Abstract

Recent research has highlighted associations of breastfeeding with IQ, schooling, and income, but uncertainty about such links remains. The Indonesian Family Life Survey, representative of 83% of the Indonesian population, provides data on breastfeeding, parents' years of schooling, wealth, and other family characteristics in 1993–1994, as well as schooling and income in 2014–2015 for 5,421 children of those families. Using linear regressions and controlling for village or neighbourhood, as well as propensity score matching, we analysed breastfeeding associations for boys and girls separately, when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk is significantly associated with years of schooling in 2014–2015 for girls, but not for boys, after controlling for the village or neighbourhood of residence in 1993–1994. For girls, ages 1 to 1.9, 2 to 2.9, 3 to 3.9, and >4 months, relative to ages <1 month, are associated with an additional 0.41 to 0.46 years of schooling, with p values of 0.086, 0.071, 0.043, and 0.026, respectively. No comparable estimate for boys attains statistical significance. Using propensity score matching yields similar results. Associations with annual income in 2014–2015 are not statistically significant, either for all children, or for either sex. Our finding suggests that delaying regular feeding of foods/beverages other than breast milk beyond 1 month may help girls' schooling but has no observable association with annual income, perhaps because of lower labour force participation by women. Also, the inclusion of controls for village or neighbourhood of residence reduces confounding.

Key messages.

Using data from the Indonesian Family Life Survey, and controlling for village or neighbourhood, as well as propensity score matching, we analysed breastfeeding associations for boys and girls separately.

Ages when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk is significantly associated with years of schooling in 2014–2015 for girls, but not for boys, after controlling for the village or neighbourhood of residence in 1993–1994.

For girls, ages 1 to 1.9, 2 to 2.9, 3 to 3.9, and >4 months, relative to ages <1 month, are associated with an additional 0.41 to 0.46 years of schooling, with p values of 0.086, 0.071, 0.043, and 0.026, respectively. No comparable estimate for boys attains statistical significance.

Our finding suggests that delaying regular feeding of foods/beverages other than breast milk beyond 1 month may help girls' schooling but has no observable association with annual income, perhaps because of lower labour force participation by women.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding may boost IQ, according to meta‐analyses (Horta, Loret de Mola, & Victora, 2015; Victora et al., 2016), longitudinal studies (Borra, Iacovou, & Sevilla, 2012; Rothstein, 2013), and a randomized trial (Kramer et al., 2008). Studies from the United Kingdom (Martin, Goodall, Gunnell, & Smith, 2007; Richards, Hardy, & Wadsworth, 2002), the United States (Rees & Sabia, 2009), and New Zealand (Horwood & Fergusson, 1998), as well as new research from India (Nandi, Lutter, & Laxminarayan, 2017), have reported positive associations between breastfeeding and schooling outcomes. A 30‐year follow‐up of a birth cohort in Pelotas, Brazil, found that breastfeeding predicts increases of 3.8 IQ points in adults, of 0.9 years of schooling, and of 34% of median income (Victora et al., 2015). These findings point to refining infant nutrition policy to encompass breastfeeding as a means to promote future adult outcomes (Victora et al., 2016). Global breastfeeding experts have recently argued that breastfeeding should be seen as an investment in human capital (World Bank, 2016).

Key questions remain, however, about the relationship between breastfeeding and nonhealth outcomes such as schooling and income that are important for lifelong welfare. A study of five cohorts in low‐ and middle‐income countries found “the early intellectual advantage of breastfed infants that is clearly documented in the literature is not paralleled by higher achieved schooling,” and measures of breastfeeding are “not consistently related to schooling achievement in contemporary cohorts of young adults” (Horta et al., 2013). Moreover, there are large differences among low‐income countries in breastfeeding practices (Lutter & Lutter, 2012), as well as educational and employment opportunities, so results from one country may not apply elsewhere. Finally, except for one randomized trial (Kramer et al., 2008), the available evidence relies on observational data and so indicates causal relationships only if residual confounding from omitted variables is negligible. Thus, there may be value in considering new analytic approaches.

