Abstract

Breastfeeding has many established benefits for mothers, children, and society at large; however, the vast majority of infants globally do not meet international breastfeeding recommendations. There are many complex reasons for suboptimal breastfeeding rates, including social and societal factors. Alongside increasing social media use worldwide, there is an expanding research focus on how social media use affects health behaviours, decisions and perceptions. The objective of this study was to systematically determine if and how breastfeeding is promoted and supported on the popular social media platform Instagram, which currently has over 700 million active users worldwide. To assess how Instagram is used to depict and portray breastfeeding, and how users share perspectives and information about this topic, we analysed 4,089 images and 8,331 corresponding comments posted with popular breastfeeding‐related hashtags (#breastfeeding, #breastmilk, #breastisbest, and #normalizebreastfeeding). We found that Instagram is being mobilized by users to publicly display and share diverse breastfeeding‐related content and to create supportive networks that allow new mothers to share experiences, build confidence, and address challenges related to breastfeeding. Discussions were overwhelmingly positive and often highly personal, with virtually no antagonistic content. Very little educational content was found, contrasted by frequent depiction and discussion of commercial products. Thus, Instagram is currently used by breastfeeding mothers to create supportive networks and could potentially offer new avenues and opportunities to “normalize,” protect, promote, and support breastfeeding more broadly across its large and diverse global online community.

Keywords: breastfeeding, content analysis, hashtags, Instagram, public health, social media

Key messages.

This systematic analysis of breastfeeding‐related content on Instagram evaluated 4,089 images and 8,331 comments.

We observed a diverse range of images accompanied by discussions that were overwhelmingly positive and supportive, with virtually no antagonistic content.

Instagram is currently used by breastfeeding mothers to create supportive networks and could potentially offer new avenues and opportunities to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding.

Instagram might be a useful platform for public health or educational campaigns to promote and “normalize” breastfeeding; however, there is little evidence of this occurring at present.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding has many established benefits for mothers, infants and society at large. These include lowering the risk of infant mortality, protecting against infections, and preventing chronic diseases in mothers and their breastfed children (Victora et al., 2016), yielding considerable economic benefits at the population level (Rollins et al., 2016). Based on this evidence, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months and continued breastfeeding until 2 years of age and beyond (WHO, 2017); however, most infants around the world are not meeting these recommendations (Victora et al., 2016). Only 26% of Canadian infants born in 2012 were exclusively breastfed for 6 months (Statistics Canada, 2015), and rates are even lower in the United States (19%, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), Australia (15%, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011), and the United Kingdom (1%, UK National Health Service, 2012).

1.1. Reasons for suboptimal breastfeeding rates

There are multiple complex and interconnected reasons for low breastfeeding rates, but overall and generally speaking, “the world is still not a supportive and enabling environment for most women who want to breastfeed” (Rollins et al., 2016). Although physiological factors can influence a woman's ability to breastfeed, social and societal factors have an arguably larger impact on breastfeeding decisions and practices (Niela‐Vilén, Axelin, Melender, & Salanterä, 2015; Rollins et al., 2016; Sriraman & Kellams, 2016). Although breastfeeding is instinctual for babies, it is a learned skill for new mothers. Studies have shown that lack of prenatal breastfeeding education and low breastfeeding self‐efficacy are associated with lower breastfeeding initiation rates and increased odds of feeling underprepared to deal with breastfeeding difficulties (Sriraman & Kellams, 2016; A. Brown, 2016; Niela‐Vilén et al., 2015). The aggressive marketing campaigns of infant formula companies can also undermine mothers' confidence in breastfeeding (Sriraman & Kellams, 2016), as can unsupportive partners or family members, and restrictive work environments (Rollins et al., 2016; Sriraman & Kellams, 2016).

New mothers also face challenges related to breastfeeding in public. Even though it is protected by law in many countries, some people remain uncomfortable with this practice (Grant, 2016; Sriraman & Kellams, 2016; A. Brown, 2016) and react with hostility or disapproval towards nursing mothers (Grant, 2016; Khoday & Srinivasan, 2013; Rollins et al., 2016). Instances of women being told to “cover up” or take their breastfeeding elsewhere are common and have garnered significant attention from the popular press (Dolski, 2016; Rumley, 2016; Snowdon, 2017). As a result, many mothers feel hesitant to breastfeed in public (Grant, 2016), and this may negatively influence their decision to initiate or continue breastfeeding. In a UK survey of mothers' experiences and attitudes towards breastfeeding (A. Brown, 2016), respondents agreed that increased education and promotion could help improve breastfeeding rates. They felt that such efforts should target society at large rather than mothers specifically, because the majority of mothers intend to breastfeed but do not achieve their own breastfeeding goals due to inadequate clinical and social support. Mothers also felt that promotional efforts should focus on “normalization” of breastfeeding as the usual way to feed babies, rather than the common yet divisive “breast is best” messaging.

1.2. Breastfeeding promotion campaigns

Social campaigns have been deployed to promote breastfeeding by increasing awareness of its health benefits, combatting negative attitudes, and fostering support for breastfeeding mothers (Snyder, 2007). These include longstanding initiatives such as World Breastfeeding Week, coordinated by the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action, as well as newer campaigns like the Public Breastfeeding Awareness Project on Facebook. Additional efforts have involved breastfeeding celebrities posing for magazines or posting breastfeeding selfies (“brelfies”) on their personal social media sites (US Weekly Staff, 2017).

There is evidence that social campaigns can positively impact breastfeeding rates (Snyder, 2007). For example, campaigns in Vietnam successfully raised breastfeeding rates from 26% in 2011 to 48% in 2012 (Sriraman & Kellams, 2016). Concerns have also been raised, however, regarding potential negative consequences of “breast is best” campaigns (A. Brown, 2016; Da Silva Trammel, 2017; Grant, 2016; Jung, 2015; Koerber, 2013), which may induce guilt among women who experience breastfeeding difficulties (A. Brown, 2016; Hauck & Irurita, 2003; Holcomb, 2017; Kukla, 2006; Labbok, 2008; Talmazan, 2017). Social media platforms, where users play an increasingly active role in the kinds of information they receive, might offer a unique space where constructive breastfeeding promotion, support, and education can take place.

1.3. Instagram

Social media or social‐networking platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube are extremely popular worldwide (Alexa, 2017). Instagram is a platform focused on sharing photos and videos that currently has more than 700 million active users worldwide (Instagram, 2017; Statista, 2018). Approximately 28% of Americans and 20% of Canadians use Instagram (McKinnon, 2016; PEW, 2017). In the United States, Instagram is more commonly used by women than men (32% to 23%) and by a younger demographic (59% are between the ages of 18–29 years and 31% between 30 and 49; PEW, 2017).

