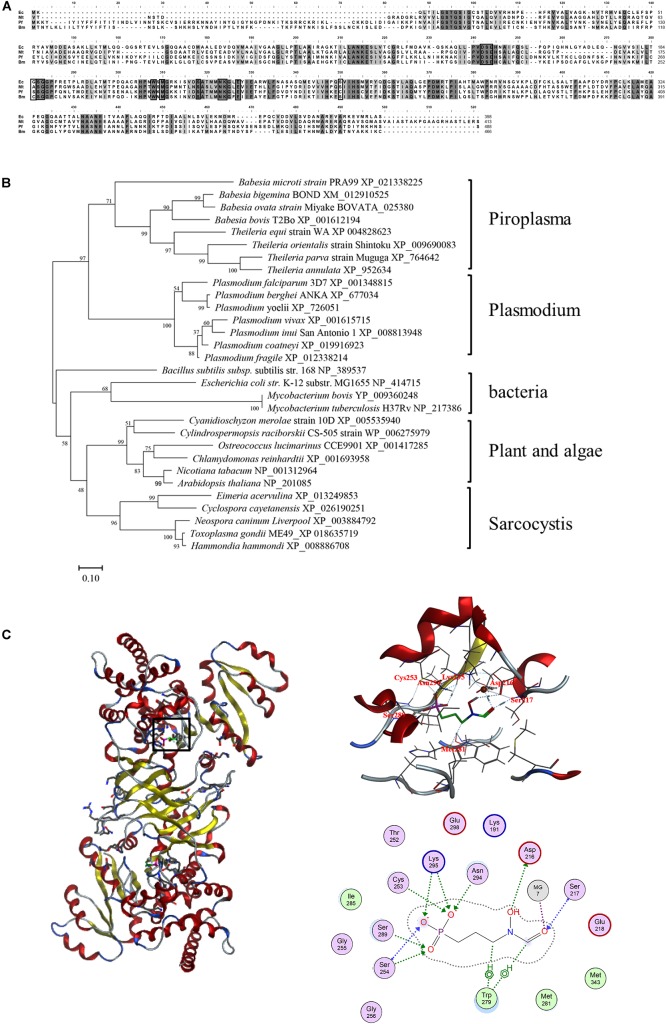

The obtained BmDXR sequence was characterized by bioinformatic analysis. SignalP4.1 analysis indicated that BmDXR has a 22-amino-acid signal peptide in N-terminus3, and a 48-amino-acid transit peptide right after the signal peptide. The amino acid sequence of BmDXR was aligned with the DXR amino acid sequences of other apicomplexan parasites by MAFFT. The results showed that BmDXR has the highest similarity to the DXR sequence of P. falciparum (AAD03739) with a percent identity of 41.71%, and the lowest similarity to that of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (NP_217386), with a percent identity of 36.59% (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Bioinformatics analysis of the amino acid sequence of DXR. (A) Multiple alignment of DXR amino acid sequences. Ec, Escherichia coli (NP_414715); Mt, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (NP_217386); Pf, Plasmodium falciparum (AAD03739); Bm, Babesia microti (XP_021338225). Black shading indicates a similarity in four or in more than four species; gray shading indicates a similarity in three species. Black pane indicates the reported fosmidomycin binding site. (B) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on DXR amino acid sequences. The organism names and sequence accession numbers are indicated. (C) Prediction of the structure of BmDXR by SWISS-MODEL. The 3D structure of BmDXR is virtually docked with FSM through MOE2014.0901, and FSM can form hydrogen bonds with Ser217, Asp216, Cys253, Met281, Ser289, Asn294, and Lys295 of BmDXR.

DXR amino acid sequences were characterized by phylogenetic analysis with MEGA6, and B. microti was shown to fall in the piroplasma clade in the same category of Plasmodium. In contrast, bacteria, plant, algae, and sarcocystis are grouped in the same category (Figure 1B). In the piroplasma clade, B. microti is significantly different from the other species, including B. bigemina, B. ovata, B. bovis, T. equi, T. orientalis, T. parva, and T. annulata.

The 3D structure of BmDXR was predicted by SWISS-MODEL, and BmDXR is shown as a dimeric structure with a metal ion binding site consisting of amino acids D216, E218, and E298. The 3D structure of BmDXR was virtually docked with FSM using MOE2014.0901. The results showed that FSM can form hydrogen bonds with Ser217, Asp216, Cys253, Met281, Ser289, Asn294, and Lys295 of BmDXR (Figure 1C).