Neighbourhoods where young children are raised affect subsequent schooling and adult labour market outcomes—at least experimental evidence from a U.S. housing voucher programme shows that moving from high‐poverty to low‐poverty neighbourhoods early in childhood increases earnings and college attendance while reducing single parenthood rates (Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2016). In addition, differences in childhood environments in the United States matter for gender gaps in adult income, which vary substantially across counties and commuting zones where children grew up (Chetty, Hendren, Lin, Majerovitz, & Scuderi, 2016).

Similar neighbourhood effects are likely to occur in developing nations, but our literature review did not find previous studies linking educational outcomes to breastfeeding in low‐income countries that used statistical controls for neighbourhoods or villages. The data we analysed, the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), identify 321 enumeration areas that correspond to villages or urban neighbourhoods, permitting the inclusion of controls for local place effects.

Families' decisions regarding schooling for sons are typically different than for daughters (Koch, Nafziger, & Nielsen, 2015; Uysal, 2010). Our review of prior research linking educational outcomes to breastfeeding in developing countries identified limited research focusing on differences by sex in developing countries without preferences for sons. A five‐cohort study reported stratification by sex and found that “for Guatemala (but not in the other sites) the association between duration of breastfeeding and achieved schooling was modified by sex” and among males positive while for females “in the opposite direction” (Horta et al., 2013). A report from New Zealand reported finding no evidence to suggest that the association of breastfeeding with schooling outcomes varied with the child's sex (Horwood & Fergusson, 1998).

We aimed to assess the sex‐specific associations between breastfeeding and schooling and earned income while also controlling for detailed household characteristics and the neighbourhoods or villages where children grew up.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

The IFLS, an ongoing longitudinal survey representative of some 83% of the Indonesian population, provides information about breastfeeding and subsequent schooling and labour market outcomes (Frankenberg et al., 1995; Strauss, Witoelar, & Sikoki, 2016). In 1993–1994, researchers from the Lembaga Demografi, University of Indonesia, and the Rand Corporation conducted the first wave of the IFLS. Other researchers have described IFLS data in detail (Majid, 2015; Van Ewijk, 2011). We matched data on breastfeeding and family characteristics from the first wave of IFLS (1993–1994) with data on adult educational and labour market outcomes from Wave 5 (2014–2015). In our final sample, respondents with complete schooling information are between the age of 1 and 22 years in the first wave and between the ages of 21 and 42 in the fifth wave. Specifically, the analysis sample includes 3,027 (56%) respondents with ages ≤10 years, 1,455 (27%) with ages >10 and ≤15 years, and 939 (17%) with ages >15 and ≤22 years at the time of the first wave in 1993–1994. IFLS provides a rich set of variables likely to affect families' schooling decisions and later labour market outcomes including maternal and head‐of‐household's schooling, indicators for possession of each of eight different types of physical or financial assets, religion, whether the mother or head of household has a tobacco smoking habit, the age of the mother at birth, and the number of older siblings, as well as the year and month of birth. IFLS identifies 321 enumeration areas—which represent a village or urban neighbourhood.

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Virginia approved this research.

2.2. Procedures

We downloaded and merged data from IFLS Waves 1 and 5. Wave one files contained data on maternal and head of household schooling, family demographics and assets, birth months and years, and breastfeeding as well as the enumeration area where the initial survey was conducted. Files from Wave 5 provided data on years of completed schooling, employment status, and income.

Our analysis of breastfeeding focused on the question “How old was the child when he/she was regularly fed other food/beverages besides breast milk?” This question is related to the age of introduction of complementary foods as defined by the World Health Organization (2010). All breastfeeding information used here was collected in 1993–1994. Responses were mostly recorded in months (78.3%), with some in days (17.1%) and the remainder (4.6%) in weeks. We converted weekly and daily responses to months, using 30 days as the equivalent of 1 month and rounding answers to the nearest 0.25 month. Following Victora et al. (2015), we used breastfeeding age categories of <1, 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, and ≥4 months. We also investigated associations with duration of any breastfeeding (whether or not regular foods had been introduced). In Indonesia, the duration of any breastfeeding was quite long: In our sample, more than 93% of both boys and girls were breastfed for over 6 months, around 85% beyond 12 months, and around 56% for at least 24 months.

