Abstract

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is proposed to regulate cerebral blood flow (CBF); however, accurate regional contributions of COX are relatively unknown at baseline and particularly during hypoxia. We hypothesized that COX contributes to both basal and hypoxic cerebral vasodilation, but COX-mediated vasodilation is greater in the posterior versus anterior cerebral circulation. CBF was measured in 9 healthy adults (28 ± 4 yr) during normoxia and isocapnic hypoxia (fraction of inspired oxygen = 0.11), with COX inhibition (oral indomethacin, 100mg) or placebo. Four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging measured cross-sectional area (CSA) and blood velocity to quantify CBF in 11 cerebral arteries. Cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) was calculated (CVC = CBF × 100/mean arterial blood pressure) and hypoxic reactivity was expressed as absolute and relative change in CVC [ΔCVC/Δ pulse oximetry oxygen saturation ()]. At normoxic baseline, indomethacin reduced CVC by 44 ± 5% (P < 0.001) and artery CSA (P < 0.001), which was similar across arteries. Hypoxia ( 80%–83%) increased CVC (P < 0.01), reflected as a similar relative increase in reactivity (% ΔCVC/−Δ) across arteries (P < 0.05), in part because of increases in CSA (P < 0.05). Indomethacin did not alter ΔCVC or ΔCVC/Δ to hypoxia. These findings indicate that 1) COX contributes, in a largely uniform fashion, to cerebrovascular tone during normoxia and 2) COX is not obligatory for hypoxic vasodilation in any regions supplied by large extracranial or intracranial arteries.

Keywords: brain blood flow, low oxygen, MRI, phase contrast, regional CBF

INTRODUCTION

The human brain is highly oxidative, requiring ~20% of whole body oxygen consumption despite only accounting for ~2% of total body mass (44). Cerebral blood flow (CBF) must be highly regulated and responsive to a wide range of environmental and metabolic perturbations to maintain oxygen delivery. For example, exposure to reduced oxygen (isocapnic hypoxia) elicits a robust increase in CBF through vasodilation (4, 6, 27). Despite the importance of controlling CBF, relatively little is known about brain region-specific regulation of CBF.

Some, but not all, human studies indicate a nonuniform increase in CBF during hypoxia (27, 33, 49). The vertebral artery (VA) for instance, demonstrates a ~50% greater relative increase in CBF compared with the internal carotid artery (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA), and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) (49). Similarly, there is a disproportionate increase in hypothalamic and cerebellar flow during hypoxia when compared with cortical brain regions (6). It is postulated that vertebral and basilar arteries are more sensitive to hypoxia than anterior brain regions (27, 49), as they supply the posterior brain regions, including the brainstem and cardiorespiratory centers. Conversely, greater hypoxia-mediated increases in macrovascular flow (21), arterial cross-sectional area (CSA) (22), and microvascular perfusion in the anterior brain circulation have also been observed (24). Further complicating matters, other studies suggest that there may not be regional differences in macrovascular flow (17, 18, 22, 33) or microvascular perfusion (9, 34, 35) during hypoxia. The discrepancies in these findings are likely due to varying severities and durations of hypoxia, fluctuations in arterial CO2 levels, and different measurement techniques [i.e., transcranial Doppler ultrasound vs. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)].

Regardless of whether hypoxic cerebral vasodilation varies by brain region, the mechanisms mediating vasodilation may display specificity. Cyclooxygenase (COX) contributes significantly to basal CBF (2, 15, 17, 38, 39); however, the majority of studies have focused solely on the MCA, leaving regional differences in the contribution of COX unexplored. In addition to basal CBF regulation, animal studies suggest that COX mediates hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (8, 11), whereas human data remain equivocal (10, 15, 17, 38, 39). To our knowledge, only one human study has investigated the region-specific contribution to COX to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (17). In this study, COX inhibition reduced absolute vascular reactivity in the MCA and VA but not in the ICA and PCA. In contrast, other investigators report that COX does not mediate hypoxic vasodilation in the MCA (10, 15, 38, 39). These conflicting data regarding the MCA may be due primarily to methodological differences. For example, transcranial Doppler ultrasound does not directly quantify CBF because it cannot account for changes in artery CSA. Considered collectively, there has yet to be a comprehensive study examining the contribution of COX during normoxia and hypoxia in multiple anterior and posterior arteries.

Recent advances in medical imaging, specifically four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging (4D flow MRI), allow for direct and simultaneous measurement of blood flow and CSA in multiple intracranial arteries (22, 42). Therefore, the purpose of our study was to quantify CBF in 11 major cerebral arteries that comprise the anterior and posterior macrovascular circulations with 4D flow MRI during normoxia and isocapnic hypoxia under placebo and COX-inhibited conditions. These data will provide fundamental insight into cerebral blood regulation in humans, specifically region-specific basal and hypoxia-mediated vasodilation, which may help identify novel therapeutic targets aimed at preventing or reducing the impact of cerebrovascular disease. With this in mind, we hypothesized that COX contributes to both basal CBF and hypoxic cerebral vasodilation and that the contribution of COX would be greater in the posterior compared with anterior cerebral circulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

A total of 9 young, healthy volunteers participated in the study (28 ± 4 yr). Control hypoxia data were previously reported in a larger group of 12 subjects (22). All subjects were nonobese (23 ± 1 kg/m2), nonsmoking, free of overt disease, and not currently taking medication with the exception of birth control, as determined by a health history questionnaire. Women were not pregnant (urinary pregnancy test) and were studied either during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (cycle days 1–5) or low-hormone phase of birth control (self-report). Subjects were instructed to report to the laboratory on all study days having abstained from exercise, alcohol, caffeine, supplements, over the counter medications, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for ≥24 h and having fasted for ≥ 4 h. The nature, purpose, and risks of the study were provided to each subject before written informed consent was obtained. All protocols were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board.

Screening visit.

To determine eligibility, Subjects performed an initial screening visit that included a healthy history and physical activity questionnaire. Height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index (in kg/m2). Waist and hip circumference were measured as indicators of regional adiposity. Brachial artery blood pressure was measured to exclude hypertension. Venous blood samples were obtained for the determination of glucose and lipids (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| n | 9 (5 Male, 4 Female) |

| Age, yr | 28 ± 4 |

| Height, cm | 174 ± 7 |

| Weight, kg | 70 ± 8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23 ± 1 |

| Waist, cm | 81 ± 6 |

| Hip, cm | 98 ± 4 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 72 ± 7 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 155 ± 34 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 57 ± 14 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 89 ± 45 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 88 ± 52 |

| SBP, mmHg | 119 ± 5 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74 ± 6 |

| MABP, mmHg | 89 ± 5 |

| Physical activity, kcal/wk | 2,287 ± 1,858 |

| Indomethacin dose, mg/kg | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

Values are means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, Low density lipoprotein; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Experimental protocol.

Subjects completed two study visits in a randomized, counter-balanced, double-blinded, placebo-controlled design. Placebo and COX inhibition (indomethacin) visits consisted of oral ingestion of either placebo or the nonselective COX inhibitor indomethacin (100 mg) as well as 20 mL of antacid (Maalox) on both study days to prevent gastrointestinal discomfort occasionally associated with oral indomethacin. Our absolute (100 mg) and calculated relative dose (1.4 ± 0.2 mg/kg) of indomethacin are greater than (19, 46) or similar to (10, 17) those previously published. Additionally, in a prior study in our laboratory, an absolute dose of indomethacin (100 mg) resulted in a large decrease in circulating COX metabolites (15). Subjects then rested quietly for 90 min outside of the MRI scanner to allow indomethacin to take effect (15).

After 90 min of quiet rest, subjects entered the MRI scanner and were instrumented for continuous measurement of pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (; pulse oximeter), heart rate (pulse oximeter), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) (Medrad Veris MR Vital Signs Patient Monitor, Bayer Healthcare, Whippany, NJ). Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP; automated sphygmomanometery) was measured before and after each scan. After instrumentation, a normoxia baseline scan was taken (phase-contrast vastly undersampled isotropic projection reconstruction (PC VIPR) scanning sequence, ~5 min), followed by a transition to steady-state hypoxia (<5 min), and the hypoxia MRI scan was taken upon reaching steady-state hypoxia (PC VIPR scanning sequence, ~5 min). The rationale for this protocol was that we wanted to be consistent with prior hypoxic cerebral blood flow studies conducted in our laboratory that aimed at elucidating mechanisms of cerebral blood flow regulation (13, 15, 22, 38, 39). Longer durations or more severe levels of hypoxia (i.e., >30 min) may elucidate alternative mechanisms of cerebral blood flow regulation (27, 49). Furthermore, we aimed to limit subject discomfort, as we have demonstrated that 5 min of steady-state hypoxia elicits a similar cerebral blood flow response compared with 15 min of steady-state hypoxia (14).

