Abstract

Promoting exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is a highly feasible and cost‐effective means of improving child health. Regulating the marketing of breastmilk substitutes is critical to protecting EBF. In 1981, the World Health Assembly adopted the World Health Organization International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (the Code), prohibiting the unethical advertising and promotion of breastmilk substitutes. This comparative study aimed to (a) explore the relationships among Code enforcement and legislation, infant formula sales, and EBF in India, Vietnam, and China; (b) identify best practices for Code operationalization; and (c) identify pathways by which Code implementation may influence EBF. We conducted secondary descriptive analysis of available national‐level data and seven high level key informant interviews. Findings indicate that the implementation of the Code is a necessary but insufficient step alone to improve breastfeeding outcomes. Other enabling factors, such as adequate maternity leave, training on breastfeeding for health professionals, health systems strengthening through the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, and breastfeeding counselling for mothers, are needed. Several infant formula industry strategies with strong conflict of interest were identified as harmful to EBF. Transitioning breastfeeding programmes from donor‐led to government‐owned is essential for long‐term sustainability of Code implementation and enforcement. We conclude that the relationships among the Code, infant formula sales, and EBF in India, Vietnam, and China are dependent on countries' engagement with implementation strategies and the presence of other enabling factors.

Keywords: breastfeeding counselling, conflict of interest, exclusive breastfeeding, maternity protection, WHO Code

Key messages.

Implementation of the Code is a necessary but insufficient action alone to improve breastfeeding outcomes.

Other factors, such as maternity leave, the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, and breastfeeding counselling, also need to be in place to improve breastfeeding behaviours.

Transitioning from donor‐led to government‐owned large‐scale breastfeeding programmes is key to improving breastfeeding practices.

1. INTRODUCTION

Interventions to promote exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) have been identified as highly feasible and cost‐effective for improving child health and development. Globally, only 38% of infants aged 0 to 6 months are exclusively breastfed (Rollins et al., 2016; Victora et al., 2016). To improve maternal and child health outcomes, the 2012 World Health Assembly (WHA) set a global nutrition target to reach at least 50% EBF by 2025. To achieve this goal, a strong breastfeeding friendly environment is needed, with efficacious interventions delivered across key sectors to protect, promote, and support EBF (Cheung, 2018; Rollins et al., 2016; Victora et al., 2016; World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). Experts have concluded that regulating the marketing of breastmilk substitutes is a critical intervention to protect and enable breastfeeding friendly environments (Brady, 2012; Evans, 2018; Rollins et al., 2016).

In 1981, the WHA adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (the Code), which prohibits the advertising and promotion of breastmilk substitutes (WHO, 1981). The marketing of breastmilk substitutes is thought to affect both the breastfeeding behaviours of women and the medical practice of health care workers (Duong, Lee, & Binns, 2005; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Rollins et al., 2016). Piwoz and Huffman (2015) proposed that advertisements influence social norms by promulgating messages suggesting substitutes are as good as or better than breastmilk, thereby diminishing maternal confidence in breastfeeding. The Code is included in the first step of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding for Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) accreditation (WHO, 2018).

In 2016, the WHO published an evaluation of the national legal measures enacted by countries in response to the Code, classifying countries according to five categories: full provisions in law, many provisions in law, few provisions in law, no legal measures, and no information (WHO et al., 2016). These categories are based on whether countries have enacted legally binding measures that encompass provisions of the Code and subsequent WHA resolutions. As of March 2016, 135 countries had some degree of legal measures in place to operationalize the Code (WHO et al., 2016). Some countries have also begun to implement the WHO‐led Network for Global Monitoring and Support for Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (NetCode), which supports the continuous monitoring of the Code (WHO, 2017).

Despite the introduction of the Code, the global sales of breastmilk substitutes and infant formulas increased 41% between 2008 and 2013 and grew as much as 72% in upper‐middle income countries in East Asia and the Pacific during the same time (Baker et al., 2016). This growth in sales is much higher than what would be expected based on population growth and has been associated with rising incomes (Piwoz & Huffman, 2015) in the context of urbanization, female labour‐force participation, and lack of protection and support for working women (Baker et al., 2016; Changing Markets Foundation, 2017).

The impact of the Code on EBF rates and infant formula sales remains unknown (Evans, 2018). WHO periodically publishes status reports on the state of the Code worldwide; however, these reports do not permit in‐depth analyses of Code implementation (WHO, 2016). Case studies often focus on multiple policies that influence breastfeeding, rather than explicitly on the Code (Save the Children, 2018). Studies have relied on literature reviews and have not focused on specific countries or identified pathways for better implementation (Piwoz & Huffman, 2015), and it has been recently recommended to examine country‐level studies on Code implementation and its relation to the breastfeeding landscape, which is a gap this study aims to address (Evans, 2018).

Specifically, this comparative case study aims to (a) explore the relationships among the legislation and enforcement of the Code, infant formula sales, and EBF in India, Vietnam, and China; (b) identify best practices for Code operationalization; and (c) identify pathways by which the implementation of the Code may influence EBF.

2. METHODS

We conducted a comparative case study analysis using mixed methods (Small, 2011), composing of a secondary descriptive analysis of available national‐level data and key informant interviews. This study received Human Subjects Review exemption approval from Yale's Human Subjects Institutional Review Board and was not reviewed by in‐country ethics committees as Yale was the only institution conducting the project.

