Abstract

Previous studies have described barriers to access of childhood severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment, including long travel distances and high opportunity costs. To increase access in remote communities, the International Rescue Committee developed a simplified SAM treatment protocol and low‐literacy‐adapted tools for community‐based distributors (CBD, the community health worker cadre in South Sudan) to deliver treatment in the community.

A mixed‐methods pilot study was conducted to assess whether low‐literate CBDs can adhere to a simplified SAM treatment protocol and to examine the community acceptability of CBDs providing treatment. Fifty‐seven CBDs were randomly selected to receive training. CBD performance was assessed immediately after training, and 44 CBDs whose performance score met a predetermined standard were deployed to test the delivery of SAM treatment in their communities. CBDs were observed and scored on their performance on a biweekly basis through the study.

Immediately after training, 91% of the CBDs passed the predetermined 80% performance score cut‐off, and 49% of the CBDs had perfect scores. During the study, 141 case management observations by supervisory staff were conducted, resulting in a mean score of 89.9% (95% CI: 86.4%–96.0%). For each performance supervision completed, the final performance score of the CBD rose by 2.0% (95% CI: 0.3%–3.7%), but no other CBD characteristic was associated with the final performance score.

This study shows that low‐literate CBDs in South Sudan were able to follow a simplified treatment protocol for uncomplicated SAM with high accuracy using low‐literacy‐adapted tools, showing promise for increasing access to acute malnutrition treatment in remote communities.

Keywords: acute malnutrition, community based, community health worker, fragile states, severe acute malnutrition, South Sudan

Key messages.

Low‐literate CHWs in South Sudan were able to adhere to a simplified treatment protocol for uncomplicated SAM with high accuracy, using tools adapted for low literacy, developed using human‐centered design. These results show promise for bringing malnutrition treatment closer to remote communities.

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, about 52 million under‐five children (7.7% of all under‐five children) suffered from acute malnutrition in 2016, 17 million children of them from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) (UNICEF, World Bank, & WHO, 2017). In the world's youngest nation, South Sudan, nearly half of the population (5.3 million people) faced severe food insecurity and the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was less than $200 in 2017. One point one million children under five were estimated to be acutely malnourished at the end of 2017 (UNICEF, 2017).

Malnutrition is driven by factors such as widespread disease, poor health infrastructure, nonrecommended infant and young child feeding practices, inconsistent food availability and dietary diversity, and limited access to safe drinking water (Paul, Doocy, Tappis, & Funna Evelyn, 2014). Protracted conflict has cut off access to health services while increasing their demand. Community‐based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programming, which provides outpatient treatment for acutely malnourished children at static facilities, has improved access to care compared with previous inpatient nutrition programs. However, studies have shown that caregivers still experience barriers to accessing care, including long travel distances and high opportunity costs associated with frequent follow‐up visits required to the facility. (Guerrero, Myatt, & Collins, 2010).

Integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illness is a strategy that utilizes community health workers (CHW) to deliver treatment for uncomplicated cases of pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria in children under five. In most contexts, CHWs also screen children for SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) and refer children to health facilities for nutrition treatment if necessary. Studies have demonstrated that low‐literate CHWs can deliver timely and effective treatment for pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria if CHWs are effectively trained and supported, and protocols are appropriate to their capacity (Lainez et al., 2012). For example, a multicountry study has shown that the use of tools that do not require literacy or numeracy improves the classification of fast breathing by low‐literate CHWs (Noordam et al., 2015). Studies from Angola, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Mali have shown promising results with regard to how literate CHWs can effectively treat SAM (Alvarez Moran, Ale, Rogers, & Guerrero, 2017; Miller et al., 2014; Puett, Coates, Alderman, & Sadler, 2013). However, community‐based nutrition treatment models for low‐literate CHWs in crisis‐affected settings have not yet been studied (Friedman & Wolfheim, 2014).