Schooling and income data from IFLS are of high quality (Dong, 2016) and have been used in multiple high‐profile studies (Bedi & Garg, 2000; LaFave & Thomas, 2017; Maccini & Yang, 2009). We constructed a variable for years of schooling completed based on 6 years of elementary school, 3 years of junior high school, 3 years of senior high school, and 4 years of college or above. We use income based on both wages and net income from self‐employment. For a country in which 60% of employment is self‐employed, having income information on the self‐employed is crucial for getting the complete picture of the labour market. The annual income measure relied on responses to the questions “Approximately what was your salary/wage during the last year?” and “Approximately how much net profit did you gain last year?” We included valid responses indicating zero income.

We analysed alternative specifications for income, including dropping observations with zero income, using a log transformation of income for those with nonzero values, and top‐coding values for annual income at the 99th percentile value.

Our sample includes children who were teenagers at the time of Wave 1 survey, in 1993–1994. We addressed the possibility of misclassification in age when they were regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk by visual inspection for clustering of responses, and use of alternative categorizations centred on integer numbers of months.

2.3. Statistical analysis

IFLS provides breastfeeding and schooling information for 5,421 children born before the first‐wave interviews. We estimated OLS multiple linear regression models to derive the estimated associations after controlling for both household level characteristics (child gender, birth year and month, number of older siblings, mother's age at birth, education and religion, household head's education and religion, mother's and household head's tobacco use, and types of household assets) and fixed effects for enumeration areas. In all linear models, we clustered standard errors at the enumeration area level. We also employed propensity score matching (PSM) to compare the associations between children who were breastfed for less than 1 month and those who were breastfed for 1 month or more. Probit model was used to compute the propensity score, and the nearest neighbour method was employed to compute the average treatment effect. We also used a variety of different PSM estimators as robustness checks. We computed the standard errors following Abadie and Imbens (2006, 2011, 2016).

We based statistical comparisons between categories on t tests relative to the omitted category. We used Stata 14.2 for the analyses. Appendix S1 provides our STATA computer programs and instructions on data access.

2.4. Role of the funding source

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under Grant GF13203 and Project No.148152. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents summary statistics for key variables. (Appendix SA provides additional details.) Twenty‐one percent of children are less than 1 month of age when first regularly fed food/beverages other than breast milk. Differences between boys and girls when regularly fed food/beverages other than breast milk are small. Girls in our sample have a quarter year more schooling than boys. Mean annual earnings among females in 2014–2015 are 43% as large as for males ($753 versus $1,764) in part because women are much less likely to be engaged in market work.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of participants

| Variable | Descriptive statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Boys | Girls | ||

| Age when regularly fed food/beverages other than breast milk (months)a | <1 | 1,137 (21·0%) | 558 (21·0%) | 579 (21·0%) |

| 1–1·9 | 582 (10·7%) | 297 (11·1%) | 285 (10·3%) | |

| 2–2·9 | 540 (9·96%) | 267 (10·0%) | 273 (9·9%) | |

| 3–3·9 | 1,023 (18·9%) | 513 (19·2%) | 510 (18·5%) | |

| ≥4 | 2,139 (39·5%) | 1,031 (38·7%) | 1,108 (40·2%) | |

| Age in years during Wave 5b | 29·7 (5·5) | 29·8 (5·6) | 29·7 (5·5) | |

| Years of schooling completedb | 11·05 (3·38) | 10·93 (3·37) | 11·16 (3·38) | |

| Annual earnings (2016 US$) meanb | 1,257·7 (2,654·0) | 1,763·8 (2,891·7) | 753·2 (2,282·1) | |

| Number of observations | 5,421 | 2,666 | 2,755 | |

Numbers of observations and percentages.

Mean (SD).