2.1. Countries' selection

We used purposeful sampling to select three case countries that had adopted the Code but had different EBF prevalences (Patton, 2002). Due to India's success in the implementation of the Code (WHO, 2016), we selected Asia as our region of study. We examined country World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) reports to identify Asian countries with different EBF prevalence and Code implementation; as a result, Vietnam and China were also included (Table S1).

2.1.1. India

India, a lower middle income country in South Asia (World Bank, 2018) is considered to have “full provisions in law” from the Code's perspective (WHO, 2016). India implemented the Code in 1983 with the launch of the Indian National Code for Protection and Promotion of Breastfeeding (Barennes, Slesak, Goyet, Aaron, & Srour, 2016; WHO, 2016). This legislation was further strengthened in 1992 with the adoption and 2003 revision of the Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles, and Infant Foods Act (WHO, 2016). In relation to the enabling environment for breastfeeding, Indian legislation mandates just 12 weeks of paid maternity leave. Moreover, there are no hospitals certified as Baby Friendly (UNICEF, 2017). India has both strong Code implementation and “Good” EBF prevalence of 54.9% (United Nations Children's Fund, Division of Data Research and Policy, 2018; WHO, 2003).

2.1.2. Vietnam

Vietnam, a lower middle income country in Southeast Asia (World Bank, 2018), also has “full provisions in law” (WHO, 2016). Decree 21, passed in 2006, prohibited advertising of breastmilk substitutes for children under 1 year of age (Alive & Thrive, 2012). In 2013, a new advertisement law built upon this law, banning the marketing of breastmilk substitutes for children under 2 years of age (Walters et al., 2016). In terms of breastfeeding environment, Vietnamese legislation mandates 26 weeks of paid maternity leave. Though just 0.4% of births occur in Baby Friendly Hospitals, 100% of primary health care facilities and 100% of districts offer infant and young child feeding (IYCF) counselling (UNICEF, 2017). Vietnam has strong Code implementation but only a “Fair” EBF prevalence of 24% (UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding, 2013; WHO, 2003).

2.1.3. China

China, an upper‐middle income country in East Asia (World Bank, 2018), was classified as having “few provisions in law” in 2016 (WHO, 2016). China attempted to promote breastfeeding behaviours by adopting the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes Management Measures in 1995 (Tang et al., 2014). However, the Chinese government abandoned the Code from its ministerial regulations in 2017 with little justification (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2017). In relation to the enabling environment for breastfeeding, only 14 weeks of paid maternity leave are guaranteed in China. Twelve per cent of births occur in Baby Friendly Hospitals (UNICEF, 2017). China has a history of weak Code legislation and implementation and a “Fair” EBF prevalence of just 20.8% (UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding, 2013; WHO, 2003).

2.2. Countries' comparison of national‐level data

We obtained data on Code enforcement from WBTi reports published on India, Vietnam, and China. We elected to use EBF data from the UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding, from 2015 to 2016 (India), 2014–2015 (Vietnam), and 2013 (China), as it provided data on standardized infant feeding from all three countries (United Nations Children's Fund, Division of Data Research and Policy, 2018). Other sources consulted for national‐level EBF data, including the Rapid Survey on Children and Demographic and Health Surveys, are detailed in Table 1. Infant formula sales data were gathered from the comprehensive Euromonitor data from 2014. Using these data, we compared prevalence of EBF, strength of Code legislation and enforcement, and infant formula sales across countries.

Table 1.

Sources consulted for country‐level exclusive breastfeeding data

| India | National Family Health Survey (2015–2016, 2005–2006) |

| Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (2000, 1995–1996) | |

| Rapid Survey on Children (2013–2014) | |

| District Level Household Facility Survey (2007–2008) | |

| Vietnam | Demographic and Health Surveys (2002) |

| UNICEF General Nutrition Survey (2009–2010) | |

| UNICEF, State of the World's Children (2014, 2006, 2002) | |

| China | China National Health Service Survey (NHSS) (2008, 2013) |

| UNICEF, State of the World's Children (2008, 2003) |

2.3. Qualitative key informant interviews

Key informants were invited to participate if they met the following criteria: (a) in‐depth knowledge of breastfeeding in the regions of interest, (b) knowledge of Code implementation in the countries of interest, or (c) experience with Code implementation worldwide. Each key informant was extended an invitation to be interviewed for approximately 45 min during the months of February and March 2018. Interviews were semistructured, and the interviewer (H. R.) utilized an interview guide (Appendix A). Interviews were conducted via Skype and lasted an average of 42 min (range 39 to 47 min). The interviews were recorded and transcribed by a professional service. After receipt of the written transcripts, the interviewer checked the written transcripts against the original audio recording to ensure accuracy.

2.3.1. Analysis

We conducted thematic analysis involving a systematic coding process performed by three members of the research team (H. R., G. B., R. P. E.) who independently coded one interview using Microsoft Word and worked together to reach consensus on the appropriate codes. This process was repeated systematically for six of the seven interviews leading to the final codebook with themes, subthemes, and operational definitions. We refined the codebook iteratively and vetted with the team multiple times to ensure transparency and agreement on code organization. Thematic saturation was reached, as the coding of the final two interviews yielded no additional themes (Morse, 1995).

All interviews were then coded on Dedoose v.8 qualitative computer software by a single coder using a consistent coding process and the final codebook.