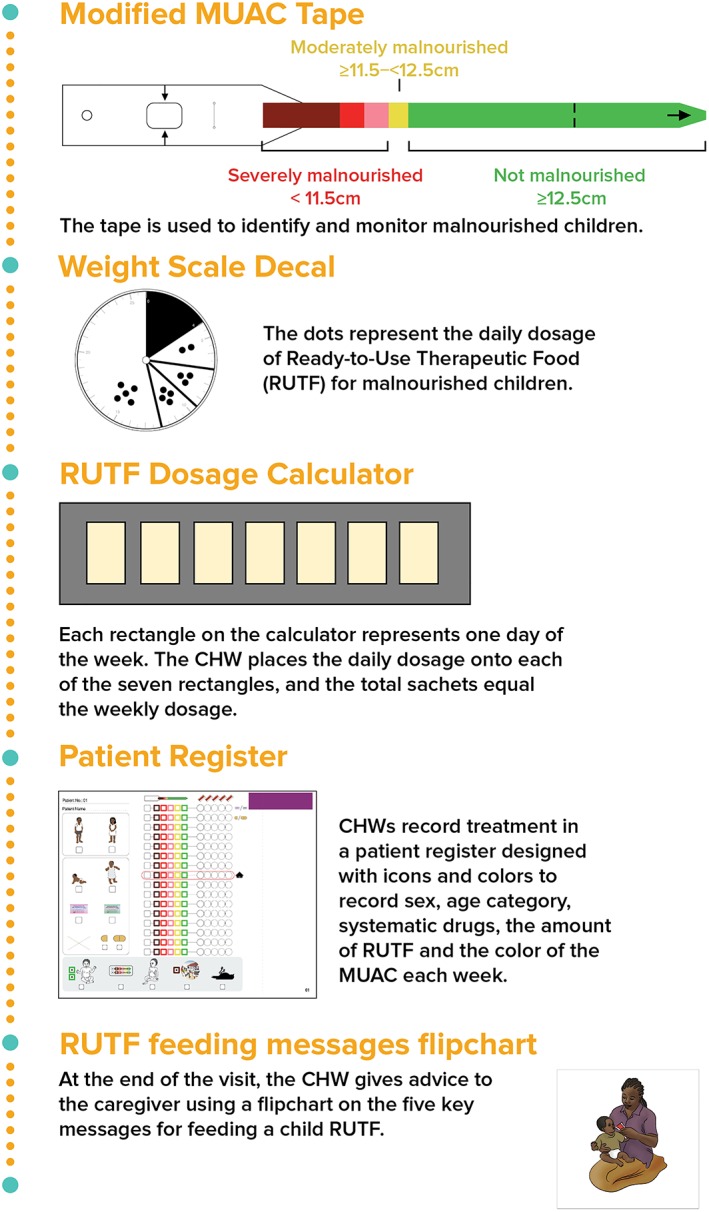

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) developed a simplified SAM treatment protocol and a set of low‐literacy‐adapted tools that could be used as a part of an iCCM program, taking a user‐centered approach in which CHW utility and feedback guided tool design. Several rounds of prototypes were field tested with CHWs in Mali, Chad, South Sudan, and India. The final set of tools does not require literacy or numeracy: (a) an adapted mid‐upper arm circumference (MUAC) tape with the standard green (≥12.5 cm) and yellow (≥11.5 cm and <12.5 cm) zones but further dividing the red MUAC zone in three (dark red <9.0 cm, red 9.0 < 10.25 cm, pink 10.25 < 11.5 cm) to better represent the gradation of malnutrition, (b) a weight scale decal to determine the daily ready‐to‐use therapeutic food (RUTF) dosage, (c) a dosage calculator to count the weekly RUTF dosage, (d) a patient register to track child treatment progress, and (e) a pictorial flipchart with key RUTF feeding messages. See Figure 1 for a brief description of the tools and Supplemental File 1 for a detailed description. Details on the design process are available elsewhere (Tesfai, Marron, Kim, & Makura, 2016).

Figure 1.

Tools adapted for low‐literate CHWs to treat acute malnutrition

This mixed methods, pilot study aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of low‐literate community‐based distributors (CBD, the CHW cadre in South Sudan) treating uncomplicated SAM cases in their community using the aforementioned tools and a simplified protocol. This manuscript focuses on the performance of the low‐literate CBDs in adhering to the treatment protocol. The child treatment outcomes and community acceptability of SAM treatment will be reported elsewhere.

2. METHODS

The study was conducted March–August 2017 in South Sudan's Aweil South County in Northern Bahr el Ghazal State, with a reported global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence of 17.7% in 2017, exceeding the emergency threshold of 15% (UNICEF, 2017). Only 41% of severely malnourished children were enrolled in CMAM treatment programs in Aweil South County in 2015 (IRC, 2015). Caregivers identified distance to health facilities, inaccessibility due to the rainy season and high opportunity costs as the primary barriers to access (IRC, 2015). The IRC was operating 10 static CMAM facilities as well as one stabilization center for treatment of SAM with medical complications in this area during the study period. The IRC also ran an iCCM program from 2014 to April 2017. The national iCCM guidelines give the CBDs the mandate to treat uncomplicated cases of pneumonia (antibiotics), diarrhoea (oral rehydration salt and zinc), and suspected malaria (Artemisinin‐based combination therapy). In addition, children who qualified as SAM (MUAC measurement <11.5 cm, red zone on the MUAC tape) or MAM (MUAC measurement between 11.5–12.5 cm, yellow zone on the MUAC tape) using the standard 3‐colour MUAC tape are referred to the nearest health facility. The iCCM program targets having one CBD per 40 households and that CBDs are located in communities beyond 5 km of a facility. Aweil South County consists of eight payams, or administrative units, with a collective catchment area of 13,223 households and approximately 600 CBDs operating in the area.