Hypoxia.

Isocapnic hypoxia was introduced by having subjects inspire through a two-way non-rebreathing valve (2630 Series, Hans Rudolph Incorporated, Shawnee, KS) supplied by a medical-grade pressurized gas mixture containing 11% O2 and the balance N2 (Airgas, Madison, WI). This gas mixture was expected to elicit an of ~80% based on previous studies in the laboratory (13, 15, 38, 39). This severity of hypoxia is known to elicit an increase in cerebral blood flow and can be tolerated well by human subjects (13, 15, 38, 39, 51). Additionally, this is a physiologically relevant stimulus that is experienced during sojourns to high-altitude environments and in medical conditions such as sleep apnea.

Isocapnia was achieved by titrating medical-grade pressurized CO2 (100% CO2; Airgas) with the hypoxic gas mixture accordingly. ETCO2 was used as a surrogate for arterial CO2 levels (32, 37). Steady-state and ETCO2 were reached in <5 min (no change in and ETCO2 for > 1 min), after which 4D flow MRI scan commenced.

Four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging (PC VIPR).

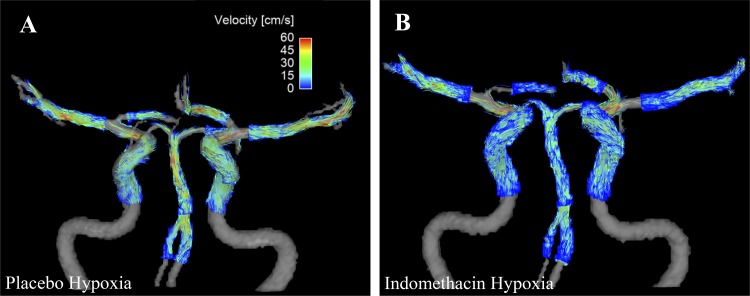

We utilized phase-contrast vastly under sampled isotropic projection reconstruction (PC VIPR) as our 4D flow MRI sequence to quantify blood flow concurrently in 11 separate cerebral arteries (Fig. 1). PC VIPR has been validated and is known to provide accurate blood flow measures within cerebral arteries and in different vascular territories (12, 48). All study imaging was completed with a 3T MRI (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using an eight-channel head coil. The following scan parameters were utilized: imaging volume = 22 × 22 × 22 mL (0.69 mm3 acquired isotropic resolution), scan time = 5 min 30 s, velocity encoding = 100 cm/s, flip angle = 20°, and TR/TE = 6.7/2.8 ms (20 reconstructed cardiac time frames using retrospective cardiac gating and temporal view sharing) (30).

Fig. 1.

Representative angiograms with velocity overlay acquired with four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging during hypoxia with and without indomethacin. A: coronal view, placebo hypoxia. B: coronal view, indomethacin hypoxia.

Data processing.

Data processing was completed using an in-house graphical user interface developed in commercial software (MATLAB, Mathworks, Natick, MA) that is an objective and reliable assessment of cerebral artery blood flow parameters (42). Vessel position was selected with a centerline-processing scheme that utilizes an algorithm to segment individual vessels in a plane perpendicular to the vessel path [one voxel in width (0.69 mm)], simultaneously providing time-averaged velocity, cross-sectional area (CSA), and flow measures. Velocity, CSA, and blood flow were averaged over five consecutive cross sections (5 × 0.69 mm = 3.45 mm), producing a 3.45 mm long segment in each artery of interest (42). Eleven arteries of interest were assessed, including left and right vertebral arteries (VA-L and VA-R, respectively), basilar artery (BA), left and right posterior cerebral arteries (PCA-L and PCA-R, respectively), left and right internal carotid arteries (ICA-L and ICA-R, respectively), left and right middle cerebral arteries (MCA-L and MCA-R, respectively), and left and right anterior cerebral arteries (ACA-L and ACA-R, respectively). For consistent data analyses, individual vessel segmentation occurred at precise locations as follows: VA was measured 4–5 mm from the junction with the BA; BA was measured near the junction with the VA; PCA was measured 4–5 mm from the junction with the BA; ICA was measured in the straight portion of the C4 segment (5); and ACA and MCA were measured 4–5 mm from their junctions with the ICA (A1 and M1, respectively). Total CBF was calculated as the sum of the ICA-L, ICA-R, and BA. Total anterior CBF was calculated at the sum of the ICA-L and ICA-R, whereas the BA was used to represent total posterior CBF.

In 4 of 9 subjects, all 11 cerebral vessels of interest were visible with and without indomethacin during baseline and hypoxia conditions. For the remaining 5 subjects, 1 or more of the 11 cerebral vessels were not visible for the following reasons. One subject had a fetal type PCA-R (originating from the ICA-R) and anatomically did not have a VA-R, whereas a second subject was anatomically missing a VA-L. These are common anatomical variants that can be found in up to one-third of humans (43). Methodologically, indomethacin substantially decreased basal CBF below the detectable limit of PC VIPR scan parameters. Thus, in a third subject, the ACA-L VA-L, PCA-L, and PCA-R were not detectable during indomethacin baseline; in a fourth subject, the PCA-R was not detectible during indomethacin baseline; and in a fifth subject, the ACA-L was not detectable during indomethacin baseline, and in this same subject, the PCA-L was also not detectable during indomethacin baseline and indomethacin hypoxia. Considering that in all cases but one, hypoxia increased flow with indomethacin above detectable limits, these values were included in the flow analysis. However, given that indomethacin baseline data were missing in these cases, we were unable to calculate changes in CBF, CVC, or vascular reactivity in those specific vessels. See Table 2 for number of vessels for each given condition.

Table 2.

Number of vessels analyzed for each condition

| ICA |

MCA |

ACA |

VA |

PCA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | BA | Left | Right | |

| Placebo baseline | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Placebo hypoxia | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Indo baseline | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Indo hypoxia | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

When analyzing changes in cerebrovascular variables during hypoxia with indomethacin, the lowest number within a vessel represents the number of vessels analyzed within that vessel. ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; VA, vertebral artery.

Statistics.

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The main outcome variables were the CBF responses to indomethacin during normoxia and the CBF responses during hypoxia with and without indomethacin. To account for potential differences and individual variation in blood pressure, cerebrovascular conductance was calculated and presented (CVC = [CBF × 100/MABP], mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1). To assess the vessel and region-specific contribution of COX to basal CVC, data were expressed as percent change in CVC (%ΔCVC) from baseline. To assess hypoxic vasodilation comprehensively and interpret the results conservatively, we assessed data in three different expressions: 1) as absolute increase in CVC from normoxia (ΔCVC), 2) as hypoxic reactivity in ΔCVC per unit change in pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (), and 3) as %ΔCVC from baseline, which accounts for large differences in baseline flow associated with artery (i.e., comparing ICA to BA) or indomethacin, which greatly reduces baseline CBF and CVC. This third form of data expression is useful, as %ΔCVC is considered an accurate representation of changes in vascular tone between conditions that vary widely in flow (7, 23, 31), as any given % change in CVC reflects a similar % change in vascular radius.

Minitab 16 (State College, PA) was used for statistical analysis. Significance of systemic hemodynamics variables in response to condition (normoxia or hypoxia) and treatment (placebo or indomethacin) were determined with a general linear model ANOVA.

To explore the role of COX in a region-specific manner, we calculated total CBF (sum of ICA-R, ICA-L, and BA), anterior CBF (sum of ICA-R and ICA-L), and posterior CBF (BA). Significance of the basal effect of indomethacin on total and regional CVC was determined with two-sample t tests, and one-sample t tests were used to determine if basal changes in CVC with indomethacin were less than zero. Significance of the basal effect of indomethacin on vessel-specific CVC was determined by general linear model ANOVA.

