Abstract

Scaling up breastfeeding programmes has not been highly prioritized despite overwhelming evidence that breastfeeding benefits the health of mothers and children. Lack of evidence‐based tools for scaling up may deter countries from prioritizing breastfeeding. To fill this gap, Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) was developed to guide countries in effectively scaling up programmes to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. BBF includes an evidence‐based toolbox that consists of a BBF Index, case studies, and a 5‐meeting process. These three interrelated components enable countries to assess their breastfeeding scaling up environment, identify gaps, propose policy recommendations, develop a scaling up plan, and track progress. The toolbox was developed based on current evidence and expert guidance from a Technical Advisory Group, which was composed of global breastfeeding and metric experts with experience in the scaling up of health and nutrition programmes in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries. The BBF toolbox required a step‐by‐step iterative approach to describe and systematize each component, thus an operational manual was developed. The BBF toolbox and BBF operational manual underwent intensive pretesting in two countries, Ghana and Mexico, resulting in the modification of each component plus the operational manual. Pretesting continues in six additional countries demonstrating that BBF is a robust and dynamic multi‐sectoral process that, with relatively minor adaptations, can be successfully implemented in countries across world regions.

Keywords: breastfeeding, implementation science, metrics, nutrition, scale up, toolbox

Key messages.

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) is based on an evidence‐based, pragmatic process that enables countries to assess, analyse, and act on barriers for effective breastfeeding scaling up.

BBF involves a dynamic multi‐sectoral process that provides a toolbox for aiding policymakers in scaling up breastfeeding programmes within their countries.

The BBF toolbox provides countries with clear information about where they are, what they need, and how to scale up breastfeeding policies and programmes.

The multi‐sectoral nature of BBF promotes dialogue and effective problem‐solving among the many actors involved in breastfeeding that often lack the opportunity to “think together.”

1. INTRODUCTION

Strong evidence supports breastfeeding as a highly feasible and cost‐effective public health intervention to improve mothers' and children's short‐ and long‐term health outcomes (Britto et al., 2017; Rollins et al., 2016; Victora, Bahl, & Barros, 2016). However, no country has fully met the economic, environmental, social, and political recommendations for improving breastfeeding policies and programmes, and subsequently breastfeeding rates (United Nations Child Fund & World Health Organization, 2017b). Indeed, only 37% of infants under 6 months of age worldwide are exclusively breastfed whereas the prevalence of continued breastfeeding at 12–15 months continues to remain low (Victora et al., 2016).

Women are more likely to breastfeed in countries with a strong breastfeeding‐friendly environment, that is, where breastfeeding is protected, promoted, and supported (Rollins et al., 2016; Victora et al., 2016). However, countries have failed to invest financially and politically to support mothers to breastfeed (Lancet, 2017). A recent survey found that just 1 in 45 high‐level stakeholders in the world graded breastfeeding as a high political priority (United Nations Child Fund, 2013). Why is this so? Evidence suggests that lack of knowledge about the science of scaling up may deter countries from prioritizing the scaling up of breastfeeding interventions/programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016). Thus, there is a strong need for evidence‐based frameworks that guide and empower countries to prioritize breastfeeding on the national agenda and invest in scaling up of programmes embedded in breastfeeding‐friendly environments (Pérez‐Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016).

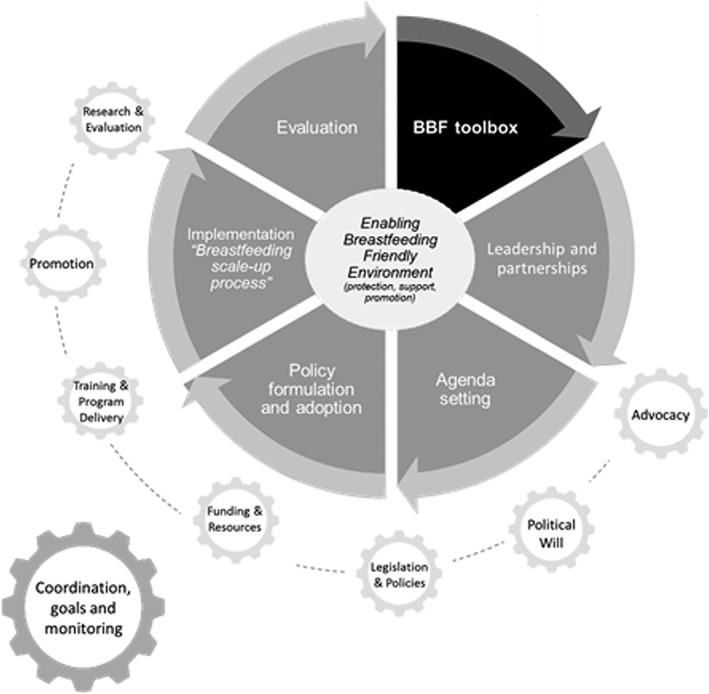

To fill this gap, the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) initiative was developed to guide countries in scaling up their national breastfeeding policies and programmes. BBF is grounded in the Breastfeeding Gear Model (BFGM), which takes a complex adaptive systems approach to evidence‐based scaling up of breastfeeding policies and programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla, Curry, Minhas, Taylor, & Bradley, 2012). The BFGM posits that eight gears—(a) Advocacy; (b) Political Will; (c) Legislation and Policies; (d) Funding and Resources; (e) Training and Program Delivery; (f) Promotion; (g) Research and Evaluation; and (h) Coordination, Goals, and Monitoring—must work in harmony to achieve large‐scale improvements in a country's national breastfeeding‐friendly environment to protect, promote, and support optimal breastfeeding practices (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012). To operationalize the BFGM into a useful resource for stakeholders and policymakers, BBF includes a toolbox to help countries assess, develop plans, and track breastfeeding scaling up in their specific contexts. The BBF toolbox has three main components: the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index (BBFI), case studies (CS), and a 5‐meeting process that culminates with the development of policy recommendations (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018).

BBF is designed to strengthen a country's process for scaling up their breastfeeding programmes in the context of breastfeeding‐friendly environments (Figure 1). BBF drives policy change and strengthens the breastfeeding friendly environment following the heuristic policy model, which includes: (a) leadership and partnerships; (b) agenda setting; (c) policy formulation and adoption; (d) implementation; and (e) evaluation (Darmstadt et al., 2014). BBF begins with engaging key stakeholders and identifying a country committee, which demonstrates a country's commitment to starting the process. Then, through the application of the BBF toolbox, countries assess their baseline status and track their progress in breastfeeding scaling up, identify gaps, and provide recommendations to strengthen breastfeeding scaling up efforts. At this point, partnerships have developed and leaders have emerged. Advocacy is essential to encourage leaders to drive the recommendations forward and subsequently generate the political will needed to set agendas and develop legislation that institutes policy changes. As policy is formed and adopted, provision of funding and investments in training and programme delivery, along with promotion efforts, contribute to implementation of the breastfeeding scaling up process. Research and evaluation identifies changes/improvements in breastfeeding practices that help countries determine when to reassess the scaling up environment via the BBF toolbox. Throughout, strong coordination continually strengthens the breastfeeding‐friendly environment.

Figure 1.

The role of the Breastfeeding Gear Model (BFGM) and Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) toolbox in enabling breastfeeding‐friendly environments

The aim of this manuscript is to (a) describe the development and operationalization of the BBF toolbox and (b) describe the stepwise iterative process of pretesting BBF through the application and testing of the BBF toolbox components in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries.