For this study, CBDs were trained on the use of the low‐literacy‐adapted tools and a simplified SAM treatment protocol. Subsequently, they were deployed to their communities where they passively screened to detect children suffering from uncomplicated SAM. Uncomplicated SAM in children ages 6–59 months was defined as MUAC between 9.0 and 11.5 cm (red or pink MUAC zones on the modified MUAC tape), without any danger signs, with a good appetite, and weight greater than 4 kg. MUAC less than 9.0 cm constituted a critical case and therefore referred. According to the South Sudan CMAM guidelines, any child weighing less than 4 kg is referred to the Stabilization Center. CBDs provided weekly SAM treatment for enrolled children in the CBDs' homes. CBDs screened children for any danger signs, took MUAC and weight measurements using adapted tools, determined the daily then weekly RUTF dosage to be provided, and recorded that week's MUAC colour zone and daily RUTF dosage on a patient register. During the first and the second visit, Amoxicillin and Albendazole were provided respectively. Children were treated until the child was discharged as recovered (two consecutive weeks in the green MUAC zone, defined as ≥12.5 cm), defaulted (two consecutive weeks absent), nonresponse (16 weeks of treatment without recovery), referred (if child developed medical complications), or died. The full description of the treatment protocol is available in Supplemental File 1.

2.1. Participant selection

On the basis of physical accessibility for the study team during the rainy season, only CBDs residing in four accessible payams of Aweil South County were selected for training. Out of the 397 CBDs working for the iCCM program in the four selected payams, the following CBDs were excluded (one CBD may contribute to multiple categories): two who were literate, one who was male, 171 who lived within 5 km of the nearest clinic, nine whose households are not accessible during the rainy season, 19 who participated in a previous iteration of field testing of the protocol and tools, and one who lived more than 60 min from the farthest household of their catchment area, leaving 106 CBDs. Fifteen CBDs from each payam were randomly selected for training participation (n = 60). Sociodemographic data were collected on all selected CBDs. Of them, 57 CBDs completed a 6‐day training, followed by a practical skills assessment. Only CBDs who scored at least 80% on the skills assessment were eligible for study participation. Forty‐four of the highest performing CBDs, 11 per payam, meeting the 80% cut‐off were deployed to treat children for SAM in their communities. The sample size of 44 was determined based on logistical capacity for study supervision. After 3 months of study implementation, a 1‐day refresher training was organized for all 44 CBDs.

2.2. CBD performance assessments

CBDs were trained on the following tasks: welcoming the caregiver, assessing for danger signs including bilateral pitting oedema, taking the child's MUAC measurement, conducting an appetite test, determining the weekly RUTF dosage based on the child's weight, administering medication (Amoxicillin for week 1, Albendazole for week 2), filling out the patient register, counselling the caregiver, child progress monitoring, and child discharge. A detailed description of the different tasks can be found on the checklist, Supplemental File 2. To assess CBD performance, a standardized performance checklist was developed based on the treatment steps CBDs were expected to take. This checklist was used after training for the skills assessment following the training, as well as during supervision through the study. Of the total 26 treatment steps, 11 were identified as critical actions on which errors could put the child in danger. The critical actions were taken from a previous study (Puett et al., 2013) and adapted to context. Research staff observed the CBDs using this checklist on a biweekly basis during supervision visits at the CBDs' homes and corrected the CBDs if a critical action was missed or performed incorrectly. At the end of the study, a random sample of 20 CBDs also received an endline skills assessment. The research staff pretested the performance checklist and participated in a standardization test prior to study start to ensure interrater and intrarater reliability. The research staff were also supervised regularly by a research manager to assure standardized use of the checklist.

2.3. Perceptions of CBD performance

Qualitative data were collected to assess stakeholder perceptions on low‐literate CBDs' ability to deliver malnutrition treatment. Twelve semistructured interviews (SSI) and nine focus group discussions (FGD) were held with CBDs, caregivers, community leaders, and IRC's nutrition program and research staff (see Table 1 for description). All data collection except interviews with the IRC staff was conducted by South Sudanese research officers in Dinka (local language in Aweil South County) and audio recorded. The IRC staff interviews were conducted in English by N. K. The research staff used a modified transcription and translation approach, given the challenges of identifying Dinka‐English translators. E. V. B., a non‐Dinka speaker, listened to the recordings of SSIs and FGDs alongside the South Sudanese research officer(s) who collected the data. The recording was orally translated into English several lines at a time by the research officer(s), which was then typed in English by E. V. B.

Table 1.

Participants in qualitative data collection

| Participants | Number of SSIs | Number of FGDs | Selection procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBDs | 4 | 4 |

SSIs: 2 lowest and 2 highest performers based on the most recent score available for each CBD. FGDs: Exclude CBDs who participated in SSIs. Random selection of 8 CBDs per health area. |

| Caregivers | 4 | 2 |

SSIs: 1 randomly selected caregiver out of each of the following four common treatment outcomes: cured, defaulted, nonresponse, and referred. FGDs: From 2 randomly selected health areas, 8 randomly selected caregivers. |

| CBD supervisors | ‐ | 2 |

2 randomly selected CBD supervisors from all four payams. All CBD supervisors that were responsible for RUTF stock management at restocking facilities. |

| Community leaders | 4 | ‐ |

Selection of one village per health area that had multiple CBDs providing SAM treatment in their communities. |

| IRC's nutrition program and research staff | 5 | 1 |

SSIs: IRC's nutrition program manager, research officers. FGDs: 2 randomly selected nutrition program staff members from each payam. |

2.4. Data analysis

Characteristics of CBDs and their performance scores were summarized. To identify factors that may affect performance, bivariate regression analyses were conducted with the final performance score as the dependent variable and CBD age, number of years working as a CBD, number of pregnancies, number of treatment sessions, and number of performance checklists completed as independent variables of interest. Multivariate regression analyses were not conducted due to the small sample size. Data were analysed using Stata version 13 (College Station TX: StataCorp LLC).

