Abstract

Breastfeeding benefits mothers and infants. Although immigration in many regions has increased in the last three decades, it is unknown whether immigrant women have better breastfeeding outcomes than non‐immigrants. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta‐analysis to determine whether breastfeeding rates differ between immigrant and non‐immigrant women. We searched Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Google Scholar, 1950 to 2016. We included peer‐reviewed cross‐sectional and cohort studies of women aged ≥16 years that assessed and compared breastfeeding rates in immigrant and non‐immigrant women. Two independent reviewers extracted data using predefined standard procedures. The analysis included 29 studies representing 1,539,659 women from 14 countries. Immigrant women were more likely than non‐immigrants to initiate any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding (pooled adjusted prevalence ratio 1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.19; 11 studies). Exclusive breastfeeding initiation was higher but borderline significant (adjusted prevalence ratio 1.20, 95% CI 1.00–1.45; 5 studies, p = 0.056). Immigrant women were more likely than non‐immigrants to continue any breastfeeding between 12‐ and 24‐week postpartum (pooled adjusted risk ratio 2.04, 95% CI 1.79–2.32; 3 studies) and > 24 weeks (adjusted risk ratio 1.33, 95% CI 1.02–1.73; 6 studies) but not exclusive breastfeeding. Immigrant women are more likely than non‐immigrants to initiate and maintain any breastfeeding, but exclusive breastfeeding remains a challenge for both immigrants and non‐immigrants. Social and cultural factors need to be considered to understand the extent to which immigrant status is an independent predictor of positive breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: breastfeeding, immigrant, meta‐analysis, non‐immigrant

Key messages.

This meta‐analysis evaluated how breastfeeding differs between immigrants and non‐immigrants.

Immigrant women are more likely to initiate breastfeeding and do so longer, but not exclusively.

Social and cultural factors need to be further considered to understand the extent to which immigrant status is an independent predictor of positive breastfeeding practices.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding is promoted worldwide as the ideal method for infant feeding by the World Health Organization (WHO; World Health Organization, 2011), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2016), the American Academy of Paediatrics (Eidelman & Schanler, 2012) and numerous other international associations. Over 800,000 under five child deaths a year could be prevented globally if optimal breastfeeding practices were achieved as recommended by the WHO and United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF). These recommendations include initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, and continued breastfeeding for 2 or more years, as well as adequate complementary feeding starting at 6 months (World Health Organization, 2003).

The benefits of breastfeeding are well established and ever growing and impact both maternal and infant health outcomes. Breastfeeding not only leads to improved cognitive development among children but also learning and educational attainment, productivity and wages. Given these outcomes, it is not surprising; the benefits of breastfeeding also extend to society as a whole where it has been estimated that for every $1 invested in breastfeeding $35 is generated in economic returns (Thousand Days, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund [UNICEF], & WHO, 2017; Weimer, 2001). Other investment cases show that in five of the world's largest emerging economies—China, India, Indonesia, Mexico and Nigeria—the lack of investment in breastfeeding results in an estimated 236,000 child deaths per year and US$119 billion in economic losses (Thousand Days, UNICEF, & WHO, 2017, 2017).

Globally, the immigrant population—people who were born in one country and moved to another—has grown considerably in the last three decades. For example, the number of immigrants living in the United States has increased from 31.1 million in 2000 to 40.7 million in 2012, accounting for 13% of the total population (Brown & Patten, 2014), and in Canada and Australia, immigrants represent one in five and one in four residents, respectively (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016; Statistics Canada, 2015). Importantly, more than half of immigrants are women and most are in their childbearing years. This clearly suggests that immigrant women from diverse cultures are a rapidly growing maternal population and will have significant need for perinatal services (Statistics Canada, 2017).

As with most major life transitions, the perinatal period is steeped with rich cultural practices. In many traditional cultures, women's behaviours are often restricted following childbirth and specific rituals are observed in order to prevent ill health in later years. In these “ethnokinship” cultures (e.g., many cultures of East Asia, South Asia and the Middle East), the practice of traditional rituals emphasizes social support for a protracted postpartum period (Posmontier & Horowitz, 2004). Although modern technology may still be integrated into these cultures, social relationships are viewed to be of primary importance, and as such, postpartum rituals often extend beyond the immediate postpartum period to 30–40 days following childbirth. Postpartum traditional rituals frequently includes enhanced maternal rest, organized support from extended family and dietary recommendations (Dennis et al., 2007; Singh, Kogan, & Dee, 2007). This is in contrast to Western or “modern” cultures where postpartum care primarily focuses on the immediate physical health of mothers and their infants through the use of technological interventions (Posmontier & Horowitz, 2004). Subsequently, postpartum rituals in “technocentric” cultures (e.g., Canada, the United States, United Kingdom and many parts of Europe, Australia and New Zealand) do not typically extend beyond the first few days following childbirth. These diverse postpartum practices may significantly influence maternal behaviours including infant feeding.

Disparities in breastfeeding rates have been reported between immigrant and non‐immigrant women, often varying by nativity, length of stay in the host country and acculturation. Women who migrate tend to maintain the breastfeeding behaviours of their country of origin for a period of time, with some studies from the United States, Canada and some European countries suggesting that women with a shorter duration of stay in the new host country and with stronger ties to their country of origin have higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration than women born in the host country (Dennis, Gagnon, Van Hulst, & Dougherty, 2014; Dennis, Gagnon, Van Hulst, Dougherty, & Wahoush, 2013; Harley, Stamm, & Eskenazi, 2007; Hendrick & Potter, 2017; Singh et al., 2007). Conversely, other studies have indicated poorer breastfeeding outcomes among immigrant women compared with non‐immigrants (Homer, Sheehan, & Cooke, 2002; McLachlan & Forster, 2006; Rio, Castello‐Pastor, Del Val, et al., 2011; Rossiter & Yam, 2000). The extent of the effect of immigrant status on breastfeeding rates is still largely undecided. Maternal and child health care providers, who see women regularly during the postpartum period, are optimally situated to encourage women to meet their breastfeeding goals. However, without having a clear understanding of the differences in breastfeeding rates between immigrant and non‐immigrant women health care providers are unable to target their care effectively to ensure optimal infant feeding practices among the diverse cultures (Feldman‐Winter, Schanler, O'Connor, & Lawrence, 2008). Understanding breastfeeding rates among immigrant and non‐immigrant women can also lead to further investigations to inform whether differences observed are related to cultural‐bounded postpartum practices. Thus, it is clinically important to systematically examine breastfeeding rates in relation to immigration status to promote policies and inform evidence‐based clinical interventions to increase overall breastfeeding rates across diverse cultures. The purpose of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to determine whether breastfeeding initiation, duration and exclusivity rates differed between immigrant and non‐immigrant women.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009), we conducted a systematic review of the literature in Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Google Scholar from 1950 until September 2016. Predefined key terms were as follows: [breast feeding OR breastfeeding OR human milk OR breast milk OR bottle feeding OR bottle feeding] AND [immigration OR immigrant OR immigra* OR refugee OR asylum OR country of birth OR emigration OR foreigner OR language]. We used medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and text words in Medline and Emtree terms and text words in Embase. See Table S1 in the supporting information for the full search strategy in Medline. We screened the titles and abstracts of all citations identified from this search for relevance. If an article was potentially relevant, we then assessed the full text for eligibility. Further, we manually searched the reference lists of all eligible articles for additional titles not returned in the initial search.

