Abstract

Despite efforts to support breastfeeding for HIV‐positive mothers in South Africa, being HIV‐positive remains a barrier to initiating and sustaining breastfeeding. The aim was to explore decision‐making about infant feeding practices among HIV‐positive mothers in a rural and urban settings in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. HIV‐positive pregnant women were purposively sampled from one antenatal clinic in each setting. A qualitative longitudinal cohort design was employed, with monthly in‐depth interviews conducted over 6 months postdelivery. Data were analysed using framework analysis. We report findings from 11 HIV‐positive women within a larger cohort. Participants were aged between 15 and 41 years and were all on antiretroviral therapy. Before delivery, nine mothers intended to exclusively breastfeed (EBF) for 6 months, and two intended to exclusively formula feed (EFF). Three mothers successfully EBF for 6 months, whereas four had stopped breastfeeding, and two were mixed breastfeeding by 6 months. Mothers reported receiving strong advice from health workers (HWs) to EBF and made decisions based primarily on HWs advice, resisting contrary pressure from family or friends. The main motivation for EBF was to protect the child from HIV acquisition, but sometimes fear of mixed feeding led to mothers stopping breastfeeding entirely. Infant feeding messages from HWs advice were frequently inadequate and out of date, and failed to address mothers' challenges. Minimal support was provided for EFF. In conclusion, HWs play a pivotal role in providing infant feeding support to HIV infected mothers, but need regular updates to ensure if advice is correct and appropriate.

Keywords: breast feeding, health workers, HIV infection, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission, South Africa

Key messages.

HIV‐infected women are strongly motivated to comply with infant feeding counselling messages from HWs, and resist contrary messages from friends and family, to prevent their infants acquiring HIV infection.

Infant feeding counselling messages given to HIV‐infected mothers by HWs are often outdated, confused and prescriptive, and fail to provide individual support, leading to inappropriate infant feeding decisions.

In addition to skills development for facility‐based HWs, alternative approaches to providing accessible, community‐based infant feeding counselling and support for HIV infected breastfeeding women should include training and deployment of peer counsellors, community health workers, and use of support groups.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding is the gold standard for infant feeding with proven lifelong benefits for both mothers and children (Rollins et al., 2016). Breastfed infants have lower mortality and morbidity from infectious diseases and malnutrition. Long‐term benefits include reductions in obesity and Type 2 diabetes among children, and reduced incidence of breast/ovarian cancer among mothers (Chowdhury et al., 2015). Although universal adoption of optimal breastfeeding practices could reduce global child deaths by more than 800,000, rates of exclusive and sustained breastfeeding are low in most countries globally (Victora et al., 2016). Improving rates of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) to 50% for the first 6 months of life has been adopted as a key target for the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition (United Nations Decade of Nutrition 2016‐2025, 2016).

Globally, 1.4 million babies were born to HIV‐positive women in 2015, most in Sub‐Saharan Africa (UNICEF, 2016). Since the start of the HIV epidemic, the risk of postnatal HIV transmission through breastfeeding has led to a series of infant feeding recommendations for HIV‐exposed infants, many of which were not supportive of breastfeeding (World Health Organisation, 2001; World Health Organisation, 2006; World Health Organisation, 2010). These recommendations have been controversial with policymakers having to weigh the child survival benefits of breastfeeding and the dangers of formula feeding, against the risk of breastfeeding HIV transmission (Chinkonde, Sundby, de Paoli, & Thorsen, 2010). However, in recent years, antiretroviral treatment (ART) has become increasingly effective and accessible, and current WHO PMTCT guidelines recommend lifelong ART for all pregnant women from the time of HIV diagnosis (World Health Organisation, 2012). This is known as option B plus and is standard practise in most high HIV prevalence African countries (Gumede‐Moyo, Filteau, Munthali, Todd, & Musonda, 2017). Recent research demonstrates the risk of HIV transmission from mother‐to‐child for breastfed infants is low when the mother is on long‐term ART, regardless of mixed feeding (Gumede‐Moyo et al., 2017). Therefore, in 2016 feeding, recommendations for HIV‐exposed infants were aligned with the recommendations for all children; EBF for 6 months followed by ongoing breastfeeding for 2 years (World Health Organisation & United Nations Childrens Fund, 2016), as long as the mother is adherent to ART and virally suppressed (Chikhungu, Bispo, Rollins, Siegfried, & Newell, 2016). However, in many African settings, poor adherence and loss to follow up has been a major concern (Rachlis et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2014).

As a result of frequent policy changes, HWs have received a variety of changing and often conflicting messages, which have caused confusion among HWs providing infant feeding advice (Moland et al., 2010a; Paoli, Mkwanazi, Richter, & Rollins, 2008). Mixed breastfeeding (giving the infant breastmilk as well as other food or fluids) was strongly discouraged as the worst possible feeding practice during the first 6 months of life, leading to higher rates of HIV breastfeeding transmission (Coovadia et al., 2007; Doherty, Sanders, Goga, & Jackson, 2011). As a result, HIV‐infected mothers face difficult choices about feeding their babies, and HIV‐positive status remains a barrier to initiating and sustaining breastfeeding (Zulliger, Abrams, & Myer, 2013).

In South Africa (SA), HIV prevalence is high, and is highest in KwaZulu‐Natal (KZN) province, where 40.1% of women attending government antenatal clinics (ANC) were found to be HIV‐infected in 2013 (South Africa National Department of Health, 2013b). At the time of this study, infant feeding guidelines for HIV‐exposed infants recommended 6 months EBF followed by addition of nutritious complementary feeds and continuation of breastfeeding until 12 months, as long as there is viral suppression (South Africa National Department of Health, 2014. However, high rates of loss to follow‐up among mothers have been documented in the postnatal period (Fox et al., 2014; Chetty et al., 2012), suggesting adherence support needs strengthening. Despite this, feeding recommendations in South Africa have since been aligned with 2016 WHO guidelines, which recommend continued breastfeeding to 2 years (World Health Organisation, 2016; Department of Health, 2017).

HWs have been shown to be key role players in conveying infant feeding messages to HIV‐positive mothers (Fjeld et al., 2008). However, knowledge and attitudes of HWs have at times been out of step with current guidelines (van Rensburg, Nel, & Walsh, 2016; Piwoz et al., 2006), and the manner in which HWs communicate infant feeding messages has been inadequate (Chinkonde, Sundby, & Martinson, 2009; Doherty et al., 2007). Another challenge for HIV‐positive women has been the social circumstances in which they make decisions, leading to departure from their original feeding choice (Chaponda, Goon, & Hoque, 2017; Jama et al.,2017). It is important to determine whether infant feeding practices among HIV‐infected mothers reflect current recommendations and, if not, to understand how mothers make infant feeding decisions. This paper presents results from a study to explore infant feeding practices among HIV‐positive women and identify key role players influencing their infant feeding decisions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This study adopted a longitudinal qualitative design to prospectively capture critical moments and processes involved in infant feeding choices made by HIV‐infected women over the period from birth to 6 months. This methodology was chosen as the most appropriate method to explore the lived experience of change and capturing transitions (Calman, Brunton, & Molassiotis, 2013).