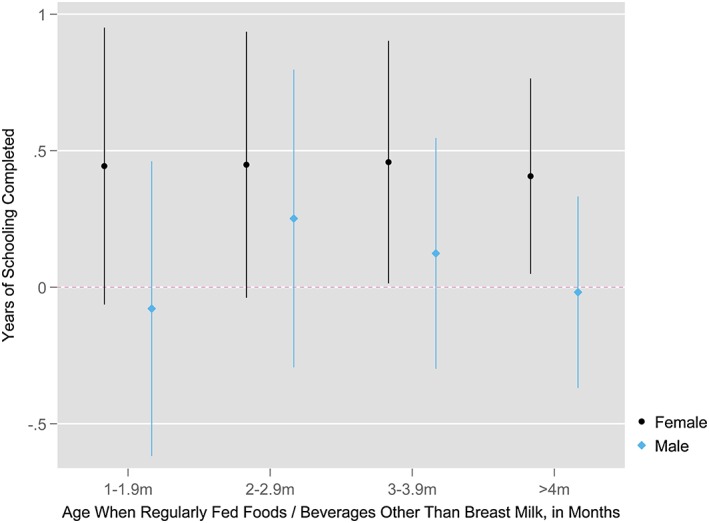

Table 2 presents estimates of the association between the age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk and years of schooling. Model 1 includes controls for mother's and household head's years of schooling, religion, tobacco habits, and indicator variables for owning houses, land, cattle, vehicle, appliance, savings, stocks, receivables, jewellery, and other assets, as well as for the mother's age, the child's birth year and birth month, and the number of older siblings. We categorized respondents according to the age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, and use the category of less than 1 month in age as a no exposure group. Using these controls and categorizations, breastfeeding duration is significantly and positively associated with future schooling. Specifically, breastfeeding from 2 to 2.9, 3 to 3.9, and more than 4 months is associated with significantly increased schooling of 0.42, 0.41, and 0.24 years, respectively, compared with the no exposure group. The estimates decline, with the inclusion of fixed effects for villages and urban neighbourhoods, as shown in model (2), where the associations for 2 to 2.9, 3 to 3.9, and more than 4 months are 0.36, 0.32, and 0.23 years, respectively, and only the association for ages 3 to 3.9 months is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level, although the differences are always significant at the 90% level compared with the no exposure group. The fixed effects for enumeration areas are jointly significant (p < 0.001). All associations between the age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk and years of schooling are greater for girls than boys, and not statistically significant for boys (Figure 1). For girls, the estimates vary little with increases in the age of girls when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, ranging from 0.44 to 0.46 years for ages 1 to 1.9, 2 to 2.9, 3 to 3.9, and falling to 0.41 months for ages ≥4.0 months when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, all relative to ages <1 month. The associations for girls presented in model 2 are significant at the 90% level for ages 1–1.9 and 2–2.9 months, and at the 95% level for ages 3–3.9 and ≥4.0 months.

Table 2.

Multiple regression model results

| Mean dependent variable (95% CI) | Regression estimates (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 2 | Model 2 | |||

| Boys and girls | Boys | Girls | ||||

| Dependent variable: years of schooling | ||||||

| Age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk (months) | <1 | 10·38 (10·17 to 10·58) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) |

| 1–1·9 | 10·66 (10·40 to 10·93) | 0·112 (−0.254 to 0·478) | 0·196 (−0·181 to 0·573) | −0·078 (−0·618 to 0·462) | 0·444 (−0·064 to 0·951) | |

| 2–2·9 | 11·53 (11·25 to 11·81) | 0·422 (0·053 to 0·792) | 0·362 (−0·011 to 0·734) | 0·252 (−0·294 to 0·797) | 0·449 (−0·039 to 0·936) | |

| 3–3·9 | 11·83 (11·63 to 12·02) | 0·408 (0·101 to 0·714) | 0·318 (0·001 to 0·636) | 0·124 (−0·299 to 0·547) | 0·458 (0·014 to 0·902) | |

| ≥4 | 11·01 (10·87 to 11·16) | 0·242 (−0·019 to 0·503) | 0·229 (−0.255 to 0·484) | −0·018 (−0·369 to 0·333) | 0·407 (0·049 to 0·765) | |

| N | 5421 | 2666 | 2755 | |||

| R2 | NA | 0·353 | 0·460 | 0·482 | 0·529 | |

| Dependent variable: annual income | ||||||

| Age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, months | <1 | 1,064·6 (945·2 to 1,184·0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) |

