Abstract

Background

Chronic plaque psoriasis is an immune‐mediated, chronic, inflammatory skin disease, which can impair quality of life and social interaction. Disease severity can be classified by the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score ranging from 0 to 72 points. Indoor artificial salt bath with or without artificial ultraviolet B (UVB) light is used to treat psoriasis, simulating sea bathing and sunlight exposure; however, the evidence base needs clear evaluation.

Objectives

To assess the effects of indoor (artificial) salt water baths followed by exposure to artificial UVB for treating chronic plaque psoriasis in adults.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to June 2019: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and LILACS. We also searched five trial registers, and checked the reference lists of included studies, recent reviews, and relevant papers for further references to relevant trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of salt bath indoors followed by exposure to artificial UVB in adults who have been diagnosed with chronic plaque type psoriasis. We included studies reporting between‐participant data and within‐participant data. We evaluated two different comparisons: 1) salt bath + UVB versus other treatment without UVB; eligible comparators were exposure to psoralen bath, psoralen bath + artificial ultraviolet A UVA) light, topical treatment, systemic treatment, or placebo, and 2) salt bath + UVB versus other treatment + UVB or UVB only; eligible comparators were exposure to bath containing other compositions or concentrations + UVB or UVB only.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

The primary efficacy outcome was PASI‐75, to detect people with a 75% or more reduction in PASI score from baseline. The primary adverse outcome was treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal. For the dichotomous variables PASI‐75 and treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal, we estimated the proportion of events among the assessed participants.

The secondary outcomes were health‐related quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, (DLQI) pruritus severity measured using a visual analogue scale, time to relapse, and secondary malignancies.

Main results

We included eight RCTs: six reported between‐participant data (2035 participants; 1908 analysed), and two reported within‐participant data (70 participants, 68 analysed; 140 limbs; 136 analysed). One study reported data for the comparison salt bath with UVB versus other treatment without UVB; and eight studies reported data for salt bath with UVB versus other treatment with UVB or UVB only. Of these eight studies, only five reported any of our pre‐specified outcomes and assessed the comparison of salt bath with UVB versus UVB only. The one included trial that assessed salt bath plus UVB versus other treatment without UVB (psoralen bath + UVA) did not report any of our primary outcomes. The mean age of the participants ranged from 41 to 50 years of age in 75% of the studies. None of the included studies reported on the predefined secondary outcomes of this review. We judged seven of the eight studies as at high risk of bias in at least one domain, most commonly performance bias. Total trial duration ranged between at least two months and up to 13 months.

In five studies, the median participant PASI score at baseline ranged from 15 to 18 and was balanced between treatment arms. Three studies did not report PASI score. Most studies were conducted in Germany; all were set in Europe. Half of the studies were multi‐centred (set in spa centres or outpatient clinics); half were set in a single centre in either an unspecified settings, a psoriasis daycare centre, or a spa centre. Commercial spa or salt companies sponsored three of eight studies, health insurance companies funded another, the association of dermatologists funded another, and three did not report on funding.

When comparing salt bath plus UVB versus UVB only, two between‐participant studies found that salt bath plus UVB may improve psoriasis when measured using PASI 75 (achieving a 75% or more reduction in PASI score from baseline) (risk ratio (RR) 1.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.24 to 2.35; 278 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Assessment was conducted at the end of treatment, which was equivalent to six to eight weeks after start of treatment. The two trials which contributed data for the primary efficacy outcome were conducted by the same group, and did not blind outcome assessors. The German Spas Association funded one of the trials and the funding source was not stated for the other trial.

Two other between‐participant studies found salt bath plus UVB may make little to no difference to outcome treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal compared with UVB only (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.64; 404 participants; low‐certainty evidence). One of the studies reported adverse events, but did not specify the type of events; the other study reported skin irritation. One within‐participant study found similar results, with one participant reporting severe itch immediately after Dead Sea salt soak in the salt bath and UVB group and two instances of inadequate response to phototherapy and conversion to psoralen bath + UVA reported in the UVB only group (low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Salt bath with artificial ultraviolet B (UVB) light may improve psoriasis in people with chronic plaque psoriasis compared with UVB light treatment alone, and there may be no difference in the occurrence of treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal. Both results are based on data from a limited number of studies, which provided low‐certainty evidence, so we cannot draw any clear conclusions.

The reporting of our pre‐specified outcomes was either non‐existent or limited, with a maximum of two studies reporting a given outcome.

The same group conducted the two trials which contributed data for the primary efficacy outcome, and the German Spas Association funded one of these trials. We recommend further RCTs that assess PASI‐75, with detailed reporting of the outcome and time point, as well as treatment‐related adverse events. Risk of bias was an issue; future studies should ensure blinding of outcome assessors and full reporting.

Plain language summary

Indoor bathing in salt water followed by exposure to artificial ultraviolet B light for chronic plaque psoriasis

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of indoor bathing in salt water for adults with chronic plaque psoriasis followed by artificial ultraviolet B (UVB) light treatment. We evaluated two different comparisons: 1) Salt bath with UVB versus other treatment without UVB; eligible comparators were exposure to psoralen bath, psoralen bath + artificial ultraviolet A (UVA) light, topical treatment, systemic treatment (oral or injected medicines that work throughout the entire body), or placebo (an inactive substance). 2) Salt bath with UVB versus other treatment with UVB or UVB only; eligible comparators were exposure to bath containing other compositions or concentrations + UVB or UVB only. The degree of severity of psoriasis can be measured by the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI). Improvement can be indicated by a reduction of PASI. We requested at least a 75% reduction in PASI‐75 score to evaluate a potential beneficial effect. To evaluate a potential harmful effect, we chose treatment‐related side effects severe enough to stop treatment.

Background

Chronic plaque psoriasis is a skin disease characterised by red‐coloured lesions with silvery scales. Bathing in the Dead Sea and exposure to the sun may improve the lesions but may not be practical for most patients. Artificial salt bath and exposure to UVB could simulate the natural exposure.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to June 2019. We included eight trials (1976 analysed participants). One included trial assessed salt bath plus UVB versus other treatment without UVB (psoralen bath + UVA), but it did not report our primary outcomes for this comparison. Eight trials assessed our second comparison of interest: salt bath with UVB versus other treatment with UVB or UVB only, and those that reported any outcomes of interest (only five studies) specifically compared salt bath with UVB versus UVB only.

No study reported our secondary outcomes. The duration of trials in total ranged between at least two months and up to 13 months. Outcomes were assessed at the end of treatment.

We analysed trials in which different treatments were applied to different participants, and we separately analysed trials in which different treatments were applied to the same participant, but to different body parts. Participants were male or female, and their ages mostly ranged from 41 to 50 years. In five studies, the median PASI score at baseline ranged from 15 to 18 and was balanced between treatment arms. Three studies did not report PASI score. Three studies were sponsored by commercial spa or salt companies, one by health insurance companies, one by an association of dermatologists, and three did not report on funding. Half of the studies were conducted in multiple centres; the remainder were conducted in single centres. Most of the studies were conducted in Germany; all were based in Europe.

