Abstract

Pneumocystis jirovecii is a common cause of pneumonia in patients with advanced HIV. In a lot of cases, there is a concomitant pulmonary infection. Cryptococcosis presents as a common complication for people with advanced HIV. However, it usually presents as meningitis rather than pneumonia. We present a case of a patient with coinfection by P. jirovecii and Cryptococcus spp without neurological involvement and a single nodular pulmonary lesion.

Keywords: HIV / AIDS, pneumonia (infectious disease), cryptococcosis, Cryptococcus

Background

Patients with HIV can have multiple infections at the same time. Pulmonary infection due to Pneumocystis jirovecii is a classic presentation of patients with advanced HIV infection. Multiple coinfections have been reported in association with P. jirovecii. However, Cryptococcus spp lung infection has seldom been reported. We report a case of a Cryptococcus spp pulmonary infection presenting as a solitary lung cavitated nodule after completed resolution of a P. jirovecii pneumonia in a patient with recent HIV diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old Hispanic man without any relevant medical history presented with a productive cough and dyspnoea that had progressed from only during heavy exertion to mild to resting dyspnoea over the course of 4 weeks. He mentioned that he had nocturnal diaphoresis. He began treatment at home with amantadine, chlorphenamine and paracetamol without significant improvement.

At the initial evaluation, his breathing was laboured with the use of accessory muscles. Acrocyanosis and central cyanosis were observed. Fine rales with hypoventilation were heard on thoracic auscultation. The O2 saturation was at 64%–70% without supplemental oxygen. The respirations were 30/min, the heart rate was 110 beats/min and the blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. White plaques were seen in the pharynx and palate.

Investigations

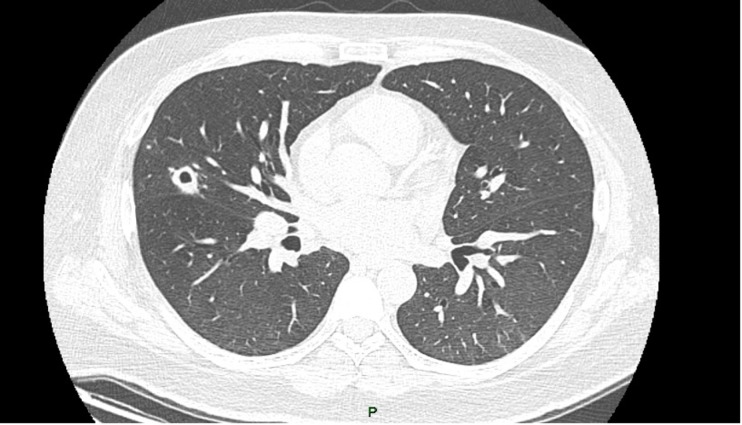

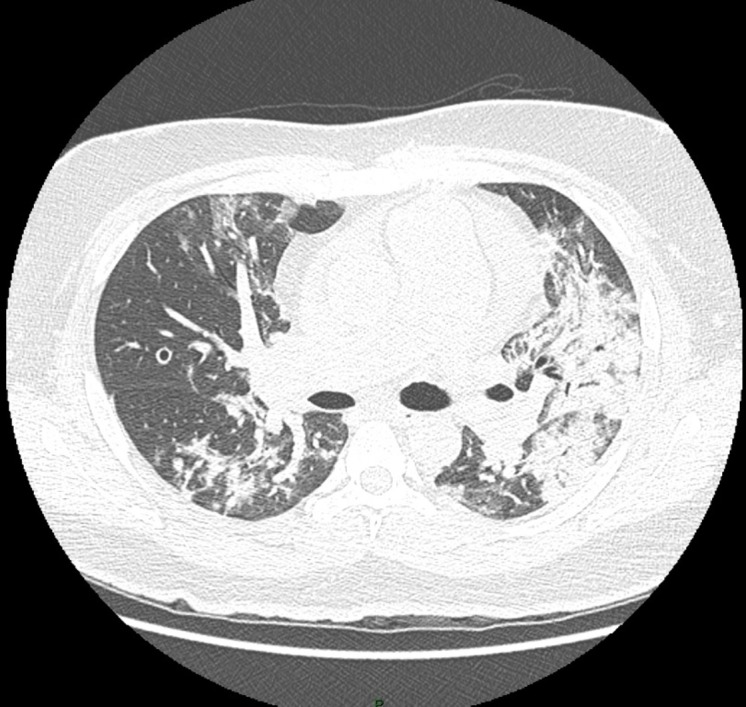

Bloodwork was ordered and a thoracic X-ray and CT scan were taken, which showed alveolar occupation on both hemithoraxes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Admission CT scan.