Instagram enables interactions among users in both “strong‐tie” networks (i.e., family, offline friends, etc.) as well as larger “weak‐tie” networks (unknown users who are also on Instagram; Waterloo, Baumgartner, Peter, & Valkenburg, 2017). This type of weak‐tie interaction can take place through hashtagging, where users append videos or images with a hashtag (e.g., #breastfeeding), allowing public content to be searched for and interacted with. Hashtagged content creates discursive communities which construct and coordinate information and perspectives around various themes and topics (Highfield & Leaver, 2015; Rambukkana, 2015).

Scholars have begun analysing how social media influences individuals' understanding and decisions related to health topics (Centola, 2013). Instagram has been found to have positive and negative influences. For example, using Instagram has been linked with increased mental anxiety and depression (Lup, Trub, & Rosenthal, 2015) but has also been highlighted as a medium for promoting self‐confidence and positive body images (Cwynar‐Horta, 2016: Salam, 2017). Research has explored how nutritional information is shared and reflected upon by Instagram communities (Sharma & De Choudhury, 2015), how images taken in restaurants correlate with obesity patterns (Mejova, Haddadi, Noulas, & Weber, 2015), and how a fitness campaign (“fitspiration”) had counterintuitive effects on this platform (Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2016).

Studies have shown that breastfeeding mothers use social media for education, advice, and social support (Asiodu, Waters, Dailey, Lee, & Lyndon, 2015; Tomfohrde & Reinke, 2016). Although some social media platforms have been criticized in the past for forbidding images of breastfeeding (Locatelli, 2017; Moss, 2015), Instagram's current policies are breastfeeding‐friendly, stating explicitly that photos of breastfeeding are allowed (Instagram, 2018). To our knowledge, only one small qualitative study has analysed breastfeeding on Instagram (Locatelli, 2017).

The objective in our study was to systematically determine if and how breastfeeding is promoted and supported on Instagram. We characterized images and user discussions related to breastfeeding to assess how Instagram is used to depict and portray breastfeeding, and how users share perspectives and information about this topic. Finally, we specifically searched for evidence of supportive and antagonistic discourse within these discussions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data collection

After an extensive Instagram search exploring commonly used hashtags related to breastfeeding (Data S1 and S2), we identified the four most common (#breastfeeding, #breastmilk, #breastisbest, and #normalizebreastfeeding), and recorded the total number of images for each. We determined that a minimum of 663 images per hashtag (approximately one complete week of postings) would be required to achieve a confidence level of 99% (confidence interval, 5) for representing the total images present on Instagram for each hashtag. We selected the complete week of January 9–16, 2017, to construct our data set for analysis. Using Instagram's application programing interface (API), which allows programmers to access the code governing Instagram's public content, the images and their captions and comments were compiled and organized in a custom software platform. All videos as well as the duplicates of one image which had been shared 10 times by the same user were removed, leaving 4,089 images with a total of 20,532 comments. Not all 4,089 images were unique because some had been tagged with two or more of the four hashtags. These duplicate images were retained for analysis because they were contributing to multiple hashtag groups and discussions.

2.2. Data analysis

Content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004) was performed first on images and then on comments, using inductive and deductive coding methods (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). This approach is based on “grounded theory” (Charmaz, 2014), where the data being analysed play a substantive role in constructing the analytical lens. The lens is adapted as patterns or substantial elements in the data emerge, and a sample of the data is analysed in order to construct coding frames. The complete image and comment coding frames are provided as supplementary material (Data S3 and S4).

For images, the coding frame was built to first capture the general type of image followed by specific details about the people, objects, locations, and activities depicted, including the presence of brands, logos, and text. For comments, all images with six or more comments were considered to have elicited “substantial discussion” and were eligible for analysis. Captions were coded first, followed by the corresponding comment discussion thread, assessing the functional characteristics present in each comment (e.g., praising or complimenting, critiquing, asking a question, etc.), with each functional characteristic counting only once per comment. Non‐English threads were identified and counted but not coded. If a caption included only hashtags, the caption was coded as “other.”

Coding of images and comments was undertaken by a team of coding volunteers who participated in a training session in order to ensure consistency. To confirm reliability, image coding was reviewed for consistency, and discrepancies were resolved by one of the principal coders. Intercoder reliability was performed on the comment coding. A mean kappa score of k = 0.75 across all categories demonstrates agreement among coders (Landis & Koch, 1977; McHugh, 2012). Finally, a Word Cloud was generated on http://www.wordle.net using comments from all #breastfeeding images, excluding common English words and non‐English words. The Word Cloud was used to visualize the comment discussions, not as a methodological tool to analyse comments or draw conclusions.

3. RESULTS

Our initial dataset included 4,089 Instagram images with a total of 20,532 posted comments. Table 1 shows the number of images and comments by hashtag. Of the four hashtags considered, #breastfeeding was the most common, with 1,305 images and 5,281 comments (median two comments per image), whereas #breastisbest was the least common, with 726 images and 3,107 comments (median three comments per image).

Table 1.

Total images and associated comments posted on Instagram using the top four breastfeeding‐related hashtags from January 9–16, 2017

| Hashtag | Total images posted | Total comments posted | Comments per image | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Max | |||

