Nuclear import of viral genomes is an essential step to initiate productive infection for several nuclear replicating DNA viruses. On the other hand, DNA is not a physiological nuclear import substrate; consequently, viruses have to exploit existing physiological transport routes. Here, we show that adenoviruses use the nucleoporin Nup358 to increase the efficiency of adenoviral genome import. In its absence, genome import efficiency is reduced and the transport receptor transportin 1 becomes rate limiting. We show that the N-terminal half of Nup358 is sufficient to drive genome import and identify a transportin 1 binding region. In our model, adenovirus genome import exploits an existing protein import pathway and Nup358 serves as an assembly platform for transport complexes.

KEYWORDS: adenoviruses, nuclear import/export, nuclear pore, nup358, transportin, viral genome

ABSTRACT

Nuclear import of viral genomes is an important step during the life cycle of adenoviruses (AdV), requiring soluble cellular factors as well as proteins of the nuclear pore complex (NPC). We addressed the role of the cytoplasmic nucleoporin Nup358 during adenoviral genome delivery by performing depletion/reconstitution experiments and time-resolved quantification of adenoviral genome import. Nup358-depleted cells displayed reduced efficiencies of nuclear import of adenoviral genomes, and the nuclear import receptor transportin 1 became rate limiting under these conditions. Furthermore, we identified a minimal N-terminal region of Nup358 that was sufficient to compensate for the import defect. Our data support a model where Nup358 functions as an assembly platform that promotes the formation of transport complexes, allowing AdV to exploit a physiological protein import pathway for accelerated transport of its DNA.

IMPORTANCE Nuclear import of viral genomes is an essential step to initiate productive infection for several nuclear replicating DNA viruses. On the other hand, DNA is not a physiological nuclear import substrate; consequently, viruses have to exploit existing physiological transport routes. Here, we show that adenoviruses use the nucleoporin Nup358 to increase the efficiency of adenoviral genome import. In its absence, genome import efficiency is reduced and the transport receptor transportin 1 becomes rate limiting. We show that the N-terminal half of Nup358 is sufficient to drive genome import and identify a transportin 1 binding region. In our model, adenovirus genome import exploits an existing protein import pathway and Nup358 serves as an assembly platform for transport complexes.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleocytoplasmic transport of macromolecules occurs through nuclear pore complexes (NPC) embedded in the nuclear envelope. NPCs are macromolecular assemblies of ∼30 different individual nucleoporins (Nups), which form a symmetric octameric pore with a central channel, connecting nucleus and cytoplasm (1). Small molecules may diffuse between the compartments, while larger proteins and protein-RNA complexes are translocated by active transport (2). Very large assemblies (e.g., some viral capsids) can be excluded from translocation (3). Active transport of cargoes uses importins (Imp) or exportins as transport receptors, collectively also called karyopherins, which typically engage with short peptide motifs, acting either as a nuclear localization signal (NLS) or as an nuclear export signal (NES). Directionality of transport is controlled by karyopherin binding to RanGTP. Import complexes are assembled in the cytoplasm, where RanGTP concentrations are low, and dissociate in the nucleus upon binding of RanGTP to the importin. Exportins, on the other hand, need high concentrations of RanGTP inside the nucleus to bind NES-containing cargoes. Translocation through the NPC is facilitated by the interaction of transport complexes with Nups containing intrinsically disordered sequences enriched in phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats (see references 2 and 4 for reviews). Some FG-containing Nups, such as Nup214 and Nup358, are asymmetrically distributed at the periphery of the NPC, with both localizing at the cytoplasmic side of the NPC, where they serve as assembly or disassembly sites for transport complexes (5–7). Nup358 can also function as an E3 ligase for the small ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO (8). Furthermore, it interacts with the kinesin 1 heavy chain (9).

Unlike proteins and RNA, DNA is not a physiological substrate for nuclear transport. Consequently, DNA viruses infecting nondividing cells such as adenoviruses (AdV) must access and divert existing nuclear transport pathways to deliver their DNA genomes into the nucleus. AdV protect their ∼36-kbp double-stranded linear DNA genome from immune detection during cytoplasmic trafficking inside an icosahedral capsid that is about 90 nm in diameter (10). The viral DNA is covalently bound at each end by the terminal protein and organized into chromatin-like structures through binding to >500 copies of histone-like protein VII (pVII) (11). Additional viral proteins Mu, IVa2, and V contribute to genome packaging and condensation and form part of the viral core inside the capsid. AdV enter the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Following uptake, the internal membrane lytic capsid protein VI (pVI) is released and allows endosomal escape in an autophagy-assisted process. Cytoplasmic particles are transported along microtubules toward the nucleus (12–15). Unloading from the microtubules to the NPC is triggered by an unknown mechanism involving the exportin CRM1 (16–18). At the NPC, particles bind to Nup214 (19, 20). Because the capsid exceeds the size limit for nuclear import, further disassembly steps liberate the genome for translocation to the nucleus. Viral core protein VII contains several functional NLSs that mediate binding to different importins. It remains bound to viral DNA during import. Thus, it has been proposed to drive genome import following genome release from the capsid at the NPC (21, 22). It has been suggested that AdV capsid disassembly at the NPC involves nucleoporin Nup358 and capsid protein IX (23). On the other hand, partial knockdown of Nup358 had no effect on AdV infection (20). Additional factors may contribute to capsid disassembly, including histone H1, which was reported to recognize a specific hypervariable loop present in the capsid protein hexon of HAd5-C2 (19) and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mib1 (24). The impact of different transport receptors on AdV genome delivery remains unclear. Inhibiting CRM1 with leptomycin B (LMB) entraps the AdV capsids at the microtubule organizing center (MTOC), precluding viral capsid docking and disassembly at the NPC and thus indirectly affecting AdV genome import (16, 18). A more direct role in genome import was suggested for transportin 1 (TRN1) and possibly additional transport receptors by interactions with genome bound protein VII (21, 22).

In this report, we address the role of Nup358 during AdV genome delivery using small interfering RNA (siRNA)/short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated depletion of the nucleoporin. We found that Nup358-depleted cells display reduced efficiencies of nuclear import of AdV genomes. We observed that transportin 1 is rate limiting for AdV genome import in Nup358-depleted cells. We show that the presence of the N-terminal half of Nup358 is sufficient to compensate for the import defect independently of protein IX (pIX). Taking the data together, Nup358 may promote the assembly of karyopherins on the viral genome, permitting AdV to exploit a physiological protein transport pathway for accelerated nuclear import of its DNA.

RESULTS

Nup358 depletion delays adenoviral genome import.