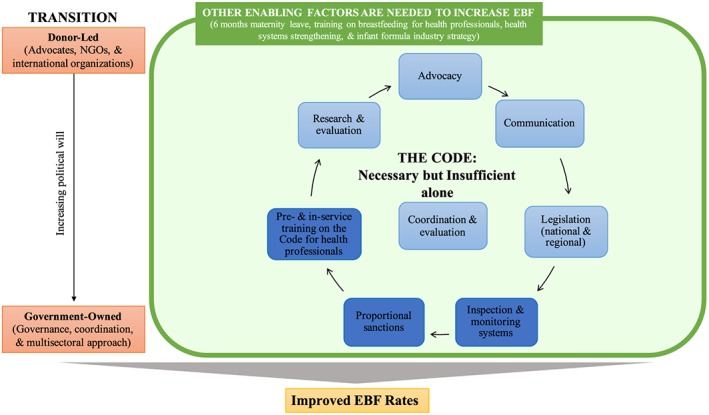

Conceptual categories were generated throughout the coding process (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007; Glaser, Strauss, & Strutzel, 1968). Systematic relationships between conceptual categories were described. The relationships among categories formed a foundation for the development of the conceptual model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model illustrating relationship between themes found in the key informants' interview data: blue: Theme 1 [dark blue: implementation strategies]; green: Theme 2; orange: Theme 3; yellow: impact of actions. EBF: exclusive breastfeeding; NGOs: non‐governmental organizations

3. RESULTS

3.1. Countries' comparison of national‐level data

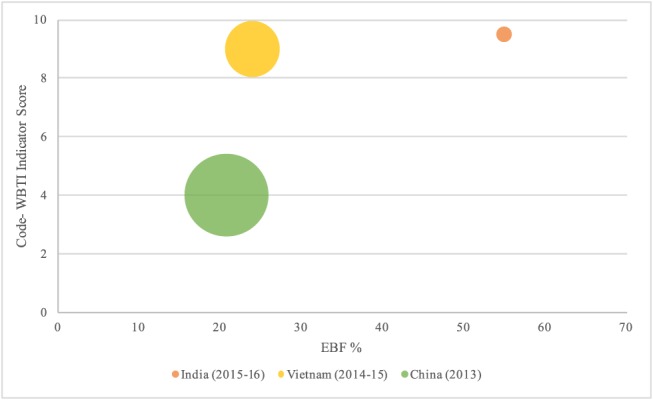

EBF rates varied among the three cases. India presented the highest prevalence of EBF among infants under 5 months of age (54.9%), followed by Vietnam (24%) and China (20.8%). In terms of infant formula sales, China had the greatest formula sales (24.7 kg per capita population 0–6 months) and India the least (0.9 kg per capita population 0–6 months; Euromonitor International, 2015). Regarding the implementation of the International Code of Breastmilk Substitutes, in the 2015 WBTi reports, India and Vietnam both received high scores (9.5 and 9 out of 10, respectively; WBTi, 2015a; WBTi, 2015b). In 2013, China received a much lower score (4/10; WBTi, 2013).

The relationship among EBF, Code WBTi score, and formula sales is represented in Figure 1. A comparison of China and India confirmed the expected pattern that high enforcement of the Code is associated with higher EBF prevalence and lower infant formula sales. For Vietnam, this pattern did not hold as a low EBF prevalence was found despite the high Code implementation score. These findings underscore the need to identify potential pathways though which the Code may affect EBF.

Figure 1.

Relationship among the Code, formula sales, and exclusive breastfeeding. Orange: NFHS‐4, retrieved from UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding. Yellow: MICS, retrieved from UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding; WBTi data from 2015. Green: China National Health Service Survey (NHSS), retrieved from UNICEF Global Database on Infant and Young Child Feeding. Size of bubble represents the size of the infant formula market, expressed as kg milk formula per capita population 0–6 months in 2014 (Euromonitor International, 2015)

3.2. Qualitative key informant interviews

Key informants were formerly and/or currently employed with the World Health Organization, USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Pan American Health Organization, Alive & Thrive, Save the Children, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, and Fundação Oswaldo Cruz in Brazil. As required by our selection criteria, all informants had strong knowledge of the global Code context, and six had extensive knowledge of the countries being compared (2 from China, 2 from Vietnam, 2 about India).

Key informants' collective input is illustrated through a conceptual model grounded on the three major themes identified from the qualitative analysis (Figure 2). First, the legislation and implementation of the Code is a necessary but insufficient step alone to improve breastfeeding rates. Second, other enabling factors are needed for the Code to facilitate EBF. Third, transitioning breastfeeding programmes from donor‐led to government‐owned is essential for long‐term sustainability of Code implementation and enforcement (Figure 2, Table 2).

Table 2.

Themesa and subthemes identified from key informants' interview data

| Theme | Subtheme | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

The Code: Necessary but insufficient: Informants stated that the Code is essential to improving EBF but emphasized that the legislation, implementation, and enforcement of the Code alone is likely not adequate.

