Abstract

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) is an initiative designed to track country readiness and progress to effectively scale up breastfeeding programmes. BBF includes a policy toolbox that has three components: the BBF Index (BBFI), case studies, and a five‐meeting process. Mapping pathways of how BBF was implemented and utilized enables contextually grounded interpretation of its impact on breastfeeding outcomes. We conducted a programme impact pathways (PIP) analysis to identify pathways and critical quality control points (CCPs) by which BBF can enable changes in policy, legislation, and implementation of breastfeeding programmes. A BBF PIP diagram was developed, and CCPs were identified through a literature review and an iterative interviewing process with BBF investigators. The PIP was revised after feedback from BBF's Technical Advisory Group. BBF pretesting in Ghana and Mexico informed the formative evaluation of the PIP. PIP analysis identified relevant pathways between BBF activities and outcomes. Eight CCPs that could facilitate or attenuate BBF to fully impact the scaling up of the breastfeeding programmes were identified: (a) committee formed and trained; (b) committee understands BBF and BBFI; (c) committee's ability to acquire data; (d) BBFI scores; (e) criteria used for prioritizing recommendations; (f) dissemination of recommendations; (g) policymaker's reactions and media coverage; (h) committee's motivation and effective teamwork throughout BBF. Ghana and Mexico's pretesting of BBF confirmed the CCPs and provided valuable insights on potential mechanisms of BBF impacts at the country level. To further validate the PIP, a policy analysis framework is being tested in Ghana and Mexico.

Keywords: breastfeeding programs, complex adaptive systems, implementation science, process evaluation, program impact pathway, scaling up

Key messages.

Mapping how Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) is implemented and utilized enables contextually grounded interpretation of its results to help identify multi‐level factors to influence breastfeeding policies and outcomes.

The programme impact pathways analysis clearly identified BBF processes, activities, and outcomes and identified critical control quality points to facilitate enabling the environment for scaling up breastfeeding programmes.

A policy analysis study designed to understand the impact of BBF in enabling breastfeeding environments is being conducted in Ghana and Mexico.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding (BF) is an excellent investment for society at large and a key step towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (Rollins et al., 2016). However, BF prevalence remains low globally. Exclusive BF rates grew slowly from 24.9% in 1993 to 35.7% in 2013 (Victora et al., 2016). Strong evidence supports that providing a BF‐friendly environment where affordable and high‐quality BF protection, promotion, and support programmes can rapidly improve BF practices (Pérez‐Escamilla, Curry, Minhas, Taylor, & Bradley, 2012; Rollins et al., 2016). Nonetheless, countries have failed to generate the political will to invest in supporting mothers who wish to breastfeed (Lancet, 2017).

This missed opportunity requires an evidence‐based systems framework that guides and empowers countries to prioritize BF on the national agenda and guides investments in effective scaling up of BF programmes in the context of BF‐friendly environments (Pérez‐Escamilla & Moran, 2016). Without a clear systems framework, it is unlikely that a country will succeed in scaling up BF programmes, as such scale up requires extensive understanding of multisectoral strategies for implementation, adoption, and sustainability in complex contexts (Gillespie, Menon, & Kennedy, 2015; Menon, Rawat, & Ruel, 2013; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012; Pérez‐Escamilla & Moran, 2016). To fill this gap, the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) initiative was designed to assess country readiness and track progress accompanied by a policy development process to effectively scale up BF programmes across diverse socio‐economic, cultural, and health‐care systems contexts (Hromi‐Fiedler, Buccini, Gubert, Doucet, & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2019; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018).

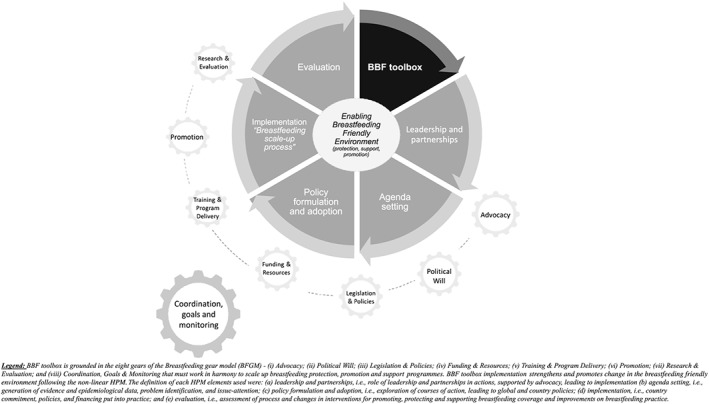

BBF is an initiative designed to guide countries in scaling up their national BF policies and programmes (see detailed description in Textbox 1 and Figure 1). The BBF initiative was implemented for its first time in Ghana (low‐middle income country) between June 2016 and February 2017 and, in Mexico (upper‐middle income country), between May 2016 and March 2017. Currently, BBF is being implemented in six additional low‐middle, upper‐middle, and high‐income countries—England, Germany, Myanmar, Samoa, Scotland, and Wales.

Textbox 1.

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly overview

|

BBF is an initiative designed to guide countries in scaling up their national breastfeeding policies and programmes. BBF is grounded in the Breastfeeding gear model (BFGM), which takes a complex adaptive systems approach to evidence‐based scaling up of breastfeeding policies and programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012). The BFGM posits that eight gears must work in harmony to achieve large‐scale improvements in scaling up a country's national breastfeeding friendly environment to protect, promote, and support optimal breastfeeding practices The theory of policy change behind BBF implementation is driven by the non‐linear heuristic policy model (HPM) which includes five elements: (a) leadership and partnerships (b) agenda setting; (c) policy formulation and adoption; (d) implementation; (e) evaluation, and (Darmstadt et al., 2014; Figure 1). To operationalize the BFGM into a useful resource for policymakers, BBF includes a toolbox to help countries assess, develop plans, and track breastfeeding scaling up in their specific contexts. The BBF toolbox has three main components: the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly index (BBFI), case studies, and a five‐meeting process that culminate with policy recommendations. The BBFI assesses the national readiness of countries to scale up breastfeeding policies and programmes. The case‐studies provide clear, evidence‐based real‐world examples to guide the BBFI scoring process as well as the translation of policy recommendations into action. The 5‐meeting process is the activity through which a country committee of breastfeeding and policies experts uses the BBFI and case‐studies to identify gaps, determine needs, plus develop and disseminate evidence‐based recommended actions to collectively advocate for the scaling up of breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support programmes. Although the BBF toolbox consists of a standard process and implementation design, its success relies on flexibility in implementation for diverse contexts. The implementation process of BBF is described in detail elsewhere (Hromi‐Fiedler et al., 2019). |

Figure 1.