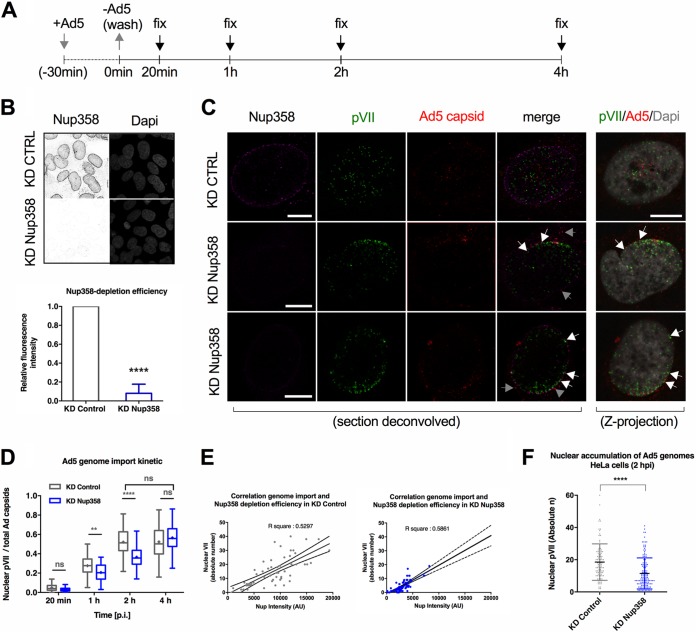

To address whether Nup358 plays a specific role in adenoviral genome import, we first depleted U2OS cells using siRNAs against Nup358 or nonspecific siRNAs as a control. At 72 h after siRNA transfection, cells were infected with Ad5-wt-GFP (wild type-green fluorescent protein) vector particles (Ad5) and genomes and viral capsids were quantified at 20 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 1A). Note that during the time frame analyzed in this study (up to 4 hpi), no detectable GFP is expressed from the vectors used. Importantly, Nup358 depletion levels were analyzed at the individual cell level by immunofluorescence (IF) staining. Only cells with a ≥90% reduction of the Nup358 fluorescence signal were considered efficiently depleted (Fig. 1B). First, we analyzed Ad5 genome delivery through quantitative immunofluorescence analysis using specific antibodies against the adenoviral capsid and against protein VII as a marker for viral genomes (Fig. 1C). Incoming intact viral capsids not exposing the viral genome were negative for protein VII (Fig. 1C). Colocalization between Ad5 capsid and protein VII signals was exclusively observed at the nuclear periphery consistent with the disassembly of the viral capsid and exposure of the viral genome taking place at the NPC (Fig. 1C), as previously shown (25). Protein VII signals negative for Ad5 capsid colocalizing with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) stain in z-projections were considered representative of released and imported genomes (Fig. 1C) (20, 24–26). We next determined the ratio of nuclear pVII dots and the total number of Ad5 capsid signals over time to estimate genome import efficiency in control cells and in Nup358-depleted cells (Fig. 1D). We observed a progressive increase in the levels of imported Ad5 genomes in control cells, which reached a plateau at 2 hpi. In Nup358-depleted cells, the number of imported genomes was reduced in a statistically significant manner compared to control cells at 2 hpi. This moderate reduction in import was also seen when shRNAs instead of siRNAs were used for the depletion of Nup358 (see below). At 4 hpi, similar levels of genome import were observed under both conditions. To corroborate our findings, we investigated the dependency of genome import rates on Nup358 levels in control cells in addition to depleted cells. We plotted the number of pVII dots after 2 hpi against the fluorescence intensities of Nup358 (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, control cells exhibited a range of endogenous Nup358 levels which strongly correlated with genome import efficiencies, a correlation that was also observed in Nup358-depleted cells (Fig. 1E). To exclude cell-type-specific effects, we next infected control and Nup358-depleted HeLa cells and analyzed nuclear import of Ad5 genomes (Fig. 1F). Similarly to our observations in U2OS cells, nuclear import of viral genomes was reduced at 2 hpi in cells that had been treated with siRNAs against Nup358 (Fig. 1F). Together, these results suggest that genome delivery is less efficient but not completely inhibited upon Nup358 depletion.

FIG 1.

Nup358 depletion delays adenoviral genome import. (A) Schematic representation of experimental design. U2OS cells were infected for 30 min, and unbound viruses were washed off at time point zero [t(0)]. Arrows point at the times of cell fixation after inoculum removal. (B) (Top panel) Control (knockdown) (KD CTRL) cells or Nup358-depleted (KD Nup358) cells were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies against Nup358 and DAPI to stain nuclei. (Bottom panel) The graph shows the mean (±SD) fluorescence intensity of endogenous Nup358 in depleted cells (KD Nup358) relative to control cells (KD Control). Results are from three independent experiments performed with n = >60 cells per condition; two-tailed t-test. (C) Representative single deconvolved sections or Z-projection confocal images (indicated on the bottom) of control cells (KD CTRL) and Nup358-depleted cells (KD Nup358; two rows with identical conditions) at t = 2 hpi. Antibodies detecting Nup358 (magenta signal), pVII (green signal), Ad5 capsids (red signal), or DAPI (gray signal) are indicated on the top of each column. Arrows indicate capsids negative (gray) or positive (white) for protein VII. Bars, 10 μm. (D and E) Quantification of the experiment whose results are depicted in panel C. (D) The graph shows quantification of imported genomes at the indicated time points in control (gray) versus KD Nup358 (blue) cells, normalized by the total number of cell-associated capsids and depicted as box-and-whiskers plots (n > 30 cells per condition/time point). (E) Correlation of Nup358 expression levels (x axis) versus number of nuclear protein VII dots (y axis) determined in control cells (gray, left panel) and KD Nup358 cells (blue, right panel). Linear regression and R squared data are indicated (n > 30 cells per condition/time point). (F) HeLa cells were infected for 30 min, and unbound viruses were washed off at time point t = 0. The graph shows quantification of imported genomes in HeLa cells at t = 2 hpi in control (gray) versus KD Nup358 (blue) cells as a box-and-whiskers plot of absolute numbers of nuclear genomes (n > 30 cells per condition/time point).

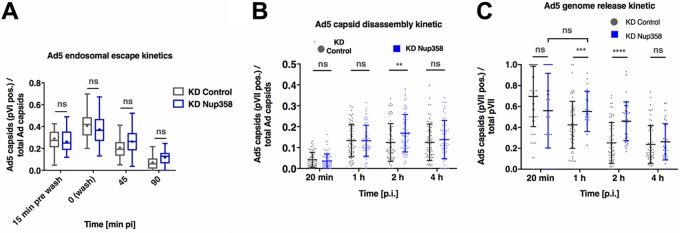

To confirm that depletion of Nup358 does affect genome delivery at the NPC and not upstream trafficking events, we monitored the exposure kinetic of internal capsid protein VI taking place during Ad5 endosomal escape (13). In both Nup358-depleted and control cells, levels of capsids positive for protein VI peaked about 30 min after virus addition (time point 0 min in Fig. 1A), followed by a decrease in the levels of protein VI-associated capsids over time (Fig. 2A). This reflects progressive endosomal escape of viral particles into the cytoplasm and shows that Ad5 entry steps prior to the arrival at the NPC are not affected by Nup358 depletion.