2. METHODS

2.1. Operationalizing BBF

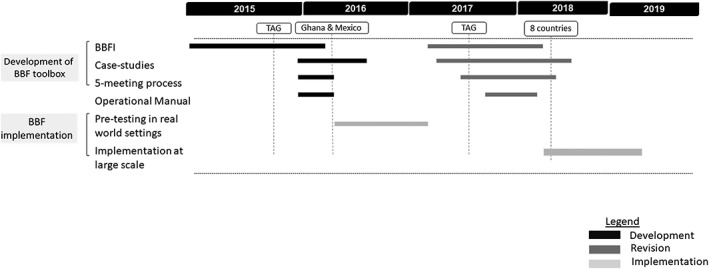

The BBF toolbox plus an operational manual were developed between March 2015 and September 2016 (Figure 2). Current scientific evidence and expert feedback from a Technical Advisory Group (TAG), which was composed of global breastfeeding and metric experts with experience in the scaling up of health and nutrition programmes, guided the development (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018). The three complementary components of the toolbox (i.e., BBFI, CS, and 5‐meeting process) are deemed critical to the goal of empowering countries to scale up their breastfeeding policies and programmes. First, the BBFI allows countries to assess their national readiness to scale up breastfeeding and, when reapplied, to track progress with such scaling up, through a multi‐sectoral committee. Second, CS provide stakeholders and policymakers with clear evidence‐based examples to guide the translation of policy and programme recommendations into action. Third, through a 5‐meeting process, countries use the BBFI and CS to develop and disseminate policy and programme recommendations, calling to action key multi‐sector stakeholders to collectively advocate for scaling up of breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018). The operational manual provides written guidance on how to implement BBF and apply the BBF toolbox. Together, the BBF toolbox and operational manual equips countries with a roadmap towards scaling up breastfeeding policies and programmes.

Figure 2.

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) toolbox, manual development, and pretesting timeline. BBFI: Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index; TAG: Technical Advisory Group

2.2. Development of BBF toolbox

2.2.1. Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index

The BBFI consists of 54 benchmarks measuring the eight gears of the BFGM. A complete description of the development of the BBFI is published elsewhere (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018). Briefly, systematic searches of the academic and grey literature on key metric projects that assessed country‐level readiness for scaling up health initiatives within the areas of infant and young child feeding, food and nutrition, and newborn survival were conducted to identify initial benchmarks that potentially assess the eight gears of the BFGM. The Delphi method was then used to determine the final benchmarks to include in the BBFI. The Delphi method is an iterative process that facilitates effective communication among a carefully selected panel of experts to reach consensus on a specified topic (Chia‐Chien Hsu, 2007; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Following the Delphi method, an online survey containing the initial benchmarks was distributed to the TAG for them to rank the importance and feasibility of each benchmark in representing a gear. A 3‐day in‐person meeting was then held, during which survey results were shared, discussions held, and another online survey was distributed to elicit consensus. A final survey was distributed a few months later to elicit final consensus on BBFI benchmarks. Using the benchmark rankings from the TAG meeting, scoring algorithms were developed to allow country committees to assess the strength of their national breastfeeding‐friendly environment within each of the gears as well as an overall country score.

2.2.2. Case studies

The CS are a rich and versatile package of real‐world examples of what countries have done to improve their breastfeeding‐friendly environments. The CS target two audiences: (a) country BBF committees and (b) policymakers involved with the BBF initiative. The CS help country committees to improve their understanding of the BBFI benchmarks, including how to score them, and develop specific recommendations to scale up breastfeeding. The CS also aim to guide policymakers on how to improve their breastfeeding‐friendly environment by illustrating how other countries have used data to implement legislation, policies, programmes, and trainings.

To identify potential CS, systematic searches of electronic databases (PubMed, SCOPUS, and Google Scholar) as well as conference proceedings, lectures, and websites (governments, non‐governmental organizations [NGOs], professional organizations, advocacy groups, and media) were conducted between December 2015 and July 2016. Combinations of keywords (i.e., breastfeeding; gear‐ and benchmark‐specific terminologies such as advocacy and legislation) were used to identify potential documents relevant for CS. Documents detailing potential CS were also identified by the Yale BBF team and TAG members. Documents in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were reviewed by the Yale BBF team, whereas those in other languages (i.e., German, Norwegian, Austrian, Vietnamese, and Filipino) were first translated by Google Translate to understand content and evaluate their potential contribution to CS. Those that looked promising were referred for further review and crosschecked. All documents were then evaluated and included if they (a) illustrated a real‐world example and (b) provided supporting evidence that reflected a benchmark/gear, described the use of data for decision making, or detailed the best practices or lessons learned relevant to breastfeeding. Those documents meeting the inclusion criteria were filed in EndNote by gear, and annotated bibliographies were generated to facilitate the collecting and classification of included documents into individual CS.

An iterative process was undertaken to ensure the relevance, accuracy, and quality of each CS. This involved an initial review of each CS by a Yale BBF team member, revisions, and then two additional reviews with subsequent revisions by the same team member as well as the Yale BBF principal investigator (R. P. E.). This process resulted in the development of 87 CS, classified into four broad categories: (a) clarified understanding of benchmark(s) description and scoring (n = 44); (b) data‐driven decision making (n = 3); (c) best practice or lessons learned from breastfeeding programmes (n = 14); or (d) combination of some or all of the three categories (n = 26).

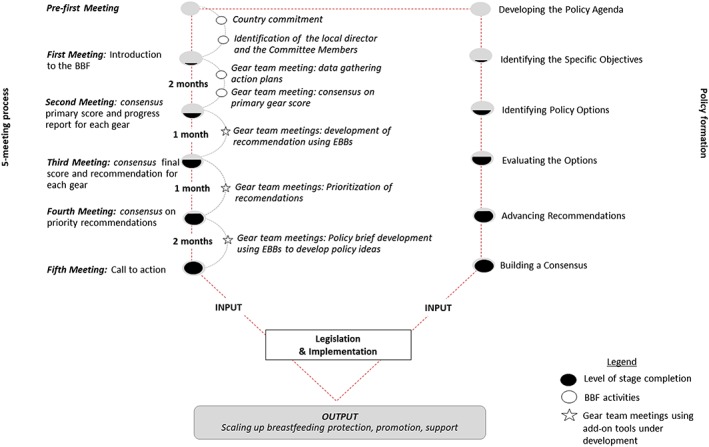

2.2.3. BBF 5‐meeting process

The 5‐meeting process was developed to reflect each of the steps taken towards policy formulation: developing a policy agenda (pre‐first meeting); identifying the specific objectives (first meeting); identifying the policy options (second meeting); evaluating the options (third meeting); advancing recommendations (fourth meeting); and building consensus (fifth meeting; Figure 3). Based on its proven effectiveness, the Delphi consensus strategy method was determined to be the best approach for the multi‐sectoral and interdisciplinary country committees to use to reach consensus (Chia‐Chien Hsu, 2007; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Thus, by following the Delphi method during each meeting, the country committee reaches consensus on the scoring of the BBFI as well as priority recommendations while taking into account the CS. This process is integral to the implementation of BBF and is described in further detail below.

Figure 3.