Key results

No study reported primary outcome data for the comparison salt bath with UVB versus other treatment without UVB; five studies reported primary outcome data for salt bath with UVB versus UVB only. With respect to achieving PASI‐75, the pooled data of two studies indicated that salt bath + UVB may reduce psoriasis severity compared to UVB only (low‐certainty evidence); however, these two studies were conducted by the same group, and the German Spas Association funded one of the trials (the other trial did not report any funding source). Neither of the studies hid the treatment allocation from the outcome assessors.

When assessing treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal, data from three other studies showed there may be little to no difference between salt bath plus UVB and the comparator UVB only (low‐certainty evidence). The adverse events included skin irritation and severe itch immediately after Dead Sea salt soaks (salt bath + UVB group), and inadequate response to phototherapy and conversion to psoralen bath + UVA (UVB only group).

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the evidence for ‘PASI‐75’ and ‘treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal’ as low certainty. Our confidence was affected by limitations, such as risk of bias (examples being inadequate blinding and high probability of publication bias). The reporting of our outcomes was non‐existent or limited.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Salt bath + UVB compared with UVB alone for chronic plaque psoriasis.

| Salt bath + UVB compared with UVB alone for chronic plaque psoriasis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with chronic plaque psoriasis Setting: indoor clinic or spa Intervention: salt bath + UVB Comparison: UVB alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI)* | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed riskc | Corresponding risk | |||||

| PASI‐75 (number of participants with event) 6 to 8 weeks after start of treatment | Study population | RR 1.71 (1.24 to 2.35) |

278 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa | The event was defined as achieving a 75% or more reduction in PASI score from baseline. | |

| 285 per 1000 | 487 per 1000 (353 to 669) |

|||||

| Treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal (number of participants withdrawing) 3 to 8 weeks after the start of treatmentd | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.35 to 2.64) | 404 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb | The event was defined as dropping out of the study because of treatment‐related complications. | |

| 35 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (12 to 92) |

|||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

a We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels for this outcome. We downgraded one level because of study limitations (risk of bias). Due to lack of blinding, we judged a high bias of performance bias. We downgraded one level because of high probability of publication bias. The only two between‐participant studies that did contribute data on salt bath + UVB versus UVB alone (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b) to this outcome were conducted by the same sponsor.

b We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels for this outcome. We downgraded one level because of study limitations (risk of bias). Due to lack of blinding, we judged a high risk of performance bias. We downgraded one level because of high probability of publication bias. There were only two between‐participant studies (Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001) that contributed data on salt bath + UVB versus UVB alone to this outcome.

c The assumed risk is based on the mean number of events across the control groups. Calculation regarding PASI‐75 response: Number of events: 22 + 14 = 36, total number of participants: 66 + 60 = 126, risk per 1000: 36 / 126 * 1000 = 285.

d Two between‐participant studies (Klein 2011, Leaute‐Labreze 2001) reported seven events with salt bath + UVB and seven events with UVB only. One additional within‐participant study (Dawe 2005) reported one event with salt bath + UVB and two events with UVB only.

Background

Description of the condition

Prevalence

Psoriasis is a multifactorial, immune‐mediated chronic inflammatory skin disease (Nestle 2009), affecting roughly 2% of the world population (Christophers 2001). In population‐based surveys, the prevalence of psoriasis is 2.2% in the continental USA (Stern 2004), and it is 1.5% in the UK (Gelfand 2005). In adults, prevalence ranges from 0.9% to 8.5% and incidence ranges from 78.9 to 230 per 100,000 person‐years on a global scale (Parisi 2013). The occurrence of psoriasis increases with age and with distance of geographic regions from the equator; there is no clear difference in the prevalence between men and women (Parisi 2013).

Clinical signs and course

Clinically, chronic plaque psoriasis, which is also known as psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common type of psoriasis, affecting 80% to 90% of people with psoriasis (Griffiths 2007; Lebwohl 2003). It is characterised by easily defined red‐coloured lesions (Nestle 2009). The plaques are a result of an inflammatory and hyperproliferative (growing faster than usual) epidermis (Nestle 2009). They are typically found on the outer sides of the elbow and knee joints as well as on the scalp and back. A genetic predisposition may be the most important basis for an onset of psoriasis (Nestle 2009). A dysregulated immune system may explain the pathogenesis of inflammation and keratinocyte activation and proliferation (Nestle 2009). The disease severity can change with time, sometimes with long periods of calm and sometimes with severe exacerbation (Parisi 2013), with or without recognised trigger factors, such as infection and other environmental factors as referred to in section 'Risk factors' in Description of the condition. The extent of the affected body surface area may be used to classify the severity as mild (less than 5%), moderate (5% to 10%), or severe (greater than 10%) (Menter 2007). Henseler suggested two forms of nonpustular psoriasis: the early onset form was associated with familial inheritance, and the late onset form occurred predominantly sporadically (Henseler 1985).

Symptoms

The main symptoms are itching and pain associated with uncomfortable scaling as a result of loss of cells from the epidermal layer of the skin (Martin 2015).

Diagnosis

A medical doctor can suspect the diagnosis on the appearance of the skin and a dermatologist may confirm the diagnosis. Scaly and erythematous plaques that may be painful and itching are typical skin characteristics (Nestle 2009). A skin biopsy may be helpful to clarify the clinical diagnosis.

Prognosis

The majority of patients experience mild skin lesions (Nestle 2009). Severe lesions may impair quality of life and social interaction.

Severity indices

Physician‐reported severity indices

Fredriksson 1978 developed the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). It is a measure of average redness, thickness, and scaliness of skin lesions weighted by the area of involvement. Table 2 displays characteristics of the PASI. Response to therapy may be assessed by the percentage of people who have achieved a 75% or more reduction in their PASI score from baseline, which is referred to as PASI‐75. Itching is a substantial symptom of psoriasis, which may be assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 ('no itching') to 100 ('severe itching') as proposed by Zhu 2014.

1. Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI).

| Section | Area involved | Severity | ||||

| Item | Factor | Item | Factor | Item | Clinical signs | Factor |

| Head | 0.1 | ‐ | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 | Sum of clinical signs | ‐ | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, or 12 |

| ‐ | ‐ | 0% | 0 | ‐ | Erythema (redness) | 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 |

| ‐ | ‐ | < 10% | 1 | ‐ | Induration (thickness) | 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 |

| ‐ | ‐ | 10% to < 30% | 2 | ‐ | Desquamation (scaling) | 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 |

| ‐ | ‐ | 30% to < 50% | 3 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ‐ | ‐ | 50% to < 70% | 4 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ‐ | ‐ | 70% to < 90% | 5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ‐ | ‐ | 90% to 100% | 6 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Arms | 0.2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Trunk | 0.3 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Legs | 0.4 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Subtotal | Section factor *area factor* sum of clinical signs factor | |||||

| Total | Sum of subtotals; range 0 to 72 | |||||

According to Fredriksson 1978. Online calculator available (Corti 2009). Instructions: multiply section factor with area involved factor and multiply with sum of clinical signs factor; repeat for all four sections and add up all four subtotals. The items and corresponding factors regarding the area involved and the severity are exemplified for the section item 'head' and are not shown for the other section items 'arms', 'trunk', and 'legs'. Severity of clinical signs range from none (zero) to maximum (four).

Patient‐reported severity indices

Finlay 1994 developed the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The following website provides further information and interpretation: www.dermatology.org.uk. The aim of this questionnaire is to measure how much the skin problem of a person has affected his or her life over the previous week (see Table 3).

2. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire.

| Number | Question | Answer options |

| 1 | Over the last week, how itchy, sore, painful, or stinging has your skin been? | Very much A lot A little Not at all |

| 2 | Over the last week, how embarrassed or self‐conscious have you been because of your skin? | Very much A lot A little Not at all |

| 3 | Over the last week, how much has your skin interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 4 | Over the last week, how much has your skin influenced the clothes you wear? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 5 | Over the last week, how much has your skin affected any social or leisure activities? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 6 | Over the last week, how much has your skin made it difficult for you to do any sport? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 7 | Over the last week, has your skin prevented you from working or studying? (If "No", over the last week, how much has your skin been a problem at work or studying?) |

Yes No Not relevant |

| 8 | Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 9 | Over the last week, how much has your skin caused any sexual difficulties? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

| 10 | Over the last week, how much of a problem has the treatment for your skin been, for example, by making your home messy or by taking up time? | Very much A lot A little Not at all Not relevant |

The aim of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire is to measure how much the life of adults has been affected by their skin problem over the last week. The DLQI is calculated by summing the score of each question, resulting in a maximum of 30 and a minimum of zero. The higher the score, the more quality of life is impaired. The scoring of each question is as follows: Very much (three), A lot (two), A little (one), Not at all (zero), Not relevant (zero); question seven = Yes (three) to unanswered (zero).

Meaning of the total DLQI score: zero to one = no effect at all on patient's life; two to five = small effect on patient's life; six to 10 = moderate effect on patient's life; 11 to 20 = very large effect on patient's life; 21 to 30 = extremely large effect on patient's life. Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) of the DLQI: a change in DLQI score of at least four points is considered clinically important (Basra 2008).

Finlay 1994 developed the DLQI. The following website provides further information and interpretation: www.dermatology.org.uk.

Risk factors

The process by which psoriasis arises is not fully understood. Population, family, and twin studies have shown a genetic contribution to psoriasis (Griffiths 2007; Lønnberg 2013; Rahman 2005), which includes the association of psoriasis with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles (Gupta 2014). An allele may be described of either the part of a gene that was inherited from the father, or the other part of a gene that was inherited from the mother. HLA genes encode for certain proteins on the surface of cells that help control the immune system. Currently, it is estimated that genetic data explain only 30% of psoriasis (Barker 2014). Prieto‐Perez 2013 stated that "the many genes associated with psoriasis and the immune response include tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 23, and interleukin 12."

Prieto‐Perez 2013 also referred to the development of new drugs (e.g. etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, secukinumab) that target cytokines (e.g. tumour necrosis factor alpha, p40 subunit of interleukin 23 and interleukin 12) and, as a result, suppress the unwanted dysregulated and more than usual immune response. Bachelez 2013 also addressed the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and stated, for example, that interleukin 36 is strongly elevated in the keratinocytes of psoriatic tissue.

Huerta 2007 conducted a prospective cohort study with nested case‐control analysis, in which a group of people were followed over a period of time. A random sample of controls was matched to people who developed psoriasis by age, sex, and calendar year. Odds ratios were adjusted for age and other risk factors. The study found an association between previous skin disorders, infectious disorders, obesity, and smoking with the onset of psoriasis. The authors did not find an association with other potential risk factors, such as stress, diabetes (high blood sugar), hypertension (high blood pressure), hyperlipidaemia (high blood fat), cardiovascular disease, or rheumatoid arthritis.

Comorbidity

Psoriasis may be associated with other diseases, such as arthritis, depression, inflammatory bowel disease, and cardiovascular diseases (Oliveira 2015). As inflammation is involved in some of the associated diseases, it can be speculated whether these diseases may be connected with psoriasis on the ground of common genetic and immune‐related factors.

Health‐related quality of life

Psoriasis causes considerable psychological disability and has a major impact on a person's quality of life (Rapp 1999). Thus, perception of psychosocial disability and quality of life may be paramount when assessing the importance of the condition to an individual and the subsequent treatment of the disease (Menter 2007). A patient‐reported index of disease severity is described above (DLQI). Wahl interviewed 22 hospitalised patients with psoriasis and found that bodily suffering was a core variable with regard to the patients' experience of living with psoriasis (Wahl 2002). For people with psoriasis, itching is a measure of the effect the disease has on quality of life (Zhu 2014).

Cost

The financial burden on people with this disease and on healthcare providers is considerable and was about 35.2 billion dollars in the USA in 2013 (Vanderpuye‐Orgle 2015). It was estimated that incremental medical costs contributed 34.7%; reduced health‐related quality of life, 33.5%; and productivity losses, 31.8% (Vanderpuye‐Orgle 2015).

Description of the intervention

Salt bath followed by artificial ultraviolet B light was developed to simulate exposure to salt and sunlight delivered during climatotherapy (relocation to a region with a climate more favourable to the outcome) at the Dead Sea (Huang 2018). For example, the whole body is soaked in salt water for 15 to 30 minutes, which may have various concentrations ranging from 1 g to 250 g sodium chloride dissolved in one litre water. The soaking is repeated several times a week for a maximum of 20 to 30 applications within a time period of eight weeks. After bathing, various doses of ultraviolet B (UVB) light are applied to the whole body (Gambichler 2000a). The combination of bathing in salt water with UVB bathing thereafter may be called balneophototherapy (Halverstam 2008). Patients with psoriasis could improve with balneophototherapy (Harari 2007).

Treatments for people with chronic plaque psoriasis include a variety of alternatives such as:

topical therapy including steroidal and non‐steroidal agents;

systemic medications (Sbidian 2017) including various biological drugs (Nunez 2019), and additional investigational agents being studied (Ellis 2019);

phototherapy including UVB irradiation alone without bathing in salt water, and

photochemotherapy including ultraviolet A (UVA) irradiation plus psoralen, a compound that aids the absorption of UVA irradiation by making the skin more susceptible to the effects of light rays.

Ultraviolet radiation and its wavelength is defined by the International Commission on Illumination CIE 2011: "radiation for which the wavelengths are shorter than those for visible radiation; the range between 100 nm and 400 nm is commonly subdivided into: UVA: 315 nm to 400 nm; UVB: 280 nm to 315 nm; and UVC: 100 nm to 280 nm". UVB may be subdivided by some authors in broad band (280 nm to 315 nm), narrow band (311), or selective band (300 nm to 315 nm).

The choice of an appropriate therapy is associated with the grade of severity and may be used as comparators with salt baths.

Topical therapy including steroidal and non‐steroidal agents may be mainly used for mild or localised disease (Lebwohl 2005; Menter 2007).

Systemic medications are mainly used for severe or refractory disease (Lebwohl 2005; Menter 2007), which include various oral agents as well as injectable biological agents.

Phototherapy including UVB irradiation alone without bathing in salt water may be used predominantly for moderate or more extensive disease (Lebwohl 2005; Menter 2007).