2.2. Study eligibility

We included studies if they (1) reported the results of peer‐reviewed research based on cross‐sectional and cohort study designs, (2) included women 16 years of age or older, (3) assessed breastfeeding rates in both immigrant and non‐immigrant women and (4) provided data to compare breastfeeding rates between immigrant and non‐immigrant women (e.g., prevalence ratios [PR], odds ratios [OR] or risk ratios [RR] and their associated 95% confidence intervals [CI]). We excluded studies if they (1) were conducted among self‐selected volunteers (because self‐selected volunteers are generally healthier than the wider population and their results are likely not representative of all women; Leung, McDonald, Kaplan, Giesbrecht, & Tough, 2013); (2) recruited women from two different countries (i.e., immigrant and non‐immigrant women did not live in the same country); (3) reported results for only a subsample of a study population; or (4) did not report sufficient results to estimate a PR, OR or RR.

2.3. Data extraction

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers [KFH and RS] based on pre‐determined criteria. We extracted year of publication, study design, study population, sample size, breastfeeding outcomes, time period of assessment, prevalence of breastfeeding in immigrant and non‐immigrant women, an estimate of breastfeeding comparing immigrant and non‐immigrant women (i.e., PR, OR or RR) and whether or not this estimate was adjusted for covariates. For studies that reported more than one estimate, we extracted maximally adjusted estimate. Breastfeeding outcomes were (1) rate of initiation of any breastfeeding, (2) rate of exclusive breastfeeding and (3) breastfeeding duration. As per Labbok and Krasovec's criteria, exclusive breastfeeding was defined as infant feeding with only breastmilk and no other liquids or solids (even water), and partial breastfeeding was defined as breastfeeding in addition to the use of artificial feeds, including milk, cereal or other food (Labbok & Krasovec, 1990). The reviewers discussed disagreements in data extraction until consensus was reached.

2.4. Quality assessment

Two reviewers [KFH and RS] rated the risk of bias of each study independently using criteria adapted from the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (Armijo‐Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo, & Cummings, 2012). Studies were rated as having low, moderate or high risk of bias on selection bias (i.e., response rate and representativeness of the sample), detection bias (i.e., validity and reliability of the outcome measures), confounding and attrition bias (i.e., loss to follow‐up and missing data). The reviewers discussed disagreements in quality ratings until consensus was reached.

2.5. Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analyses of (1) rates and duration of exclusive breastfeeding and (2) rates and duration of any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding. Some studies reported an odds ratio for difference in duration of breastfeeding between immigrant and non‐immigrant women or reported proportions of immigrant and non‐immigrant women continuing breastfeeding at a certain postpartum period. In order to include all studies on duration of breastfeeding in the meta‐analyses, for studies reporting mean duration of breastfeeding, we calculated the standardized mean difference by dividing the difference between the two means by their pooled standard deviation. For a single study reporting mean duration of breastfeeding for two subgroups of immigrant women (Verga, Widmeier‐Pasche, Beck‐Popovic, Pauchard, & Gehri, 2014), we combined means and standard deviations of two means into a single estimate using a formula described by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2011). We converted the standardized mean difference into an OR using the logit method (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) and subsequently converted the OR to a PR or RR as appropriate, because ORs are not good estimates of relative risks for common outcomes such as breastfeeding (McNutt, Wu, Xue, & Hafner, 2003). We converted the OR to a PR or RR using the prevalence of the outcome in non‐immigrant women (control group).

We used a random‐effects meta‐analysis to combine the estimates of different studies (Higgins & Green, 2011) and assessed analyses for heterogeneity across studies using the I 2 statistic (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). An I 2 statistic <25% indicated small inconsistency, and an I 2 statistic >50% indicated large inconsistency (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). We used meta‐regression to assess differences between subgroups (Higgins & Green, 2011). We performed subgroup analyses according to adjustment for confounding, selection bias and attrition bias. We assessed publication bias using a funnel plot and the Egger test (Higgins & Green, 2011). An asymmetrical funnel plot and statistically significant Egger test suggest the presence of publication bias (Higgins & Green, 2011). We used the trim and fill method to determine the potential number of missing studies due to publication bias and to adjust the pooled estimates for small study effects (Duval & Tweedie, 2000; Rothstein, Sutton, & Borenstein, 2005). We used Stata v. 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) for meta‐analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

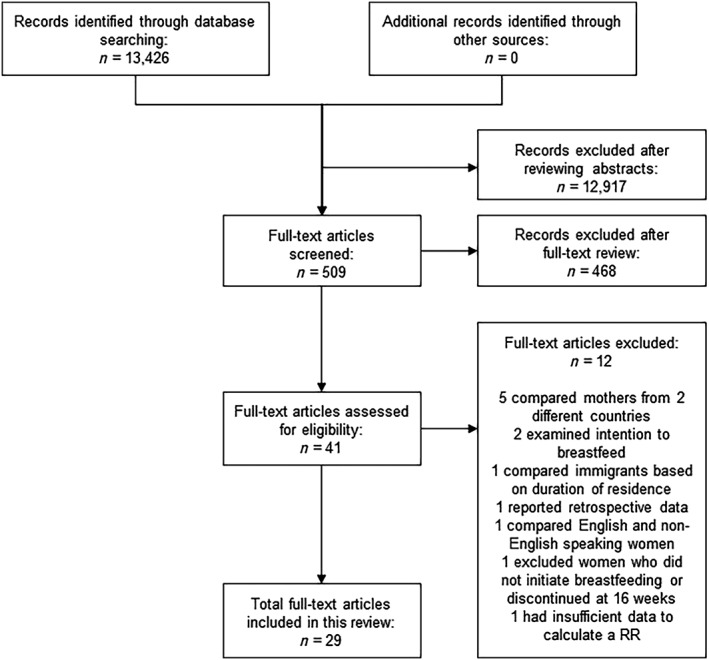

We identified 13,426 publications, of which 41 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of the 41 studies, we excluded 12 studies upon full‐text review: (1) five studies compared women from two different countries (Noor & Rousham, 2008; Kocturk, 1988; Utaka et al., 2005; Rubin, Nir‐Inbar & Rishpon, 2005–2006; Chen, Binns, Zhao, Maycock, & Liu, 2013), (2) two studies reported only on intention to breastfeed and not on rates of breastfeeding initiation or duration (Bonuck, Freeman, & Trombley, 2005; Lee et al., 2005), (3) one study compared immigrant Mexicans based on their duration of residence in the United States (Harley et al., 2007), (4) one study used only retrospective data reported when children were 0 to 5 years of age (Roville‐Sausse, 2005), (5) one study compared English speaking with non‐English speaking women (Homer et al., 2002), (6) one study excluded women who did not initiate breastfeeding or were no longer breastfeeding at 16‐week postpartum (Dennis et al., 2014), and (7) one study provided insufficient data to estimate a RR (Lee, Elo, McCollum, & Culhane, 2009). Therefore, 29 studies incorporating data from 1,539,659 women were included in the meta‐analyses.

