This cross-sectional study examines the use and risks of proxy access to adult patient portals in independently operated and system-affiliated US hospitals.

Key Points

Question

Do hospitals allow caregivers to access patient portals in a manner that protects security and privacy?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 102 US hospitals, 68% of hospitals in the sample offered proxy accounts to caregivers of adult patients, 45% of the hospital personnel surveyed endorsed sharing of login credentials, and 19% of hospitals that provided proxy accounts enabled patients to limit the types of information seen by their caregivers.

Meaning

Findings of this study suggest that hospitals and electronic health record vendors should work together to improve the availability and setup of proxy accounts not only to facilitate caregiver access but also to protect the privacy and security of patient health information.

Abstract

Importance

Patient portals can help caregivers better manage care for patients, but how caregivers access the patient portal could threaten patient security and privacy.

Objective

To identify the proportions of hospitals that provide proxy accounts to caregivers of adult patients, endorse password sharing with caregivers, and enable patients to restrict the types of information seen by their caregivers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national cross-sectional study included a telephone survey and was conducted from May 21, 2018, to December 20, 2018. The randomly selected sample comprised 1 independent hospital and 1 health system–affiliated general medical hospital from every US state and the District of Columbia. Specialty hospitals and those that did not have a patient portal in place were excluded. An interviewer posing as the daughter of an older adult patient called each hospital to ask about the hospital’s patient portal practices. The interviewer used a structured questionnaire to obtain information on proxy account availability, password sharing, and patient control of their own information.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of hospitals that provided proxy accounts to caregivers of adult patients. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of hospitals with personnel who endorsed password sharing and the proportion that allowed adult patients to limit the types of information available to caregivers.

Results

After exclusions, a total of 102 (51 health system–affiliated and 51 independent) hospitals were included in the study. Of these hospitals, 69 (68%) provided proxy accounts to caregivers of adult patients and 26 (25%) did not. In 7 of 102 hospitals (7%), the surveyed personnel did not know if proxy accounts were available. In the 94 hospitals asked about password sharing between the patient and caregiver, personnel in 42 hospitals (45%) endorsed the practice. Among hospitals that provided proxy accounts, only 13 of the 69 hospitals (19%) offered controls that enabled patients to restrict the types of information their proxies could see.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that almost half of surveyed hospital personnel recommended password sharing and that few hospitals enabled patients to limit the types of information seen by those with proxy access. These findings suggest that hospitals and electronic health record (HER) vendors need to improve the availability and setup process of proxy accounts in a way that allows caregivers to care for patients without violating their privacy.

Introduction

According to an American Hospital Association survey, 95% of US hospitals have a patient portal, a web-based or smartphone application that lets patients access their medical data and perform other tasks such as scheduling appointments or requesting prescription refills.1 Patient portals may be particularly helpful for older adults who are prone to recurring health issues.2,3 However, older adults are often uncomfortable using patient portals because they lack technology access and have complex health issues that interfere with their ability to learn or use new systems.4,5,6

Approximately 40 million people in the United States serve as caregivers, defined as those who assist patients with health management and daily living tasks.7 Giving caregivers access to the patient portals of those they are helping can improve their care.8,9,10,11 In a 2011 survey, 79% of respondents wanted to be able to share access to their patient portal with their caregivers; in almost half of those cases, the caregiver did not live with the patient.12

Some hospitals allow patients to authorize access to their portal through a proxy account, which enables caregivers to log in with their own credentials. However, caregivers commonly access these portals using the patients’ portal credentials, either because proxy accounts are unavailable or because sharing credentials is viewed as the easier option.13,14 Sharing credentials can lead to multiple data security and privacy problems, including revealing more information than the patient intended, and to health care practitioner confusion and mistakes if they do not know with whom they are communicating.14,15

The proportion of hospitals that provide proxy access to patient portal accounts is unknown. One study reviewed the websites of 20 large health systems and found that 90% of hospitals allowed adult patients to authorize proxy accounts for their caregivers; however, only 3 different electronic health record (EHR) systems were represented in this sample.16 The present study was prompted by one of us encountering a hospital with no proxy access that suggested patients share their login credentials with caregivers to provide access to the patients’ information. We aimed to investigate the proportion of hospitals that did not provide proxy accounts, endorsed password sharing between users of the portal, or did not allow patients to limit the information seen by caregivers, thus unintentionally threatening patient privacy. We examined the availability, setup, and privacy limits of adult proxy accounts in randomly selected hospitals across the United States.