Phototherapy and photochemotherapy may be also used for those not responding sufficiently to topical treatment (Singh 2016; van de Kerkhof 2004); psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) light photochemotherapy may be used for moderate or severe disease (Lebwohl 2005; Menter 2007). For people with widespread chronic plaque psoriasis, phototherapy may be regarded as the first‐choice treatment because it may have fewer adverse events than systemic or biological agents (Nguyen 2009). Psoralen is a photosensitising compound that aids the absorption of UVA light and increases the skin's sensitivity to light, but subsequently may have carcinogenic properties (Archier 2012). It is administered either orally, in bath water, as a cream, or as a gel. Thus, PUVA is divided into oral PUVA, bath PUVA, and topical (cream) PUVA (Chen 2013). Momtaz 1998 reported that PUVA photochemotherapy has been used in psoriasis and 23 other skin disorders. The risk of development of squamous cell carcinomas may be high if the patients have received ionising radiation or inorganic arsenic, or if patients require continuous treatment for many years. Melanomas may also develop in a few patients. Stern 1998 warned that the use of PUVA should be weighed against the persistent, dose‐related increase in the risk of squamous cell cancer.

How the intervention might work

Salt bath, with or without phototherapy, is being widely used to treat moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. The mechanism of action of UVB is not completely clear (Weatherhead 2013). UVB phototherapy for treating psoriasis may result in the induction of apoptosis (programmed cell death) of keratinocytes, which are the main cell types in the skin, as well as epidermal and dermal T lymphocytes (cells within the skin that are involved in inflammation) (Weatherhead 2011; Wong 2013). The minimum amount of UVB that produces redness 24 hours after exposure is used as the starting dose for UVB light treatments; this 'minimal erythema dose' decreases after salt water bathing (Gambichler 1998).

There may be increased UV transmission to the skin after soaking in salt water (Gambichler 2011), which may lead to stronger inflammation (e.g. UV‐induced erythema) and also to increased apoptosis of keratinocytes and T lymphocytes, and thus improved clearance of psoriasis (Gambichler 2011; Wong 2013). The mechanism of action of low concentrations of sodium chloride in water used in indoor salt water baths followed by artificial UVB light is unknown. Speculative mechanisms have been proposed, for example, salt solutions might wash out unfavourable substances from the skin lesions, salt water bathing might increase skin sensitivity to UVB light and thereby increasing its action on the lesion, single salt components could act favourably on the cells of the skin lesions, the intervention might inhibit cell proliferation (Schempp 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

Studies suggest that indoor salt water baths with (Brockow 2007), or without exposure to artificial UVB (Schiener 2007), may benefit patients with psoriasis. However, the evidence underlying clinical efficacy, such as longer remission from disease and higher dermatology‐related quality of life, has not yet been clearly evaluated. It should be pointed out that the use of high concentrations of salt is cumbersome due to the large amounts of salt needed. Although indoor salt water baths are widely used in practice to treat chronic plaque psoriasis, no systematic review has been conducted to assess its effectiveness for reducing skin lesions and improving quality of life. Therefore, the aim of this review is to evaluate the efficacy and any severe adverse events of indoor salt water baths by focusing on patient‐centred outcomes. The methods planned for this review were published as a protocol: Indoor salt water baths followed by artificial UVB light for chronic plaque psoriasis (Peinemann 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effects of indoor salt water baths followed by exposure to artificial ultraviolet B (UVB) light for treating chronic plaque psoriasis in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that randomised people or limbs to either the test intervention or a control intervention.

We did not find a reason to exclude right‐left comparative studies. Nevertheless, pretreatment of the skin of a body part investigated in a cross‐over design may influence the results as opposed to no pretreatment. To prevent the concerning additional bias, we excluded cross‐over designs. We suggested that simultaneous application of the intervention of interest on multiple body parts of each participant may distract the scoring of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response and other subjective assessments. We are positive that right‐left comparative study should not include comparing different body parts. Different body parts may be affected differently and the assessment may introduce bias. We did not find a reason to exclude cluster‐randomised trials. Throughout the review, we used the term 'people or limbs' to accommodate people who were randomised, as well as randomised legs, arms, and elbows.

We planned to include the following designs.

Simple parallel group design according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 9.3.1, quote: "participants are individually randomised to one of two intervention groups, and a single measurement for each outcome from each participant is collected and analyzed" (Higgins 2011).

Multiple observations for the same outcome, specifically repeated measurements. If the data were to be included in a meta‐analysis, we planned to select a single time point and to analyse only data at this time point for studies in which it was presented.

Multiple observations for the same outcome, specifically, multiple body parts receive different interventions according to the Handbook section 9.3.8, quote: "These trials have similarities to cross‐over trials: whereas in cross‐over trials individuals receive multiple treatments at different times, in these trials they receive multiple treatments at different sites." (Higgins 2011). In the present review, we considered paired comparisons within participants, such as comparisons of right versus left arm, leg, elbow, or knee. We planned to separately analyse the within‐participant data and the between‐participant data.

Cluster‐randomised trials according to the Cochrane Handbook section 9.3.2, quote: "groups of participants, such as schools or families are randomized to different interventions. [...] Participants within any cluster often tend to respond in a similar manner, and thus their data can no longer be assumed to be independent of one another" (Higgins 2011).

We did not include the following study designs.

Cross‐over design according to the Handbook section 9.3.3, quote: "all participants receive all interventions in sequence: they are randomized to an ordering of interventions, and participants act as their own control.". We expected a high risk of carryover according to the Handbook section 16.4.2, quote: "Carryover is the situation in which the effects of an intervention given in one period persist into a subsequent period, thus interfering with the effects of different subsequent intervention" (Higgins 2011).

Multiple observations for the same outcome, specifically, multiple body parts receive the same intervention according to the Handbook section 9.3.7, quote: "people are randomized, but multiple parts (or sites) of the body receive the same intervention, a separate outcome judgement being made for each body part, and the number of body parts is used as the denominator in the analysis. [...] This is similar to the situation in cluster‐randomized trials, except that participants are the 'clusters" (Higgins 2011).

Comparison of different body parts within participants, such as comparing arm versus leg.

Types of participants

Adults (i.e. 18 years of age or older) of any ethnic background or gender who have been diagnosed with chronic plaque type psoriasis by a dermatologist. We excluded people with pustular psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, or inverse psoriasis.

Types of interventions

The aim of this review was to assess the efficacy of salt bath added to ultraviolet B (UVB) light. We did not seek to assess efficacy of salt bath only.

Comparison 1: salt bath + UVB versus other treatment without UVB

Test intervention

Exposure to indoor salt water bath followed by artificial UVB light for chronic plaque psoriasis. We included studies where bathing in salt water was performed indoors during or prior to exposure to UVB. We excluded studies where bathing in salt water was performed outdoors and for leisure purposes, such as bathing in geothermal sea water, bathing in a thermal lagoon, or bathing in a salty lake.

Control intervention

Exposure to psoralen bath, psoralen bath + artificial ultraviolet A (UVA) light, topical treatment, systemic treatment, or placebo.

Comparison 2: salt bath+ UVB versus other treatment + UVB or UVB only

Test intervention

Exposure to indoor salt water bath followed by artificial UVB for chronic plaque psoriasis. We included studies where bathing in salt water is performed indoors during or prior to exposure to UVB. We excluded studies where bathing in salt water is performed outdoors and for leisure purposes, such as bathing in geothermal sea water, bathing in a thermal lagoon, or bathing in a salty lake.

Control intervention

Exposure to bath containing other compositions or concentrations + UVB or UVB only.

Types of outcome measures

We did not use the outcomes listed here as criteria for including studies; they are the outcomes of interest within studies identified for inclusion.

