Key Points

Question

Does the response to rituximab differ between patients with new-onset vs refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and how does rituximab compare with conventional immunotherapy in these patients?

Findings

In this cohort study of 72 patients exposed to rituximab early or later in the myasthenia gravis disease course as well as controls receiving conventional immunotherapy, rituximab appeared to perform better if initiated early after onset of generalized symptoms.

Meaning

Early treatment with rituximab may be associated with improved treatment outcomes and may be considered earlier in the treatment algorithms for patients with new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis.

Abstract

Importance

Use of biologic agents in generalized myasthenia gravis is generally limited to therapy-refractory cases; benefit in new-onset disease is unknown.

Objective

To assess rituximab in refractory and new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis and rituximab vs conventional immunotherapy in new-onset disease.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study with prospectively collected data was conducted on a county-based community sample at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Participants included 72 patients with myasthenia gravis, excluding those displaying muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies, initiating rituximab treatment from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2018, and patients with new-onset disease initiating conventional immunotherapy from January 1, 2003, to December 31, 2012, with 12 months or more of observation time. The present study was conducted from March 1, 2019, to January 31, 2020.

Exposures

Treatment with low-dose rituximab (most often 500 mg every 6 months) or conventional immunosuppressants.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Time to remission (main outcome) as well as use of rescue therapies or additional immunotherapies and time in remission (secondary outcomes).

Results

Of the 72 patients included, 31 patients (43%) were women; mean (SD) age at treatment start was 60 (18) years. Twenty-four patients had received rituximab within 12 months of disease onset and 48 received rituximab at a later time, 34 of whom had therapy-refractory disease. A total of 26 patients (3 [12%] women; mean [SD] age, 68 [11] years at treatment start) received conventional immunosuppressant therapy. Median time to remission was shorter for new-onset vs refractory disease (7 vs 16 months: hazard ratio [HR], 2.53; 95% CI, 1.26-5.07; P = .009 after adjustment for age, sex, and disease severity) and for rituximab vs conventional immunosuppressant therapies (7 vs 11 months: HR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.43-6.18; P = .004 after adjustment). In addition, fewer rescue therapy episodes during the first 24 months were required (mean [SD], 0.38 [1.10] vs 1.31 [1.59] times; mean difference, −1.26; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.56; P < .001 after adjustment), and a larger proportion of patients had minimal or no need of additional immunotherapies (70% vs 35%; OR, 5.47; 95% CI, 1.40-21.43; P = .02 after adjustment). Rates of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events were lower with rituximab compared with conventional therapies (3% vs 46%; P < .001 after adjustment).

Conclusions and Relevance

Clinical outcomes with rituximab appeared to be more favorable in new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis, and rituximab also appeared to perform better than conventional immunosuppressant therapy. These findings suggest a relatively greater benefit of rituximab earlier in the disease course. A placebo-controlled randomized trial to corroborate these findings is warranted.

This cohort study compares the use of rituximab in patients with refractory and new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis as well as in patients receiving conventional immunotherapy.

Introduction

Acquired myasthenia gravis (MG) is caused by an autoreactive humoral response against the postsynaptic end plate of the neuromuscular junction, with a prevalence of 24.8 to 27.8 per 100 000 in a Swedish nationwide study.1,2 Myasthenia gravis can be stratified based on age, autoantibodies, presence of thymoma, and clinical symptoms, all of which may affect treatment response.3,4,5 Myasthenia gravis represents a potentially life-threatening condition, but increased use of immunomodulatory drugs over the past decades has been associated with an improved prognosis.6 In current treatment guidelines, corticosteroids are used as first-line therapy for patients displaying residual symptoms with choline esterase blockers.7 Due to adverse effects of corticosteroids, especially after long-term use, it is common to add a steroid-sparing oral immunosuppressant, such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, or tacrolimus. Still, a proportion of patients respond poorly to therapy (ie, refractory disease).7 In these cases, cycles of intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, or cyclophosphamide can be considered.7 Collectively, however, the use of these conventional treatments is based mostly on empirical evidence rather than formal randomized clinical trials.

Positive results from REGAIN, an international, multicenter, placebo-controlled, phase 3 randomized clinical trial in refractory acetylcholine receptor antibody–positive MG, led to the approval of eculizumab, a complement 5a blocker.8 Additional biologic agents, such as blockers of the neonatal Fc-receptor, are also in clinical development.9 Given the heterogeneity of MG, it is likely that additional biologic agents, some of which may already be approved for other conditions, can be effective.10 One example is rituximab, a B-cell–depleting monoclonal antibody approved for treatment of B-cell lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic vasculitis. A meta-analysis has reported what appear to be encouraging results with rituximab in refractory disease; however, this study was based mainly on smaller case series.11 More recently, an Austrian nationwide, retrospective, noncontrolled study reported favorable short-term outcomes in a mixed cohort of 56 patients with refractory disease, in which presence of muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK+) antibodies was independently associated with a favorable treatment response.12 This finding corroborates an observational study comparing outcomes with rituximab and conventional treatment specifically in MuSK+ MG.13 In contrast, preliminary results from a recent randomized clinical trial in refractory acetylcholine receptor antibody–positive MG (BEAT-MG; study results not published in full) failed to show the benefit of rituximab over placebo with reduction in corticosteroid use as the primary outcome.14 Studies examining the effect of biologic agents in new-onset MG are still rare. The objective of this study was to compare outcomes with rituximab started early or later after disease onset in non-MuSK+ generalized MG (gMG) as well as between rituximab and conventional immunosuppressants in new-onset gMG using time to remission as the main outcome and time in remission, use of rescue therapies, and total amount of immunosuppressive therapies as secondary outcomes. Study outcomes were specified before data analysis.