| 1–1·9 | 1,306·0 (1,070·0 to 1,541·9) | 119·0 (−139·7 to 377·7) | 78·3 (−200·1 to 356·6) | −10·0 (−408·4 to 388·4) | 168·4 (−279·1 to 615·9) | |

| 2–2·9 | 1,527·3 (1,263·2 to 1,791·4) | 223·1 (−60·7 to 506·8) | 131·4 (−136·1 to 398·9) | 127·2 (−381·9 to 636·2) | 124·5 (−266·2 to 515·1) | |

| 3–3·9 | 1,317·7 (1,167·7 to 1,467·7) | −119·6 (−325·1 to 85·9) | −116·3 (−345·1 to 112·6) | −261·3 (−664·1 to 141·4) | 79·9 (−159·2 to 318·9) | |

| ≥4 | 1,231·9 (1,113·0 to 1,350·8) | 32·7 (−137·7 to 203·0) | 1·9 (−174·6 to 178·3) | −131·6 (−424·2 to 161·0) | 92·3 (−93·5 to 278·2) | |

| N | 5,466 | 2,692 | 2,774 | |||

| R2 | NA | 0·109 | 0·191 | 0·253 | 0·228 | |

Note. Model 1 controls for mother's age, mother's and household head's years of schooling; religion; tobacco habits; household assets including indicators for owning houses, land, cattle, vehicle, appliance, savings, stocks, receivables, jewellery, and other assets; the child's birth year and birth month; and the number of older siblings. Model 2, our preferred specification, also includes fixed effects for geographic enumeration areas, which typically reflect an urban neighbourhood or a village or even smaller area. Standard errors are clustered at the EA level.

Figure 1.

Age when regularly fed food/beverages other than breast milk and years of schooling

Table 2 also presents estimates from additional regression models that substitute annual income for years of schooling as the dependent variable. The estimates for boys and girls combined are not statistically significant in Models 1 and 2 (with and without fixed effects for enumeration areas), nor for boys and girls separately, with enumeration area fixed effects, although the coefficients are uniformly positive for girls. We also estimated additional regressions using an indicator of labour force participation status as the dependent variable. Again, we found no statistically significant association of breastfeeding duration with labour force participation for either the combined sample, or for boys and girls separately (see Appendix SE).

We found little evidence of concern about bias resulting from sample attrition occurring between Waves 1 and 5 of the survey. For both boys and girls, the final sample is very similar to the initial (Wave 1) sample in terms of age, number of older siblings, age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, mothers' and household heads' schooling, and household assets—none of these variable means were statistically significantly different between the initial and final sample, for either boys or girls (see Appendix SA).

Some of our breastfeeding data relied on relatively lengthy recall. To address the possibility of measurement error in the age when infants are regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk, we divided our final sample into four subsamples based on age in the first IFLS wave: ≤5 years old, >5 and ≤10 years old, >10 and ≤15 years old, and >15 years old, and plotted the distribution of breastfeeding durations using the four subsamples, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. The plots by subsamples almost coincide, mitigating concerns regarding recall bias. As an additional sensitivity analysis, we also re‐estimated the prior models using alternative categorizations centred on in the middle of the exact month (≤0.5, 0.6 to 1.5, and 1.6 to 2.5 months, etc.), to avoid potential biases that might result from rounding durations to full months. These models led to very slightly larger breastfeeding estimates, but without any difference in the conclusions (see Appendix SB).

Figure 2.

Age when regularly fed food/beverages other than breast milk, by subsamples

Alternative specifications of our model gave similar results. Following Victora et al. (2016), we re‐estimated the models after dropping all observations with zero income. We also estimated specifications where nonzero income values were transformed using natural logarithms, and other where annual income was top‐coded at the 99th percentile. These alternative specifications provide similar qualitative conclusions (see Appendix SC).

We employed PSM to estimate associations between age when regularly fed food/beverages other than breastmilk, and both schooling and income. We treated children with ages less than 1 month as the control group, and those with ages equal to or more than 1 month as the treatment group. We defined treatment in this way for two reasons: first, while standard PSM methods use a single treatment dummy and it is difficult to implement the PSM method with multiple treatment categories. Second, the EA fixed‐effects models suggest that the first month is an empirically critical cut‐off for later education outcomes.