The themes within this domain reflect the challenges and opportunities to Code implementation and support the proposition that the Code is necessary but insufficient to improve prevalence of EBF. |

Advocacy | The work of key players, including civil society, NGOs, and international organizations, in support of the legislation, implementation, and enforcement of the Code. |

| Communication | The ways in which information about infant formula, the Code itself, and breastfeeding is disseminated to civil society. | |

| National and regional legislation | The existence and content of laws based on the Code. The creation of strong legislation is a crucial early step to implementing the Code. | |

| Inspection and monitoring systems | Systematic ways to measure compliance to the Code at all levels, in both continuous and intermittent ways. | |

| Proportional sanctions | A Code implementation strategy that would allow relevant bodies to impose sanctions that are both proportional to the egregiousness of the violation and the ability of the individual or company to pay. | |

| Pre‐ and in‐service on the Code for health professionals | Education of health professionals about the Code and their responsibilities to uphold it. | |

| Coordination and evaluation | The ways in which multiple sectors do and should work together to facilitate all aspects of Code implementation and evaluate their successes and failures. | |

| Research and evaluation | Research and evaluation is needed on the relationship between the Code and EBF. | |

|

Enabling factors are needed to increase EBF.

Building off of the idea of the Code as necessary but insufficient and with the understanding that multiple contextual factors are needed to create an enabling environment for breastfeeding, this domain describes key facilitators and barriers to EBF. |

Six months maternity leave | Barrier: Informants cited that inadequate maternity leave (e.g. less than 6 months) is a key barrier to EBF |

| Training on breastfeeding for health professionals | Barrier: Informants indicated that training on breastfeeding more generally is often lacking in curricula. | |

| Health systems strengthening | Facilitator: Increasing the capacity of the hospitals would improve initiation of EBF. | |

| Food industry strategy | Barrier: The strategies of infant formula companies are a key barrier to successful implementation of the Code and improving EBF. | |

| Transition of infant feeding programmes from donor‐led to country‐owned is essential for long‐term sustainability. | Necessary governance‐related changes that must take place in the background to improve the Code's influence on breastfeeding behaviours. In addition to efforts to better legislate, implement, and evaluate the code, it is crucial that such efforts gradually transition from the hands of donors to the hands of governments. |

Themes are in descending order of centrality to research question. EBF: exclusive breastfeeding.

3.3. Theme 1. The Code: Necessary but insufficient

Informants stated that the Code is essential to improving EBF but emphasized that the legislation, implementation, and enforcement of the Code alone is likely not adequate. Other factors crucial to creating an enabling environment for breastfeeding are described in Section 3.4. An expert on global Code monitoring stated,

Strengthening the Code without doing anything about all the other actions—I am not sure you're going to see an improvement. At the same time, you need good maternity protection, and you need workplace citation policies, you need baby‐friendly. I would say that the Code is an important element, but by itself, it's not enough. Necessary, but not sufficient ….

Informants emphasized the challenges and opportunities related to Code advocacy, communication, legislation, and implementation strategies. Key implementation strategies that were identified included development of monitoring and inspection systems, imposing of proportional sanctions, and pre‐ and in‐service training on the Code for health professionals. Coordination and evaluation of all related activities is also seen as central to the success of the Code. Each subtheme is described below and in Table 2.

3.3.1. Advocacy

Even in countries such as India, which have strong Code implementation and relatively high EBF prevalence, non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) and international organizations play a large role in Code implementation efforts, and government involvement is lacking. An informant from the WHO described the situation in India,

It's not that the government runs the system, it's more. They have got a large network of volunteers out there who keep their eye on things and make a lot of noise when they see something.

Informants also pointed to examples of members of civil society assuming an advocacy role, though this varied by country. Experts on China, for example, stated that there were “very, very, very few” advocates for breastfeeding, noting that being identified as an advocate or activist can be somewhat dangerous and that even NGOs are controlled by the government. However, in other countries, such as Vietnam, civil society plays an active role in both supporting breastfeeding and identifying Code violations. Social media in countries such as Vietnam can facilitate advocacy through mother to mother support groups.

3.3.2. Communication

Discussions with key informants suggested that communicating with mothers and their families is important to both the legislation and implementation of the Code. An informant working on Code implementation in Brazil stated that communicating with mothers could empower them and lead to higher EBF prevalence:

I imagine if we work from the perspective of empowering people make them more aware of the infant food marketing strategies and by telling them their products are not so good as they advertise. And by improving this communication perspective, I think the breastfeeding rates will increase highly because we will not only work with the fiscalization [monitoring] or the fighting ….

However, other informants noted that the legalistic and technical language of the Code can be confusing for mothers and suggested that it may be best to disseminate information about breastfeeding to mothers, rather than information on the Code. Nevertheless, key informants also expressed that communication can help to draw attention to violations, publicly shaming companies for predatory marketing, which can aid to prevent egregious violations.

3.3.3. National and regional legislation

The creation of strong legislation is a crucial early step to Code implementation. Informants from China stated that legislation on the Code was abolished at the end of 2017 and has not yet been replaced. Such a decision may have been caused by some of the aspects of the previous legislation having become obsolete, due to government reforms that had abolished many of the ministries included in the legislation.

Informants explained that infant formula companies often take advantage of loopholes in Code legislation. Passing legislation that would cover some of these violations, therefore, is imperative. Informants shared that the WHO has already put out additional guidelines in attempts to close such loopholes, most notably on the marketing of growing up or “follow on” milks.

Several informants cited the potential of harmonizing Code legislation across world regions to ensure higher compliance to and stronger enforcement of the Code. An expert in Code monitoring noted that if legislations were consistent across regions, enforcement could be more comprehensive. They also noted that legislation related to the Code could be included in antiobesity policies and regulations that restrict the marketing of other food items:

When you're working on comprehensive legislation … you could include breastmilk substitutes along with sugar‐sweetened beverages, salty foods, sugary foods, high‐fat foods, and processed foods.

