Abstract

An uncontrolled study with process evaluation was conducted in three U.K. community maternity sites to establish the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a novel breastfeeding peer‐support intervention informed by motivational interviewing (MI; Mam‐Kind). Peer‐supporters were trained to deliver the Mam‐Kind intervention that provided intensive one‐to‐one peer‐support, including (a) antenatal contact, (b) face‐to‐face contact within 48 hr of birth, (c) proactive (peer‐supporter led) alternate day contact for 2 weeks after birth, and (d) mother‐led contact for a further 6 weeks. Peer‐supporters completed structured diaries and audio‐recorded face‐to‐face sessions with mothers. Semistructured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of mothers, health professionals, and all peer‐supporters. Interview data were analysed thematically to assess intervention acceptability. Audio‐recorded peer‐support sessions were assessed for intervention fidelity and the use of MI techniques, using the MITI 4.2 tool. Eight peer‐supporters delivered the Mam‐Kind intervention to 70 mothers in three National Health Service maternity services. Qualitative interviews with mothers (n = 28), peer‐supporters (n = 8), and health professionals (n = 12) indicated that the intervention was acceptable, and health professionals felt it could be integrated with existing services. There was high fidelity to intervention content; 93% of intervention objectives were met during sessions. However, peer‐supporters reported difficulties in adapting from an expert‐by‐experience role to a collaborative role. We have established the feasibility and acceptability of providing breastfeeding peer‐support using a MI‐informed approach. Refinement of the intervention is needed to further develop peer‐supporters' skills in providing mother‐centred support. The refined intervention should be tested for effectiveness in a randomised controlled trial.

Keywords: breastfeeding, feasibility, infant feeding, motivational interviewing, peer‐support, pregnancy

Key messages.

The Mam‐Kind intervention was acceptable and feasible to deliver within NHS maternity services and should be tested for effectiveness in a multicentre randomised controlled trial.

The feasibility study highlighted the need to strengthen strategies for the recruitment and retention of participants.

Practice challenges associated with integration of MI in an information‐rich intervention and variability in peer‐supporter MI skill acquisition have led to intervention refinements.

1. INTRODUCTION

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of breastfeeding peer‐support (BFPS) interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries have demonstrated improvements in breastfeeding maintenance, reducing the risk of nonexclusive breastfeeding by up to 28% (Jolly et al., 2012). However, U.K.‐based RCTs of BFPS interventions have not been found to increase breastfeeding continuation rates (Graffy, Taylor, Williams, & Eldridge, 2004; Jolly et al., 2012; Muirhead, Butcher, Rankin, & Munley, 2006; Watt et al., 2009). There are several possible explanations why the U.K.‐based studies of BFPS have shown no effect. These include the use of low intensity interventions (Graffy et al., 2004; Jolly, Ingram, Freemantle, et al., 2012; McInnes, Love, & Stone, 2000) and a lack of contact with the mother during the first few days after birth (Graffy et al., 2004; Muirhead et al., 2006; Watt et al., 2009), when many women stop breastfeeding (Victora et al., 2016). Some studies reported difficulties in achieving the intended number of contacts, low uptake of the intervention, and low adherence to intervention protocol as possible reasons for lack of effect (Graffy et al., 2004; Jolly, Ingram, Freemantle, et al., 2012; McInnes et al., 2000; Scott, Pritchard, & Szatkowski, 2016).

The literature highlights the need for a proactive intensive face‐to‐face peer support with contact in the antenatal and early postnatal period (Brown et al., 2018). We therefore used a systematic and user‐informed approach to codevelop and characterise a novel motivational interviewing (MI) informed peer‐support intervention for breastfeeding maintenance, which included increased proactive contact during the early postnatal period (self‐citation, removed for peer‐review). MI is a person‐centred counselling approach designed to strengthen internal motivation and promote behaviour change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012a, 2012b). MI may have a role in helping women to continue breastfeeding by increasing their intrinsic motivation to breastfeed and working with any ambivalent feelings they may have (Wilhelm, Flanders Stepans, Hertzog, Callahan Rodehorst, & Gardner, 2006).

Several health care and public health interventions have integrated MI with peer‐support (Abeypala, Chalmers, & Trute, 2014; Allicock et al., 2013; Heisler et al., 2007; Kaye, Johnson, Carr, Alick, & Mindy Gellin RNC, 2012). Studies indicate that lay peer‐supporters can achieve MI proficiency, but report challenges with the development of skills such as reflective listening (see Table 1; Allicock et al., 2013; Kaye et al., 2012). They also find it challenging to change their practice from the expectation of first sharing one's own success stories rather than understanding the needs, goals, and motivations of the participant (Allicock et al., 2013). We took account of these challenges when codesigning the intervention and adjusted the training to concentrate on reflective listening and how to avoid the “righting reflex” (i.e., the desire to fix a situation).

Table 1.

MI skills used by the peer‐supporters

| MI skills | Definition (Miller & Rollnick, 2012b) |

|---|---|

| MI spirit | The spirit of MI encompasses collaboration in all areas of MI practice; eliciting and respecting the client's ideas, perceptions and opinions; eliciting and reinforcing the client's autonomy and choices; and acceptance of the client's decisions. |

| Summary | Summarising what the client has been talking about paying particular attention to any talk in which the client mentions making/thinking about change. |

| Empathy | Empathy involves seeing the world through the client's eyes and showing that you understand them from their perspective. |

| Reflections | To repeat or rephrase what the client has said allowing deeper meaning to the communication. |

| Open questions | Open‐ended questions facilitate a client's response to questions from her own perspective and from the area(s) that are deemed important or relevant. |

| Partnership | Working in collaboration and helping to facilitate a power sharing relationship. |

| Information giving |

Providing information or advice in a manner which emphasises the clients autonomy for example: “I have some information about different breastfeeding positions and I wonder if I might discuss it with you.” (Moyers et al., 2016) |