Fosmidomycin Inhibits the Growth of B. microti in vitro

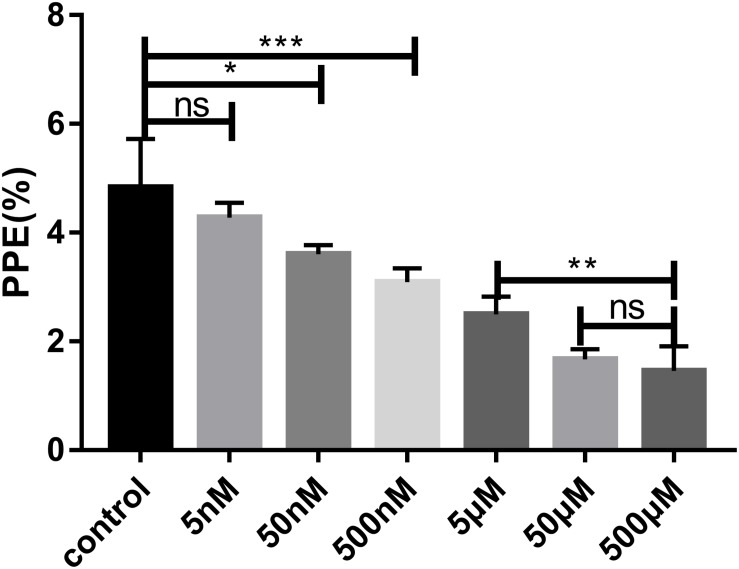

The effect of FSM on the growth of B. microti in vitro was tested by adding different concentrations of FSM into the in vitro culture medium at an initial percent parasitized erythrocytes (PPE) of 3%. Parasitemia was counted at 72 h post-treatment by microscopy. The parasitemia of the FSM groups is 4.27 ± 0.28%, 3.60 ± 0.16%, 3.09 ± 0.25%, 2.49 ± 0.33%, 1.67 ± 0.18%, and 1.45 ± 0.45% at the concentration of 5, 50, and 500 nM and 5, 50, and 500 μM, respectively, in contrast to an increase from 3% to 4.83 ± 0.8% for the negative control group (the group without drug) after 72 h of culture. After the 72-h treatment, the parasitemia is significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the 50 nM FSM group than in the negative control group, with a significant difference (P < 0.01) between 5 and 50 or 500 nm FSM groups, but no difference between the 50- and 500-μM FSM groups (Figure 2). The test results indicated that the drug efficacy is dose dependent, and FSM could not completely inhibit the growth of B. microti even at a drug concentration as high as 500 μM (inhibition rate of 70%). Compared to the negative control group, FSM exhibited a potential anti-B. microti activity at a low micromolar concentration, with an IC50 of 4.63 ± 0.12 μM.

FIGURE 2.

Parasitemia of different drug concentrations after 72 h of treatment. Evaluation of the susceptibility of B. microti in vitro to fosmidomycin at concentrations from 5 to 500 μM. Giemsa staining assay at 72 h after the addition of the drug. PPE, pollen productivity estimate; Ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