| #breastfeeding | 1,305 | 5,281 | 4.1 | 2 | 348 |

| #breastmilk | 1,120 | 7,886 | 7.0 | 2 | 2,180 |

| #normalizebreastfeeding | 938 | 4,258 | 4.5 | 3 | 74 |

| #breastisbest | 726 | 3,107 | 4.3 | 3 | 105 |

| Total | 4,089 | 20,532 | 5.0 | 2 | 2,180 |

3.1. Images

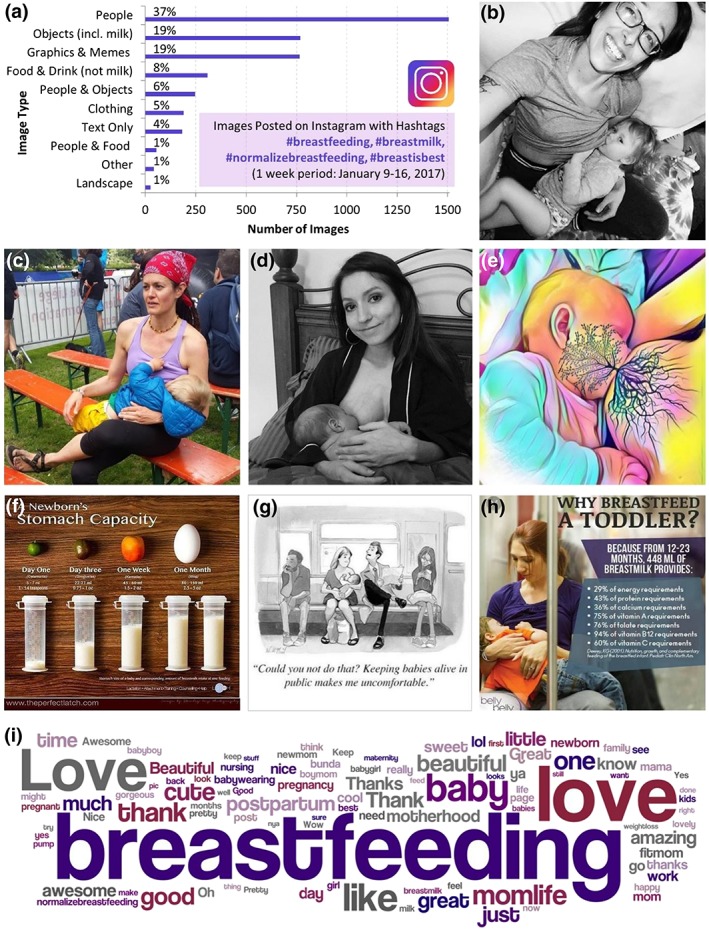

The most common image types across all four hashtags included photos of people (n = 1,505/4,089, 37% of all images), objects (n = 767/4,089, 19%) and graphics and memes (n = 764/4,089, 19%; Figure 1a). Examples of these image types are shown in Figure 1b–h. Because they were the most common, these image types were investigated in greater detail (Table 2). Other less common image types included food and drink (e.g., lactation teas and cookies), clothing (e.g., nursing tops), and text only (e.g., quotes and information).

Figure 1.

Breastfeeding‐related content on Instagram. (a) Most common image types posted using the four most popular breastfeeding‐related hashtags (#breastfeeding, #breastmilk, #normalizebreastfeeding, and #breastisbest; n = 4,089 total images) from January 9–16, 2017. (b–h) Examples of image types including (b) people (subtypes: breastfeeding, infant), shared with permission from @mamasmilknochaser; (c) people (breastfeeding, toddler, outdoors, and public location), shared with permission from @fitafter; (d) people (breastfeeding, toddler, and selfie), shared with permission from @loothtooth; (e) graphic and meme (Tree of Life), shared with permission from @tereserohman; (g) graphic and meme (breastfeeding reflection or opinion); (f,h) graphic and meme (image with text—breastfeeding information). (i) Word cloud generated from comments associated with all #breastfeeding images with six or more comments; word size reflects frequency of occurrence

Table 2.

Analysis of most common image types across top four breastfeeding‐related hashtags on Instagram from January 9–16, 2017 (N = 4,089)

| Image type or subtype categories or features | No. of images | % of total images (N = 4,089) | % of defined subset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peoplea | 1,806 | 44.2 | % of images with people (n = 1,806) |

| Infants and children | 1,731 | 42.3 | 95.9 |

| Newborns | 408 | 9.9 | 22.6 |

| Infants | 823 | 20.1 | 45.6 |

| Toddlers | 237 | 5.8 | 13.1 |

| Older children | 66 | 1.6 | 6.1 |

| Age unclear | 197 | 11.4 | |

| Women | 1,639 | 40.1 | 90.8 |

| Men | 100 | 2.5 | 5.5 |

| People's ethnicities | |||

| White | 1,601 | 39.2 | 88.6 |

| Black | 190 | 4.7 | 10.5 |

| Other | 276 | 6.8 | 15.2 |

| People's activities | |||

| Breastfeeding | 860 | 21.0 | 47.6 |

| Posing | 624 | 15.3 | 34.6 |

| Posing while pregnant | 36 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| Doing physical activities | 35 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Pumping breast milk | 27 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Bottle‐feeding | 19 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Posing in hospital | 7 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Other (including no activity) | 198 | 4.8 | 10.9 |

| People breastfeeding | 860 | 21.0 | % of breastfeeding images (n = 860) |

| Multitasking | 78 | 1.9 | 9.0 |

| Partially visible breast | 672 | 16.4 | 78.1 |

| Completely covered breast | 188 | 4.6 | 21.9 |

| Outdoors | 95 | 2.3 | 11.1 |

| Public locations | 118 | 2.9 | 13.7 |

| Selfie | 287 | 7.0 | 33.4 |

| Objectsb | 1,160 | 28.4 | % of images with objects (n = 1,160) |

| Not related to babies or breastfeeding | 270 | 6.6 | 23.3 |

| Related to babies or breastfeeding | 890 | 21.8 | 76.7 |

| Objects related to babies or breastfeeding | 890 | 21.8 | % of breastfeeding object images (n = 890) |

| Equipment (e.g., breast pump) | 278 | 6.8 | 31.2 |

| Milk in a bottle | 226 | 5.5 | 25.4 |

| Milk in a bag | 130 | 3.2 | 14.6 |

| Baby toys | 64 | 1.6 | 7.2 |

| Other | 212 | 5.2 | 23.8 |

| Graphics and memes | 764 | 18.7 | % of graphic or meme images (n = 764) |

| Tree of Life | 193 | 4.7 | 25.6 |

| Breastfeeding reflection or opinion | 156 | 3.8 | 20.4 |

| Website screenshots | 48 | 1.2 | 6.3 |

| Instructional | 37 | 0.9 | 4.8 |

| Breastfeeding “awards” | 36 | 0.9 | 4.7 |

| Other | 294 | 7.2 | 38.5 |

| Images with text | 850 | 20.8 | % of images with text (n = 850) |

| Motivational quotes | 179 | 4.4 | 21.1 |

| Breastfeeding information | 168 | 4.1 | 19.8 |

| Instructional | 58 | 1.4 | 6.8 |

| Other | 445 | 10.9 | 52.3 |

| Promotional and sharing | 978 | 23.9 | |

| Brand names or logos | 714 | 17.5 | |

| Social media (e.g., logos and user IDs) | 229 | 5.6 | |

| Non‐commercial organizations | 35 | 0.9 | |

| Antagonistic content | 20 | 0.5 | |

Note. Totals do not always sum to 100% because not all subcategories are mutually exclusive.

Includes “people,” “people + object,” and “people + food” image types.

Includes “object” and “people + object” image types, as well as objects featured predominantly in “Graphics or Memes.”