Methods

The Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, hosts the only referral center for gMG in Stockholm County (population 2 344 124 as of December 31, 2018). Patients were identified through the National MG registry (https://neuroreg.se/), covering greater than 80% of all types of MG in the Stockholm region,2 as well as local medical records. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee of Stockholm, and participants had given oral consent to registration in the National MG registry and the use of recorded data for research purposes. The study was conducted from March 1, 2019, to January 31, 2020. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Of 479 patients with MG registered at the Karolinska University Hospital referral center, 202 are actively followed up with clinical controls. We identified patients residing in Stockholm County who received 1 or more dose of rituximab before December 31, 2018. The first patient with refractory gMG, defined as an inadequate response to therapy with 1 or more immunosuppressant (including daily corticosteroids at doses ≥10 mg over a minimum of 3 months) and 12 or more months since disease onset, received rituximab in 2010 and the first patient with new-onset gMG, defined as no immunosuppressant exposure and less than 12 months since generalized disease onset, in 2013. The following exclusion criteria were applied: presence of anti-MuSK+ antibodies, less than 12 months’ observation time, a maximum Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) score of less than 4 during the year preceding treatment start, less than 2 recorded follow-up visits, initiation or follow-up of rituximab treatment outside of Stockholm County, concurrent neurologic diseases interfering with the assessments, and immunosuppressive therapy for other indications during the observation period. The QMG is a 13-item scale; each item is scored from 0 (no impairment) to 3 (severe impairment), yielding a total score with a possible range from 0 to 39. We also identified a control group of patients with new-onset gMG diagnosed between 2003 and 2012, ie, preceding the shift to use of rituximab, applying the same inclusion and exclusion criteria except for initiation of conventional immunosuppressants (monotherapy with corticosteroids excluded) within 1 year of disease onset as an inclusion criterion.

Patients were censored at last available follow-up or migration (n = 1), whichever came first. Four patients whose treatment was switched to other biologic agents—2 in the new-onset group and 2 in the refractory rituximab group—were censored 6 months after the last rituximab infusion, whereas 10 patients whose treatment was switched to rituximab in the conventional immunotherapy group were censored at the first rituximab infusion. Seven patients died during follow-up: 1 in the rituximab group with new-onset gMG (93 years, 47 months’ follow-up), 1 in the rituximab group with refractory gMG (86 years, 52 months’ follow-up), and 5 in the conventional immunosuppressant group (mean [SD], 83 [9] years, 98 [34] months’ follow-up).

Demographic and clinical variables were collected from the National MG registry and validated against electronic medical records (Table). A recorded QMG was available for 564 of 1002 total visits (54%), and 92 of 99 patients (93%) had at least 1 recorded QMG score (Table). If missing, the QMG score was calculated from the recorded neurologic status. The reconstructed QMG score was compared and calibrated with recorded QMG scores for all clinical assessors, with a minimum of 1 recorded score per physician; however, for most patients, more than 3 scores were used for calibration. Differences between reconstructed and recorded QMG scores were accepted if ±1 point for scores less than 6 and ±2 points for scores greater than 6. All included patients had QMG scores greater than or equal to 4 with extraocular contribution before initiation of therapy. Clinical remission was defined as a QMG score less than or equal to 2 in the absence of rescue therapies or hospitalization due to worsening of MG symptoms during the 3 preceding months. Disease worsening was defined as a QMG score greater than or equal to 4, treatment with rescue therapy, and/or hospitalization. Age 50 years at disease onset was used as a cutoff point between early-onset (<50 years) and late-onset (≥50 years) MG. Intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, and intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, ≥1 g) were considered rescue therapies if given in the context of MG-related worsening, while chronic prophylactic intravenous immunoglobulin was considered an immunotherapy. The score designed by Hehir and colleagues,13 modified by including rituximab as an immunotherapy, was used as a global measure of immunotherapy. In brief, grade 0 designated only symptomatic treatment; grade 1, low-dose monotherapy; grade 2, low-dose therapy with 2 drugs; and grade 3, 2 drugs, with at least 1 of these administered in high doses in the past year. Treatment only with rituximab within the past 12 months was considered grade 1.