| MI adherent | This measure is a combination of emphasising autonomy, seeking collaboration, and affirmation (a client's strengths, abilities or efforts to change). |

| MI nonadherent | Confronting the client by directly disagreeing with them, or trying to persuade them to change their behaviour using compelling arguments or self‐discourse without permission. |

| Mother's behaviours | |

| Change talk |

Change talk is defined as statements by the client revealing consideration of, motivation for, or commitment to change. There are different categories of change and sustain talk: ability, desire, reason, need, commitment, activation, and taking steps. For example: Mother: “I think I want to give breastfeeding a try. I know it is really good for my baby's health.” Peer‐supporter: “Your baby is so important to you and you want to provide for him” |

| Sustain talk |

Sustain talk is any statements made by the client in favour of the status quo. For example: Mother: “I'm not sure breastfeeding is right for me as I really want my partner to be involved in feeding baby as well. Peer‐supporter: “Whether you chose to breastfeed is your choice. Are there any ways you can think of in which your partner could be involved in feeding if you decide to breastfeed?” |

Note. MI: motivational interviewing.

In line with Medical Research Council guidance (Craig et al., 2008) for developing and testing complex interventions, we aimed to explore the feasibility and acceptability of providing a MI based BFPS intervention to mothers who were considering breastfeeding. Specifically, we were interested in

the extent to which peer‐supporters utilised MI techniques in their interactions with the mothers they support;

uptake, acceptability, and adherence to Mam‐Kind by mothers;

the number and duration of one‐to‐one contacts with peer‐supporters;

how mothers transition to independence/other sources of support/community based support at the end of the intervention.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The Mam‐Kind study was an uncontrolled multisite feasibility study with an embedded process evaluation.

2.2. The Mam‐Kind intervention

The Mam‐Kind intervention was user informed and designed in collaboration with mothers (n = 14), fathers (n = 3), peer‐supporters (n = 15), and health professionals (n = 14). The behaviour change wheel (Michie, Atkins, & West, 2014) framework was used as a guide in developing the intervention and specifying the proposed mechanisms for change. This is described in full elsewhere (self‐citation, removed for peer‐review).

The Mam‐Kind intervention was characterised by antenatal face‐to‐face contact with a peer‐supporter, contact at 48 hr after birth, proactive alternate day one‐to‐one peer‐supporter led contact for 2 weeks, and mother led contact between 2 and 6 weeks. In our intervention, peer‐supporters were provided with training in MI to equip them with the skills required for MI‐based interventions (Miller & Rollnick, 2012a, 2012b), to provide high quality, mother‐centred interactions when supporting mothers in the context of infant feeding (see Appendix S1 for training outline). These skills are described in Table 1. The training also included breastfeeding information and met all local NHS trust induction policies. The peer‐supporters addressed six objectives in their antenatal contact with mothers and five objectives at each of the postnatal time points (see Table 3). They received supervision from an expert in MI and a midwife, who provided breastfeeding advice.

Table 3.

Content domain analysis: Peer‐supporter sessions and objective addressed at time point

| All time points | Antenatal topics | Postnatal topics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 hr | 3–14 days | 15 days–6 weeks | All postnatal time points | |||||||||||

| Emotional support | Social support | Engage with mothers and start to develop rapport | Information about the programme/what to expect | Information about breastfeeding (getting started) | Agree how peer‐supporter will be informed about birth | Engage with mothers and develop a rapport | Information about breastfeeding (relevant to first few days) | Maintain relationship with mothers (and their supporters) | Information about breastfeeding (relevant to first few weeks) | Provide graded exit from intensive one to one service | Information about breastfeeding (relevant to on‐going feeding) | Address queries or concerns | ||

| Antenatal session |

Peer 04 PID 230 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

|

Peer 07 PID 311 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

|

Peer 08 PID 302 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | — | |

|

Peer 02 PID 109 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | — | |

|

Peer 05 PID 226 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

|

Peer 05 PID 207 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

|

Peer 03 PID 121 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | — | |

|

Peer 06 PID 217 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | — | |

|

Peer 01 PID 103 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

|

Peer 03 PID 101 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

|

Peer 06 PID 202 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | — | |

|

Peer 04 PID 210 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Postnatal session (48 hr) |

Peer 03 PID 121 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | ✓ |

|

Peer 07 PID 308 |

✓ | X | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | ✓ | |

|

Peer 06 PID 205 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | ✓ | |

| Postnatal session (3–14 days) |

Peer 02 PID 108 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ |

|

Peer 06 PID 217 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | |

|

Peer 03 PID 113 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | |

| Postnatal session (15 days–6 weeks) |

Peer 02 PID 112 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Peer 01 PID 119 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Peer 08 PID 315 |

✓ | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | X | ✓ | ✓ | |

Notes. NR: not reported; Peer: peer‐supporter identification number; PID: participant identification.

Key: ✓covered, X not covered,  time appropriate,

time appropriate,  time inappropriate, — not applicable.

time inappropriate, — not applicable.

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Site selection

The study was conducted in three sites in Wales and England. These sites were chosen because they served areas that had high levels of socio‐economic deprivation (as defined by English and Welsh indices of multiple deprivation) and low levels of community breastfeeding rates (less than 70% breastfeeding initiation). All mothers in these areas received usual midwifery and health‐visiting care, including community based antenatal and postnatal care.

2.3.2. Recruitment of mothers

Nineteen community midwives were asked to introduce the study at routine antenatal appointments from 28 weeks gestation onwards to English‐speaking mothers who were considering breastfeeding. Mothers who were unable to provide written informed consent, unable to use conversational English, who did not plan to breastfeed, had a clinical reason that precluded breastfeeding, or had a planned admission to neonatal unit following birth were excluded from the study. Recruitment took place between September and December 2015.