FIG 2.

Nup358 depletion specifically affects adenoviral genome import. (A) U2OS cells were subjected to Nup358 depletion and viral infection using Ad5-wt-GFP viruses. The graph shows quantification of the capsid endosomal escape kinetic at the indicated time points, calculated as the number of Ad5 capsids positive for pVI relative to the total number of Ad5 capsids per cell in control (gray) versus KD Nup358 (blue) cells. Infections were carried out for 30 min at 37°C followed by inoculum removal (t = 0). Time point −15 min corresponds to 15 min before inoculum removal (n > 30 cells per condition/time point)*. (B) An experiment was performed as described in the Fig. 1D legend. Data represent results of quantification of capsid disassembly kinetic, calculated as the number of pVII-positive Ad5 capsids, relative to the total number of Ad5 capsids per cell (n > 30 cells per condition/time point)*. (C) An experiment was performed as described in the Fig. 1D legend. Data represent results of quantification of genome release kinetics from Ad5 capsids, calculated as the number of pVII-positive Ad5 capsids relative to the total number of detectable pVII per cell (n > 30 cells per condition/time point)*. *, the results of the experiment were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple-comparison post hoc test.

To discriminate between a role for Nup358 in capsid disassembly at the NPC and a role in genome import, we next investigated if Nup358 depletion would affect capsid disassembly kinetics. Capsid disassembly was calculated as the ratio of capsids exposing genomes (pVII-positive capsids) to total detectable capsids (pVII-positive and pVII-negative capsids, i.e., intact capsids). The ratio of capsids exposing genomes in control cells increased from 20 min to 1 hpi, coinciding with their arrival at the NPC, and remained at a constant level from 1 to 4 hpi (Fig. 2B). Strikingly, Ad5 capsids initially disassembled as efficiently in Nup358-depleted cells as in control cells and with similar kinetics (time points 20 min postinfection and 1 hpi). However, the ratio of capsids exposing genomes in Nup358-depleted cells was elevated at 2 hpi, while this ratio dropped back to the level seen with the control cells at 4 hpi. These results suggest that capsid disassembly was not affected by Nup358 depletion and that the differences observed at 2 hpi were due to the accumulation of nonimported genomes resulting from inefficient genome import at unaltered disassembly rates.

We next quantified the kinetics of genome import in the presence and absence of Nup358 on the same data set (Fig. 1A to E). We operationally defined genome import as the separation of the genome from the capsid. The value representing genome import was calculated as the ratio of capsid-associated genomes (pVII-positive capsids) to total detectable genomes (pVII-positive capsids plus free pVII) over time. We observed that at 20 min postinfection, most genomes were still associated with capsids in Nup358-depleted and control-depleted cells (Fig. 2C). The proportion of capsid-associated genomes decreased over time in the control cells, with most viral genomes having separated from Ad5 capsids as early as 2 hpi. In Nup358-depleted cells, larger amounts of genomes remained associated with Ad5 capsids at 1 and 2 hpi in a statistically significant manner. At 4 hpi, most genomes were no longer associated with capsids under both conditions, corroborating our previous findings (Fig. 1D).

Taken together, these results show that depletion of Nup358 delays adenoviral genome delivery by affecting specifically the import step, rather than arrival or disassembly of adenoviral capsids at the NPC.

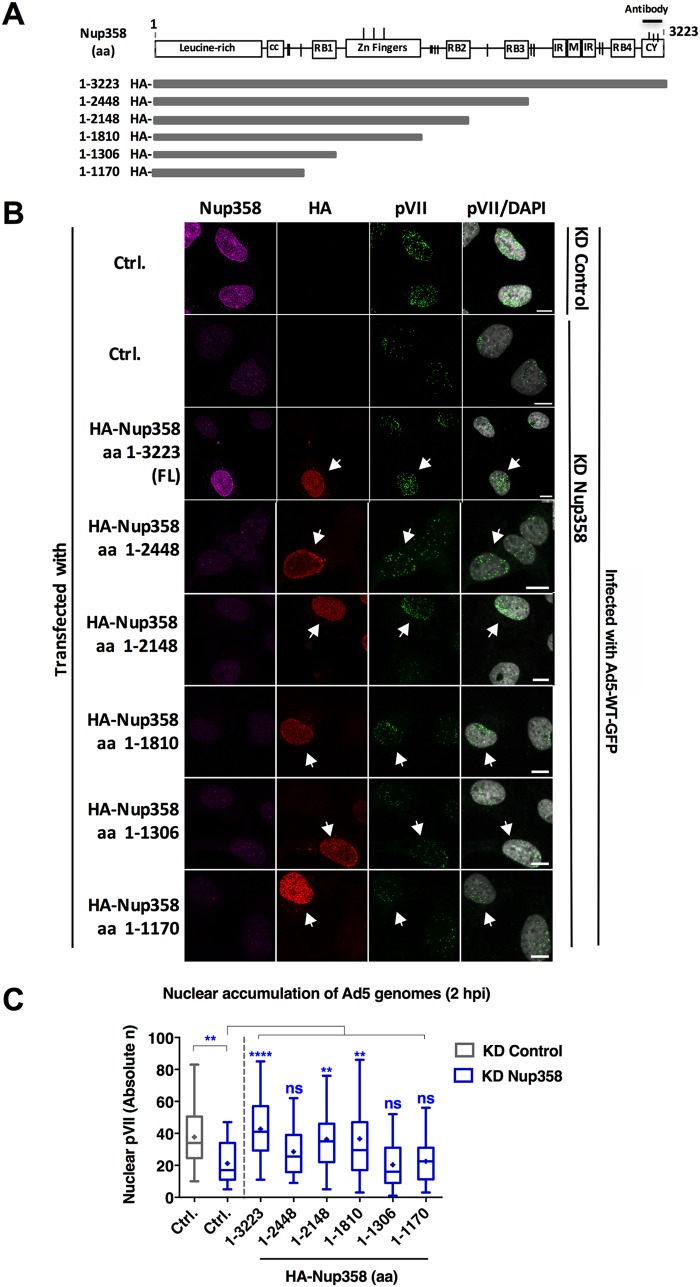

The N-terminal half of Nup358 is sufficient to promote efficient adenoviral genome import.