Table. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Rituximab | Control | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 72) | New-onset MG (n = 24) | Refractory MG (n = 34) | Untreated MG>12 mo (n = 14) | New-onset MG (n = 26) | Refractory vs new-onset MG, rituximab | New-onset MG, rituximab vs control | |

| Age at onset, mean (SD), y | 54 (19) | 57 (20) | 53 (18) | 52 (20) | 68 (11) | .49 | .02 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||||

| Men | 41 (57) | 14 (58) | 20 (59) | 7 (50) | 23 (88) | NA | NA |

| Women | 31 (43) | 10 (42) | 14 (41) | 7 (50) | 3 (12) | >.99 | .78 |

| Early-onset MG, No. (%) | 26 (36) | 9 (38) | 11 (32) | 6 (43) | 3 (12) | .78 | .02 |

| Acetylcholine receptor antibody–positive, No. (%) | 60 (83) | 20 (83) | 28 (82) | 12 (86) | 24 (92) | .47 | .24 |

| Thymectomy, No. (%) | 30 (42) | 9 (38) | 16 (47) | 5 (36) | 11 (42) | .59 | .78 |

| Hyperplasia, No. (%) | 12 (17) | 4 (17) | 5 (15) | 3 (21) | 0 | >.99 | .046 |

| Thymoma, No. (%) | 10 (14) | 3 (13) | 5 (15) | 2 (14) | 6 (23) | >.99 | .47 |

| QMG score, mean (SD)a | |||||||

| Baseline | 7 (5) | 8 (4) | 7 (5) | 6 (5) | 8 (5) | .52 | .96 |

| Maximum | 10 (5) | 10 (5) | 11 (5) | 8 (4) | 11 (5) | .25 | .56 |

| Clinical visits | 8 (3) | 9 (2) | 8 (4) | 5 (2) | 16 (7) | .41 | <.001 |

| Reconstructed QMG score, No. (%) | 52 (30) | 50 (24) | 49 (31) | 36 (36) | 63 (28) | .88 | .09 |

| Age at treatment start, mean (SD), y | 60 (18) | 58 (20) | 63 (16) | 56 (19) | 68 (11) | .24 | .03 |

| Time from disease onset to treatment, mean (SD), mo | 67 (95) | 5 (4) | 122 (113) | 41 (39) | 5 (3) | <.001 | .39 |

| Follow-up time after treatment start, mean (SD), mo | 40 (19) | 44 (15) | 40 (23) | 30 (15) | 97 (40) | .44 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: MG, myasthenia gravis; NA, not applicable; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis.

The QMG score is a 13-item scale; each item is scored from 0 (no impairment) to 3 (severe impairment), yielding a total score with a possible range from 0 to 39.

We adopted a low-dose protocol used for multiple sclerosis in Sweden, consisting of a single infusion of rituximab, 500 mg, every 6 months.15,16,17 Some patients received only 100 mg as a single infusion based on a small study in multiple sclerosis.18 In patients displaying a good clinical response, infusion intervals were sometimes prolonged or therapy was discontinued. Conventional immunotherapy was defined as prednisolone, azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil. Low-dose therapy was defined as prednisolone, less than 20 mg/d; tacrolimus, less than 5 mg/d; methotrexate, less than 15 mg/wk; azathioprine, less than 150 mg/d; mycophenolate mofetil, less than 2000 mg/d; and cyclosporine, less than 100 mg/d.13

Statistical Analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics between groups were evaluated with a 2-tailed Fisher exact test for categorical variables and a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for quantitative variables. Quantitative variables are reported as mean (SD). Group differences in time to relapse and remission were assessed through Kaplan-Meier curves and univariate (crude) and multivariable (adjustment for age, sex, and severity, ie, QMG score at baseline and maximum score in past year) hazard ratios (HRs) from Cox proportional hazards regression. Differences in the proportion of patients in remission at 12 and 24 months and in treatment grade 0 or 1 was estimated with odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression crude data as well as those adjusted for age, sex, and severity. For the number of rescue therapy episodes, a 2-tailed t test was used, and adjusted mean differences were estimated in linear regression. Prism 7 (GraphPad Software) was used for unadjusted statistical tests, and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for all regression models. P values <.05 were considered significant.