Giemsa staining was conducted on the sputum, and it showed cysts with P. jirovecii. Additionally, cultures for aerobes, mycobacterium and fungi were ordered and were all negative. The cryptococcal antigen was negative in the bloodwork and beta-D-glucan levels were >500 pg/mL.

An HIV test was ordered and the result was positive. The CD4 count was 4/µL and the viral count was 816 000 copies/mL.

Treatment

The patient was hospitalised in the intensive care unit, and treatment began with cotrimoxazol, prednisone, ceftriaxone, clarithromycin and caspofungin while the test results came back. After a diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed on the day after his hospitalisation, his condition deteriorated, resulting in intubation with mechanical ventilation.

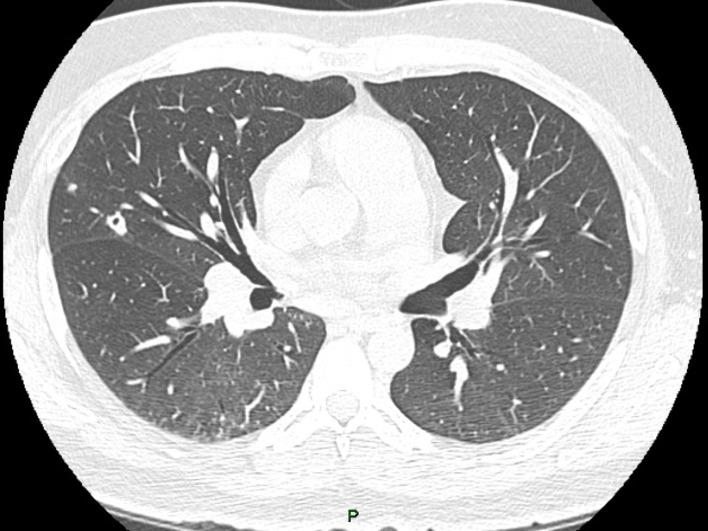

Infection by P. jirovecii was confirmed by pathology and PCR. The patient improved slowly, and by the 12th day, antiretroviral treatment was initialised (dolutegravir, emtricitabine and tenofovir). We took another chest CT scan on day 14 (figure 2) that showed improvement of the alveolar occupation. He was extubated on the 20th day and released on the 35th day.

Figure 2.

Chest CT scan on day 14 after admission.