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart

3.2. Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 29 studies are in Table 1. Twenty‐eight studies were published between 2001 and 2016; one was published in 1978 (Drew et al., 1978). Nine studies had cohort designs, (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; Hawkins et al., 2008; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; Sussner et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015) and 20 were cross‐sectional (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; De Amici et al., 2001; Drew et al., 1978; Farchi et al., 2016; Forster et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 2014; Kornosky et al., 2008; Ladewig et al., 2014; McLachlan & Forster, 2006; Merten et al., 2007; Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Oakley et al., 2014; Philipp et al., 2001; Rio et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Vanderlinden, Levecque, & Van Rossem, 2015; Verga et al., 2014; Zuppa et al., 2010). Eight studies were conducted in the United States (Hawkins et al., 2014; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kornosky et al., 2008; Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Philipp et al., 2001; Singh et al., 2007; Sussner et al., 2008; Vanderlinden et al., 2015) four in Australia (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Drew et al., 1978; Forster et al., 2006; McLachlan & Forster, 2006), three in Italy (De Amici et al., 2001; Farchi et al., 2016; Zuppa et al., 2010) two each in Switzerland (Oakley et al., 2014; Verga et al., 2014), Taiwan (Kuo et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2015) and the United Kingdom (Hawkins et al., 2008; Oakley et al., 2014) and one each in Denmark (Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014), Greece (Tavoulari et al., 2015), Hong Kong (Kwok et al., 2013), Ireland (Ladewig et al., 2014), Netherlands (Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008), Sweden (Besharat Pour et al., 2016), Spain (Rio et al., 2011) and the United Arab Emirates (Al Tajir et al., 2006). Sample sizes ranged from 141 to 1,067,375 women, with most studies including more than 1,000 women (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; Farchi et al., 2016; Hawkins et al., 2008; Hawkins et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; Ladewig et al., 2014; Merten et al., 2007; Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Oakley et al., 2014; Rio et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Vanderlinden et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015; Zuppa et al., 2010). Twenty‐two studies measured any breastfeeding initiation (Al Tajir et al., 2006; De Amici et al., 2001; Drew et al., 1978; Farchi et al., 2016; Hawkins et al., 2008; Hawkins et al., 2014; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kornosky et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; Ladewig et al., 2014; McLachlan & Forster, 2006; Merten et al., 2007; Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Oakley et al., 2014; Philipp et al., 2001; Rio et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Sussner et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015; Zuppa et al., 2010), eight studies measured rates of exclusive breastfeeding (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; Kwok et al., 2013; Merten et al., 2007; Vanderlinden et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015) and 15 studies measured breastfeeding duration (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; Forster et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 2008; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; Ladewig et al., 2014; Oakley et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2007; Sussner et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Verga et al., 2014). Breastfeeding was measured at birth in 13 studies (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; De Amici et al., 2001; Drew et al., 1978; Farchi et al., 2016; Hawkins et al., 2014; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; McLachlan & Forster, 2006; Merten et al., 2007; Oakley et al., 2014; Philipp et al., 2001; Rio et al., 2011; Sussner et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Zuppa et al., 2010) and at 4 (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Kuo et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015), 6 (Oakley et al., 2014; Sussner et al., 2008) eight (Tavoulari et al., 2015), 12 (Kwok et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2007; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Vanderlinden et al., 2015), 16 (Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008; Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015), 20 (Tavoulari et al., 2015), 24 (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Forster et al., 2006; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kuo et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2007; Sussner et al., 2008; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015), 36 (Kwok et al., 2013; Ladewig et al., 2014) and 52 weeks (Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2007; Verga et al., 2014) in the remaining studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year, country | Study design | Study population | Sample size in analysis | Outcome | Timing | Adjustment for confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Amici, Gasparoni, Guala, and Klersy (2001), Italy67 | Cross‐sectional | Women admitted to OB wards in two hospitals in northern Italy | 269 I = 167 (50 Arabs, 43 Africans, 74 Eastern Europeans) NI = 102 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: education, smoking during pregnancy |

| Al Tajir, Sulieman, and Badrinath (2006), United Arab Emirates49 | Cohort | Women who delivered at Al Qassimi Hospital in Sharjeh | 221 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: age, parity, education, labour analgesia, number of days in hospital, discharged on day 1 BF, in labour room |

| I = ? | Duration | 4 weeks | ||||

| NI = ? | Exclusivity | 24 weeks | ||||

| Bandyopadhyay, Small, Watson, and Brown (2010), Australia62 | Cross‐sectional | Women in 16 participating local government areas in Victoria | 10,440 | Duration | 24 weeks | Adjusted: local government area |

| I = 644 | ||||||

| NI = 9,796 | ||||||

| Besharat Pour et al. (2016), Sweden57 | Cross‐sectional | Infants, 2 months, born February 1994 to November 1966 in Stockholm | 2,278 | Duration exclusivity | 24 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 299 | ||||||

| NI = 1,979 | ||||||

| Bulk‐Bunschoten, Pasker‐de Jong, van Wouwe, and de Groot (2008), Netherlands56 | Cohort | Infants <4 months receiving first standard care at 115 well‐baby clinics | 4,438 | Duration | Birth | Adjusted: maternal age, parity, education, degree of urbanization |

| I = 421 (Turkish, Moroccan, other) | Exclusivity | 16 weeks | ||||

| NI = 3,861 | ||||||

| Busck‐Rasmussen, Villadsen, Norsker, Mortensen, and Andersen (2014), Denmark61 | Cross‐sectional | Infants with at 1+ health visit in 18 areas of Copenhagen | 28,441 | Exclusivity | 16+ weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 3,599 | ||||||

| NI = 24,842 | ||||||

| Drew, Barrie, Horacek, and Kitchen (1978), Australia47 | Cross‐sectional | Consecutive immigrant Greek and sample of Anglo‐Saxon Australian infants, Melbourne | 1,107 | Initiation | Birth | Unadjusted |

| I = 887 | ||||||

| NI = 220 | ||||||

| Farchi, Asole, Chapin, and Di Lallo (2016), Italy65 | Cross‐sectional | Eight hospitals in Rome, six outside | 6,497 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: age, parity, mode of delivery |

| I = 1,220 | ||||||

| NI (98%) or from developed countries = 5,277 | ||||||

| Forster, McLachlan, and Lumley (2006), Australia69 | Cross‐sectional | Sample of women who attended public, tertiary and women's hospital in Melbourne | 972 | Duration | 24 weeks | Adjusted: age, BMI, relationship problems, smoking, childbirth education, breastfed as a baby, desire to breastfeed, formula in hospital |

| I = 229 | ||||||

| NI = 535 | ||||||

| Hawkins, Lamb, Cole, and Law (2008), United Kingdom50 | Cohort | Population‐based sample of infants born September 2000 to January 2002 | 8,588 | Initiation duration | 16 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 2,110 | ||||||

| NI = 6,478 | ||||||

| Hawkins, Gillman, Shafer, and Cohen (2014), United States60 | Cross‐sectional | Live births in MA, from Registry of Vital Records and Statistics, 1996–2009 | 1,067,375 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: age, parity, marital status, education, plurality, prenatal care, source of payment, mode of delivery, year of birth |

| I =? | ||||||

| NI =? | ||||||

| Kimbro, Lynch, and McLanahan (2008), United States48 | Cohort | 75 hospitals in 20 cities in 15 states | 3,627 I = 302 Mexico NI = 934 white, 2,043 black, 348 Mexican‐American | Initiation duration | Birth 24 weeks | Unadjusted |

| Kornosky, Peck, Sweeney, Adelson, and Schantz (2008), United States63 | Cross‐sectional | Sample of Hmong households recruited through Southeast Community centre and Hmong Association in Green Bay | 141 | Initiation | ? | Unadjusted |

| I =? | ||||||

| NI =? | ||||||

| Kuo et al. (2008), Taiwan52 | Cohort | Sample of mothers who gave birth in 2003 from birth registration at Department of Health | 9,103 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: age, ethnicity, income, job, education, area of residence, family support, delivery method |

| I = 1,354 | Duration | 4 weeks | ||||

| NI = 7,749 | 16 weeks | |||||

| 24 weeks | ||||||

| Kwok, Leung, and Schooling (2013), Hong Kong51 | Cohort | Population‐based sample of women who gave birth in Hong Kong, April and May 1997 | 7,534 | Initiation | Birth | Unadjusted |

| I = 2,910 | Duration | 12 weeks | ||||

| NI = 4,624 | Exclusivity | 36 weeks | ||||

| Ladewig, Hayes, Browne, Layte, and Reulbach (2014), Ireland71 | Cross‐sectional | Sample of infants randomly selected from Child Benefit Register maintained by Department of Social Protection | 11,092 | Initiation | 36 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 2,363 | Duration | |||||

| NI = 8,629 | ||||||

| McLachlan and Forster (2006), Australia24 | Cross‐sectional | Women who gave birth in a large public, tertiary referral maternity Hospital in Melbourne | 300 I = 200 (100 Turkish, 100 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: Education, ability to understand English |