The role of the BFGM and BBF toolbox in fostering policy changes to enable breastfeeding friendly environments. (Hromi‐Fiedler et al., 2019) BFGM: breastfeeding gear model; BBF: Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly

BBF is grounded in implementation science within the context of complex adaptive systems and the need to understand causal mechanisms and impact pathways of resulting policies and programmes to strengthen its impact and sustainability globally. Understanding how BBF works to achieve its outcomes and identifying factors that lead to variations in the reported success (i.e., effectiveness) or failure in its implementation are critical elements to be understood for successful BBF replication and utilization (Kim, Habicht, Menon, & Stoltzfus, 2011; Rawat et al., 2013; Rogers, 2000). Theory‐driven programme impact pathway (PIP) analysis was designed to assess programme implementation by explicitly mapping and assessing the mediating steps between programme inputs and outcomes following a causal logic (Rogers, 2000). Thereby, a PIP analysis helps to answer not only whether the impact was achieved but also how and why it was achieved (or not), accounting for the contextual factors that might influence the effectiveness of the intervention (Kim et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2014; Piwoz, Baker, & Frongillo, 2013; Rawat et al., 2013). Whereas for implementation science researchers, a PIP analysis can help design and explain findings from programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2016); for implementers, it can be crucial for identification of specific corrective actions and/or complementary interventions that are essential to programmatic success on a large scale (Avula et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2014; Pérez‐Escamilla, Segura‐Pérez, & Damio, 2014; Rawat et al., 2013; Slater, Lasco, Capelli, & Pen, 2014).

PIP analysis is more analytically and empirically powerful than traditional static evaluation frameworks such as the logic model and can lead to better programme design, evaluation questions, and programme impacts (Indig, Lee, Grunseit, Milat, & Bauman, 2017; Kim et al., 2011; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2014; Rogers, 2000). Mapping the pathways of how BBF is implemented and utilized can enable contextually grounded interpretation of its outcomes and identify factors and bottlenecks that might influence its global impact. Thus, we conducted a PIP analysis to identify pathways and critical quality control points (CCPs) by which BBF can enable changes in policy, legislation, and implementation of BF protection, promotion, and support programmes at the country level. Furthermore, we developed a policy analysis framework to be tested in Ghana and Mexico to understand the impact of BBF based on the PIP.

2. METHODS

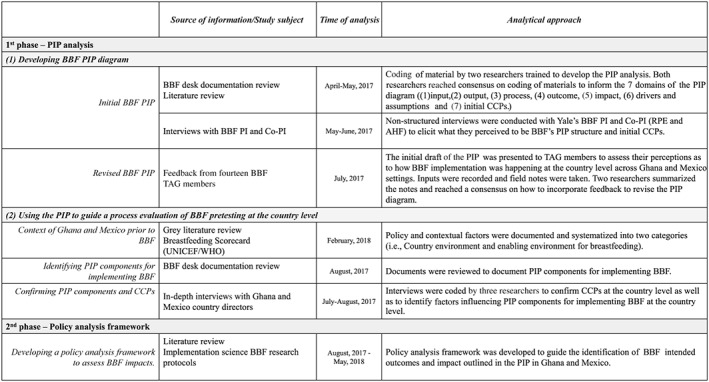

This study was conducted in two phases. First, we conducted a PIP analysis to identify and confirm pathways and CCPs. Second, we developed a policy analysis framework to assess the impact of BBF based on the PIP analyses. Figure 2 details the steps of each phase of the study as well as source of information, time, and analytical approach undertaken.

Figure 2.

Two‐phase methodology for conducting program impact pathways (PIP) analysis and developing the BBF policy analysis. BBF: Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly PI: Principal Investigator, CCPs: Critical quality control points, TAG: Technical Advisory Group

2.1. PIP analysis

We used a mixed methods approach to inform the BBF PIP analysis. The PIP analysis described in this paper refers to both Ghana and Mexico, both had completed BBF implementation at the time the PIP analysis was first developed. The PIP analysis was exempt from Human Subjects Approval by the Yale University Institutional Review Board because it did not involve human subjects' research.

Two steps were undertaken to conduct the BBF PIP analysis: (1) developing BBF PIP diagram and (2) using the PIP to guide a process evaluation of BBF pretesting at the country level.

2.1.1. Developing BBF PIP diagram

The logical sequence of the initial PIP diagram included seven domains (1) inputs, (2) outputs, (3) process, (4) outcomes, (5) impact, (6) drivers and assumptions, and (7) CCPs. Inputs consist of the components that need to be in place to start BBF implementation as well as planned BBF activities; outputs are the intended results of BBF implementation; processes are the components related to actions (i.e., execution of BBF activities at the country level); and outcomes and impact are the conceptualized components and mechanisms by which BBF impacts the process of translating policy recommendations into BF programmes as well as impacts on BF and maternal and child health outcomes. Drivers are factors that facilitate BBF implementation, and assumptions are conditions that need to be in place for this to happen. CCPs are crucial for understanding the set of indicators that need to be monitored to maximize the impact of BBF on policies and eventually BF outcomes and impact.

Initial BBF PIP

A PIP diagram specific to BBF was developed and included depictions of the mechanisms by which the BBF toolbox is expected to contribute to the intended outcomes (Rogers, 2000). The initial PIP was developed through: (a) a desk review of BBF documentation and a literature review of peer‐reviewed as well as grey literature of best practices of programme implementation and evaluation; and (b) interviews with Yale's BBF Principal Investigator (PI(R.P.E)) and Co‐PI(A.H.F.).

BBF document and literature review

A desk review of BBF documents included technical content (i.e., the operational manual and written guidance of BBF activities) as well as country‐level data from Ghana and Mexico (i.e., BBF Index [BBFI] scores, reports including meeting minutes, and notes detailing technical assistance provided to countries) informed the construction of the initial PIP for BBF. In addition, to guide the definition of each PIP component and identification of CCPs, a literature review was conducted by G. B. and K. H. to identify best practices of implementation of public health programmes and infant and young child feeding programmes. Information from this comprehensive document and literature review conducted between April and May 2017 informed the interviews with BBF's PI and Co‐PI.

Interviews with BBF PI and Co‐PI

Nonstructured interviews were conducted with Yale's BBF PI and Co‐PI to elicit what they perceived to be BBF's PIP structure. Both researchers were questioned about the purpose of BBF, how BBF works to achieve outcomes and impact; facilitators and barriers to achieve desired outcomes; and factors that influenced the quality of BBF implementation and sustainability, that is, potential CCPs. To gain an in‐depth understanding of challenges and opportunities within BBF implementation, they were also asked about the nature of the technical assistance provided to Ghana and Mexico for implementing BBF. Both researchers were interviewed at multiple points by G. B. and K. H. during the development of the PIP diagram. Inputs and feedback were incorporated into the PIP diagram during May and June 2017.

At the end of this process, a first version of the BBF PIP diagram was produced, and initial CCPs were identified (Data S1).

Revised BBF PIP

The PIP analyses and final PIP diagram involved a highly iterative process with key stakeholders. In July 2017, the initial draft of the PIP was presented by two co‐authors (G. B. and K. H.) to the BBF Technical Advisory Group (TAG) members, to assess their perceptions as to how BBF implementation occurred at the country level in Ghana and Mexico. The BBF TAG was composed of 14 stakeholders with collective expertise in BF as well as policy processes relevant to scaling up of health and nutrition programmes in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries from academia (Bangladesh, Canada, Ghana, Mexico, United Kingdom, and United States), international agencies (World Health Organization, Pan American Health Organization, and UNICEF), and international philanthropic and non‐profit organizations (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Alive & Thrive, The Manoff Group, Global Alliance to Improve Nutrition, Training and Assistance for Health and Nutrition). Inputs were recorded and field notes were taken. Two researchers (G. B. and K. H.) summarized the notes and reached a consensus on how to incorporate feedback to revise the PIP diagram and CCPs.