2.3.3. Recruitment and training of peer‐supporters

Six peer‐supporters were recruited to work in two sites that did not have a preexisting intensive paid peer‐support service. These peer‐supporters were employed via the university due to the short duration of the study and supervised by a community midwife who facilitated their integration into the NHS setting. In the third site, the existing BFPS service was modified and delivered by the two existing paid staff. This allowed us to test the feasibility of implementing the intervention within an existing service, which required a shift in the way of working to deliver Mam‐Kind as specified in the context of a research study.

2.4. Data collection

2.4.1. Peer‐supporter in‐field data collection

To obtain data on uptake and adherence, the peer‐supporters completed a diary documenting their contacts with the mothers they were supporting. The diaries provided data on the timing, location, and type of contact (telephone call, text, or face‐to‐face), including who initiated the contact (see Table 3).

Peer‐supporters were asked to audio record all of their face‐to‐face sessions with mothers who had consented to being recorded. A purposive sample of these audio‐recordings were chosen to assess content fidelity to ensure full representation of all key intervention time points (antenatal, 48 hr, 2–13 days and 2–6 weeks). An additional two sessions per peer‐supporter were analysed to assess MI fidelity at the beginning and end of the intervention period.

2.4.2. Quantitative data

Baseline data included socio‐demographic variables, infant feeding intentions, and maternal health and well‐being (Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, generalised anxiety disorder scale [GAD‐2] and EQ‐5D‐5L).

Telephone follow‐up at 10‐days postbirth, women were asked about skin‐to‐skin contact, feeding method and breastfeeding self‐efficacy (breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale short form), support received, and sources of influence (comprehensive list of sources of support/influence rated on a scale of 0 to 4).

Telephone follow‐up at 8–10 weeks postbirth collected data relating to the duration of breastfeeding, breastfeeding attitudes, use of health care professionals or groups, maternal and child health and well‐being.

A telephone 10‐day minimum data‐set questionnaire was completed at 8–10 weeks for participants who could not be contacted by telephone at 10 days.

2.4.3. Qualitative interviews

All eight peer‐supporters, 12 health professionals (two midwives [one midwife who was a high recruiter into the study and one midwife who was a low recruiter, as defined by the supervising midwife], one health visitor, and one service manager from each of the three sites), and 29 mothers took part in semistructured interviews to explore their experiences of the Mam‐Kind intervention. Of the 70 women who took part in the study, 67 consented to take part in the interviews when they enrolled for the study. From these, mothers who were invited for an interview were purposively sampled on the basis of four factors: study site, allocated peer‐supporter, breastfeeding continuation status at 10 days, and level of engagement with the intervention determined by peer‐supporter diary records. All of those who were invited to an interview agreed to take part. The semistructured interviews were conducted via telephone by two experienced qualitative researchers (L. C. and L. M.). The two qualitative researchers on this study came from either a psychology or midwifery background. Both researchers were aware that their backgrounds may influence their interpretation of the data especially the researcher with a midwifery background; however, the use of double coding aimed to mitigate this potential bias. Interviews were facilitated by a topic guide, which included questions on recruitment, intervention delivery and acceptability, and social support. The interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company. The duration of interviews ranged between 15 and 75 min.

2.5. Data analysis

Descriptive summary statistics (frequencies/percentages and means/standard deviations) were tabulated for the Mam‐Kind diary data and the questionnaire data.

Interviews were analysed using inductive thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2014). An initial coding framework for the interview data was developed on the basis of three interviews with participants. The themes were further updated and refined throughout the analysis until all themes were deemed to have been adequately captured. The coding framework was then applied to all the interviews and independently coded by two researchers using NVivo 10. The team discussed any new analytic themes that emerged; these were added to the framework and previous transcripts were recoded accordingly until all the data had been coded.

One researcher used content analysis to analyse audio‐recordings of peer‐support sessions (Clarke & Braun, 2014), facilitated by NVivo 10. The coding framework corresponded to time‐specific objectives, as described in the intervention content guide (see Table 3, first three rows under respective time points). Following the content coding, session content was mapped against the objectives in the intervention content guide to produce a matrix that indicated whether objectives had been met and whether the content of the session was appropriate to the stage of the intervention.

Fidelity to MI was assessed using the MITI 4.2 (Moyers, Rowell, Manuel, Ernst, & Houck, 2016). The MITI 4.2 rating tool comprises a number of count and score variables. This measure was developed and validated to measure MI practitioner's skills. The MITI 4.2 requires the coder to identify the behaviour change focus within the sessions (i.e., breastfeeding) and to assign ratings in relation to whether talk is about the identified behaviour change. “Global” ratings are assigned to each session and are divided into (a) technical: “cultivating change talk,” “softening sustain talk,” and (b) relational: “partnership,” “empathy’ (see Table 1 for description of MI skills). These items are scored on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating more skilful practice. Behaviour count scores are also provided. Although MITI4.2 offers some expert‐led guidance regarding competency thresholds, we did not expect peer‐supporters to reach these thresholds. Rather the assessments were used to understand the extent to which the peer‐supporters were able to develop and use MI in their contacts with the mothers.

We modified our use of the MITI 4.2. Usually the MITI 4.2 MI skills adherence assessment uses a randomly selected continuous 20‐minute segment of recording for coding. However, during intervention sessions, peer‐supporters shifted focus across a number of different topic areas, which meant that there was not necessarily a continuous 20‐minute section in which they talked about “feeding baby,” the identified target behaviour. Therefore, following the content analysis of the audio‐recordings, sections of audio files where the conversation focused on relevant feeding baby, content was identified, and the MITI 4.2 was applied to a 20 min collection of these segments.