Significance of treatment (placebo or COX inhibition) on hypoxia-mediated increases on total CVC was determined with two-sample t tests. Significance of drug (placebo or indomethacin) and region (anterior or posterior) on hypoxia-mediated increases in CVC were determined by general linear model ANOVA.

To explore the region-specific contribution of COX, significance of treatment (placebo or indomethacin) and vessel (VA-R, VA-L, BA, PCA-R, PCA-L, ICA-R, ICA-L, MCA-R, MCA-L, ACA-R, ACA-L) on hypoxia-mediated increases in CVC were determined by general linear model ANOVA. To explore region-specific contribution of COX, significance of treatment (placebo or indomethacin), vessel (VA-R, VA-L, BA, PCA-R, PCA-L, ICA-R, ICA-L, MCA-R, MCA-L, ACA-R, ACA-L), and condition (normoxia or hypoxia) on blood flow, we determined CVC, CSA, vessel diameter, mean velocity, and max velocity by a general linear model ANOVA. Pairwise comparisons were determined with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

RESULTS

Subjects.

Subjects were young, normal weight, healthy, and free of disease (Table 1). All subjects completed both study visits. The placebo control data were previously published with a slightly larger group size (n = 12), which focused on comparing regional responses to hypoxic vasodilation (22).

Systemic hemodynamic responses.

By design, hypoxia reduced by ~18% compared with normoxia (main effect, P < 0.001), and this reduction was not different between placebo and indomethacin conditions (P = 0.14). Heart rate was higher during hypoxia (main effect, P < 0.001) but was lower with indomethacin compared with placebo (main effect, P = 0.02). ETCO2 was stable during all trials, as there was no difference between hypoxia and normoxia (P = 0.18) nor treatment (indomethacin vs. placebo; P = 0.98). Systolic blood pressure (condition, P = 0.72: treatment, P = 0.63), diastolic blood pressure (condition, P = 0.53; treatment, P = 0.51), MABP (condition, P = 0.57; treatment, P = 0.52), and respiratory rate (condition, P = 0.51; treatment, P = 0.36) did not differ by condition or treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Systemic hemodynamic responses

| Placebo |

Indomethacin |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Hypoxia | Baseline | Hypoxia | |

| Heart rate, beats/min §* | 66 ± 9 | 82 ± 8 | 58 ± 8 | 75 ± 11 |

| SBP, mmHg | 130 ± 12 | 131 ± 10 | 128 ± 9 | 129 ± 9 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80 ± 10 | 84 ± 10 | 80 ± 9 | 80 ± 9 |

| MABP, mmHg | 97 ± 10 | 100 ± 10 | 96 ± 9 | 96 ± 8 |

| , % § | 98 ± 1 | 80 ± 4 | 97 ± 1 | 83 ± 4 |

| ETCO2, mmHg | 41 ± 2 | 39 ± 3 | 40 ± 3 | 39 ± 3 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 13 ± 4 | 15 ± 4 | 14 ± 3 | 15 ± 4 |

Values are presented as means ± SD. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ETCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; , pulse oximetry oxygen saturation.

Main effect of condition;

Main effect of pill; P < 0.05.

Effects of indomethacin on basal CBF.

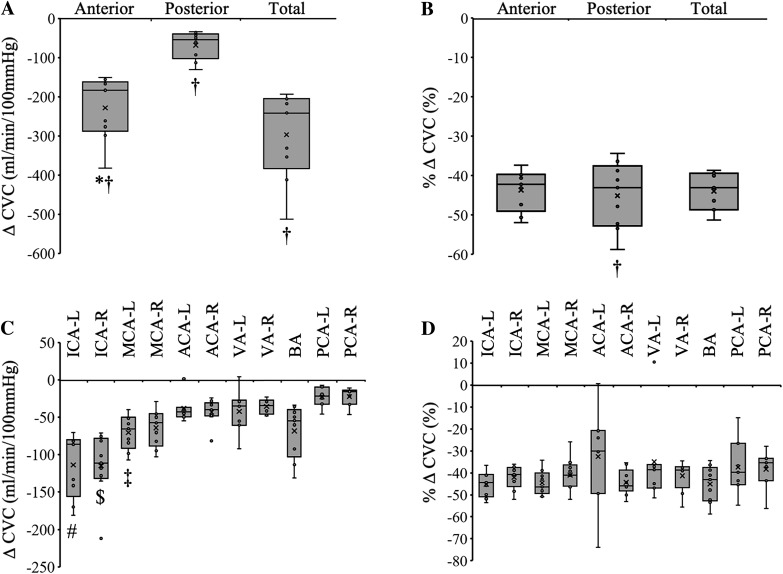

Indomethacin decreased total basal CVC 44 ± 5% (Fig. 2B) from 663 ± 191 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1 to 367 ± 84 mL·min−1·100 mmHg (Fig. 2A; P < 0.001). Anterior CVC was reduced from 518 ± 146 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1 to 290 ± 73 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1 (Fig. 2A; P < 0.001, 44 ± 5% reduction), and posterior CVC was reduced from 145 ± 53 to 77 ± 20 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1 (Fig. 2, A and B; P < 0.001, 45 ± 8% reduction). The relative decrease in CVC was not different between vessels (Fig. 2D; P = 0.54). Conclusions were the same when data were expressed as flow (mL/min).

Fig. 2.

Basal reductions in cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) with indomethacin. A: indomethacin decreased absolute CVC, and this was greater in the anterior circulation compared with posterior circulation. B: indomethacin decreased relative CVC ~45%, and this was similar between anterior and posterior circulations. C: the absolute decrease in CVC with indomethacin was greatest in both internal carotid arteries. D: the relative decrease in CVC with indomethacin was similar across all vessels. †Different from zero. *Anterior vs. posterior. #Vs. all other vessels except the right internal carotid artery (ICA-R) and left middle cerebral artery (MCA-L). $Vs. all other vessels except the left internal carotid artery (ICA-L). ‡Vs. the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA-L) and right posterior cerebral artery (PCA-R). P < 0.001. ACA-L, left anterior cerebral artery; ACA-R, right anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; ICA-L, left internal carotid artery; MCA-R, right middle cerebral artery; VA-L, left vertebral artery; VA-R, right vertebral artery. Small circles, individual data points. X, data mean. Bottom line and top line of box plots represent 1st and 3rd quartiles, and the midline represents the median. Ends of whiskers (excluding outliers) represent maximum and minimum values.

Indomethacin decreased vessel CSA (Table 4; main effect, P < 0.001). The relative decrease in CSA of both ICAs following COX inhibition was greater than that of the PCA-L and VA-R but was similar across all other vessels (Table 4; P = 0.004).

Table 4.

Vessel-specific cerebrovascular responses to hypoxia with and without indomethacin

| ICA |

MCA |

ACA |

VA |

PCA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | BA | Left | Right | |

| Flow, mL/min†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 236 ± 64 | 254 ± 49 | 147 ± 28 | 145 ± 31 | 69 ± 39 | 92 ± 25 | 89 ± 42 | 83 ± 20 | 137 ± 41 | 53 ± 12 | 51 ± 12 |

| Hypoxia | 280 ± 80 | 306 ± 76 | 178 ± 39 | 178 ± 55 | 87 ± 52 | 113 ± 34 | 105 ± 50 | 98 ± 26 | 162 ± 60 | 63 ± 17 | 62 ± 15 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 129 ± 38 | 146 ± 27 | 81 ± 15 | 84 ± 17 | 46 ± 24 | 51 ± 15 | 58 ± 18 | 48 ± 14 | 73 ± 17 | 34 ± 6 | 32 ± 6 |

| Hypoxia | 166 ± 43 | 186 ± 44 | 108 ± 21 | 106 ± 21 | 51 ± 25 | 69 ± 16 | 63 ± 26 | 57 ± 17 | 94 ± 19 | 35 ± 5 | 37 ± 6 |

| ΔFlow, mL/min†* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 44 ± 27 | 53 ± 34 | 31 ± 21 | 34 ± 27 | 18 ± 15 | 21 ± 14 | 16 ± 11 | 15 ± 11 | 25 ± 23 | 10 ± 8 | 11 ± 6 |