The stepwise dynamic process of implementing Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF). EBBs: evidence‐based briefs

2.3. BBF operational manual

The implementation of the BBF toolbox required a step‐by‐step approach to describe and systematize each component within an operational country‐level manual. The BBF toolbox required that each component be systematically applied according to its aim, purpose, and function. The BBF toolbox was operationalized within a 140‐page manual that detailed the BFGM framework, outlined the BBFI development, and described the 5‐meeting process. The BBF operational manual was developed over the course of 5 months (December 2015 to April 2016), and the majority of it was dedicated to describing the assessment and scoring of each of the 54 BBFI benchmarks. It included (a) a description of each benchmark, (b) potential data sources for scoring benchmarks, (c) a description of how to score each benchmark, and (d) the scoring interpretation. The majority of the benchmarks also had an accompanying CS to help clarify its description. The BBF operational manual was provided to all TAG members via email for their expert assessment during the preliminary development. It was revised based on two iterative rounds of consultation with TAG members, and a draft was finalized for implementation of BBF.

2.4. BBF implementation

BBF implementation is a stepwise, highly dynamic, and iterative multi‐sectoral process (Figure 3). Thus, support from key government, non‐governmental, and international agency actors is critical to the successful implementation of BBF. This support is needed to obtain access to the essential individuals and the data necessary to accurately apply the BBF toolbox and to engage in policy discussions throughout the process. Garnering support can occur through in‐person meetings with health and nutrition government actors as well as other influential, highly visible national, international agencies and NGOs. Identifying, sensitizing, and engaging these stakeholders, who can contribute to the scaling up of a breastfeeding‐friendly environment nationally, are essential for maximizing the utility of the BBF toolbox. Key stakeholders can also offer insights about whom to select as a country director to lead the implementation of BBF and the identification of potential country committee members.

Once a BBF country director is identified, this person is then instrumental in facilitating the selection of a 10‐ to 12‐member country committee. A country committee of experts serves as the foundation of BBF implementation. This committee dedicates their time and talent across approximately 9 months to apply the BBF toolbox, which includes reaching consensus on BBFI scoring and corresponding policy as well as programme recommendations on how best to scale up breastfeeding within their country. Therefore, it is important that the committee includes actors from government, civil society, NGOs, international agencies, lactation specialists, and academia. Thus, the country committee can be drawn from those key stakeholders that were identified while gaining initial country‐level commitment as well as government and non‐government sources. To be eligible to be a committee member, individuals must have the time to commit to applying the BBF toolbox (which includes attending all meetings and completing work in between meetings), have the ability to work in teams, and have expertise/extensive knowledge in one or more of the following areas: (a) breastfeeding policy; (b) breastfeeding training including health professional curriculum development and master trainers or lactation specialists; (c) delivery of breastfeeding education and services by health care professionals at the facility or community level; (d) breastfeeding promotion and behaviour change communication activities; (e) country‐level monitoring and evaluation systems (such as health information systems) that include breastfeeding indicators; (f) breastfeeding advocacy at the civil and government level; (g) funding and resources for breastfeeding directly or related activities; (h) national/regional/local coordination of breastfeeding activities and programmes; and (i) political will in the maternal, infant, and young child feeding arena.

Application of the BBF toolbox begins when the country committee convenes for the first meeting, which represents the start of the 5‐meeting process. The BBF country director leads and oversees the organization and coordination of the 5‐meeting process. At the first committee meeting, the country committee is introduced to the BBF vision and framework as well as the BBF toolbox. During this 2‐day meeting, a description of each of the 54 benchmarks of the BBFI is presented along with the data sources and scoring details. Within this same meeting, country committee members are divided into smaller groups according to their expertise (i.e., gear teams) and assigned to collect data as well as score their respective benchmarks.

The second meeting occurs 2 months later. By this time, gear teams are expected to have gathered, collected and analysed data, read the CS for each benchmark within their assigned gear(s), and reached primary consensus on benchmark scoring. By this point, gear teams may also have identified gaps in their national breastfeeding programmes/initiatives and discussed preliminary recommendations. Gear teams present their preliminary first round benchmark scores to the full country committee for discussion and consensus. If no consensus is reached or more data are needed to score individual benchmarks, gear teams gather after the second meeting to collect and discuss new findings, which are then presented at the third meeting.

During the third meeting, the benchmark scores along with any new data are presented for the country committee to reach the final consensus on all benchmark and gear scores. The committee also identifies gaps and uses the CS to develop recommendations to advance breastfeeding policy and programme scale up in the country.

The fourth meeting requires that the country committee reach consensus on the priority recommendations and propose action plans they feel will best address the critical gaps in their country's breastfeeding‐friendly environment. After the fourth meeting, key policymakers are invited to receive and respond to the priority recommendations that will be presented at the fifth meeting. At this time, the country committee also develops a policy brief that outlines the final gear scores, total overall BBF score, priority recommendations, and suggested actions. The CS can be used to guide the development of the policy brief as they provide solid examples illustrating how data have been used for breastfeeding decision making in other countries.

The fifth meeting is a call to action where the priority recommendations are disseminated to these policymakers and high‐level administrators, and discussions are held on how to act on these recommendations. The policy brief can serve as the primary dissemination tool in the fifth meeting to encourage policymakers and high‐level administrators to support breastfeeding policy, programmes, and promotion actions.

2.5. BBF pretesting in real‐world settings

BBF was implemented in Ghana (lower‐middle‐income country; The World Bank Group, 2018; Aryeetey et al., 2018) between June 2016 and February 2017 and Mexico (upper‐middle‐income country; The World Bank Group, 2018) between May 2016 and March 2017 (González de Cosío, Ferré, Mazariegos, & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2018). During this time, the BBF toolbox and operational manual underwent extensive testing. Both countries conducted the 5‐meeting process, assessed the BBFI, and utilized the CS during the 9‐month‐long testing period. The BBF country directors and project coordinators in Ghana and Mexico documented questions, feedback, and concerns that arose about the functionality and interpretation of the BBF toolbox and operational manual during BBF implementation. Six additional countries representing diverse income structures—high income (England, Scotland, Wales, and Germany), upper‐middle income (Samoa), and lower‐middle income (Myanmar)—and who are currently implementing the BBF toolbox, were also invited to submit questions, clarifications, and feedback following their extensive review of the BBF operational manual. All feedback was recorded.

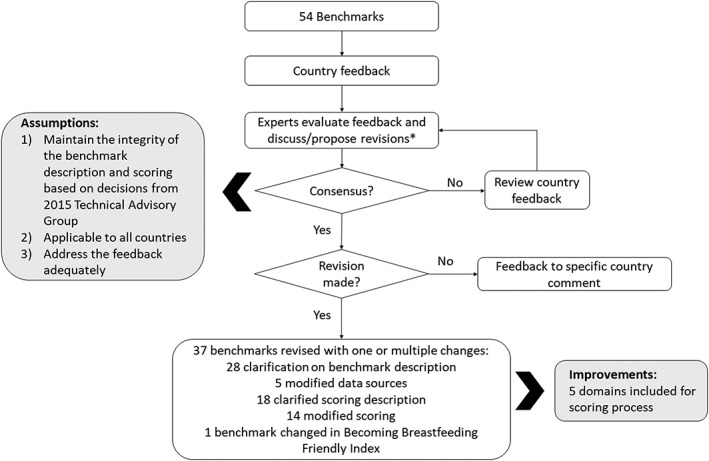

When issues or concerns arose, the Yale BBF team was consulted to reach resolution on any issues. Upon receipt of the feedback, Yale BBF team discussed and proposed solutions, reached consensus, then conveyed decisions to the countries (Figure 3). Once consensus was reached, it resulted in either modification in the manual and toolbox (described in Section 3), or if no changes were called for, further guidance or clarification to the countries was provided. All changes to the operational manual or toolbox followed these assumptions: (a) maintain the integrity of the benchmark description and scoring based on TAG decisions from their BBFI development meeting in 2015, (b) apply to all countries, and (c) address the feedback well.