Results of the PSM estimates are provided in Table 3. These results corroborate the findings obtained for both education and income in the linear models. Specifically, compared with children whose age when regularly fed food/beverages other than breastmilk is less than 1 month, children with longer breastfeeding duration have 0.241 more years of schooling (p = 0.041 < 0.05). When we split the samples by gender, the positive association for girls increased to 0.515 years (p < 0.001), whereas no comparable association for boys was found. We did not find significant associations between this breastfeeding measure and income in either the combined sample, or among the boys and girls separately. We have also estimated a range of alternative PSM specifications, including changing the number of neighbours when using the nearest neighbour approach, using the regression adjustment specification and using inverse probability weights. Results are robust to these alternative specifications, and the patterns and statistical significance are identical for all outcomes and subsamples.

Table 3.

Propensity score estimates

| Mean dependent variable (95% CI) | Propensity score estimates (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys and girls | Boys | Girls | |||

| Dependent variable: years of schooling | |||||

| Age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk (months) | <1 | 10·38 (10·17 to 10·58) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) |

| ≥1 | 11·23 (11·13 to 11·33) | 0·241 (0·009 to 0·472) | 0·144 (−0·171 to 0·460) | 0·515 (0·303 to 0·727) | |

| N | 5,421 | 2,666 | 2,752 | ||

| Dependent variable: annual income | |||||

| Age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk (months) | <1 | 1,064·6 (945·2 to 1,184·0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) | Reference (0) |

| ≥1 | 1,299·9 (1,216·5 to 1,383·2) | 90·6 (−92·9 to 274·2) | 73·5 (−210·2 to 357·2) | −102·3 (−311·1 to 106·6) | |

| N | 5,466 | 2,692 | 2,771 | ||

Note. The propensity score matching models include all the same controls as the linear models in Table 2, except for EA dummies, because they cause computational problems for the initial propensity score calculation. Instead, we include a set of EA‐level characteristics, including whether the EA had electricity, its main water access types, sewage types, and whether it had access to credit. When estimating the model for the girls subsample, three observations have very low propensity scores (below 10−5), and we drop these three observations. The relevant Stata command is teffects psmatch (probit), vce (r). Confidence intervals calculated using robust Abadie‐Imbens standard errors.

Additionally, we have also examined the associations between the duration of any breastfeeding and years of schooling/income using linear models. We found no statistically significant associations (see Appendix SF).

4. DISCUSSION

We have used the IFLS data to estimate associations between the age when infants are regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk and years of schooling and income as young adults. The sex‐specific nature of our results—that age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk predicted higher levels of schooling for girls but not boys—is novel. An authoritative review by Victora et al. (2016) scarcely mentioned that effects of breastfeeding duration might differ by sex and this issue has to our knowledge been little explored outside of India, where parents prefer sons (Jayachandran & Kuziemko, 2011). In our data, however, breastfeeding behaviour appears very similar for sons and daughters. We are unable to say why the age of regular introduction of foods and beverages other than breast milk predicts additional years of schooling in girls but not boys. One interpretation may be that families always educate boys as much as money and circumstances allow but give additional education to girls only if they are seen to be relatively more promising students, as might occur if longer breastfeeding raises (real or perceived) cognitive performance of girls and expectations of academic success. Another possibility is that mothers bond more with daughters than with sons as a result of additional breastfeeding and that such emotional bonds facilitate the nurturing that leads to greater investment in education and more schooling. Distinguishing among such competing explanations is beyond our scope and a topic for further research.

A second interesting aspect of our results is the absence of an exposure–response relationship. For girls, the age when regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk is associated with nearly a half year of additional schooling for all age categories greater than 1 month, although the youngest of these categories, 1 to 1.9 and 2 to 2.9 months, have p values that imply significance at the 90% but not the 95% level. One study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to assess maternal brain response to infant stimuli and reported that in the first postpartum month, breastfeeding mothers showed greater brain response to own infant cry than formula‐feeding mothers, in brain regions implicated in maternal–infant bonding (Kim et al., 2011). Such bonding may have effects as infants enter their social world.