2.2. Study site

The study was conducted in one urban and one rural setting in KZN, South Africa. The rural site was a district in northern KZN with a population of 120,000, with high rates of illiteracy, poverty, and malnutrition, where 44.1% of pregnant women were HIV‐infected in 2013 (South Africa National Department of Health, 2013a). The population is mainly African, most of whom speak isiZulu and live in scattered households, often informally built, with poor access to basic services like water, sanitation, and electricity (KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health, 2015a). The urban site was an industrial area, with about 290,000 residents and characterised by high unemployment. The population is culturally mixed with the majority being African, but with a substantial minority of Indian origin, who largely live in formal housing with good access to water, sanitation, and electricity. However, informal structures do exist in this urban area where infrastructure and basic services are lacking (KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health, 2015b). The area is also severely affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with 41.1% antenatal HIV prevalence (South African National Department of Health, 2013a). Thus, both study sites were situated in districts with a high HIV burden.

2.3. Sampling and recruitment

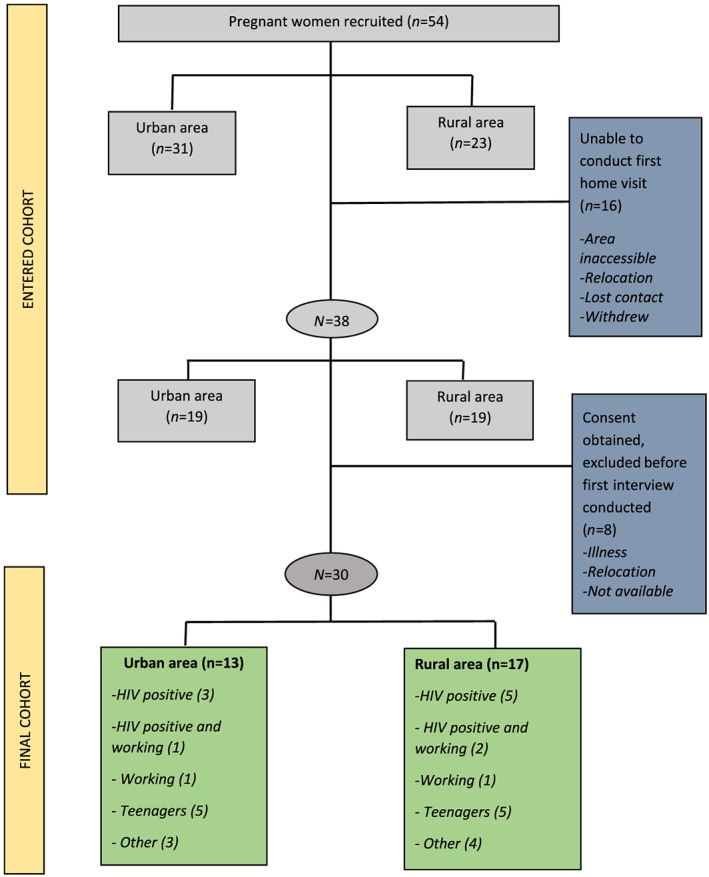

We report findings from HIV‐positive women who formed a part of a larger qualitative cohort study (Jama et al., 2017; Jama et al., 2018). Pregnant women were eligible to participate if they were aged 15 years or older, planned to give birth in the local hospital and reside in the area with the baby for 6 months postdelivery. A purposive sampling technique was used to ensure inclusion of women who reported themselves HIV‐positive, as well as working women and teenagers (aged 15–19 years), to ensure representation of groups with differing feeding practices (Mnyani et al., 2016; Smith, Coley, Labbok, Cupito, & Nwokah, 2012; Mandal, Roe, & Fein, 2010). Figure 1 shows the recruitment process and cohort profile, with some overlap between categories because some HIV‐positive women were also working women or teenagers.

Figure 1.

Participant sampling and cohort profile

Pregnant women (>36 weeks pregnant) were approached by fieldworkers at one antenatal clinic at each site. Women were given an explanation of the study, and those who expressed willingness to participate provided contact details, and a home visit was arranged. Eleven HIV‐positive women were recruited. All participants were isiZulu speakers.

2.4. Data collection

An in‐depth interview guide was developed to explore three main topics, current feeding practices, reasons for adopting particular feeding practices, and people involved in making infant feeding decisions.

Field workers underwent extensive training in in‐depth interview skills over 2 weeks, including role‐plays and practice interviews with mothers until their interviews skills were adequate. Two fieldworkers, one deployed in each site, undertook seven household visits to each participant. The first visit was conducted before delivery to complete recruitment, obtain consent, and collect demographic data and data about intended feeding practices. After delivery, women were interviewed every month for 6 months, starting within 2 weeks of the baby's birth. Interviews were conducted in the participant's home, in their home language, and were audio recorded. Each interview included a review of previous interviews, to encourage focus on longitudinal elements of infant feeding practices and decision‐making (Calman et al., 2013), and this also served to validate the data from the previous interviews. Audiotapes of interviews were reviewed regularly during data collection by experienced qualitative researchers to ensure high quality interview data and, when required, field workers were given feedback to improve interview quality. Reviews of the audiotapes were initially conducted frequently (approximately weekly), but the frequency was reduced as the quality of interviews improved. The primary concern from the audiotape reviews was that the FWs were less able than more experienced researchers to apply their judgement in following up probes, so they tended to stay with the script, sometimes missing important discussion points. If a probe was missed, this would be highlighted on review of the audiotape, and FWs would make sure the topic was further explored at the next interview.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee at the University of KwaZulu‐Natal (BE301/15) and the KZN Department of Health. Anonymised audio recordings and transcripts were stored at University of KZN in a password‐protected file.

2.6. Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated into English. Framework analysis was used for analysis in order to provide coherence and structure while answering clear predefined questions in a relatively short time period (Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, 2013). This method is not linked to a single theoretical approach but can be modified to fit several qualitative approaches aiming to generate themes. Framework analysis was selected as a suitable approach to manage and organise the data and provide a systematic analysis structure for this large dataset. Although we used a priori themes from the interview guide during analysis, we also allowed for inductive themes to emerge from the data, using this method to systematically reduce the data while still retaining its complexity and thick description (Ritchie & Spencer, 2002).

Transcripts were exported to NVivo v10. Guided by five stages of framework analysis (familiarization, developing analysis framework, coding, charting, mapping and interpretation), two experienced qualitative researchers read the transcripts and developed an analysis framework using a priori themes from interview questions, as well as themes that emerged from the data. Data were coded and grouped to highlight longitudinal aspects of participants' responses as well as linear aspects of data across participants. To ensure intercoder reliability, the two researchers coded a subset of transcripts independently and discussed the emerging key concepts until agreement was reached. Comparative analysis was used to check consistency and limit bias, and researchers continued analysis using a consensus approach until no further themes were identified. Findings were then discussed with the research team to ensure accurate interpretation of the data.