3. RESULTS

3.1. BBF operational manual

Feedback was received for 49 of the 54 benchmarks related to applicability of benchmarks to the country's context; clarification of the benchmark description; wording; addition of data sources; and clarification of scoring instruction(s) (Figure 4). The consensus process undertaken by the Yale BBF team resulted in changes to the operational manual for 37 benchmarks with rationale provided for each (see Appendix A): changes/clarifications to benchmark descriptions (28 benchmarks); modifying data sources (five benchmarks); clarifying scoring description (18 benchmarks); and modifying scoring (14 benchmarks). No changes were made in the manual for the remaining benchmarks, but rather guidance was provided to countries on how to interpret them in their country context.

Figure 4.

Operational manual revision process

During testing, each benchmark was found to reflect multiple domains in their scoring process: (a) existence—the actual presence of implementation of a programme, legislation, policy, strategy, person, and so forth; (b) quality—the quality of implementation; (c) implementation fidelity/effectiveness—the adoption or level of incorporation; (d) coverage—the level of implementation (national, subnational, and local); and (e) volume/frequency—how much or how often. The domains within each benchmark were included in the manual to clarify the scoring process, and additional scoring pathway tools, which included these domains, were developed to facilitate straightforward benchmark scoring.

3.2. BBF toolbox

3.2.1. BBFI

Within the toolbox, feedback after the pretesting phase resulted in a change to one benchmark in the BBFI. The initial benchmark read, “More than 66.6% of hospitals and clinics offering maternity services have been designated or reassessed as “Baby Friendly” in the last 5 years.” This was changed to “More than 66.6% of deliveries take place in hospitals and maternity facilities designated or reassessed as ‘Baby Friendly’ in the last 5 years.” Although this change was the result of country feedback, it is also compatible with the new Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) implementation guidance (United Nations Child Fund & World Health Organization, 2018).

3.2.2. Case studies

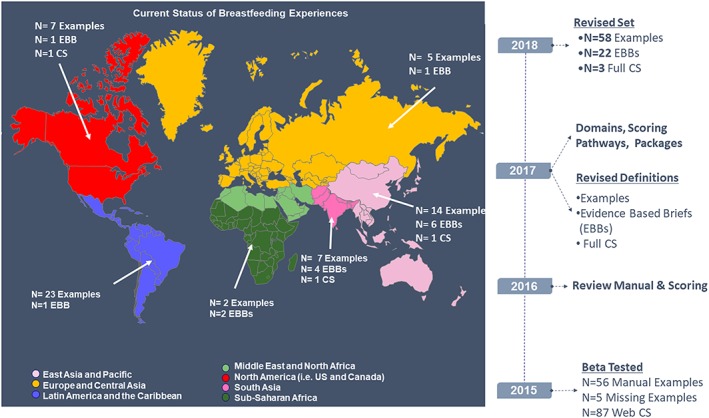

Based on the pretesting feedback related to benchmark interpretation, scoring, and use of the toolbox, the CS were also redesigned to improve their usefulness for the target audiences, that is, country committee members and policymakers. First, all the CS were reviewed to determine their applicability and suitability, which led to recategorizing them into well‐defined, structured categories consistent with their scope: illustrative examples of benchmark scoring, evidence‐based briefs (EBBs), and full CS (Figure 5). Examples are defined as small illustrations that help with understanding and scoring of the benchmarks. They are a resource for the BBF country director and committee to use and are found within the operational manual. EBBs are narrative pieces of a larger case study, typically related to an individual gear to provide evidence on how to implement BBF recommendation(s) building on the BBFI scores. EBBs are targeted to the country committee members as well as policymakers and are posted on the BBF website (http://www.bbf.yale.edu). Full CS are also found on the BBF website and target policymakers because they are a complex collection of EBBs focused on specific topics that illustrate how countries implemented legislation, policies, programmes, and trainings using data to drive decision making.

Figure 5.

Timeline of revisions of case studies categories and geographic representation of case studies (CS) globally

The 57 CS that were initially included in the operational manual were relabelled as examples. After being reviewed, 18 new examples were added, 17 examples were removed, 8 were revised, and 32 remained unchanged, resulting in 58 manual examples. Six of these new examples came from the BBF application in Mexico and two from Ghana. From the original 87 CS, 22 EBBS have been developed, with 20 more currently in development.

The CS review process also ensured that each of the 58 examples provided in the operational manual encapsulated the domains specific to each benchmark. Thus, each real‐world example was given a score (based on the benchmark scoring process) and the domains present in that example were highlighted as well. For four of the benchmarks, two examples were included to either better explain a technical nuance or illustrate the difference in level of scoring classification. The situation regarding the ratification of the International Labour Organization Maternity Protection Convention benchmark, in Brazil and Mexico are described to highlight the differences in progress each country has made. Brazil has not ratified the 2000 International Labour Organization Convention, but their Maternity Protection laws all meet or exceed the provisions, whereas Mexico has also not ratified the Convention and only has a few maternity protection laws that meet the provisions.

3.2.3. BBF 5‐meeting process

Both Ghana and Mexico followed the 5‐meeting process demonstrating that the Delphi method was successful, with committee members reaching consensus on benchmark scoring and recommendations over the 5‐meetings. Variations were seen between both countries in the length of time needed to score benchmarks; although Mexico reached final consensus on benchmark scoring in the third meeting, Ghana finalized their last scores after the fourth meeting. This difference in timing was likely due to between‐country differences in data availability. Additionally, as BBF did not provide detailed guidance at that time on how to prioritize recommendations, each country applied their own strategy. The Ghana BBF director led the prioritization efforts with input from the committee, reaching consensus on recommendations via email between the fourth and fifth meeting. The Mexico committee reached consensus during the fourth meeting.

Pretesting also suggested that the 5‐meeting process should be flexible based on country‐specific needs. Ghana elected to hold two meetings to disseminate findings and recommendations, one with technical staff from all key stakeholder organizations/institutions and a second with high‐level policymakers. An additional committee meeting was required in Mexico between the fourth and fifth meeting to prepare further for the call to action. This flexibility based on country‐specific need was added to the BBF manual.

The BBF directors in both countries were academic researchers from established public universities with expertise in breastfeeding and public health. This profile helped the process because it allowed for rigorous testing and documentation of the BBF implementation and application of the BBF toolbox.

In both countries, committee members were identified by the directors in close consultation with individuals working with a different mix of government, non‐governmental, and/or international organizations on breastfeeding issues resulting in slight differences in the multi‐sectoral composition of the country committees. In Ghana, committee members represented government, hospitals, and academic organizations; in Mexico, civil society organizations and lactation consultants were also represented.

Since the pretesting phase in Ghana and Mexico, BBF has now been launched in Germany, Myanmar, Samoa, England, Scotland, and Wales. The reassessment of BBF is also underway in Mexico and Ghana to track their progress. The improvements made to the BBF toolbox as a result of pretesting have been extensively tested through the training of the new BBF countries and the retraining of Mexico and Ghana BBF teams. Very few additional needed changes have been identified.