2.5.1. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the NHS Health Research Authority, Wales REC 3 Panel, in June 2015 (Reference: 15/WA/0149). All participants provided written informed consent. Health professionals provided audio‐recorded verbal consent prior to interview and consent to use anonymised quotations in publications.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant recruitment

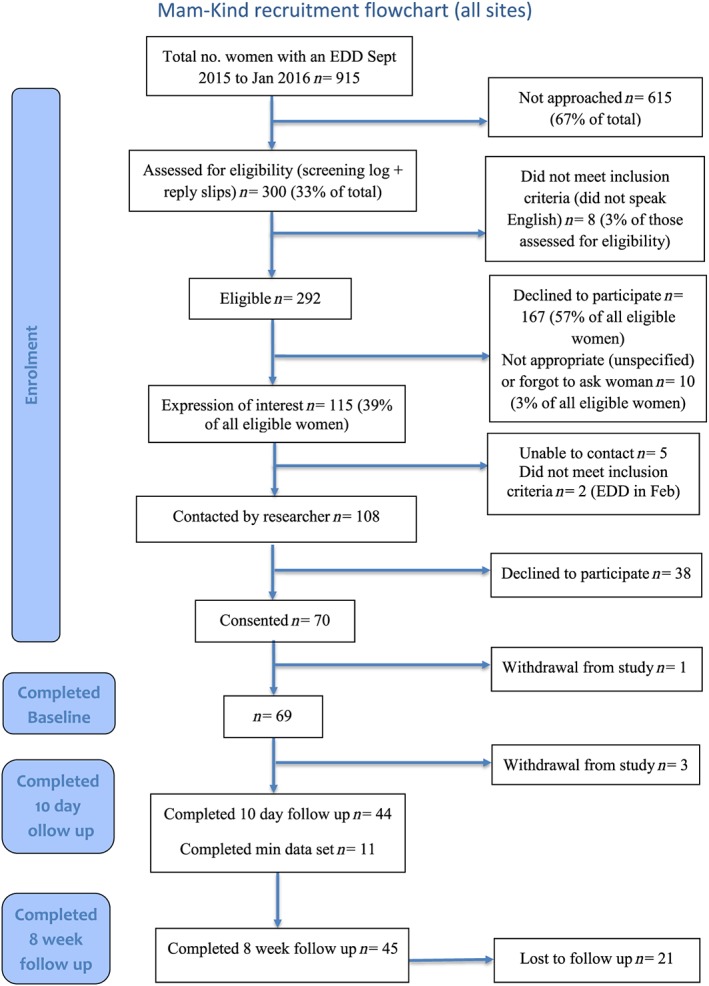

Of the 292 mothers who were assessed and met the eligibility criteria for the study, 39% (n = 115) expressed an interest in taking part (Figure 1). The expressions of interested that were collected by the introducing community midwives ranged from 1 to 18. The majority of mothers (94%, n = 108) who expressed an interest were successfully contacted by the study team. Of those contacted by the study team, 35% (n = 38) declined to participate. Seventy‐eight out of the 149 (52%) face‐to‐face peer‐support sessions were audio‐recorded (range 3–26 sessions per peer‐supporter), and a sample of 21 were used in the analysis on the basis of purposive sampling. The variation in number of audio‐recorded sessions per peer‐supporter was due to a combination of factors. Some peer‐supporters felt less comfortable about recording their sessions, in some cases the circumstances meant it was inappropriate for the session to be recorded or there were time constraints that made a recording less feasible.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flow diagram

3.2. Peer‐supporter recruitment

We recruited seven peer‐supporters who had previously successfully completed accredited BFPS training, and one peer‐supporter was new to the role who was provided with BFPS training as part of the study. Five of the eight peer‐supports lived in the geographical area in which they were supporting participants, two lived within a 10‐mile radius, and one lived approximately 20 miles away. The peer‐supporters ranged in age from 30 to 44 years and were all of White British origin.

3.3. Follow‐up data collection

Baseline data were collected for 99% of participants (n = 69). Data collection at 10 days follow‐up by telephone was successful for 63% (n = 44) of participants. Sixty‐four percent of participants (n = 45) completed the 8–10 week telephone follow‐up. The interviews indicated that overall, telephone data collection at 10 days postnatal was acceptable to participants, although some who had a longer stay in hospital or a difficult birth expressed that 10 days felt too early to be contacted. At 8 weeks, 51.1% of participants followed up were breastfeeding, with 42.2% exclusively breastfeeding.

3.4. Uptake of the Mam‐Kind intervention

All mothers were offered an antenatal contact with their peer‐supporter (face to face or by telephone). The offer of antenatal contact was accepted by 66% (n = 35) of primiparous and 72% (n = 18) of multiparous mothers. The majority of mothers engaged with the intervention: 67% (n = 35) of primiparous, and 68% (n = 17) of multiparous mothers accepted at least one antenatal and one postnatal contact. Mothers who engaged with the intervention reciprocated contact from peer‐supporters either by texting back, answering the telephone call, or meeting the peer‐supporter face to face.

3.5. Contact within 48 hr of birth

Seventy‐three percent of mothers (n = 51) received a contact within 48 hr of birth. Peer‐supporters reported that the main reason for not achieving any form of contact within 48 hr of birth was a lack of notification of the baby's birth by either the mother or the midwife. The main reason for limited face‐to‐face contact at hospital sites was that it was not possible for peer‐supporters to acquire the required approval to work on NHS sites within the time available for this study. Any delay could potentially have a detrimental effect on mothers' subsequent engagement with their peer‐supporter and motivation to continue with breastfeeding:

I had the sticker on the front of the folder, but nobody (from the hospital) had actually rung (the peer‐supporter). And then it was, I think it was two, two or three days after he'd been born, because I just completely forget really to be honest. Yeah, so then she didn't really get a chance to come up, but then we'd switched over (onto infant formula) in the hospital. [Mother, PID 201]

Peer‐supporters suggested that they could have visited the wards to introduce themselves to the staff, engage with mothers, and increase awareness of the intervention. In Site 3, mothers received peer‐support on the ward from a different peer‐support service as this was the usual care available in that site and were transferred to the care of the Mam‐Kind peer‐supporter when they returned home.