3. RESULTS

A total of 61 in‐depth interviews were conducted with 11 HIV‐positive mothers between November 2015 and October 2016. Ten mothers completed the six‐month follow‐up period: Eight mothers were interviewed six times, and two interviewed five times. One mother dropped out after three interviews.

Nine HIV‐positive participants expressed they planned to exclusively breastfeed (EBF), and two intended to exclusively formula feed (EFF). Demographic details and feeding practices of participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Feeding intentions, practices, and rationale

| Participant's details | Sociodemographics | Health care | Intended feeding method | Antenatal feeding intention and rationale | Age when other liquids or solids introduced | Rationale for maintenance of EBF/change in feeding practice | Ongoing feeding prractice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural 02: | |||||||

|

Age: 36 years Education level completed: grade 12 Still at school: no Employed: no |

Main source of drinking water: river water/dam/lake/pond Toilet type: pit latrine Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: four Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Currently taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: not recorded |

EBF | “I chose to breastfeed him because there is a bond between me and him. He can see that I am his mother and it is healthy, it protects him against diseases” | 2 months | “I give him gripe water once a day as it cleans his stomach and help with his bowel movement” | Breastfeeding continued to 6 months, gripe water was the only other fluid given during that period. Mother plans to continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months |

| Rural 04: | |||||||

|

Age: 34 years Education level completed: grade 11 Still at school: no Employed: no |

Main source of drinking water: river water/dam/lake/pond Toilet type: ventilated pit latrine Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: six Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no HIV CARE Currently taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EBF | “I think … I didn't have much knowledge because when I found out that I must breastfeed exclusively and not give the baby other food, I thought they are saying that because I'm positive until the nurses explained to me that, ‘no, everyone must breastfeed exclusively for 6 months’ whether positive or negative and then I made a decision to breastfeed exclusively” | 6 months | “I think I won't be able to afford formula milk because it's expensive, he will continue with breast milk until he's 12 months. Also, I wouldn't know whether he will be infected from mixed feeding and I told myself that it better to feed him breast milk only” | Breastfeeding continued, mother plans to continue beyond 6 months |

| Rural 08: | |||||||

|

Age: 26 years Education level completed: grade 1 Still at school: no but intends to return Employed: no

No longer in a relationship with the child's father |

Main source of drinking water: public tap Toilet type: bush/veld/no toilet Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: five Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: yes Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: NOT disclosed to significant others |

EBF | “At the clinic they said the baby must breastfeed for 6 months before you mixed feed” | 4 months | “I was not happy with his body weight. The neighbours also commented that if he doesn't eat he will get sick, from there on I regretted giving breastmilk only and just gave the baby real food” | Mixed fed for a month and breastfeeding stopped abruptly at 5 months because of pressure from family and neighbours |

| Rural 09: | |||||||

|

Age: 21 years Education level completed: grade 10 Still at school: no but intend to return to complete her education Employed: no |

Main source of drinking water: piped water in another yard Toilet type: ventilated pit latrine Household connected to electricity: yes |

Number of ANC visits: four Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: yes Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: NOT disclosed to significant others |

EBF | “The sisters (nurses) from the hospital, they told us that how important it is to breastfeed and I thought it better to breastfeed him for these 6 months and stop and give other foods” | 4 months | “He was not getting full and my milk was not coming out well” | Breastfeeding stopped abruptly at 4 months due to perceived insufficient milk |

| Rural 11: | |||||||

|

Age: 38 years Education level completed: grade 4 Still at school: no Employed: no |

Main source of drinking water: piped water in the yard Toilet type: ventilated pit latrine Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: five Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EBF | “I wanted to FF, but changed my mind when they (nurses) told me that even though I have this problem (HIV) I can breastfeed then I change my mind to exclusive breastfeeding” | 6 months | “He gets healthy; he is protected from diseases. Breast milk is healthy” | Intentions to continue breastfeeding not stated |

| Rural 18: | |||||||

|

Age: 28 years Education level completed: grade 11 Still at school: no Employed: yes |

Main source of drinking water: piped water in the yard Toilet type: ventilated pit latrine Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: eight Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: yes Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: not recorded |

EFF | “My problem is that I don't trust myself because I'm HIV positive so now I don't like the baby to suck my breasts. Sometimes the breasts do develop sores and that means the baby will go hungry just because you have a sore in your breast. The baby sometimes develop thrush in his tongue, when you clean this thrush he can get hurt and then you breastfeed him with wounded breast then the baby become infected yet he was born negative so you must keep him negative and think about his future” | 3 days | Gave breastmilk for 3 days while in hospital. Mother reported this was because there was no formula milk available at the hospital. Changed to exclusive formula feeding after arriving home | |

| Rural 24: | |||||||

|

Age: 34 years Education level completed: grade 11 Still at school: no Employed: yes |

Main source of drinking water: river/dam/lake Toilet type: ventilated pit latrine Household connected to electricity: no |

Number of ANC visits: one Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Currently taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: not recorded |

EBF | “It is because, sister, I'm not working, it (breastmilk) would have helped him to grow well and not get hungry because he would always get milk from my breasts. But because he was not getting full I couldn't deprive him of what he wants so I bought (formula milk)” | 1 week | “He cried when I breastfed him. I bought formula milk because I thought he's hungry, my breast are not producing enough milk” | Breastfeeding stopped after 1 week due to perceived insufficient milk |

| Urban 03: | |||||||

|

Age: 34 years Education level completed: grade 12 Still at school: no Employed: yes |

Main source of drinking water: piped inside the house Toilet type: flush toilet inside the house Household connected to electricity: yes |

Number of ANC visits: six Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EBF | “I breastfed my older children before but I breastfed without any knowledge so when they told me that I can still breastfeed, I chose to exclusively breastfeed” | 3 months | “I have decided to go back to work on the 1st and I am scared that the nanny/aunt will give her water, medicine which is wrong when I am away, so I decided to change her to formula” | Breastfeeding stopped abruptly at 3 months because she returned to work |

| Urban 07: | |||||||

|

Age: 41 years Education level completed: grade 11 School: no Employed: no Relationship status: still in a relationship with the father |

Main source of drinking water: piped inside the house Toilet type: flush toilet inside the house Household connected to electricity: yes |

Number of ANC visits: six Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Currently taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EBF | “I want to prove what the nurses said, that I can have a baby who is negative while I am positive” | 6 months | “What keeps me going is that I like that he doesn't get sick, he never suffer from fever, nose‐blocking or sneezing and I can see that breast milk is really healthy food for him” | Breastfeeding stopped abruptly at 6 months |

| Urban 47: | |||||||

|

Age: 39 years Education level completed: grade 12 Still at school: no Employed: yes |

Main source of drinking water: piped inside the house Toilet type: flush toilet inside the house Household connected to electricity: yes |