| Merten, Wyss, and Ackermann‐Liebrich (2007), Switzerland66 | Cross‐sectional | Random sub‐sample from routinely collected data in Swiss Baby‐Friendly health facilities | 34,090 | Initiation | Birth | Adjusted: Age, parity child sex, birth weight, preterm delivery, multiple birth, transfer to ICU, health facility, place of delivery |

| I = 26,843 | Exclusive | |||||

| NI = 7,247 | Initiation | |||||

| Neault (2007), United States70 | Cross‐sectional | Sample of Children's Sentinel Nutrition Assessment Program in emergency departments and clinics to coincide with peak patient flow times in six U.S. cities | 8,800 | Initiation | 52 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 3,592 | ||||||

| NI = 5,208 | ||||||

| Oakley, Henderson, Redshaw, and Quigley (2014), United Kingdom68 | Cross‐sectional | Random sample of women who gave birth in 2009, identified by Office for National Statistics using registration data | 4,637 | Initiation duration | Birth 6 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 969 | ||||||

| NI = 3,668 | ||||||

| Vietnamese) NI = 100 | ||||||

| Philipp et al. (2001), United States59 | Cross‐sectional | Medical records of infants admitted to newborn services, Boston Medical Centre | 309 | Initiation | Birth | Unadjusted |

| I = 164 | ||||||

| NI = 145 | ||||||

| Rio et al. (2011), Spain22 | Cross‐sectional | Registry records in two regions | 234,459 | Initiation | Birth | Unadjusted |

| I = 42,520 | ||||||

| NI = 191,939 | ||||||

| Singh et al. (2007), United States17 | Cross‐sectional | Random‐digit‐dial sample from all states; one child randomly selected from each household | 31,057 | Initiation | 12 weeks | Unadjusted |

| Duration | 24 weeks | |||||

| 52 weeks | ||||||

| I = 2,992 | ||||||

| NI = 28,065 | ||||||

| Sussner, Lindsay, and Peterson (2008), United States54 | Cohort | Sample of two urban areas in north‐east | 679 | Initiation duration | Birth, ≥6‐ < 24 weeks 24 + weeks | Adjusted: age, education, no. of children, BMI, language acculturation, years in US, depression, smoking, # people in house |

| I = 373 | ||||||

| NI = 306 | ||||||

| Tavoulari, Benetou, Vlastarakos, Kreatsas, and Linos (2015), Greece55 | Cohort | Women recruited in maternity ward of tertiary hospital | 428 | Initiation duration | Birth every 4 weeks until 24 weeks | Adjusted: age, BMI, employment status, socio‐demographic factors, medical conditions, lactation factors |

| I = 124 | ||||||

| NI = 304 | ||||||

| Vanderlinden (2015), United States58 | Cross‐sectional | Random sample of infants born in 2004 | 34,314 | Exclusivity | 12 weeks | Adjusted: parity, poverty, country of origin, infant sex, birth weight, birth height |

| I = 5,184 | ||||||

| NI = 34,314 | ||||||

| Verga et al. (2014), Switzerland31 | Cross‐sectional | Residents of Lausan recruited at health visits by 3 family doctors and Children's Hospital of Lausanne | 463 | Duration | 52 weeks | Unadjusted |

| I = 182 (92 < 5 yrs, 91 5–10 yrs) | ||||||

| NI = 257 | ||||||

| Wu, Wu, and Chiang (2015), Taiwan53 | Cohort | Nationally representative sample | 21,217 I = 2,794 (955 China, 1,839 SE Asia) NI = 18,416 | “Almost” exclusivity initiation duration | 16 weeks | Adjusted: residential area, parental age, job status, age of the mother, infant sex |

| 24 weeks | ||||||

| Zuppa et al. (2010), Italy64 | Cross‐sectional | Infants born in 2005 at Agostino Gemelli Hospital in Rome | 2,465 | Initiation | Birth | Unadjusted |

| I = 473 | ||||||

| NI = 1,990 |

Note. BMI: body mass index; I: immigrant; ICU: intensive care unit; NI: non‐immigrant.

3.3. Study quality

Most studies had low or moderate risk of selection bias. However, six studies had high risk of selection bias due to recruiting a convenience sample or having a response rate less than 60% (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Forster et al., 2006; Oakley et al., 2014; Tavoulari et al., 2015; Verga et al., 2014). Most studies also had low or moderate risk of detection bias. One study was categorized as having high risk of detection bias due to asking about exclusive breastfeeding initiation more than 3 months after birth (Vanderlinden et al., 2015). Fifteen studies had high risk of confounding because they did not control for any confounders (Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; Drew et al., 1978; Hawkins et al., 2008; Kimbro et al., 2008; Kornosky et al., 2008; Kwok et al., 2013; Ladewig et al., 2014; Neault, Frank, Merewood et al., 2007; Oakley et al., 2014; Philipp et al., 2001; Rio et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Verga et al., 2014). All studies had low or moderate risk of attrition bias except for two studies that had high risk (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Sussner et al., 2008; Table S2).

3.4. Differences in breastfeeding between immigrant and non‐immigrant women

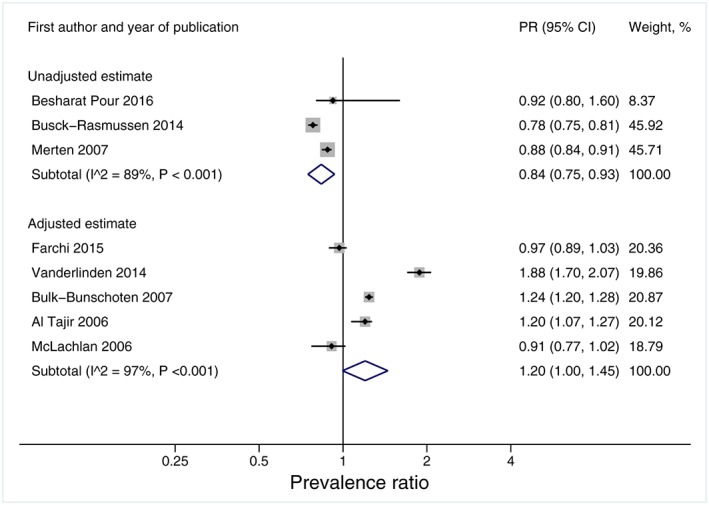

3.4.1. Exclusive breastfeeding initiation and duration

Results of individual studies of exclusive breastfeeding initiation and duration are reported in Table S2. The pooled unadjusted PR of exclusive breastfeeding initiation among immigrant women compared with non‐immigrants was 0.84 (95% CI 0.75–0.93, I 2 = 89%, 3 studies, N = 64,809 women), whereas the pooled adjusted PR for studies that controlled their estimates for confounding was 1.20 (95% CI 1.00–1.45 [p = 0.056], I 2 = 97%, 5 studies, N = 50,954; Figure 2). Of the eight studies that examined exclusive breastfeeding, three reported duration of exclusive breastfeeding for immigrant vs. non‐immigrant women (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Besharat Pour et al., 2016; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008) resulting in a pooled unadjusted RR of 1.19 (95% CI 0.83–1.71, I 2 = 95%, N = 6,859). Two (Al Tajir et al., 2006; Bulk‐Bunschoten et al., 2008) adjusted their estimates for some confounding factors, resulting in a pooled RR of 1.33 (95% CI 0.92–1.93, I 2 = 89%, N = 4,659).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of exclusive breastfeeding initiation rates in immigrants vs. non‐immigrants. The grey boxes represent weights given to each study. The horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The open diamonds represent the subgroup and overall pooled estimates. The I 2 and P values for heterogeneity are shown