Results

Study Population

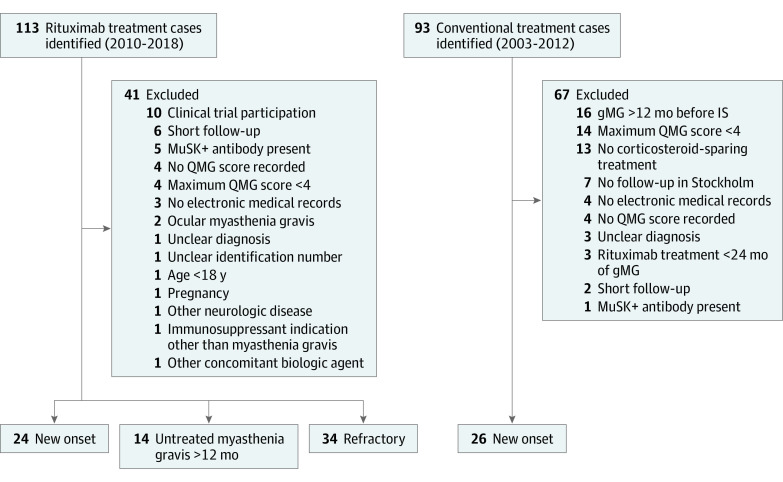

We identified 113 patients with MG who received rituximab treatment; of these, 72 patients fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of the 72 patients included, 31 patients (43%) were women; mean (SD) age at treatment start was 60 (18) years. Twenty-four of these patients had new-onset disease (10 [42%] women; mean [SD] disease duration at rituximab initiation, 5 [4] months), while 34 started rituximab 12 or more months from disease onset and after treatment with at least 1 conventional immunosuppressant (refractory rituximab group; 14 [41%] women; mean time to rituximab initiation, 122 [113] months) (Figure 1; eTable in the Supplement). In addition, 14 patients received their first rituximab treatment more than 12 months after disease onset, fulfilling the QMG criteria for severity but not for previous exposure to immunotherapy (7 [50%] women; mean time to rituximab treatment, 41 [39] months) (Figure 1). Three patients received rituximab, 1000 mg, at the first infusion; the rituximab dose was 500 mg for 57 patients and 100 mg for 12 patients. Subsequent infusions were given at a dose of 500 mg for all but 3 patients who received 100 mg. Lymphocyte profiles at 6 months ±8 weeks were available for 36 patients; of these, 19 patients (53%) had CD19+ B cells below the detection limit (<0.01 × 109/L), 10 patients (28%) had low levels (0.01 × 109/L-0.03 × 109/L), and 7 patients (19%) had CD19+ B-cell counts greater than 0.03 × 109/L, similar to observations in patients with multiple sclerosis using this dosing.19 There was no clear association between attaining remission or time to remission and B-cell counts before the start of rituximab therapy, at readministration of the drug, or rituximab dose.

Figure 1. Recruitment of Patients With Generalized Myasthenia Gravis (gMG).

Patient recruitment to the rituximab and conventional treatment groups, respectively. Time frames for inclusion based on start of inclusion therapy as well as reasons for exclusion in the respective groups, are indicated. IS indicates immunosuppressant therapy; MuSK+, muscle-specific tyrosine kinase-positive; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis.

Baseline characteristics were largely similar, including disease severity as reflected by the most recent QMG score before initiation of rituximab therapy and maximum QMG score in the preceding year (Table). The mean observation time following rituximab initiation was 44 (15) months in the new-onset group (total follow-up, 1067 months) and 40 (23) months in therapy-refractory cases (total follow-up, 1443 months).

The control cohort consisted of patients initiating conventional immunosuppressive therapies. Of 105 patients diagnosed with MG from 2003 to 2012, 93 patients (89%) had generalized disease and 26 patients (28%, 3 [12%] women) fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The main reasons for exclusion were no corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressant therapy initiated within 12 months and QMG score less than 4. Ten of the 26 patients were later censored when treatment was switched to rituximab (mean time from conventional immunosuppressive treatment, 84 [28] months). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in the rituximab vs control groups except for younger age (57 [20] vs 68 [11] years, P = .02) as well as a higher proportion of patients with early-onset MG (9 [38%] vs 3 [12%], P = .02) and hyperplasia among those who underwent thymectomy (4 [17%] vs 0, P = .046) (Table). Mean follow-up time was longer in the control group (97 [40] vs 44 [15] months, P < .001; total follow-up time, 2453 vs 1067 months).