Number of ANC visits: three Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Currently taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EBF | “I would not be able to afford formula” | 5 months | “I noticed that she's crying a lot and I think maybe it because she's not full then I decided, let me try feeding him the small purity [baby food], you know then she ate it and finished the whole bottle and I realised that oh the problem was in his stomach because after he finished eating purity he didn't cry that much” | Breastfeeding continued, mother plans to continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months |

| Urban 48: | |||||||

|

Age: 18 years Education level completed: grade 12 Still at school: no but intends to continue with her education Employed: no Relationship status: NOT still in a relationship with the father |

Main source of drinking water: piped inside the house Toilet type: flush toilet inside the house Household connected to electricity: yes |

Number of ANC visits: four Visited by a CHW during pregnancy: no Taking ART: yes HIV status disclosed to significant others: yes |

EFF |

“I knew that I cannot breastfeed. One, because of my status, it's too risky, the chance of him contracting it (HIV), uh, it is great. They (nurses) might not say it (is) that great but … I don't want to take a chance. Two, because I want to go and work, he's still young I have to work and provide for him” |

Not applicable | ||

Note. CHW: community health workers; ART: antiretroviral therapy; EBF: exclusively breastfeed; EFF: exclusively formula feed; ANC: antenatal clinics.

All mothers were on ART during pregnancy and throughout breastfeeding, and most (7/11) had disclosed their HIV status to significant others. Three major themes emerged from the analysis of the transcripts: the role of HWs in provision of infant feeding advice; fear of HIV transmission influences feeding choices; importance of mothers' self‐efficacy to resist pressures from family and community to change her feeding practice.

3.1. Role of health workers in infant feeding decision‐making

The strongest theme that emerged from the data was the important and primary role HWs played in guiding HIV‐infected mothers in decision‐making around infant feeding. Several mothers reported only deciding to breastfeed upon receiving HW advice about infant feeding (Table 1) “No, I didn't know I was going to breastfeed as I thought only [HIV] negative people were allowed to breastfeed, until I visited the clinic” (Urban 07, Month 2).

HWs were the main source of feeding advice for mothers, starting during ANC, with EBF for 6 months being the clear and dominant message communicated to mothers. “When we were at the clinic, we started by learning about feeding the baby for 6 months, not giving him water but make him drink breastmilk only” (Urban 07, Month 2). Most mothers followed HWs feeding advice diligently, and this advice continued to be the main source of information and influence on mothers feeding decision‐making throughout the six‐month observation period. “I'm waiting for Monday to go for 6 months [clinic] visit, then they will tell me what to do” (Urban 47, Month 6).

Most mothers revealed they did not change their feeding plan without consulting the clinic first. “I don't know when I can stop breastfeeding him, I will hear from the clinic or they will say I must stop him or what, I don't know” (Rural 02, Month 2). In several cases, mothers showed that the advice given by HWs led them to a clear understanding of the current guidelines for HIV and infant feeding.

I must not give him anything except breast milk because there is a part there, I don't know where it is, but when I give the baby other food it can be easy for the baby to be [HIV] infected. Unlike when I'm exclusively breastfeeding it not easy for the baby to be infected, and then I give him that medicine they gave me to give him. (Rural 11, Month 2)

3.1.1. High level of trust in health workers advice

When we explored whether there were other key individuals from whom mothers sought advice, most mothers consistently emphasised they only took advice from HWs. A rural mother who was EBF, stated: “No I won't listen to those people, I will listen to people from the hospital because they have knowledge (she laughs)” (Rural 11, Month 1).

The main reason stated by mothers for following HWs' advice carefully, despite sometimes receiving contrary advice from their family and community, was that by following HWs' recommendations mothers believed they could prevent their infants from becoming HIV‐infected. This provided strong motivation for mothers to listen to HWs advice. One mother who EBF for 6 months emphasised the “danger” of suboptimal feeding practices:

They [nurses] said that I must only breastfeed the baby, then give him medicine [ART] because it is dangerous to give him other things, it can cause him to get the virus. But if I breastfeed him exactly like what they taught me it can prevent him from getting the virus. (Rural 11, Month 2)

HWs also advised about the important link between breastfeeding and ART compliance, with several mothers mentioning ART was given to protect the baby from acquiring HIV, and it was only safe to breastfeed if the medicine was taken regularly.

They (HWs) motivated us that it is rare to find the baby like that [HIV infected], but we must make sure that you use the treatment properly, that they give you to protect you and the baby. (Rural 04, Month 5)

However, at times, there were important limitations in both quality and quantity of infant feeding counselling mothers received from HWs. All mothers attended ANC, and most had attended at least four visits, and reported receiving infant feeding counselling during these visits. However, this counselling was usually conducted in groups, providing little opportunity for individual counselling to address individual queries for HIV‐positive mothers. As a result, some mothers reported that their specific concerns were not addressed, for example one mother talked about her concern regarding breast sores, and whether these could develop during breastfeeding and put the infant at risk of contracting HIV. This concern was not resolved, and the mother decided to formula feed (Table 1). When this was explored further, this mother reported that she tested HIV‐positive before her pregnancy and had not received counselling from her clinic: “I read books after I found out I am positive, on how should I live. There is no one I can say he or she taught me” (Rural 18, Month 2).

Mothers reported that HWs strongly advised them to breastfeed. “They [nurses] said we must breastfeed the babies for six months because if we do so, the baby will not get [HIV] infected. It is a rule to breastfeed the baby for six months” (Rural 09, Month 3). However, mothers did not report receiving information about alternative feeding options and received little or no information about the risk of postnatal transmission.

I decided myself on how to feed the baby. Oh, they do teach you at the clinic when you pregnant but they don't teach you how to feed the baby, they only teach you about the importance of breast milk. (Rural 18, Month 3)

As a result, HWs did not provide mothers with information about formula feeding, or support those mothers who decided to formula feed. Two mothers decided to formula feed (Table 1), making the decision themselves that the risk of HIV transmission from breastmilk was too great, and they did not wish to breast feed. “Yah I don't want to take the chance” (Urban 48, Month 2).

M: It was the sister [nurses], they told me that breast milk is important for the baby whether you [are] positive or negative but breast milk is number one. That is what they told me but I decided that, no, I must give him this [formula] milk. (Rural 18, Month 2)

Neither of these mothers reported receiving support for this decision or advice about how to formula feed.