3.3.4. Inspection and monitoring systems

Informants stressed that monitoring systems must be in place that allow governments to identify and respond to violations. They described monitoring as “an absolute prerequisite,” “essential,” and the only way to “make some change to the current trend.” Monitoring systems such as NetCode were described as a best practice for Code implementation, as it allows ministries to take immediate action on Code violations, ultimately leading to fewer violations.

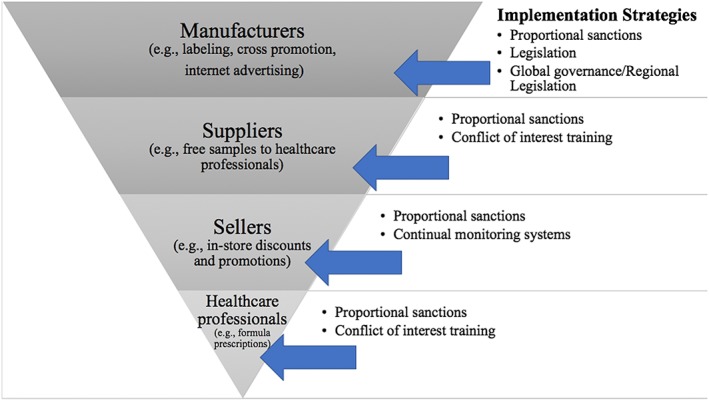

3.3.5. Proportional sanctions

Code violations occur at multiple levels, including those of the manufacturers, suppliers, sellers, and health professionals (Figure 3). Informants noted that even when Code violations are identified, sanctions are either not imposed or the sanction is not proportional to the fiscal resources of the perpetrator and to the nature of the violation. An informant from the WHO described one such scenario, noting that fines have varying influence on actors, based on their ability to pay:

A lot of times people talk about the small fines and that $500 as being just silly, it does not mean anything to the companies, but on the other hand, if that's a fine to a small grocery store, it might be important.

Figure 3.

Levels at which Code violations occur and possible implementation strategies to address each

3.3.6. Pre‐ and in‐service training on the Code for health professionals

Infant formula companies interact with and provide incentives to hospitals and health professionals, creating massive potential for conflict of interest. Pre‐ and in‐service training on the Code is crucial to combating violations at the health professional level (Figure 3). Specifically, informants suggested that pre‐service training, that is, while future professionals are in undergraduate or medical school, is particularly important:

But it's even better if you can manage to put it into pre‐curriculum, so it's not always in‐service training. So, we need to work more on making sure that medical doctors, other health personnel, before they actually get out of the universities, they have learned about it.

Training on the Code can be integrated into ethics curricula and breastfeeding curricula, in both pre‐service and in‐service capacities. Investing in in‐service training would create a platform by which physicians could be informed about updates to Code legislation and changes in food industry strategies.

3.3.7. Coordination and evaluation

Coordination is key to all aspects of Code advocacy, communication, legislation, and implementation and thus stands at the centre of the Code system presented in our conceptual model (Figure 2). Informants stressed that for the Code to be successfully implemented, a multisectoral approach involving various ministries and branches of government is needed. The lack of coordination within government was also as a contributing factor to the ineffectiveness of Code legislation. An informant from Alive & Thrive provided specific details about the need for coordination in Vietnam, stating,

I think the key challenge is the coordination between the agencies within the Ministry of Health. So, in Vietnam, the Ministry of Health has three or four agencies relating to all the practices in health facilities and Code compliance … So, the coordination between the four agencies is not strong.

3.3.8. Research and evaluation

Research and evaluation is needed on the ways in which the Code affects EBF. Informants cited impact studies, in particular, as necessary to understanding if and how the Code impacts EBF and how that impact could be improved. As one informant experienced in programme implementation and evaluation stated, “So, in everything we do, it should be guided by data.” Informants reflected that ongoing evaluation of all Code‐related efforts is essential for the Code to be successful.

3.4. Theme 2. Other enabling factors are needed to increase EBF

Multiple contextual factors are needed to create an enabling environment for breastfeeding. As reflected in the conceptual model (Figure 2), four key enabling factors were identified by the informants: adequate maternity leave, training on breastfeeding for health professionals, health systems strengthening, and breastfeeding counselling for mothers. In addition, one key barrier, infant formula industry strategy, was identified as harmful to EBF.

3.4.1. Six months maternity leave

Informants cited that inadequate maternity leave is a key barrier to EBF, especially in countries such as China that are rapidly developing and witnessing a greater number of women entering the workforce. An informant from Peking University in China described how the inadequate maternity leave policy affects breastfeeding behaviours,

The current maternal leave in our law allows for four months of maternal leave. So, it's less than the six‐month WHO recommendation. So, a lot of people would have to stop breast‐feeding in the fourth month. Or even before.

Formative research in Vietnam undertaken by Alive & Thrive also indicated that inadequate maternity leave was a major barrier to EBF before it was increased from 4 to 6 months in 2012. Alive & Thrive also worked in several regions to create workplace interventions that created an enabling environment for breastfeeding mothers and saw major improvements in EBF rates in those regions.

3.4.2. Training on breastfeeding for health professionals

In addition to training on the Code, informants indicated that training on breastfeeding more generally is often lacking in medical curricula. This leaves providers unable to support breastfeeding mothers, and likely contributes to premature breastfeeding cessation.