Primary outcomes

Between‐participant data as well as within‐participant data:

physician‐assessed outcome: psoriasis area and severity index (PASI)‐75;

physician‐assessed outcome: treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal.

Secondary outcomes

Between‐participant as well as within‐participant data:

participant‐reported outcome: dermatology life quality index (DLQI);

participant‐reported outcome: pruritus severity using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 ('no itching') to 100 ('severe itching');

physician‐reported outcome: time to relapse;

physician‐assessed outcome: secondary malignancies.

We did not consider using the Physician Global Assessment (PGA), because we favoured PASI, which is reportedly validated and preferred for use in clinical trials (Robinson 2012).

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist searched the following databases up to 4 June 2019:

the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2019, Issue 6 in the Cochrane Library using the strategy in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 3;

Embase via Ovid (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 4; and

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 5.

Online trials registers

We (FP, SP) searched the following online trials registers up to 6 June 2019 using the term 'psoriasis' in the field 'condition' and 'phototherapy' in the field 'intervention':

the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com) (called 'The metaRegister of Controlled Trials' in the protocol);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (called 'The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register' in the protocol);

the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au);

the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/); and

the EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Searching other resources

References from bibliographies

We checked the bibliographies of included studies, relevant articles, and review articles for further references to relevant trials.

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of the target intervention. However, we examined data on adverse effects from the included studies that we identified.

Data collection and analysis

Some parts of the methods section of this Cochrane Review used text that was originally published in other Cochrane publications co‐authored by FP and protocol contributor Doreen Tushabe (predominantly Peinemann 2013a and Peinemann 2013b), as well as using text that was originally published in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

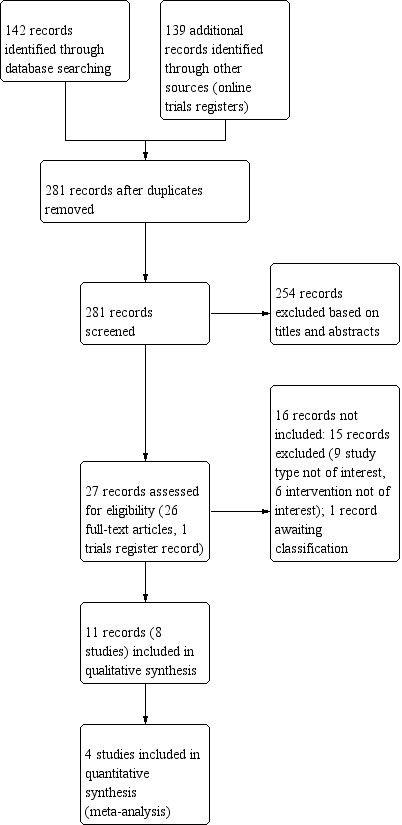

While preparing this systematic review, we endorsed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) statement, adhered to its principles and conformed to its checklist (Moher 2009). We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp 2011), and removed any duplicates. Two review authors (FP, SP) independently examined any remaining references. We included a study selection flow chart in the review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We excluded those studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (FP, SP) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved papers. We resolved any disagreements by discussion between the two review authors; no third party arbitration was necessary. We documented reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. If we identified multiple reports of one study we used the most‐up‐to‐date full‐text results. We checked the multiple reports for possible duplicate data, addressed the issue and did not include duplicate data in the analysis.

Data extraction and management

For each included study, two review authors (FP, SP) extracted study characteristics and outcomes independently onto a data extraction form. The data included: information on study design, participant characteristics (such as inclusion criteria, age, disease severity, comorbidity, previous treatment, number enrolled in each arm), interventions (such as type of irradiation, type of bath, dose applied, duration of therapy, control treatment), risk of bias, follow‐up duration, outcome measures, and deviations from the study protocol. We pilot tested The Cochrane Editorial Resources Committee's data collection form for intervention reviews (for RCTs only) available from the Cochrane Skin Group website: www.skin.cochrane.org/resources, then used this for data extraction. We resolved differences between review authors by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FP, SP) independently appraised the risk of bias in the included studies. We resolved differences between review authors by discussion. We used the items listed within Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011):

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data such as missing data (attrition bias);

selective reporting such as not reporting pre‐specified outcomes (reporting bias); and

other sources of bias such as bias related to the specific study design (other bias).

In general, a judgement of "low risk" of bias was given if plausible bias is unlikely to seriously alter the results, for example, if the participants and investigators enrolling those participants could not foresee the assignment. A judgement of "high risk" of bias was given if plausible bias seriously weakens confidence in the results, for example, if the participants or investigators enrolling those participants could possibly foresee the assignments. A judgement of "unclear" risk of bias was given if plausible bias raises some doubt about the results, for example, the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement.

To draw conclusions about the overall risk of bias for an outcome, it was necessary to summarise the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessments performed for each individual study. We assessed the risk of bias at study level, not by outcome. We aligned the summary assessment to the Cochrane 'Possible approach for summary assessments of the risk of bias for each important outcome (across domains) within and across studies', as shown in Table 8.7a in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed whether the risk of bias for a single outcome was low, unclear, or high, then we interpreted whether the plausible bias was unlikely to seriously alter the results, raises some doubts about the results, or seriously weakened the confidence in the results. We assessed within a study whether there was a low risk of bias for all key domains, an unclear risk of bias for one or more domains, or a high risk of bias for one or more key domains. We assessed across studies whether most information was from studies at low risk of bias or at high or unclear risk of bias, and we assessed across studies whether the proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias was sufficient to affect the interpretation of results.

Measures of treatment effect

For time‐to‐event data such as survival, we planned to extract the hazard ratio (HR) and its standard error or confidence interval (CI) from trial reports; if these were not reported, we planned to estimate the logHR and its standard error using the methods of Parmar 1998 and using the tool provided by Tierney 2007.

For dichotomous data, such as PASI‐75 and treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal, we estimated the proportion of events among the assessed participants. We pooled the data and estimated a risk ratio (RR) and a P value for overall effect by using the Mantel‐Haenszel statistic and a fixed‐effect model. If the P value was not reported by the study, then we estimated the P value by using the web‐based Easy Fisher Exact Test Calculator (Social Science Statistics 2018). In case of rare events, we planned to use Peto odds ratios instead, but this was not applied.

For continuous outcomes (e.g. PASI), we planned to extract the final value or change from baseline and corresponding standard deviation (SD) of the outcome of interest and the number of people or limbs assessed at endpoint in each treatment arm at the end of follow‐up. This was in order to estimate the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) between treatment arms. We planned to analyse and present continuous data using the MD if all results were measured on the same scale (e.g. PASI). If this was not the case (e.g. fear, or quality of life), we planned to use the SMD. Eligible continuous outcomes were not reported.

We planned to extract the proportion of participants who reached the 50% reduction of the respective psoriatic lesion score compared to the baseline value at a fixed time point to allow pooling of data. If this was not possible, we planned to extract the time necessary to reach 50% reduction compared to baseline value. To calculate a mean difference, the number of people at risk and the probability of an event at a given time is required. Where studies did not provide that information, we chose to describe the individual results and not to pool the data. If data were given in a chart, we deduced the numbers from the chart.

