Abstract

This cohort study examines rates of vaping and smoking among youths aged 16 to 19 years in the United States, Canada, and England from 2017 to 2019.

There are concerns over increases in vaping among North American youths.1,2,3 In the US in 2019, one-fifth of 10th-grade students and one-quarter of 12th-grade students reported using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.2 The extent to which similar increases have been observed in countries with different regulatory environments, such as Canada and England, is an important question. In 2018, Canada loosened restrictions on the sale and marketing of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes, whereas e-cigarettes in England are subject to more comprehensive regulations than in either Canada or the US.

Methods

Repeated cross-sectional online surveys were conducted in July and August 2017, August and September 2018, and August and September 2019. National samples of youths aged 16 to 19 years in Canada (n = 12 018), England (n = 11 362), and the US (n = 12 110) were recruited through the Nielsen Consumer Insights Global Panel. Respondents (and their parents, if respondents were younger than 18 years) were provided with study information and asked to indicate consent in the online survey. The study was reviewed and received ethics clearance through a University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee and the King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing & Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee.

Self-reported e-cigarette use and cigarette-smoking measures were categorized into use within the past 30 days, the past week, and on at least 20 of the past 30 days. Poststratification sample weights were calculated for each country, based on age, sex, geographic region, and race/ethnicity (US only); furthermore, to ensure sample comparability across years, waves 2 (2018) and 3 (2019) were calibrated back to wave 1 (2017) levels for student status (student vs other) and school grades (not stated or <70%, 70%-79%, 80%-89%, or 90%-100%), and we used the National Youth Tobacco Survey in the US and Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs Survey in Canada to calibrate to the trend over time for smoking in the past 30 days.

A full description of the study methods is available elsewhere.4 Logistic regression models were estimated to examine changes between survey years, adjusting for sex, age group, and race/ethnicity. The P value threshold for significance was set to <.01, 2-tailed. Analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc).

Results

The prevalence of vaping increased between 2018 and 2019 within all 3 countries but was substantially more prevalent in Canada and the US compared with England (Table). Vaping was substantially higher among individuals who reported smoking than other respondents in all 3 countries, although increases between 2017 and 2019 were observed across all subgroups for most measures of vaping in the US and Canada including among those who reported never smoking (by weighted percentages; eg, in those who reported ever vaping: Canada: 2017, 13.5%; 2019, 24.5%; P < .001; US: 2017, 13.1%; 2019, 25.4%; P < .001), smoking experimentally (eg, in those who reported having vaped in the past 30 days: Canada: 2017, 18.2%; 2019, 37.6%; P < .001; US: 2017, 24.4%; 2019, 36.7%; P < .001), and currently smoking (eg, in those who reported vaping in the past week: Canada: 2017, 28.8%; 2019, 44.7%; P = .006; US: 2017, 36.3%; 2019, 54.7%; P = .002) (Table).

Table. Prevalence of Vaping, Overall and by Smoking Status, Among Youths Aged 16 to 19 Years From 2017 to 2019 by Country.

| Groupa | Study participants, weighted No. (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | England | US | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | P values between years | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | P values between years | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | P values between years | |

| Total sample, No. | 4038 | 3845 | 4135 | 3995 | 3874 | 3493 | 4095 | 4034 | 3981 | |||

| Ever vaped | 1182 (29.3) | 1275 (33.2) | 1680 (40.6) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d | 1348 (33.7) | 1283 (33.1) | 1260 (36.1) | .61b; .02c; .05d |

1283 (31.3) | 1336 (33.1) | 1734 (43.6) | .14b; <.001c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past 30 d | 340 (8.4) | 463 (12.1) | 738 (17.8) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d | 347 (8.7) | 351 (9.0) | 439 (12.6) | .59b; <.001c; <.001d |