No one taught me sister, but I figured it out myself because I know that I have to clean his cup with soap, put it in boiled water, then I measure milk using formula spoons, then I pour boiled water using the measuring numbers. (Rural 24, Month 1)

One of these mothers had to breastfeed during her hospital stay because she believed there was no formula milk available at the hospital (Rural 18). As a result, she breastfed for 3 days until she got home before switching to exclusive formula feeding. The second mother who planned to formula feed also talked about the counselling she received in hospital regarding her decision to EFF:

No, they just don't like formula feeding in that hospital, that is what I noticed. They don't … talk about it that much, they focus more on breastfeeding. If you going to formula feed they say ‘ok fine, formula feeding, feeding‐cup’ that's all they say. And they don't promote dummy, teats and all that, but besides that, it was just breastfeeding one way, breastfeeding one way. (Urban 48, Month 1)

3.1.2. Lack of HW support for breastfeeding challenges

Ongoing support for challenges experienced with breastfeeding during the postnatal period also appeared to be lacking. The most common challenge expressed, and the main reason reported by several mothers for adding other food/fluids, was that the mother perceived her milk to be insufficient for the needs of the baby, leading her to either mixed feed or stop breastfeeding early (Table 1).

Yah, I noticed that he's crying a lot and I think maybe it because he's not full. Then I decided, let me try feeding him the small purity [baby food], you know. Then he ate it and finished the whole bottle and I realised that, oh, the problem was in his stomach because after he finished eating purity he didn't cry that much. (Urban 47, Month 5)

In addition, messages shared by HWs were sometimes outdated. Most participants held a firm understanding that breastfeeding stops with the introduction of other food “I must breastfeed him exclusively until he stops (breastfeeding), at that time when I will stop him then I can give him food. If I'm still breastfeeding him I cannot give him other foods” (Rural 11, Month 2). This was not in line with recommendations at the time of the study, which stated HIV‐nfected mothers should add nutritious complementary foods at 6 months and continue breastfeeding to 12 months.

3.2. Fear of HIV transmission influenced feeding choices

Mothers frequently expressed they were fearful as a result of the advice and information provided by HWs. In particular, HWs promoted EBF in a way that led mothers to be fearful of mixed feeding. This played out in two ways, firstly it provided strong encouragement for EBF and led some mothers to be very committed to ensuring they complied with the feeding advice given.

I would have chosen to breastfeed him for six months even though the baby's father has the money [to buy formula], I'm scared of his life. I would have chosen to breastfeed him because we were told that when the baby is 5 years … he usually gets sick and most of them die, that's what they [nurses] said. (Urban 07, Month 6)

However, in some cases, this meant that mothers became so fearful of mixed feeding, including even the possibility that the baby could be given other food by another carer, that they stopped breastfeeding entirely. One working mother, who was going back to work, stated that this was her way of ensuring the baby was not mixed fed when she was away, and therefore “safe” from getting HIV.

I don't want to mixed feed because I know the disadvantages. Only if I know how to express, because right now I don't have even a litre in there. What if it [breastmilk] doesn't get enough when I'm at work? Whoever is looking after the baby, it could be the sister, cousin will give her [the baby] water, yet she knows that I'm [HIV] positive but she's not educated about it. She will feed her [the baby], give her tea, when she's eating porridge she will feed her [the baby] and that damages the intestines because the intestines have a protection layer, so if I do all those unwanted things I will destroy everything. (Urban 03, Month 2)

Another mother mentioned how her fear of mixed feed led her to discontinue breastfeeding at once.

I made a decision to stop breastfeeding him yesterday because the milk wasn't coming out of my breasts. He was crying and even when I was expressing nothing was coming out, so I thought it better to stop and feed him formula only, as I didn't want to mixed feed. (Rural 08, Month 4)

The need to be vigilant all the time due to fear of the baby being mixed fed was mentioned as tiring by those who continued to breastfeed even after returning to work. This mother stated:

“It is hard keeping an eye on the baby all the time, but I'm now used to it because I'm thinking about his life” (Urban 07, Month 4).

3.3. Importance of mothers' self‐efficacy in sustaining feeding choice

Several mothers described being pressurised to add other food to the baby's diet by other members of the family or community. Those mothers who succeeded in EBF demonstrated strong self‐efficacy and held to their own beliefs despite facing challenges “when they talk I pretend as if I hear them but I don't do what they are saying” (Rural 08, Month 5).

I do hear them [family members] saying the baby will be hungry, he won't get full, and then I tell them that the rule from the Department of Health says I must breastfeed the baby exclusively until the right time comes to mixed feed him. (Rural 11, Month 4)

Other mothers simply reported they did not discuss anything with other family or friends and just stuck to their own decision to EBF. “No, I haven't discussed anything because I am a strong person, I've told myself that I am going to breastfeed so there is no one that I fought with or say something” (Urban 03, Month 2).

However, there were mothers who reported receiving pressure from family members, which led directly to the mother adding other food or fluids.

They [my family] said I must stop breastfeeding him and give him infant formula, maybe he'll get full …. They said our kids will die if we keep on listening to the nurses because you will find that their [nurses] kids are eating and ours are not. (Rural 08, Month 2)

Disclosure of HIV status was a factor that helped mothers to get support from family members on their choice to EBF. A mother from the urban area narrated:

I told them [family members] that they must never feed the baby anything because my brother's baby died when he was 5 years. He had HIV. I told them that I was instructed to breastfeed him for 6 months because when we mixed feed he might die too when he is 5 years, maybe he will suffer from diarrhoea just like he did, so they are scared. (Urban 07, Month 4)

4. DISCUSSION

Concern to prevent the baby acquiring HIV through breastfeeding was always at the core of HIV‐positive women's infant feeding choices and, as a result, they followed HWs advice diligently. HWs were perceived as knowledgeable professionals who could be relied on to provide the “correct” information. The importance of listening to HWs and resisting contrary advice from other family or friends was emphasized by most participants. The message of EBF for 6 months was strongly promoted and clearly received and understood by mothers and, as a result, most mothers chose to EBF. However, mothers often perceived this as an instruction, “it is the rule,” rather than an informed choice. Mothers continued to rely on HWs advice throughout the first 6 months, with several mothers explaining they did not make any decision without first consulting the clinic. The strong reliance on HWs advice provides an opportunity to effectively support optimal feeding practices, because it makes it likely that good quality infant feeding messages and support from HW s would be heeded by mothers. The importance of HW support has been documented among HIV‐positive mothers in other settings, as has the tendency for HWs to instruct mothers how to feed rather than counselling them about feeding choices (Chaponda et al., 2017; Hazemba, Ncama, & Sithole, 2016; Doherty, Chopra, Nkonki, Jackson, & Greiner, 2006).

However, suboptimal counselling practices were identified, and because of mothers' dependence on HWs advice, this led to adoption of incorrect feeding practices. In particular, there was a very strong message about the negative consequences of mixed feeding, with most mothers believing that mixed feeding should be avoided at all costs. In several cases, this had the unintended consequence that when a mother felt unable to maintain EBF, for example because of returning to work or because she believed the baby was not getting enough food, she preferred to stop breastfeeding immediately rather than mixed feed or seek advice. In addition, HWs and mothers were confused about the recommendation to continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months, as this was directly in contradiction to the message about the dangers of mixed feeding, and led to HWs being uncertain about what to advice to give mothers as the child reached 6 months. Several studies in other settings have also shown that frequent changes to the infant feeding guidelines have resulted in HWs providing confused and inconsistent messages (Chinkonde et al., 2010; Rujumba, Tumwine, Tylleskar, Neema, & Heggenhougen, 2012). Given the importance of HWs advice in supporting mothers feeding choices, further skills development is required to ensure HWs provide clear, appropriate, and relevant messages. In addition, HWs should provide mothers with messages to develop their self‐efficacy and support them to overcome the challenges they are likely to face, for example to counter contrary advice from family members.