4. DISCUSSION

BBF includes a dynamic and iterative multi‐sectoral process that incorporates the use of a toolbox for aiding policymakers in scaling up integrated breastfeeding interventions within their country. The BBF pretesting experience indicates that it is meeting key conditions previously found to promote evidence‐informed policy decisions: establishing an imperative, building trust, developing a shared vision, and actions that translate research into action (Sarkies et al., 2017). Like other health and nutrition initiatives designed to help countries scale up efforts (Darmstadt et al., 2014; Moran et al., 2012), full country support and engagement from policymakers and key stakeholders across sectors, including civil society, is essential to implement BBF and to use it for effective decision making that eventually leads to sustainable breastfeeding scaling up. BBF generates dialogue within and beyond committee members on gaps, prioritized recommendations, and actions that are shared with policymakers. Commitment is strengthened through these actions, which countries are finding to be a fundamental strength of BBF.

Previous breastfeeding country‐level assessments (BPNI/IBFAN‐Asia, 2014; World Health Organization, 2003) have not provided comprehensive and illustrative non‐linear roadmaps to show countries how to effectively scale up breastfeeding. BBF empowers countries to identify and find their own solutions given their own country context. CS are a critical tool to introduce to policymakers because they provide countries with evidence‐based real‐world examples demonstrating how other countries used data to inform and influence breastfeeding decisions (Kitson, Harvey, & McCormack, 1998; Lavis, Posada, Haines, & Osei, 2004; The Council of State Governments, 2008). Data‐driven decision making is essential for empowering policymakers to make the right choices (Kitson et al., 1998; Lavis et al., 2004). BBF provides key tools to help policymakers compile and use their own data to make the best‐informed decisions about how to scale up breastfeeding within their country. Thus, policymakers can rely on the BBF toolbox to provide them with an evidence based process for scaling up integrated breastfeeding interventions that can contribute to improved breastfeeding outcomes and ensure the sustainability of their programmes. Additionally, the reapplication of BBF toolbox allows stakeholders and policymakers to continually evaluate their progress and review their priorities to breastfeeding scale up.

Operational manuals, such as the one developed for BBF, are needed for effective scale up in complex and dynamic environments (Perez‐Escamilla, Segura‐Perez, & Damio, 2014). The BBF toolbox integrates the BBFI, CS, and a 5‐meeting process into a standardized manual that provides clear guidelines to countries in how to assess their readiness to scale up breastfeeding based on evidence (Lavis et al., 2004). The toolbox, including its operational manual, has undergone rigorous testing to strengthen it and provide clarity for countries. The pretesting process resulted in documented changes to each of the toolbox components to improve their interpretation and utility for BBF. Pretesting confirmed the need for flexibility in BBF implementation so countries can adapt and interpret the BBF toolbox based on their context and differences (Lavis et al., 2004; Sarkies et al., 2017). Pretesting also identified the need for additional support tools to strengthen the 5‐meeting process that are currently under development, including a simple method to prioritize recommendations, policy brief templates, and guidance on how to use EBBs to make recommendations. Finally, although major changes are not expected given the findings of the highly iterative pretesting phase, the BBF toolbox and ancillary support tools will continue to be updated via the website to ensure that it continues to meet the needs of countries globally.

Through BBF, countries have the opportunity to enable their environment to effectively scale up their breastfeeding policies and programmes using an evidence‐based toolbox. Given these promising findings, BBF is expected to strongly facilitate the effective integration and coordination of breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support policies, programmes, and actions, across sectors, taking into account the unique social, political, and health care systems of each country (Pérez‐Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

CONTRIBUTIONS

RPE and AHF conceptualized the study, the BBF toolbox, and developed the 5‐meeting process. RPE, AHF, MBG, and GSB developed the BBFI and scoring. KD and GSB developed and revised case studies. RPE, AHF, GSB, and KD participated in BBF pretesting within Ghana, Mexico, and current countries. All authors contributed to the study design, analysis, and writing of the report. GSB and KD developed the manuscript figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank BBF‐Yale investigators for their participation in BBF and feedback on this manuscript: Kassandra Harding, Cara Safon, and Grace Carroll. The authors also wish to acknowledge the following TAG members for their contributions to BBF: Chessa Lutter, France Begin, Teresita Gonzalez de Cosio, Rukhsana Haider, Sonia Semenic, Marcia Griffiths, Neemat Hajeebhoy, Leslie Curry, Alison Tumilowicz, Ashley Fox, Richmond Aryeetey, Laurence Grummer‐Strawn, and Fiona Clare Dykes.

APPENDIX A.

| Benchmarks | Category of change | Change | Domains | Rationale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG1: There have been major events that have drawn media attention to breastfeeding issues. | Benchmark description | Major events include planned events to galvanize public attention towards advocating for breastfeeding. | Existence | Volume/frequency |

(a) BBF committees suggested using numbers of national events to rank. (b) BBF committees counted national events so level of coverage removed and only national events included; focus on number and “persistence” (i.e., range throughout year) of events. |

|

| Data sources | Consider including a table that documents both positive and negative media attention around a planned event and weigh whether it galvanized public attention towards advocating for breastfeeding. | |||||

| Scoring | Addition of the actual numbers of events drawing national media coverage to breastfeeding issues at different times during the year. | |||||

| AG2: There are high‐level advocates (i.e., “champions”) or influential individuals who have taken on breastfeeding as a cause that they are promoting. | Benchmark description | Addition of frequency: Champions are seen at least 3 times within the year promoting breastfeeding. Committee should consider the level of influence for each potential champion. | Existence | Volume/frequency | Definition clarified to standardize measurement. | |

| Data sources | Media surveys conducted by the committee or a commissioned agency can identify high‐level champions. | |||||

| AG3: There is a national advocacy strategy based on sound formative research. | Benchmark description | Clarification that a national advocacy strategy is a governmental or non‐governmental document or initiative that aims to organize and/or systematize breastfeeding advocacy actions within the country. | Existence | Quality | Effective | Definition clarified to standardize measurement. |

| Data sources | Annual reports from advocacy groups can be evaluated. | |||||

| Scoring description | Define effective as “operational” = strategy implemented AND generated support for breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support. | |||||

| AG4: A national cohesive network(s) of advocates exists to increase political and financial commitments to breastfeeding. | Benchmark description | (a) A network is formed by two or more advocate groups and is considered cohesive when they work collectively. (b) Network activity must be proportional to its coverage (national, subnational, and/or local). (c) Network needs to include breastfeeding advocacy as a key focus but not only advocacy issue it defends. | Existence | Coverage |

(a) Clarification requested about networks comprising organizations and not individuals. (b) Scoring differences meant clarification needed on focus of network. |

|

| Scoring | Addition of the word “national “to cohesive network(s). | |||||

| PWG1: High level political officials have publicly expressed their commitment to breastfeeding action. | Benchmark description |

(a) Public expression of commitment or promise by at least two government officials. (b) High level political officials can be within the federal and/or state government. |

Existence | Volume/frequency | Quality |

(a) Standradize scoring by specifying number of officials. (b) Commitment can come from different levels of government. (c) Countries choose how to score strength of commitment of officials at state/federal level. |

| Scoring description | To assess the difference between minimal and partial progress, the high level political officials must have publicly spoken about breastfeeding AND expressed their commitment to action. | |||||

| Scoring | Changed no progress from “no progress has been made if high level political officials have not publically expressed their commitment to breastfeeding action at all” to “no progress has been made if high level political officials have not spoken publically about breastfeeding nor publically expressed their commitment to breastfeeding action at all” to make sure that it reflects that no one has spoken about breastfeeding to be sure it is different form minimal progress.” | |||||

| Example | Changed example from Michelle Obama to another figure (TBD) because it may vary from country to country whether the first lady is considered a political official. | |||||

| PWG2: Government initiatives have been implemented to create an enabling environment that promotes breastfeeding. | Benchmark description |