Qualitative data were analysed using Dedoose (Los Angeles, SocioCultural Research Consultants). A codebook was drafted based on the SSI and FGD guides. The first six transcripts were double coded by E. V. B. and N. K. to assure consistency in coding and addition of codes, and the remainder was coded by E. V. B. After all transcripts had been coded, reoccurring patterns and themes were identified and summarized.

2.5. Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the IRC's Institutional Review Board and the Ethical Committee of the Ministry of Health in Juba, South Sudan. Informed oral consent was obtained from all CBDs and caregivers and written consent from all other interviewees and focus group participants.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CBD characteristics

The characteristics of the 57 trained CBDs are described in Table 2, stratified by those selected to provide treatment and not selected. There were no statistically significant differences in characteristics between the CBDs who were selected for study participation and those who were not.

Table 2.

Community‐based distributor characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected for treatment (n = 44) | Not selected for treatment (n = 13) | ||

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 7 (15.9) | 1 (7.7) | 0.518 |

| 25–34 | 15 (34.1) | 2 (15.4) | |

| 35–44 | 9 (20.5) | 5 (38.5) | |

| 45–54 | 8 (18.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 55+ | 5 (11.4) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Ability to read | |||

| Yes | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0.583 |

| No | 43 (97.7) | 13 (100.0) | |

| Number of pregnancies | |||

| 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0.410 |

| 1–3 | 7 (15.9) | 0 | |

| 4–6 | 23 (52.3) | 9 (69.2) | |

| 7+ | 13 (29.6) | 4 (30.8) | |

| Religion | |||

| Christian | 31 (70.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.107 |

| Traditional | 13 (29.6) | 7 (53.9) | |

| Occupation | |||

| None | 2 (4.6) | 0 | 0.371 |

| Farmer | 38 (86.4) | 13 (100.0) | |

| Commerce | 4 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Number of years working as CBD | |||

| <1 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.828 |

| 1–2 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | |

| 3–4 | 25 (56.8) | 7 (53.9) | |

| 5–6 | 18 (40.9) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Estimated number of households in catchment area | |||

| Mean | 46.2 | 47.2 | 0.773 |

| Median | 44 | 45 | |

| IQR | 40–50.5 | 40–50 | |

| Range | 30–70 | 35–80 | |

3.2. Performance scores

Fifty‐seven CBDs completed the training as well as the skills assessment that followed. The CBDs scored a median of 98.9 (interquartile range [IQR] 86.3–100, range 67.5–100) on the performance checklist, with 52 (91%) CBDs scoring above the predetermined passing score of 80%. Forty‐nine percent of CBDs had perfect scores.

At the end of the enrollment period in May 2017, four of the 44 CBDs either had not treated any children or had discharged enrolled children prior to receiving the first supervision visit in their homes. Therefore, only 40 CBDs have data on their performance at the community level. CBDs treated a median of seven children (IQR 6–9, range 1–15). For our purposes, each weekly treatment for a single child is defined as “treatment session.” CBDs provided a median of 50 treatment sessions (IQR 35–64, range 14–111).

Table 3 presents the performance scores of the CBDs (n = 40) based on when the score was collected. A total of 141 supervisory visits were completed, with each supervisory visit resulting in a performance score. Between the post‐training skills assessment and the first supervision visit performance score, there was a drop from mean score of 97.4% to 82.3%. The time between the post‐training skills assessment and first supervision visit was a median 23 days (IQR 16–30 days, range 7–55 days). By the last supervision visit, the mean score increased back up to 93.9%. The time between post‐training skills assessment and last supervision visit was median 95 days (IQR 71–120 days, range 23–140 days).

Table 3.

CBD performance scores for treating SAM, stratified by number of supervision visits conducted

| Total number of supervision visits/performance checklists conducted | Immediately after training | Score during the first supervised treatment, at their home | Score during their last supervised treatment, at their home | Mean score across treatment period, at their home | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined | Mean | 97.4 | 82.3 | 93.9 | 89.9 |