Informants from China, in particular, noted that many mothers do not know how to breastfeed and are in need of professional support to overcome breastfeeding difficulties that may otherwise cause them to switch to formula feeding. Efforts to address similar concerns in Vietnam proved successful, when breastfeeding counselling was made available to mothers as part of a larger package to enable breastfeeding. An informant from Alive & Thrive in Vietnam stated,

I think in particular the social franchises, the clinics that could actually provide counseling to mothers, that probably had the best impact ….

3.4.3. Health systems strengthening

Increasing the capacity of the hospitals and working toward BFHI accreditation is another enabling factor for breastfeeding described by the informants. An informant from Peking University described how this lack of human resources can contribute to breastfeeding cessation, stating,

After delivery … they're supposed to be follow up … again, [but] the hospitals do not have the human resource to do that. And there's no other NGOs or community‐supporting groups to do that … So, if [the mothers] have problems or questions or issues with breast‐feeding, they are more like to abandon it, completely stop it and using infant formula.

Moreover, the lifting of the one‐child policy in China poses a unique challenge to the health system, which now requires increased capacity and human resources due to the increasing birth rate. Efforts to strengthen health care systems in India and Vietnam were described as key to enabling a breastfeeding friendly environment. Informants described ways to strengthen health systems, for example, Code compliance can be considered a hospital standard on which insurance reimbursement rates are based.

3.4.4. Infant formula industry strategy

The infant formula industry's attempt at cross promotion (i.e., the promotion of products not covered by the Code that establishes brand loyalty to products covered by the Code) poses a challenge to efforts to increase EBF. An informant from Vietnam explained that “cross promotion by companies is really something that endangers the breastfeeding practice.” Marketing practices engender brand loyalty even during pregnancy by making claims about making children healthier and smarter, which was viewed by informants as harmful to breastfeeding behaviours. An informant from Peking University explained how, even when legislation against advertisement for certain infant formulas was in place, companies were still able to circumvent regulations to foster brand loyalty:

The infant formula companies are not allowed to do an advertisement for the Stage One infant formula, but they can do Stage Two or Stage Three. So, the infant formula companies, they try blur, you know, the difference between Stage One, Stage Two. They just call it infant formula.

3.5. Theme 3. Transition of infant feeding programmes from donor‐led to government‐owned is essential for long‐term sustainability

There was a sense among informants that ownership of large‐scale nutrition and development programmes should be in the hands of governments, transitioning from the hands of donors (i.e., working with but minimizing dependency on international donors). The engagement of international organizations is viewed as finite and technical, providing the resources and expertise for programming that ideally will become implementable by the recipient governments. Empowering governments to take ownership of infant nutrition efforts was viewed as “very much the way forward.” Informants knowledgeable about the extensive Alive & Thrive presence in Vietnam described this organization's approach to ensuring the eventual transition to government ownership, stating,

We were providing technical assistance mostly because it was the government running the programs because we had to focus on sustainability from the start.

To ensure that such a transition occurs in a timely and sustainable manner, advocates must generate political will surrounding breastfeeding. The generation of political will is crucial in light of the infant formula companies' interactions with politicians and governments that create conflicts of interest and may even lead to “political will against [the Code],” as an informant described in China. According to key informants, political will and strong government involvement is needed to facilitate implementation of the Code and the other factors identified as necessary for improving the prevalence of EBF globally.

4. DISCUSSION

The relationships among the legislation and enforcement of the Code, infant formula sales, and EBF in India, Vietnam, and China are dependent on countries' engagement with various implementation strategies and the presence of other factors that enable a breastfeeding friendly environment. Based on our study findings, we developed an innovative and comprehensive conceptual model, identifying possible pathways by which the implementation of the Code may positively affect EBF. This framework indicates that the Code is embedded in a broader system that influences EBF through multiple factors, with the Code being a necessary but insufficient factor alone in improving breastfeeding behaviour, and suggests proposing a new way forward for leveraging the Code to impact EBF.

The conceptual model posited in this paper is in agreement with the breastfeeding gear model (BFGM), which describes the need for multiple actions for the scale‐up and sustainability of breastfeeding programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla, Curry, Minhas, Taylor, & Bradley, 2012). The BFGM highlights the need for evidence‐based advocacy to generate political will, which in turn generates resources to support programme delivery and promotion. The BFGM also stresses the need to conduct research and evaluation to maintain quality and measure effectiveness (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012). The similarities between the BFGM and our conceptual model suggest that the lessons learned here may also help guide discussions on other breastfeeding protection and promotion efforts.

The results of this study are consistent with and advance the knowledge of previous studies related to the Code and the increasing use of breastmilk substitutes worldwide (Baker et al., 2016; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Vinje et al., 2017). The types of violations reported by key informants have been described in the literature as damaging to breastfeeding outcomes, namely, interactions with health professionals, cross promotion, and the use of social media channels for product advertisement (Almroth, Arts, Quang, Hoa, & Williams, 2008; Cheung, 2018; Coutsoudis, Coovadia, & King, 2009; Duong et al., 2005; Liu, Dai, Xie, & Chen, 2014; Morrow, 1996; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Pries et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2014; Vinje et al., 2017). The notion of the Code as necessary but insufficient alone is consistent with other studies. Vinje et al. (2015) did not find an association between milk formula sales and effective dates of regulations on the Code, perhaps because of Code loopholes or the lag between the introduction of policies and changes in beliefs and decisions (Grummer‐Strawn et al., 2017; Vinje et al., 2015). Previous studies stressed the multitude of factors, such as women's involvement in the workforce, maternity leave policies, and availability of BFHI and breastfeeding counselling, that influence infant feeding decisions (Almroth et al., 2008; Duong et al., 2005; Morrow, 1996; Pérez‐Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Tang et al., 2014; Walters et al., 2016; Xu, Qiu, Binns, & Liu, 2009). Finally, the recommendations from this study are consistent with recent reports emphasizing the importance of Code research and monitoring (Evans, 2018).