(a) Government led initiatives can cross multiple sectors. (b) List of interventions/initiatives that create an enabling environment for breastfeeding. (c) Enabling interventions remove structural & societal barriers that interfere with optimal breastfeeding. |

Existence | Effective |

(a) Actions to change environment emanate from different areas. (b) Help to operationalize benchmark and better measure the impact of initiatives. |

|

| Scoring description |

Sets out specific steps: (a) Identify the specific barriers to improving breastfeeding practices. (b) Identify enabling initiatives that have been implemented. (c) Match those initiatives with how they have impacted the breastfeeding‐friendly environment. The scoring of this benchmark reflects the level of implementation and the quality of the enabling environment. |

|||||

| PWG3: An individual within the government has been especially influential in promoting, developing, or designing breastfeeding policy. | Benchmark description | Reflects existence and level of influence of a government individual or collective group of individuals. | Existence | Effective | Taking into account different governance structures. | |

| Scoring description | (a) Addition of the term “collective group of individuals.” (b) Advise mapping all the individuals who work on breastfeeding policy, then map the activities or the collective activities they have been working on towards on promoting, developing, or designing breastfeeding policy. | |||||

| LPG1: A national policy on breastfeeding has been officially adopted/approved by the government. | Benchmark description | (a) A policy is a “high level overall plan embracing the general goals and acceptable procedures of a governmental body.” (b) Existence of a policy does not necessarily mean funding or an implementation plan in place. | Existence | Effective | ||

| LPG2: There is a national breastfeeding plan of action. | Benchmark description | An action plan is a series of steps that need to be taken to implement the policy. The action plan should include step‐by‐step actions including targets and timeframes. | Existence | Quality | Implementation, evaluation, and monitoring should be included. | |

| Scoring | • Minimal progress: Some strategies in national breastfeeding plan of action implemented but the plan does not contain measurable nor time‐bound objectives/targets.• Partial progress: Some strategies in national breastfeeding plan of action implemented and the plan contains measurable and time‐bound objectives/targets. • Major progress: All strategies in national breastfeeding plan of action implemented and the plan does contain measurable and time‐bound objectives/targets. | |||||

| LPG3: The national BFHI/Ten Steps criteria has been adopted and incorporated within the health care system strategies/policy. | Scoring description | The difference between partial and major progress is reflected in the example of a country that has national BFHI/Ten Steps criteria, consistent with BFHI WHO/UNICEF global criteria and is adopted, but it has only been incorporated into the hospital strategies/policies nationally and not into the primary health network or community services strategies/policies. | Existence | Effective | Quality | |

| LPG4: The International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes has been adopted in legislation. | Benchmark description | Addition of an annex summarizing the main points of the Code. | Existence | Effective | Quality | |

| Scoring description | If a country modifies their Code to a lower standard than the International Code, they cannot receive a score of major progress. | |||||

| LPG5: The National Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes has been enforced. | Scoring description | Scoring reflects the degree and coverage of enforcement of the National Code. Penalties and sanctions must be considered only if they are proportional to the violation. | Coverage | To ensure sanctions are a disincentive. | ||

| LPG6: The International Labour Organization maternity protection convention has been ratified. | Scoring description | Benchmark assesses whether the Maternity Protection Convention 2000 (No. 183), put forth by the International Labour Organization (ILO), has been ratified or existing maternity protection legislation meets some or all of their provisions. It allows for other maternity laws but uses the standards expressed in the Maternity Protection Convention 2000 as the benchmark countries should strive to meet. | Existence | Coverage | Change takes into account countries with maternity protection laws that meet/exceed Maternity Protection Convention 2000 but it has not been ratified. | |

| Scoring |

• No progress: No maternity protection laws in the country and Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No 183) has not been ratified. • Minimal progress: A few maternity protection laws meet provisions of Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) but not ratified. • Partial progress: Most maternity protection laws meet provisions of Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) but not ratified. • Major progress: All maternity protection laws meet or exceed the provisions of Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) or is ratified. |

|||||

| LPG7: There is paid maternity leave legislation for women. | Existence | Quality | ||||

| LPG8: There is legislation that protects and supports breastfeeding/expressing breaks for lactating women at work. | Benchmark description | If a country committee feels that this legislation is not being effectively exercised or not enforced, it can be put forth as a recommendation for action. | Existence | Coverage | Captures effectiveness of legislation and allows committees to define “effective.” | |

| LPG9: There is legislation for supporting worksite accommodations for breastfeeding women. | Benchmark description | If a country committee feels that this legislation is not being effectively exercised or not enforced, it can be put forth as a recommendation for action. | Existence | Coverage | Captures effectiveness of legislation and allows committees to define “effective.” | |

| LPG10: There is legislation providing employment protection and prohibiting employment discrimination against pregnant and breastfeeding women. | Benchmark description | If a country committee feels that this legislation is not being effectively exercised or not enforced, it can be put forth as a recommendation for action. | Existence | Quality | Captures effectiveness of legislation and allows committees to define “effective.” | |

| FRG1: There is a national budget line(s) for breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support activities. | Existence | Quality | ||||

| FRG2: The budget is adequate for breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support activities. | Scoring | Addition to minimal and partial progress of the line “There is a national budget line(s) for breastfeeding protection, promotion and support activities or there is not a specific budget line but funding is provided for breastfeeding resources … ” | Existence | Quality | Allows for countries without specific budget line for breastfeeding but with other resources in place (e.g., staffing) that are invested in breastfeeding to account for those resources. | |

| Scoring | Addition to no progress of the line “There is no national budget line(s) for breastfeeding protection, promotion and support activities nor is funding provided for breastfeeding resources.” | |||||

| FRG3: There is at least one fully funded government position to primarily work on breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support at the national level. | Existence | Quality | ||||

| FRG4: There is a formal mechanism through which maternity entitlements are funded using public sector funds. | Existence | Coverage | ||||

| TPDG1: A review of health provider schools and pre‐service education programmes for health care professionals that will care for mothers, infants, and young children indicates that there are curricula that cover essential topics of breastfeeding. | Data sources | If no surveys exist, a survey of relevant university administrators can be administered to determine curricula content or the survey can be applied a representative sample of schools. | Existence | Coverage | Quality | Suggestion based on beta testing experiences. |

| TPDG2: Facility‐based health care professionals who care for mothers, infants, and young children are trained on the essential breastfeeding topics as well as their responsibilities under the Code implementation. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG3: Facility‐based health care professionals who care for mothers, infants, and young children receive hands‐on training in essential topics for counselling and support skills for breastfeeding. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG4: Community‐based health care professionals who care for mothers, infants, and young children are trained on the essential breastfeeding topics as well as their responsibilities under the Code implementation. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG5: Community‐based health care professionals who care for mothers, infants, and young children receive hands‐on training in essential topics for counselling and support skills for breastfeeding. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG6: Community health workers and volunteers that work with mothers, infants, and young children are trained on the essential breastfeeding topics as well as their responsibilities under the Code implementation. | Benchmark description | Volunteers are people who provide breastfeeding counselling and support but are not paid for providing that service. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |

| TPDG7: Community health workers and volunteers that work with mothers, infants, and young children receive hands‐on training in essential topics for counselling and support skills for breastfeeding. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG8: There exist national/subnational master trainers in breastfeeding (i.e., breastfeeding specialists or lactation consultants) who give support and training to facility‐based and community‐based health care professionals as well as community health workers. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Master trainers have received national or international certification as breastfeeding specialists or lactation consultants.” | Existence | Coverage |