3.1.1. People

Almost half (n = 1,806/4,089, 44%) of all images contained a focus on people. These images primarily depicted women (n = 1,639/1,806, 91% of all images containing people) and children (n = 1,731/1,806, 96%) and rarely included men (n = 100/1,806, 6%). Children were mostly newborns (n = 408/1,806, 23%) or infants (n = 823/1,806, 46%) although toddlers (n = 237/1,806, 13%) and older children (n = 66/1806, 4%) were also present. Overall, the majority of people pictured were White (n = 1,601/2,067, 77%), with the remainder classified as Black (n = 190/2,067, 9%) or other ethnicities (n = 276/2,067, 13%, including Hispanic, Asian, South‐East Asian, and Middle‐Eastern).

3.1.2. People's activities

The most common activity depicted was breastfeeding (n = 860/1,806, 48% of images containing people; n = 860/4,089, 21% of all images; Figure 1b–d), but there were also a large number of images in which people were “just posing,” (n = 624/4,089, 15%). Among the images that depicted breastfeeding, 9% (n = 78/860) were images of women breastfeeding while doing another activity (“multitasking”) such as physical activities (yoga, hiking, biking, tobogganing, stand‐up paddle boarding); shopping; using a computer; travelling on public transit; eating, drinking, and preparing food; and playing and/or reading with other children. The majority of breastfeeding images showed a partially visible breast (n = 672/860, 78%) rather than a completely covered breast (n = 188/860, 22%). In addition, 11% (n = 95/860) of the breastfeeding images were taken outdoors, 14% (n = 118/860) appeared to be in public locations (Figure 1c), and 33% (n = 287/860) were “selfies” (a self‐portrait taken on a smartphone; Figure 1b). A relatively small number of images depicted women bottle‐feeding or pumping breast milk (n = 19/4,089, 0.5% and n = 27/4,089, 0.7% of all images, respectively).

3.1.3. Objects

Over a quarter of all images (n = 1,160/4,089, 28%) featured objects. Breastfeeding equipment (e.g., pumps and drying racks) was the most common type of object depicted (n = 278/4,089, 7%), followed by milk in a bottle (n = 226/4,089, 6%) and milk in a bag (n = 130/4,089, 3%). Other objects (n = 212/4,089, 5%) included jewellery (sometimes breastmilk jewellery), oils, ointments, creams, balms, and bottles of supplements.

3.1.4. Graphics and text

Nearly one in five images (n = 764/4,089, 19%) were graphics or illustrations or memes. The most common subtype in this category was “Tree of Life” (n = 193/4,089, 5%), a popular style of breastfeeding image produced using photo‐editing software, PicsArt App, to apply a colourful hand‐painted effect and illustrate a system of roots connecting the mother's breast to her nursing infant (Levy, 2017; Figure 1e). Images presenting a reflection or opinion related to breastfeeding were also common (n = 156/4,089, 4%, Figure 1f). Screenshots of other websites, instructional images, or images of congratulatory breastfeeding awards had a much smaller presence (n = 48/4,089; n = 47/4,089; n = 36/4,089, ~1% each). Although approximately 5% (n = 184/4,089) of all images contained only text, 21% (n = 850/4,089) contained some text, including motivational quotes (n = 179/4,089, 4%) and breastfeeding information, statistics, or facts (n = 168/4,089, 4% Figure 1g–h). Instructional text had a significantly smaller presence (n = 58/4,089, 1%). The “Other” images in this category (n = 445/4,089, 11%) mostly included non‐English text and were therefore not analysed in detail.

3.1.5. Promotion and sharing

There was a fairly large presence of brand names and/or logos, present in 714 images (n = 714/4,089, 17%). Although a quantitative analysis was not performed, these images were scanned specifically for major infant formula brands (e.g., Nestlé®, Abbot Similac®, and Mead Johnson®), and these were not observed. Brands which had a considerable presence included Spectra®, Lansinoh®, GabaG®, Bagbit®, and Medela®, companies that manufacture breastfeeding‐related products including breast pumps. Other brands present, mostly in images with non‐English captions, included Moeder® and Vitamilk®, products intended to boost breastmilk production. Organizational logos and URLs representing non‐commercial organizations (e.g., La Lecha League®) had a very small presence (<1%).

3.1.6. Antagonistic content

The total number of images judged to be antagonistic (defined as argumentative, hostile, or critical) was 20, representing less than 0.5% (n = 20/4,089) of all images. Although this presence was small, we analysed the 20 images and determined that 14 were critiques concerning the sexualization of breasts and/or the stigmatizing of breastfeeding in public. Two raised issues concerning the stigmatizing of women who do not nor cannot breastfeed. The last four images raised “other” issues related to breastfeeding including race, breastfeeding at work, and the factual benefits of breastfeeding.

3.1.7. Different hashtags

Although significant overlap was observed across the images identified by the four different hashtags (#breastfeeding, #breastmilk, #normalizebreastfeeding, and #breastisbest), some distinct hashtag‐specific patterns also emerged (Table 3). Overall, #breastfeeding captured the most general and heterogeneous group of images, having the lowest standard deviation of image types (12%), and the highest percentage of people “just posing” (n = 280/1,305, 21%). In contrast, #normalizebreastfeeding had the highest standard deviation (20%), focused primarily on people (included in n = 560/938, 60% of images), and had by far the highest percentage of images depicting breastfeeding (n = 369/938, 39%, compared with 6%–23% in the other hashtag groups). The hashtag #breastmilk identified more object‐focused images (n = 404/1,120, 36%), considerably higher than the other three data sets. Graphics and memes appeared in similar proportions across all hashtag groups, whereas brand names and logos where much more common in the #breastfeeding and #breastmilk groups. Lastly, although the presence of antagonistic images was scant across all hashtags, #breastisbest featured nearly three times the proportion of antagonistic images (n = 10/726, 1.4%)compared with the other hashtags (0.1%–0.4%).

Table 3.

Types of images posted using the top four breastfeeding‐related hashtags on Instagram from January 9–16, 2017 (N = 4,089)

| Image type | #breastfeeding | #breastmilk | #normalize breastfeeding | #breastisbest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,305 | n = 1,120 | n = 938 | n = 726 | |

| People | 36% | 22% | 52% | 41% |

| Objects (incl. bags or bottles of milk) | 14% | 36% | 7% | 15% |

| Graphics and memes | 16% | 18% | 22% | 19% |

| Food and drink (not milk) | 10% | 9% | 3% | 6% |

| People and objects | 4% | 6% | 7% | 8% |

| Clothing | 9% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Text only | 5% | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| People and food | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Other | 1% | 0% | 1% | 2% |

| Landscapes | 1% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Standard deviation | 12% | 14% | 20% | 15% |

| Combined % of top two image types | 53% | 58% | 74% | 60% |

| Selected image subtypes | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 14% | 6% | 39% | 23% |

| Breastfeeding and other activity | 1% | 1% | 4% | 2% |

| Just posing | 21% | 10% | 15% | 13% |

| Brand names and logos | 21% | 26% | 8% | 11% |

| Antagonistic content | 5 (0.38%) | 4 (0.36%) | 1 (0.11%) | 10 (1.38%) |

Note. Darkness of purple shading reflects magnitude of proportions.

