Abstract

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disorder characterised by recurrent swellings involving subcutaneous and submucosal tissue that can be potentially life threatening in cases involving the upper airway. In this case report, we present a Syrian refugee family with HAE who have lived in Denmark since 2014. The index patient is an 8-year-old girl diagnosed with HAE after being hospitalised in Denmark with an angioedema attack. Her younger sister and father were diagnosed later, following investigation of the family. Exploring the family history, deaths due to suffocation were described in previous generations and other family members based in Sweden, Germany, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, USA and Syria could also potentially be affected. This highlights the need for a cross-border effort to diagnose and treat this inherited disorder.

Keywords: dermatology, ethics, ethnic studies

Background

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterised by recurrent swellings of the subcutaneous and/or submucosal tissue, which are caused by extensive bradykinin release as a result of deficiency, or impaired function of complement C1-inhibitor (C1-INH). When suspicion of HAE is raised, the diagnosis can often be confirmed by reduced C1-INH concentration and function and/or genetic testing.1 2

The disease is potentially life threatening when swelling results in laryngeal oedema and acute airway obstruction.3 4

Clinically, HAE is an extremely heterogeneous disease with an unpredictable pattern. The attack frequency varies considerably between patients, with attacks ranging from hardly ever to weekly in occurrence. Symptoms of HAE often occur in childhood and may persist throughout life.3 5 6

Many adult patients with HAE have impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) due to severely painful and disabling attacks.7–11 Results on paediatric HRQoL are more diverse.12 13

The described heterogeneity, as well as a lack of awareness of the disease among healthcare professionals, makes diagnosis and correct treatment challenging. It is a further challenge to treat patients of ethnic minorities due to possible language barriers and factors such as differences in culture, altered disease awareness and potential social factors (eg, low income).14 15 The Migrant Health Clinic, Odense University Hospital, has concluded ‘that refugees and migrants receive inequality in treatment compared to ethnical Danish patients to an extent that goes beyond patient safety and delays diagnosis, increases medication mistakes and leads to side effects and complications’.16 17 The need for extra consultation time, the presence of a translator and further education among health professionals was also emphasised to avoid this inequality in treatment.16 18 Immigrants, refugees and their descendants comprise 12% of Denmark’s population.19 The national HAE Centre in Denmark has experienced an increase in patients with HAE with foreign origin from 3 families (out of 31 HAE families) in 2014 to 9 families (out of 41 HAE families) in 2018, many of whom have relatives living in other countries. To date, no study has shown any significant change in the frequency of HAE worldwide; however, very few extensive prevalence studies have been performed.3 20

This report presents a Syrian refugee family with HAE and their challenges regarding HAE. The situation was further explored during an in-home visit after their first two consultations at the national HAE Centre.

Case presentation

The index patient is an 8-year-old girl from Syria who has been in Denmark since 2014. She had her first HAE-related hospitalisation in Denmark in 2017, where she arrived at the paediatric ward with swellings of her hands and feet accompanied with vomiting. A suspicion of HAE was raised, and biochemical testing revealed a low complement C4 of 0.06 g/L (0.1–0.4 g/L). Subsequently, a diagnosis of HAE (type I) was suggested based on a low C1-INH result of 0.10 g/L (0.21–0.39 g/L) and a low functional value of 0.16 (0.70–1.30; table 1). The national HAE Centre was contacted and the diagnosis was confirmed by molecular genetic diagnostics, showing a possible pathogenic variant in the SERPING1 gene (c.[51+5G>T];[=]). This variant is not previously described. The in silico tool Human Splicefinder predicts that (c.[51+5G>T];[=]) can affect the splicing of mRNA.

Table 1.

Biochemical testing

| Patient | C4 g/L (0.1–0.4) | C1-INH protein g/L (0.21–0.39) | C1-INH function (0.70–1.30) |

| Index patient | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Father | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.41 |

| Sister | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.5 |

C1-INH, C1-inhibitor.

A similar mutation c.51+5G>A has been described earlier in patients with HAE.