An innovative recommendation of our study is that efforts related to the Code and improving breastfeeding behaviours be implemented in coordination with antiobesity policies and regulations across countries. Antiobesity efforts in countries such as Chile have sought to change labelling to improve consumer information and combat the rising obesity rate (Boza Martínez, Guerrero, Barreda, & Espinoza, 2017; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2017). Discussions about the importance of marketing regulations are already taking place within countries, and there is opportunity for discussions of marketing of breastmilk substitutes to be included in such conversations and regulations.

These findings must be considered in light of some limitations. First, we were unable to reach a key informant currently working inside India and thus relied on global experts with a good understanding of the Code issues and infant feeding context in India. Second, the recommendations that emerge from this analysis are based on a case study of three countries in Asia, and therefore all countries had, at one point, some provisions in law related to the Code. Therefore, we cannot claim that the findings can be applied universally; specifically, best practices for countries with no history of legislating the Code may deviate from the ones suggested here. However, we mitigated this by including three informants with extensive experience on the Code globally. Their recommendations were consistent with views expressed by in‐country informants, and collectively, information saturation was reached with the interviews conducted.

Future research on how best to enforce the Code to impact breastfeeding behaviours across settings is needed. Research priorities include (a) how best to deal with conflict of interest through strategies targeting health care providers, consumers, infant formula industry executives and sales personnel, and food store owners; (b) how to strengthen Code implementation through clauses in free trade agreements; and (c) how to empower individuals by leveraging the influence of social networks and marketing. Other case studies can shed light on best practices for Code legislation and implementation in various regions. Impact studies that help law makers and advocates understand the immediate and long‐term impacts of policy changes will serve as important guides for prioritization and decision‐making in the future. The impact of the Code in combination with other essential breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support strategies must be understood if countries are to improve breastfeeding behaviours.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

HR, GB, and RPE conceived the idea for this research. HR conducted secondary data analysis, conducted all interviews, and led the writing of the final manuscript. HR, GB, and RPE. coded and analysed all interviews. LC, GB, and RPE. provided critical feedback to the manuscript and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Summary of case countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the key informants who participated in this research.

APPENDIX A.

Interview guide

-

1

Can you please tell me about our current role(s) at XXX and your background? (Probes: How long have you been working with the Code and in infant nutrition? How long have you been working in this region?)

-

2

In your experience, do you think that countries that have better Code implementation have higher EBF rates? Why or why not? Please provide specific examples if possible.

Possible probing questions if topics not mentioned:

-

3Legislation and policies: How important do you think legislating the Code is?

- (Probes: Is Code legislation always enforced? Can you describe how different countries have approached enforcing the Code? What other policies and legislation affect EBF or breastfeeding behaviour more generally? Why does successful enforcement of the Code appear to have different consequences within this region?)

-

4

Political will: From your perspective, have policymakers committed to the legislation and enforcement of the Code? (Probes: How could political will toward the Code be improved?)

-

5

Advocacy: How could advocates of breastfeeding work to advance the implementation and enforcement of the Code? What is the role of advocacy in the Code implementation? What could the role of advocacy be? (Probes: What about formula sales?)

-

6

Training and programme delivery: What role should health professionals' in‐service or pre‐service training play regarding the Code? How, if at all, does this training, or lack thereof, affect the Code implementation?

-

7

Coordination, goals, and monitoring: What are the barriers and facilitators to the coordination of the Code's implementation? (Probes: How are violations of the Code handled? How should they be handled? What barriers exist in this region to successful enforcement of the Code? How is the Code monitored? What organizations or bodies are responsible for the monitoring of the Code?)

-

8

Research and evaluation: What is the state of the research in this area? Based on your knowledge, what would be the pathways in which the Code impacts breastfeeding? Formula sales?

-

9

Is there anything else that you would like to mention in relation to this topic? Thank you for your time.

Robinson H, Buccini G, Curry L, Perez‐Escamilla R. The World Health Organization Code and exclusive breastfeeding in China, India, and Vietnam. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12685 10.1111/mcn.12685

REFERENCES

- Alive & Thrive . (2012). Legislation to protect breastfeeding in Viet Nam: A stronger decree 21 can improve child nutrition and reduce stunting.

- Almroth, S. , Arts, M. , Quang, N. D. , Hoa, P. T. , & Williams, C. (2008). Exclusive breastfeeding in Vietnam: An attainable goal. Acta Paediatrica, 97(8), 1066–1069. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P. , Smith, J. , Salmon, L. , Friel, S. , Kent, G. , Iellamo, A. , … Renfrew, M. J. (2016). Global trends and patterns of commercial milk‐based formula sales: Is an unprecedented infant and young child feeding transition underway? Public Health Nutrition, 19(14), 2540–2550. 10.1017/S1368980016001117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barennes, H. , Slesak, G. , Goyet, S. , Aaron, P. , & Srour, L. M. (2016). Enforcing the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes for better promotion of exclusive breastfeeding: Can lessons be learned? Journal of Human Lactation, 32(1), 20–27. 10.1177/0890334415607816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boza Martínez, S. , Guerrero, M. , Barreda, R. , & Espinoza, M. (2017). Recent changes in food labelling regulations in Latin America: The cases of Chile and Peru.