3.2. Captions, comments, and discussions

The total number of images with at least six comments was 1,016. Following the removal of duplicate images and videos, 819 unique images remained with a total of 13,945 posted comments. Of these, 8,331 (60% of eligible comments) were retrieved after excluding comments consisting of graphics and emojis (facial expression graphics) without any text, comments deleted by users, and comments exceeding the maximum number of comments able to be retrieved through Instagram's API. A minority of discussions (n = 107/819, 13% were not in English; of these, 43% (n = 46/107) were in Indonesian, 11% (n = 12/107) were in Spanish, and 9% (n = 10/107) were in German. An additional 15 languages were represented (Data S5). The remaining 712 images contained English language discussions and comprised a total of 6,999 comments, which were analysed in detail. The most common image caption elements and comment discussion elements are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Captions and comment discussions associated with images posted on Instagram using the top four breastfeeding‐related hashtags from January 9–16, 2017

| Image caption elements | No. (%) of total caption elements (N = 871) | % of captions (N = 712) |

|---|---|---|

| Reflecting positively on breastfeeding or pumping | 146 (16.8%) | 146 (20.5%) |

| Praising products, customers, or stores | 134 (15.4%) | 134 (18.8%) |

| Reflecting on parenthood but not breastfeeding | 124 (14.2%) | 124 (17.4%) |

| Reflecting on the struggles of breastfeeding | 100 (11.5%) | 100 (14.0%) |

| Other | 80 (9.2%) | 80 (11.2%) |

| Neutral reflection on breastfeeding (comments without valuation) | 76 (8.7%) | 76 (10.7%) |

| Praising or complimenting of baby generally | 68 (7.8%) | 68 (9.6%) |

| Website or blog promotion including prizes, giveaways, and so forth | 39 (4.5%) | 39 (5.5%) |

| Reflecting on other personal experiences (not parenthood or breastfeeding) | 26 (3.0%) | 26 (3.7%) |

| Asking a question (nonrhetorical) | 24 (2.8%) | 24 (3.4%) |

| Offering advice or tips on breastfeeding | 16 (1.8%) | 16 (2.2%) |

| Critiquing society and raising social issues around breastfeeding | 15 (1.7%) | 15 (2.1%) |

| Offering advice or tips generally | 9 (1.0%) | 9 (1.3%) |

| Offering advice or tips on motherhood, womanhood | 8 (0.9%) | 8 (1.1%) |

| Supporting women who cannot breastfeed | 4 (0.5%) | 4 (0.6%) |

| Critiquing society and raising social issues generally | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Raising social issues related to stigmatizing women who cannot breastfeed | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Negative reflection on breastfeeding in public | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Comment discussion elements | No. (%) of total discussion elements (N = 8,856) | % of discussions (N = 712) |

|---|---|---|

| Praising or complimenting (“great,” “love it,” etc.) | 3,101 (35.0%) | 653 (91.7%) |

| Including another name (Instagram user's name, twitter name, etc.) | 2,418 (27.3%) | 569 (79.9%) |

| Thanking | 645 (7.3%) | 332 (46.6%) |

| Other | 488 (5.5%) | 242 (34.0%) |

| Reflecting on personal experiences related to struggles of breastfeeding | 372 (4.2%) | 140 (19.7%) |

| Requesting information (asking nonrhetorical questions) | 368 (4.2%) | 223 (31.3%) |

| Expressing empathy and/or motivating (“sorry for you,” “you can do it,” etc.) | 298 (3.4%) | 157 (22.1%) |

| Reflecting on personal experiences related to parenthood but not breastfeeding | 260 (2.9%) | 84 (11.8%) |

| Reflecting positively on personal breastfeeding experiences | 243 (2.7%) | 107 (15.0%) |

| Recommending products | 214 (2.4%) | 110 (15.4%) |

| Giving advice or tips but not recommending products | 133 (1.5%) | 76 (10.7%) |

| Expressing desire to follow account | 98 (1.1%) | 90 (12.6%) |

| Reflecting positively on the act of breastfeeding (not personal reflection) | 88 (1.0%) | 46 (6.5%) |

| Reflecting on society negatively | 50 (0.6%) | 16 (2.2%) |

| Reflecting on other personal experiences (not parenthood or breastfeeding) | 36 (0.4%) | 14 (2.0%) |

| Disagreeing with image, caption, or another user | 18 (0.2%) | 11 (1.5%) |

| General complaining | 11 (0.1%) | 10 (1.4%) |

| Reflecting on society positively | 8 (0.1%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| Critiquing or expressing discomfort about breastfeeding | 4 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| Critiquing or expressing discomfort about breastfeeding in public | 3 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

Note. Categories are not mutually exclusive; a caption or comment may contain multiple elements. After removing videos and duplicate images, 712 unique images qualified for comment analysis by having six or more comments predominantly in English. Each image had one caption (containing one or more caption elements) and at least six comments (each containing one or more discussion elements).

The topic of breastfeeding was discussed extremely positively, with users offering compliments and praise (n = 653/712, 92% of discussions), thanking one another (n = 332/712, 47% of discussions), and reflecting positively on personal breastfeeding experiences (n = 146/712, 21% of captions and n = 107/712, 15% of discussions). This positivity is reflected in Figure 1i, a Word Cloud generated from comment discussions, where the most prominent words include like, love, good, great, beautiful, amazing, awesome, and thanks.

Discussions often conveyed a sense of collaboration and community. It was common for users to offer personal reflections on the difficult aspects of breastfeeding (personal struggles), with 14% (n = 100/712) of all captions and 20% (n = 140/712) of all discussions including at least one instance of such reflections. These comments were consistently met with positivity and support, with over one fifth of all discussions (n = 157/712, 22%) including at least one instance of a user expressing empathy or offering motivational support to another user. For example, one user posted an image of a breast pump, captioned:

“In this moment I honestly felt defeated. When my fiancé asked me why I was crying, I blamed it on postpartum and hormones, but we both knew that wasn't the only cause. In one hand I held this pump, both happy and sad simultaneously. Happy because this was my first pumping experience and I was damn proud about that. Sad because I start work soon and with the amount of work that pumping takes, I didn't think I could do it or produce enough … even now I still underestimate my abilities... I am both filled with excitement and sorrow. I am a burst of energy and extremely exhausted.”