3.6. Mode and timing of contact

Data from the peer‐supporter diaries demonstrated that the majority of contacts in Sites 1 (n = 216, 52%) and 2 (n = 373, 73%) were made via mobile phone text message. In Site 3, the majority of contacts were made via phone call (n = 144, 68%; see Table 2). Mothers reported the text message contacts were especially helpful as they could express their feelings at a time appropriate for them in the knowledge that a peer‐supporter would reply to them as soon as they could.

Table 2.

Method and location of contacts between Mam‐Kind buddies and participating mothers

| Feature of contacts | Site 1 (n = 414) | Site 2 (n = 511) | Site 3 (n = 212)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Time of day | 00:00–08:59 | 25 (6.6) | 18 (3.7) | 0 |

| 09:00–16:59 | 219 (57.9) | 373 (76.4) | 93 (98.9) | |

| 17:00–23:59 | 134 (35.4) | 97 (19.9) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Missing data | 36 (8.7) | 23 (4.5) | 118b (55.7) | |

| Type of contact | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Breastfeeding group | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | |

| One‐to‐one face‐to‐face | 61 (14.7) | 55 (10.8) | 33 (15.6) | |

| 65 (15.7) | 0 | 0 | ||

| No contact | 4 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | |

| Phone | 61 (14.7) | 69 (13.5) | 144 (67.9) | |

| Text | 216 (52.2) | 373 (73.0) | 33 (15.6) | |

| Missing data | 6 (1.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Location of all face‐to‐face contact | Breastfeeding group | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) |

| Coffee shop | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Hospital | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | |

| Home | 40 (9.7) | 42 (8.2) | 27 (12.7) | |

| N/A (i.e., all contact made by phone or social media) | 362 (87.4) | 458 (89.6) | 181 (85.4) | |

| Missing data | 3 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Who initiated contact | Family/friend | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Health professional | 5 (1.2) | 26 (5.1) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Peer‐supporter | 294 (71.0) | 332 (65.0) | 181 (85.4) | |

| Mum | 107 (25.8) | 131 (25.6) | 18 (8.5) | |

| Missing data | 7 (1.7) | 22 (4.3) | 10 (4.7) |

Fewer contacts due to incomplete data entry at Site 3.

Missing data due to incomplete data entry at Site 3.

M: “I was able to do that, and even writing it down saying ‘This is what I'm struggling with.’ Makes a big difference with how you're coping with it.” [Mother, PID109]

The majority of contacts averaged across all sites were initiated by the peer‐supporters (n = 269, 74% of contacts), consistent with the requirement for proactive contact in the Mam‐Kind specification. During the interviews, health professionals reported that they received positive feedback from mothers about the amount of contact, although some of the mothers expressed that the proactive contact was too intense for them.

One of the other mums had said it was too much … whereas another mum loved it, and just lapped it up, she could have been visited 100 times and would have enjoyed it. [Health professional 001]

3.7. Quality and content of contact

During the interviews, mothers reported that the antenatal contact helped them to feel comfortable with their peer‐supporter, discussing personal and sensitive information, and facilitating the peer‐supporter‐mother relationship.

I think, you see beforehand I would have thought, oh, no it would have been better to have a few meetings to get to know her before I could start giving her personal information and looking to her for support, … .., but one meeting before the baby came it all seemed to work perfectly. [Mother PID 102]

During the postnatal period, mothers reported that the peer‐supporters provided guidance and signposting to appropriate forms of support on problems such as thrush on the nipple, mastitis, or colic.

When I had thrush it was such a nightmare and one day I even phoned her like half past 6 in the evening she was there to help me, you know she was always there. [Mother, PID 103]

Participants stated that the peer‐supporters preempted problems they thought mothers might develop on the basis of what the mothers were telling them, for example, strategies around cluster feeding or feeding in public. Some of the mothers reported feeling listened to, and that the peer‐supporter helped them to think about their breastfeeding options.

And when you think that somebody can validate your feelings almost, it was like, well I, I didn't feel happy and I wasn't comfortable, but somebody saying “No actually, you're allowed to feel like this.” [Mother, PID 109]

Participants reported that the peer‐supporters helped to build their confidence, provided reassurance and emotional support.

3.8. Adherence to intervention content

Content analysis was conducted for 21 peer‐support sessions. Findings are presented in Table 3, in which column headings indicate prespecified objectives from the intervention content guide, organised by time point.

Overall, peer‐supporters met 109 out of 117 total objectives. Ten of the 21 sessions met all objectives and included breastfeeding support that was relevant to the stage of the intervention. Eight sessions did not cover one of the objectives, and five included breastfeeding information that was beyond the scope of the session (time‐inappropriate).

3.9. MI skills adherence

Sixteen recordings from eight peer‐supporters were rated to assess how peer‐supporters were able to integrate MI in their conversations about breastfeeding maintenance (see Appendix S1 for intercoder reliability). For the technical global measures, we found a median 2.5 (range 2–4, interquartile range [IQR] 2.4–3.5) on a 5‐point scale. Peer‐supporters achieved higher scores for the softening sustain talk global measure and lower scores for the cultivating change talk global measure. Within the relational global scores, we found a median of 3.0 (range 1–4, IQR 1.5–3.5). Peer‐supporters generally had lower partnership scores compared with empathy scores.

The median ratio of reflective listening statements to questions was 1.2:1 median (range 0:1–3.5:1, IQR 0.5:1–2.25:1). Of the reflective listening statements used, a median of 37% (range 0%–75%, IQR 17%–60%) were complex compared with simple. All the peer‐supporters demonstrated both MI adherent (behaviours consistent with MI practice) and nonadherent behaviours (behaviours not consistent with MI practice).

The peer‐supporters reported that they found it challenging to use MI in the context of breastfeeding.