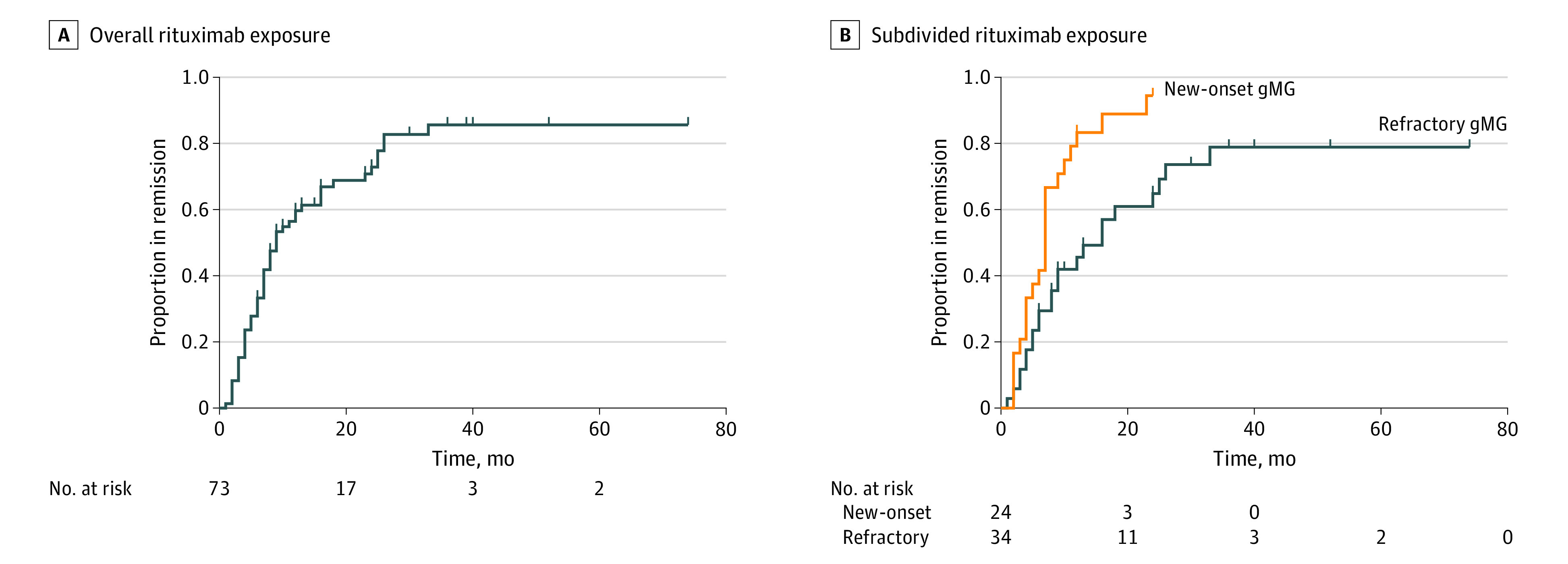

During the observation time, 55 of 72 rituximab-treated patients (76%) fulfilled our criteria for clinical remission, in which time to remission was shorter in the new-onset group compared with therapy-refractory patients (7 vs 16 months: HR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.26-5.07; P = .009 after adjustment for age, sex, and disease severity) (Figure 2). Analyses of median time to remission in the whole rituximab-treated cohort (n = 72) did not reveal marked differences across disease subsets: early vs late onset (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.48-3.75; P = .57), women vs men (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.66-2.14; P = .56), thymectomy vs no thymectomy (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.64-2.55; P = .49), thymoma vs no thymoma (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.52-2.10; P = .90), and hyperplasia vs no hyperplasia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.42-2.69; P = .89). Hence, of all evaluated characteristics, only time from onset of generalized disease to initiation of rituximab therapy displayed a significant predictive value for attaining remission.

Figure 2. Time to Remission From Start of Rituximab Treatment.

Remission in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) exposed to rituximab in the entire cohort (n = 72) (A) and subdivided into new-onset disease (n = 24) and therapy-refractory cases (n = 34) (B).