The strong advocacy for EBF meant that mothers who chose replacement feeding did not receive comprehensive feeding counselling, contradicting current infant feeding guidelines, which recommend HIV‐positive mothers be informed about feeding options, and those who choose replacement feeding should also receive education and support (South African National Department of Health, 2013b). Mothers who chose formula feed were sidelined, and one mother reported having to give breastmilk, contrary to her infant feeding choice, while in hospital, although DoH policy requires formula milk to be available in hospitals. This highlights the complexity faced by HWs in communicating best feeding choices for HIV‐positive mothers (Zulliger et al., 2013).

Another concern was that antenatal infant feeding counselling was frequently provided in a group setting. Although this is a positive step towards eliminating stigma, the result was that HIV‐positive mothers' concerns were not fully addressed. Antenatal intention to breastfeed has been shown to be a crucial determinant of success in EBF (Doherty et al., 2012), so it is important for HWs to create opportunities for individual feeding counselling for all mothers during the antenatal period, with the aim of encouraging mothers to make a firm infant feeding decision before the baby is born. HIV‐positive mothers also require individual counselling and support for HIV care, particularly ART adherence, if HIV transmission is to be avoided. Thus, providing comprehensive and integrated support for these mothers, encompassing both HIV care and infant feeding, is crucial for the health and well‐being of both mother and baby. However, the shortage of professional HWs is a challenge to providing individual counselling time. Peer counselling has been successfully used to provide individual support, in South Africa and elsewhere, and this could provide a platform to address individual concerns by peers who understand the situation faced by mothers (Sudfeld, Fawzi, & Lahariya, 2012). Support groups for HIV‐positive mothers could also provide support and advice in a safe environment (Rujumba et al., 2012; Luque‐Fernandez et al., 2013). In addition, community based advocacy and mobilisation could be employed to develop a supportive enabling environment for breastfeeding in the community.

Another challenge was providing timeous support to mothers experiencing challenges maintaining breastfeeding during the postnatal period. Generic messages supporting breastfeeding are insufficient to ensure that EBF is sustained for 6 months, mothers require individually tailored support for their challenges as these inevitably arise. Perceptions that the mother has insufficient breastmilk is a key challenge to sustaining EBF. This has been widely described (Fjeld et al., 2008; Chaponda et al., 2017; Jama et al., 2017; Talbert et al., 2016), and it is often combined with pressure from family members to give the baby other foods. This situation can arise quickly, and mothers require counselling support and reassurance to assist them to sustain breastfeeding, and this support needs to be accessible and available when required. Overworked facility‐based HWs are inaccessible and ill‐equipped to provide this support. Community health workers (CHWs) are deployed in many communities and have a key role in providing support to mothers in the household. CHW support has been shown to be successful in improving breastfeeding practices, (Horwood et al., 2017) and mothers have expressed appreciation of the CHWs role (Wilford et al., 2018). CHWs are well placed to provide accessible, appropriate, timeous support, and to address conflicting pressures from family members, and build the mothers confidence in her ability to EBF that is crucial for success (Minas & Ganga‐Limando, 2016). However, in our small sample, only three women, all from the rural area, reported having been visited by a CHW during pregnancy. This is similar to CHW coverage described in other studies (Horwood et al., 2018), and suggests that the CHW programme in KZN needs strengthening if CHWs are to provide effective support for breastfeeding.

HWs strong role in influencing feeding practices suggests that there is a realistic expectation that mothers will adhere to the advice given. However, it also highlights how crucial it is for HWs to be knowledgeable about the most current guidelines, to avoid misinformation leading to confusion and suboptimal feeding practices. Reasons for poor counselling quality may be lack of training, outdated information, uncertainty among HWs about how to manage breastfeeding challenges, or mothers who choose to formula feed (van Rensburg et al., 2016; Chinkonde et al., 2009; Moland et al., 2010a, 2010b). HWs have expressed the need for more training, but it is a constant struggle to keep HWs up to date with ever‐changing guidelines (Rujumba et al., 2012; Mkontwana, Steenkamp, & Von der Marwitz, 2013). HWs often work in isolated inaccessible areas, and frequent trainings are costly and resource intensive. In any case, training alone has been shown not to result in sustained changes in HW practice (Haines, Kuruvilla, & Borchert, 2004). Innovative solutions should be sought to ensure that HWs receive information about changes to guidelines in an appropriate and acceptable way. These solutions require rigorous evaluation to ensure their effectiveness. Using short messaging services (SMS) on cell phones as a way of providing messages has been successfully implemented with mothers (Zunza, Cotton, Mbuagbaw, Lester, & Thabane, 2017), and to improve treatment adherence in low resource settings (Mbuagbaw et al., 2013), so could similarly be used to provide health workers with accessible updates.

Fear of the baby becoming HIV infected played a strong role in motivating mothers to comply with recommended feeding practices. In some cases, HWs used fear to persuade mothers to comply with advice, a commonly used tactic in health campaigns, particularly in those relating to HIV (Muthusamy, Levine, & Weber, 2009). However, it is suggested that where high levels of fear already exist, the use of such tactics may be counterproductive and induce heightened anxiety and impaired decision‐making. However, fear is also a response that drives people to action, and can lead to increased motivation to counter the threat, as shown by many participants in our study. This is dependent on the person's belief in their ability to mitigate the threat. If a person is fearful and lacks self‐ efficacy, they may resort to actions to reduce fear rather than actions that mitigate the threat, for example denial or defensive avoidance (Witte & Allen, 2000). This suggests that HWs should combine information that may lead mothers to become fearful with strong messages to improve the mothers' self‐efficacy, providing encouragement and support for her ability to successfully EBF. Many of the mothers in our study demonstrated high levels of self‐efficacy, and were able to resist contrary advice about feeding. Using fear as a tactic can strengthen an intervention, but it has its dangers, and if combined with misinformation, it is clearly counterproductive.

The major strength of this study is the strong methodology, which allowed us to prospectively explore the reasons for infant feeding decision‐making. We had little loss to follow‐up, with 10 of 11 participants completing the six‐month follow‐up period, and only two participants who failed to participate in all six scheduled visits. However, a weakness is that we may not have taken full advantage of the longitudinal nature of the study by failing to fully apply an iterative approach and adapting data collection tools based on findings of a concurrent analysis. Our fieldworkers, despite training and quality control, were not researchers, and they lacked the ability to consider the overall study aims during interviews, so the quality of the interview data may have been reduced.