- Bradley, E. H. , Curry, L. A. , & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1758–1772. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J. P. (2012). Marketing breast milk substitutes: Problems and perils throughout the world. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 97(6), 529–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing Markets Foundation . (2017). Milking it: How milk formula companies are putting profits before science.

- Cheung, R . (2018). International comparisons of health and wellbeing in early childhood. Retrieved from https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2018-03/1521029143_annex-child-health-international-comparisons.pdf

- Coutsoudis, A. , Coovadia, H. M. , & King, J. (2009). The breastmilk brand: Promotion of child survival in the face of formula‐milk marketing. The Lancet, 374(9687), 423–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong, D. V. , Lee, A. H. , & Binns, C. W. (2005). Determinants of breast‐feeding within the first 6 months post‐partum in rural Vietnam. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 41(7), 338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International . (2015). Global infant formula data file: Data compiled by Euromonitor for WHO.

- Evans, A. (2018). Food for thought: An independent assessment of the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes.

- Glaser, B. G. , Strauss, A. L. , & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing Research, 17(4), 364. [Google Scholar]

- Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , Zehner, E. , Stahlhofer, M. , Lutter, C. , Clark, D. , Sterken, E. , … Ransom, E. I. (2017). New World Health Organization guidance helps protect breastfeeding as a human right. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A. , Dai, Y. , Xie, X. , & Chen, L. (2014). Implementation of international code of marketing breast‐milk substitutes in China. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(9), 467–472. 10.1089/bfm.2014.0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, M. (1996). Breastfeeding in Vietnam: Poverty, tradition, and economic transition. Journal of Human Lactation, 12(2), 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China . (2017). Order No. 17: National health and family planning Commission's decree on deciding to repeal the regulations on the sale of substitutes for breast milk substitutes

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Curry, L. , Minhas, D. , Taylor, L. , & Bradley, E. (2012). Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low‐and middle‐income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Advances in Nutrition, 3(6), 790–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , & Hall Moran, V. (2016). Scaling up breastfeeding programmes in a complex adaptive world. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(3), 375–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Lutter, C. K. , Rabadan‐Diehl, C. , Rubinstein, A. , Calvillo, A. , Corvalán, C. , … Ewart‐Pierce, E. (2017). Prevention of childhood obesity and food policies in Latin America: From research to practice. Obesity Reviews, 18(S2), 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz, E. G. , & Huffman, S. L. (2015). The impact of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes on WHO‐recommended breastfeeding practices. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36(4), 373–386. 10.1177/0379572115602174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries, A. M. , Huffman, S. L. , Mengkheang, K. , Kroeun, H. , Champeny, M. , Roberts, M. , & Zehner, E. (2016). Pervasive promotion of breastmilk substitutes in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and high usage by mothers for infant and young child feeding. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(S2), 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Victora, C. G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387(10017), 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children Fund . (2018). Don't push it: Why the milk formula industry must clean up its act. Retrieved from https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/content/dam/gb/reports/health/dont-push-it.pdf

- Small, M. L. (2011). How to conduct a mixed methods study: Recent trends in a rapidly growing literature. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L. , Lee, A. H. , Binns, C. W. , Yang, Y. , Wu, Y. , Li, Y. , & Qiu, L. (2014). Widespread usage of infant formula in China: A major public health problem. Birth, 41(4), 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (2017). Global breastfeeding scorecard.

- United Nations Children's Fund, Division of Data Research and Policy . (2018). Global UNICEF global databases: Infant and young child feeding: Exclusive breastfeeding, predominant breastfeeding, New York, January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinje, K. H. , Phan, L. T. H. , Nguyen, T. T. , Henjum, S. , Ribe, L. O. , & Mathisen, R. (2017). Media audit reveals inappropriate promotion of products under the scope of the International Code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes in South‐East Asia. Public Health Nutrition, 20(8), 1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D. , Horton, S. , Siregar, A. Y. M. , Pitriyan, P. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Mathisen, R. , … Rudert, C. (2016). The cost of not breastfeeding in Southeast Asia. Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), 1107–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WBTi . (2013). People's Republic of China. Retrieved from http://www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/GenerateReports/report/WBTi_China_2013.pdf

- WBTi . (2015a). Arrested development: All is not well with our children's health: 4th assessment of India's policies and programmes on infant and young child feeding.

- WBTi . (2015b). Vietnam assessment report. Retrieved from http://www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/GenerateReports/report/WBTi-Vietnam-2015.pdf

- WHO , UNICEF , IBFAN . (2016). Marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: National implementation of the international code status report 2016.

- World Bank . (2018). Data: World Bank country and lending groups.

- World Health Organization . (1981). International Code of marketing of breastmilk substitutes. [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization . (2003). Infant and young child feeding: A tool for assessing national practices, policies, and programmes.

- World Health Organization . (2017). The NetCode monitoring and assessment toolkit: Protocol for ongoing monitoring systems.

- World Health Organization . (2018). Protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services: The revised Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative 2018. [PubMed]

- Xu, F. , Qiu, L. , Binns, C. W. , & Liu, X. (2009). Breastfeeding in China: A review. International Breastfeeding Journal, 4(1), 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Summary of case countries.