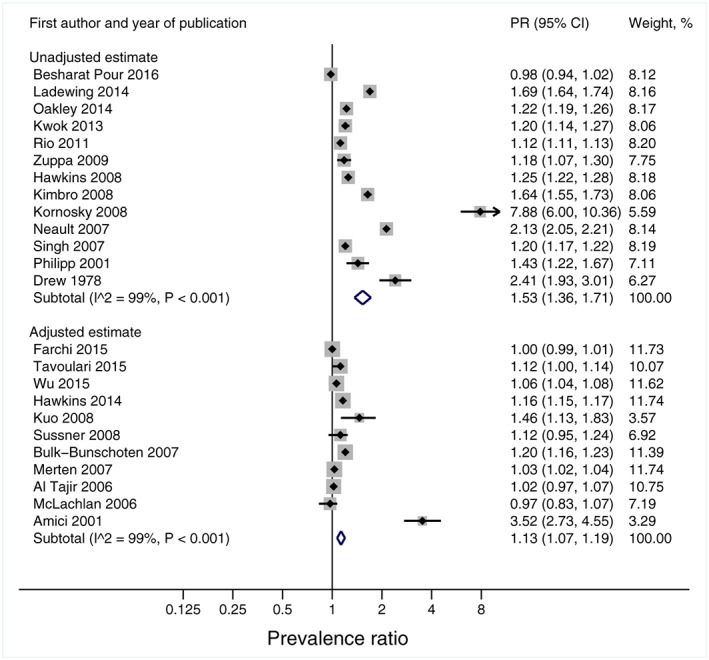

3.4.2. Any breastfeeding initiation and duration

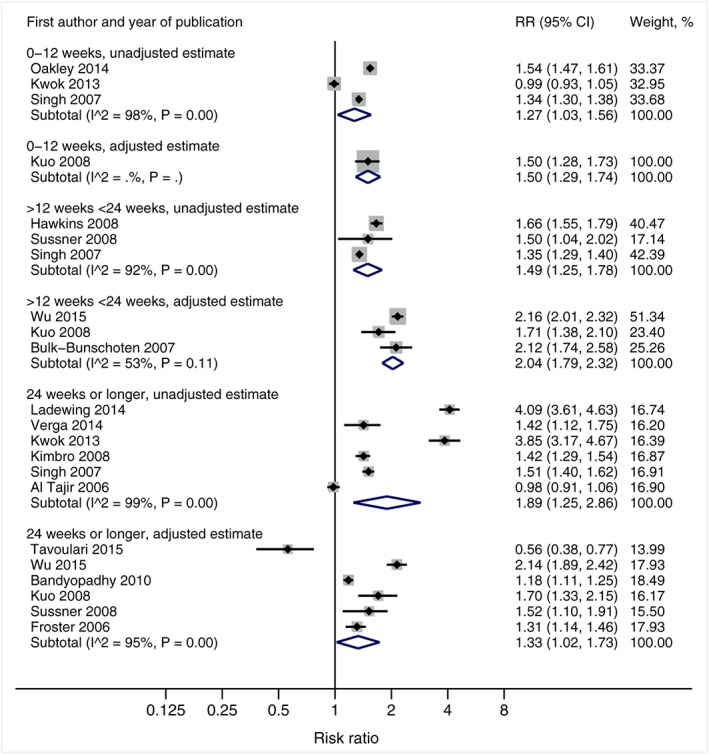

Results of individual studies of any breastfeeding initiation and duration, including exclusive or partial breastfeeding, are reported in Table S2. The pooled unadjusted PR of the initiation of any breastfeeding among immigrant women compared with non‐immigrants was 1.53 (95% CI 1.36–1.71, I 2 = 99%, 13 studies, N = 315,872), whereas the pooled adjusted PR for studies that controlled their estimates for confounding was 1.13 (95% CI 1.07–1.19, I 2 = 99%, 11 studies, N = 1,177,242; Figure 3). Immigrant women were more likely to continue any breastfeeding than non‐immigrant women. The pooled adjusted RRs were 2.04 (95% CI 1.79–2.32, 3 studies, N = 34,758) for any breastfeeding for >12 and <24 weeks and 1.33 (95% CI 1.02–1.73, 6 studies, N = 42,196) for any breastfeeding for 24 weeks or longer (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of initiation rates of partial or exclusive breastfeeding in immigrants vs. non‐immigrants. The grey boxes represent weights given to each study. The horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The open diamonds represent the subgroup and overall pooled estimates. The I 2 and P values for heterogeneity are shown

Figure 4.

Forest plot of any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding duration in immigrants vs. non‐immigrants. The grey boxes represent weights given to each study. The horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The open diamonds represent the subgroup and overall pooled estimates. The I 2 and P values for heterogeneity are shown

3.5. Publication bias

The p‐value for the Egger test for the eight studies on initiation of exclusive breastfeeding was 0.73 (data not shown). The test was not performed for duration of exclusive breastfeeding due to the small number of studies. A funnel plot of the 24 studies on initiation of any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding was asymmetrical (Egger test p = 0.02; Figure S1). Including only studies that controlled estimates for confounders, the Egger test for 11 studies on initiation of any breastfeeding was non‐significant (p = 0.59, Figure S2). Moreover, the Egger test was non‐significant for the 12 studies on the duration of any breastfeeding (p = 0.28; Figure S3).

3.6. Sensitivity analyses

The pooled PR of all eight studies on initiation of exclusive breastfeeding was 1.06 (95% CI 0.88–1.28), and the trim and fill method imputed no missing studies. There were not enough studies that examined duration of exclusive breastfeeding to impute missing studies.

The pooled PR of all 24 studies on initiation of any breastfeeding was 1.33 (95% CI 1.25–1.41), and the trim and fill method imputed eight missing studies, reducing the pooled estimate to 1.10 (95% CI 1.03–1.18) after adjustment for small study effects. For the 11 studies on initiation of any breastfeeding that controlled their estimates for some confounders, the trim and fill method imputed two missing studies; the pooled PR reduced to 1.07 (95% CI 1.02–1.14) after adjustment for small study effects. The pooled RR of all four studies on duration of any breastfeeding for ≤12 weeks was 1.32 (95% CI 1.10–1.57), and the trim and fill method imputed one missing study, reducing the pooled estimate to 1.26 (95% CI 1.06–1.48) after adjustment for small study effects. The pooled RR of all six studies on duration of any breastfeeding for >12 and <24 weeks was 1.73 (95% CI 1.41–2.12); the trim and fill method imputed three missing studies, reducing the pooled estimate to 1.45 (95% CI 1.18–1.77) after adjustment for small study effects. Finally, the pooled RR of all 12 studies on duration of any breastfeeding for ≥24 weeks was 1.58 (95% CI 1.25–2.01); the trim and fill method imputed three missing studies, reducing the pooled estimate to 1.24 (95% CI 0.94–1.65) after adjustment for small study effects. For the six studies of any breastfeeding for ≥24 weeks that controlled their estimates for some confounders, the trim and fill method imputed one missing study; the pooled estimate reduced to 1.20 (95% CI 0.89–1.61) after adjustment for small study effects.

When evaluating the impact of bias on statistically significant meta‐analysis results, the difference between immigrant and non‐immigrant women in the duration of any breastfeeding was larger after excluding studies with high risk of selection bias. We assessed 5 of the 12 studies on duration of any breastfeeding for ≥24 weeks as having high risk of selection bias. A meta‐analysis of these five studies showed no difference between immigrant and non‐immigrant women (pooled RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.93–1.29, I 2 = 90%). The difference between immigrant and non‐immigrant women in the duration of any breastfeeding was independent of attrition bias.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta‐analysis of 29 studies representing 1,539,659 women in 14 countries found only a small difference between immigrant and non‐immigrant women in the initiation of any breastfeeding or exclusive breastfeeding. Immigrant women were twice as likely as non‐immigrants to continue any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding to 12‐ to 24‐weeks postpartum and were 33% more likely to breastfeed beyond 6 months. The findings were slightly attenuated but remained robust after adjusting for publication bias, and differences in duration of any breastfeeding between immigrants and non‐immigrants were even stronger after excluding studies with high risk of selection bias. These results have implications for the development of universal and targeted programs aimed at improving breastfeeding rates. The results of this review suggest that both immigrant and non‐immigrant women have poor exclusive breastfeeding rates; a finding consistent with the Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, which evaluated 194 nations, found that only 40% of infants younger than 6 months were breastfed exclusively and only 23 countries had exclusive breastfeeding rates above 60% (UNICEF, 2017). Future breastfeeding interventions internationally should target strategies to promote and support exclusively breastfeeding to 6‐month postpartum as recommended by WHO; strategies to promote extended breastfeeding up to 2 years postpartum and beyond are also encouraged to maximize health and economic benefits.