5. CONCLUSION

Optimising infant feeding practices for HIV‐positive mothers remains a public health issue in South Africa and globally, as the fight against malnutrition and child morbidity and mortality continues. Our findings suggest a major shift towards uptake of breastfeeding as a feeding strategy for HIV‐positive mothers. Breastfeeding support can be provided through a variety of different approaches including CHWs, peer counsellors, and breastfeeding support groups. However, HWs are the main drivers of feeding practices, and despite HW shortages, provision of breastfeeding support should be considered a priority throughout ANC and postnatal care.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

CH, NJ and LH conceptualised the study and designed data collection methods. NJ collected and analysed the qualitative data. CH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LH, NJ, AC and LS contributed to reviewing drafts and provided critical insights. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the funding contribution from ELMA foundation. We would like to thank the KZN Department of health for their support with this project, and the staff at the recruiting antenatal clinics for their assistance. In particular, we are very grateful to the mothers who participated for allowing us to visit them in their homes and who shared their experiences over such a long period of follow‐up.

Horwood C, Jama NA, Haskins L, Coutsoudis A, Spies L. A qualitative study exploring infant feeding decision‐making between birth and 6 months among HIV‐positive mothers. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12726 10.1111/mcn.12726

REFERENCES

- Calman, L. , Brunton, L. , & Molassiotis, A. (2013). Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: Lessons learned and recommendations for health services research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 14 10.1186/1471-2288-13-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaponda, A. , Goon, D. T. , & Hoque, M. E. (2017). Infant feeding practices among HIV‐positive mothers at Tembisa hospital, South Africa. The African Journal of Primary Health & Family Medicine, 9(1), e1–e6. 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, T. , Knight, S. , Giddy, J. , Crankshaw, T. L. , Butler, L. M. , & Newell, M. L. (2012). A retrospective study of Human Immunodeficiency virus transmission, mortality and loss to follow‐up among infants in the first 18 months of life in a prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission programme in an urban hospital in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. BMC Pediatrics, 12, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikhungu, L. C. , Bispo, S. , Rollins, N. , Siegfried, N. , & Newell, M. L. (2016). HIV‐free survival at 12‐24 months in breastfed infants of HIV‐infected women on antiretroviral treatment. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 21(7), 820–828. 10.1111/tmi.12710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkonde, J. R. , Sundby, J. , de Paoli, M. , & Thorsen, V. C. (2010). The difficulty with responding to policy changes for HIV and infant feeding in Malawi. International Breastfeeding Journal, 5, 11 10.1186/1746-4358-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkonde, J. R. , Sundby, J. , & Martinson, F. (2009). The prevention of mother‐to‐child HIV transmission programme in Lilongwe, Malawi: Why do so many women drop out. Reproductive Health Matters, 17(33), 143–151. 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33440-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, R. , Sinha, B. , Sankar, M. J. , Taneja, S. , Bhandari, N. , Rollins, N. , … Martines, J. (2015). Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(S467), 96–113. 10.1111/apa.13102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovadia, H. M. , Rollins, N. C. , Bland, R. M. , Little, K. , Coutsoudis, A. , Bennish, M. L. , & Newell, M. L. (2007). Mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV‐1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: An intervention cohort study. Lancet, 369(9567), 1107–1116. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60283-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2017). Republic of South Africa: Circular minute no. 3 of 2017/18. HIV/Aids, TB & MCWH: Amendment of the 2013 Infant and Young Child Feeding Policy.

- Doherty, T. , Chopra, M. , Jackson, D. , Goga, A. , Colvin, M. , & Persson, L. A. (2007). Effectiveness of the WHO/UNICEF guidelines on infant feeding for HIV‐positive women: Results from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. AIDS (London, England), 21(13), 1791–1797. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32827b1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T. , Chopra, M. , Nkonki, L. , Jackson, D. , & Greiner, T. (2006). Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: "When they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me". Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84(2), 90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T. , Sanders, D. , Goga, A. , & Jackson, D. (2011). Implications of the new WHO guidelines on HIV and infant feeding for child survival in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89(1), 62–67. 10.2471/BLT.10.079798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T. , Sanders, D. , Jackson, D. , Swanevelder, S. , Lombard, C. , Zembe, W. , … For the PROMISE EBF study group (2012). Early cessation of breastfeeding amongst women in South Africa: An area needing urgent attention to improve child health. BMC Pediatrics, 12, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjeld, E. , Siziya, S. , Katepa‐Bwalya, M. , Kankasa, C. , Moland, K. M. , & Tylleskar, T. (2008). “No sister, the breast alone is not enough for my baby” a qualitative assessment of potentials and barriers in the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in southern Zambia. International Breastfeeding Journal, 3, 26 10.1186/1746-4358-3-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M. P. , Shearer, K. , Maskew, M. , Meyer‐Rath, G. , Clouse, K. , & Sanne, I. (2014). Attrition through multiple stages of pre‐treatment and ART HIV care in South Africa. PLoS One, 9(10), e110252 10.1371/journal.pone.0110252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N. K. , Heath, G. , Cameron, E. , Rashid, S. , & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumede‐Moyo, S. , Filteau, S. , Munthali, T. , Todd, J. , & Musonda, P. (2017). Implementation effectiveness of revised (post‐2010) World Health Organization guidelines on prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV using routinely collected data in sub‐Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review. Medicine (Baltimore), 96(40), e8055 10.1097/MD.0000000000008055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines, A. , Kuruvilla, S. , & Borchert, M. (2004). Bridging the implementation gap between knowledge and action for health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(10), 724–731. discussion 732 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazemba, A. N. , Ncama, B. P. , & Sithole, S. L. (2016). Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding among HIV‐positive mothers: An exploratory qualitative study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 11, 9 10.1186/s13006-016-0068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood, C. , Butler, L. , Barker, P. , Phakathi, S. , Haskins, L. , Grant, M. , … Rollins, N. (2017). A continuous quality improvement intervention to improve the effectiveness of community health workers providing care to mothers and children: A cluster randomised controlled trial in South Africa. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 39 10.1186/s12960-017-0210-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood, C. , Haskins, L. , Engebretsen, I. , Phakathi, S. , Connolly, C. , Coutsoudis, A. , & Spies, L. (2018). Improved rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 14 weeks of age in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: What are the challenges now? BMC Public Health, 18, 757 10.1186/s12889-018-5657-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jama, N. A. , Wilford, A. , Haskins, L. , Coutsoudis, A. , Spies, L. , & Horwood, C. (2018). Autonomy and infant feeding decision‐making among teenage mothers in a rural and urban setting in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 52 10.1186/s12884-018-1675-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jama, N. A. , Wilford, A. , Masango, Z. , Haskins, L. , Coutsoudis, A. , Spies, L. , & Horwood, C. (2017). Enablers and barriers to success among mothers planning to exclusively breastfeed for six months: A qualitative prospective cohort study in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12, 43 10.1186/s13006-017-0135-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health (2015a). Umkhanyakude District health plan 2015–2016 (p. 137). Umkhanyakude: KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health (2015b) Ethekweni District Health Plan 2015‐2016. In. KwaZulu‐Natal Department of Health, 120.