According to her mother, the patient had suffered from recurrent swelling attacks affecting her hands, feet and face since the age of 6 months, along with painful abdominal attacks. She had been admitted to hospitals in Syria with severe facial swelling and upper airway oedema. As far as it could be clarified, she had been treated with antihistamines, antibiotics and corticosteroids without benefit. The swelling attacks always resolved after a few days.

The father and the younger sisters’ complement profiles were also in accordance with HAE type I according to the guidelines.2 21 Genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis as the father and the younger sister had the same SERPING1 mutation.

Diagnosis is generally established through measurement of C1INH concentration and function.

The younger sister was asymptomatic to date, while the father described relapsing episodes of abdominal pain since the age of 19. The family received icatibant (a bradykinin B2-receptor antagonist) and Berinert (a plasma-derived C1-INH concentrate) for treatment of acute attacks at home and in the local emergency room (ER). Based on unfortunate experiences with treatment in Syria, the index patient had become afraid of needles, which made medical treatment challenging.

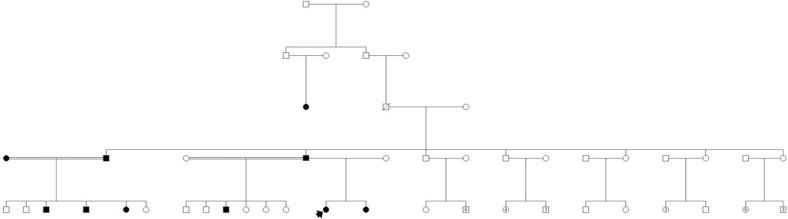

The father reported that he had six children, with his cousin in the USA and siblings in Sweden, Germany, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Syria (figure 1). He knew that several distant relatives in Syria had died at a young age due to swelling of the upper airway. The family was referred to the Department of Clinical Genetics, and a pedigree was drawn. Potentially affected relatives were discussed. The geneticist handed the father a letter, written in English, which explained the disease and inheritance pattern and which could be distributed to relatives living abroad. The family also received a general information folder explaining autosomal dominant inheritance in Arabic. The father was encouraged to inform all his relatives about the hereditary disease, which can be treated not only with expensive parenteral drugs, but possibly with oral danazol or the less effective tranexamic acid, which may be useful in high doses. Furthermore, several clinical trials are ongoing worldwide with newly developed drugs. The father used social media (Facebook) to contact his relatives and got contact with several distant family members who also experienced unusual swellings. He was informed that one of his sons in the USA and relatives living in Sweden had been tested and were receiving relevant therapy.

Figure 1.

Pedigree. Index patient marked with arrow.

As the family lived almost 400 km from the HAE Centre and did not have a car or confidence in public transportation, they had difficulty attending the outpatient clinic at the HAE Centre. It was therefore decided to visit the family in their private home to make sure that the family history was sufficiently explored and that they had sufficient knowledge about disease manifestations and treatment possibilities, as well as the logistics to treat acute attacks. It was revealed that the family had not used any of the prescribed medication since the diagnosis although the index child had experienced several HAE attacks. The parents explained that they had treated the peripheral swellings and painful abdominal attacks with paracetamol and chamomile tea. Although they received the medication free of charge from the HAE Centre, they were aware of the high cost of prescriptions and thought that the attacks were not severe enough to deserve such expensive medication. It is also possible that the anxiety about needles might have contributed to their decision. They had attended the local ER once, where the local staff seemingly decided not to treat the patient due to the high cost of the medication.

It was arranged that a representative from the Patient Association met the family at an outpatient visit to the HAE Centre. The representative, being a patient with HAE with HAE-affected children, told the family about the daily challenges and potential solutions of living with a rare disease causing acute, potentially life-threatening attacks. The representative also told the family about the patient association, which is now a Nordic Association (http://haescan.org/). While the family is not yet a member of the organisation, it is hoped that they may benefit for joining in the future.

Global health problem list

The family investigation of a hereditary disease is challenging when relatives are living abroad.