Where possible, all data that we extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis in which all data were analysed in groups to which they were assigned. We stated if this was not possible. We noted the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported. We reported the 95% CIs for all analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

We included between‐participant data as well as within‐participant data. In general, within‐participant studies apply the intervention to a body part such as a limb and the comparator to a different body part such as the opposite limb (e.g. right arm versus left arm). Those data are distinct. Consequently, we separately analysed and reported information on between‐participant data and within‐participant data. PASI‐75 is the primary efficacy outcome for both data types.

If studies reported multiple intervention groups, we designated the intervention group and each different comparator group.

Dealing with missing data

We conformed to Cochrane's principal options for dealing with missing data (Higgins 2011). If data were missing, or only imputed data were reported, we planned to contact trial authors to request data on the outcomes of the people or limbs of the study. When relevant data regarding study selection, data extraction, and 'Risk of bias' assessment were missing, we planned to contact study authors to retrieve the missing data. If data remained missing after contact with authors, we analysed only the available data and addressed the potential impact on the findings in the Discussion.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess heterogeneity (composed of dissimilar parts) between studies by visual inspection of forest plots; by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials that could not be ascribed to sampling variation (I² statistic) (Higgins 2003); and if possible, by subgroup analyses. If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we planned to investigate and report the possible reasons for this. An I² statistic greater than 50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity, demonstrating a considerable variation in results. In this case, we planned to present the graphical display of a forest plot, but we did not plan to report an average value for the intervention effect.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess study protocols to see if the planned outcomes have been reported, but did not identify any. We planned to assess reporting bias, such as publication bias, by constructing a funnel plot if there were a sufficient number of included studies for a particular outcome (that is, at least 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis).

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using the Review Manager 5.3 software (Review Manager 2014); one review author entered the data (FP) and another review author checked it (SP). If sufficient clinically similar studies were available, we deemed it feasible to pool data. We planned to consider clinical homogeneity and statistical heterogeneity before pooling the data. If the I² statistic value was greater than 50%, we did not combine studies in order to report an average value for the intervention effect. We planned to use random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting for all analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

Concerning the dichotomous events of PASI‐75 and treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal, we pooled the data and estimated a risk ratio and a P value for overall effect by using the Mantel‐Haenszel statistic and a fixed‐effect model.

Where possible, all data that we extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis in which all data were analysed in groups to which they were assigned. We stated if this was possible. We noted the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported. We reported the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all analyses.

We planned to use ordinal data from people who answered the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire (Table 3) (Melilli 2006) or the visual analogue scale (VAS) on pruritus (itching), as well as from people who achieved a remission and people who experienced secondary malignancy. However, these data were not reported.

In the protocol, we addressed a problem that might arise if we included only a single study in an analysis of dichotomous data. In this instance, the confidence intervals around risk ratios calculated in Review Manager 2014 are unreliable. Where results were estimated for individual studies with low numbers of outcomes (less than 10 in total), or where the total sample size was less than 30 people, or limbs and a risk ratio was used, we planned to report the proportion of outcomes in each treatment group together with a P value from a Fisher's exact test. But this problem did not arise.

The analysis should be in intention‐to‐treat and all missing data were considered as failure.

Results on outcomes that were not predefined were also reported in Effects of interventions as additional information, though, the results were not relevant for the conclusion of the present review.

'Summary of findings' tables and GRADE assessments

We prepared one 'Summary of findings' table using the GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro GDT 2014) concerning the comparison of between‐participant data: salt bath + UVB compared with other treatment + UVB. We listed the predefined two primary outcomes: PASI‐75 and treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal. For each outcome, two review authors (FP, SP) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence by using the five GRADE considerations, that is, study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). Due to lack of data, we did not prepare other 'Summary of findings' tables, which might be possible for comparison type one regarding between‐participant data and for both comparison types regarding within‐participant data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not undertake any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis removing studies at high or uncertain risk of bias. However, we did not undertake any sensitivity analyses due to the limited number of studies included in this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The Electronic searches of databases and online trials registers retrieved 281 records (142 from databases and 139 from online trials registries) once duplicates were removed (Figure 1). We screened the title and abstract of 281 records and excluded 254 records. We screened the full texts of the remaining 27 records and included 11 records and did not include 16 records. The exclusion reasons for 15 records (Excluded studies) are shown in the Characteristics of excluded studies. One record is listed in Studies awaiting classification, and described in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. The latter record (NCT02713711) could be an eligible study for inclusion in a future update. The results and full description of the methods of the study were not available. We included eight studies (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007) associated with 11 records. For a full description of our screening process, see Figure 1.

Included studies

Of the 27 potentially relevant records, we included 11 records (Included studies), which are associated with eight different studies (Figure 1). The characteristics of the eight included studies are described in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Design and sample sizes

We included eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (2105 participants; 1976 analysed) in this review. Six studies were parallel RCTs (2035 participants; 1908 analysed) that randomised patients to an intervention or comparator group (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). Leaute‐Labreze 2001 randomised participants to an intervention group (24 analysed), or two different comparator groups (22 and 21 analysed). Schiener 2007 randomised participants to an intervention group (299 analysed), or three different comparator groups (270, 285, and 305 analysed). Two studies (70 participants; 68 analysed) were within‐participants studies (140 limbs; 136 analysed) (Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001). Dawe 2005 randomised arms or legs to an intervention or comparator group (120 limbs; 116 analysed), and Gambichler 2001 randomised elbows to an intervention or comparator group (20 limbs; 20 analysed). The majority of studies did not report the recruitment periods. The earliest reported recruitment happened in the year 2001.

Assessment at the end of treatment was reported by seven studies: up to eight weeks (Arnold 2001), six weeks (Brockow 2007a), six weeks (Brockow 2007b), eight weeks (Gambichler 2001), seven weeks (Klein 2011), three weeks (Leaute‐Labreze 2001), and eight weeks (Schiener 2007) after start of treatment. In one study (Dawe 2005), we did not identify a clear reporting of treatment duration. Assessment at the end of follow‐up was reported by six studies: up to eight months (Arnold 2001), six months (Brockow 2007a), six months (Brockow 2007b), 12 months (Dawe 2005), six months (Klein 2011), 12 months (Leaute‐Labreze 2001) after end of treatment. In two studies (Gambichler 2001; Schiener 2007), we did not identify a clear reporting of follow‐up duration. The duration of trials in total (start of treatment to end of follow‐up) was roughly: up to four months (Arnold 2001), up to eight months (Brockow 2007a), up to eight months (Brockow 2007b), at least 12 months (Dawe 2005), at least two months (Gambichler 2001), up to eight months (Klein 2011), up to 13 months (Leaute‐Labreze 2001), and at least two months (Schiener 2007).

Setting

Five of the eight included studies were set in Germany (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Schiener 2007), and a single study was set in the Netherlands (Arnold 2001), the UK (Dawe 2005), and France (Leaute‐Labreze 2001), respectively. Four studies were conducted in a single centre (Arnold 2001; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001; Leaute‐Labreze 2001), and the remaining four studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Schiener 2007) were conducted in more than one centre. Five studies reported the recruitment of outpatients (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Gambichler 2001; Schiener 2007), and the other three studies did not report any information on recruitment (Dawe 2005; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001). One single‐centre study was conducted in the Psoriasis Day Care Centre at Ede, the Netherlands. Another single‐centre study was conducted in a spa centre at Salies‐de‐Bearn, France. Two other single‐centre studies were conducted; one in Germany and one in the UK. Four multi‐centre studies were conducted in spa centres or outpatient clinics in Germany. Three of eight studies were sponsored by commercial spa or salt companies (German Spas Association (Deutscher Heilbäderverband); Mavena Healthcare AG, Switzerland, the commercial spa facility La Compagnie Fermiere de Salies de Bearn), one by health insurance companies ("primary" health insurance companies in Bavaria, Germany), one by an association of dermatologists (Berufsverband der Deutschen Dermatologen, Germany), and three did not report on funding.