- Luque‐Fernandez, M. A. , Van Cutsem, G. , Goemaere, E. , Hilderbrand, K. , Schomaker, M. , Mantangana, N. , … Boulle, A. (2013). Effectiveness of patient adherence groups as a model of care for stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One, 8(2), e56088 10.1371/journal.pone.0056088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B. , Roe, B. E. , & Fein, S. B. (2010). The differential effects of full‐time and part‐time work status on breastfeeding. Health Policy, 97(1), 79–86. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw, L. , van der Kop, M. L. , Lester, R. T. , Thirumurthy, H. , Pop‐Eleches, C. , Ye, C. , … Thabane, L. (2013). Mobile phone text messages for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): An individual patient data meta‐analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open, 3(12), e003950 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minas, A. G. , & Ganga‐Limando, M. (2016). Social‐cognitive predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among primiparous mothers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One, 11(10), e0164128 10.1371/journal.pone.0164128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkontwana, P. , Steenkamp, L. , & Von der Marwitz, J. (2013). Challenges in the implementation of the infant and young child feeding policy to prevent mother‐to‐child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in the Nelson Mandela Bay District. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 26(2), 25–32. 10.1080/16070658.2013.11734447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mnyani, C. N. , Tait, C. L. , Armstrong, J. , Blaauw, D. , Chersich, M. F. , Buchmann, E. J. , … McIntyre, J. A. (2016). Infant feeding knowledge, perceptions and practices among women with and without HIV in Johannesburg, South Africa: A survey in healthcare facilities. International Breastfeeding Journal, 12, 17 10.1186/s13006-017-0109-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moland, K. M. , van Esterik, P. , Sellen, D. W. , de Paoli, M. M. , Leshabari, S. C. , & Blystad, A. (2010a). Ways ahead: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in the context of HIV. International Breastfeeding Journal, 5, 19 10.1186/1746-4358-5-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moland, K. M. , de Paoli, M. M. , Sellen, D. W. , van Esterik, P. , Leshabari, S. C. , & Blystad, A. (2010b). Breastfeeding and HIV: experiences from a decade of prevention of postnatal HIV transmission in sub‐Saharan Africa. International Breastfeeding Journal, 5, 10 10.1186/1746-4358-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthusamy, N. , Levine, T. R. , & Weber, R. (2009). Scaring the already scared: Some problems with HIV/AIDS fear appeals in Namibia. Journal of Communication, 59(2), 317–344. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paoli, M. M. D. , Mkwanazi, N. B. , Richter, L. M. , & Rollins, N. (2008). Early cessation of breastfeeding to prevent postnatal transmission of HIV: A recommendation in need of guidance. Acta Paediatrica, 97(12), 1663–1668. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz, E. G. , Ferguson, Y. O. , Bentley, M. E. , Corneli, A. L. , Moses, A. , Nkhoma, J. , … UNC Project BAN Study Team (2006). Differences between international recommendations on breastfeeding in the presence of HIV and the attitudes and counselling messages of health workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. International Breastfeeding Journal, 1(1), 2 10.1186/1746-4358-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis, B. , Cole, D. C. , van Lettow, M. , Escobar, M. , Muula, A. S. , Ahmad, F. , … Chan, A. K. (2014). Follow‐up visit patterns in an antiretroviral therapy (ART) programme in Zomba, Malawi. PLoS One, 9(7), e101875 10.1371/journal.pone.0101875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. , & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The Qualitative Researcher's Companion, 573(2002), 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet, 387(10017), 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujumba, J. , Tumwine, J. K. , Tylleskar, T. , Neema, S. , & Heggenhougen, H. K. (2012). Listening to health workers: Lessons from Eastern Uganda for strengthening the programme for the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 3 10.1186/1472-6963-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. H. , Coley, S. L. , Labbok, M. H. , Cupito, S. , & Nwokah, E. (2012). Early breastfeeding experiences of adolescent mothers: A qualitative prospective study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 7(1), 13 10.1186/1746-4358-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Africa National Department of Health (2013a). South African national antenatal sentinel HIV prevalence survey. Pretoria: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa National Department of Health (2013b). Infant and young child feeding policy. Pretoria: South Africa National Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa National Department of Health . (2014). National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. In. Edited by SA Department of Health. Pretoria.

- Sudfeld, C. R. , Fawzi, W. W. , & Lahariya, C. (2012). Peer support and exclusive breastfeeding duration in low and middle‐income countries: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One, 7(9), e45143 10.1371/journal.pone.0045143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbert, A. W. , Ngari, M. , Tsofa, B. , Mramba, L. , Mumbo, E. , Berkley, J. A. , & Mwangome, M. (2016). "When you give birth you will not be without your mother" a mixed methods study of advice on breastfeeding for first‐time mothers in rural coastal Kenya. Inerternational Breastfeeding Journal, 11, 10 10.1186/s13006-016-0069-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2016). For every child, end AIDS–seventh stocktaking report. New York, NY: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Decade of Nutrition 2016‐2025 . (2016). Available from: [http://www.who.int/nutrition/decade-of-action/en/]

- van Rensburg, L. J. , Nel, R. , & Walsh, C. M. (2016). Knowledge, opinions and practices of healthcare workers related to infant feeding in the context of HIV. Health SA Gesondheid, 21, 129–136. 10.4102/hsag.v21i0.943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. , Franca, G. V. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , et al. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilford, A. , Phakathi, S. , Haskins, L. , Jama, N. A. , Mntambo, N. , & Horwood, C. (2018). Exploring the care provided to mothers and children by community health workers in South Africa: Missed opportunities to provide comprehensive care. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 171 10.1186/s12889-018-5056-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K. , & Allen, M. (2000). A meta‐analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615. 10.1177/109019810002700506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (2001). New data on the prevention of the mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV and their policy implications: Conclusions and recommendations: WHO technical consultation on behalf of the UNFP.

- World Health Organisation . (2006). Infant feeding technical consultation held on behalf of the inter‐agency task team (IATT) on prevention of HIV infections in pregnant women, mothers and their infants. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (2010). Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding 2010: Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation , & United Nations Childrens Fund (2016). Guideline: Update on HIV and infant feeding: the duration of breastfeeding, and the support from health services to improve feeding practices among mothers living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2012). Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. WHO, Geneva, April. [PubMed]

- Zulliger, R. , Abrams, E. J. , & Myer, L. (2013). Diversity of influences on infant feeding strategies in women living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: A mixed methods study. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 18(12), 1547–1554. 10.1111/tmi.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunza, M. , Cotton, M. F. , Mbuagbaw, L. , Lester, R. , & Thabane, L. (2017). Interactive weekly mobile phone text messaging plus motivational interviewing in promotion of breastfeeding among women living with HIV in South Africa: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 331 10.1186/s13063-017-2079-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]