(a) Clarify master trainer certification. (b) Allow for assessing coverage, if master trainers exist at national or state level—is coverage country‐wide? |

|

| Scoring | Addition to partial and major progress: “Master trainers in breastfeeding at the national and subnational level throughout the country.” | |||||

| TPDG9: Breastfeeding training programmes that are delivered by different entities through different modalities (e.g., face‐to‐face; on‐line learning) are coordinated. | (a) Clarify that benchmark is specific to breastfeeding training programmes.(b) Courses can be implemented by different entities; however, they should be integrated, registered, evaluated, and/or certified in order to be coordinated. | Existence | Coverage | Original wording not clear that breastfeeding training programmes implemented by different entities should be included. | ||

| TPDG10: Breastfeeding information and skills are integrated into related training programmes (e.g., maternal and child health, IMCI). | Benchmark description | Addition of Ten Steps; the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) as examples of related training programmes. | Existence | Coverage | ||

| Data sources | If documentation does not exist, surveys can be distributed to training programmes to assess training courses, manuals, and curricula to determine if breastfeeding information and skills are integrated into these programmes and the level of integration. | |||||

| TPDG11: National standards and guidelines for breastfeeding promotion and support have been developed and disseminated to all facilities and personnel providing maternity and newborn care. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Breastfeeding standards and guidelines can be developed and disseminated as an individual guideline or included in other maternity and/or child health materials (e.g., young child feeding guidelines, child health guidelines).” | Existence | Coverage | Beta testing found that some countries only considered those specific to breastfeeding but guidance may be incorporated into other maternal and/or child health information. | |

| TPDG12: Assessment systems are in place for designating BFHI/Ten Steps facilities. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG13: Reassessment systems are in place to re‐evaluate designated Baby‐Friendly/Ten Steps hospitals or maternity services to determine if they continue to adhere to the Baby‐Friendly/Ten Steps criteria. | Existence | Quality | ||||

| TPDG14: More than 66.6% of deliveries happen in facilities designated or reassessed as “Baby Friendly.” | Benchmark title | Previous wording: “More than 66.6% of hospitals and clinics offering maternity services have been designated or reassessed as ‘Baby Friendly’ in the last 5 years.” | Coverage |

(a) Assessing coverage of the deliveries to better measure BFHI coverage and compatible with the revised BFHI guidelines. (b) Impact of BFHI better assessed by coverage of deliveries in facilities versus BFHI designation. (c) Births in private facilities not captured in previous definition. |

||

| Benchmark description | It is important to understand if the per cent of public and private hospitals and maternity facilities designated or reassessed as Baby‐Friendly is increasing, decreasing, or remaining the same. | |||||

| Benchmark description |

The following questions from the WHO Global Nutrition Policy Review module on the Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative can be used to help assess how many health care facilities (public and private) have ever been designated Baby‐Friendly: • How many of these have been designated or reassessed as Baby‐Friendly in the past 5 years? • What is the total number of births per year in the facilities that were designated or reassessed as Baby‐Friendly in the past 5 years? |

|||||

| Scoring description | Scoring reflects the coverage of deliveries in BFHI designated or reassessed hospital and maternity facilities in a country. | |||||

| Scoring | Addition of number of deliveries taking place in hospitals and maternity facilities designated or reassessed as “Baby‐Friendly” in the last 5 years to minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| TPDG15: Health care facility‐based community outreach and support activities related to breastfeeding are being implemented. | Existence | Quality | Effective | |||

| TPDG16: Community‐based breastfeeding outreach and support activities have national coverage. | Scoring description | Addition: “Full national coverage refers to the fact that all activities are being implemented to cover all of the specific target population. For example, if a community based breastfeeding initiative is designed to reach an indigenous/ethnic population that only lives within a certain geographical area within the entire country, coverage would be considered national if the programme activities reach the entire target population.” | Existence | Coverage | Clarification of coverage needed regarding population specific or entire population programmes. | |

| Benchmark description | ||||||

| TPDG17: There are trained and certified lactation management specialists available to provide supportive supervision for breastfeeding programme delivery. | Scoring |

• Minimal progress: Subnational/local coverage changed to Local. • Partial progress: Partial national coverage changed to Subnational . |

Existence | Coverage | ||

| PG1: There is a national breastfeeding promotion strategy that is grounded in the country's context. | Benchmark description |

(a) Addition: “The national breastfeeding promotion strategy can include formal campaign(s) (including one or more) targeting specific or entire population. It can also include the relaying of messages through one or multiple channels including mass media campaigns, interpersonal communication, posters, educational materials, etc.” (b) Strategy must specify time frame. |

Existence | Quality | Quality |

(a) Definition of promotion strategy requested by beta testers. (b) Time frame missing from description but in scoring. |

| PG2: The national breastfeeding promotion strategy is implemented. | Benchmark description | Addition “… can include formal campaign(s) (including one or more) targeting specific or entire population. It can also include the relaying of messages through one or multiple channels including mass media campaigns, interpersonal communication, posters, educational materials, etc.” | Existence | Effective | Coverage |

(a) Definition of promotion strategy requested by beta testers. (b) Clarification of coverage needed. |

| Scoring description | Coverage can be national or full depending on goals of strategy National coverage = implemented to the entire population Full coverage = complete coverage of a subpopulation | |||||

| PG3: Government or civic organizations have raised awareness about breastfeeding. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Government and/or civic organizations' promotion campaigns, activities, or actions designed to raise awareness about breastfeeding should be considered under this benchmark.” | Coverage | Ensure assessments include any civil society involvement. | ||

| REG1: Indicators of key breastfeeding practices are routinely included in periodic national surveys. | Volume/frequency | |||||

| REG2: Key breastfeeding practices are monitored in routine health information systems. | Benchmark description | This benchmark assesses if key breastfeeding practices are monitored in routine health information systems, and gauges their coverage and if key indicators have been publicly reported. Clarification: full coverage = national, subnational, and local coverage | Existence | Coverage | Quality |