| Indo | 37 ± 10 | 40 ± 23 | 27 ± 14 | 21 ± 12 | 9 ± 5 | 18 ± 5 | 11 ± 11 | 9 ± 7 | 21 ± 11 | 1 ± 6 | 6 ± 2 |

| %ΔFlow†* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 18 ± 10 | 20 ± 10 | 21 ± 13 | 22 ± 13 | 25 ± 10 | 22 ± 13 | 19 ± 7 | 19 ± 15 | 17 ± 12 | 19 ± 14 | 22 ± 12 |

| Indo | 30 ± 8 | 27 ± 13 | 34 ± 18 | 26 ± 19 | 21 ± 9 | 39 ± 16 | 20 ± 17 | 19 ± 12 | 31 ± 20 | 6 ± 19 | 20 ± 7 |

| Flow reactivity (Δflow/Δ)† | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| Indo | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| % Flow reactivity (%Δflow/Δ)†*‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| Indo | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 0.3 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| CVC, 100 mL·min−1·mmHg−1†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 249 ± 79 | 270 ± 80 | 155 ± 38 | 153 ± 42 | 72 ± 41 | 97 ± 34 | 95 ± 50 | 85 ± 20 | 145 ± 53 | 56 ± 16 | 53 ± 15 |

| Hypoxia | 286 ± 99 | 314 ± 104 | 182 ± 53 | 183 ± 67 | 88 ± 54 | 115 ± 41 | 109 ± 57 | 97 ± 24 | 166 ± 72 | 64 ± 21 | 63 ± 18 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 135 ± 41 | 155 ± 41 | 85 ± 16 | 89 ± 21 | 47 ± 24 | 54 ± 19 | 61 ± 20 | 50 ± 14 | 77 ± 20 | 35 ± 8 | 33 ± 6 |

| Hypoxia | 173 ± 43 | 196 ± 58 | 112 ± 22 | 110 ± 22 | 52 ± 24 | 73 ± 22 | 65 ± 26 | 60 ± 18 | 99 ± 24 | 36 ± 6 | 39 ± 6 |

| ΔCVC† | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 38 ± 29 | 44 ± 33 | 27 ± 22 | 30 ± 27 | 16 ± 15 | 18 ± 14 | 14 ± 9 | 12 ± 11 | 21 ± 23 | 9 ± 8 | 10 ± 5 |

| Indo | 38 ± 12 | 41 ± 27 | 27 ± 14 | 21 ± 13 | 9 ± 5 | 19 ± 7 | 10 ± 11 | 10 ± 6 | 22 ± 12 | 1 ± 8 | 7 ± 3 |

| %ΔCVC* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 15 ± 10 | 16 ± 11 | 17 ± 12 | 18 ± 12 | 21 ± 10 | 18 ± 12 | 16 ± 7 | 14 ± 15 | 13 ± 11 | 15 ± 13 | 18 ± 11 |

| Indo | 30 ± 11 | 27 ± 16 | 33 ± 17 | 26 ± 19 | 22 ± 13 | 39 ± 17 | 18 ± 17 | 19 ± 10 | 30 ± 18 | 7 ± 26 | 22 ± 11 |

| CVC reactivity (ΔCVC/Δ)† | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Indo | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 0.0 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| % CVC reactivity (%ΔCVC/Δ)†*‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.7 |

| Indo | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| CSA, mm2†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 16.6 ± 5.2 | 17.6 ± 5.0 | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 7.8 ± 2.2 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Hypoxia | 17.4 ± 5.4 | 18.3 ± 5.6 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 2.5 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.9 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 11.8 ± 3.7 | 12.7 ± 3.1 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 1.3 |

| Hypoxia | 13.2 ± 3.9 | 14.0 ± 3.8 | 6.6 ± 2.4 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 2.4 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.6 |

| ΔCSA, mm2* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.4 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Indo | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.6 |

| %ΔCSA* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 5 ± 7 | 4 ± 7 | 9 ± 15 | 10 ± 17 | 6 ± 22 | 13 ± 27 | 5 ± 6 | 4 ± 8 | 6 ± 5 | 5 ± 13 | 4 ± 12 |

| Indo | 11 ± 3 | 10 ± 6 | 21 ± 34 | 13 ± 23 | 19 ± 21 | 27 ± 33 | 18 ± 23 | 8 ± 18 | 8 ± 13 | 2 ± 15 | 14 ± 19 |

| Diameter, mm†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| Hypoxia | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Hypoxia | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| ΔDiameter, mm* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± .1 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.1 |

| Indo | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| % ΔDiameter* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 2 ± 4 | 2 ± 3 | 4 ± 7 | 4 ± 8 | 3 ± 10 | 6 ± 12 | 3 ± 3 | 2 ± 4 | 3 ± 3 | 2 ± 6 | 2 ± 6 |

| Indo | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 3 | 9 ± 14 | 6 ± 10 | 9 ± 9 | 12 ± 13 | 8 ± 10 | 4 ± 8 | 4 ± 6 | 1 ± 7 | 7 ± 8 |

| Mean velocity, cm/s†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 26 ± 6 | 26 ± 3 | 40 ± 5 | 41 ± 5 | 26 ± 8 | 32 ± 6 | 27 ± 7 | 25 ± 3 | 31 ± 5 | 23 ± 2 | 22 ± 3 |

| Hypoxia | 29 ± 7 | 30 ± 5 | 45 ± 6 | 46 ± 7 | 29 ± 6 | 36 ± 10 | 30 ± 8 | 28 ± 4 | 34 ± 6 | 26 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 20 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 19 ± 6 | 21 ± 4 | 19 ± 3 | 16 ± 4 | 20 ± 4 | 16 ± 3 | 16 ± 3 |

| Hypoxia | 23 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 | 30 ± 6 | 31 ± 7 | 19 ± 6 | 23 ± 6 | 19 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 | 25 ± 6 | 16 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 |

| ΔMean velocity, cm/s* | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 3 ± 3 | 4 ± 3 | 5 ± 7 | 5 ± 6 | 4 ± 4 | 4 ± 6 | 3 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 4 ± 3 |

| Indo | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 4 ± 5 | 4 ± 6 | 1 ± 3 | 3 ± 3 | 1 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | 4 ± 4 | 1 ± 4 | 1 ± 3 |

| % ΔMean velocity | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 13 ± 9 | 16 ± 11 | 13 ± 17 | 12 ± 14 | 19 ± 19 | 11 ± 17 | 13 ± 9 | 13 ± 8 | 10 ± 8 | 14 ± 11 | 19 ± 14 |

| Indo | 17 ± 7 | 16 ± 10 | 15 ± 22 | 15 ± 25 | 4 ± 15 | 12 ± 16 | 2 ± 9 | 11 ± 13 | 22 ± 22 | 5 ± 22 | 8 ± 20 |

| Max velocity, cm/s†*§‡ | |||||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 58 ± 11 | 62 ± 7 | 89 ± 10 | 88 ± 9 | 70 ± 10 | 79 ± 11 | 65 ± 13 | 61 ± 6 | 71 ± 8 | 63 ± 12 | 61 ± 12 |

| Hypoxia | 65 ± 9 | 72 ± 8 | 93 ± 10 | 99 ± 13 | 78 ± 10 | 81 ± 15 | 72 ± 13 | 67 ± 8 | 77 ± 8 | 68 ± 8 | 72 ± 7 |

| Indo | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 51 ± 9 | 58 ± 5 | 64 ± 10 | 65 ± 6 | 53 ± 9 | 61 ± 12 | 55 ± 9 | 49 ± 12 | 58 ± 9 | 49 ± 8 | 50 ± 11 |

| Hypoxia | 55 ± 8 | 65 ± 8 | 76 ± 13 | 78 ± 14 | 63 ± 20 | 68 ± 10 | 60 ± 11 | 50 ± 16 | 65 ± 13 | 55 ± 7 | 58 ± 14 |

| ΔMax velocity, cm/s | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 7 ± 8 | 10 ± 10 | 4 ± 9 | 11 ± 10 | 8 ± 11 | 2 ± 7 | 7 ± 6 | 5 ± 3 | 6 ± 7 | 4 ± 8 | 11 ± 11 |

| Indo | 4 ± 7 | 7 ± 12 | 11 ± 9 | 13 ± 13 | 6 ± 13 | 7 ± 11 | 6 ± 8 | 1 ± 8 | 8 ± 14 | 5 ± 11 | 8 ± 15 |

| % ΔMax velocity | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 14 ± 16 | 17 ± 17 | 6 ± 11 | 12 ± 11 | 14 ± 18 | 2 ± 8 | 12 ± 9 | 9 ± 5 | 9 ± 11 | 9 ± 13 | 22 ± 21 |

| Indo | 10 ± 15 | 13 ± 20 | 18 ± 13 | 19 ± 21 | 9 ± 22 | 15 ± 21 | 11 ± 14 | 2 ± 15 | 15 ± 26 | 13 ± 26 | 18 ± 30 |

Values are presented as means ± SD. ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; CSA, cross-sectional area; CVC, cerebral vascular conductance; ICA, internal carotid artery; Indo, indomethacin; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; VA, vertebral artery.