Other users responded with encouragement (“Congratulations mama ‐ be easy with yourself, you are doing amazing and you are holding liquid gold!”), empathy (“It is not easy, but with time will become easier”), advice (“Before and after feedings lots of skin to skin as well will help”), and appreciation (“Thank you so much for that. It feels good hearing from other mothers who have actually experienced what I am going through.”)

It was also common for users to solicit information from one another. Although “requesting information” accounted for only 4% (n = 368/8,856) of all comment elements, nearly a third (n = 223/712, 31%) of all discussions included at least one instance of this discursive action. For example, one user posted “Fellow breastfeeding mothers, what do you do to make the frequent feedings bearable?” and received responses including “I tried to remember each time that I would miss it when it was over. And I do!” and “Honestly I just accepted that they are going to happen, that it's great for my supply and that it's normal” and “I remember crying all the time the first few weeks, trust me it will get better! Keep it up and good luck!” There was also substantial discussion and solicitation of information about brands and products. The second most common caption element (n = 134/712, 19%) was focused on praising products or stores, and 15% (n = 110/712) of discussions included at least one instance of recommending products.

Critiquing, complaining, and antagonism were rarely observed (<5% of all discussions). When they did occur, these critical statements were often related to public intolerance of breastfeeding (e.g., “This is normal. This is my son eating. This does NOT need to be covered up. This is his right to be fed.”). Such statements were consistently met with supportive comments from other users (e.g., “Unreal! I'm so sorry”, “That's insane and not okay. It also goes against discrimination laws and the charter of rights and freedoms”, and “It's your right to feed #anywhereanytime”).

Lastly, 13% (n = 90/712) of discussions explicitly involved users expressing a desire to follow another user's account, demonstrating the creation and growth of Instagram communities through the creation of new “weak ties”.

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic analysis of breastfeeding‐related content on the social media platform Instagram, evaluating over 4,000 images and 8,000 comments, we observed a diverse range of images accompanied by discussions that were overwhelmingly positive and supportive, with virtually no antagonistic content. The overall impression of breastfeeding on Instagram was celebratory, often expressed using a journalistic approach to share personal opinions, experiences, or struggles related to breastfeeding. With relatively little focus on education or instruction, Instagram currently appears to be a space for reflection and personal expression, where users connect and share with like‐minded individuals in both strong‐tie and weak‐tie networks that provide social support to address challenges and encourage breastfeeding.

4.1. Instagram as a “public” platform for diverse breastfeeding‐related content

Interestingly, we found that images shared on Instagram using popular breastfeeding‐related hashtags were not exclusively focused on women breastfeeding. They also include images of breastfeeding‐related objects, clothing, and food, as wells as creative graphics, illustrations, and memes. This diversity of images is consistent with the qualitative analysis conducted by Locatelli (2017), which also showed a wide range of images related to breastfeeding on Instagram. Still, people‐focused images were the most common type of image observed, and breastfeeding was the most common activity depicted.

Although we did not have access to user profile information (e.g., age, sex, and nationality), we observed that adults depicted in breastfeeding‐related images were primarily White and almost exclusively women. This “gender gap” identifies a potential opportunity to engage male Instagram users in social media campaigns to support breastfeeding—including men in general and fathers in particular, who have an important but underappreciated impact on their partners' breastfeeding experience (Brown & Davies, 2014; Rempel, Rempel, & Moore, 2017). While the under‐representation of non‐White ethnicities may be related to the English hashtags we studied, it also reflects the well‐known ethnic disparities in breastfeeding in developed countries (Jones, Power, Queenan, & Schulkin, 2015). Further research is warranted to study and enhance the engagement of different sociodemographic groups in breastfeeding‐related interactions on Instagram.

Our analysis also shows that different hashtags create different kinds of image‐based storylines and discourse. For example, #breastfeeding covered the most wide‐ranging types of images, #breastmilk focused on images of breastfeeding‐related objects such as breast pumps and bottles or bags of milk, #normalizebreastfeeding was most concentrated on images of women breastfeeding, and #breastisbest was most likely to contain antagonistic content, although such content was rare even in this group. This information could potentially be used to inform and target Instagram‐based campaigns to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding.

About 13% of images depicting breastfeeding were taken in public locations, suggesting that some women are using Instagram to promote breastfeeding in public. Many of these images featured women who were simultaneously performing other activities, illustrating that breastfeeding is compatible with a busy and active lifestyle. Arguably, images taken in private locations could also be considered “public” once posted on Instagram, because this and other social media platforms constitute a blending, reformatting, and reimagining of what is public (Boyd & Ellison, 2007; Jin, Phua, & Lee, 2015; Van Dijk, 2013). In this regard, women sharing and tagging their content with popular Instagram hashtags are projecting representations of themselves and their activities (including breastfeeding) in a publicly accessible environment where they can help shape public perspectives about breastfeeding.

4.2. Instagram communities as breastfeeding support networks for new mothers

With increasing social media use globally among all age groups, understanding the influence of social media on health behaviours and attitudes has become an important but challenging task. There is a growing market for social media content targeted to expecting and new mothers (Hearn, Miller, & Fletcher, 2013), and online breastfeeding support groups are seen as a valuable resource (Cowie, Hill, & Robinson, 2011). Research has shown that breastfeeding‐focused Facebook pages can enhance knowledge, provide emotional support, and improve breastfeeding intentions among users (Jin et al., 2015). Our results suggest that Instagram communities may offer similar benefits.

Although our study cannot provide concrete evidence that women are using Instagram to build confidence in their breastfeeding abilities, our results suggest that participating in online discussions about this topic may promote comfort, confidence, and self‐efficacy. The fact that women are choosing to share their images and experiences using Instagram suggests they are benefiting from this practice, perhaps by receiving support from the Instagram community to help them attain their breastfeeding goals. The discussions accompanying these images certainly support this hypothesis, as they were overwhelming positive and supportive, with users frequently complimenting and thanking one another, and reflecting positively on breastfeeding experiences. There were also many instances of users expressing difficulties with breastfeeding or pumping breastmilk, and these were consistently met with empathy, motivational sentiments, and advice or recommendations to address specific challenges. Thus, it is evident that supportive breastfeeding communities are present on Instagram. This observation is reinforced by the virtual absence of critical or antagonistic comments across all of the discussions we reviewed, and perhaps distinguishes Instagram from other social media platforms where aggressive or hostile reactions to breastfeeding‐related content might be more common.