Sometimes it felt a little bit uncomfortable, the way sometimes I think MI is worded because we're not proficient at it yet ... I felt a little bit of a pressure on us to use it ... instead of trying to focus on what the mum was saying, it's quite hard to explain really. [PS1 01]

Peer‐supporters felt they needed practice to increase proficiency. They also found the concept of focusing on talk about change (change talk) difficult for them, as they felt conflicted in their role and did not want the participants to perceive them as having a feeding preference.

Because then we also were supposed to be supporting people if they're bottle‐feeding, so … and also just empowering mums. And if we're empowering mums, the change talk might be that they do decide to bottle‐feed, and that they become happier … So in terms of the training and clarity of what was … what are we listening for, you know … [PS1 02]

The peer‐supporters reflected that they wanted to help fix the participant's issues by giving them information. If a participant needed practical help with breastfeeding the peer‐supporters struggled to use MI skills taught to them to provide information or advice in a MI adherent manner.

The main problem with breastfeeding mums is the latch, getting the positioning right and once that's right, the feeding tends to flow. But with that it's less MI because you need to fix it really and give the information. [PS2 03]

Although the peer‐supporters did struggle with elements of MI they did express it was beneficial to their practice.

And I think it was, you know … beneficial then to … to … to the way we came across. [PS 2 02]

3.10. Concluding the Mam‐Kind intervention

Two weeks after birth, peer‐supporters were asked to facilitate the transition of support to other community support services such as breastfeeding groups. Some mothers felt they did not receive a graded exit from the intervention, whereas others did.

Well I don't know, maybe it could be phased out a bit more. Erm, maybe you know not full on support, but just you know have a conversation... [Mother, PID 102]

And by six weeks, you've figured that (breastfeeding latch and routine) out. I think it's er, it's a sensible time to do it, any sooner and you're still a bit lost in the haze. [Mother, PID109]

Some mothers felt supported by their peer‐supporter in attending groups and described this experience as helping them to normalise breastfeeding and also provided some structure to their day.

And I think it was a good place to start feeding in public there because everybody else was feeding as well … So it was nice to see other mums feeding and then you wasn't as anxious to do it yourself. [Mother, PID 315]

In some cases, the peer‐supporter supported mothers for longer than 6 weeks, with some mothers reporting that they received contact from their peer‐supporter at 8 weeks and 15 weeks. This was also reflected in the peer‐supporters' Mam‐Kind diary data.

4. DISCUSSION

This study established that it is possible to deliver most of Mam‐Kind as per the intervention specification, with good levels of intervention uptake and high acceptability to participating mothers. There were some challenges around achieving contact between mothers and peer‐supporters at 48‐hr postbirth, and improvement in the systems for notifying peer‐supporters of birth and enabling contact on the post‐natal wards need to be investigated.

Peer‐supporters demonstrated the use of a range of MI adherent behaviours, but also used nonadherent behaviours. Refinement of the training is required to ensure that they are given sufficient support in developing their person‐centred communication skills.

Wide variation in uptake and adherence have been reported in previous RCTs of BFPS interventions, with some describing low uptake and adherence (Muirhead et al., 2006; Watt et al., 2009). Other studies have reported more success with uptake and adherence (Graffy et al., 2004; Jolly, Ingram, Freemantle, et al., 2012), with antenatal contact rates of 80% and postnatal contact rates of 62%. Despite the challenges reported in a number of other studies, our results demonstrate that uptake and engagement with Mam‐Kind was high, with 75% of participants having received and reciprocated antenatal and postnatal contacts.

The majority of mothers were contacted by their Mam‐Kind peer‐supporter within 48 hr of the birth of their baby. Birth notification is an issue identified in this study and other studies (Hoddinott, Craig, Maclennan, Boyers, & Vale, 2012; McInnes & Chambers, 2008). By employing peer‐supporters through the existing health services, this would allow them access to postnatal wards and potentially allows a peer‐supporter to be available 7 days a week on the ward. This would provide participants with support within 24 hr of birth similar to other interventions (Hoddinott et al., 2012); however, there would be cost implications attached to this availability.

The average number of contacts each mother received in the current study was 16, the majority of which were by text (n = 207, 64%), although a range of other methods were used. Our qualitative interviews showed that the flexibility in method of contact was valued by mothers and was feasible for peer‐supporters to provide. The peer‐supporters, consistent with the requirement for proactive contact, initiated the majority of contacts. The content analysis demonstrated that prespecified objectives were met in most peer‐support antenatal and postnatal sessions. However, provision of a graded exit from the intervention to help participant's transition to autonomy or to the use of other sources of support (e.g., breastfeeding groups) could be improved.

MI informed the Mam‐Kind intervention, and our fidelity assessment suggests variability among peer‐supporters in their ability to develop MI skills. About a third of peer‐supporters evidenced an ability to listen, affirm, seek collaboration, emphasise autonomy, and avoid confrontation. However, there was also evidence of peer‐supporters trying to persuade mothers (MI nonadherent behaviour) to breastfeed by offering opinions or advice without explicitly reinforcing participants' autonomy. These results are similar to other studies that have assessed MI skills adherence using the MITI (Bennett, Roberts, Vaughan, Gibbins, & Rouse, 2007; Mounsey, Bovbjerg, White, & Gazewood, 2006; Tollison et al., 2008), including one peer‐support study (Tollison et al., 2008). In these studies, practitioners demonstrated higher levels of skill in relational competencies, such as empathy and collaboration, than the peer‐supporters in the Mam‐Kind study achieved. However, peer‐supporters in the Mam‐Kind study demonstrated higher reflections to questions ratios than in previous studies (Mounsey et al., 2006; Tollison et al., 2008).