IPP and GG-ol Can Rescue B. microti Treated by Fosmidomycin

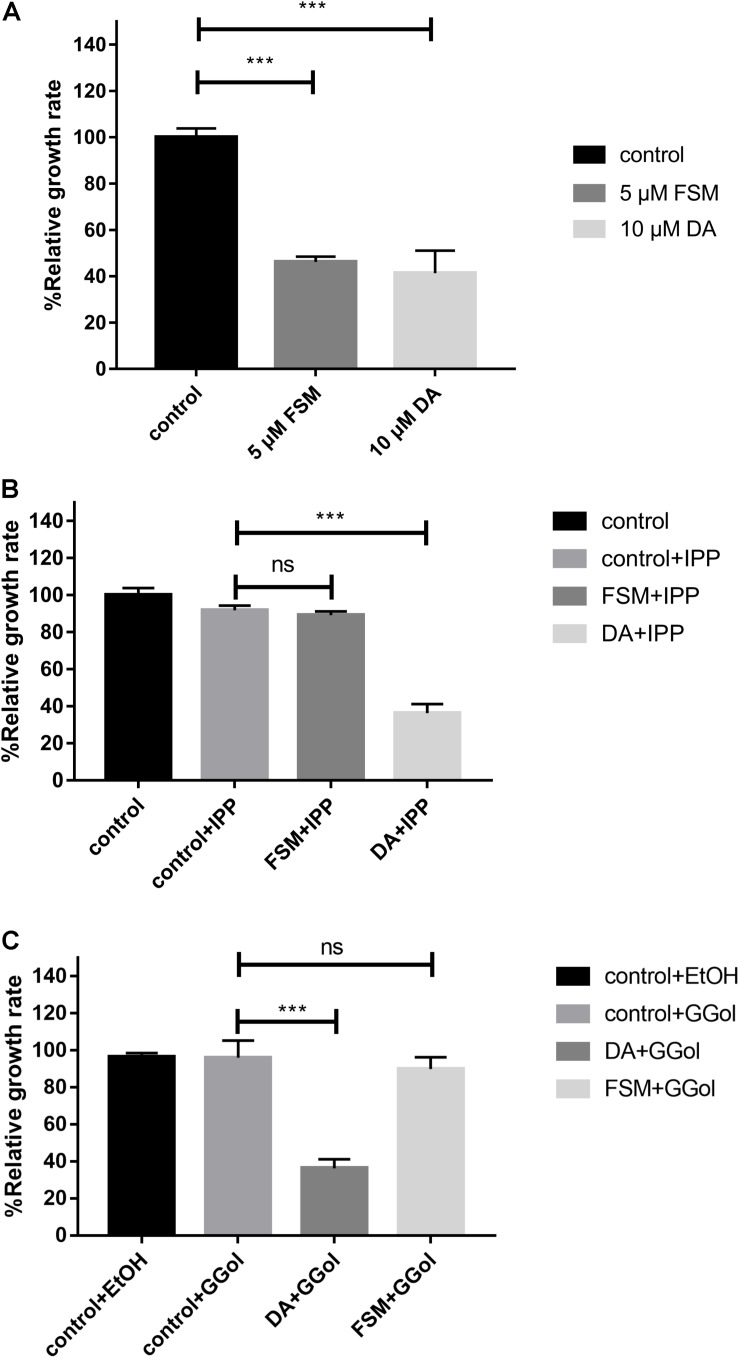

The inhibition of FSM on the growth of B. mitroti was investigated through rescue experiments in B. microti in vitro cultivation with 200 μM IPP and 5 μM GG-ol added separately into 5 μM FSM and 10 μM DA using the latter as a positive control. The 5 μM FSM and 10 μM DA showed 53.8 and 58.6% inhibition on the growth of the parasites (Figure 3A) in the rescue experiment. The growth in 5 μM FSM could be restored by adding 200 μM IPP or 5 μM GG-ol into culture media as indicated by having no difference (P < 0.001) in the relative growth rate among FSM + IPP, GG-ol, and the control (Figures 3B,C). However, the growth in 10 μM DA could not be rescued by adding IPP or GG-ol, as shown by a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the relative growth rate among DA + IPP, DA + GG-ol, and the control [ANOVA, F(2, 6) = 259.2, P < 0.0001; ANOVA, F(2, 6) = 65.1, P < 0.0001] (Figures 3B,C).

FIGURE 3.

IPP and GGol can rescue B. microti treated by fosmidomycin and Giemsa staining assay at 72 h after the addition of the drugs. (A) Effect of 5 μM fosmidomycin and 10 μM diminazene aceturate on the growth of B. microti in vitro. The group of control is only medium. (B) Rescue of B. microti by adding isopentenyl pyrophosphate. (C) Rescue of B. microti by adding geranylgeraniol. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