To confirm a specific role for Nup358 in adenoviral genome import and to exclude off-target effects in the siRNA experiment, as well as to identify the region of Nup358 facilitating adenoviral genome import, we adapted a combined depletion/reconstitution approach previously used to reconstitute nuclear transport of proteins (27). Several siRNA-resistant Nup358 constructs, all associated with the N-terminal NPC-anchoring domain, were expressed in Nup358-depleted U2OS cells (Fig. 3A). To confirm efficient depletion of endogenous Nup358 and discriminate endogenous Nup358 from exogenous Nup358, we used antibodies against the C-terminal cyclophilin-like domain of Nup358, which was absent from the truncated fragments (Fig. 3A). All constructs included an N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, allowing specific analysis of Nup358-depleted cells which were negative for the specific Nup358 antibody. For cells expressing full-length HA-Nup358, we analyzed only the cells in the vicinity of efficiently Nup358-depleted cells (Fig. 3B, third row). Following depletion-reconstitution, we quantified the import kinetics of adenoviral genomes upon infection. Transfected cells were infected with Ad5-wt-GFP and analyzed at 2 hpi, when the differences in the import efficiencies of the control and Nup358-depleted cells were most prominent (compare Fig. 1D). The absolute number of pVII dots in the nucleus (DAPI positive) of Nup358-depleted cells was significantly decreased compared to the number seen with the control-depleted cells, confirming that nuclear accumulation of viral genomes was less efficient in the absence of Nup358 (Fig. 3C). Strikingly, depleted cells expressing full-length reconstituted HA-Nup358 (amino acids 1 to 3223) accumulated Ad5 genomes as efficiently as nondepleted control cells. Statistically significant restoration of import was also achieved with shorter N-terminal Nup358 fragments (i.e., amino acids 1 to 2448, 1 to 2148, and 1 to 1810) (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, fragments containing only the first 1,170 or 1,306 amino acids (aa) of Nup358 did not restore Ad5 genome import (Fig. 3B and C). These results show that Nup358 facilitates adenoviral genome import and identify the N-terminal half of Nup358 as a region that promotes adenoviral genome import. Importantly, the C-terminal part of Nup358, containing 3 of 4 Ran-binding domains (RanBDs), a region involved in SUMO binding, and the kinesin-1 binding domain, was not required to restore import.

FIG 3.

The N-terminal half of Nup358 is sufficient to promote efficient adenoviral genome import. (A) Schematic representation of the siRNA-resistant, HA-tagged constructs of Nup358 used in this assay (27). Numbers to the left of the horizontal bars representing the fragments indicate the corresponding amino acids (aa) present in each fragment. Domains of Nup358 are represented as boxes (cc, coiled coil domain; RB1, RB2, RB3, and RB4, Ran-binding domains; IR, internal repeat region; M, middle region; CY, cyclophilin-like domain), and vertical dashes show the positions of FG repeats. The N-terminal HA-epitope tag and the C-terminal antibody epitope in the CY of Nup358 are indicated. (B) U2OS cells were transfected with HA-tagged Nup358 fragments as indicated to the left, infected with Ad5-wt-GFP, fixed at 2 hpi, and processed for IF. Representative maximum projection confocal images of pVII accumulation in the nucleus of control cells (KD Control) or Nup358-depleted cells (KD Nup358), either control transfected (Ctrl.) or expressing full-length (FL) Nup358 or Nup358 truncation mutants as indicated, are shown. Antibodies used to detect endogenous Nup358 (magenta), the HA-epitope tag of transfected Nup358 (red), pVII (green), or pVII merged with the DAPI signal to mark the nucleus are indicated above each column. Note that the Nup358 antibody recognized the FL construct but not the truncation mutants. Arrows indicate cells expressing HA-Nup358 constructs. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of Ad5 genome import in control cells (gray) or KD Nup358 cells (blue) at t = 2 hpi represented as a box plot (n > 30 cells per condition). Results were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. Significance is indicated with respect to levels in control-transfected KD control cells (gray box).

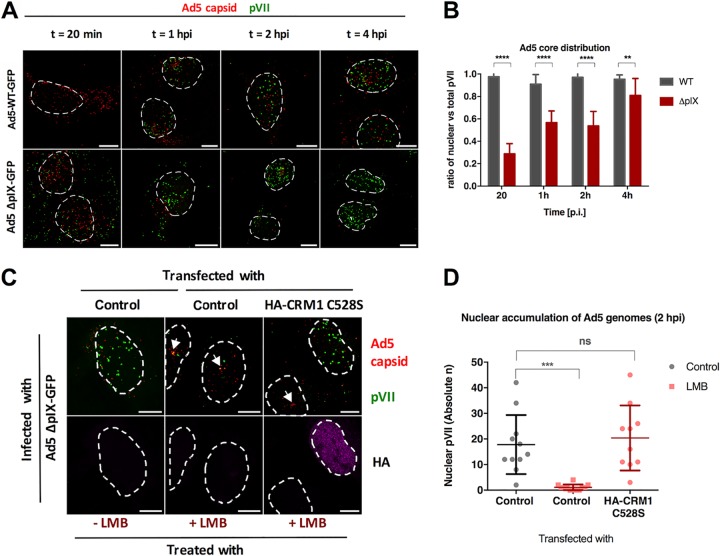

Capsid protein IX is dispensable for adenoviral genome import.

It was previously reported that Nup358 affects capsid disassembly at the NPC through indirect binding to minor capsid protein IX via kinesin-1 to prime the genome for nuclear import (23). Our results obtained so far do not support such a model because the presence of the N-terminal part of Nup358 lacking the kinesin-1-binding domain is sufficient to facilitate genome import. To further address this issue, we compared results of analyses of genome import of viruses containing (Ad5-wt-GFP) or lacking (Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP) the minor capsid protein IX (Fig. 4). Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP-infected cells showed several cytoplasmic viral genomes separated from the capsid (i.e., pVII signals) as early as 20 min postinfection (Fig. 4A; bottom row) (28–30). This was not observed in Ad5-wt-GFP-infected cells (Fig. 4A; top row). From 1 hpi to 4 hpi, cytoplasmic genomes disappeared and nuclear genomes appeared progressively for Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP. For Ad5-wt-GFP, no cytoplasmic genomes were detected and nuclear genomes started to appear also from 1 hpi as shown before (Fig. 4B). Two explanations for the observed accumulation of nuclear genomes originating from pIX-lacking capsids are possible. First, the cytoplasmic genomes that we observed after 20 min of infection might have been imported into the nucleus. Second, these cytoplasmic genomes might have been degraded and the nuclear pVII signals might have been derived from a pool of intact viral particles. To distinguish between these possibilities, we infected cells with Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP in the presence of the CRM1 inhibitor LMB, which induces accumulation of capsids at the MTOC, preventing them from docking and disassembling at the NPC (31). In the presence of LMB, at 2 hpi Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP capsids were retained at the MTOC and no nuclear pVII was detected (Fig. 4C). Some cytoplasmic genomes were still observed under these conditions, suggesting that (i) they were not imported and (ii) they did not originate from capsid disassembly at the NPC because the LMB prevented NPC docking. Overexpression of the LMB-resistant CRM1 C528S mutant reversed the LMB effect and restored genome import, showing that genome delivery is strictly dependent on the presence of functional CRM1 as reported previously for Ad5-wt-GFP particles (Fig. 4C and D) (31). These data suggested that some Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP capsids disintegrate prematurely in the cytoplasm, exposing genomes which are rapidly degraded and that do not contribute to the pool of imported viral genomes. Instead, a subpopulation of intact Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP particles succeeds in reaching the nuclear periphery and depends on CRM1 to deliver the viral genome. These capsids are affected by CRM1 inhibition via LMB, suggesting that they use the same NPC-dependent disassembly mechanism as do wt capsids even though they lack the pIX capsid protein. Taking the results together, neither protein IX nor Nup358 plays a dominant role in adenoviral capsid disassembly at the NPC and genome import.