We noted two key challenges related to the integration of MI in our intervention. First, peer‐supporters provided information in a way that was often not MI‐adherent, that is, without supporting mother's autonomy and choice and without tailoring the information to the mother's knowledge and need. Peer‐supporters developed breastfeeding expertise during training and were enthusiastic to share this in their sessions. They also, at times, shared their own success stories rather than understanding the needs, goals, and motivations of the mother (Allicock et al., 2013). Disclosing personal details has been suggested as part of the peer‐supporter's approach, which can inspire trust, dispel stigma, and instill hope (Oh, 2015). Self‐disclosure can be consistent with MI, where people have asked for this or permission to share a reflection has been sought by the person providing MI, but peers rarely self‐disclose in a manner that is consistent with MI (Oh, 2015). A second challenge we noted was in the peer‐supporter's ability to ensure the conversation stayed focused on breastfeeding. In some interactions, there were many tangential issues that were discussed with long periods of discussion that were not focused on breastfeeding. Focusing is an important phase of MI as it identifies the direction of the conversation in order to cultivate change talk (Miller & Rollnick, 2012a, 2012b). This challenge has been echoed in other research, which has found that it is difficult for practitioners to focus on one risk factor in “hard‐to‐reach” populations as their clients may have multiple needs (Velasquez et al., 2000). It is self‐evident that, in order to support mothers regarding breastfeeding maintenance, the conversational focus should be on breastfeeding for a significant period of time in order to make progress. These observations reflect underlying challenges with the professionalisation of the peer‐supporter role and have also led to redesign of key aspects of the Mam‐Kind intervention.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study included a comprehensive process evaluation of the Mam‐Kind intervention using data from qualitative interviews, diaries and audio‐recording of intervention delivery, and quantitative data. The combination of data has allowed for a greater understanding of MI and intensive peer‐support within the context of breastfeeding as we reliably measured MI fidelity. However, there are some limitations. We only interviewed one woman who disengaged with the intervention resulting in a positive bias in our assessment of acceptability. The recruitment of eligible mothers to the study was lower than anticipated, follow‐up at 8 weeks was lower than expected, and these issues would need to be addressed in any further study evaluating the effectiveness of the Mam‐Kind intervention. In terms of the content analysis, the majority of contacts the peer‐supporter had with the participants were via phone or text; therefore, the content that was coded as missing may have been provided to the mother via another medium other than face to face.

4.2. Recommendations for refinement of the Mam‐Kind intervention

These findings have informed our plans for future research. Given that a proportion of trainees are more receptive to developing MI skills (Berg‐Smith, 2014), recruitment of peer‐supporters could include an empathy prescreen to aid candidate selection. Cognitive empathy has been found to account for variance in treatment outcome thought to be of a clinically meaningful effect (Moyers & Miller, 2013). Although it is possible to observe empathic listening during an interview, there is no reliable measure to assess this (Moyers & Miller, 2013). The peer‐supporter role description could be reframed to allow the peer‐supporter to measure their success on the basis of collaboration rather than information giving. The tension between this role and system drivers (e.g., the belief that more knowledge alone is the key to maintaining breastfeeding) for information provision would need to be addressed during training and supervision.

In order to aid MI integration, sessions at each of intervention time point (antenatal, postnatal, and ending session) can be structured to facilitate focus and use of skill. This process may help to negate the usage of the MI nonadherent behaviours that can be harmful to a motivational interview (Magill et al., 2014), as manualised MI interventions have rare occurrences of MI‐non adherent behaviours (Magill et al., 2014). However, it has also been hypothesised that using a manual may lead to some practitioners to approach talking about behaviour change plans before the client is ready, leading to client resistance and poorer outcomes (Miller & Rollnick, 2004). The structure of the sessions must take this into account, allowing the peer‐supporter to be flexible, to work with the mother at her pace, in terms of thinking about behaviour change.

5. CONCLUSION

We have tested and established the feasibility of delivering the Mam‐Kind intervention with high uptake of the intervention within those that took part in the study. The mothers who were not lost to follow‐up and engaged reported that it was acceptable and found that the peer‐supporters provided them with guidance and reassurance. The combination of quantitative and qualitative results have highlighted key areas for improvement in recruitment, training, and supervision of those delivering MI within a public health intervention. Currently, there is a lack of high‐quality U.K.‐based evidence of effective peer‐support interventions for breastfeeding maintenance. Future research needs to test the effectiveness of a refined version of the Mam‐Kind intervention in a randomised controlled trial.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Billie Hunter's post is part‐funded by the Royal College of Midwives.

CONTRIBUTIONS

LC produced the first draft of this manuscript; all other coauthors have read and commented on subsequent drafts and have approved the final version submitted. SP (principal investigator), AG, JS, ST, MR, RPh, AB, DF, and BH developed the initial idea and design of this research. AG designed and oversaw the qualitative work packages. LC and LM conducted and analysed the qualitative interview data. RPh designed the intervention using the behaviour change wheel. CM analysed the session content data. LC and SC conducted the MITI 4.2 analysis. RPl conducted the statistical analysis. NG provided expertise on integrating the Motivational Interviewing approach in to the development process. JS, ST, and AB provided expertise on the clinical aspects of the intervention.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Professor Stephen Rollnick for his contribution to the development, delivery of MI training, and the integration of MI to the intervention. We would also like to thank the members of the Stakeholder Advisory Group for their contribution in providing their thoughts and feedback to the study team: Joanna Lourenco, Avril Jones, and Nicki Symes. We would also like to acknowledge Mary Whitmore for her contribution to the Study Management Group and site set up. We would like to thank Sam Clarkson for designing the database. We would like to thank Sue Channon and Helen Stanton for independently coding data. We would also like to thank all the administrative staff who worked on the study, within the South East Wales Trials Unit for their hard work and support. Finally, we would like to thank the participants and their families, the peer‐supporters, and the health professionals who kindly took the time to participate in the study.