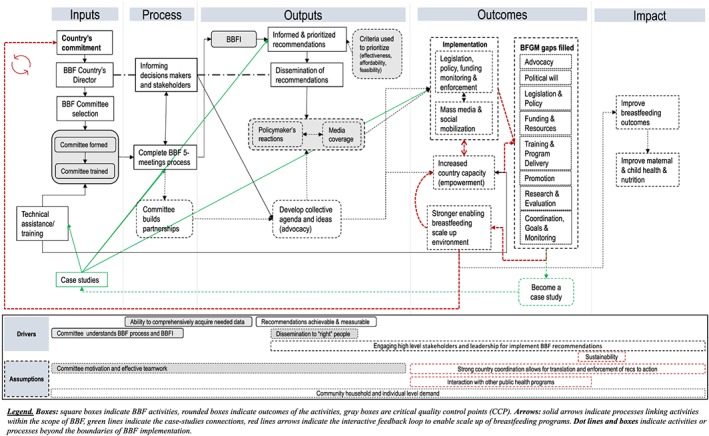

This process resulted in a final version of the BBF PIP diagram and identification of CCPs (Figure 3), and a corresponding narrative was developed. The final version of the BBF PIP diagram then was used to guide the process evaluation.

Figure 3.

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly program impact pathways (PIP) diagram. Final version

2.1.2. Using the PIP to guide a process evaluation of BBF pretesting at the country level

The purpose of the process evaluation was to obtain in‐depth information about how BBF was implemented at the country level.

Context of Ghana and Mexico prior to BBF

Ghana's and Mexico's policy and contextual factors were documented using several sources of evidence including economic, political, and health systems structures as well as demographic factors such as total population and births per year and infant mortality rates. The BF scorecard produced by UNICEF and the World Health Organization was used to document the BF‐enabling environment in both countries prior to BBF (UNICEF, WHO, & Global Breastfeeding Collective, 2017). Data were classified into two categories (i.e., country environment and enabling environment for BF) by G. B. to facilitate the understanding of the role of country context on BBF implementation (Pankaj & Emery, 2016), and final information was revised by country directors and coordinator.

Identifying PIP components for implementing BBF

BBF documents from Ghana and Mexico such as reports, BBFI scores, meeting minutes from each of the five‐meeting processes, policy briefs, and infographics were reviewed by G. B. and K. H. to confirm the PIP components for implementing BBF.

Confirming PIP components and CCPs

Ghana and Mexico country directors participated in in‐depth interviews to probe and confirm the role of each PIP component of the PIP diagram in the implementation of BBF at the country level and to identify additional emerging bottlenecks or CCPs along the intervention pathway and ways to resolve them. A pretested interview guide (Data S1) was used, and questions did not explicitly reference any specific PIP component. Interviews were conducted between July and August 2017 by a research assistant trained in qualitative methods (one interview was conducted in person and the other via Skype) and lasted approximately 75 min each. Both interviews were recorded and transcribed by a professional service. After receipt of the written transcripts, a member of the research team (G. B.) checked the written transcripts against the original audio recording to ensure accuracy. The interviews were coded by a subteam (G. B., K. H., and A. H. F.) to confirm CCPs as well as to identify factors influencing PIP components for implementing BBF at the country level. We used the developed PIP to guide the analysis of the transcripts and reach consensus on the main codes to confirm the PIP components. Similarities and differences in BBF implementation between the two countries were also identified and grouped to confirm the BBF PIP analysis.

2.2. Developing a policy analysis framework to assess BBF impacts

To unlock the BBF implementation “black box” (i.e., the operational mechanisms between BBF activities, process, outputs, and actual outcomes and impact), a policy analysis framework was developed to understand the impact of BBF on intended outcomes and impacts in Ghana and Mexico based on the PIP analysis. The framework considers the role BBF implementation may have in strengthening the BF‐enabling environments and seeks to (a) identify factors contributing to changes over time, including those needed to support policy formation and sustainability following the non‐linear heuristic policy model (HPM)—which includes five elements: leadership and partnerships agenda setting; policy formulation and adoption; implementation; and evaluation; (Darmstadt et al., 2014); and (b) understand the impact of BBF in strengthening the BF‐enabling environments in Ghana and Mexico to scale up BF policies and programmes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. PIP analysis

The results of the two steps undertaken to conduct the BBF PIP analysis are described in the following sections.

3.1.1. BBF PIP diagram

The BBF PIP analysis was summarized in a diagram mapping the pathways of the BBF inputs through the hypothesized processes, outputs, outcomes, and impacts considering key drivers and assumptions of the pathways. Directional links of how BBF inputs lead to process and outputs and to the intended outcomes and impact were imputed and refined through an iterative and consensus process with Yale's BBF PI and Co‐PI, generating a first version of the PIP (Data S1). The PIP was then revised based on feedback from experts of the BBF TAG. The revisions were as follows: (a) inclusion of the formation and training of BBF committee as a CCP; (b) inclusion of criteria for prioritizing recommendations as a CCP; (c) inclusion of high‐level stakeholders throughout the BBF process and leadership for implementing recommendations as a driver; and (d) inclusion of community household and individual‐level demand for BF support as an assumption (Figure 3).

TAG members' discussion around the PIP led to additional insightful observations including the following: (a) the unknown process by which policy recommendations are translated into BF programmes (i.e., barriers and facilitators to enforce the implementation), which was incorporated into the policy analysis framework; (b) what, if any, baseline conditions or minimum BF programmes need to be in place before a country is ready to scale up; (c) whether or not BBF would be the best tool to systematically monitor BF progress globally; and (d) the importance of continuing testing BBF in additional countries to better understand its outcomes on strengthening the enabling environment for BF scale up. These recommendations have been addressed through the reapplication of BBF in Ghana and Mexico and the launch of BBF in six additional countries across the globe.

The final BBF PIP outlines that a country's commitment to improve BF outcomes in combination with the technical assistance provided by BBF staff allows the country to select a country director and form a BBF committee. Strategies to train BBF committee members at the BBF first meeting and beyond can vary; however, it is critical to guarantee that the committee understands the BBF mission and vision, the BBFI, and the expectations of their involvement and commitment. Once the committee has been formed, the BBF five‐meeting process can be implemented. BBF case studies (defined in Textbox 1) are a key input and an outcome of the BBF that overlays across the pathways; the interaction of case studies with these pathways is highlighted throughout the BBF implementation.

The BBFI is the first BBF output used to develop informed recommendations that can be prioritized based on the country's context. The BBF fifth meeting is designed to disseminate the recommendations to high‐level stakeholders with an emphasis on policy decision makers. At this point, both policymaker reactions and mass media coverage can lead or contribute to the development of a collective agenda that can promote social mobilization to increase sound investments needed to implement cost‐effective BF policies and programmes on a large scale. Additionally, committee members' participation in BBF also supports a country's increased capacity to build intersectoral partnerships, especially as a result of ongoing communications with decision makers and key stakeholders about the BBF process, gaps being identified and recommendations being proposed.