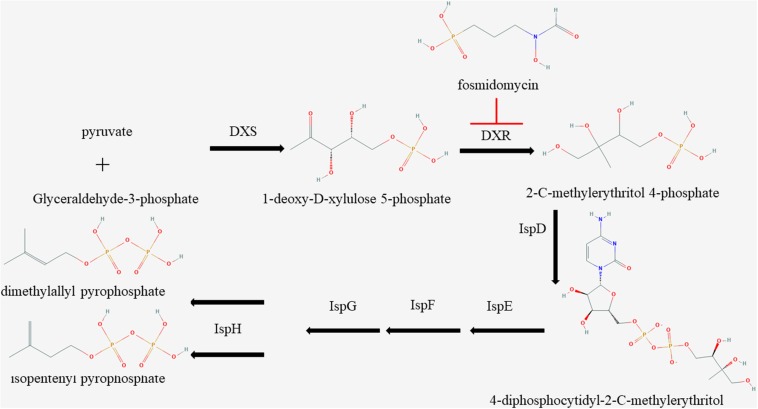

The MEP pathway, an essential route in apicomplexan parasites, plays a vital role in the growth of parasites by synthesizing IPP (Imlay and Odom, 2014); however, very few effective inhibitors have been studied. Currently, the MEP inhibitors with lower IC50 for Plasmodium are FSM and 1R, 3S MMV008138 (Ghavami et al., 2018). DXR is the second and also a rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway (Imlay and Odom, 2014). The inhibitors of DXR enzymes, such as FSM, suppress the synthesis of IPP in the MEP pathway of multiple organisms in vitro (Figure 4; Jomaa et al., 1999). It has been reported that FSM can inhibit B. divergen, B. bovis, and B. orientalis in vitro (Baumeister et al., 2011; Caballero et al., 2012; He et al., 2018). As shown by the reported P. falciparum and M. tuberculosis crystal structures of inhibitor-free and FSM-bound complete quaternary complexes of DXR (Mac Sweeney et al., 2005; Andaloussi et al., 2011; Umeda et al., 2011), a large cleft was closed between NADPH-binding and catalytic domains upon inhibitor binding, which means that FSM inhibits DXR activity by competing with DOXP. The FSM binding site is conservative, and BmDXR is similar in structure to PfDXR and EcDXR. We speculate that FSM can inhibit the DXR activity in B. microti due to its inhibition on the growth of B. microti in in vitro culture with an FSM IC50 value of 4.63 ± 0.12 μM, which is higher than that of B. bovis and B. bigemina (3.87 and 2.4 μM, respectively) (Sivakumar et al., 2008). The growth of B. microti can be rescued by adding IPP or GG-ol in the culture medium, which agreed with the report that GG-ol can rescue the growth of B. orientalis inhibited by FSM (He et al., 2018). These results further suggest that FSM inhibits B. microti growth by suppressing the MEP pathway. It is reported that B. microti, an obligate parasite of red blood cells (Silva et al., 2016), obtains most of the nutrition materials for parasite survival from host red blood cells, but it cannot obtain IPP from host cells due to the small amount of IPP in RBCs (Wiback and Palsson, 2002). In this case, FSM may inhibit the growth of B. microti by suppressing the synthesis of IPP.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic of isoprenoid metabolism through the non-mevalonate pathway. The methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway is a unique route to isoprenoid biosynthesis in apicomplexan, and fosmidomycin is a specific inhibitor to 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase.

FSM can cause the death of P. falciparum in the first life cycle (Howe et al., 2013), but we failed to observe the death of B. microti after 24 h of treatment at 5 μM FSM. According to the results of Giemsa staining (Supplementary Figure S1), we selected the parasites in the period of merozoites and compared their morphologies. All the merozoites in the control group have an obvious contour and a complete shape, while those treated by FSM have lost their contour and complete shape which, however, can be recovered upon addition of IPP or GG-ol in the medium. This is consistent with the observation in B. bovis and B. bigemina treated with FSM, with obvious changes in the shape of the parasites (Sivakumar et al., 2008). These results indicate that IPP is important for Babesia to keep a normal shape. Meanwhile, the merozoites treated by DA present a pointed shape, which could not be restored to a normal shape after adding IPP or GG-ol. These morphologies indicate a milder efficacy of FSM than DA because DA made the merozoites of B. microti point-like, while FSM caused the parasite to lose its normal form. FSM-treated P. falciparum was shown to reduce protein prenylation, leading to marked defects in food vacuolar morphology and integrity (Howe et al., 2013). However, no food vacuole has been reported in B. microti (Rudzinska et al., 1976), suggesting that the impact of FSM on B. microti may be different from its influence mechanism on malaria parasites.