Outcome and follow-up

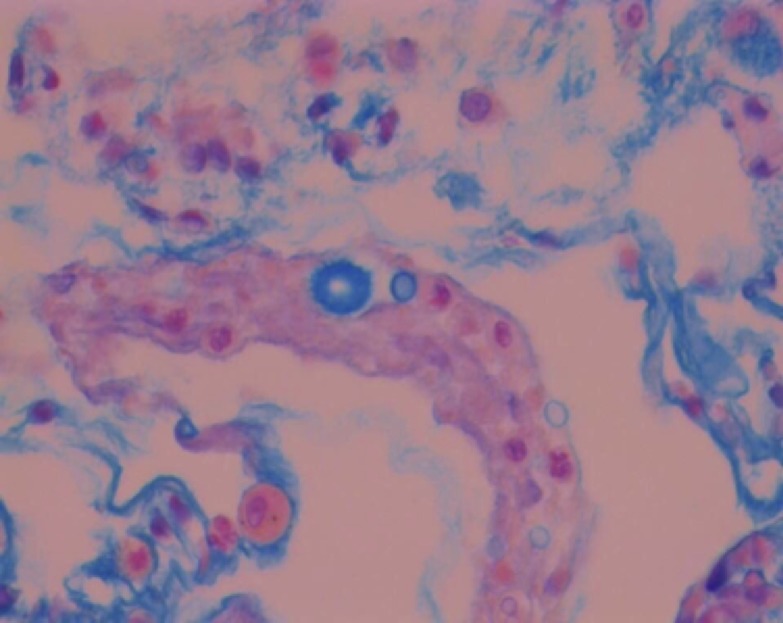

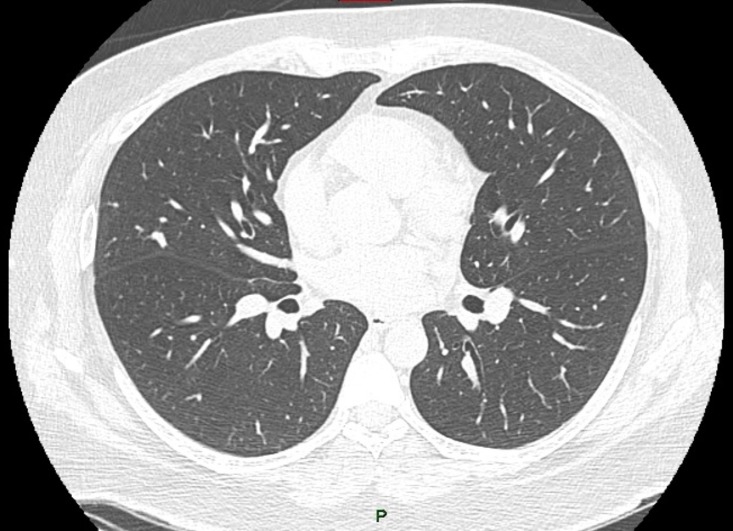

As part of his HIV follow-up, a thoracic X-ray was taken after 14 days of his discharge. It showed a cavitated nodule in the right middle lobe. So, a CT scan (figure 3), was conducted. It showed complete improvement of the alveolar occupation but a larger cavitated nodule. Consequently, another bronchoscopy was performed. Infection by Cryptococcus spp was confirmed by Masson’s trichrome stain (figure 4). The bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. In the bloodwork, the cryptococcal antigen became positive (1:640) and the beta-d-glucan was negative, so a lumbar puncture was performed in order to rule out meningitis. The histoplasmosis antigen was not found in the urine. At this point, the patient had 71 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA and the CD4 count was 88/µL. Because the patient was asymptomatic, 400 mg of fluconazole per day was indicated. The CT scan after 4 weeks showed a reduction in the size of the nodule (figure 5), the HIV-1 RNA was 72 copies/mL and the CD4 count was 155/µL. He continued with fluconazole to complete the 6 months treatment. After 36 weeks of the initial P. jirovecii pneumonia a new CT scan showed complete resolution of the cavitated lesion (figure 6).

Figure 3.

Chest CT scan on day 14 after discharge.

Figure 4.

Cryptococcus spp in bronchial brushing with Masson's trichrome staining.

Figure 5.

Chest CT scan on the 4th week of fluconazole treatment.

Figure 6.

Chest CT scan 36 weeks after the initial Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Discussion

P. jirovecii (previously Pneumocystis carinii) is a common cause of pneumonia in HIV severely immunocompromised patients. The incidence has decreased in developed countries due to the early diagnosis and treatment of HIV and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections.1 However, in low-income and middle-income countries, it continues to be one of the first manifestations of HIV.2 3

Conversely, cryptococcal pneumonia is rare, although it is believed to be underdiagnosed. In patients with HIV who are immunocompromised, cryptococcal meningitis is much more common. When pulmonary involvement is seen in immunocompromised patients, it is more commonly an infection by Cryptococcus neoformans (A serotype) than Cryptococcus gattii (D serotype), while C. gattii is the most common cause of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients.4

In patients with HIV, P. jirovecii coinfection with other pulmonary pathogens, such as bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, viruses and even parasites, has been reported. Coinfection rates with other micro-organisms range from 20% to 70%.5 An example of bacterial coinfection was presented by Mamoudou et al who reported two cases of patients with HIV and P. jirovecii coinfection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in which timely diagnosis and treatment for both conditions had a favourable outcome.6