Our lack of finding any important difference in breastfeeding initiation rates between immigrant and non‐immigrant women is inconsistent with the common belief that immigrant women are more likely to initiate breastfeeding than women born in the host country (Dennis et al., 2014; Harley et al., 2007; Hendrick & Potter, 2017; Singh et al., 2007). There may be are several reasons for our finding. First, previous studies estimated ORs to compare the initiation of breastfeeding between immigrant and non‐immigrant women. Breastfeeding is common, and ORs are known to overestimate differences in risk when the prevalence of the outcome of interest is higher than 10% (McNutt et al., 2003), thereby potentially exaggerating the size of the difference between immigrant and non‐immigrant women. In the present meta‐analysis, we converted ORs to prevalence ratios or risk ratios to avoid this issue. Second, many previous studies did not control their analyses for confounding. In the current meta‐analysis, we conducted additional analyses limiting our meta‐analysis to studies that controlled their estimates for at least some confounding factors. The pooled estimate of these studies indicated that initiation of exclusive breastfeeding was only 20% higher in immigrant women than in non‐immigrants. Further, the difference in initiation of any breastfeeding between immigrant and non‐immigrant women largely attenuated after limiting the meta‐analysis to studies that controlled for confounding.

Our finding that immigrant women were more likely to continue any breastfeeding to 12‐weeks postpartum or longer is consistent with some prior literature (Hendrick & Potter, 2017; Singh et al., 2007) but not all (Busck‐Rasmussen et al., 2014; Groleau, Souliere, & Kirmayer, 2006; Harley et al., 2007; Sussner et al., 2008). Heterogeneity across studies may be explained by different countries of origin, diverse traditional postpartum rituals and cultural practices, and varying duration in the host country. For example, Gibson‐Davis and Brooks‐Gunn (Gibson‐Davis & Brooks‐Gunn, 2006) showed that with each additional year of residency in the United States, the odds of breastfeeding decreased by 4%. This decline may be explained by greater acculturation, which describes the process of adjusting to a new culture (Ahluwalia, D'Angelo, Morrow, & McDonald, 2012). Further research is needed to understand the factors that predict breastfeeding among immigrant women. Some studies have suggested that predictive factors differ between immigrants and non‐immigrants. A Canadian study showed that in immigrant women factors associated with breastfeeding exclusivity at 16‐week postpartum were older maternal age, non‐refugee immigrant or asylum‐seeking status, feeling most comfortable in the country of origin and a higher Gender Development Index (a measure of gender equality) in the country of origin. In contrast, in non‐immigrants predictors were marital status, neonatal health and maternal mental health. The only similar risk factor between the two groups was breastfeeding status at 1‐week postpartum (Dennis et al., 2014). Given these patterns, it is possible that the value of breastfeeding is established in childhood and adolescence, which for immigrant women would have occurred in the country of origin. Although we were not able to test the impact of these factors or the role of traditional postpartum rituals in our analyses, future studies should examine how they affect variability in breastfeeding rates among immigrant women.

Our findings have implications for clinical practice in maternal and child health settings and other community‐based health care contexts. Despite the known benefits of breastfeeding, high initiation rates in most countries are followed by a rapid decline in exclusivity, especially among those that are high income. For example, in the United States, following a breastfeeding initiation rate of 81%, only 44% of women exclusively breastfeed to 12‐week postpartum (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2016). Similar trajectories are seen in Canada and other high‐income countries, with rates of exclusive breastfeeding ranging from 3% to 44% by 24 weeks (Statistics Canada, 2017). In many cases, discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding occurs early in the postpartum period due to breastfeeding difficulties such as sore nipples, perceptions of insufficient milk supply (Cooke, Sheehan, & Schmied, 2003; Hall, Mercer, Teasley, et al., 2002; Mangrio, Persson, & Bramhagen, 2017; Rozga, Kerver, & Olson, 2015), and maternal mental health problems (Dennis & McQueen, 2009; Tavoulari et al., 2015), all of which are modifiable. Interventions that target breastfeeding self‐efficacy may be beneficial in addressing these issues. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy describes a woman's self‐confidence in her breastfeeding ability based on: (1) her previous breastfeeding experiences, (2) the encouragement she receives, (3) whether she has seen breastfeeding successfully performed or not, and (4) her physiological and psychological state (e.g, depression, anxious, fatigues, in pain) (Dennis, 1999). Higher breastfeeding self‐efficacy is associated with higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity and longer duration (Dennis, 1999). The shortened 14‐item Breastfeeding Self‐Efficacy Scale was developed to evaluate this construct and has been translated to multiple languages, making them useful for application in immigrant women (Dennis, 2003). Breastfeeding interventions should also consider maternal mental health given postpartum depression is a risk factor for breastfeeding discontinuation (Dennis & McQueen, 2007). Our findings suggest that universal interventions, regardless of immigrant status, are necessary to improve breastfeeding exclusivity rates and continued duration up to 2 years or longer. However, in providing advice to new mothers, health care providers should recognize the importance of social and cultural factors in potentially influencing breastfeeding practices among immigrant women (Schmied et al., 2012) and future research is warranted.

4.1. Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, 15 of the 29 studies were impacted by high risk of confounding. Inadequate control for confounding factors may have influenced our findings. Second, there was substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of their contexts, including different countries of origin, different cultural backgrounds, different host countries and different lengths of stay in the host country among immigrant women. Although we used random effects models to account for this heterogeneity, it impacts our ability to make definitive conclusions about the observed associations. Publication bias may have affected our findings in that small studies reporting a larger difference in breastfeeding rates between immigrant and non‐immigrant women were more likely to be published than small studies that reported a smaller or no difference. However, although pooled estimates attenuated slightly after accounting for small study effects, results were robust in these sensitivity analyses overall. Finally, according to the World Bank classification of “high‐income economies,” all of the host countries included in our review were high‐income countries. Our results may therefore not be generalizable to women who immigrate to low‐ or middle‐income countries. Because breastfeeding cultures and practices may differ across countries with different economies and years of residency in the host country, and we were not able to control for such factors; future studies should examine how this impacts breastfeeding patterns among immigrant women.

5. CONCLUSION

In our meta‐analysis, immigrant status was not significantly associated with a meaningful difference in exclusive breastfeeding initiation or duration. However, immigrant status conferred a small increase in initiation of any (exclusive or partial) breastfeeding and was also significantly associated with duration of any breastfeeding in the first 24‐week postpartum. These findings underscore the importance of providing universal interventions that target factors known to be associated with breastfeeding exclusivity, including breastfeeding self‐efficacy and mental health, to all women regardless of their immigrant status. Nevertheless, given that immigrants represent between one in 10 to one in four women in most high‐income countries (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016; Brown & Patten, 2014), such interventions should be sensitive to the influence of the cultures to which women are exposed and individual adaptation to the host country. Modifications of universal interventions may be needed to tailor care to the needs of immigrant women.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

CLD conceptualized, designed, secured funding and supervised data collection and initial analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. VS conceptualized the study and participated in the initial search of literature. KFH conceptualized the meta‐analyses, collected data, carried out the analyses, drafted Sections 2 and 3 and revised the manuscript. HKB and HPS drafted the Sections 1 and 4 and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supporting information

Data S1

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Research Chairs program for funding to complete this study.