| IQR | 97.5–100 | 71.4–98.6 | 87.1–100 | 86.4–96.0 | |

| Range | 80.0–100 | 12.9–100 | 61.4–100 | 59.0–100 | |

| % CBDs above 80% | N/A* | 67.5 | 90.0 | 87.5 | |

| 1–2 (n = 15 CBDs) | Mean | 96.8 | 87.0 | 88.2 | 87.6 |

| IQR | 96.3–100 | 77.1–98.6 | 81.4–100 | 78.6–98.6 | |

| Range | 93.8–100 | 61.4–100 | 61.4–100 | 61.4–100 | |

| % CBDs above 80% | N/A* | 73.3 | 80.0 | 73.3 | |

| 3–5 (n = 19 CBDs) | Mean | 97.2 | 77.4 | 97.3 | 90.1 |

| IQR | 97.5–100 | 70.0–85.7 | 98.6–100 | 87.1–95.2 | |

| Range | 80–100 | 12.9–100 | 70.0–100 | 59.0–100 | |

| % CBDs above 80% | N/A* | 68.4 | 94.7 | 94.7 | |

| 6–7 (n = 6 CBDs) | Mean | 99.4 | 85.7 | 97.4 | 95.0 |

| IQR | 98.8–100 | 71.4–100 | 100–100 | 93.8–95.9 | |

| Range | 97.5–100 | 71.4–100 | 84.3–100 | 91.9–100 | |

| % CBDs above 80% | N/A* | 50.0 | 100 | 100 |

Only CBDs with scores about 80% were included in the study.

The performance scores were also stratified by how many supervision visits were conducted per CBD. The number of supervision visits varied among CBDs depending on the total number of weeks the CBD had at least one child under treatment. The number of supervision visits received by each CBD was a median of 3.5 (IQR 2–5, range 1–7). For the 20 randomly selected CBDs who had a skills assessment conducted at the end of study implementation, their mean score was 94.3% (IQR 89.7–100, range 67.5–100), with 90% of CBDs achieving a score over 80%.

3.3. Task‐specific performance scores

The mean scores for each critical action assessed during treatment week 3–16 on the performance checklist can be found in Table 4. For over 90% of the observations, the CBDs correctly conducted the following actions: take MUAC measurement, conduct appetite test, provide the weekly RUTF dosage, and fill out the patient register. The lowest score was for conducting the bilateral pitting oedema check, with the action only taken in 78% (95% CI: 69.7–84.5) of the observations (Table 5).

Table 4.

Percent completion of each critical action (n = 40 CBDs, n = 141 performance checklists)

| Critical actions for follow‐up visits | % (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Correct patient register page identified on follow‐up visit | 88.7 (81.6–93.2) |

| Conducted oedema check | 78.0 (69.7–84.5) |

| Percentage of danger signs assessed (out of 10 danger signs) | 86.4 (81.8–90.9) |

| Correctly took MUAC measurement | 92.2 (85.3–96.0) |

| Correctly conducted appetite test | 95.7 (89.6–98.3) |

| Correct weekly dosage of RUTF given | 97.9 (93.6–99.3) |

| Correct filling of the patient register | 95.7 (89.4–98.3) |

Adjusted for clustering at the CBD level.

Table 5.

Bivariate regression results, examining the association between CBD characteristics and final performance score (n = 40)

| Variables examined | β (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| CBD age, in 10‐year increments (<25 as youngest category, to ≥45 as oldest category) | −1.5 (−6.4, 3.4) |

| Number of years working as a CBD (1–4 years as reference, vs. 5–6 years) | 2.0 (−4.6, 8.6) |

| Number of pregnancies | −0.8 (−2.3, 0.7) |

| Number of treatment sessions completed | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) |

| Number of performance checklists completed | 2.0 (0.3, 3.7) |

3.4. Predictors of performance scores

In the bivariate regression analyses, the number of performance checklists completed for a CBD had a statistically significant association with the last performance score recorded for the CBD. For each performance checklist completed, the final score of the CBD rose by absolute 2.0% (95% CI: 0.3%–3.7%). Considering the correlation between the number of performance checklists and the number of treatment sessions completed by the CBD (r = 0.7052), we ran a model controlling for the number of treatment sessions, and the association between performance checklists completed and the final recorded score remained significant (3.0%, 95% CI: 0.6%–5.4%).

3.4.1. Workload

Contrary to iCCM treatment of pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria, which was available from the CHWs on any day, SAM treatment was only provided on one fixed day per week. Creating a manageable workload, making it easier for CHWs and caregivers to remember on which day of the week they should make follow‐up visits, and facilitating the supply chain of RUTF were some of the factors that led to the decision to limit SAM treatment to a fixed day.

CBDs said that providing SAM treatment did not interfere with their other activities at home or income‐generating activities. Because CBDs only provided SAM treatment once a week in the early morning hours, they were able to resume their usual activities in the afternoon. One CBD indicated, “I do manage this work. Simply because the work of malnutrition treatment, it can't take you the whole day. So in the morning, I have to deal with the malnutrition treatment, then afterwards when I finish, I resume my normal work at home.” (SSI, CBD).

3.5. Perception of CBD performance

All CBDs repeatedly expressed how being able to take care of children with SAM in their community made them feel good and useful. One CBD indicated,

I feel proud when I have given treatment to a child and the child gets better. And then the community will appreciate you because you have done something good. If you came across a child and the child is not improving, then you can immediately refer the child and will get better treatment from there. That makes me feel good as well (SSI, CBD).

Some CBDs said that their relationship with their community had changed because they started providing SAM treatment “The way it has changed is … they call me a doctor. And if I meet someone on the road, that person will greet me: ‘how are you, doctor?’ … I respect them and they respect me” (SSI, CBD).