Coinfection of P. jirovecii with Mycobacterium tuberculosis has also been reported in the literature.7 8 At present, it is recognised as the most common coinfection with P. jirovecii in patients with HIV.5 In a study published by Chiliza et al, they report that in their population of a referral hospital in South Africa, the coinfection rate was 23.6%. This coinfection was associated with a worse prognosis.9

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has been reported as a coinfection agent in multiple articles.10 11 The effect of this coinfection on the prognosis is controversial. Some studies indicate that there is no difference in morbidity and mortality between patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia with or without CMV coinfection,12 13 while others report higher mortality in patients with coinfection.14 Other viruses, such as influenza and adenovirus, have also been reported as coinfection agents.15 16

Strongyloides stercoralis has also been reported as a coinfection agent in a patient with HIV and Pneumocystis in Argentina. The patient also had C. neoformans meningoencephalitis and had a fatal outcome despite treatment.17

Coinfection by Pneumocystis and Histoplasma has previously been reported in the literature as a rare event.18 However, a recent study in Mexico highlighted the rate of coinfection between Pneumocystis and Histoplasma capsulatum in patients with HIV (10.7%). It found that this coinfection doubles the mortality rate of patients compared with those with only a single infection.19

Another fungus that has been rarely reported as causing pulmonary coinfection in patients with HIV and Pneumocystis is C. neoformans.20–22 This association has been reported in infections by other retroviruses as human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1).23

In this case report, we present a case of a young patient with advanced HIV who presented with a pneumonic infection due to P. jirovecii infection. After satisfactory treatment, cavitated nodules were discovered in the lungs that were diagnosed as pulmonary cryptococcosis.

In retrospect, the patient had a CT scan on the 15th day of hospitalisation and some cavitated nodules were seen. Taking into account that the material from the first bronchoscopy did not show any yeast and the serum Cryptococcus antigen was negative at admission, we assumed that these nodules were by P. jirovecii itself. Therefore, our case highlights the need to expand the differential diagnosis of pulmonary nodules that do not improve in radiographic follow-up, even in the context of previously negative tests such as cryptococcal antigen serum test.

Pulmonary cavitations due to P. jirovecii have been reported in the literature as a form of presentation in patients with advanced HIV.24 However, there are other infections that can be responsible for pulmonary cavitations in patients with HIV. The principal one is C. neoformans, although infections due to Penicillium marneffei, Aspergillus spp and M. tuberculosis should also be considered.25

These nodules were possibly made notable by improving the radiographic findings resulting from P. jirovecii infection, coupled with immune reconstitution syndrome, which helped so that the previously covert Cryptococcus spp infection could be discovered after the start of antiretroviral therapy.26 Our patient had multiple risk factors for developing immune reconstitution syndrome, such as low T-CD4 lymphocyte count, high viral load and initiation of therapy that included integrase inhibitors.27

Learning points.

Patients with advanced HIV can have multiple infections at the same time due to the advanced immunosuppression. This could increase the morbidity and mortality if these infections are not diagnosed and treated effectively.

Pneumocystis may not be the sole pathogen, but rather it may be a coinfection with other micro-organisms.

Cryptococcus lung infection, although uncommon, could be a cause of cavitary lung lesions.

A negative cryptococcal antigen test does not exclude Cryptococcus spp as a cause of lung cavitated nodules. Repeat testing can be valuable in cases of progression or lack of response to treatment even when a cause has been identified.