Copeland L, Merrett L, McQuire C, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a motivational interviewing breastfeeding peer support intervention. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12703 10.1111/mcn.12703

REFERENCES

- Abeypala, U. , Chalmers, L. , & Trute, M. (2014). OP47 CONNECT2: A motivitional peer support model for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 106, S24–S25. 10.1016/S0168-8227(14)70253-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allicock, M. , Haynes‐Maslow, L. , Carr, C. , Orr, M. , Kahwati, L. C. , Weiner, B. J. , & Kinsinger, L. (2013). Peer reviewed: Training veterans to provide peer support in a weight‐management program: Move! Preventing Chronic Disease, 10 10.5888/pcd10.130084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G. A. , Roberts, H. A. , Vaughan, T. E. , Gibbins, J. A. , & Rouse, L. (2007). Evaluating a method of assessing competence in motivational interviewing: A study using simulated patients in the United Kingdom. Addictive Behaviors, 32(1), 69–79. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg‐Smith, S. M. (2014). The art of teaching motivational interviewing. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. , Phillips, R. , Copeland, L. , Grant, A. , Sanders, J. , Gobat, N. , … Paranjothy, S. (2018). Development of a novel motivational interviewing (MI) informed peer‐support intervention to support mothers to breastfeed for longer. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1). 10.1186/s12884-018-1725-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V. , & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1947–1952): Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P. , Dieppe, P. , Macintyre, S. , Michie, S. , Nazareth, I. , & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffy, J. , Taylor, J. , Williams, A. , & Eldridge, S. (2004). Randomised controlled trial of support from volunteer counsellors for mothers considering breast feeding. British Medical Journal, 328(7430), 26–29. 10.1136/bmj.328.7430.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler, M. , Halasyamani, L. , Resnicow, K. , Neaton, M. , Shanahan, J. , Brown, S. , & Piette, J. D. (2007). “I am not alone”: The feasibility and acceptability of interactive voice response‐facilitated telephone peer support among older adults with heart failure. Congestive Heart Failure, 13(3), 149–157. 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.06412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, P. , Craig, L. , Maclennan, G. , Boyers, D. , & Vale, L. (2012). The FEeding Support Team (FEST) randomised, controlled feasibility trial of proactive and reactive telephone support for breastfeeding women living in disadvantaged areas. BMJ Open, 2(2), e000652 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, K. , Ingram, L. , Freemantle, N. , Khan, K. , Chambers, J. , Hamburger, R. , … MacArthur, C. (2012). Effect of a peer support service on breast‐feeding continuation in the UK: A randomised controlled trial. Midwifery, 28(6), 740–745. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, K. , Ingram, L. , Khan, K. S. , Deeks, J. J. , Freemantle, N. , & MacArthur, C. (2012). Systematic review of peer support for breastfeeding continuation: Metaregression analysis of the effect of setting, intensity, and timing. British Medical Journal, 344, d8287 10.1136/bmj.d8287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, L. , Johnson, L.‐S. , Carr, C. , Alick, C. , & Mindy Gellin RNC, B. (2012). The use of motivational interviewing to promote peer‐to‐peer support for cancer survivors. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(5), E156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill, M. , Gaume, J. , Apodaca, T. R. , Walthers, J. , Mastroleo, N. R. , Borsari, B. , & Longabaugh, R. (2014). The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta‐analysis of MI's key causal model American Psychological Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, R. J. , & Chambers, J. A. (2008). Supporting breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(4), 407–427. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, R. J. , Love, J. G. , & Stone, D. H. (2000). Evaluation of a community‐based intervention to increase breastfeeding prevalence. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 22(2), 138–145. 10.1093/pubmed/22.2.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , Atkins, L. , & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. R. , & Rollnick, S. (2004). Talking oneself into change: Motivational interviewing, stages of change, and therapeutic process. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 18(4), 299–308. 10.1891/jcop.18.4.299.64003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. R. , & Rollnick, S. (2012a). Glossary of motivational interviewing terms updated July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. R. , & Rollnick, S. (2012b). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mounsey, A. L. , Bovbjerg, V. , White, L. , & Gazewood, J. (2006). Do students develop better motivational interviewing skills through role‐play with standardised patients or with student colleagues? Medical Education, 40(8), 775–780. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02533.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers, T. B. , & Miller, W. R. (2013). Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 878–884. 10.1037/a0030274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers, T. B. , Rowell, L. N. , Manuel, J. K. , Ernst, D. , & Houck, J. M. (2016). The motivational interviewing treatment integrity code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability, and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, P. E. , Butcher, G. , Rankin, J. , & Munley, A. (2006). The effect of a programme of organised and supervised peer support on the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: A randomised trial. British Journal of General Practice, 56(524), 191–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H. (2015). Peer‐administered motivational interviewing: Conceptualizing a new practice. Psychiatric Services, 66(5), 558–558. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S. , Pritchard, C. , & Szatkowski, L. (2016). The impact of breastfeeding peer support for mothers aged under 25: A time series analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(1), e12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison, S. J. , Lee, C. M. , Neighbors, C. , Neil, T. A. , Olson, N. D. , & Larimer, M. E. (2008). Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer‐led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavior Therapy, 39(2), 183–194. 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez, M. M. , Hecht, J. , Quinn, V. P. , Emmons, K. M. , DiClemente, C. C. , & Dolan‐Mullen, P. (2000). Application of motivational interviewing to prenatal smoking cessation: Training and implementation issues. Tobacco Control, 9(suppl 3), iii36–iii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. , França, G. V. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt, R. , Tull, K. , Hardy, R. , Wiggins, M. , Kelly, Y. , Molloy, B. , … McGlone, P. (2009). Effectiveness of a social support intervention on infant feeding practices: Randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(2), 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, S. L. , Flanders Stepans, M. B. , Hertzog, M. , Callahan Rodehorst, T. K. , & Gardner, P. (2006). Motivational interviewing to promote sustained breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 35(3), 340–348. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information