Recognising deceased patients and affected family members in developing countries may raise ethical issues and concerns with regard to availability of medications. What is the responsibility of the physician with regard to reaching out to distant relatives with a potentially life-threatening inherited disease?

Healthcare professionals may not be sufficiently aware of the rising cultural diversity in patients.

Translators may not always be available in emergency situations.

Global health problem analysis

As a result of rising immigration, Denmark is becoming a culturally diverse place. The number of patients with HAE in Denmark with a foreign background has increased markedly (2014–2018: three families to nine families). Patients often come to Denmark without a diagnosis, even though they have experienced swelling attacks and hospitalisations in their home country. Treating this life-long, potentially life threatening, genetic disease is in itself a challenge. The scope for treating non-Caucasian ethnic minorities, with a different culture and disease awareness, as well as a significant language barrier, makes it even more challenging. Non-Caucasian ethnic minorities generally have less access to healthcare services due to language barriers, impaired understanding of the healthcare system and health literacy, and psychosocial challenges that may be related to post-traumatic stress disorder (table 2).14–16 22–25 Ethnic minorities may also be more reluctant to accept support in the form of the HAE-App and participation in events via the HAE Patient Association. It is important that the patient association accommodates immigrants and refugees with this disease.

Table 2.

Challenges and solutions when treating ethnic minorities

| Challenges when treating ethnic minorities in the clinic | Solutions |

| Language barrier: poor communication14–17 22 | Professional interpreter available,15 extra consultation time |

| Cultural barrier14 16: differences between healthcare professionals and patients in relation to procedures, patterns of communication and roles. Ethnic barrier14 16 23: healthcare professionals’ negative bias towards ethnic minorities and stereotypical ideas about ethnic minorities |

Better education of healthcare professionals towards religion, values, actions, habits and traditions of ethnic minorities, as a foundation for a better physician–patient relationship and better compliance18 23 24 26 |

| Health literacy: level of knowledge about illness and the way healthcare services are organised. Conflicting concept of the doctor’s role14 16 | Better information and an on-call hotline for questions16 |

| More frequent psychosocial challenges25 | Multidisciplinary teams16 |

Educating healthcare professionals in cultural diversity and understanding are crucial to ensure correct care and treatment.18 26 The national HAE Centre serves 21 patients with HAE (2019) of foreign origin, from Germany, Norway, Portugal, Hungary, Turkey, Syria and Pakistan, and this reflects rising cultural diversity, even in a small country with 5.8 million inhabitants. In the reported family, only the children were Danish speaking, and therefore a skilful Arabic-speaking translator was needed for consultations. The use of family members or friends as translators is not recommended, due to the risk of misdiagnosis and misinterpretation and because it can be unethical to let a family member or a friend know more intimate disease details.19 As an alternative to translators attending the hospital, video interpretation is often used.19 Migration might cause change in the distribution of rare diseases and medical issues can influence this, as movement of patients across borders is on a rise, and worth to be attentive to as a physician.27

The reluctance of the index case to undergo treatment was alarming, as she suffered from frequent and severe external swellings, which were incapacitating, and also from very painful abdominal attacks with vomiting. Although an Arabic-speaking translator was used, the cultural difference and language barrier challenged the consultations. Even though the serious nature of this disease was explained and the importance of treatment highlighted, the family did not treat the attacks in the beginning. Only after an in-home visit, with an Arabic video interpreter using a tablet, did the family have more trust and faith in the recommendations from the Danish healthcare professionals. At the in-home visit, the family history was explored and we ensured that the family knew how to deal with acute attacks. The family’s personal challenges and barriers were uncovered, not only relating to the rare disease and its expensive therapy, but also with regard to their psychosocial resources. The family expressed joy and gratitude for the visit, and it provided a great deal of useful information about how this family is best managed. One of the main goals of this in-home visit was to support the family in home therapy. The importance of proper treatment of upper airway swellings was emphasised and the medication was demonstrated. The father was also encouraged to treat his abdominal attacks.