Footnotes

Contributors: BV-A and AT-E conceived the idea and design of the article. BV-A, JP-G and AT-E contributed to the preparation and review of the initial manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fei MW, Sant CA, Kim EJ, et al. Severity and outcomes of Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients newly diagnosed with HIV infection: an observational cohort study. Scand J Infect Dis 2009;41:672–8. 10.1080/00365540903051633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calderón EJ, de Armas Y, Panizo MM, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in Latin America. A public health problem? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2013;11:565–70. 10.1586/eri.13.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowe DM, Rangaka MX, Gordon F, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in tropical and low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-regression. PLoS One 2013;8:e69969. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2008;29:141–50. 10.1055/s-2008-1063853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisk DT, Meshnick S, Kazanjian PH. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients in the developing world who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:70–8. 10.1086/344951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamoudou S, Bellaud G, Ana C, et al. [Lung co-infection by Pneumocystis jirovecii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in AIDS: report of two cases]. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21:95. 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.95.5993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orlovic D, Kularatne R, Ferraz V, et al. Dual pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Pneumocystis carinii in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:289–94. 10.1086/318475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheikholeslami MF, Sadraei J, Farnia P, et al. Co-infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Pneumocystis jirovecii in the Iranian patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2015;8:e17254. 10.5812/jjm.17254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiliza N, Du Toit M, Wasserman S. Outcomes of HIV-associated Pneumocystis pneumonia at a South African referral hospital. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201733. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuganji E, Abe T, Kobayashi H, et al. Fatal pulmonary co-infection with Pneumocystis and cytomegalovirus in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Intern Med 2014;53:1575–8. 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polaczek MM, Zych J, Oniszh K, et al. [Pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-infected patients with cytomegalovirus co-infection. Two case reports and a literature review]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2014;82:458–66. 10.5603/PiAP.2014.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bozzette SA, Arcia J, Bartok AE, et al. Impact of Pneumocystis carinii and cytomegalovirus on the course and outcome of atypical pneumonia in advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Infect Dis 1992;165:93–8. 10.1093/infdis/165.1.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayner CE, Baughman RP, Linnemann CC, et al. The relationship between cytomegalovirus retrieved by bronchoalveolar lavage and mortality in patients with HIV. Chest 1995;107:735–40. 10.1378/chest.107.3.735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benfield TL, Helweg-Larsen J, Bang D, et al. Prognostic markers of short-term mortality in AIDS-associated Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest 2001;119:844–51. 10.1378/chest.119.3.844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Kampen JJA, Bielefeld-Buss AJ, Ott A, et al. Case report: oseltamivir-induced resistant pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in a patient with AIDS and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. J Med Virol 2013;85:941–3. 10.1002/jmv.23560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koopmann J, Dombrowski F, Rockstroh JK, et al. Fatal pneumonia in an AIDS patient coinfected with adenovirus and Pneumocystis carinii. Infection 2000;28:323–5. 10.1007/s150100070028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bava AJ, Romero M, Prieto R, et al. A case report of pulmonary coinfection of Strongyloides stercoralis and Pneumocystis jiroveci. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011;1:334–6. 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60056-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahab A, Chaudhary S, Khan M, et al. Concurrent Pneumocystis jirovecii and pulmonary histoplasmosis in an undiagnosed HIV patient. BMJ Case Rep 2018;48:bcr-2017-223422 2018 10.1136/bcr-2017-223422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carreto-Binaghi LE, Morales-Villarreal FR, García-de la Torre G, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum and Pneumocystis jirovecii coinfection in hospitalized HIV and non-HIV patients from a tertiary care hospital in Mexico. Int J Infect Dis 2019;86:65–72. 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javier B, Susana L, Santiago G, et al. Pulmonary coinfection by Pneumocystis jiroveci and Cryptococcus neoformans. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012;2:80–2. 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60195-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mootsikapun P, Chetchotisakd P, Intarapoka B. Pulmonary infections in HIV infected patients. J Med Assoc Thai 1996;79:477–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rey A, Losada C, Santillán J, et al. Comparación de infecciones por Pneumocystis jiroveci en pacientes con y sin diagnóstico de infección por VIH. Rev Chil infectología 2015;32:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai A, Fe A, Desai A, et al. A case of pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii and Cryptococcus neoformans in a patient with HTLV-1 associated adult T- cell leukemia/lymphoma: Occam's razor blunted. Conn Med 2016;80:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin C-Y, Sun H-Y, Chen M-Y, et al. Aetiology of cavitary lung lesions in patients with HIV infection. HIV Med 2009;10:191–8. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aviram G, Fishman JE, Sagar M. Cavitary lung disease in AIDS: etiologies and correlation with immune status. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2001;15:353–61. 10.1089/108729101750301906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang CC, Sheikh V, Sereti I, et al. Immune reconstitution disorders in patients with HIV infection: from pathogenesis to prevention and treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014;11:223–32. 10.1007/s11904-014-0213-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutertre M, Cuzin L, Demonchy E, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy containing integrase inhibitors increases the risk of iris requiring hospitalization. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:e23–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]