454 (11.1) | 635 (15.7) | 736 (18.5) | <.001b; .006c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past week | 208 (5.2) | 290 (7.5) | 508 (12.3) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d | 184 (4.6) | 179 (4.6) | 241 (6.9) | .93b; <.001c; <.001d |

262 (6.4) | 416 (10.3) | 503 (12.6) | <.001b; .007c; <.001d |

| Used e-cigarettes ≥20 d in past 30 d | 74 (1.8) | 92 (2.4) | 236 (5.7) | .06b; <.001c; <.001d |

59 (1.5) | 76 (2.0) | 94 (2.7) | .14b; .08c; <.001d |

89 (2.2) | 154 (3.8) | 267 (6.7) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d |

| Never smoked | ||||||||||||

| Ever vaped | 373 (13.5) | 500 (18.8) | 697 (24.5) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d | 284 (11.9) | 277 (12.0) | 337 (15.6) | .93b; .002c; .001d |

363 (13.1) | 434 (15.9) | 672 (25.4) | .015b; <.001c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past 30 d | 63 (2.3) | 124 (4.7) | 195 (6.8) | <.001b; .003c; <.001d | 39 (1.6) | 40 (1.7) | 65 (3.0) | .88b; .014c; .005d |

66 (2.4) | 157 (5.8) | 196 (7.4) | <.001b; .04c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past week | 22 (0.8) | 68 (2.6) | 114 (4.0) | <.001b; .013c; <.001d | 12 (0.5) | 9 (0.4)e | 30 (1.4) | .68b; .008c; .005d |

31 (1.1) | 78 (2.9) | 116 (4.4) | <.001b; .013c; <.001d |

| Used e-cigarettes ≥20 d in past 30 d | 5 (0.2)e | 10 (0.4)e | 27 (1.0) | .13b; .05c; .001d |

4 (0.2)e | 2 (0.1)e | 6 (0.3)e | .46b; .18c; .38d |

11 (0.4) | 33 (1.2) | 49 (1.8) | .005b; . 14c; <.001d |

| Smoking experimentally | ||||||||||||

| Ever vaped | 594 (58.7) | 627 (62.9) | 765 (73.5) | .07b; <.001c; <.001d |

787 (61.2) | 748 (60.0) | 712 (65.9) | .51b; <.01c; .04d |

708 (65.5) | 733 (66.7) | 907 (77.9) | .53b; <.001c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past 30 d | 184 (18.2) | 261 (26.2) | 391 (37.6) | <.001b; <.001c; <.001d | 195 (15.2) | 200 (16.0) | 254 (23.6) | .64b; <.001c; <.001d |

264 (24.4) | 363 (33.1) | 427 (36.7) | <.001b; .14c; <.001d |

| Vaped in past week | 111 (11.0) | 163 (16.3) | 272 (26.1) | .001b; <.001c; <.001d | 97 (7.5) | 104 (8.3) | 127 (11.7) | .54b; .02c; .002d |

146 (13.5) | 247 (22.5) | 292 (25.1) | <.001b; .23c; <.001d |

| Used e-cigarettes ≥20 d in past 30 d | 36 (3.6) | 49 (4.9) | 137 (13.2) | .13b; <.001c; <.001d | 28 (2.1) | 42 (3.4) | 47 (4.3) | .11b; .36c; .01d |

43 (4.0) | 85 (7.8) | 163 (14.0) | .002b; <.001c; <.001d |

| Smoking currently | ||||||||||||

| Ever vaped | 156 (79.8) | 116 (76.7) | 148 (86.7) | .70b; .15c; .35d |

206 (86.7) | 228 (85.0) | 184 (84.9) | .76b; .93c; .69d |

155 (85.4) | 135 (81.3) | 111 (91.0) | .43b; .04c; .16d |

| Vaped in past 30 d | 68 (34.8) | 66 (43.7) | 103 (60.1) | .06b; .003c; <.001d |