Participants

The study participants were diagnosed with psoriasis by a dermatologist. Six studies reported a mean age range from 41 to 49 years of age in the intervention group, and from 45 to 50 years of age in the control group (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). One study reported a mean age of 36 years in the intervention group and 46 years of age in the comparator group (Gambichler 2001). One study did not report information on age (Dawe 2005). Four studies reported male gender from 56% to 74% in the intervention group and from 60% to 62% in the control group (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Schiener 2007). Two studies reported male gender in 40% and 57% for all people or limbs, respectively (Arnold 2001; Gambichler 2001). Two studies did not report information on gender (Dawe 2005; Leaute‐Labreze 2001).

All eight included studies reported on assessing the skin type by using the Fitzpatrick phototyping scale (Fitzpatrick 1988), which results in six categories. Most participants were categorised type III, in some studies, a considerable fraction of participants were also categorised II and IV. According to the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA): "The Fitzpatrick skin phototype is a commonly used system to describe a person's skin type in terms of response to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure." The various types correspond to pale white skin (I), white skin (II), light brown skin (III), moderate brown skin (IV), dark brown skin (V), and deeply pigmented dark brown to black skin (VI).

As a measure of severity of disease, the PASI score ranging from 0 to 72 points was assessed at the beginning of the study in five studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). In the test arm versus control arms, the median PASI score was 17 versus 16 (Brockow 2007a), 17 versus 18 (Brockow 2007b), 15.1 versus 15.3 (Klein 2011), 15.0 versus 15.7 (Leaute‐Labreze 2001), and 16 versus 16 versus 17 versus 17 (Schiener 2007). Concerning baseline PASI score, there was no imbalance between treatment arms. Three studies (Arnold 2001; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001) did not report the PASI score.

Four of the studies reporting between‐participant data (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Schiener 2007) stated the proportion of participants who had any experience of former phototherapy, which was balanced across the treatment groups. Three studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Schiener 2007) reported that between 80% and 90% of included participants had previous phototherapy, while one study (Klein 2011) reported a smaller proportion between 10% and 15%. One of the studies reporting within‐participant data (Dawe 2005) reported a proportion of 75%.

Four of the studies reporting between‐participant data (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Schiener 2007) stated the proportion of participants who had previous systematic therapy due to psoriasis, which was balanced across the treatment groups. Three studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Schiener 2007) reported that between 20% and 40% of included participants had previous systematic therapy, while one study (Klein 2011) reported a smaller proportion between 1% and 3%. One of the studies reporting within‐participant data (Dawe 2005) reported a proportion of 12%.

Three of the studies reporting between‐participant data (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Schiener 2007) stated the proportion of participants who had previous inpatient care due to psoriasis, which was balanced across the treatment groups. These studies reported that between 40% and 60% of included participants had previous inpatient care. Klein 2011 reported that about 55% of participants had previous topical treatment due to psoriasis.

Three studies reported on the duration of disease. Two of the studies reporting between‐participant data (Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007) reported a mean or median duration of 15 to 20 years. One of the studies reporting within‐participant data (Gambichler 2001) reported a mean duration of 2.5 years.

Interventions and comparisons

To make various salt concentrations comparable, we converted the information on salt solutions into the unit g/L (Table 4).

3. Salt concentrations.

| Study | Intervention | Comparator |

| Arnold 2001 | 6.7 g/L NaCl dissolved in tap water | 5.7 mg/L psoralen dissolved in tap water |

| Brockow 2007a | 250 to 270 g/L NaCl present in natural spring water | no bath |

| Brockow 2007b | 45 to 120 g/L NaCl present in natural spring water | no bath |

| Dawe 2005 | 150 g/L Dead Sea salt dissolved in tap water | no bath |

| Gambichler 2001 | 240 g/L NaCl dissolved in tap water | 0.2 g/L present in tap water |

| Klein 2011 | 100 g/L Dead Sea salt dissolved in tap water | no bath |

| Leaute‐Labreze 2001 | 250 g/L NaCl present in natural sping water | no bath |

| Schiener 2007 | 250 g/L NaCL dissolved in tap water | 0.5 mg/L psoralen dissolved in tap water |

NaCl: sodium chloride

Comparison 1: salt bath + UVB versus other treatment without UVB

We identified one comparison in one of the studies reporting between‐participant data (Schiener 2007). Schiener 2007 randomised 310 participants to the intervention group salt water + UVB and randomised 321 participants to the comparator group psoralen bath + UVA.

Schiener 2007: salt bath + UVB versus psoralen bath + UVA

We did not identify comparisons in the studies reporting within‐participants data

Comparison 2: salt bath + UVB versus other treatment + UVB or UVB only

We identified seven comparisons in the six studies reporting between‐participant data (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). UVB was applied in addition to another treatment, such as psoralen bath or tap water bath in two comparator groups. UVB only was applied in five comparator groups. Arnold 2001 randomised 20 participants to the intervention group salt water + UVB and 20 participants to the comparator group psoralen bath + UVB. Schiener 2007 randomised 310 participants to the intervention group salt bath + UVB, randomised 301 participants to the comparator group UVB only, and randomised 301 participants to tap water + UVB. The other studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001) randomised participants to the intervention group salt bath + UVB, and to the comparator group UVB only.

Arnold 2001: salt bath + UVB versus psoralen bath + UVB

Brockow 2007a: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Brockow 2007b: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Klein 2011: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Leaute‐Labreze 2001: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Schiener 2007: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Schiener 2007: salt bath + UVB versus tap water + UVB

We identified two comparisons in the two studies reporting within‐participants data (Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001). Both studies randomised body parts to salt water + UVB versus UVB only.

Dawe 2005: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Gambichler 2001: salt bath + UVB versus UVB only

Salt bath

People, legs, arms, or elbows were soaked for 15 to 30 minutes in salt water with a sodium chloride salt concentration ranging from 0.8 g/L to 250 g/L. The sources were natural springs in three studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Leaute‐Labreze 2001), dissolved sodium chloride in tap water in three studies (Arnold 2001; Gambichler 2001; Schiener 2007), and dissolved commercial Dead Sea salt in tap water in two studies (Dawe 2005; Klein 2011). In general, salt bath + UVB was applied once a day, three to five days a week, for up to eight weeks, and reaching a maximum number of 15 to 35 applications.