As an outcome, these paths lead to enacted legislation and policies to promote, protect, and support BF. This political‐policy axis in turn drives the funding and resources needed to support fulfilment of the gaps. Research and evaluation are needed to sustain goal setting and to generate evidence for strengthening coordination and advocacy. This immediate outcome can influence the country's capacity and empowerment. Through strong country coordination, the translating and enforcing of BBF recommendations can occur and lead to actions that fill gaps on each gear of the BF gear model (gaps that were identified by the BBFI), thus resulting in a stronger enabling environment to scale up BF.

BBF impact on a sustainable BF scaling up process requires country coordination including attention to integrating other public intersectoral programmes to ultimately promote the impact on BF, maternal and child health and nutrition outcomes.

The final BBF PIP analysis identified eight CCPs for BBF country level impact: (a) committee formed and trained; (b) committee understands BBF and BBFI; (c) committee's ability to comprehensively acquired data needed; (d) BBFI scores; (e) criteria used by the committee for prioritizing recommendations; (f) dissemination of recommendations to the right people; (g) policymaker's reactions and media coverage; and (h) committee's motivation and effective teamwork throughout BBF (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Matrix with PIP component definition, CCP confirmed by Ghana and Mexico pretesting of BBF implementation at the country level

| PIP domain | PIP components | Definition | CCP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Country's commitment | Country's commitment can vary for each context. The evidence on the current BF‐ enabling environment, including suboptimal BF practices, a national policy window and the governance structure will define the size of the challenges to create and sustain a momentum. | |

| Country's director and coordination team | Director understanding of BBF mission and vision is critical. Country coordination team plays a leadership role to facilitate, encourage and enable stakeholders to work together effectively. Antecedent conditions, system context and collaborative/mutual goals will influence the teamwork dynamic. | ||

| Committee selection | Institutional design of BBF committee composition, i.e., basic protocols and rules for establishing the committee (individuals and institutions). | ||

| Starting conditions of power/resources balance means the capacity, organization, status or resources to participate, or to participate on an equal footing with other stakeholders. | |||

| Committee formed and trained | Strategies used to train BBF committee members at the 1st meeting and beyond | X | |

| Driver: Committee understands BBF and BBFI | X | ||

| Technical assistance | Technical assistance (TA) to country's director aims to build capacity to enable, empower and strengthen BBF implementation. | ||

| Case studies | Usefulness of case studies and examples for experimental learning of committee members in the BBF process and how much they feel that it has guided the development of post‐assessment recommendations | ||

| Usefulness of case studies for the experimental learning of policymakers in the formulation and implementation of legislations, policies, programmes and trainings | |||

| Process | Informing decision makers throughout BBF process | Developing a shared understanding, partnership and actor‐network cohesion in relation to BF agenda, ideas and needs. | |

| Complete 5‐meeting process | Building the momentum through collaborative governance, i.e., model of governance that brings multiple stakeholders in common forums with public agencies to engage in consensus‐oriented decision marking. | ||

| Process/ output |

Committee builds partnerships and Develop collective agenda and ideas |

Two or more sectors or individuals establish collaboration and develop mechanisms to support interactions and reach mutual agreement to develop collective agenda and work together to move forward. | |

| Outputs | BBFI | Ability of committee members to generate data and evidence on BF environment by scoring the benchmarks following the BBF methodology | X |

| Driver: Ability to comprehensively acquired data needed | X | ||

| Informed and prioritized recommendations |

Recommendations reflect gaps identified by the BBFI and are developed to be achievable and measurable. Driver: Recommendations are achievable and measurable |

||

| Criteria used for prioritizing recommendations | Criteria used to prioritize are evidence‐based, considering options of policies and interventions that are likely to impact in the country‐context. | X | |

| Dissemination of recommendations |

Strategic communication, advocacy and social mobilization through planned events to engagement stakeholders including the BBF 5th meeting. Driver: Engaging high level stakeholders and leadership for implement BBF recommendations |

||

| Driver: Dissemination to the right people | X | ||

| Policymaker's reactions and media coverage | Engagement of key high‐, mid‐, local‐level actors and media outlets measured by the level of coverage based on the time spent on coverage. | X | |

| Outcomes |

Implementation and BFGM gaps filled and Enable BF scale up environment |

“Black box of implementation” how the decision to implement the BBF recommendations at the organizational/ community/ national level happens. It will be dependent on country‐level of “readiness” and preparedness for scaling up while considering competing priorities, funding and resources. | ** |

| Governance intersectoral structure with a strong network (i.e. civil society, donors and private sector) committed with clear strategies and vision of gaps and needs can facilitate the cooperation for addressing BFGM gaps and scaling up | ** | ||

| Become a case study | Drawing upon case studies of countries that have experienced some success in enabling the BF environment. Country's quantitative, statistical analyses and qualitative analysis, process‐oriented research can, be combined to generate a powerful narrative of change. | ||

| Impact |

Improve BF outcomes and improve maternal and child health and nutrition outcomes |

Evidence on improvements on BF practices and other health and nutrition outcomes post BBF assessment due to the implementation of recommendations within 3 years. | |

| Assumptions | Committee motivation and effective teamwork | Reasons for participation and shared understanding are critical to develop collaborative governance and commitment to maintain motivation. | X |

| Strong country coordination allows for translation and enforcement of recommendations to action | Strong country coordination to translate and enforce recommendations into actions, including take advantage of national policy window (e.g. government changing) and interact with other public health programmes | ||

|

Sustainability and Interaction with other public health programme |

Country uptake BBF as a monitoring tool, including horizontal and vertical coordination with the right people (i.e., high level stakeholders) in the right ways to track financial and resource mobilization to sustain commitment beyond BBF process. | ||

| Community household and individual level demand | Demand and needs of population in relation to BF are addressed by fulfilling the gaps identified in the BBF process. |

Note: Legend “X” means CCP confirmed in Ghana and Mexico pretesting. “**” means components that are being assessed by ongoing research framework. CCP: critical quality control point; PIP: programme impact pathway.

3.1.2. Process evaluation of BBF pretesting at the country level guided by the PIP

The contexts in Ghana and Mexico prior to BBF, including country environment and BF‐enabling environment, varied widely (Table 2). Ghana's and Mexico's experiences implementing BBF are further described in previous publications (Aryeetey et al., 2018; Gonzalez de Cosio, Ferre, Mazariegos, & Perez‐Escamilla, 2018).

Table 2.