Main effect of vessel;

Main effect of pill;

Main effect of condition;

Vessel × pill interaction; P < 0.05.

Indomethacin reduced mean blood velocity (Table 4; main effect, P < 0.001). The relative decrease in vessel mean velocity following indomethacin was greater in the VA-R compared with ICA-R but was not different across all other vessels (Table 4; P = 0.03).

Hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

Hypoxia increased CVC (Table 4; P < 0.01). The relative increase in CVC (%ΔCVC) was similar between vessels (P = 0.97) and regions (P = 0.23). Expressing data as flow yielded similar conclusions. Hypoxia-mediated changes in relative vessel CSA (P = 0.96) and relative mean velocity (P = 0.91) were also not different between vessels.

Total and regional contribution of COX to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

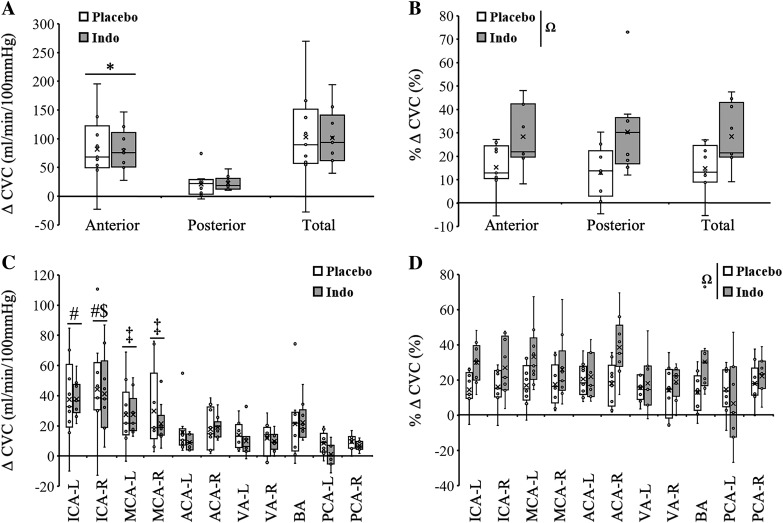

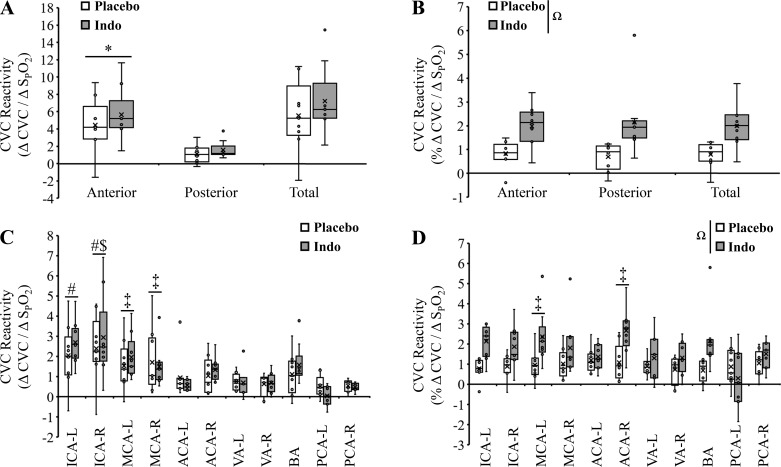

To explore the role of COX in a region-specific manner, we calculated total CBF (ICAs + BA), anterior CBF (ICAs only), and posterior CBF (BA only). The absolute increase in total CVC during hypoxia was not different between placebo and indomethacin (Fig. 3A; 103 ± 83 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1 vs. 101 ± 50 mL·min−1·100 mmHg−1; P = 0.35). Similarly, absolute total CVC reactivity was not different between placebo and indomethacin (Fig. 4A; 5.6 ± 4.1 vs. 7.2 ± 4.0; ΔCVC/Δ; P = 0.28). In contrast, the relative increase in total CVC during hypoxia was greater with indomethacin (Fig. 3B; 15 ± 10% vs. 28 ± 13%; P = 0.03). Similarly, relative total CVC reactivity was greater following indomethacin (Fig. 4B; 0.8 ± 0.5 vs. 2.0 ± 0.9; %ΔCVC/Δ; P = 0.005). Expressing data as flow yielded similar conclusions with the exception that the greater relative increase in total CBF with indomethacin was not significant (19 ± 10% vs. 29 ± 11%; P = 0.07).

Fig. 3.

Changes in hypoxia-mediated cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) with and without indomethacin (Indo) A: hypoxia-mediated increases in absolute CVC were similar between indomethacin and placebo and greater in the anterior circulation compared with posterior circulation. B: hypoxia-mediated increases in relative CVC were augmented with indomethacin and were similar between anterior posterior circulations. C: hypoxia-mediated increases in absolute CVC were similar between placebo and indomethacin but different between vessels (main effect). D: hypoxia-mediated increases in relative CVC were augmented with indomethacin (main effect) and were similar between vessels. *Anterior vs. posterior. ΩMain effect of pill. #Main effect of vessel vs. anterior cerebral arteries (ACAs), vertebral arteries (VAs), and posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs). $Main effect of vessel vs. basilar artery (BA). ‡Main effect of vessel vs. left PCA (PCA-L). P < 0.05. ACA-L, left ACA; ACA-R, right ACA; ICA-L, left internal carotid artery; ICA-R, right internal carotid artery; MCA-L, left middle cerebral artery; MCA-R, right middle cerebral artery; VA-L, left VA; VA-R, right VA. Small circles, individual data points. X, data mean. Bottom line and top line of box plots represent 1st and 3rd quartiles, and the midline represents the median. Ends of whiskers (excluding outliers) represent maximum and minimum values.

Fig. 4.

Changes in hypoxia-mediated vessel cerebrovascular reactivity with and without indomethacin (Indo). A: absolute cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) reactivities were similar between indomethacin and placebo and greater in the anterior circulation compared with posterior circulation. B: relative CVC reactivities were augmented with indomethacin and similar between anterior and posterior circulations. C: absolute CVC reactivities were similar between placebo and indomethacin but were different between vessels (main effect). D: relative CVC reactivities were augmented with indomethacin (main effect) and were different between vessels (main effect). *Anterior vs. posterior. ΩMain effect of pill. main effect of vessel: #Main effect of vessel vs. anterior cerebral arteries (ACAs), vertebral arteries (VAs), and posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs). $Main effect of vessel vs. basilar artery (BA). ‡Main effect of vessel vs. left PCA (PCA-L). P < 0.05. ACA-L, left ACA; ACA-R, right ACA; ICA-L, left internal carotid artery; ICA-R, right internal carotid artery; MCA-L, left middle cerebral artery; MCA-R, right middle cerebral artery; VA-L, left VA; VA-R, right VA. Small circles, individual data points. X, data mean. Bottom line and top line of box plots represent 1st and 3rd quartiles, and the midline represents the median. Ends of whiskers (excluding outliers) represent maximum and minimum values.