FIG 4.

pIX is not required for capsid disassembly and adenoviral genome nuclear import. U2OS cells were subjected to viral infection using Ad5-wt-GFP or pIX-deleted mutant Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP, and the cells were fixed at the indicated time points. (A) Representative maximum projection confocal images of imported genomes comparing Ad5-wt-GFP (top row) and Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP (bottom row). Antibodies used to detect Ad5 capsid (red) or protein VII (green) are indicated. Dashed lines represent the edges of the nucleus. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of the proportion of nuclear pVII dots with respect to the total number of pVII dots per cell (n > 10 per condition) in the case of Ad5-wt-GFP (gray) or Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP (red) virus infection. Error bars represent SD. Results were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. (C) Representative maximum projection confocal images of the nuclear accumulation of viral genomes in Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP-infected cells at t = 2 hpi in the absence or presence of LMB (indicated on the bottom) transfected either with control plasmids or with plasmids expressing the LMB-resistant HA-CRM1 C528S mutant (indicated on the top). Antibodies used to detect capsids (red) and protein VII (green) or the HA tag of transfected CRM1 (magenta) are indicated to the right of each row. Dashed lines represent the edges of the nucleus defined using DAPI staining, and arrows point at capsid accumulation at the MTOC. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Quantification of the absolute number of nuclear pVII at t = 2 hpi with and without LMB treatment and CRM1 rescue as indicated. Scatterplots represent data obtained from at least 10 cells per condition and analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. Significance is indicated with respect to nontreated control transfected cells.

Transport receptors compensate for the lack of Nup358 in adenoviral genome import.

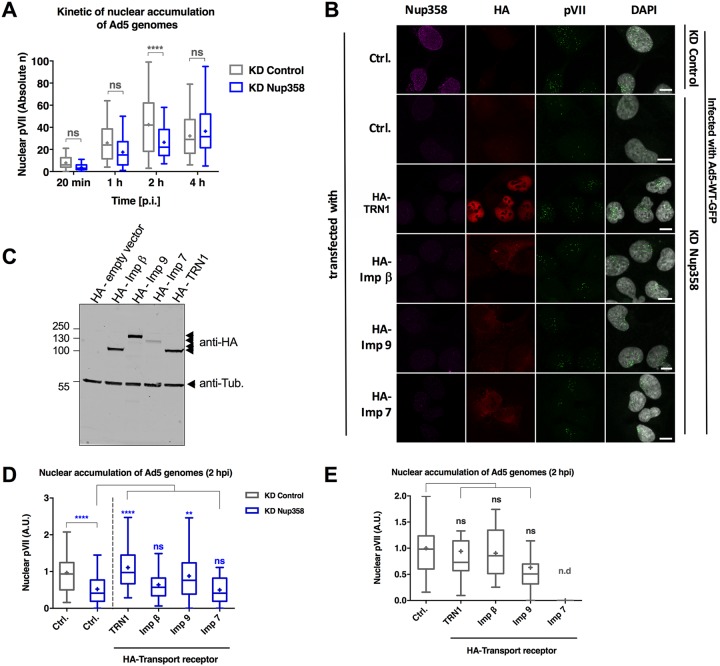

Our results showed that Nup358 depletion delayed but did not block adenoviral genome import. Nup358 could affect nuclear import at different levels. First, it could serve as a binding platform for import factors, facilitating the formation of karyopherin-containing transport complexes (6, 32). Hence, in the absence of Nup358, transport receptors may become rate limiting also for viral genome import. Second, Nup358 could interact directly with certain proteins, promoting their nuclear translocation (27). To discriminate between these possibilities, we set out to express HA-tagged importins in Nup358-depleted cells followed by infection with Ad5-wt-GFP. In this experiment, we used shRNA-mediated depletion of Nup358 using a validated protocol (20). Genome import at 2 hpi in shRNA Nup358-depleted cells was significantly reduced compared to control cell results (Fig. 5A), confirming our results described above using siRNAs for depletion (Fig. 1D). Next, we expressed HA-tagged transport factors such as transportin 1 (TRN1), importin β (Impβ), importin 9 (Imp9), and importin 7 (Imp7) in Nup358-depleted cells. Expression of the importins was examined by microscopy (Fig. 5B) and Western blotting (Fig. 5C). Strikingly, nuclear accumulation of Ad5 genomes at 2 hpi was restored to control levels in cells lacking Nup358 but expressing exogenous transportin 1 (Fig. 5D). To a lesser extent, exogenous importin 9 also promoted genome import in Nup358-depleted cells. Expression of exogenous importin β and importin 7, by contrast, hardly compensated for the lack of Nup358. Importantly, expression of exogenous transportin 1, importin β, or importin 9 in cells with endogenous Nup358 did not result in increased Ad5 genome import, suggesting that Nup358 regulates genome import through access to specific transport receptors (Fig. 5E).

FIG 5.

Transport receptors compensate for the lack of Nup358. (A) The graph shows quantification of imported genomes at indicated time points in control (gray) versus KD Nup358 (blue) cells as a box-and-whiskers plot using shRNA transfection as the depletion method in U2OS cells (n > 30 cells per condition/time point were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple-comparison post hoc test). (B) Representative maximum projection confocal images of pVII accumulation in the nucleus of control and Nup358-depleted U2OS cells and of cells infected with Ad5-wt-GFP (t = 2 hpi) cells and transfected with an empty control plasmid or expressing different HA-tagged import receptors (indicated to the left of each row). Antibodies used to detect endogenous Nup358 (magenta), the HA-epitope tag of transfected transport receptors (red), pVII (green), or pVII merged with the DAPI signal to mark the nucleus are indicated above each column. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Western blot of U2OS cells transfected with the individual HA-tagged transport receptor as indicated above each lane and probed with anti-HA antibodies (arrowheads to the right) and anti-tubulin (anti-Tub.) antibodies for a loading control. Note that the reduced Imp7 signal results from toxicity in overexpressing cells. (D) Quantification of data from the experiment whose results are presented in panel B. The graph shows nuclear accumulation of Ad5 genomes in control cells (gray) or KD Nup358 cells (blue) at t = 2 hpi. Individual cell values were normalized relative to the control in each experiment and are represented as arbitrary units (A.U.). Values were derived from results from two independent experiments performed with n = >25 cells per condition for each experiment*. Significance is indicated with respect to control transfected KD Nup358 cells. (E) Experiment performed in nondepleted control cells as described for panel D. Note that the importin 7 condition in the control cells could not be quantified due to low cell viability (n.d) (n > 25 cells per condition)*. *Results of experiments were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test.