Process evaluation of “real‐world” pretesting of BBF implementation in Ghana and Mexico, 2016

| Country context prior to BBF | Ghana | Mexico |

|---|---|---|

| Country environment a , b , c , d | ||

| Economic and region | Low‐middle income country located in West Africa. | Upper‐middle income country located in Latin America and Caribbean region. |

| Political system | Ghana is a unitary republic with an executive presidency and a multiparty political system. Administratively, Ghana is divided into 10 regions with 216 districts. Each region has a regional coordinating council headed by a regional minister appointed by the president who coordinates the activities of districts under their jurisdiction. | The United Mexican States are a federation whose government is representative, democratic and republican based on a presidential system. The constitution establishes three levels of government: The federal union, the state governments and the municipal governments. |

| Health system structure | Ghana has a universal health‐care system strictly designated for Ghanaian nationals, National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). All Ghanaian citizens have the right to access primary health care. | State‐funded institutions such as Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) and the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE) play a major role in health and social security. Private health services are also very important and account for 13% of all medical units in the country. |

| Demographic | As of 2016, Ghana had a population of 28,206,728 with approximately 460,000 births per year. | As of 2015, Mexico had a population of 119,938,473 with 2,293,708 births per year. |

| Infant mortality | Infant mortality prevalence under 5 years is 58.8 deaths/1,000 live births. | Infant mortality prevalence under 5 years is 14.6 deaths/1,000 live births. |

| Enabling environment for breastfeeding (BF) e | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates | From 2008 to 2014 EBF rates declined from 63% to 52%. | From 2006 to 2012 EBF rates declined from 22.3% to 14.4% especially in rural areas (36.9% to 18.5%). |

| Amount of donor funding for BF | $2 was allocated per child by donor funding in 2013. | $0 was allocated per child by donor funding in 2013. |

| Status of ten steps of BF | No official data on % of births occur in baby friendly hospitals and maternities. | 3.5% of births occur in baby friendly hospitals and maternities. |

| Status of code implementation in legislation | Full provisions in law: Countries have enacted legislation or adopted regulations, decrees or other legally binding measures encompassing all or nearly all provisions of the code and subsequent WHA resolutions. | Many provisions in law: Countries have enacted legislation or adopted regulations, decrees or other legally binding measures encompassing many provisions of the code and subsequent WHA resolutions. |

| Status of paid maternity leave | Legislation mandates 12 weeks of maternity leave with 100% of previous earnings paid for by employer funds. | Legislation mandates 12 weeks of maternity leave with 100% of previous earnings paid for by social funds. |

| Percent of primary health‐care facilities offering individual IYCF counselling | 100% of primary health‐care facilities offer individual IYCF counselling. | No data available of proportion of primary health‐care facilities that offer individual IYCF counselling. |

| Percent of districts offering community BF programmes | 100% of districts implement community‐based nutrition, health, or other programmes with IYCF counselling. | No data available on districts implementing community‐based nutrition, health, or other programmes with IYCF counselling. |

| PIP components for implementing BBF f | ||

| Country's commitment | ||

| Process of commitment to BBF | Director introduced BBF to Ghana Health Services through multiple meetings. Both partnered to select BBF committee members. | Director was historically engaged with multiple BF activities within the country. The director introduced BBF to the National BF Forum (a group of key stakeholders including other academics, civil society and government) who supported the implementation of BBF. |

| Time to initiate first meeting (months) | 11 months | 10 months |

| Country director and coordination team | ||

| Sector of the director profile and number of hours per week devoted to BBF | Director is from academia and has devoted approximately 12‐hours per week to implement BBF. | Director is from academia and devoted approximately 2‐hours per week to implement BBF. |

| Motivation to engage on BBF | Member of technical advisory group of BBFI development | Member of technical advisory group of BBFI development |

| Paid human resources involved in implementing BBFg | A research assistant devoted 30 hours per week and an administrative assistant dedicated 5 hours per week. | A project coordinator devoted 40 hours per week and a research assistant dedicated 40 hours per week. |

| Committee selection | ||

| Composition of committee | 12‐member (three academics, six government, and three international organizations such as UNICEF, USAID, and WHO) | 11‐member (two academics, two academics advisors to government, three government, three civil society, and one international organization, i.e., Save the Children) |

| Starting conditions | Consultation with the Ghana health service under the leadership of the University of Ghana. | Consultation with BF experts in Mexico under the leadership of the Universidad Iberoamericana. |

| Committee formed and trained | ||

| Training | Training on BBF scoring process at first meeting by director. | Training on BBF scoring process at first meeting by director, coordinator and BBF staff as technical assistance. |

| Technical assistance to BBF director | ||

| Provider of technical assistance | Senior researcher involved in developing BBF programme followed up the whole implementation with two sites visits, real‐time guidance, providing tools and templates and a technical manual. | Senior researcher involved in developing BBF programme followed up the whole implementation with two sites visits, real‐time guidance, providing tools and templates and a technical manual. |

| Case studies | ||

| Usefulness of case‐studies | Not fully used by committee members | Not fully used by committee members |

| Informing decision makers throughout BBF process | ||

| Strategies used to engage stakeholders | Consultation visits to key decision makers (UNICEF: country director; WHO: country representative; Ghana Health Service: director of family health) | Face to face meetings were conducted by the coordination team with key stakeholders (UNICEF: country director) |

| Complete five‐meeting process | ||

| Time to complete (months) | May 2016 to February 2017 | June 2016 to April 2017 |

| BBFI | ||

| BBF Total score | Moderate‐to‐strong environment for scaling up BF programmes (2.0 out of a maximum of 3.0). | Weak‐to‐moderate environment for scaling up BF programmes (1.4 out of a maximum of 3.0). |

| Informed and prioritized recommendations | ||

| Prioritization of BBF recommendations | Director led the prioritization process with the input from the committee, reaching consensus on recommendations via email between the fourth and fifth meeting | Mexico committee reached face‐to‐face consensus at the fourth meeting on priorities recommendations |

| Key recommendations |

1. Strengthen advocacy by enlisting more BF champions (high level and visible individuals); engage with existing champions and build their capacity 2. Ratify and adopt provisions of ILO Maternity Protection Convention, 2000, No. 183 3. Harmonize, strengthen, and monitor preservice and in‐service training of health staff and volunteers providing BF services 4. Scale up dissemination of accurate information on BF practice using multiple channels of communication at all levels |

1. Motivate decision‐makers to develop effective breast‐ feeding programmes and policies through civil society advocacy 2. Advocate with high‐level public officials to keep BF in public agenda 3. Use regulatory instruments to limit risk to breast‐ feeding protection, promotion and support 4. Identify and support financial and human resources train on BF protection, promotion, and support, and research, monitoring and evaluation 5. Implement BF policies and actions via trained personnel 6. Reach entire population including women employed in informal economy 7. Implement comprehensive surveys and health‐care information systems 8. Develop strategy for implementing the national policy on BF |

| Dissemination of recommendation | ||

| Strategies used to disseminate BBF recommendations | Ghana held a fifth and sixth meetings for disseminating the key recommendations, one with a technical staff and another with high level decision makers. In both meetings, there was strong media coverage. Specific materials were produced for dissemination (e.g., policy briefs, infographic) | Mexico held a fifth call to action with strong involvement from civil society and media coverage. Specific materials were produced for dissemination (e.g., policy briefs, infographic) |

| Committee builds partnerships and develops collective agenda and ideas | ||

| Examples of activities emerging after BBF | A social media campaign prototype was subsequently developed in response to recommendations. Messages were developed and translated into visual format with input from the BBF committee. The materials informed the development of Breastfeed4Ghana, a social media campaign in Ghana aimed to strengthen breastfeeding support through advocacy, harness support for maternity protection laws, and implement more effective dissemination of accurate actionable information about breastfeeding across Ghana through cost‐effective and innovate social media platforms. | In response to a major earthquakes in Mexico of September 2017, the BBF committee members lead a task force to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. Multiple coordinated activities were developed including advocacy against formula donation, and free support from lactation consultants through WhatsApp. Evaluation of these activities was conducted to inform the development of an action plan to protect breastfeeding in future emergency situations. |

Data sources:

The World Bank Group, 2018. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Ghana Statistical Services. Available at: http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/pop_stats.html

Mexico National Institute of Geography and Demography. Available at: http://en.www.inegi.org.mx/

Global Health Observatory data. Infant Mortality. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/neonatal_infant_text/en/

Global breastfeeding scorecard. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf?ua=1

BBF documentation.