We also found evidence of networking within breastfeeding‐related discussions. Approximately 12% of discussions involved a user explicitly requesting to follow an account, indicating new weak‐tie connections and expansion of social networks. This is further supported by the fact that nearly 80% of all discussions include a user mentioning another user's name in order to involve them in the discussion. Though not quantified in our analysis, this suggests the possible spreading of information through both strong and weak‐tie discursive networks, the latter of which is thought to play a key role in providing exposure to novel information and perspectives (Granovetter, 1973; Kavanaugh, Reese, Carroll, & Rosson, 2005; Levin & Cross, 2004).

4.3. Instagram as a potential platform for breastfeeding education and promotion

Notably, we observed very little educational content in breastfeeding‐related images or discussions, contrasted by a significant presence of commercial brand‐related images and product‐related discussions. It is well known that corporate entities make use of Instagram for marketing (Carah & Shaul, 2016) by hiring celebrities or “influencers” with large followings to post sponsored content and endorsements (K. Brown, 2016). It was beyond the scope of our study to analyse these practices, but importantly, major infant formula companies were not found to be infiltrating the Instagram breastfeeding community in any capacity.

Although social media platforms offer cost‐effective opportunities to disseminate health information to large networks (Asiodu et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2015), further research is required to understand the complex relationships formed on these platforms and determine how best to engage them for health promotion (Asiodu et al., 2015; Cowie et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2015). Our results indicate that public health initiatives are not currently using Instagram as a platform to support breastfeeding education or awareness, yet the Instagram environment appears to be highly supportive towards breastfeeding. Instagram might therefore represent an underutilized zone where campaigns to support or promote breastfeeding could direct more focus, although it remains to be seen how Instagram users would perceive or engage with such initiatives. The feasibility and potential impact of a public educational campaign on Instagram is unclear because users largely determine the content they are exposed to by following specific hashtags and users based on their personal interests, although content can also be targeted and promoted to specific user demographics.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the relatively large number of images and comments evaluated, and the systematic yet adaptive manner in which the analytical lens was developed to map out the discursive interactions taking place around breastfeeding on Instagram. There are two main limitations to this study. First, our analysis was limited to the four most popular hashtags, so it is possible that the complete diversity of breastfeeding‐related content on Instagram was not fully captured. Second, we were not able to retrieve all posted comments for analysis due to the use of emojis (graphics) that could not be imported, deletion of comments by users, and API limitations. Regardless, we captured nearly 60% of all eligible comments (8,331 of 13,945), which was more than sufficient for a detailed and comprehensive analysis. Future research on this topic could include additional hashtags, an intensive network analysis (tracking interactions between various accounts), or a follow‐up survey with users to further assess their objectives and motivations for sharing breastfeeding‐related content on Instagram.

5. CONCLUSIONS

There are legitimate public health and economic concerns over suboptimal breastfeeding rates worldwide. New mothers seeking to breastfeed face numerous individual and societal challenges, as do the campaigns and initiatives aiming to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding. The social media platform Instagram is being mobilized by individual users to publicly display and share diverse breastfeeding‐related content and to create supportive networks that allow new mothers to share experiences, build confidence, and address challenges related to breastfeeding. Given the widespread use of Instagram globally by diverse sectors of society, this platform could also be used by public health or educational campaigns to promote and “normalize” breastfeeding; however, there is little evidence of this occurring at present. In conclusion, Instagram is currently used by breastfeeding mothers to create supportive networks and could potentially offer new avenues and opportunities to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding more broadly across its large and diverse global online community.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

ARM and MBA designed the study. MB built the program to collect the data and the platform used for analysis. ARM performed the data analysis with some assistance from MB. ARM and MBA collaborated in the drafting, revising, and editing of manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Supporting information

Data S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program and the Children's Hospital Foundation of Manitoba. Dr. Azad holds a Canada Research Chair in the Developmental Origins of Chronic Disease. We acknowledge the Allergy Genes and Environment (AllerGen) Network of Centres of Excellence for catalysing our collaboration on this research endeavour. We thank the coding team of Michelle La, Salina Khan, Parisa Selseleh, and Tracy Parkinson (University of Manitoba) and Jenna Vivian and Corinna Liu (University of Alberta). We also thank Lorena Vehling for her critical review of our manuscript and Instagram users @loothtooth, @mamasmilknochaser, @fitafter, and @tereserohman for permission to share their images. Finally, we acknowledge Robyn‐Hyde Lay, Timothy Caulfield, and Candice Kozak (University of Alberta), who provided guidance and administrative assistance during the project.

Marcon AR, Bieber M, Azad MB. Protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding on Instagram. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12658 10.1111/mcn.12658

REFERENCES

- Alexa (2017). The top 500 sites on the web. Alexa. Retrieved from: https://www.alexa.com/topsites

- Asiodu, I. V. , Waters, C. M. , Dailey, D. E. , Lee, K. A. , & Lyndon, A. (2015). Breastfeeding and use of social media among first‐time African American mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 44(2), 268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2011). 2010 Australian national infant feeding survey: Indicator results. Canberra: AIHW; Retrieved from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420927 [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. M. , & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. (2016). What do women really want? Lessons for breastfeeding promotion. Breastfeeding Medicine. April 2016, 11(3), 102–110. 10.1089/BFm.2015.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. , & Davies, R. (2014). Fathers' experiences of supporting breastfeeding: Challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10(4), 510–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K. (2016). Here's how much celebrities make in the Instagram product placement machine. Jezebel. Retrieved from: https://jezebel.com/heres-how-much-celebrities-make-in-the-instagram-produc-1740632946

- Carah, N. , & Shaul, M. (2016). Brands and Instagram: Point, tap, swipe, glance. Mobile Media & Communication, 4(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Centola, D. (2013). Social media and the science of health behavior. Circulation, 127(21), 2135–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, G. A. , Hill, S. , & Robinson, P. (2011). Using an online service for breastfeeding support: What mothers want to discuss. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 22(2), 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwynar‐Horta, J. (2016). The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. Stream: Inspiring Critical Thought, 8(2), 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva Trammel, J. M. (2017). Breastfeeding campaigns and ethnic disparity in Brazil: The representation of a hegemonic society and quasiperfect experience. Journal of Black Studies, 48(5), 431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Dolski, M. (2016). Toronto club apologizes after sending breastfeeding woman to its basement. Toronto Star. Retrieved from: https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2016/10/17/toronto-club-apologises-after-sending-breastfeeding-woman-to-its-basement.html