Methods

This cross-sectional study, involving a telephone interview, was conducted from May 21, 2018, to December 20, 2018. The study, which included the use of deception, was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived because institutions were considered the study participants and obtaining informed consent would likely lead to social desirability bias.

Hospital Identification

Approximately half of US physicians are employed by a hospital or medical group, and the percentage of independent physicians decreases yearly.17 Therefore, we surveyed hospitals, given that they typically operate numerous outpatient practices. Because patient portal access policies could vary by geographic region or by organizational structure, we aimed to survey 1 independent hospital and 1 health system–affiliated hospital from every US state and the District of Columbia. We used the 2016 American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database to generate a list of all hospitals stratified by ownership (either health system–affiliated or independent). From this data set, we used stratified simple random sampling to select 1 health system–affiliated hospital and 1 independent hospital from each state and the District of Columbia. We excluded specialty hospitals (ascertained from the hospital website review) and those that did not have a patient portal (ascertained from the telephone interviews). Excluded hospitals were replaced with another randomly selected hospital within the same stratum. Health systems that spanned multiple states were included only once in the sample. We used REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University) to gather and store information from our website investigations and telephone interviews.18

Telephone Interview and Interview Script

One of us (R.K.W.W.) or another female data collector contacted personnel at each randomly selected hospital by telephone between May 21, 2018, and December 20, 2018. We called the patient portal technical support or general information telephone number listed on the website. Each hospital was called until a staff member was reached for the interview. After a minimum of 5 calls without making contact with personnel, we excluded the hospital and replaced it with another randomly selected hospital.

A standardized interview script was developed to investigate how hospitals advised caregivers to access the patient’s portal information (eAppendix in the Supplement). The interviewer pretended to be seeking information on behalf of her mother, who was going to be moving to the hospital’s region. The script was pilot tested on several hospitals (not included in the sample) and then revised.

The interviewer first asked personnel, usually either an information technology support staff member or a medical records employee, whether the hospital had a patient portal in place. The interviewer then asked if she could create her own account that would allow her to see her mother’s information to help manage her care. If the hospital provided proxy accounts, the interviewer inquired about the setup process. The interviewer then asked, “Wouldn’t it just be easier for my mother to share her password?” and recorded whether the staff member agreed, was noncommittal, or discouraged her from using her mother’s login credentials. After stating that her mother was private about some of her patient information, the interviewer asked whether her mother could limit the types of information available on the portal, such as only upcoming appointments.

If the hospital did not provide proxy accounts, the interviewer asked the staff member, “How can I get access to my mother’s upcoming appointments and medications if I can't create my own account?” The interviewer recorded whether personnel recommended she use her mother’s password.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (count and percentage) were calculated for variables of interest. We used χ2 tests to examine the associations between hospital type and the outcomes of interest as well as between proxy access and password sharing. Logistic regression was performed to examine the association between hospital type and password sharing, adjusting for proxy access. All analyses were performed from December 2018 to August 2019, using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