(a) Consistent with the other benchmarks evaluating monitoring systems. (b) Possible fragmentations within health care systems that affect national coverage. |

| Scoring description | Clarification: full coverage = national, subnational, and local coverage | |||||

| Scoring | Addition of “key indicators publicly reported” to minimal, partial, and major progress | |||||

| REG3: Data on key breastfeeding practices are available at national and subnational levels, including the local/municipal level. | Existence | Coverage | ||||

| REG4: Data on key breastfeeding practices are representative of vulnerable groups. | Existence | Coverage | ||||

| REG5: Indicators of key breastfeeding practices are placed in the public domain on a regular basis. | Benchmark description | Include more complete definition of “public domain”:Published reports, media coverage, public social media sites, and database(s) available to researchers & public. | Volume/frequency | To differentiate between publicly available information for those interested and specific efforts to make information available to the general public. | ||

| REG6: A monitoring system is in place to track implementation of the Code. | Scoring description | Addition of an operational element to scoring, i.e., the monitoring system should be used to track and enforce Code violations. | Existence | Effective | Need to include operational dimension to ensure properly functioning monitoring system. | |

| Scoring | Operational dimension added to scoring of minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| REG7: A monitoring system is in place to track enforcement of maternity protection legislation. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Monitoring systems systematically and routinely collect data on process indicators in order to track progress of programs or initiatives to ensure implementation and effectiveness.” | Existence | Effective | Need to include operational dimension to ensure properly functioning monitoring system. | |

| Scoring description | Addition of an operational element to scoring, i.e., the monitoring system should be used to track and enforce maternity protection legislation. | |||||

| Scoring | Operational dimension added to scoring of minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| REG8: A monitoring system is in place to track provision of lactation counselling/management and support. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Monitoring systems systematically and routinely collect data on process indicators in order to track progress of programs or initiatives to ensure implementation and effectiveness.” | Existence | Effective | Need to include operational dimension to ensure properly functioning monitoring system. | |

| Scoring description | Addition of an operational element to scoring, i.e., the monitoring system should be used to track the provision of lactation counselling/management and support. | |||||

| Scoring | Operational dimension added to scoring of minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| REG9: A monitoring system is in place to track implementation of the BFHI/Ten Steps. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Monitoring systems systematically and routinely collect data on process indicators in order to track progress of programs or initiatives to ensure implementation and effectiveness.” | Existence | Effective | Need to include operational dimension to ensure properly functioning monitoring system. | |

| Scoring description | Addition of an operational element to scoring, i.e., the monitoring system should be used to track the compliance of the BFHI/Ten Steps. | |||||

| Scoring | Operational dimension added to scoring of minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| REG10: A monitoring system is in place to track behaviour change communication activities. | Benchmark description | Addition: “Monitoring systems systematically and routinely collect data on process indicators in order to track progress of programs or initiatives to ensure implementation and effectiveness.” | Existence | Effective | Need to include operational dimension to ensure properly functioning monitoring system. | |

| Scoring description | Addition of an operational element to scoring, i.e., the monitoring system should be used to track behaviour change communication activities. | |||||

| Scoring | Operational dimension added to scoring of minimal, partial, and major progress. | |||||

| CGMG1: There is a National Breastfeeding Committee/IYCF Committee. | Existence | Volume/frequency | Quality | |||

| CGMG2: National Breastfeeding Committee/IYCF Committee work plan is reviewed and monitored regularly. | Scoring description | Addition: “However, if the country does not have a National Breastfeeding Committee/IYCF Committee, this benchmark must be scored as no progress.” | Existence | Effective | Clarification of scoring. | |

| CGMG3: Data related to breastfeeding programme progress are used for decision making and advocacy. | Volume/frequency | |||||

Hromi‐Fiedler AJ, dos Santos Buccini G, Gubert MB, Doucet K, Pérez‐Escamilla R. Development and pretesting of “Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly”: Empowering governments for global scaling up of breastfeeding programmes. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12659 10.1111/mcn.12659

REFERENCES

- Aryeetey, R. , Hromi‐Fiedler, A. , Adu‐Afarwuah, S. , Amoaful, E. , Ampah, G. , Gatiba, M. , … Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2018). Ghana Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Committee. Pilot testing of the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly toolbox in Ghana. International Breastfeeding Journal, 13, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPNI/IBFAN‐Asia . (2014). World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative Assessment Tool. Available at: http://worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/docs/questionnaire-WBTi-September2014.pdf. Accessed on: March 18, 2018.

- Britto, P. R. , Lye, S. J. , Proulx, K. , Yousafzai, A. K. , Matthews, S. G. , Vaivada, T. , … Early Childhood Development Interventions Review Group, f. t. L. E. C. D. S. S. C (2017). Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia‐Chien Hsu, B. A. S. (2007). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12(10). [Google Scholar]

- Darmstadt, G. L. , Kinney, M. V. , Chopra, M. , Cousens, S. , Kak, L. , Paul, V. K. , … Lancet Every Newborn Study, G (2014). Who has been caring for the baby? Lancet, 384(9938), 174–188. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60458-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González de Cosío, T. , Ferré, I. , Mazariegos, M. , & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2018). Scaling up breastfeeding programs in Mexico: Lessons learned from the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly initiative. Current Developments in Nutrition. Available online at: https://academic.oup.com/cdn/article/2/6/nzy018/4985833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kitson, A. , Harvey, G. , & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7(3), 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet (2017). Breastfeeding: A missed opportunity for global health. Editorial. The Lancet, 390, 352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis, J. N. , Posada, F. B. , Haines, A. , & Osei, E. (2004). Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet, 364(9445), 1615–1621. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17317-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, A. C. , Kerber, K. , Pfitzer, A. , Morrissey, C. S. , Marsh, D. R. , Oot, D. A. , … Shiffman, J. (2012). Benchmarks to measure readiness to integrate and scale up newborn survival interventions. Health Policy Plan, 27(Suppl 3), iii29–iii39. 10.1093/heapol/czs046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C. , & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information Management, 42(1), 15–29. 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Curry, L. , Minhas, D. , Taylor, L. , & Bradley, E. (2012). Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low‐ and middle‐income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Advances in Nutrition, 3(6), 790–800. 10.3945/an.112.002873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , & Hall Moran, V. (2016). Scaling up breastfeeding programmes in a complex adaptive world. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(3), 375–380. 10.1111/mcn.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Hromi‐Fiedler, A. J. , Gubert, M. B. , Doucet, K. , Meyers, S. , & Dos Santos Buccini, G. (2018). Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index: Development and application for scaling‐up breastfeeding programmes globally. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e12596 10.1111/mcn.12596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Escamilla, R. , Segura‐Perez, S. , & Damio, G. (2014). Applying the Program Impact Pathways (PIP) evaluation framework to school‐based healthy lifestyles programs: Workshop Evaluation Manual. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35(3 Suppl), S97–S107. 10.1177/15648265140353S202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Lancet Breastfeeding Series, G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet, 387(10017), 491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkies, M. N. , Bowles, K. A. , Skinner, E. H. , Haas, R. , Lane, H. , & Haines, T. P. (2017). The effectiveness of research implementation strategies for promoting evidence‐informed policy and management decisions in healthcare: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 12(1), 132 10.1186/s13012-017-0662-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Council of State Governments . (2008). State policy guide: Using research in public health policymaking . Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5233 . Accessed on: March 25, 2018 Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5233

- The World Bank Group . (2018). World Bank Open Data. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed on March 18, 2018.

- United Nations Child Fund . (2013). Breastfeeding on the worldwide agenda: Findings from a landscape analysis on political commitment for programmes to protect, promote and support breastfeeding. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eapro/breastfeeding_on_worldwide_agenda.pdf. Accessed on: March 18, 2018.

- United Nations Child Fund, & World Health Organization . (2018). Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services—the revised Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi-implementation-2018.pdf?ua=1. Accessed on: August 26, 2018.

- United Nations Child Fund, & World Health Organization . (2017b). Tracking progress for breastfeeding policies and programmes: Global breastfeeding scorecard 2017. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf?ua=1. Accessed on: March 18, 2018.

- Victora, C. , Bahl, R. , & Barros, A. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet, 387, 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2003). Infant and young child feeding: A tool for assessing national practices, policies and programmes. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/inf_assess_nnpp_eng.pdf. Accessed on: March 18, 2018.