Together, these results show that transport receptors are rate limiting for adenoviral genome import in the absence of Nup358. They suggest a role for Nup358 in maintaining a high local concentration of importins at the NPC to facilitate the formation of adenoviral-genome-associated import complexes, preferentially with transportin 1.

Ad5 genome import is not exclusively mediated by transportin 1.

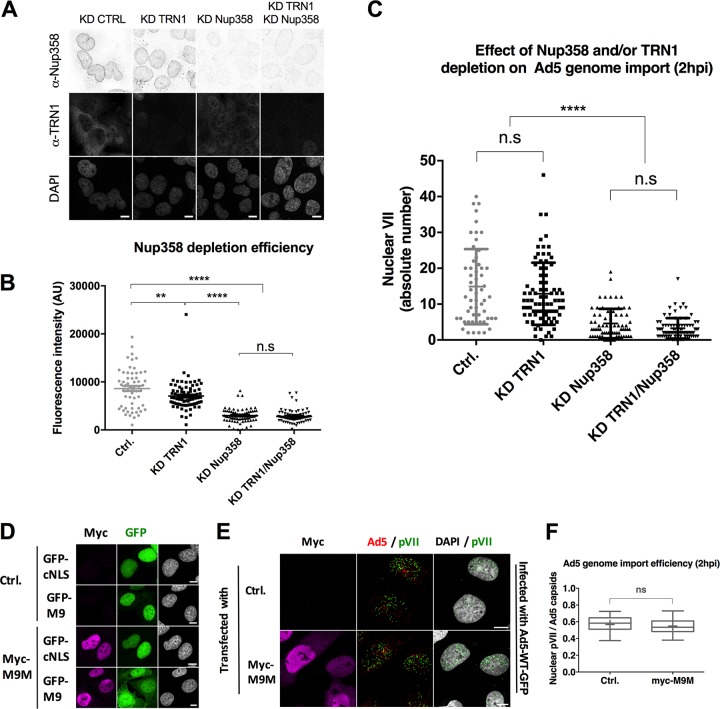

Our results described above showed that transportin 1 promotes adenoviral genome import. We next asked whether transportin 1 is the main import receptor for adenoviral genomes. To address this question, we used two different approaches: depletion of transportin 1 using specific siRNAs and pathway-specific inhibition using a competitive transport cargo. In the depletion approach, efficient knockdown of transportin 1 and/or Nup358 in U2OS cells was reached 72 h after siRNA transfection (Fig. 6A and B). Cells were then infected with Ad5-wt-GFP and analyzed 2 hpi. Only a slight reduction in Ad5 genome import was observed in transportin 1-depleted cells compared to control cells (Fig. 6C). In contrast, a significant decrease in genome import efficiency was clearly observed in both Nup358-depleted cells and cells lacking both Nup358 and transportin 1, compared with control cells (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

Specific depletion or inhibition of transportin 1 does not impact adenoviral genome import. (A to C) U2OS cells were treated with siRNAs to deplete transportin 1 (TRN1) and/or Nup358 or with control siRNAs (KD CTRL) as indicated and infected with Ad5-wt-GFP. (A) Overview of field of cells stained with anti-Nup358 antibody (top row) or anti-TRN1 antibody (middle row) or DAPI (bottom row). (B) Quantification of Nup358 depletion levels in control, KD TRN1, KD Nup358, or double-KD TRN1/Nup358 cells, indicated as total nuclear fluorescence. Scatterplots show data obtained from two independent experiments (n > 30 per condition) analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. Note that TRN1 depletion also partially reduced Nup358 fluorescence. (C) Quantification of Ad5 genome import efficiency in control (gray), KD TRN1 (turquoise), KD Nup358 (blue), or double-KD TRN1/Nup358 cells, indicated as the total number of nuclear pVII dots. Pooled data obtained from two independent experiments (n > 30 per condition) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with an empty plasmid (Ctrl.) or with plasmids coding for myc-tagged MBP-M9M (Myc-M9M) and in each case were either cotransfected with a reporter for importin α/β-mediated transport (GFP-cNLS) or transportin-mediated transport (GFP-M9) as indicated. Expression was detected with myc-tag-specific antibodies (M9M, magenta) or via the GFP signal (cNLS or M9, green), as indicated. (E) Representative maximum projection confocal images of control transfected cells (top row) or myc-MBP-M9M transfected U2OS cells (bottom row) infected with fluorescently labeled Ad5-wt-A594 (red) and fixed at t = 2 hpi. Antibodies used to detect the myc tag (magenta), pVII (green), or the DAPI signal are indicated on top of each row. Bars, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of data from the experiment whose results are presented in panel E showing Ad5 genome import efficiency in mock-treated or myc-M9M-expressing cells, calculated as the number of nuclear pVII dots normalized by data from cell-associated capsids. Box plot represents data (n > 30 per condition) analyzed using a two-tailed t-test.

Next, we transfected U2OS cells with a construct coding for a myc-tagged M9M peptide-encoding fusion protein, a high-affinity cargo that inhibits transportin 1-dependent import of other cargos (33). To control specific inhibition of the transportin 1 pathway, cells were transfected with a plasmid coding for GFP-M9, a reporter containing the NLS of hnRNP A1, which is specifically recognized by transportin 1. Alternatively, cells were transfected with a plasmid coding for GFP-cNLS as a reporter, which is imported by the importin α/β complex. All cells were cotransfected with the myc-tagged M9M inhibitor and subjected to IF analysis to assess GFP-tagged NLS constructs localization. Whereas expression of myc-M9M caused partial relocalization of GFP-M9 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, GFP-cNLS was not affected, confirming the specific inhibition of transportin 1-dependent import (Fig. 6D). However, myc-M9M did not cause any reduction in Ad5 genome import in U2OS cells infected with Ad5 compared to mock-treated cells at 2 hpi (Fig. 6E and F). These results show that neither depletion nor functional inhibition of transportin 1 has a major impact on adenoviral genome import. One possible explanation is that in the presence of Nup358 other import receptors can compensate for the lack of transportin 1 to promote import of the adenoviral genome into the nucleus. Alternatively, the remaining pool of transportin 1 is sufficient to drive genome import.