85 (35.7) | 104 (38.9) | 107 (49.2) | .70b; .03c; .008d |

100 (55.2) | 94 (56.3) | 81 (66.0) | .89b; .12c; .07d |

| Vaped in past week | 56 (28.8) | 51 (33.8) | 76 (44.7) | .22b; .07c; .006d |

53 (22.2) | 61 (22.7) | 72 (33.1) | .94b; .02c; .02d |

66 (36.3) | 76 (45.7) | 67 (54.7) | .12b; .20c; .002d |

| Used e-cigarettes ≥20 d in past 30 d | 27 (13.8) | 26 (17.0) | 42 (24.6) | .47b; .06c; .02d |

19 (8.0) | 31 (11.6) | 34 (15.6) | .20b; .32c; .03d |

25 (13.9) | 28 (17.0) | 30 (24.8) | .44b; .24c; .04d |

Those who reported formerly smoking were not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Comparison between 2017 and 2018 in prevalence of measure within group and country, from logistic regression models adjusting for sex, age group (16-17 years vs 18-19 years), and race/ethnicity (white vs other).

Comparison between 2018 and 2019 in prevalence of measure within country.

Comparison between 2017 and 2019 in prevalence of measure within country.

High variability; interpret with caution.

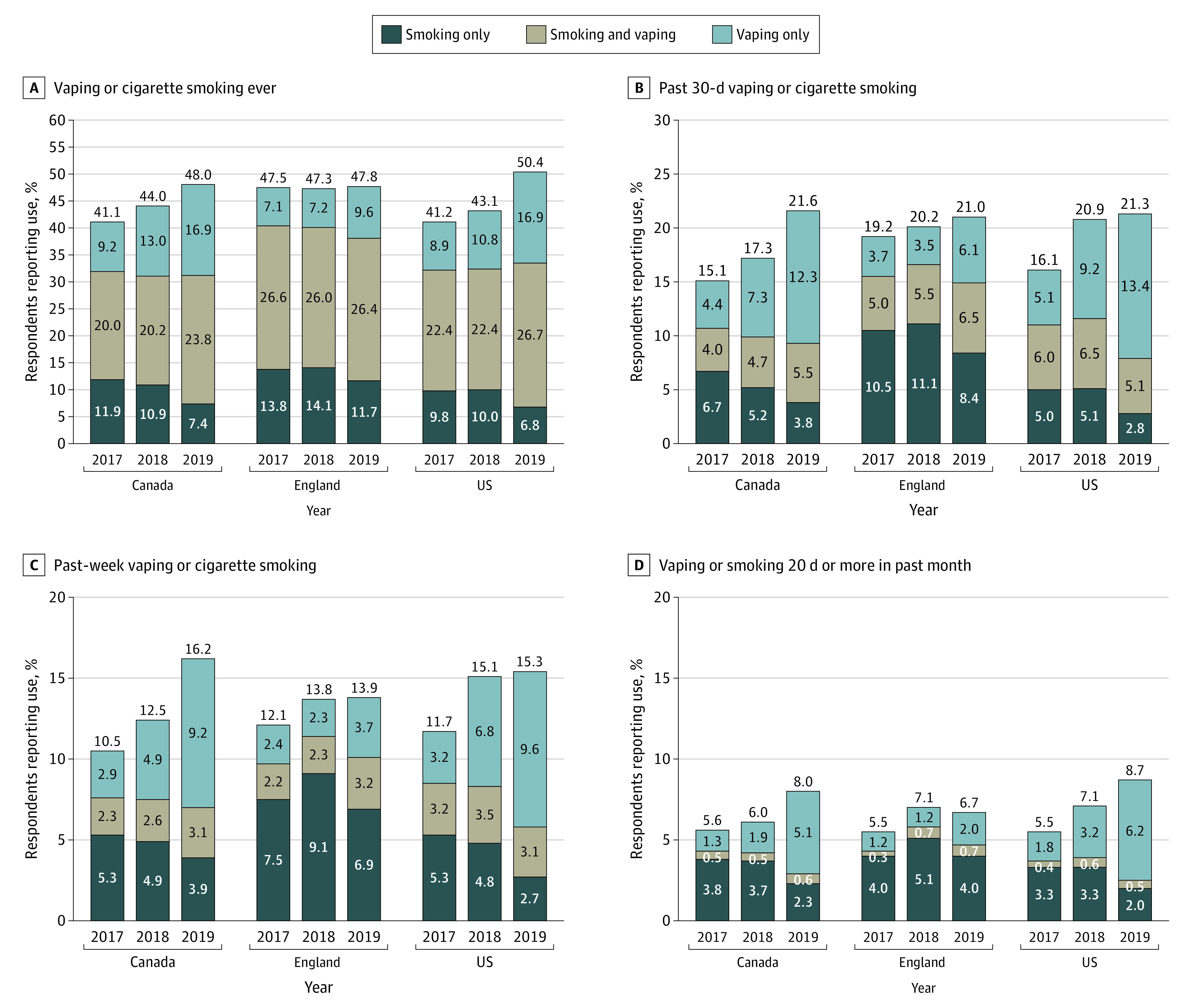

As the Figure indicates, the proportion of youths who ever vaped and/or smoked increased between 2017 and 2019 in Canada (from 41.1% to 48.0%; P < .001) and the US (from 41.2% to 50.4%; P < .001), but not in England. The same pattern was observed for vaping and/or smoking more recently and frequently, with significant increases between 2017 and 2019 in the US and Canada, but not in England, for use in the past 30 days (US: from 16.1% to 21.3%; Canada: from 15.1% to 21.6%), in the past week (US: from 11.7% to 15.3%; Canada: from 10.5% to 16.2%), and on 20 or more days in the past month (US: from 5.5% to 8.7%; Canada: from 5.6% to 8.0%) (P < .001 for all measures).

Figure. Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking, Vaping, and Dual Use Among Youths Aged 16 to 19 Years, 2017 to 2019, by Country.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate substantially greater increases in vaping among North American youths compared with England. The number of youths who vaped frequently (in the past week or more often) has at least doubled between 2017 and 2019 in Canada and the US. Although the prevalence of vaping was markedly higher among those who reported smoking currently, there are many more individuals who