The cost of medication can challenge therapy, and this is not necessarily related to ethnicity. Otani et al also reported this as a problem in a group of 39 American patients with HAE, where 6 patients with HAE did not receive the targeted treatment.28

An international World Allergy Organisation guideline on HAE has been published, which mentions HAE as a serious global health problem.2 The guideline can be used to assist in rational decisions in the management of HAE, despite available therapies for HAE patients being limited in certain areas of the world. The guideline encourages the use of recommended therapies for all patients worldwide. Also, the necessity for family screening is emphasised as a delay in diagnosis and lack of appropriate therapy leads to morbidity, potential fatality and decreased quality of life. However, it is a challenge to complete family screening when family members are living in other countries, particularly in developing countries. Complement analyses may be especially challenging in developing countries, but blood or saliva samples could be sent abroad to developed countries for molecular genetic analysis, though cross-border genetic testing have some challenges with regard to, financial issues, quality of material and communication.29

The use of the World Wide Web and mobile phones has facilitated the contact between people all over the world. During the in-home visit, the mother of the family made contact with relatives in Syria. As reported, the father contacted distant relatives using Facebook. The story of distant relatives that died of HAE is not unique. When a physician confirms the diagnosis of a potentially life-threatening inherited disease, where does the responsibility lie for contacting relatives in other countries and how should it be done? It could become mandatory for the HAE Comprehensive Care Centres to assist in, and pay for, the practical follow-up of family investigation, in collaboration with the family.

A collaboration with the international HAE association (HAEi available at https://haei.org/), involving 74 member countries, could assist in establishing a useful network and facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of affected family members abroad. The recently established Global HAE Registry, which is an online platform collecting data on the natural history of patients with HAE, could also facilitate cross-country collaboration between physicians and patients.30

With regard to therapy, a global access programme has made recombinant C1-INH concentrate available in parts of the world where donation of medication is allowed, if the drug is not commercially available. Also, the usage of danazol may save lives of patients with HAE in developing countries.

Patient’s perspective.

The following was said by the father of the described family (translated to English):

“My general practitioner does not talk about the disease, she does not even mention it. Also the local hospitals don’t know hereditary angioedema. That’s the reason why I want to move closer to the national HAE Centre, where my children and myself can receive better care.

I have some mental problems and feel fatigue due to HAE. When I realized I had this disease, I feared that I would never get married.

My brother and his children were diagnosed with HAE when they came to Sweden as refugees. In Syria the physicians could not diagnose HAE. I saw the children with swollen faces and asked: “what is this”, but they couldn’t give a sufficient answer. The physicians in Syria thought it was an insect bite or other kinds of allergy.”

Learning points.

Culture and psychosocial challenges should be taken into account when consulting ethnic minorities.

Professional translators, possibly video interpretations, should be used for consultations when there is a language barrier

Extra consultation time may be needed in order to give and receive the correct information. An initial in-home visit can be a good idea.

Expertise centres are recommended to actively engage in cross-border family investigation of serious inherited diseases like hereditary angioedema.