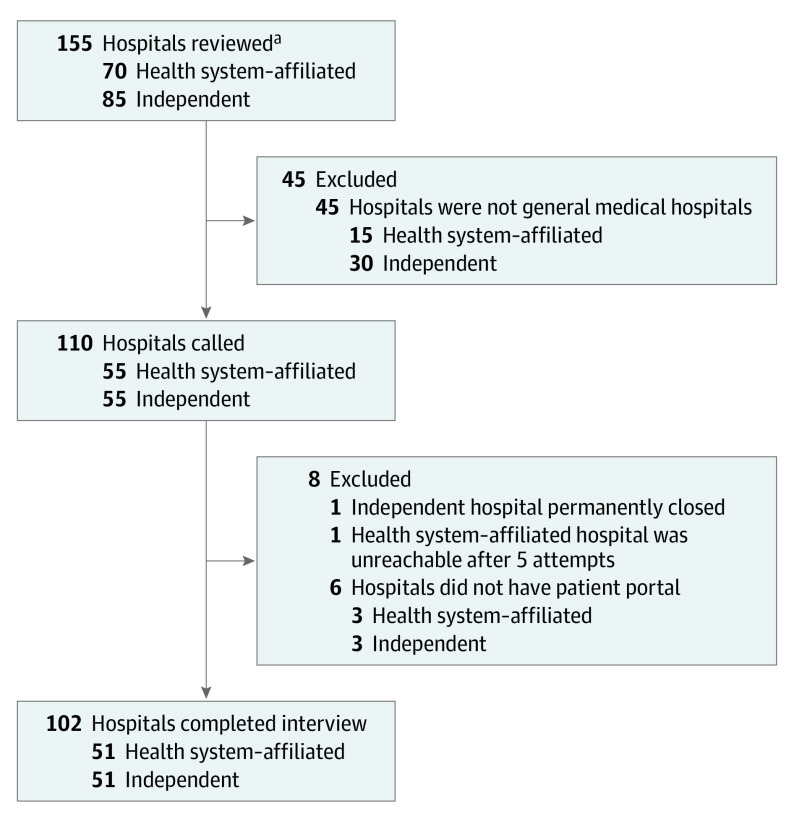

In total, the websites of 155 randomly selected hospitals were reviewed (Figure). Of these hospitals 70 (45%) were health system–affiliated and 85 (55%) were independent. Forty-five hospitals were excluded for not being general medical hospitals. The remaining 110 hospitals (55 health system–affiliated and 55 independent) were contacted, and an additional 8 were excluded. The final sample of 102 eligible hospitals (66% of the original 155 reviewed; 51 health system–affiliated and 51 independent) consisted of 1 health system–affiliated hospital and 1 independent hospital from each state and the District of Columbia.

Figure. CONSORT Diagram.

aOne health system–affiliated hospital and 1 independent hospital were randomly selected from each state and the District of Columbia. Ineligible or excluded hospitals were replaced with the next randomly selected hospital within the same stratum.

Adult Proxy Account Availability

In this sample, 69 of 102 hospitals (68%) offered proxy accounts to caregivers of adult patients and 26 (25%) did not. For the remaining 7 hospitals (7%), the personnel were unsure whether proxy access to patient portals was available. Hospitals that were part of a larger health system were more likely than independent hospitals to offer proxy accounts (41 of 51 [80%] vs 28 of 51 [55%]; P = .006).

Informational Controls

Among the 69 hospitals that provided proxy accounts to caregivers of adults, only 13 (19%) allowed patients to limit the types of information seen by their proxies. More independent hospitals than system-affiliated hospitals offered information limits for proxy accounts, but the difference was not statistically significant (8 of 28 [29%] vs 5 of 41 [12%]; P = .09).

Proxy Account Setup

For the 69 hospitals that provided proxy accounts, the setup processes varied considerably. Overall, 21 of these hospitals (30%) required the patient and the proxy to be physically present at one of their facilities while the account was created. Another 20 hospitals (29%) expected the patient to set up the proxy account while onsite but did not require the proxy to be present. The remaining 28 hospitals (41%) approved starting the account setup from home, either by filling in and mailing a paper application or by completing an online form.

Promotion of Password Sharing

Of the 102 hospital personnel we contacted, 94 (92%) were asked about password sharing; 42 of the 94 personnel (45%) recommended that the interviewer ask her mother to share her login credentials. Approximately one-quarter (23 [24%]) were noncommittal about the best way for the interviewer to access her mother’s patient portal, neither recommending nor advising against password sharing. Only 29 staff members (31%) actively discouraged sharing login credentials. Furthermore, personnel of 19 of 25 hospitals that did not provide proxy accounts (76%) advised password sharing compared with only 23 of 69 hospitals with proxy accounts (33%; P < .001) (Table). Independent hospitals were more likely than system-affiliated hospitals to endorse password sharing (29 of 47 [62%] vs 13 of 47 [28%]; P = .002). This association remained even after adjusting for the availability of proxy access (odds ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.2-7.8; P = .02).