In general, caregivers expressed trust in CBDs and their ability or skills to provide SAM treatment. One caregiver said: “I only praise them [CBDs] for the good work that they have done, they should continue with it … They brought the treatment to the village and that is something good. So may God bless them” (SSI, caregiver). However, negative interactions between caregivers and CBDs were reported as well. Some community leaders and caregivers expressed that they suspected that CBDs were eating RUTF themselves or were providing preferential treatment for certain children. The most frequently mentioned example related to when the CBD determined that the child did not meet the eligibility criteria and therefore could not be admitted for SAM treatment. One caregiver expressed,

When I was visiting the CBD, other women came with their children who were not malnourished … The CBD told them that their children were not sick and that they had to go back home and continue to give food to their child. Then [the other caregivers] got annoyed and went back to their houses feeling unhappy … And then they began to complain saying that ‘you are friends with the CBD, that is why your child is admitted. And that is why the CBD did not treat my child (FGD, caregiver).

Some CBDs described difficulties in completing a treatment session in relation to their own children. One CBD reported a need to send her own children away from her compound although she provided treatment to children in her community to avoid conflict. She noted,

My child would become crazy when it's time for me to give treatment … My little boy was terrible at my house, and I was told during the training that we shouldn't be giving PlumpyNut to our kids. So when it's [time to provide] treatment, I ask my other children to take the boy away from me, and then later on I'd start the work without the boy (IDI, CBD).

3.6. Feedback on training and supervision

CBDs expressed their appreciation for the 6‐day training and the subsequent skills assessment. One CBD indicated, “The training was good because some things were difficult for us but now we understand. Also, the training made us to be a group like this. Because of the training we are able to know one another and if we meet on the road we are able to greet each other with names” (FGD, CBD). Research officers explained that the use of songs, practical exercises, and role plays were effective strategies during the training of low‐literate CBDs. All CBDs said that the biweekly supervision visits were helpful and allowed them to correct any mistakes, which was confirmed by research officers and CBD supervisors. One CBD said, “Supervision was good for me because when the research officer came we worked together. He corrected my mistakes and showed me the correct way to do it. And it helped me a lot” (SSI, CBD).

4. DISCUSSION

In accordance with previous study results of literate CHWs, (Puett et al., 2013) this study demonstrated that low‐literate CBDs in South Sudan were able to follow a simplified treatment protocol for uncomplicated SAM with high accuracy, using adapted tools. Forty CBDs with 141 performance checklists completed achieved a mean score of 89.9% across the study implementation period. This study was the first to focus on low literacy and acute malnutrition treatment, and adds to the existing literature that have previously shown that literate CHWs are able to provide malnutrition treatment in their communities. The high CBD performance scores demonstrate that low‐literate CBDs are able to accurately provide SAM treatment in their communities. This, accompanied by positive results of treatment outcomes of the treated children, which will be presented in a later publication, shows promise for bringing SAM treatment closer to the homes of caregivers, thereby decreasing travel distance and time to static facilities.

The standard CMAM guidelines treat uncomplicated SAM cases under two different protocols: (a) protocol for a child to recover from SAM to MAM and (b) once reaching MAM, another protocol for a child to recover from MAM to full recovery. The intervention design of our study eliminates that distinction and treats SAM children under one protocol to full recovery. Previous literature suggests that using the discharge criteria of greater than or equal to 12.5 cm (the full recovery criterion) for SAM children show lower relapse and mortality rates, (Binns et al., 2016; Somasse, Dramaix, Bahwere, & Donnen, 2016) so scale‐up of this model that treats SAM children under one streamlined protocol to full recovery could contribute to a better sustained reduction in prevalence of GAM. Furthermore, the ability to stem the infection‐malnutrition cycle by integrating iCCM and malnutrition treatments is likely to contribute further to this reduction.

This study observed absolute 2.0% increase in performance score for each additional supervision visit. This supports a previous study of literate CHWs, which suggests that the level of accuracy depends on being closely supervised (Alvarez Moran et al., 2017). This suggests the importance of frequent supportive supervision visits during which treatment is observed, and any errors are corrected. Because of the relatively small sample size of this study, multivariate analyses were not conducted. Furthermore, although research officers were able to conduct biweekly supervision visits, it remains to be further explored how to manage supervision when the program is implemented at scale. We saw a low performance score on checking for bilateral pitting oedema, but we hypothesize that this is due to CBDs visually recognizing an obvious lack of swelling in the feet and thus forgoing the check.

Various adaptations and innovations in tools have been introduced to previous CHW programs to improve performance. We have shown in a separate operational research study that proper adaptation of iCCM protocols and tools to CHW literacy levels and cultural context can positively impact the quality of service and the length of time taken to deliver the service (IRC, 2017). A group of NGOs have also tested colour‐coded counting beads for CHWs to classify a child as having suspected pneumonia and showed improvements in classification (Noordam et al., 2015). The existing literature and the results of this study highlight the potential of CHWs, literate or otherwise, that may currently not be properly engaged due to poor recognition by NGOs or Ministries of Health of the need to make appropriate program adaptations based on human resource.