UVB

For irradiation with UVB light, the studies used devices such as Philips (Eindhoven, the Netherlands) 100 Watts TL‐01 lamps. Four studies used only 311 nm narrowband UVB (Arnold 2001; Dawe 2005; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001), two studies used only 280 nm to 320 nm broadband UVB (Brockow 2007b; Gambichler 2001), and two studies used both (Brockow 2007a; Schiener 2007). Schiener 2007 reported a 300 nm to 320 nm 'selective phototherapy', which represents a part of the broadband UVB and which has been predominantly in German phototherapy centres. Some studies assessed a so‐called minimal erythema dose (MED) before treatment to determine a starting dose, which might be set at 50% of the MED. The MED was defined as the dose to produce a just‐detectable erythema with sharp borders within 24 hours in some uninvolved and untanned skin areas of 2 cm2. The authors of four studies reported mean starting doses from 0.02 J/cm2 to 0.4 J/cm2 (Brockow 2007b; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001). In general, UVB was applied once a day, three to five days a week, for up to eight weeks, and reaching a maximum number of 15 to 35 applications.

Cumulative UVB doses

Regarding the intervention (salt water bath + UVB), the authors of five studies (Brockow 2007a; Dawe 2005; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007) reported mean cumulative doses for primarily or only using narrowband UVB from 11.8 J/cm2 to 50.7 J/cm2 and the authors of two studies (Brockow 2007b; Gambichler 2001) reported mean cumulative doses for only using broadband UVB from 2.7 J/cm2 to 7.2 J/cm2. Regarding the comparator (UVB alone), the authors of seven studies reported mean cumulative doses for narrowband UVB from 12.5 J/cm2 to 41.3 J/cm2and for broadband UVB from 2.8 J/cm2 to 7.2 J/cm2 (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). One study did not report UVB doses (Arnold 2001).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Psoriasis area and severity index (PASI)‐75

Between‐participant data

Two of six studies (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b) reported PASI‐75.

Four of six studies (Arnold 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007) reported aggregate data on PASI, such as mean PASI and PASI‐50, but did not report PASI‐75 as defined in the inclusion criteria. It is not possible to deduce PASI‐75 from mean PASI or PASI‐50, but it is possible to calculate PASI‐75 if individual data are available. Therefore, we sent e‐mail requests to the authors of the respective studies to send us individual data on PASI. We used the e‐mail addresses provided by recent papers of the authors. If an e‐mail address was no longer active, we sent the request to an e‐mail address provided by the institution that was involved in the study. We sent enquiries to authors of all included studies. Detailed information is provided in Appendix 6. We asked for individual patient data on PASI of the studies by Arnold 2001, Brockow 2007a, Brockow 2007b, Klein 2011, Leaute‐Labreze 2001, and Schiener 2007 to enable a calculation of PASI‐75. We did not receive the requested information.

Within‐participant data

Two of two studies (Dawe 2005, Gambichler 2001) reported individual severity scores which are different from PASI, and they consequently did not report PASI‐75. We sent enquiries to authors of all included studies. Detailed information is provided in Appendix 6. We asked for individual patient data on PASI of the studies by Dawe 2005 and Gambichler 2001 to enable a calculation of PASI‐75. We did not receive the requested information.

Treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal

Between‐participant data

Two of six studies reported treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal (Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001). Four of six studies did not report this outcome.

Within‐participant data

One study (Dawe 2005) reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

The included studies did not report outcomes that were predefined as secondary by the present review including Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Pruritus severity using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 ('no itching') to 100 ('severe itching'), Time to relapse, and Secondary malignancies.

Excluded studies

Of 25 potentially relevant records, we excluded 15 records (Figure 1). One record (Studies awaiting classification) is awaiting classification and is described in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. The reason for exclusion of 15 records (Excluded studies) are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and are based on:

not intervention of interest (n = 6): Dead Sea bathing and sun exposure; geothermal sea bathing + UVB; sulphurous thermal spring water, bath not followed by UVB consistently; lagoon bathing followed by UVB; oral retinoid added to bath and UVB; and UVB but not salt water baths;

not study type of interest (n = 9): systematic review (n = 5); single‐arm study (n = 2); nonsystematic review (n = 2).

Studies awaiting classification

NCT02713711 randomised 24 adult participants with psoriasis in a single‐centre study in Chile. The number of participants correspond to the two treatment groups of interest. The intervention was salt bath followed by artificial UVB. The comparator was artificial UVB only. The study was sponsored by Universidad Catolica del Maule, Chile. This study is completed and the authors have submitted the manuscript. At the present time, the manuscript has not been accepted for publication. Thus, the results of the outcomes are not available yet (correspondence with study author shown in Appendix 6).

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias table in Characteristics of included studies provides details of each item of the risk of bias tool for randomised controlled trials. Figure 2 and Figure 3 provide an overview.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The authors of six studies clearly described an adequate random sequence generation and an adequate concealment of the allocation, which was judged as low risk of bias (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). In the other two studies, selection bias from random sequence generation and an adequate concealment of the allocation was judged as unclear risk of bias (Arnold 2001; Gambichler 2001).

Blinding

The authors of five studies reported that they did not blind investigators and patients and we judged a high risk of performance bias (Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). A further study did not report this topic so we also judged it as high risk of performance bias (Arnold 2001). One study reported the issue of blinding, but patients and nurses were not blinded (Dawe 2005). As physicians may have been blinded, we judged an unclear risk of performance bias. One other study reported partial blinding of people or limbs, and we judged an unclear risk of bias (Gambichler 2001).

Most of the studies tried to blind the persons involved in outcome assessment, but this could not be achieved in all cases. We judged a low risk of detection bias in four studies as the assessors were presumably unaware of patients' treatment assignments (Brockow 2007a; Gambichler 2001; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). We judged an unclear risk in two studies as the blinding was tried but was not achieved (Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005). The authors of one study did not report this topic so we considered it high risk of detection bias (Arnold 2001) . In addition, one study was considered at high risk as blinding was not implemented (Klein 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Concerning three studies, we were unsure whether a rather low proportion of dropouts or a high proportion of dropouts but the application of an intention‐to‐treat analysis may have affected the outcome (Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007). Therefore, we judged them at unclear risk of attrition bias. We judged attrition bias as high risk in three studies (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005) as a considerable number of patient data could not be used in the analysis. In two studies, we did not identify attrition bias and they were judged low risk of bias (Brockow 2007a; Gambichler 2001).

Selective reporting

No protocol was available for any included study. Thus, we searched for inconsistencies within the reporting of the article. We did not identify a selective reporting issue and judged all eight studies at unclear risk of reporting bias (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007).

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify a substantial source of other bias from the information available in the reports; hence, we judged all eight included studies at unclear risk of other sources of bias due to insufficient information available to make a full assessment (Arnold 2001; Brockow 2007a; Brockow 2007b; Dawe 2005; Gambichler 2001; Klein 2011; Leaute‐Labreze 2001; Schiener 2007).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: Salt bath plus UVB versus other treatment without UVB

Primary outcomes

PASI‐75 response

We did not identify appropriate data.

Treatment‐related adverse events requiring withdrawal

We did not identify appropriate data.

Secondary outcomes

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

We did not identify appropriate data.

Pruritus severity using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 ('no itching') to 100 ('severe itching')

We did not identify appropriate data.

Time to relapse

We did not identify appropriate data.

Secondary malignancies

We did not identify appropriate data.

Not predefined outcomes

We identified outcomes reported in the eight included studies that were not predefined by the current review. These outcomes should not have an impact on the conclusion. Nevertheless, the respective results should be reported to provide a broader picture of the results reported in the various studies.

PASI‐50 response (between‐participant data)