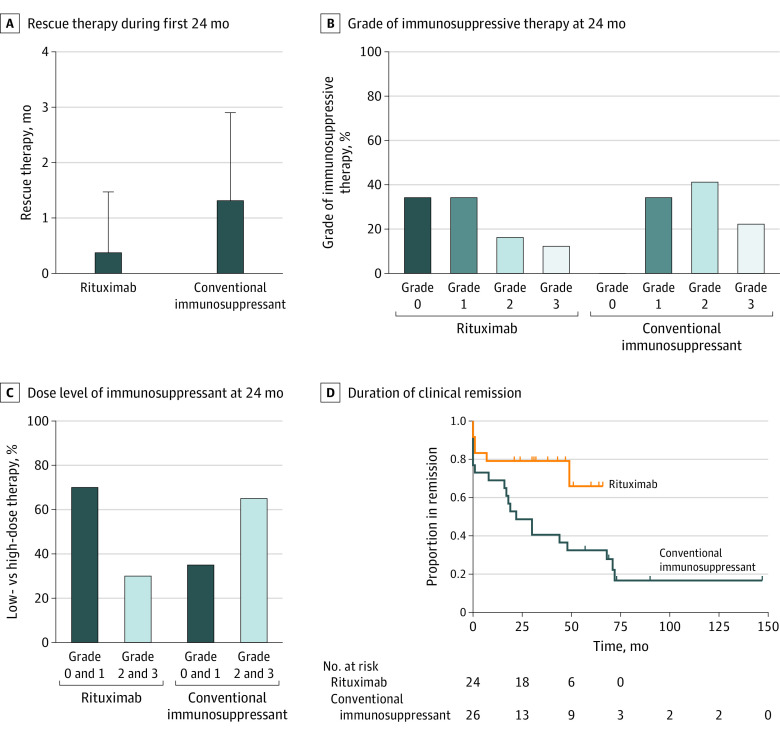

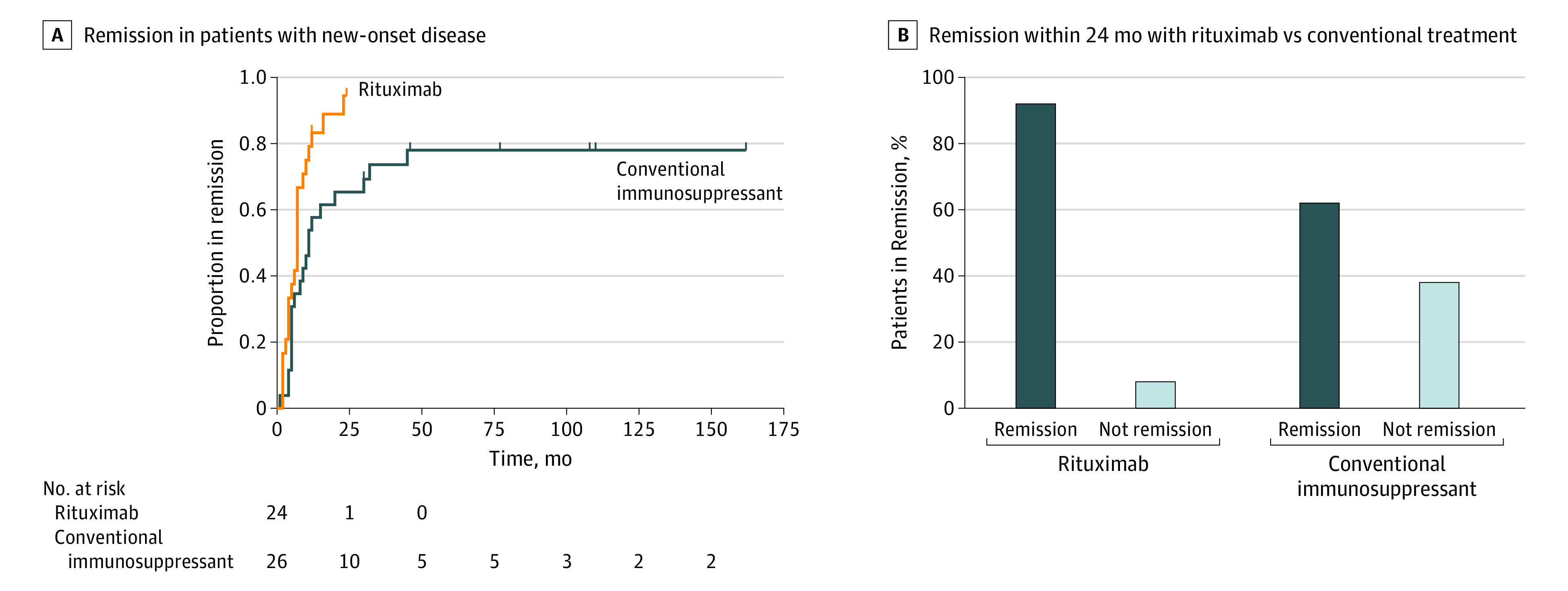

The 24 patients with new-onset gMG receiving rituximab therapy went into clinical remission significantly faster than the 26 patients in the control group receiving conventional immunotherapies (7 vs 11 months: HR, 2.97; 95% CI, 1.43-6.18; P = .004 after adjustment for sex, age, and disease severity) (Figure 3A). Furthermore, in a post hoc analysis, the proportions of patients in clinical remission at 12 and 24 months were larger with rituximab than conventional immunotherapies (12 months: 20/23 [87%] rituximab-treated vs 15/26 [58%] controls; OR, 14.04; 95% CI, 1.82-108.59; P = .01 after adjustment and 24 months: 22/23 [96%] rituximab-treated vs 16/26 [62%] controls; OR, 21.34; 95% CI, 1.14-401.12; P = .004 after adjustment) (Figure 3B). In addition, rituximab-treated patients required fewer rescue therapies during the first 24 months of observation compared with the control group (mean [SD], 0.38 [1.10] vs 1.31 [1.59] occasions; mean difference, −1.26; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.56; P < .001 after adjustment) (Figure 4A). Other findings were also in favor of rituximab, including the global measure of immunotherapy use. Thus, rituximab-treated patients were tapered off immunomodulatory drugs more rapidly, including corticosteroids, with 8 of 23 patients (35%) reaching grade 0 (no immunotherapy) at 24 months from the start of therapy; the corresponding figure for the control group was 0% (Figure 4B). The proportion of patients in grades 0 and 1 was significantly greater with rituximab than conventional immunotherapy (70% vs 35%; OR, 5.47; 95% CI, 1.40-21.43; P = .02 after adjustment) (Figure 4C). Rituximab was also associated with more sustained remission compared with conventional immunotherapy (median, 22 months for conventional immunotherapy; data not available for the rituximab group since 75% [18/24] remained in remission; HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.10-0.95; P = .04 after adjustment) (Figure 4D).

Figure 3. Time to Remission After Exposure to Rituximab or Conventional Immunotherapy in New-Onset Myasthenia Gravis.

Kaplan-Meier curve of patients reaching clinical remission in new-onset patients treated with rituximab or conventional immunotherapy (A), and proportion of patients in remission within 24 months after treatment start (B).

Figure 4. Additional Therapies and Proportion Remaining in Remission in Myasthenia Gravis Patients Exposed to Rituximab or Conventional Immunosuppressive Treatment, Respectively.

Number of episodes requiring rescue therapy during the first 24 months after initiating treatment (error bars indicate SD) (A). Proportions of patients (%) in each grade of a global measure of immunotherapies including rituximab after 24 months (B) and frequency treated with low-dose immunosuppressants at 24 months (C). Duration of clinical remission in patients with new-onset disease treated with rituximab or conventional immunotherapy (D).