International patient associations can support and participate in the diagnosis of treatment of patients abroad.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Marianne Antonius Jakobsen for molecular genetic diagnostics and Katja Venborg Pedersen for genetic guidance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All four authors have been at the in-home visit with the patients. ATHB has written the article drafts, while TMS and MS have supported and contributed the process. AB is the supervisor and the physician who is responsible for diagnosing and treating the patients.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: ATHB has been involved in teaching activities with CSL Behring. AB has been involved in research and teaching activities with CSL Behring, Shire and Biocryst. MS has received travel grants from CSL Behring.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bork K, Wulff K, Rossmann H, et al. Hereditary angioedema cosegregating with a novel kininogen 1 gene mutation changing the N-terminal cleavage site of bradykinin. Allergy 2019;74:2479–81. 10.1111/all.13869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurer M, Magerl M, Ansotegui I, et al. The International WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema-The 2017 revision and update. Allergy 2018;73:1575–96. 10.1111/all.13384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2008;359:1027–36. 10.1056/NEJMcp0803977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bork K, Hardt J, Witzke G. Fatal laryngeal attacks and mortality in hereditary angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:692–7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, et al. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med 2006;119:267–74. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bygum A. Hereditary and acquired angioedema in Denmark. Forum for Nordic Dermato-Venereology 2014;17:1–73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordenfelt P, Nilsson M, Lindfors A, et al. Health-Related quality of life in relation to disease activity in adults with hereditary angioedema in Sweden. Allergy Asthma Proc 2017;38:447–55. 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caballero T, Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, et al. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: results from the burden of illness study in Europe. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014;35:47–53. 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bygum A, Aygören-Pürsün E, Beusterien K, et al. Burden of illness in hereditary angioedema: a conceptual model. Acta Derm Venereol 2015;95:706–10. 10.2340/00015555-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, Beusterien K, et al. Estimation of EuroQol 5-Dimensions health status utility values in hereditary angioedema. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1699–707. 10.2147/PPA.S100383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansen SC, Bygum A, Banerji A, et al. Before and after, the impact of available on-demand treatment for Hae. Allergy Asthma Proc 2015;36:145–50. 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aabom A, Nguyen D, Fisker N, et al. Health-Related quality of life in Danish children with hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc 2017;38:440–6. 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel-Yeger B, Farkas H, Kivity S, et al. Health-Related quality of life among children with hereditary angioedema. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017;28:370–6. 10.1111/pai.12712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norredam ML, Nielsen AS, Krasnik A. Migrants' access to healthcare. Dan Med Bull 2007;54:48–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Rrustemi I, et al. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:503–12. ‐. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00376-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sodemann M, Kristensen TR, Nielsen D, et al. Experiences from migrant health clinic 2008-2013. Available: http://www.ouh.dk/dwn322207 [Accessed 07 May 2019].

- 17.Mladovsky P. Migration and health in the EU, research note for the European Commission. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/social_situation/docs/rn_migration_health.pdf

- 18.Sorensen J, Norredam M, Suurmond J, et al. Need for ensuring cultural competence in medical programmes of European universities. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:21. 10.1186/s12909-018-1449-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mottelson IN, Sodemann M, Nielsen DS. Attitudes to and implementation of video interpretation in a Danish Hospital: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health 2018;46:244–51. 10.1177/1403494817706200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aygören-Pürsün E, Magerl M, Maetzel A, et al. Epidemiology of Bradykinin-mediated angioedema: a systematic investigation of epidemiological studies. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018;13:73. 10.1186/s13023-018-0815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicardi M, Aberer W, Banerji A, et al. Classification, diagnosis, and approach to treatment for angioedema: consensus report from the hereditary angioedema international Working group. Allergy 2014;69:602–16. 10.1111/all.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abebe DS. Public health challenges of immigrants in Norway: NAKMI report 2/2010. Available: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2010/public-health-challenges-of-immigrants-in-norway-nakmireport-2-2010.pdf [Accessed 24 Nov 2019].

- 23.Commitee on Understanding and eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health care Smedley BD, Stith AY and Nelson Ar (EDS). unequal treatment. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brach C, Fraser I, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev 2000;57:181–217. 10.1177/1077558700057001S09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abebe DS, Lien L, Hjelde KH. What we know and don't know about mental health problems among immigrants in Norway. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:60–7. 10.1007/s10903-012-9745-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martimianakis MAT, Hafferty FW. The world as the new local clinic: a critical analysis of three discourses of global medical competency. Soc Sci Med 2013;87:31–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helble M. The movement of patients across borders: challenges and opportunities for public health. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:68–72. 10.2471/BLT.10.076612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otani IM, Christiansen SC, Busse P, et al. Emergency department management of hereditary angioedema attacks: patient perspectives. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:128–34. 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pohjola P, Hedley V, Bushby K, et al. Challenges raised by Cross-border testing of rare diseases in the European Union. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24:1547–52. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cicardi M. HAE global registry Foundation. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03828279 [Accessed 03 Feb 2020].