The hypoxia-mediated change in absolute CVC was greater in the anterior compared with posterior circulation (Fig. 3A, main effect, P < 0.001) but was unaffected by COX inhibition (P = 0.94). Likewise, absolute hypoxic CVC reactivity was greater in the anterior compared with posterior circulation (Fig. 4A, main effect, P < 0.001) but was unaffected by COX inhibition (P = 0.28). In contrast, the hypoxia-mediated change in relative CVC was greater with indomethacin (Fig. 3B; main effect, P = 0.002) and not different between regions (P = 0.97). Likewise, relative hypoxic CVC reactivity was greater with indomethacin (Fig. 4B; main effect, P < 0.001) and not different between regions (P = 0.96). Expressing data as flow (Table 4) yielded the same conclusions.

Vessel-specific contribution of COX to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

The hypoxia-mediated increase in absolute CVC was not different between placebo and indomethacin (Fig. 3C, Table 4; P = 0.25). However, the hypoxia-mediated increase in absolute CVC was greater in both ICAs compared with ACAs, VAs, and PCAs; greater in the ICA-R compared with BA; and greater in both MCAs compared with PCA-L (Fig. 3C, Table 4; main effect, P < 0.001). Similarly, absolute CVC reactivity was not different between placebo and indomethacin (Fig. 4C, Table 4; P = 0.47). The hypoxia-mediated increase in absolute CVC reactivity was also greater in both ICAs compared with ACAs, VAs, and PCAs; greater in the ICA-R compared with BA; and greater in both MCAs compared with PCA-L (Fig. 4C, Table 4; main effect, P < 0.001).

In contrast to absolute change and reactivity data, the hypoxia-mediated increase in relative CVC was greater with indomethacin (main effect, P < 0.001) and was similar between all vessels (Fig. 3D, Table 4; P = 0.06). The relative CVC reactivity was also greater with indomethacin (main effect, P < 0.001) but was greater in MCA-L and ACA-R compared with PCA-L (Fig. 4D; main effect, P = 0.02).

Expressing data as flow yielded similar conclusions with the exception that the hypoxia-mediated increase in relative flow was greater in the ACA-R compared with the PCA-L (Table 4; main effect, P = 0.03)

Vessel CSA was greater during hypoxia compared with normoxia (Table 4; main effect, P = 0.01) and was reduced following indomethacin compared with placebo (Table 4; main effect, P < 0.001). The hypoxia-mediated changes in absolute and relative vessel CSA were greater with indomethacin compared with placebo (main effect, P = 0.04, P = 0.01) but not different between vessels (Table 4; P = 0.23, P = 0.33). Additional cerebrovascular responses to hypoxia and indomethacin are presented in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this investigation was to examine the region-specific contribution of COX to basal CBF and to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation. We concurrently quantified CBF and CSA in 11 major cerebral arteries during normoxia and isocapnic hypoxia, with and without COX inhibition. This systematic approach led to several novel findings: 1) indomethacin decreased basal normoxic CVC in a fairly uniform fashion (44 ± 5%) across 11 cerebral arteries because of reductions in both blood velocity and CSA, 2) indomethacin did not reduce hypoxia-mediated vasodilation when analyzed as ΔCVC or absolute reactivity (ΔCVC/Δ), and 3) the impact of indomethacin is not region specific. These data are contrary to our hypotheses, yet they provide novel insight into region-specific basal and hypoxia-mediated vasodilation.

Basal effects of indomethacin.

Indomethacin substantially decreased basal CVC uniformly across the cerebral circulation (44 ± 5%). This reduction is markedly larger than what has been observed by the majority of earlier studies, most likely because of a lack of accounting for decreases in basal CSA with indomethacin. Previous investigations utilizing Doppler methodology report a range of indomethacin-mediated reductions in basal middle cerebral artery blood velocity (MCAv) from 25%–41% (3, 10, 15–17, 19, 26). In the current investigation, MCAv was reduced by 35 ± 7% (Table 4), which agrees with these prior velocity measures. Furthermore, the present data show indomethacin decreases cerebral artery CSA (Table 4). Therefore, most investigations relying solely on MCAv have likely underestimated the contribution of COX to the maintenance of basal vascular tone. Disease states that differentially effect the role of COX on CSA and/or velocity might be particularly difficult to interpret without the use of MRI approaches.

Literature comparing the regional impact of COX on basal CBF regulation is sparse. In a recent thorough study utilizing duplex ultrasound (17), indomethacin decreased basal blood flow in both the ICA and VA by ~32%, which is less than the 44 ± 6% and 39 ± 13%, respectively, shown in the current study. Possible explanations for this discrepancy include differing measurement methodology (ultrasound vs. 4D flow MRI) and slight differences in indomethacin dosing. The present data confirm the impact of indomethacin on reducing blood velocity and add new information on reducing CSA. Taken together, these data offer comprehensive insight in the contribution of COX as a robust and important vasodilator mechanism to target when combating conditions in which baseline CBF declines, such as healthy aging (2).

Hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

Data comparing region-specific, hypoxic cerebral vasodilation are inconclusive. Some studies suggest the posterior circulation demonstrates greater sensitivity to hypoxia compared with the anterior circulation (4, 6, 27, 33, 49). Conversely, there are equally compelling observations of greater hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in the anterior circulation (21, 24) as well as uniform cerebral vasodilation during hypoxia (9, 17, 18, 22, 33–35).

In the current investigation, we examined CBF responses to hypoxia in multiple anterior and posterior arteries while maintaining ETCO2 to prevent hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia. This is especially important when investigating region-specific hypoxic vasodilation, as cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity has been shown to be region specific (20, 41, 45). Our data demonstrate that there are no regional differences in hypoxic cerebral vasodilation at moderate hypoxia ( ~81%), which agrees with prior findings (9, 17, 18, 22, 33–35). Thus, if there are regional differences in hypoxic cerebral vasodilation, they may only be evident during more severe levels of hypoxia (i.e., = 70%) (49) or during poikilocapnic hypoxia (6).

Contribution of COX to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

To our knowledge, there is only human study that has proposed vessel-specific differences in the contribution to COX to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (17). In this study, COX was shown to mediate hypoxic vasodilation in both the MCA and VA but not in the ICA or PCA (17). With this as rationale, we hypothesized that COX-mediated hypoxic cerebral vasodilation would be region specific in the remaining cerebral arteries that have not been studied. Contrary to our hypothesis, we demonstrate that COX fails to contribute to hypoxic vasodilation, and this observation was similar across brain regions. Additionally, expressing data as %ΔCVC supports the concept that COX is not obligatory for hypoxic vasodilation.

In vivo animal data indicate no contribution of COX during severe hypoxia (8, 25, 40), whereas in vitro data suggest a substantial contribution of COX (11). Likewise, human data are equivocal. Investigations in young, healthy adults suggest that COX may mediate hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (17), whereas others suggest no role of COX in mediating hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (10, 15, 38, 39). However, most human studies are limited in that they only measured CBF velocity in a single cerebral vessel (MCA) and therefore cannot provide insight into any potential contributions of COX to region-specific vascular control.

To compound the technical challenges in comparing vascular responses between brain regions, there are widely varying blood flows through the different cerebral arteries, and indomethacin mediates a substantial reduction in basal CBF (Table 4). These limitations have led to a variety of different data expressions and interpretations that have potentially added to misunderstanding in the literature. When investigating the effects of COX inhibition on hypoxic vasodilation across different regions of the cerebral circulation, expressing the data as relative reactivity (%ΔCVC/ΔSpO2) may be the most appropriate form of data expression, as %ΔCVC reflects changes in vascular tone between conditions that vary widely in blood flow (7, 23, 31). Along these lines, Hoiland et al. (17) concluded that COX exhibited regional specificity within the brain via an observed reduction in absolute, but not relative, reactivity with indomethacin in the MCA and VA at an of ~80%.

To address some limitations of studies primarily using transcranial Doppler ultrasound, our study utilized 4D flow MRI as a methodology to evaluate COX-mediated hypoxic vasodilation simultaneously in multiple cerebral arteries. The advantage of 4D flow MRI is the ability to objectively quantify CSA, and therefore blood flow, rather than blood velocity, which is an index of flow. Interpretation of blood velocity data alone do not account for potential hypoxia or indomethacin-mediated changes in macrovessel CSA at the measurement sites (Table 4), therefore hindering interpretation and insight into mechanistic cerebrovascular regulation. When an MRI approach is used, along with controlling ETCO2, our results clearly indicate that COX is not obligatory for hypoxic vasodilation at a level of hypoxia eliciting an of ~80%.