Rituximab also was associated with a lower rate of drug discontinuation due to adverse events (3% vs 46%, P < .001), suggesting better tolerability than with conventional immunotherapy. In the conventional immunotherapy group, 12 of 26 patients (46%) discontinued at least 1 drug owing to adverse effects, while 7 patients (27%) discontinued 2 or more immunosuppressive drugs. Most patients (10/12 [83%]) who discontinued treatment in the control group did so within 18 months, thus allowing for a fair comparison despite differences in follow-up time. Of 72 rituximab-treated individuals, 8 patients (11%) experienced mild and transient infusion-related symptoms, such as flushing, malaise, and fever. Two patients discontinued rituximab treatment owing to adverse effects: 1 with an allergic infusion reaction at the second infusion (subsequently treated with ofatumumab but later switched back to rituximab) and 1 with recurrent episodes of pneumonia.

Discussion

The 2 main findings of this study are that treatment outcomes were more favorable with rituximab started early after disease onset of non-MuSK+ gMG, and rituximab in this patient group performed better than conventional immunosuppressants. Together, these findings suggest consideration for placing rituximab earlier in the treatment algorithm because it is now considered a possible third-line option.7

In multiple sclerosis, an earlier start of effective treatment is associated with reduced damage to neuroaxonal connections associated with lifelong neurologic disabilities.20,21 In MG, the argument for early treatment with rituximab arises more from an immunologic viewpoint. Anti-CD20 biologic agents deplete all immature and mature B cells, memory B cells, and some plasmablasts but do not directly affect plasma cells.22 Hence, B-cell–depleting therapies exert limited effects on total immunoglobulin G concentrations even after long-term exposure because humoral immunity is maintained by long-lived plasma cells.16,23 How these cells are formed is not clearly understood, but evidence indicates that antibodies in early immune responses mainly derive from plasmablasts and short-lived plasma cells.24 A selection process takes place with persistent antigen stimulation, in which some cells develop into long-lived plasma cells.25,26,27,28 One may thus speculate whether early treatment with rituximab limits the buildup of a disease-associated, antibody-producing plasma cell pool.29 The role of B cells in autoimmune diseases is nevertheless complex and includes effects mediated by B-cell–derived cytokines on T cells and plasma cells as well as the complement system.30,31 In addition, a nonredundant role of memory B cells for antigen-specific activation of memory T cells in multiple sclerosis was recently shown.32 Evidence for a more complex dysregulation of B cells that is not attributable only to antibodies is also evident in MG.33

A beneficial treatment response was observed with a lower rituximab dose than traditionally used (ie, a single 500-mg infusion) vs the most used MG regimen of 4 separate infusions of 375 mg/m2,11,13,34,35 although a recent noncontrolled study reported outcomes with a 600-mg dose.36 In multiple sclerosis, doses of 500 and 1000 mg displayed apparently comparable effects on disease activity and depletion of B cells.16 Even if extrapolation of data across diseases is not straightforward, it is possible that lower doses and avoiding exposure to combinations of immunosuppressants are associated with improved safety, not the least of which involves the risk of infections.37

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of the present study include the nonrandomized, retrospective observational design, which makes it sensitive to confounding by indication, ie, that all factors affecting choice of therapy cannot be accounted for. However, we took advantage of a relatively fast change in treatment practices when rituximab became a preferred first choice for immunotherapy, which allowed us to select a control group diagnosed before this change in priority had occurred, resulting in reduced selection bias for therapeutic channeling. However, inclusion of this group introduced a difference in observation time, and a larger proportion of patients in the conventional treatment group was excluded owing to incomplete medical records. Further limitations include data being collected during routine clinical practice rather than a formal study setting, which meant that both quality and quantity of clinical data varied among patients and that sizes of many subgroups were too small to allow for conclusions on possible differences. There were also some imbalances in baseline characteristics between the new-onset cohorts. Statistical corrections for age, sex, and disease severity, however, did not change the main findings. There are also strengths of the study, including the use of an MG registry with high coverage and a defined population-based patient uptake area, which increase the external validity of results, ie, the possibility to extrapolate results to the studied patient populations.

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective cohort study of rituximab-treated patients with non-MuSK+ gMG suggest that initiation of therapy early after diagnosis may be associated with improved outcomes and good tolerability compared with treatment with conventional immunotherapies. Collectively, these findings suggest that rituximab also should be considered earlier in the treatment algorithm for non-MuSK+ gMG. Conclusions about the clinical effectiveness of rituximab in new-onset gMG must await results from an ongoing randomized clinical trial (NCT02950155)38 with results expected in 2021.