did not smoke in the population; therefore, youths who do not smoke accounted for a greater number of those who vaped regularly than youths who smoked in 2019. The increases in frequent vaping in the US and Canada are consistent with the increase since 2017 in the popularity of nicotine salt products, such as Juul, which have markedly higher nicotine concentrations compared with earlier generations of e-cigarettes.5 In England, e-cigarettes are subject to greater marketing restrictions and a maximum nicotine concentration of 20 mg/mL.

Study limitations include a nonprobability sample and potential biases associated with self-reported surveys. However, poststratification weights were used, and smoking prevalence estimates were weighted to national benchmark surveys in US and Canada.1,2,3,4

Overall, the findings depict substantial increases in the percentage of youths who vape in the US and Canada. Given that e-cigarette use among adults has decreased over the same period, the findings suggest the growth of the US and Canadian e-cigarette markets since 2017 may have been driven primarily by consumption by young people.6 The extent to which the lower vaping prevalence in England is associated with the different market and regulatory environment warrants close consideration.

References

- 1.Hammond D, Reid JL, Rynard VL, et al. Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: repeat national cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2019;365:l2219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017-2019. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1490-1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond D, Reid JL, White CM, Boudreau C ITC youth tobacco and e-cigarette survey: technical report—wave 1. Published 2017. Accessed December 3, 2018. http://davidhammond.ca/projects/e-cigarettes/itc-youth-tobacco-ecig/

- 5.Romberg AR, Miller Lo EJ, Cuccia AF, et al. Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013-2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;203:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai H, Leventhal AM. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA. 322 (18), 1824-1827. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.15331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]