Traditionally, azithromycin + atovaquone was used to treat babesiosis in humans and clindamycin + quinine as a treatment strategy for patients with resistance to atovaquone (Simon et al., 2017). Meanwhile, many patients have adverse reactions to chloroquine (Krause et al., 2000; Rozej-Bielicka et al., 2015). Generally, traditional treatments cannot eliminate B. microti parasitemia completely, suggesting the high recurrence potential of B. microti. Despite being a safe and effective inhibitor, FSM has some limitations to clinical applications. First of all, it is an unmodified compound which is very costly. Secondly, FSM has a poor pharmacokinetics profile with a plasma half-life of 3.5 h (Na-Bangchang et al., 2007); it will need multiple shots for clinic use. This limitation of FSM can be solved by drug modification. For example, FR9008 is a derivative of FSM, which has a better effect on P. falciparum than FSM. Currently, it is necessary to improve the ability of FSM in entering cells and extend its half-life for clinical applications. We believe that the limitations of FSM can be overcome by drug modification. For drug development, modified drugs have better clinical results; for example, dihydroartemisinin has a better effect than artemisinin in treating Plasmodium (Li et al., 1983). About combination therapy, clindamycin + FSM can play a better effect in the treatment of Plasmodium (Borrmann et al., 2006), but clindamycin has less effect to B. microti in vitro (Lawres et al., 2016). Other drugs could be used as combination therapy with FSM if required. Our future work will focus on modifying FSM and the combination therapy of FSM.

Conclusion

The MEP pathway is a favorable target for drug development. In this study, it is shown that FSM can inhibit the growth of B. microti in vitro, which can be rescued by a medium supplemented with IPP or GG-ol. These results indicate that DXR is a potential drug target for designing anti-Babesia drugs and that the DXR function and FSM structure contribute to the design of such drugs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number MK673989.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Scientific Ethic Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (permit number: HZAUMO-2017-040). All mice were handled in accordance with the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China.

Author Contributions

SW, LH, and JZ designed the study and wrote the draft of the manuscript. ML, XL, LY, ZN, QL, XA, YA, QL, JC, and YT performed the experiments and analyzed the results. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- DXR

1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase

- FSM

fosmidomycin

- DA

diminazene Aceturate

- IPP

isopentenyl pyrophosphate

- GG-ol

geranylgeraniol

- ORF

open reading frame

- MEP

2-C-methylerythritol 4-phosphate

- IC50

half-maximum inhibition concentration

- PPE

percent parasitized erythrocytes.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31772729), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0501201), the National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (2015CB150302), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2017CFA020).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2020.00247/full#supplementary-material

Morphology of merozoites cultured in vitro for 72 h. 5 μM FSM and 10 μM DA caused changes in merozoite morphology, and 200 μM IPP or 5 μM GG-ol can restore merozoite morphology treated by FSM.