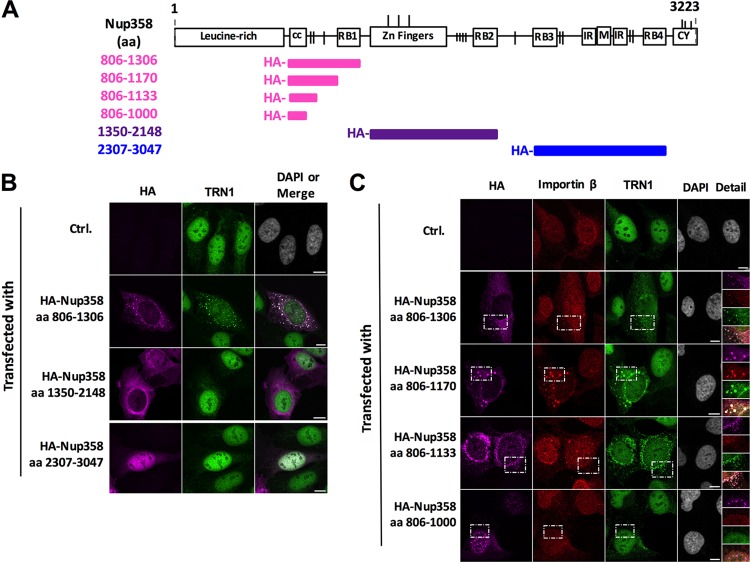

The N-terminal region of Nup358 recruits transport receptors.

Binding of transport receptors to FG repeats of nucleoporins is of low affinity and occurs transiently (34). In addition, RanGTP targets importin β to Nup358 via binding to the Ran-binding domains (RanBDs) (35, 36). To study the contribution of the different domains of Nup358 in the recruitment of transportin 1 (i.e., for adenoviral genome import), we first transfected cells with HA-tagged constructs coding for the following fragments of Nup358 lacking the NPC-anchoring region: Nup358(806–1306), comprising a coiled-coil region, a cluster of FG repeats and the first RanBD; Nup358(1350–2148), harboring several zinc fingers, another cluster of FG repeats, and the second RanBD; and Nup358(2307–3047), a C-terminal fragment, containing two FG-repeat clusters and RanBD-3 and RanBD-4 (Fig. 7A and B). The staining of endogenous transportin 1 was predominantly nuclear in control transfected cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, in cells expressing HA-Nup358(806–1306), endogenous transportin 1 was partially redistributed to the cytoplasm and colocalized with the soluble nucleoporin fragment. In contrast, redistribution of transportin 1 was not observed in cells expressing Nup358(1350–2148) or Nup358(2307–3047). These results suggest that only the soluble fragment comprising the first patch of FG repeats and RanBD-1 recruits endogenous transportin 1. They are in agreement with our observation that this region can rescue Ad5 genome import when linked to the N-terminal NPC-anchoring fragment of Nup358. In contrast, overexpression of the soluble fragment Nup358(806–1306) did not affect Ad5 genome import (data not shown), which was expected, as it was previously shown to compete with import of neither cNLS-containing nor M9-containing reporter constructs (27). We then asked whether this recruitment was specific for transportin 1 or would also be observed for another prominent import receptor, importin β. We also tried to further narrow the search for identification of the region in the Nup358(806–1306) fragment driving the recruitment. Cells were transfected with HA-tagged fragments of Nup358 [Nup358(806–1306), Nup358(806–1170), Nup358(806–1133), and Nup358(806–1000)] and stained for endogenous transportin 1 or importin β (Fig. 7C). Localization of endogenous transportin 1 and importin β was largely nuclear in control transfected cells (Fig. 7C, top row). Expression of the largest fragment (aa 806–1306) caused a relocalization of both transportin 1 and importin β to cytoplasmic structures colocalizing with the HA-tagged fragment. The fragment lacking RanBD-1 (aa 806–1170) was still able to relocalize both endogenous importins. HA-Nup358(806–1133) caused only a partial redistribution of importin β and transportin 1. Finally, the fragment containing exclusively the coiled-coiled domain of Nup358(806–1000) itself strongly located in the nucleus but did not relocate any of the transport receptors tested. These results show that the N-terminal region (aa 806–1306) of Nup358 encoding a cluster of FG repeats and RanBD-1 is able to recruit the prominent importins importin β and transportin 1. This observation is in line with a role of the N terminus of Nup358 in adenoviral genome import by concentrating transport receptors at the NPC.

FIG 7.

The soluble N-terminal FG repeats of Nup358 relocalize transportin 1 and importin β. (A) Schematic representation of the structure of Nup358. Soluble HA-tagged fragments of Nup358 used in this assay are represented in different colors, and the corresponding amino acid residues (aa) are indicated to the left of the horizontal bar representing each fragment. The N-terminal HA-epitope tag is indicated. (B) Representative maximum projection confocal images of endogenous transportin 1 (TRN1) distribution in U2OS cells transfected with an empty control plasmid (Ctrl.) or expressing HA-tagged soluble fragments of Nup358, as indicated to the left. Antibodies used to detect the HA tag of transfected Nup358 fragments (magenta) or endogenous TRN1 (green) are indicated above each column. Colocalization of HA-Nup358 fragments with endogenous TRN1 is shown in the right column as an overlay (white signal). Bars, 10 μm. (C) Experiment performed as described for panel B. Fragments are indicated to the left, and the antibodies used to detect the HA tag of transfected Nup358 fragments (magenta) or endogenous importin β (red) or endogenous TRN1 (green) are indicated above each column. The boxed area showing colocalization of HA-Nup358 fragments with endogenous TRN1 and importin β is shown in the right column as individual channels and overlay (white signal). Bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The cytoplasmic nucleoporins Nup214 and Nup358 have been implicated in key steps of adenoviral genome delivery, including capsid docking and disassembly to release the viral genome at the NPC, followed by nuclear import of the genome. Consensus has emerged over the role of Nup214 as a docking site for the adenoviral capsid at the NPC (19, 20, 23). In contrast, the role of Nup358 in adenoviral genome delivery is less clear. While one study showed that partial depletion of Nup358 does not affect adenoviral infection (20), a second study implicated Nup358 in capsid disassembly at the NPC to prepare the genome for import (23). The findings were in part based on the quantification of marker gene expression from delivered adenoviral vector genomes. However, analysis of adenoviral infection efficiencies does not allow discerning whether Nup358 depletion affects adenoviral genome delivery directly or rather affects indirect steps, e.g., those linked to marker gene expression. We used specific antibodies recognizing both genome-associated protein VII to detect the cargo (i.e., viral genomes) and the viral capsids in order to analyze kinetics of adenoviral genome delivery through direct observation and quantification. This approach allowed us to evaluate the relative proportions of disassembled capsids and released and imported genomes over time. We observed that specific depletion of Nup358 delayed accumulation of adenoviral genomes in the nucleus within the first 2 hpi. Importantly, this observation was made in different cell lines (U2OS and HeLa) using different methods for the depletion of Nup358 (siRNAs and shRNAs). At later time points, nuclear genome accumulation was not affected by Nup358 depletion. Our results suggest that Nup358 is not essential for but does facilitate adenoviral genome import. We further show that Nup358 does not impact the kinetic of capsid disassembly but rather drives nuclear import of viral genomes.