We have not observed the association between breastfeeding duration and adult earned income reported from the Pelotas cohort (Victora et al., 2015). It is perhaps not surprising that there is no association with earnings among boys, since there is no observed relationship between breastfeeding duration and years of schooling for them and such an association would likely be a key mechanism through which any effects of breastfeeding on human capital and economic productivity would be manifested. Similarly, it may not be surprising that the greater schooling predicted by longer breastfeeding in girls is not reflected in higher income because labour force participation by young Indonesian women is much lower than for corresponding men (45% versus 80% in our sample). Thus, associations with income may not be observable among women because too few of them work for pay outside the home.

Breastfeeding duration may be associated with nonhealth adult outcomes beyond schooling and income. An extensive literature shows that girls' education leads to delays in pregnancy and reductions in family size, although the magnitude of such effects is uncertain (Angeles, Guilkey, & Mroz, 2005; Kim, 2010). We confirmed with our analysis sample that years of schooling for girls was associated with delays in the date of first pregnancy and reductions in total fertility, although the age that daughters were regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk did not directly predict the hazard of first pregnancy or family size in our sample (see Appendix SD).

Our econometric estimates included an unusually comprehensive set of controls for demographic characteristics of the mother, head of household and family (although we did not have information on gestational age or birthweight or other birth outcomes). However, even such rich controls are unlikely to completely control for all potentially confounding factors. An important contribution of this research was to introduce into our estimation models dummy variables for 309 enumeration areas, which control for time‐invariant unobserved variables affecting both breastfeeding practices in a given neighbourhood and other factors that might improve schooling or labour market outcomes later in life. Controlling for these “place effects” lowered our estimates of the association of age when infants were regularly fed foods/beverages other than breast milk on future educational attainment—by more than 20% for breastfeeding duration categories. These findings suggest that factors typically not controlled for may affect both later nonhealth outcomes and also breastfeeding behaviour, leading to confounding in ways that have typically not been fully accounted for (Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2016; Chetty, Hendren, Lin, et al., 2016).

Our results should be interpreted in light of several caveats. First, our main breastfeeding question—indicating the age at which the child was first regularly fed other food—does not exactly correspond with more commonly used definitions of exclusive breastfeeding. Second, although we include a wide variety of controls, remaining residual confounding is a possibility. For example, the IFLS data do not contain information on birthweight or gestational age, precluding the inclusion of controls for these factors. In preliminary work, we examined the possibility of using several instrumental variable strategies, but these were unsuccessful due to weak predictive power in the first‐stage breastfeeding equations. Third, our estimates do not indicate a consistent dose–response relationship, although we would note that this would not necessarily be needed for a causal effect (e.g., if short periods of exclusive breastfeeding trigger responses that facilitate bonding with infants). Finally, although we obtain consistent results using a variety of estimation methods, additional research is needed to explore why educational benefits of breastfeeding are observed among girls but not among boys.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All of the authors contributed to review and interpretation of existing literature, data compilation and cleaning, statistical analysis, and interpretation.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All views expressed in this paper are the sole responsibility of the authors and not necessarily those of the funder or any other organization. We appreciate Kelsey Hunt's excellent research assistance and are grateful for helpful comments from Chessa Lutter, Arindam Nandi, and Ellen Piwoz.

Lutter R, Ruhm C, Lin D, Liu S. Breastfeeding, schooling, and income: Insights from the Indonesian Family Life Survey. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12651 10.1111/mcn.12651

REFERENCES

- Abadie, A. , & Imbens, G. W. (2006). Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica, 74(1), 235–267. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie, A. , & Imbens, G. W. (2011). Bias‐corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 29(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie, A. , & Imbens, G. W. (2016). Matching on the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 84(2), 781–807. [Google Scholar]

- Angeles, G. , Guilkey, D. K. , & Mroz, T. A. (2005). The effects of education and family planning programs on fertility in Indonesia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(1), 165–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, A. S. , & Garg, A. (2000). The effectiveness of private versus public schools: The case of Indonesia. Journal of Development Economics, 61(2), 463–494. [Google Scholar]