References

- Abraham A., Brasov I., Thekkiniath J., Kilian N., Lawres L., Gao R., et al. (2018). Establishment of a continuous in vitro culture of Babesia duncani in human erythrocytes reveals unusually high tolerance to recommended therapies. J. Biol. Chem. 293 19974–19981. 10.1074/jbc.AC118.005771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaloussi M., Henriksson L. M., Wieckowska A., Lindh M., Bjorkelid C., Larsson A. M., et al. (2011). Design, synthesis, and X-ray crystallographic studies of alpha-aryl substituted fosmidomycin analogues as inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. J. Med. Chem. 54 4964–4976. 10.1021/jm2000085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister S., Wiesner J., Reichenberg A., Hintz M., Bietz S., Harb O. S., et al. (2011). Fosmidomycin uptake into Plasmodium and Babesia-infected erythrocytes is facilitated by parasite-induced new permeability pathways. PLoS One 6:e19334. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert S., Waterhouse A., de Beer T. A., Tauriello G., Studer G., Bordoli L., et al. (2017). The SWISS-MODEL repository-new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D313–D319. 10.1093/nar/gkw1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrmann S., Lundgren I., Oyakhirome S., Impouma B., Matsiegui P. B., Adegnika A. A., et al. (2006). Fosmidomycin plus clindamycin for treatment of pediatric patients aged 1 to 14 years with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 2713–2718. 10.1128/aac.00392-396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayton K. A., Lau A. O., Herndon D. R., Hannick L., Kappmeyer L. S., Berens S. J., et al. (2007). Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 3 1401–1413. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero M. C., Pedroni M. J., Palmer G. H., Suarez C. E., Davitt C., Lau A. O. (2012). Characterization of acyl carrier protein and LytB in Babesia bovis apicoplast. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 181 125–133. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassera M. B., Gozzo F. C., D’Alexandri F. L., Merino E. F., del Portillo H. A., Peres V. J., et al. (2004). The methylerythritol phosphate pathway is functionally active in all intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 279 51749–51759. 10.1074/jbc.M408360200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo A. (1992). The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. J. Lipid Res. 33 1569–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon J., Dudareva N. (2007). The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 408–414. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami M., Merino E. F., Yao Z. K., Elahi R., Simpson M. E., Fernandez-Murga M. L., et al. (2018). biological studies and target engagement of the 2- C-Methyl-d-Erythritol 4-Phosphate Cytidylyltransferase (IspD)-Targeting Antimalarial Agent (1 R,3 S)-MMV008138 and analogs. ACS Infect. Dis. 4 549–559. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethert H. K., Lubelcyzk C., LaCombe E., Holman M., Rand P., Smith R. P., et al. (2003). Enzootic Babesia microti in Maine. J. Parasitol. 89 1069–1071. 10.1645/ge-3149rn [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N., Peitsch M. C., Schwede T. (2009). Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis 30(Suppl. 1), S162–S173. 10.1002/elps.200900140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., He P., Luo X., Li M., Yu L., Guo J., et al. (2018). The MEP pathway in Babesia orientalis apicoplast, a potential target for anti-babesiosis drug development. Parasit Vectors 11:452. 10.1186/s13071-018-3038-3037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwaldt B. L., Linden J. V., Bosserman E., Young C., Olkowska D., Wilson M. (2011). Transfusion-associated babesiosis in the United States: a description of cases. Ann. Intern. Med. 155 509–519. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-201110362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt A., Hunfeld K. P., Baier M., Krumbholz A., Sachse S., Lorenzen T., et al. (2007). First confirmed autochthonous case of human Babesia microti infection in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26 595–601. 10.1007/s10096-007-0333-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe R., Kelly M., Jimah J., Hodge D., Odom A. R. (2013). Isoprenoid biosynthesis inhibition disrupts Rab5 localization and food vacuolar integrity in Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot Cell 12 215–223. 10.1128/ec.00073-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay L., Odom A. R. (2014). Isoprenoid metabolism in apicomplexan parasites. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 1 37–50. 10.1007/s40588-014-0006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa H., Wiesner J., Sanderbrand S., Altincicek B., Weidemeyer C., Hintz M., et al. (1999). Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285 1573–1576. 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppisch A. T., Fox D. T., Blagg B. S., Poulter C. D. (2002). E. coli MEP synthase: steady-state kinetic analysis and substrate binding. Biochemistry 41 236–243. 10.1021/bi0118207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause P. J., Lepore T., Sikand V. K., Gadbaw J., Burke G., Telford S. R., et al. (2000). Atovaquone and azithromycin for the treatment of babesiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 343 1454–1458. 10.1056/nejm200011163432004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawres L. A., Garg A., Kumar V., Bruzual I., Forquer I. P., Renard I., et al. (2016). Radical cure of experimental babesiosis in immunodeficient mice using a combination of an endochin-like quinolone and atovaquone. J. Exp. Med. 213 1307–1318. 10.1084/jem.20151519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. L., Gu H. M., Warhurst D. C., Peters W. (1983). Effects of qinghaosu and related compounds on incorporation of [G-3H] hypoxanthine by Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77 522–523. 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90129-90123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Sweeney A., Lange R., Fernandes R. P., Schulz H., Dale G. E., Douangamath A., et al. (2005). The crystal structure of E.coli 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase in a ternary complex with the antimalarial compound fosmidomycin and NADPH reveals a tight-binding closed enzyme conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 345 115–127. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden G. I., Reith M. E., Munholland J., Lang-Unnasch N. (1996). Plastid in human parasites. Nature 381:482. 10.1038/381482a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na-Bangchang K., Ruengweerayut R., Karbwang J., Chauemung A., Hutchinson D. (2007). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of fosmidomycin monotherapy and combination therapy with clindamycin in the treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum malaria. Malar. J. 6:70. 10.1186/1475-2875-6-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S. C., Brooks C. F., Goodman C. D., Sturm A., McFadden G. I., Sundriyal S., et al. (2011). Apicoplast isoprenoid precursor synthesis and the molecular basis of fosmidomycin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Exp. Med. 208 1547–1559. 10.1084/jem.20110039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom A. R. (2011). Five questions about non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002323. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom A. R., Van Voorhis W. C. (2010). Functional genetic analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase gene. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 170 108–111. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olliaro P., Wells T. N. (2009). The global portfolio of new antimalarial medicines under development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 85 584–595. 10.1038/clpt.2009.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph S. A., van Dooren G. G., Waller R. F., Crawford M. J., Fraunholz M. J., Foth B. J., et al. (2004). Tropical infectious diseases: metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 203–216. 10.1038/nrmicro843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner F., Zarrabi M. H., Benach J. L., Habicht G. S. (1984). Babesiosis in splenectomized adults. Review of 22 reported cases. Am. J. Med. 76 696–701. 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90298-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozej-Bielicka W., Stypulkowska-Misiurewicz H., Golab E. (2015). Human babesiosis. Przegl. Epidemiol. 69 489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzinska M. A., Trager W., Lewengrub S. J., Gubert E. (1976). An electron microscopic study of Babesia microti invading erythrocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 169 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruebush M. J., Hanson W. L. (1979). Susceptibility of five strains of mice to Babesia microti of human origin. J. Parasitol. 65 430–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangari F. J., Perez-Gil J., Carretero-Paulet L., Garcia-Lobo J. M., Rodriguez-Concepcion M. (2010). A new family of enzymes catalyzing the first committed step of the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 14081–14086. 10.1073/pnas.1001962107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J. C., Cornillot E., McCracken C., Usmani-Brown S., Dwivedi A., Ifeonu O. O., et al. (2016). Genome-wide diversity and gene expression profiling of Babesia microti isolates identify polymorphic genes that mediate host-pathogen interactions. Sci. Rep. 6:35284. 10.1038/srep35284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. S., Westblade L. F., Dziedziech A., Visone J. E., Furman R. R., Jenkins S. G., et al. (2017). Clinical and molecular evidence of atovaquone and azithromycin resistance in relapsed Babesia microti infection associated with rituximab and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65 1222–1225. 10.1093/cid/cix477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar T., AbouLaila M., Khukhuu A., Iseki H., Alhassan A., Yokoyama N., et al. (2008). In vitro inhibitory effect of fosmidomycin on the asexual growth of Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina. J. Protozool. Res. 18 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Umeda T., Tanaka N., Kusakabe Y., Nakanishi M., Kitade Y., Nakamura K. T. (2011). Molecular basis of fosmidomycin’s action on the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Sci. Rep. 1:9. 10.1038/srep00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., et al. (2018). SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiback S. J., Palsson B. O. (2002). Extreme pathway analysis of human red blood cell metabolism. Biophys. J. 83 808–818. 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75210-75217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser G. P., Prasad A., Neuhaus E., Joshi S., Nowakowski J., Nelson J., et al. (2010). Emergence of resistance to azithromycin-atovaquone in immunocompromised patients with Babesia microti infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 381–386. 10.1086/649859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabsley M. J., Shock B. C. (2013). Natural history of Zoonotic Babesia: role of wildlife reservoirs. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2 18–31. 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E., DeRisi J. L. (2011). Chemical rescue of malaria parasites lacking an apicoplast defines organelle function in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001138. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young C., Chawla A., Berardi V., Padbury J., Skowron G., Krause P. J. (2012). Preventing transfusion-transmitted babesiosis: preliminary experience of the first laboratory-based blood donor screening program. Transfusion 52 1523–1529. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Watts K. M., Hodge D., Kemp L. M., Hunstad D. A., Hicks L. M., et al. (2011). A second target of the antimalarial and antibacterial agent fosmidomycin revealed by cellular metabolic profiling. Biochemistry 50 3570–3577. 10.1021/bi200113y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Morphology of merozoites cultured in vitro for 72 h. 5 μM FSM and 10 μM DA caused changes in merozoite morphology, and 200 μM IPP or 5 μM GG-ol can restore merozoite morphology treated by FSM.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number MK673989.