The hours per week devoted are an estimation based on the report from BBF Director in Ghana and BBF project coordinator in Mexico.

Countries directors' perspectives on the PIP components for implementing BBF confirmed the CCPs and many of the PIP components described in the PIP diagram (Figure 3 and Table 1). Similarities and differences were grouped into PIP components as detailed in the diagram for implementing BBF (Table 2), and factors influencing BBF implementation were identified. In summary, countries directors' perspectives showed that some level of awareness on suboptimal BF practices are needed to generate the momentum for garnering the support from government and non‐governmental actors to support the implementation of BBF. Ghana and Mexico country directors and coordination team worked in full cooperation with government officials to allow access to key informants and data to accurately score the BBFI. The country director and coordination team played a leadership role in facilitating committee members to work together effectively as well as in encouraging and enabling the development of partnerships with the right stakeholder to strengthen intersectoral governance structure. BBF committee selection including institutional composition and starting conditions of power and balance were also identified as a factor influencing BBF implementation. Ghana and Mexico directors highlighted that these two components can influence committee member motivation and effective teamwork throughout BBF implementation. For countries directors, technical assistance and training provided by the BBF staff had cultivated and supported leadership for country‐driven BBF implementation. Another factor indicated by countries directors during in‐depth interviews was that the successful completion of the five‐meeting process was dependent on a systematic and comprehensive methodology for gathering the available data and the ability of the BBF committee to comprehensively acquire these data to generate the BBFI scores. Finally, Ghana and Mexico experiences indicated that the dissemination of BBF recommendations at the fifth meeting must include strong media coverage to facilitate engagement from high‐level stakeholders. Lastly, BBF case studies were not fully used during pretesting of BBF.

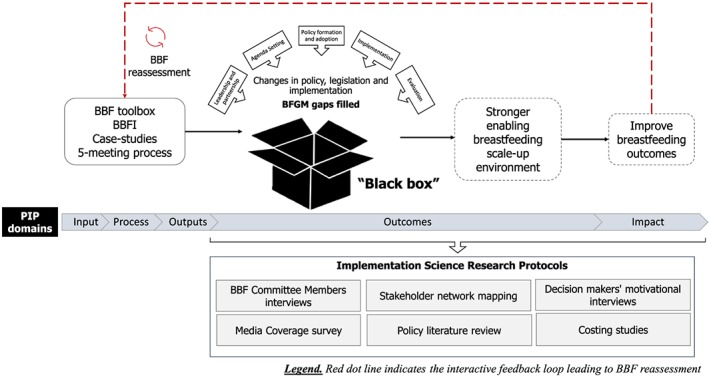

3.2. Policy analysis framework to assess BBF outcomes

The policy analysis framework is described in Figure 4. The BBF toolbox, composed of the BBFI, case studies, and five‐meeting process, drives the HPM policy‐making process. Leadership and partnerships supported by advocacy are required to move the BBF‐proposed recommendations to actions leading to both agenda setting and implementation. Country commitment with BF programmes implementation will lead to the development of a plan of action including the formulation and adoption of policies and financing that will be put into practice. Evaluation and assessment of process and changes in interventions for promoting, protecting, and supporting BF are crucial to identify improvements on BF practice as well as further gaps and needs. A unique feature of the BBF toolbox is that it can be adopted by countries as a monitoring tool to reassess their progress and gaps.

Figure 4.

Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) policy analysis framework to assess if and how BBF leads to changes in policies, legislation, and implementation to enable breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support

Implementation research protocols were developed to assess if and how BBF leads to changes in policies, legislation, and implementation. These protocols also assess which aspects of the HPM policy‐making process embedded into the BBF process of change are needed to achieve the intended outcomes and impact on the BF‐enabling environment outlined in the PIP (Textbox 2). These protocols are currently being applied in Mexico and Ghana to confirm the framework and the PIP outcomes and impacts.

Textbox 2.

Implementation science research protocols used to “unlock” the changes and challenges in enabling breastfeeding environment and related HPM elements assessed for each protocol

|

1) Committee member interviews aimed to understand BBF committee members' experiences, lessons learned and key recommendations for decision makers to evaluate and improve the BBF toolbox and facilitate its implementation at the country level. Main HPM elements assessed: Leadership and partnerships and agenda‐setting. 2) Stakeholder network mapping aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the stakeholders involved in the decision‐making of breastfeeding within each country to translate evidence‐based recommendations into action. Main HPM elements assessed: Agenda‐setting as well as policy formation and adoption. 3) Motivational interviews with decision makers aimed to identify the factors involved in or influencing the decision‐making process of high‐level individuals with the power (i.e. level of influence) to make changes recommended by the country BBF committee. Main HPM elements assessed: Agenda‐setting and implementation. 4) Media survey and policy review aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the changes (advances and performance) involving breastfeeding within each country and to identify opportunities to enable policy and governance that will strengthen the breastfeeding environment. Through a documentation of media coverage and policy changes in breastfeeding within Mexico and Ghana over the past year. Main HPM elements assessed: Policy formation and adoption and implementation. 5) Costing framework for breastfeeding programmes aimed to develop a costing methodology for (a) extension of maternity‐leave to formal workers and implementation of social protection maternity leave for the informal workers and (b) scaling up of baby‐friendly hospital initiative (BFHI). Main HPM elements assessed: Agenda‐setting, policy formation and adoption, and implementation. 6) BBF reassessment aimed to access progress and changes in the breastfeeding enabling environment after 18 months following the first BBF assessment. Main HPM elements assessed: Evaluation, leadership and partnerships and agenda‐setting. |

4. DISCUSSION

The BBF PIP systematically mapped pathways and important mediating mechanisms of how BBF is implemented to achieve clearly defined outcomes and impact. The PIP analysis identified the essential components of BBF required for its widespread replication globally and to monitor whether BBF was delivered successfully at the country level. Previous evidence‐based approaches to design large‐scale programmes have shown that a theory‐driven framework with intentional and guided efforts to achieve its impact is needed to systematically understand the success of implementation of a programme or initiative (Baker, Sanghvi, Hajeebhoy, Martin, & Lapping, 2013; Nguyen et al., 2014; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2014; Slater et al., 2014) such as BBF.