Differential contribution of cyclooxygenase at baseline versus hypoxia.

COX appears to contribute robustly to the maintenance of basal vascular tone in healthy adults, but it is not obligatory for hypoxic cerebral vasodilation. The simplest explanation for these differing roles is that COX products contribute to the maintenance of basal vascular tone, but they do not contribute to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation. A second possibility is that at rest in normoxic conditions, COX production of the vasodilatory prostaglandin PGI2 (prostacyclin), is greater than vasoconstrictor prostaglandin thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (36). During hypoxia, COX signaling may shift to support either a greater production of TXA2 or reduced production of PGI2 or a combination of the two. Third is the idea that COX inhibition removes simultaneously suppression of the hypoxic vasodilator nitric oxide. In humans, nitric oxide has been shown to potentially mediate hypoxic cerebral vasodilation (47). Interestingly, COX inhibition increases the synthesis of nitric oxide in isolated human saphenous veins (1), and COX restrains the nitric oxide portion of β-adrenergic receptor-mediated vasodilation in the peripheral circulation of humans (29). Thus, inhibition of COX may be “masked” by simultaneously removing suppression of additional vasodilator mechanisms such as nitric oxide Although the current study design did not explore these possibilities, future investigations targeted at these explanations may provide additional insight.

Alternative data expression.

Expressing data as absolute changes in CVC of CBF (i.e., ΔCVC),or changes relative to hypoxia (i.e., ΔCVC/%Δ) indicates there is no effect of COX inhibition on hypoxic cerebral vasodilation. A close comparison of flow and conductance values, with a dramatic decrease in basal flow with indomethacin, led us to express data in relative terms (%ΔCVC/%Δ) as the most appropriate manner to assess downstream vasodilation or vasoconstriction to isocapnic hypoxia within our study design (7, 23, 31). The inherent differences between the vessels examined before any experimental manipulation (i.e., larger basal CSA and flow in ICAs vs. PCAs) support comparison of relative values. For example, a vessel with a smaller flow or initial CSA would have to vasodilate or vasoconstrict to a greater amount from its initial CSA to achieve an equal absolute change in flow or conductance of a larger vessel. When taken in total, using any of the three manners of data expression, present data do not support an obligatory role for COX in mediating hypoxic vasodilation.

Experimental considerations.

We quantified CBF concurrently in 11 cerebral arteries utilizing a double-blind, randomized, counter-balanced, placebo-controlled design under tightly controlled experimental conditions to gain insight into COX regulation of isocapnic-hypoxic cerebrovascular vasodilation in humans. In light of these strengths, there are some limitations worthy of consideration. First, in 5 subjects, at least 1 of the 11 cerebral vessels was not detected because of anatomical variance or sensitivity limitations of MRI to low flow (see materials and methods). Of particular interest are the data from the two participants with anatomical variants (see materials and methods). It is unknown whether these anatomical differences impact hypoxic reactivity (%ΔCVC). When excluding their data from analysis of preindomethacin and postindomethacin conditions, results and conclusions are unchanged (data not shown), but we hesitate to speculate on the true impact of these anatomical variances. Despite limitations, we were able to collect a complete data set (n = 9) on five cerebral arteries, including ICAs, MCAs, and BA. This is a more thorough investigation than has been conducted to date. In the remaining six arteries (right and left PCAs, ACAs, and VAs), we analyzed a minimum of seven subjects for each vessel, which has provided valuable information pertaining to the region-specific role of COX in the maintenance of basal CBF as well as hypoxia-mediated increases in CBF.

Interestingly, indomethacin augmented the relative increase in CVC as well as the relative increase in CSA. However, given the longer temporal resolution of MRI technology, we were unable to determine if the augmented change in vessel CSA was due to the direct effects of indomethacin on the microvasculature or elevations in shear stress from downstream vasodilation.

Finally, we utilized an absolute dose of indomethacin and did not measure the concentration of plasma COX metabolites to demonstrate adequate COX inhibition. An identical dose previously utilized in our laboratory demonstrated a substantial reduction in circulating COX metabolites (15). Furthermore, our absolute dose (100 mg) and calculated relative dose (1.4 ± 0.1 mg/kg) of indomethacin is greater than (19, 46) or similar to (10, 17) those previously published. Considering the dosage and drastic decrease in CBF with indomethacin, we are confident we robustly inhibited COX. However, without cerebral concentrations of COX metabolites, data may somewhat underestimate the contribution of COX to basal and hypoxic CBF regulation.

Perspectives and Significance

The novel findings of the study are as follows: 1) indomethacin decreased basal CVC robustly and similarly across the cerebral circulation, 2) indomethacin reduced basal CSA across intracranial and extracranial arteries, and 3) hypoxia-mediated increases in absolute CVC and reactivity are similar across brain regions and not altered by indomethacin. Thus, we conclude that COX mediates a large portion of baseline perfusion throughout intracranial and extracranial arteries, which aids in understanding mechanisms of reduced CBF across numerous clinical conditions. However, contrary to our hypotheses, in healthy adults, COX is not obligatory for moderate hypoxic cerebral vasodilation, suggesting that the mechanisms regulating basal CBF differ substantially from regulation during stress. These data provide fundamental insight into cerebral blood regulation in humans, specifically into differences between region-specific basal and hypoxia-mediated vasodilation. These findings contribute to the integrated understanding of CBF control, which will help lead to therapeutic targets aimed at preventing or reducing the impact of cerebrovascular disease.