Table. Advice Regarding Password Sharinga.

| Advice from hospital personnel | Hospitals allowing proxy accounts, No. (%) (n = 94) | Total, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 69) | No (n = 25) | ||

| Share password, either because no proxy accounts are available or because it is easier than creating a proxy account | 23 (33) | 19 (76) | 42 (45) |

| Noncommittal regarding password sharing | 23 (33) | 0 (0) | 23 (24) |

| Do not share password | 23 (33) | 6 (24) | 29 (31) |

Personnel from 7 of the 102 hospitals were unsure if their hospital allowed proxy accounts and thus were not asked about password sharing, and 1 staff member said “don’t know” when the interviewer asked how she could access her mother’s account without a proxy account.

Discussion

In this sample of randomly selected hospitals drawn from every US state and the District of Columbia, almost half of the hospital personnel recommended that patients share passwords with their caregivers, either because doing so was easier than creating a proxy account or because proxy accounts were not available. However, sharing login credentials has been associated with enormous security risks because people often reuse their passwords for different accounts, such as online banking or social media.19,20 Furthermore, advising patients to share passwords could violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Security Rule, which requires health systems to grant unique credentials to each user of an EHR system.21 Although we acknowledge that the responses of the personnel we surveyed may not reflect their respective hospital’s stated policies, at a minimum our findings indicate a need for rigorous training in proper security practices.

Although 68% of the hospitals we surveyed allowed proxy access, simply permitting proxy accounts is insufficient if the process for creating them is cumbersome. This finding is similar to results of other studies that have reported a substantial variation in the setup process, ranging from being created online to requiring an in-person visit.13 The setup process can also be complex. A recent usability study of 23 patients with chronic illness showed that almost none of them could establish a proxy account from within the patient portal.22 These barriers may explain why half of the caregivers in a large health system reported using the patient’s login credentials rather than creating a proxy account.10

Parallels can be seen between proxy accounts for caregivers of adults and proxy accounts for parents of children and adolescents. In a recent report, all 20 hospitals surveyed provided proxy access to parents of juvenile patients,16 but not all of these hospitals provided proxy access to caregivers of older adults. This finding suggests that the lack of proxy access to adult portals is associated with factors other than the technical limitations of EHR systems. Similarly, adolescent patients may have greater privacy protections compared with adult patients. Parents frequently have limited access to information in their child’s electronic record.23,24,25 In contrast, the present study found that only 19% of hospitals with proxy accounts gave adult patients the capability to limit the types of information shared with their caregivers. A study found that many patients were unaware of the full extent of information available on their portals11; furthermore, family members who served as caregivers noted that proxy accounts could divulge information that their loved one had previously withheld from them.26

Although this study highlighted the unintentional privacy risks of caregiver access to patient portals, eliminating all caregiver access would be a grave mistake. Research has demonstrated that caregiver access to patient portals can substantially improve the patient’s care,8,9,10,11 and thus caregiver access should be encouraged. We recommend that hospitals and EHR vendors work to expand the availability of secure proxy accounts and to simplify the setup process.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, because we stratified the hospital sample according to ownership, whether independent or system-affiliated, the results are reflective of practices within these strata but are not nationally representative overall. Second, the results reflect the knowledge of the patient portal support staff member who answered our survey questions and may not reflect the hospital’s official policies.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study found that almost half of surveyed hospital personnel appeared to endorse password sharing for accessing patient portal accounts and that few hospitals that allowed proxy access to those portals enabled patients to limit the types of information shared with their caregivers. Because caregiver access to patient portal accounts can improve care, this research demonstrated the need for hospitals and EHR vendors to improve the availability and setup process of proxy accounts, which would enable caregivers to access relevant health information without violating patient privacy.