eTable. Patient Characteristics: Therapy-Refractory Group

References

- 1.Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, Palace J, Burns TM, Verschuuren JJGM. Myasthenia gravis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):30. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0079-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang F, Sveinsson O, Thormar G, et al. . The autoimmune spectrum of myasthenia gravis: a Swedish population-based study. J Intern Med. 2015;277(5):594-604. doi: 10.1111/joim.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berrih-Aknin S, Le Panse R. Myasthenia gravis: a comprehensive review of immune dysregulation and etiological mechanisms. J Autoimmun. 2014;52:90-100. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1023-1036. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00145-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilhus NE, Skeie GO, Romi F, Lazaridis K, Zisimopoulou P, Tzartos S. Myasthenia gravis—autoantibody characteristics and their implications for therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(5):259-268. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T, Pagala M. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37(2):141-149. doi: 10.1002/mus.20950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, et al. . International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87(4):419-425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard JF Jr, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, et al. ; REGAIN Study Group . Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):976-986. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30369-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard JF Jr, Bril V, Burns TM, et al. ; Efgartigimod MG Study Group . Randomized phase 2 study of FcRn antagonist efgartigimod in generalized myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2019;92(23):e2661-e2673. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalakas MC. Immunotherapy in myasthenia gravis in the era of biologics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(2):113-124. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0110-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iorio R, Damato V, Alboini PE, Evoli A. Efficacy and safety of rituximab for myasthenia gravis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2015;262(5):1115-1119. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7532-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topakian R, Zimprich F, Iglseder S, et al. . High efficacy of rituximab for myasthenia gravis: a comprehensive nationwide study in Austria. J Neurol. 2019;266(3):699-706. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09191-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hehir MK, Hobson-Webb LD, Benatar M, et al. . Rituximab as treatment for anti-MuSK myasthenia gravis: multicenter blinded prospective review. Neurology. 2017;89(10):1069-1077. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowak RJ, Coffey C, Goldstein J, et al. . B-cell targeted treatment in myasthenia gravis (BeatMG): a phase 2 trial of rituximab in myasthenia gravis: topline results. Neurology. 2018;90(24):e2182-e2194. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. . Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):950-958. doi: 10.1002/ana.24651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzer J, Svenningsson R, Alping P, et al. . Rituximab in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational study on safety and efficacy. Neurology. 2016;87(20):2074-2081. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granqvist M, Boremalm M, Poorghobad A, et al. . Comparative effectiveness of rituximab and other initial treatment choices for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(3):320-327. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen AS, Miravalle A, Langer-Gould A, Cooper J, Edwards KR, Kinkel RP. Maximally tolerated versus minimally effective dose: the case of rituximab in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18(3):377-378. doi: 10.1177/1352458511418631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn N, Juto A, Ryner M, et al. . Rituximab in multiple sclerosis: frequency and clinical relevance of anti-drug antibodies. Mult Scler. 2018;24(9):1224-1233. doi: 10.1177/1352458517720044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovannoni G, Butzkueven H, Dhib-Jalbut S, et al. . Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9(suppl 1):S5-S48. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, et al. . Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):43. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barun B, Bar-Or A. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with anti-CD20 antibodies. Clin Immunol. 2012;142(1):31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann RM, Furst DE, Lacey S, Lehane PB. Longterm safety of rituximab: final report of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Global Clinical Trial Program over 11 years. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(10):1761-1766. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chihara N, Aranami T, Sato W, et al. . Interleukin 6 signaling promotes anti-aquaporin 4 autoantibody production from plasmablasts in neuromyelitis optica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(9):3701-3706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017385108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM. The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(3):160-171. doi: 10.1038/nri3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sze DM, Toellner KM, García de Vinuesa C, Taylor DR, MacLennan IC. Intrinsic constraint on plasmablast growth and extrinsic limits of plasma cell survival. J Exp Med. 2000;192(6):813-821. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González-García I, Rodríguez-Bayona B, Mora-López F, Campos-Caro A, Brieva JA. Increased survival is a selective feature of human circulating antigen-induced plasma cells synthesizing high-affinity antibodies. Blood. 2008;111(2):741-749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hargreaves DC, Hyman PL, Lu TT, et al. . A coordinated change in chemokine responsiveness guides plasma cell movements. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):45-56. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hachiya Y, Uruha A, Kasai-Yoshida E, et al. . Rituximab ameliorates anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis by removal of short-lived plasmablasts. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;265(1-2):128-130. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MR. Rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody): mechanisms of action and resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7359-7368. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li R, Patterson KR, Bar-Or A. Reassessing B cell contributions in multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(7):696-707. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0135-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jelcic I, Al Nimer F, Wang J, et al. . Memory B cells activate brain-homing, autoreactive CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Cell. 2018;175(1):85-100.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stathopoulos P, Kumar A, Heiden JAV, Pascual-Goñi E, Nowak RJ, O’Connor KC. Mechanisms underlying B cell immune dysregulation and autoantibody production in MuSK myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1412(1):154-165. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson D, Phan C, Johnston WS, Siddiqi ZA. Rituximab in refractory myasthenia gravis: a prospective, open-label study with long-term follow-up. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(7):552-555. doi: 10.1002/acn3.314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robeson KR, Kumar A, Keung B, et al. . Durability of the rituximab response in acetylcholine receptor autoantibody–positive myasthenia gravis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):60-66. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu J, Zhong H, Jing S, et al. . Low-dose rituximab every 6 months for the treatment of acetylcholine receptor-positive refractory generalized myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(3):311-315. doi: 10.1002/mus.26790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luna G, Alping P, Burman J, et al. . Infection risks among patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod, natalizumab, rituximab, and injectable therapies. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(2):184-191. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.A study evaluating the safety and efficacy of rituximab in patients with myasthenia gravis (Rinomax). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02950155. Updated March 13, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02950155

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Patient Characteristics: Therapy-Refractory Group