Our findings from the PIP analysis underscore the key role of CCPs and a support system that might facilitate the successful implementation of BBF to achieve the fully intended outcomes on enabling or strengthening the BF scale‐up environment. Three CCPs are directly related with the activities related to country committee members, confirming that the BBF country committee serves as the foundation of BBF implementation and indicating that BBF implementation needs to be driven by strong in‐country leadership reflecting strong country commitment to start and successfully complete the BBF process (Hromi‐Fiedler et al., 2019). Evidence of the need for strong individual and institutional leadership to increase political commitment to BF has previously been highlighted (Swanson et al., 2012; UNICEF, 2013). Moreover, the successful implementation of BBF relies on committee members who hold high‐level positions and whose leadership is valued both within and outside of their institutions (Hromi‐Fiedler et al., 2019; Safon, Buccini, Eguiluz, González de Cosio, & Pérez‐Escamilla, 2018). Indeed, findings from in‐depth interviews with Mexico's BBF committee members suggest that strong leadership from a committee coordinator is needed to sustain effective teamwork, thus creating positive group dynamics that can foster trust and commitment among members (Safon et al., 2018). Research shows that team dynamics as well as team's motivations can influence the effectiveness of programme implementation strategies (Sarkies et al., 2017). This reinforces the importance of the CCP that calls for committee members to be trained on and fully understand the BBF process. These findings are important given that policy formation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation elements embedded into the BBF policy analysis framework can only occur after problem identification and agenda setting take place after a shared vision of change is established (Sarkies et al., 2017).

Having evidence‐based metrics, such as those derived from the BBFI, are likely to help develop effective context‐specific recommendations to effectively implement programmes on a large scale (Fox, Balarajan, Cheng, & Reich, 2015; Moran et al., 2012; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018). Therefore, the CCPs are key to identify monitoring indicators. Engaging key actors and policymakers during this process is needed to facilitate change based on an evidence‐informed process (Sarkies et al., 2017). Furthermore, the use of evidence‐based criteria to reach consensus on the priority recommendations is a CCP as evidence has shown that it can facilitate to improve better governance by ensuring that all actors/committee members invest in the process, fostering a sense of process ownership along the way (Rudan et al., 2017). Dissemination of priorities recommendations among decision makers or influencers and allowing them to react to them may also help maximize the BBF policy impacts (Moat, Lavis, Clancy, El‐Jardali, & Pantoja, 2014).

Patterns identified through Ghana and Mexico's pretesting of BBF strongly support the conceptualized components and pathways in the PIP. However, how BBF will achieve its impact will vary depending on the country context and readiness to scale up BF interventions. For instance, Ghana has an overall moderate‐to‐strong enabling BF environment (Aryeetey et al., 2018), which means that the country has the foundation to scale up BF interventions and funding commitments are critical to implement BBF‐recommended actions and for BBF to achieve its impact. On the other hand, Mexico has an overall weak‐to‐moderate enabling environment (Gonzalez de Cosio et al., 2018), which means that several steps are needed before funding becomes the unique critical tipping point to advance the scale up of BF programmes. In Mexico, the development of a shared agenda and setting the priorities is critical. Evidence has shown that agenda setting alongside with domestic funding drives programming, resulting in increases in coverage of interventions and, ultimately, improves outcomes (Darmstadt et al., 2014; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012). In reality, it is well recognized that policy progress is rarely linear, and many changes might occur at once, because a particular input might often address more than one element in the process of change (Darmstadt et al., 2014; Moloughney, 2012). Thus, an adequate assessment of gaps in a country's BF environment can lead to diverse opportunities to accelerate progress all along the path to impact, which will depend heavily on the context, funding commitments, and windows of opportunity at the country level.

By analysing the pretesting in Ghana and Mexico, we refined and expanded the knowledge of process and contextual mechanisms for the success of BBF implementation at the country level. Likewise, the complex adaptive nature of BBF implementation at the country level with multiple feedback loops (i.e., when an output of a process within the system feeds back as an input into the same system), path dependence (i.e., even when processes have similar starting points may end up being implemented through different pathways because of bifurcations and choices made along the implementation process), and phase transitions (i.e., when radical changes take place in the features of system parameters as they reach certain critical or tipping points) calls for flexible mechanisms and pathways to implement BBF successfully at the country level. These findings strengthen the plausibility that the PIP provides insights on how BBF implementation can be improved to ultimately impact countries globally. It also contributes to the dearth of literature on implementation science studies focusing on BF initiatives, a key priority area in public health given the significance of optimal BF practices for child survival, health, and development outcomes.

The analysis of the presented PIP is limited in its generalization, as this reflects the pioneer pretesting experience undertaken by Ghana and Mexico. Indeed, further research is needed to understand to what extent the PIP components and CCPs are empirically associated with BBF success on changing BF outcomes based on the policy framework developed for this purpose. Acknowledging the complex adaptive nature within the PIP (Paina & Peters, 2012), current experience implementing BBF from a larger sample of countries has allowed us to further investigate the role of facilitators and barriers of BBF impact. On the other hand, lessons learned from Ghana and Mexico pretesting experiences documented the complex adaptive nature of BBF implementation. The identified pathways are not necessarily linear, with complex adaptive behavior such as feedback loops, path dependence, phase transitions, occurring all along the implementation process and depending heavily on multiple country context factors. Likewise, how a country gets from one component to another in the PIP may differ greatly depending on the context and the performance of drivers and assumptions. Moreover, the lessons learned from Ghana and Mexico pretesting allowed for the streamlining of the BBF toolbox by providing further guidance and standardizing methods to implement BBF across countries (Hromi‐Fiedler et al., 2019) increasing the potential to achieve BBF outcomes and impact.

The PIP analysis identified essential components for BBF implementation, replication, and scale up globally. Pretesting of the PIP analysis in Ghana and Mexico confirmed the CCPs and provided valuable insights on potential mechanisms of BBF impacts at the country level. Implementation science research currently being conducted in Ghana and Mexico guided by the BBF policy analysis framework (Figure 4) will help advance the understanding of how BBF helps translate policy recommendations into actions to scale up BF programmes in the context of the complex adaptive systems “Breastfeeding Gear Model” (Perez‐Escamilla et al., 2012).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

GB, KLH, and RPE designed the initial PIP and led its subsequent revisions. GB, KLH, and AHF conducted data analysis and interpretation of results. GB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and KLH, AHF, and RPE revised it critically through an iterative process. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the BBF directors of Ghana and Mexico, Dr Richmond Nii Okai Aryeetey and Dr Teresita del Niño Jesús González De Cosio Martínez, respectively, for their insightful input. We further acknowledge Ms Isabel Ferre Eguiluz for her valuable feedback about BBF implementation in Mexico, Ms Grace Carroll for conducting the in‐depth interviews with BBF countries' directors, and Ms. Cara Safon for her feedback on the interview guide. We also thank the BBF TAG members for their valuable feedback on the preliminary results of the BBF PIP analysis.