eAppendix. Phone Interview Script

References

- 1.Adler-Milstein J, Holmgren AJ, Kralovec P, Worzala C, Searcy T, Patel V. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: the emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1142-1148. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah SD, Liebovitz D. It takes two to tango: engaging patients and providers with portals. PM R. 2017;9(5S):S85-S97. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zickuhr K, Madden M Older adults and internet use. Pew Research Center. Published June 6, 2012. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/06/06/older-adults-and-internet-use/

- 5.Greysen SR, Chin Garcia C, Sudore RL, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and internet use among older adults: implications for meaningful use of patient portals. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1188-1190. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Poll on Healthy Aging Logging in: using patient portals to access health information. Published June 2018. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/sites/default/files/2018-05/NPHA_Patient-Portal_051418_.pdf

- 7.Chimowitz H, Gerard M, Fossa A, Bourgeois F, Bell SK. Empowering informal caregivers with health information: OpenNotes as a safety strategy. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(3):130-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff JL, Berger A, Clarke D, et al. Patients, care partners, and shared access to the patient portal: online practices at an integrated health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(6):1150-1158. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vick JB, Amjad H, Smith KC, et al. “Let him speak:” a descriptive qualitative study of the roles and behaviors of family companions in primary care visits among older adults with cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(1):e103-e112. doi: 10.1002/gps.4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed ME, Huang J, Brand R, et al. Communicating through a patient portal to engage family care partners. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):142-144. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vizer LM, Eschler J, Koo BM, Ralston J, Pratt W, Munson S. “It’s not just technology, it’s people”: constructing a conceptual model of shared health informatics for tracking in chronic illness management. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e10830. doi: 10.2196/10830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar U, Bates DW. Care partners and online patient portals. JAMA. 2014;311(4):357-358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latulipe C, Quandt SA, Melius KA, et al. Insights into older adult patient concerns around the caregiver proxy portal use: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10524. doi: 10.2196/10524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semere W, Crossley S, Karter AJ, et al. Secure messaging with physicians by proxies for patients with diabetes: findings from the ECLIPPSE Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2490-2496. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05259-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff JL, Darer JD, Larsen KL. Family caregivers and consumer health information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):117-121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3494-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff JL, Kim VS, Mintz S, Stametz R, Griffin JM. An environmental scan of shared access to patient portals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(4):408-412. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Physicians Foundation, Merritt Hawkins 2018 Survey of America's physicians: practice patterns and perspectives. Copyright 2018. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/physicians-survey-results-final-2018.pdf

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das A, Bonneau J, Caesar M, Borisov N, Wang X. The tangled web of password reuse. NDSS Symposium. Published February 2014. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/06_1_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florencio D, Herley C A large-scale study of web password habits. Presented at: 16th International Conference on World Wide Web; May 8, 2007; Banff, Alberta, Canada. Accessed November 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Security standards: technical safeguards. Revised March 2007. Accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/techsafeguards.pdf

- 22.Ali SB, Romero J, Morrison K, Hafeez B, Ancker JS. Focus section health IT usability: applying a task-technology fit model to adapt an electronic patient portal for patient work. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(1):174-184. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1632396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourgeois FC, Taylor PL, Emans SJ, Nigrin DJ, Mandl KD. Whose personal control? Creating private, personally controlled health records for pediatric and adolescent patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(6):737-743. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webber EC, Brick D, Scibilia JP, Dehnel P; Council on Clinical Information Technology; Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management; Section on Telehealth Care Electronic communication of the health record and information with pediatric patients and their guardians. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20191359. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharko M, Wilcox L, Hong MK, Ancker JS. Variability in adolescent portal privacy features: how the unique privacy needs of the adolescent patient create a complex decision-making process. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(8):1008-1017. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crotty BH, Walker J, Dierks M, et al. Information sharing preferences of older patients and their families. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1492-1497. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Phone Interview Script