- Elo, S. , & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. (2016). “I … don't want to see you flashing your bits around”: Exhibitionism, othering and good motherhood in perceptions of public breastfeeding. Geoforum, 71, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, Y. , & Irurita, V. (2003). Incompatible expectations: The dilemma of breastfeeding mothers. Health Care for Women International, 24(1), 62–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, L. , Miller, M. , & Fletcher, A. (2013). Online healthy lifestyle support in the perinatal period: What do women want and do they use it? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 19(4), 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highfield, T. , & Leaver, T. (2015). A methodology for mapping Instagram hashtags. First Monday, 20(1). Retrieved from: http://firstmonday.org/article/view/5563/4195

- Holcomb, J. (2017). Resisting guilt: Mothers' breastfeeding intentions and formula use. Sociological Focus, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Instagram (2017). 700 million. Instagram Press. Retrieved from: https://instagram-press.com/blog/2017/04/26/700-million/

- Instagram (2018). Community guidelines. Instagram Help. Retrieved from: https://help.instagram.com/477434105621119

- Jin, S. V. , Phua, J. , & Lee, K. M. (2015). Telling stories about breastfeeding through Facebook: The impact of user‐generated content (UGC) on pro‐breastfeeding attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior, 46, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K. M. , Power, M. L. , Queenan, J. T. , & Schulkin, J. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(4), 186–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C. (2015). Lactivism: How feminists and fundamentalists, hippies and yuppies, and physicians and politicians made breastfeeding big business and bad policy. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh, A. L. , Reese, D. D. , Carroll, J. M. , & Rosson, M. B. (2005). Weak ties in networked communities. The Information Society, 21(2), 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Khoday, A. , & Srinivasan, A. (2013). Reclaiming the public space: Breastfeeding rights, protection, and social attitudes. McGill Journal of Law and Health, 7(147). Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2328974 [Google Scholar]

- Koerber, A. (2013). Breast or bottle?: Contemporary controversies in infant‐feeding policy and practice. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kukla, R. (2006). Ethics and ideology in breastfeeding advocacy campaigns. Hypatia, 21(1), 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Labbok, M. (2008). Exploration of guilt among mothers who do not breastfeed: The physician's role. Journal of Human Lactation, 24(1), 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J. R. , & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical kappa‐type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 33, 363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, D. Z. , & Cross, R. (2004). The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Management Science, 50(11), 1477–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, L. (2017). What you need to know about those viral “Tree of Life” breastfeeding photos. POPSUGAR. Retrieved from: https://www.popsugar.com/moms/How-Make-Tree-Life-Breastfeeding-Photo-42870000

- Locatelli, E. (2017). Images of breastfeeding on Instagram: Self‐Representation, publicness, and privacy management. Social Media+ Society, 3(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lup, K. , Trub, L. , & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #instasad?: Exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 18(5), 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, M. (2016). May 24. Canadian social media use and online brand interaction (statistics). Canada's http://internet.com. Retrieved from: http://canadiansinternet.com/2016-canadian-social-media-use-online-brand-interaction-statistics/

- Mejova, Y. , Haddadi, H. , Noulas, A. , & Weber, I. (2015). #foodporn: Obesity patterns in culinary interactions. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Digital Health 2015 (pp. 51‐58). Florence, Italy: ACM.

- Moss, R. (2015). Facebook clarifies nudity policy: Breastfeeding photos are allowed (as long as you can't see any nipples. Huffington post. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/03/16/breastfeeding-facebook-nudity-policy_n_6877208.html

- Niela‐Vilén, H. , Axelin, A. , Melender, H. L. , & Salanterä, S. (2015). Aiming to be a breastfeeding mother in a neonatal intensive care unit and at home: A thematic analysis of peer‐support group discussion in social media. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(4), 712–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEW (2017). Social media fact sheet. Pew Research Center Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

- Rambukkana, N. (2015). Hashtag publics: The power and politics of discursive networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, L. A. , Rempel, J. K. , & Moore, K. C. (2017). Relationships between types of father breastfeeding support and breastfeeding outcomes. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(3). 10.1111/mcn.12337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Group, T. L. B. S. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387(10017), 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumley, J. (2016). April 20. Mother files human rights complaint after being told not to breastfeeding in public. CBC News. Retrieved from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/vaughan-mother-breastfeeding-1.3545634

- Salam, M. (2017). June 9. Why ‘Radical Body Love’ is thriving on Instagram. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/09/style/body-positive-instagram.html

- Sharma, S. S. & De Choudhury, M. (2015). Measuring and characterizing nutritional information of food and ingestion content in Instagram. Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 115‐116). Madrid, Spain: ACM.

- Snowdon, K. (2017). June 8. V&A Museum told to apologize after breastfeeding mother told to ‘cover up’. HuffPost UK. Retrieved from: http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/va-museum-breastfeeding_uk_59874740e4b0cb15b1bf24fb

- Snyder, L. B. (2007). Health communication campaigns and their impact on behavior. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 39(2), S32–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman, N. , & Kellams, A. (2016). Breastfeeding: What are the barriers? Why women struggle to achieve their goals. Journal of Women's Health, 25(7), 714–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista (2018). Number of monthly active Instagram users from January 2013 to September 2017 (in millions). Statista.com Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/

- Statistics Canada (2015). Health at a glance: Breastfeeding rates in Canada. Government of Canada Retrieved from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11879-eng.htm

- Talmazan, Y. (2017). January 17. Husband of Florence Leung releases emotional statement about PPD, pressure to breastfeed. Global news. Retrieved from: https://globalnews.ca/news/3186634/husband-of-florence-leung-releases-emotional-statement-about-ppd-pressure-to-breastfeed/

- Tiggemann, M. , & Zaccardo, M. (2016). ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology, 23, 1–9. Retrieved from: .http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1359105316639436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohrde, O. J. , & Reinke, J. S. (2016). Breastfeeding mothers' use of technology while breastfeeding. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- UK National Health Service . (2012). Infant feeding survey—UK, 2010. NHS digital. Retrieved from: https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB08694

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2012). Breastfeeding report card. Atlanta, GA: US. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm

- US Weekly Staff (2017). Celeb moms share breastfeeding pictures. US Weekly. Retrieved from: https://www.usmagazine.com/celebrity-moms/pictures/celeb-moms-share-breastfeeding-pictures-201458/39771/

- Van Dijk, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. , França, G. V. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Group, T. L. B. S (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterloo, S. F. , Baumgartner, S. E. , Peter, J. , & Valkenburg, P. M. (2017). Norms of online expressions of emotion: Comparing Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media & Society, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2017). Exclusive breastfeeding. WHO website Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1: Supporting Information