Dennis C‐L, Shiri R, Brown HK, Santos HP Jr, Schmied V, Falah‐Hassani K. Breastfeeding rates in immigrant and non‐immigrant women: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12809 10.1111/mcn.12809

REFERENCES

- Ahluwalia, I. B. , D'Angelo, D. , Morrow, B. , & McDonald, J. A. (2012). Association between acculturation and breastfeeding among Hispanic women: Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System. Journal of Human Lactation, 28(2), 167–173. 10.1177/0890334412438403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Tajir, G. K. , Sulieman, H. , & Badrinath, P. (2006). Intragroup differences in risk factors for breastfeeding outcomes in a multicultural community. Journal of Human Lactation, 22(1), 39–47. 10.1177/0890334405283626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . (2016). Optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Committee Opinion No. 658. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(2), e86–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo‐Olivo, S. , Stiles, C. R. , Hagen, N. A. , Biondo, P. D. , & Cummings, G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . (2016). Census of population and housing: Australia revealed. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017 [Internet] Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/2024.0Main%20Features22016. Accessed March 12, 2018.

- Bandyopadhyay, M. , Small, R. , Watson, L. F. , & Brown, S. (2010). Life with a new baby: How do immigrant and Australian‐born women's experiences compare? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34(4), 412–421. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharat Pour, M. , Bergstrom, A. , Bottai, M. , Magnusson, J. , Kull, I. , & Moradi, T. (2016). Age at adiposity rebound and body mass index trajectory from early childhood to adolescence: Differences by breastfeeding and maternal immigration background. Pediatric Obesity, 12(1), 75–84. 10.1111/ijpo.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck, K. A. , Freeman, K. , & Trombley, M. (2005). Country of origin and race/ethnicity: Impact on breastfeeding intentions. Journal of Human Lactation, 21(3), 320–326. 10.1177/0890334405278249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. , & Patten, E. (2014). Statistical portrait of the foreign‐born population in the United States, 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Bulk‐Bunschoten, A. M. , Pasker‐de Jong, P. C. , van Wouwe, J. P. , & de Groot, C. J. (2008). Ethnic variation in infant‐feeding practices in the Netherlands and weight gain at 4 months. Journal of Human Lactation, 24(1), 42–49. 10.1177/0890334407311338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busck‐Rasmussen, M. , Villadsen, S. F. , Norsker, F. N. , Mortensen, L. , & Andersen, A. M. (2014). Breastfeeding practices in relation to country of origin among women living in Denmark: A population‐based study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(10), 2479–2488. 10.1007/s10995-014-1486-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention . (2016). Breastfeeding report card, progressing toward national breastfeeding goals: United States, Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention; 2016.

- Chen, S. , Binns, C. W. , Zhao, Y. , Maycock, B. , & Liu, Y. (2013). Breastfeeding by Chinese mothers in Australia and China: the healthy migrant effect. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association., 29(2), 246–252. 10.1177/0890334413475838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, M. , Sheehan, A. , & Schmied, V. (2003). A description of the relationship between breastfeeding experiences, breastfeeding satisfaction, and weaning in the first 3 months after birth. Journal of Human Lactation, 19, 145–156. 10.1177/0890334403252472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Amici, D. , Gasparoni, A. , Guala, A. , & Klersy, C. (2001). Does ethnicity predict lactation? A study of four ethnic communities. European Journal of Epidemiology, 17(4), 357–362. 10.1023/A:1012731713393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. (2003). The breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale: psychometric assessment of the short form. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 32(6), 734–744. 10.1177/0884217503258459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. (1999). Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: A self‐efficacy framework. Journal of Human Lactation, 15(3), 195–201. 10.1177/089033449901500303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. , Fung, K. , Grigoriadis, S. , Robinson, G. E. , Romans, S. , & Ross, L. (2007). Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: A qualitative systematic review. Women's Health, 3(4), 487–502. 10.2217/17455057.3.4.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. , Gagnon, A. , Van Hulst, A. , & Dougherty, G. (2014). Predictors of breastfeeding exclusivity among migrant and Canadian‐born women: Results from a multi‐centre study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10(4), 527–544. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00442.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. , Gagnon, A. , Van Hulst, A. , Dougherty, G. , & Wahoush, O. (2013). Prediction of duration of breastfeeding among migrant and Canadian‐born women: Results from a multi‐center study. The Journal of Pediatrics, 162(1), 72–79. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. , & McQueen, K. (2007). Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Paediatrica, 96(4), 590–594. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C. L. , & McQueen, K. (2009). The relationship between infant feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: A qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics, 123, e736–e751. 10.1542/peds.2008-1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew, J. H. , Barrie, J. , Horacek, I. , & Kitchen, W. H. (1978). Factors influencing jaundice in immigrant Greek infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 53(1), 49–52. 10.1136/adc.53.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval, S. , & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel‐plot‐based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman, A. I. , & Schanler, R. J. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farchi, S. , Asole, S. , Chapin, E. M. , & Di Lallo, D. (2016). Breastfeeding initiation rates among immigrant women in central Italy between 2006 and 2011. The Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 29(2), 344–348. 10.3109/14767058.2014.1001358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman‐Winter, L. B. , Schanler, R. J. , O'Connor, K. G. , & Lawrence, R. A. (2008). Pediatricians and the promotion and support of breastfeeding. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(12), 1142–1149. 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, D. A. , McLachlan, H. L. , & Lumley, J. (2006). Factors associated with breastfeeding at six months postpartum in a group of Australian women. International Breastfeeding Journal, 1, 18 10.1186/1746-4358-1-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson‐Davis, C. M. , & Brooks‐Gunn, J. (2006). Couples' immigration status and ethnicity as determinants of breastfeeding. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 641–646. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groleau, D. , Souliere, M. , & Kirmayer, L. J. (2006). Breastfeeding and the cultural configuration of social space among Vietnamese immigrant women. Health & Place, 12, 516–526. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. T. , Mercer, A. , Teasley, S. L. , et al. (2002). A breastfeeding assessment score to evaluate the risk for cessation of breast‐feeding by 7‐10 days of age. The Journal of Pediatrics, 141, 659–664. 10.1067/mpd.2002.129081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley, K. , Stamm, N. L. , & Eskenazi, B. (2007). The effect of time in the U.S. on the duration of breastfeeding in women of Mexican descent. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11(2), 119–125. 10.1007/s10995-006-0152-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, S. S. , Gillman, M. W. , Shafer, E. F. , & Cohen, B. B. (2014). Acculturation and maternal health behaviors: findings from the Massachusetts birth certificate. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(2), 150–159. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, S. S. , Lamb, K. , Cole, T. J. , & Law, C. (2008). Influence of moving to the UK on maternal health behaviours: Prospective cohort study. BMJ, 336(7652), 1052–1055. 10.1136/bmj.39532.688877.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, C. E. , & Potter, J. E. (2017). Nativity, country of education, and Mexican‐origin women's breastfeeding behaviors in the first 10 month postpartum. Birth, 44(1), 68–77. 10.1111/birt.12261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (Accessed May 1, 2016)