Buccini G, Harding KL, Hromi‐Fiedler A, Pérez‐Escamilla R. How does “Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly” work? A Programme Impact Pathways Analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12766 10.1111/mcn.12766

REFERENCES

- Aryeetey, R. , Hromi‐Fiedler, A. , Adu‐Afarwuah, S. , Amoaful, E. , Ampah, G. , Gatiba, M. , … Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2018). Pilot testing of the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly toolbox in Ghana. International Breastfeeding Journal, 13, 30 10.1186/s13006-018-0172-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avula, R. , Menon, P. , Saha, K. K. , Bhuiyan, M. I. , Chowdhury, A. S. , Siraj, S. , … Frongillo, E. A. (2013). A program impact pathway analysis identifies critical steps in the implementation and utilization of a behavior change communication intervention promoting infant and child feeding practices in Bangladesh. The Journal of Nutrition, 143, 2029–2037. 10.3945/jn.113.179085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J. , Sanghvi, T. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Martin, L. , & Lapping, K. (2013). Using an evidence‐based approach to design large‐scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34, S146–S155. 10.1177/15648265130343S202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmstadt, G. L. , Kinney, M. V. , Chopra, M. , Cousens, S. , Kak, L. , Paul, V. K. , … Lawn, J. E. (2014). Who has been caring for the baby? Lancet, 384, 174–188. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60458-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, A. M. , Balarajan, Y. , Cheng, C. , & Reich, M. R. (2015). Measuring political commitment and opportunities to advance food and nutrition security: Piloting a rapid assessment tool. Health Policy and Planning, 30(5), 566–578. 10.1093/heapol/czu035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S. , Menon, P. , & Kennedy, A. L. (2015). Scaling up impact on nutrition: What will it take? Advances in Nutrition, 6, 440–451. 10.3945/an.115.008276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez de Cosio T., Ferre I., Mazariegos M. & Perez‐Escamilla R. (2018) Scaling up breastfeeding programs in Mexico: Lessons Learned from the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Initiative. Curr Dev Nutr 2, nzy018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hromi‐Fiedler A., Buccini G.S., Gubert M.B., Doucet K. & Pérez‐Escamilla R. (2019). Development and pre‐testing of ‘Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly’: Empowering governments for global scaling up of breastfeeding programs. Matern Child Nutr, 15:e12659. 10.1111/mcn.12659 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Indig, D. , Lee, K. , Grunseit, A. , Milat, A. , & Bauman, A. (2017). Pathways for scaling up public health interventions. BMC Public Health, 18(68). 10.1186/s12889-017-4572-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.S., Habicht J.‐P., Menon P. & Stoltzfus R.J. (2011) How do programs work to improve child nutrition? Program impact pathways of three nongovernmental organization intervention projects in the Peruvian Highlands. IFPRI discussion paper 01105.

- Lancet (2017). Breastfeeding: A Missed Opportunity for Global Health. Editorial. The Lancet 390 352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Menon, P. , Rawat, R. , & Ruel, M. (2013). Bringing rigor to evaluations of large‐scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding and nutrition: The evaluation designs for the Alive & Thrive initiative. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3 Suppl), S195–S211. 10.1177/15648265130343S206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moat, K. A. , Lavis, J. N. , Clancy, S. J. , El‐Jardali, F. , & Pantoja, T. (2014). Evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues: Perceptions and intentions to act on what was learnt. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92(1), 20–28. 10.2471/BLT.12.116806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloughney B. (2012). The use of policy framework to understand public health‐related public policy process: A literature review. (ed Peel Public Health). Available at: https://www.peelregion.ca/health/library/pdf/Policy_Frameworks.PDF

- Moran, A. C. , Kerber, K. , Pfitzer, A. , Morrissey, C. S. , Marsh, D. R. , Oot, D. A. , … Shiffman, J. (2012). Benchmarks to measure readiness to integrate and scale up newborn survival interventions. Health Policy Plan, 27(Suppl 3), iii29–iii39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H. , Menon, P. , Keithly, S. C. , Kim, S. S. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Tran, L. M. , … Rawat, R. (2014). Program impact pathway analysis of a social franchise model shows potential to improve infant and young child feeding practices in Vietnam. The Journal of Nutrition, 144, 1627–1636. 10.3945/jn.114.194464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paina, L. , & Peters, D. H. (2012). Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning, 27, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankaj V. & Emery A.K. (2016). Data placemats: A facilitative technique designed to enhance stakeholder understanding of data. In: Evaluation and Facilitation. R. S. Fierro, A. Schwartz & D. H. Smart (Eds.), New Directions for Evaluation.

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Curry, L. , Minhas, D. , Taylor, L. , & Bradley, E. (2012). Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low‐ and middle‐income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Advances in Nutrition, 3, 790–800. 10.3945/an.112.002873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Hromi‐Fiedler, A. J. , Gubert, M. B. , Doucet, K. , Meyers, S. , & Buccini, G. S. (2018). Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index: Development and application for scaling‐up breastfeeding programmes globally. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14 10.1111/mcn.12596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla R., Lamstein S., Isokpunwu C., Adeyemi S., Kaligirwa C. & Oni F. (2016). Evaluation of Nigeria's community infant and young child feeding counselling package, report of a mid‐process assessment. In: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project. (ed V. Arlington). Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, and UNICEF.

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , & Moran, V. H. (2016). Scaling up breastfeeding programmes in a complex adaptive world. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12, 375–380. 10.1111/mcn.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Segura‐Pérez, S. , & Damio, G. (2014). Applying the Program Impact Pathways (PIP) evaluation framework to school‐based healthy lifestyles programs: Workshop evaluation manual. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35, S97–S107. 10.1177/15648265140353S202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz, E. , Baker, J. , & Frongillo, E. A. (2013). Documenting large‐scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding is key to facilitating progress in child nutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3): 3_suppl2), S143–S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, R. , Nguyen, P. H. , Ali, D. , Saha, K. , Alayon, S. , Kim, S. S. , … Menon, P. (2013). Learning how programs achieve their impact: Embedding theory‐driven process evaluation and other program learning mechanisms in alive & thrive. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34, S212–S225. 10.1177/15648265130343S207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P. J. (2000). Program theory: Not whether programs work but how they work In Models E. (Ed.), S.D. I., M.G. F. & K. T. Boston: Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Victora, C. G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387, 491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudan, I. , Yoshida, S. , Chan, K. Y. , Sridhar, D. , Wazny, K. , Nair, H. , … Cousens, S. (2017). Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: VII. A review of the first 50 applications of the CHNRI method. Journal of Global Health, 7(1), 011004 10.7189/jogh.07.011004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safon C., Buccini G.S., Eguiluz I.F., González de Cosio T. & Pérez‐Escamilla (2018). Can Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) impact breastfeeding protection, promotion and support in Mexico? A qualitative study. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sarkies, M. N. , Bowles, K.‐A. , Skinner, E. H. , Haas, R. , Lane, H. , & Haines, T. P. (2017). The effectiveness of research implementation strategies for promoting evidence‐informed policy and management decisions in healthcare: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 12, 132 10.1186/s13012-017-0662-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater, E. , Lasco, M. L. , Capelli, J. , & Pen, G. (2014). Health in action program, Brazil: A Program Impact Pathways (PIP) analysis. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35, S108–S116. 10.1177/15648265140353S203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R. C. , Cattaneo, A. , Bradley, E. , Chunharas, S. , Atun, R. , Abbas, K. M. , … Best, A. (2012). Rethinking health systems strengthening: Key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan, 27, iv54–iv61. 10.1093/heapol/czs090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Breastfeeding on the worldwide Agenda. (2013). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eapro/breastfeeding_on_worldwide_agenda.pdf

- UNICEF, WHO & Global Breastfeeding Collective . (2017). GLOBAL BREASTFEEDING SCORECARD. Tracking Progress for breastfeeding policies and programmes. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf?ua=1

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms. And Lifelong Effect. The Lancet, 387, 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Supporting information