Qualitative data showed that communities in general appreciated the program and the proximate availability of SAM treatment. Despite community sensitization meetings that were held at the beginning of study implementation, CBDs also experienced tension. At the time of study implementation, Aweil South County experienced severe food insecurity, which may have impacted demand for RUTF and increased tension between community and CBDs. Some community leaders and caregivers expressed that they suspected that CBDs were eating RUTF themselves or provided preferential treatment for certain children. This was not directly observed by research officers. For future programming, community dialogue should be more extensive and should be more frequently conducted.

The user‐centred approach that was used to develop the simplified tools emphasized CHW contributions, thus better assuring prior to study implementation the capacity among low‐literate cadres to use the tools. However, sufficient resources had to be made available to support the multiple rounds of piloting and adaptation of the simplified tools. The design phase, prior to the start of the formal research described here, lasted approximately 2 years, starting from scratch and including five rounds of in‐country workshopping and field testing with CHWs, of which three rounds involved multiple countries. Tools were tested in South Sudan three times prior to study implementation. Despite this high resource input, we anticipate that the benefit of usable job aids and tools will result in better cost efficiency. In a previous operational research study conducted by the IRC, we observed that low‐literacy adapted job aid and tools for an iCCM program led to better adherence to treatment protocol, better time efficiency per visit, and better cost‐efficiency (IRC, 2017). It is important to note here that we still face the practical challenge of local production of the tools. In the design phase, we strived to locally produce the simplified tools, however some of the simplified tools required production in Kenya or the U.S. Tools that could be produced in‐country reduced costs but at the sacrifice of quality. When scaling up this approach, careful considerations will need to be made in relation to the balance of cost and quality.

The acute malnutrition treatment simplified tools working group, led by the IRC, is a coalition of implementing NGOs who are invested in developing tools for low‐literate CHWs to treat acute malnutrition in difficult‐to‐reach contexts. As a follow‐on to this study, Malaria Consortium, Concern Worldwide, Save the Children, and Action Against Hunger are all conducting similar pilots in four different contexts across three different countries (Nigeria, Malawi, and Kenya) to test the adaptability of the tools and to evaluate the performance of the CHWs and outcomes of the treated SAM children in their respective contexts. By having evidence across multiple contexts, we intend to reflect on the generalizability of this low‐literate CHW treatment delivery mechanism and assess what barriers and challenges may exist in disseminating the tools and implementing the delivery system in different contexts, including key questions such as supply chain management. We then intend to test the scalability of the treatment delivery model and the integration into the iCCM service delivery mechanism, using the finalized set of low‐literacy‐adapted tools and lessons learned from the respective pilot projects. We will also need to advocate to Ministries of Health that such adaptations will benefit CHW cadres; even in some contexts where literacy is a defined criterion to serve as a CHW, capacity gaps are often seen.

There were several limitations to the study. A concern with adding additional components to iCCM is potentially overburdening CHWs (Bhattacharrya, Winch, & Leban, 2001). Although there is some evidence that adding SAM management to a CHW's workload does not necessarily result in decreased quality of care, provided the CHWs receive adequate training and supervision (Puett, Coates, Alderman, Sadruddin, & Sadler, 2012). We were unable to evaluate the impact of workload on the quality of care and CBD performance. Another NGO took the implementation of the iCCM program over from the IRC in our study area in April 2017, and the subsequent NGO did not begin operations of the iCCM program for the remainder of the study period. Therefore, questions around the integration of iCCM and SAM treatment, including the added workload of CHWs, remain for future research.

The critical actions for performance assessment were identified as actions that could have potential consequences for the child's health if incorrectly executed. The critical actions were initially derived from a previous study (Puett et al., 2013) and adapted to context. However, determination of what is “critical” is subjective, and others may weigh and score the actions differently. Only CBDs that score 80% or higher on the critical actions of the performance assessment checklist directly following the training. A previous study that assessed performance of literate CHWs utilized a predetermined cut‐off of 90% of error‐free case management (Puett et al., 2013). Considering that we were working with low‐literate CBDs, we decided to lower the cut‐off to 80%, recognizing that the determination of the cut‐off is also subjective.

We were not able to recruit independent qualitative data collectors due to a lack of local qualitative health research expertise. Therefore, male research officers who were also responsible for the supervision of the CBDs conducted the SSIs and FGDs, which may have led to some reactivity in interviewee responses. As the interviewers had closely collaborated with the female CBDs during study implementation, we do not expect that there was a lack of rapport. However, interviewers were less familiar with the female caregivers who participated in the interviews and focus groups, and the gender balance, as well as perceived hierarchy, may have affected their responses. Finally, the transcripts that were developed were not word‐for‐word transcriptions, thus we expect that some content and nuance may have been lost.