- Higgins, J. P. , & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer, C. S. , Sheehan, A. , & Cooke, M. (2002). Initial infant feeding decisions and duration of breastfeeding in women from English, Arabic and Chinese‐speaking backgrounds in Australia. Breastfeeding Review, 10(2), 27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbro, R. T. , Lynch, S. M. , & McLanahan, S. (2008). The influence of acculturation on breastfeeding initiation and duration for Mexican‐Americans. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(2), 183–199. 10.1007/s11113-007-9059-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocturk, T. (1988). Advantages of breastfeeding according to Turkish mother's living in Istanbul and Stockholm. Social Science & Medicine, 27(4), 405–410. 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornosky, J. L. , Peck, J. D. , Sweeney, A. M. , Adelson, P. L. , & Schantz, S. L. (2008). Reproductive characteristics of Southeast Asian immigrants before and after migration. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(2), 135–143. 10.1007/s10903-007-9064-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, S. C. , Hsu, C. H. , Li, C. Y. , Lin, K. C. , Chen, C. H. , Gau, M. L. , & Chou, Y. H. (2008). Community‐based epidemiological study on breastfeeding and associated factors with respect to postpartum periods in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(7), 967–975. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, M. K. , Leung, G. M. , & Schooling, C. M. (2013). Breast feeding and early adolescent behaviour, self‐esteem and depression: Hong Kong's 'Children of 1997′ birth cohort. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98(11), 887–894. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbok, M. , & Krasovec, K. (1990). Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Studies in Family Planning, 21(4), 226–230. 10.2307/1966617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladewig, E. L. , Hayes, C. , Browne, J. , Layte, R. , & Reulbach, U. (2014). The influence of ethnicity on breastfeeding rates in Ireland: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(4), 356–362. 10.1136/jech-2013-202735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. J. , Elo, I. T. , McCollum, K. F. , & Culhane, J. F. (2009). Racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration among low‐income, Inner‐City Mothers. Social Science Quarterly, 90(5), 1251–1271. 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00656.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. J. , Rubio, M. R. , Elo, I. T. , McCollum, K. F. , Chung, E. K. , & Culhane, J. F. (2005). Factors associated with intention to breastfeed among low‐income, inner‐city pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 9(3), 253–261. 10.1007/s10995-005-0008-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, B. M. , McDonald, S. W. , Kaplan, B. J. , Giesbrecht, G. F. , & Tough, S. C. (2013). Comparison of sample characteristics in two pregnancy cohorts: Community‐based versus population‐based recruitment methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 149 10.1186/1471-2288-13-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey, M. W. , & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta‐analysis. New York, NY: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mangrio, E. , Persson, K. , & Bramhagen, A. C. (2017). Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32, 451–465. 10.1111/scs.12489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, H. L. , & Forster, D. A. (2006). Initial breastfeeding attitudes and practices of women born in Turkey, Vietnam and Australia after Giving Birth in Australia. International Breastfeeding Journal, 1, 7 10.1186/1746-4358-1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt, L.‐A. , Wu, C. , Xue, X. , & Hafner, J. P. (2003). Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(10), 940–943. 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten, S. , Wyss, C. , & Ackermann‐Liebrich, U. (2007). Caesarean sections and breastfeeding initiation among migrants in Switzerland. International Journal of Public Health, 52(4), 210–222. 10.1007/s00038-007-6035-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. , & Group P . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neault, N. B. , Frank, D. A. , Merewood, A. , Philipp, B. , Levenson, S. , Cook, J. T. , … Children's Sentinel Nutrition Assessment Program Study Group . (2007). Breastfeeding and health outcomes among citizen infants of immigrant mothers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(12), 2077–2086. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor, S. Z. , & Rousham, E. K. (2008). Breast‐feeding and maternal mental well‐being among Bangladeshi and Pakistani women in north‐east England. Public Health Nutrition, 11(5), 486–492. 10.1017/S1368980007000912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, L. L. , Henderson, J. , Redshaw, M. , & Quigley, M. A. (2014). The role of support and other factors in early breastfeeding cessation: An analysis of data from a maternity survey in England. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 88 10.1186/1471-2393-14-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, B. L. , Merewood, A. , Miller, L. W. , Chawla, N. , Murphy‐Smith, M. M. , Gomes, J. S. , … Cook, J. T. (2001). Baby‐friendly hospital initiative improves breastfeeding initiation rates in a US hospital setting. Pediatrics, 108(3), 677–681. 10.1542/peds.108.3.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posmontier, B. , & Horowitz, J. A. (2004). Postpartum practices and depression prevalences: Technocentric and ethnokinship cultural perspectives. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 15, 34–43. 10.1177/1043659603260032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio, I. , Castello‐Pastor, A. , Del Val, S.‐V. M. , et al. (2011). Breastfeeding initiation in immigrant and non‐immigrant women in Spain. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(12), 1345–1347. 10.1038/ejcn.2011.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, J. C. , & Yam, B. M. (2000). Breastfeeding: how could it be enhanced? The perceptions of Vietnamese women in Sydney, Australia. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 45(3), 271–276. 10.1016/S1526-9523(00)00013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, H. , Sutton, A. , & Borenstein, M. (2005). Publication bias in meta‐analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/0470870168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roville‐Sausse, F. N. (2005). Westernization of the nutritional pattern of Chinese children living in France. Public Health, 119(8), 726–733. 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozga, M. R. , Kerver, J. M. , & Olson, B. H. (2015). Self‐reported reasons for breastfeeding cessation among low‐income women enrolled in a peer counseling breastfeeding support program. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(1), 129–137. 10.1177/0890334414548070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied, V. , Olley, H. , Burns, E. , Duff, M. , Dennis, C. L. , & Dahlen, H. G. (2012). Contradictions and conflict: a meta‐ethnographic study of migrant women's experiences of breastfeeding in a new country. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12, 163 10.1186/1471-2393-12-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G. K. , Kogan, M. D. , & Dee, D. L. (2007). Nativity/immigrant status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the United States, 2003. Pediatrics, 119(Suppl 1), S38–S46. 10.1542/peds.2006-2089G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . (2015). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity in Canada. Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . (2017). Immigrant women. Statistics Canada, [Internet]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14217-eng.htm#a1 Accessed March 12, 2018.

- Sussner, K. M. , Lindsay, A. C. , & Peterson, K. E. (2008). The influence of acculturation on breast‐feeding initiation and duration in low‐income women in the US. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(5), 673–696. 10.1017/S0021932007002593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavoulari, E. F. , Benetou, V. , Vlastarakos, P. V. , Kreatsas, G. , & Linos, A. (2015). Immigrant status as important determinant of breastfeeding practice in southern Europe. Central European Journal of Public Health, 23(1), 39–44. 10.21101/cejph.a4092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, World Health Organization, 1000 Days, and Alive & Thrive . (2017) Nurturing the health and wealth of nations: the investment case for breastfeeding ‐ Global breastfeeding collective ‐ Executive summary. Geneva, WHO.

- Utaka, H. , Li, L. , Kagawa, M. , Okada, M. , Hiramatsu, N. , & Binns, C. (2005). Breastfeeding experiences of Japanese women living in Perth, Australia. Breastfeeding Review, 13(2), 5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinden, K. , Levecque, K. , & Van Rossem, R. (2015). Breastfeeding or bottled milk? Poverty and feeding choices in the native and immigrant population in Belgium. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(2), 319–324. 10.1007/s10903-014-0072-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verga, M. E. , Widmeier‐Pasche, V. , Beck‐Popovic, M. , Pauchard, J. Y. , & Gehri, M. (2014). Iron deficiency in infancy: is an immigrant more at risk? Swiss Medical Weekly, 144, w14065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, J. (2001). The economic benefits of breastfeeding: A review and analysis. Report no. 13. Whashington: U.S: Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2011). Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W. C. , Wu, J. C. , & Chiang, T. L. (2015). Variation in the association between socioeconomic status and breastfeeding practices by immigration status in Taiwan: A population based birth cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, 298 10.1186/s12884-015-0732-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuppa, A. A. , Orchi, C. , Calabrese, V. , Verrillo, G. , Perrone, S. , Pasqualini, P. , … Romagnoli, C. (2010). Maternal and neonatal characteristics of an immigrant population in an Italian hospital. The Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 23(7), 627–632. 10.3109/14767050903258761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Supporting Information