- Borra, C. , Iacovou, M. , & Sevilla, A. (2012). The effect of breastfeeding on children's cognitive and noncognitive development. Labour Economics, 19(4), 496–515. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R. , Hendren, N. , & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R. , Hendren, N. , Lin, F. , Majerovitz, J. , & Scuderi, B. (2016). Gender gaps in childhood: Skills, behaviors, and labor market preparedness. In. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 106(5), 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, M. A. , & Uysal, G. (2010). The determinants of student achievement in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(6), 592–598. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S. X. (2016). Consistency between Sakernas and the IFLS for analyses of Indonesia's labour market: A cross‐validation exercise. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 52(3), 343–378. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg, E. , Karoly, L. A. , Gertler, P. , Achmad, S. , Agung, I. G. , Hatmadji, S. H. , & Sudharto, P. (1995). The 1993 Indonesian family life survey: Overview and field report.

- Horta, B. L. , Bas, A. , Bhargava, S. K. , Fall, C. H. , Feranil, A. , de Kadt, J. , … Victora, C. G. (2013). Infant feeding and school attainment in five cohorts from low‐and middle‐income countries. PLoS One, 8(8), e71548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B. L. , Loret de Mola, C. , & Victora, C. G. (2015). Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(S467), 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood, L. J. , & Fergusson, D. M. (1998). Breastfeeding and later cognitive and academic outcomes. Pediatrics, 101(1), e9–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, S. , & Kuziemko, I. (2011). Why do mothers breastfeed girls less than boys? Evidence and implications for child health in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3), 1485–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. (2010). Women's education and fertility: An analysis of the relationship between education and birth spacing in Indonesia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 58(4), 739–774. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P. , Feldman, R. , Mayes, L. C. , Eicher, V. , Thompson, N. , Leckman, J. F. , & Swain, J. E. (2011). Breastfeeding, brain activation to own infant cry, and maternal sensitivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A. , Nafziger, J. , & Nielsen, H. S. (2015). Behavioral economics of education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 115, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. S. , Aboud, F. , Mironova, E. , Vanilovich, I. , Platt, R. W. , Matush, L. , … Collet, J. P. (2008). Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFave, D. , & Thomas, D. (2017). Extended families and child well‐being. Journal of Development Economics, 126, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lutter, C. K. , & Lutter, R. (2012). Fetal and early childhood undernutrition, mortality, and lifelong health. Science, 337(6101), 1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccini, S. , & Yang, D. (2009). Under the weather: Health, schooling, and economic consequences of early‐life rainfall. American Economic Review, 99(3), 1006–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majid, M. F. (2015). The persistent effects of in utero nutrition shocks over the life cycle: Evidence from Ramadan fasting. Journal of Development Economics, 117, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. M. , Goodall, S. H. , Gunnell, D. , & Smith, G. D. (2007). Breast feeding in infancy and social mobility: 60‐year follow‐up of the Boyd Orr cohort. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92(4), 317–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi, A. , Lutter, R. , & Laxminarayan, R. (2017). Breastfeeding duration and adolescent educational outcomes: Longitudinal evidence from India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 38(4), 528–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees, D. I. , & Sabia, J. J. (2009). The effect of breast feeding on educational attainment: Evidence from sibling data. Journal of Human Capital, 3(1), 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, M. , Hardy, R. , & Wadsworth, M. E. (2002). Long‐term effects of breast‐feeding in a national birth cohort: Educational attainment and midlife cognitive function. Public Health Nutrition, 5(5), 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, D. S. (2013). Breastfeeding and children's early cognitive outcomes. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 919–931. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, J. , Witoelar, F. , & Sikoki, B. (2016). The fifth wave of the Indonesia family life survey: Overview and field report. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ewijk, R. (2011). Long‐term health effects on the next generation of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy. Journal of Health Economics, 30(6), 1246–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. , França, G. V. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Horta, B. L. , De Mola, C. L. , Quevedo, L. , Pinheiro, R. T. , Gigante, D. P. , … Barros, F. C. (2015). Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: A prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. The Lancet Global Health, 3(4), e199–e205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . (2016, October 6) Nine countries pledge greater investments in children, powering economies for long‐term growth [press release]. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2016/10/06/nine-countries-pledge-greater-investments-in-children-powering-economies-for-long-term-growth

- World Health Organization . (2010). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Part 1: Definitions. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information