5. CONCLUSION

This study shows that low‐literate CBDs in South Sudan were able to follow a simplified treatment protocol for uncomplicated SAM with high accuracy, using adapted tools. These results show great promise for bringing malnutrition treatment closer to remote communities. There are a number of questions that remain for future exploration, including implications on performance if the intervention was scaled up, CHW workload and performance with integration of SAM treatment into the iCCM algorithm and supervision if the number of CHWs providing SAM treatment increased.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

EVB, AZ, and NK designed the study, supported the implementation and data collection. EVB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, analysed the qualitative data, and managed the study. NK analysed the quantitative data and made significant contributions to the manuscript. CT led the tool and protocol development and contributed to the conception of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supporting information

Data S1. Documentation of treatment protocol

Data S2. Performance supervision checklist

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the research officers for this study: Barnabas Mbele John, John Dot, Luka Deng Atak, and Santino Anyuon Arop. We thank the IRC South Sudan staff (Emmanuel Ojwang, Stanley Anyigu, Mena Fundi Eso Adalbert, and others), South Sudan Nutrition Cluster, and South Sudan Ministry of Health for their support.

Van Boetzelaer E, Zhou A, Tesfai C, Kozuki N. Performance of low‐literate community health workers treating severe acute malnutrition in South Sudan. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(S1):e12716 10.1111/mcn.12716

REFERENCES

- Alvarez Moran, J. L. , Ale, F. G. , Rogers, E. , & Guerrero, S. (2017). Quality of care for treatment of uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition delivered by community health workers in a rural area of Mali. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14 10.1111/mcn.12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharrya, K. , Winch, P. , & Leban, K. (2001). Community health worker incentives and disincentives: How they affect motivation, retention and sustainability. Retrieved from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACQ722.pdf.

- Binns, P. J. , Dale, N. M. , Banda, T. , Banda, C. , Shaba, B. , & Myatt, M. (2016). Safety and practicability of using mid‐upper arm circumference as a discharge criterion in community based management of severe acute malnutrition in children aged 6 to 59 months programmes. Arch Public Health, 74, 24 10.1186/s13690-016-0136-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L. , & Wolfheim, C. (2014). Linking nutrition and (integrated) community case management (iCCM/CCM): A review of operational experiences.

- Guerrero, S. , Myatt, M. , & Collins, S. (2010). Determinants of coverage in community‐based therapeutic care programmes: Towards a joint quantitative and qualitative analysis. Disasters, 34(2), 571–585. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Rescue Committee . (2015). Coverage assessment: Semi‐quantitative evaluation of Access & Coverage—Aweil South County, Republic of South Sudan. Retrieved from https://www.coverage-monitoring.org

- International Rescue Committee (2017). Faster, Better, Lower Cost: Using simplified pictorial tools and a modified training curriculum to improve the quality and reduce the cost of iCCM in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/1546/raceresearchbriefdrc20174-6-17.pdf

- Lainez, Y. B. , Wittcoff, A. , Mohamud, A. I. , Amendola, P. , Perry, H. B. , & D'Harcourt, E. (2012). Insights from community case management data in six sub‐Saharan African countries. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 87(5 Suppl), 144–150. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N. P. , Amouzou, A. , Tafesse, M. , Hazel, E. , Legesse, H. , Degefie, T. , … Bryce, J. (2014). Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: Implementation strength and quality of care. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 91(2), 424–434. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordam, A. C. , Barbera Lainez, Y. , Sadruddin, S. , van Heck, P. M. , Chono, A. O. , Acaye, G. L. , … Kallander, K. (2015). The use of counting beads to improve the classification of fast breathing in low‐resource settings: A multi‐country review. Health Policy and Planning, 30(6), 696–704. 10.1093/heapol/czu047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A. , Doocy, S. , Tappis, H. , & Funna Evelyn, S. (2014). Preventing malnutrition in post‐conflict, food insecure settings: A case study from South Sudan. PLoS Currents, 6 10.1371/currents.dis.54cd85fa3813b0471abc3ebef1038806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puett, C. , Coates, J. , Alderman, H. , & Sadler, K. (2013). Quality of care for severe acute malnutrition delivered by community health workers in southern Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(1), 130–142. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puett, C. , Coates, J. , Alderman, H. , Sadruddin, S. , & Sadler, K. (2012). Does greater workload lead to reduced quality of preventive and curative care among community health workers in Bangladesh? Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 33(4), 273–287. 10.1177/156482651203300408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasse, Y. E. , Dramaix, M. , Bahwere, P. , & Donnen, P. (2016). Relapses from acute malnutrition and related factors in a community‐based management programme in Burkina Faso. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(4), 908–917. 10.1111/mcn.12197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfai, C. , Marron, B. , Kim, A. , & Makura, I. (2016). Enabling low‐literacy community health workers to treat uncomplicated SAM as part of community case management: Innovation and field tests. Retrieved from https://www.ennonline.net/fex/52/communityhealthworkerssam

- UNICEF . (2017). South Sudan situation report: 30 September 2017. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF%20South%20Sudan%20Humanitarian%20SitRep%20%23113%20_%2030%20September%202017.pdf

- UNICEF, World Bank, & WHO . (2017). Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates 2017. Retrieved from http://datatopics.worldbank.org/child-malnutrition/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Documentation of treatment protocol

Data S2. Performance supervision checklist