GRANTS

Funding for this project was provided by the American Diabetes Association (1-12-IN-39) and the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant UL1TR000427. J. M. Kellawan was supported by the American Heart Association (15POST23100020). We thank the Marsh Center for Exercise and Movement Research for the generous support of this work.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. conceived and designed research; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. performed experiments; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. analyzed data; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. interpreted results of experiments; G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., and W.G.S. prepared figures; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., and W.G.S. drafted manuscript; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.K., G.L.P., J.W.H., A.R.-A., O.W., and W.G.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the study participants. We also thank Cameron Rousseau, Sara John, and Jenelle Fuller for assistance with data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker JE, Bakhle YS, Anderson J, Treasure T, Piper PJ. Reciprocal inhibition of nitric oxide and prostacyclin synthesis in human saphenous vein. Br J Pharmacol 118: 643–648, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes JN, Schmidt JE, Nicholson WT, Joyner MJ. Cyclooxygenase inhibition abolishes age-related differences in cerebral vasodilator responses to hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1884–1890, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes JN, Taylor JL, Kluck BN, Johnson CP, Joyner MJ. Cerebrovascular reactivity is associated with maximal aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 114: 1383–1387, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01258.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binks AP, Cunningham VJ, Adams L, Banzett RB. Gray matter blood flow change is unevenly distributed during moderate isocapnic hypoxia in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 104: 212–217, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00069.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouthillier A, van Loveren HR, Keller JT. Segments of the internal carotid artery: a new classification. Neurosurgery 38: 425–432, 1996. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck A, Schirlo C, Jasinsky V, Weber B, Burger C, von Schulthess GK, Koller EA, Pavlicek V. Changes of cerebral blood flow during short-term exposure to normobaric hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18: 906–910, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199808000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckwalter JB, Clifford PS. The paradox of sympathetic vasoconstriction in exercising skeletal muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 29: 159–163, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyle MG, Oh W, Stonestreet BS. Effects of indomethacin on brain blood flow and cerebral metabolism in hypoxic newborn piglets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H141–H149, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyer EA, Hopkins SR, Perthen JE, Buxton RB, Dubowitz DJ. Regional cerebral blood flow during acute hypoxia in individuals susceptible to acute mountain sickness. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 160: 267–276, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan JL, Burgess KR, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJ, Lucas RA, Cotter JD, Ainslie PN. Influence of indomethacin on the ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypoxia. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 601–610, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredricks KT, Liu Y, Rusch NJ, Lombard JH. Role of endothelium and arterial K+ channels in mediating hypoxic dilation of middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physio Heart Circ Physioll 267: H580–H586, 1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.2.H580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu T, Korosec FR, Block WF, Fain SB, Turk Q, Lum D, Zhou Y, Grist TM, Haughton V, Mistretta CA. PC VIPR: a high-speed 3D phase-contrast method for flow quantification and high-resolution angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26: 743–749, 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell JW, Morgan BJ, Schrage WG. Impaired hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in younger adults with metabolic syndrome. Diab Vasc Dis Res 10: 135–142, 2013. doi: 10.1177/1479164112448875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell JW, Peltonen GL, Schrage WG. Reactive oxygen species and cyclooxygenase products explain the majority of hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in healthy humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 226: e13288, 2019. doi: 10.1111/apha.13288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrell JW, Schrage WG. Cyclooxygenase-derived vasoconstriction restrains hypoxia-mediated cerebral vasodilation in young adults with metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H261–H269, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00709.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley GL, Watson CL, Ainslie PN, Tokuno CD, Greenway MJ, Gabriel DA, O’Leary DD, Cheung SS. Corticospinal excitability is associated with hypocapnia but not changes in cerebral blood flow. J Physiol 594: 3423–3437, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoiland RL, Ainslie PN, Wildfong KW, Smith KJ, Bain AR, Willie CK, Foster G, Monteleone B, Day TA. Indomethacin-induced impairment of regional cerebrovascular reactivity: implications for respiratory control. J Physiol 593: 1291–1306, 2015. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.284521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoiland RL, Bain AR, Tymko MM, Rieger MG, Howe CA, Willie CK, Hansen AB, Flück D, Wildfong KW, Stembridge M, Subedi P, Anholm J, Ainslie PN. Adenosine receptor-dependent signaling is not obligatory for normobaric and hypobaric hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 122: 795–808, 2017. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00840.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoiland RL, Tymko MM, Bain AR, Wildfong KW, Monteleone B, Ainslie PN. Carbon dioxide-mediated vasomotion of extra-cranial cerebral arteries in humans: a role for prostaglandins? J Physiol 594: 3463–3481, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP272012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Yokoyama I, Iida H, Kinoshita T, Hatazawa J, Shimosegawa E, Okudera T, Kanno I. Regional differences in cerebral vascular response to PaCO2 changes in humans measured by positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20: 1264–1270, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200008000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen GF, Kagenaar DA, Basnyat B, Odoom JA. Basilar artery blood flow velocity and the ventilatory response to acute hypoxia in mountaineers. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 133: 65–74, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9048(02)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellawan MJ, Harrell JW, Roldan-Alzate A, Wieben O, Schrage WG. Regional hypoxic cerebral vasodilation facilitated by diameter changes primarily in anterior versus posterior circulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37: 2025–2034, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16659497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lautt WW. Resistance or conductance for expression of arterial vascular tone. Microvasc Res 37: 230–236, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawley JS, Macdonald JH, Oliver SJ, Mullins PG. Unexpected reductions in regional cerebral perfusion during prolonged hypoxia. J Physiol 595: 935–947, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP272557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Cerebral arteriolar dilation to hypoxia: role of prostanoids. Am J Physiol 272: H418–H424, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis NC, Bain AR, MacLeod DB, Wildfong KW, Smith KJ, Willie CK, Sanders ML, Numan T, Morrison SA, Foster GE, Stewart JM, Ainslie PN. Impact of hypocapnia and cerebral perfusion on orthostatic tolerance. J Physiol 592: 5203–5219, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.280586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis NC, Messinger L, Monteleone B, Ainslie PN. Effect of acute hypoxia on regional cerebral blood flow: effect of sympathetic nerve activity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1189–1196, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00114.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limberg JK, Johansson RE, Peltonen GL, Harrell JW, Kellawan JM, Eldridge MW, Sebranek JJ, Schrage WG. β-Adrenergic-mediated vasodilation in young men and women: cyclooxygenase restrains nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H756–H764, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00886.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Redmond MJ, Brodsky EK, Alexander AL, Lu A, Thornton FJ, Schulte MJ, Grist TM, Pipe JG, Block WF. Generation and visualization of four-dimensional MR angiography data using an undersampled 3-D projection trajectory. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 25: 148–157, 2006. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.861706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markwald RR, Kirby BS, Crecelius AR, Carlson RE, Voyles WF, Dinenno FA. Combined inhibition of nitric oxide and vasodilating prostaglandins abolishes forearm vasodilatation to systemic hypoxia in healthy humans. J Physiol 589: 1979–1990, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.205013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McSwain SD, Hamel DS, Smith PB, Gentile MA, Srinivasan S, Meliones JN, Cheifetz IM. End-tidal and arterial carbon dioxide measurements correlate across all levels of physiologic dead space. Respir Care 55: 288–293, 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogoh S, Sato K, Nakahara H, Okazaki K, Subudhi AW, Miyamoto T. Effect of acute hypoxia on blood flow in vertebral and internal carotid arteries. Exp Physiol 98: 692–698, 2013. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.068015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagani M, Ansjön R, Lind F, Uusijärvi J, Sumen G, Jonsson C, Salmaso D, Jacobsson H, Larsson SA. Effects of acute hypobaric hypoxia on regional cerebral blood flow distribution: a single photon emission computed tomography study in humans. Acta Physiol Scand 168: 377–383, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagani M, Salmaso D, Sidiras GG, Jonsson C, Jacobsson H, Larsson SA, Lind F. Impact of acute hypobaric hypoxia on blood flow distribution in brain. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 202: 203–209, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearce WJ, Ashwal S, Cuevas J. Direct effects of graded hypoxia on intact and denuded rabbit cranial arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H824–H833, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.3.H824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peebles K, Celi L, McGrattan K, Murrell C, Thomas K, Ainslie PN. Human cerebrovascular and ventilatory CO2 reactivity to end-tidal, arterial and internal jugular vein PCO2. J Physiol 584: 347–357, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peltonen GL, Harrell JW, Aleckson BP, LaPlante KM, Crain MK, Schrage WG. Cerebral blood flow regulation in women across menstrual phase: differential contribution of cyclooxygenase to basal, hypoxic, and hypercapnic vascular tone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R222–R231, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00106.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peltonen GL, Harrell JW, Rousseau CL, Ernst BS, Marino ML, Crain MK, Schrage WG. Cerebrovascular regulation in men and women: stimulus-specific role of cyclooxygenase. Physiol Rep 3: e12451, 2015. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakabe T, Siesjö BK. The effect of indomethacin on the blood flow-metabolism couple in the brain under normal, hypercapnic and hypoxic conditions. Acta Physiol Scand 107: 283–284, 1979. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato K, Sadamoto T, Hirasawa A, Oue A, Subudhi AW, Miyazawa T, Ogoh S. Differential blood flow responses to CO2 in human internal and external carotid and vertebral arteries. J Physiol 590: 3277–3290, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schrauben E, Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Spaak E, Malm J, Wieben O, Eklund A. Fast 4D flow MRI intracranial segmentation and quantification in tortuous arteries. J Magn Reson Imaging 42: 1458–1464, 2015. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaban A, Albright KC, Boehme AK, Martin-Schild S. Circle of Willis variants: fetal PCA. Stroke Res Treat 2013: 1–6, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/105937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skow RJ, MacKay CM, Tymko MM, Willie CK, Smith KJ, Ainslie PN, Day TA. Differential cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity in anterior and posterior cerebral circulations. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 189: 76–86, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smirl JD, Tzeng YC, Monteleone BJ, Ainslie PN. Influence of cerebrovascular resistance on the dynamic relationship between blood pressure and cerebral blood flow in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1614–1622, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01266.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Mil AH, Spilt A, Van Buchem MA, Bollen EL, Teppema L, Westendorp RG, Blauw GJ. Nitric oxide mediates hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 92: 962–966, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Birgander R, Wieben O, Johnson KM, Malm J, Eklund A. Measuring pulsatile flow in cerebral arteries using 4D phase-contrast MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 34: 1740–1745, 2013. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willie CK, Macleod DB, Shaw AD, Smith KJ, Tzeng YC, Eves ND, Ikeda K, Graham J, Lewis NC, Day TA, Ainslie PN. Regional brain blood flow in man during acute changes in arterial blood gases. J Physiol 590: 3261–3275, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.228551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willie CK, Tzeng YC, Fisher JA, Ainslie PN. Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J Physiol 592: 841–859, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]