Previous studies demonstrated that depletion of Nup358 leads to reduced importin α/β-dependent and transportin 1-dependent protein import in HeLa cells and in conditional knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (6, 32, 35). Using different NPC-anchored fragments of Nup358, it was shown previously that the role of Nup358 in facilitating nuclear protein import was predominantly performed by the N-terminal region of Nup358, while its C-terminal half was dispensable (27, 35, 37). Here, we used a similar approach in Nup358-depleted U2OS cells to map the minimal region of Nup358 required to restore efficient adenoviral genome delivery. A relatively short fragment containing the N-terminal half of Nup358 was sufficient to restore Ad5 genome import to control levels. This minimal Nup358 fragment comprises the N terminus with a FG-repeat cluster, one RanBD, and the zinc finger domain. The C-terminal half of Nup358, in contrast, is not required for either Ad5 capsid disassembly or import of the viral genome into the nucleus. This was surprising, because it has been suggested that overexpression of the kinesin-1 binding domain of Nup358, JX2, which is downstream of the zinc finger region, reduces Ad2 infection by outcompeting capsid disassembly at the NPC involving capsid protein pIX (23). Our study of genome delivery for Ad5 lacking pIX (Fig. 4) suggested a role for pIX in capsid stabilization consistent with previous observations (28–30). We did not find, however, any evidence for pIX being required for capsid disassembly and genome import at the NPC.

Expression of exogenous transportin 1 and, to a lesser extent, importin 9 compensated for Nup358 depletion in Ad5 genome import, showing that transport receptors become rate limiting under depletion conditions. Similarly, in cells lacking Nup358, expression of exogenous transport receptors restored the defects observed in nuclear import of certain importin α/β-dependent and transportin 1-dependent cargoes (6, 32). Import of other cargoes was not promoted by an excess of transport receptors, suggesting that direct cargo-Nup358 interactions were required. Hence, Nup358 seems to stimulate nuclear import by at least two mechanisms: first, by increasing the active concentration of transport receptors at the NPC; second, by providing receptor-independent binding sites for selective cargoes (27). On the basis of our results, we favor a model where Nup358 serves as a platform for transport receptor binding and subsequent import complex formation, thereby promoting adenoviral genome import. For example, the N-terminal Nup358(1–1306) fragment, containing the first FG-repeat cluster and RanBD-1, was sufficient to restore cell viability and importin β-dependent import in MEFs (35). This is in line with our results showing genome import restoration via the N-terminal region of the nucleoporin and the observation that a short soluble fragment, Nup358(806–1306), but not other regions, efficiently recruits importin β and transportin 1. FG clusters in nucleoporins were previously shown to be involved in transport receptor binding (38, 39). The exact region of Nup358 serving as the docking site for transportin 1 is not known (40). However, an excess of transportin 1 was shown to inhibit importin α/β-dependent import, and vice versa, in digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells (41), suggesting that the two share similar docking sites at the cytoplasmic filaments of the NPC.

Although expression of exogenous transportin 1 upon Nup358 depletion restored nuclear import of Ad5 genomes, its depletion or functional inactivation did not significantly affect genome import. Insufficient depletion seems unlikely as we observed a very strong reduction of transportin levels (Fig. 5A). If transportin 1 binds to a specific site of Nup358 shared with other import receptors as our data suggest, it is more likely that depletion of transportin 1 liberates the site, giving room for other import receptors to promote import of adenoviral genomes. This is in line with previous work showing that adenoviral genome import is likely mediated by protein VII, which covers the DNA and possesses several NLSs that can be recognized by several import receptors (21, 22). Indeed, protein VII can form functional import complexes with transportin 1, importin β, and importin 7 (21, 22). Strikingly, only transportin 1 was limiting for adenoviral genome import in in vitro assays (22). In addition, transportin 1 and importin 7 mediated nuclear import of exogenous DNA in reconstituted Xenopus nuclei and in digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells, respectively (42, 43). Importin 9, which partially compensated for Nup358 depletion in adenoviral genome import, was not included in these studies but can mediate import of basic proteins such as cellular histones and the HIV-1 Rev protein, another viral nucleic acid adapter (32, 44). RanGTP-dependent binding of importin 7 to RanBD-1-containing or RanBD-2- and RanBD-3-containing regions of Nup358 has also been reported (37), while interactions between importin 9 and Nup358 remain to be investigated.

We propose that Nup358 and transport receptors cooperate in adenoviral genome delivery. The nucleoporin maintains a high level of importins close to the NPC via recruitment of free transport receptors (through FG-repeat binding) or in complex with RanGTP (through the RanBDs), rather than providing direct binding sites for adenoviral particles. Our results also show that transportin 1 is the most efficient transport receptor mediating import of adenoviral genomes in the absence of Nup358, suggesting that it is also the most relevant import receptor for adenoviral genomes in vivo. Thus, our findings support a model in which Nup358 facilitates adenoviral genome delivery through bound protein VII or other NLS-containing adapter molecules by maintaining high concentrations of available import receptors, preferentially transportin 1, near the NPC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HEK-293 αvβ5 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells [ATCC CRL-1573], kindly provided by G. Nemerow, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, USA), HeLa cells (ATCC CCL-2, kindly provided by L. Gerace, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, USA), and U2OS cells (human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cells [ATCC HTB-96], kindly provided by M. Piechaczyk, IGMM, Montpellier, France) were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 at 37°C, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen). When indicated, cells were treated with 20 nM LMB (Sigma) for 30 min and then infected in the presence of 20 nM LMB.

Transient transfection of DNA.

U2OS cells were seeded to reach ∼60% to 80% confluence on the day of transfection. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 and Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). To increase transfection efficiency of large constructs (e.g., constructs encoding long HA-tagged NPC-anchored fragments of Nup358), cells were treated with 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) DMEM for 2 min and then gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to transfection.

Plasmids.

Constructs coding for GFP2-M9 core and GFP2-cNLS (5), myc-MBP-M9M (27), HA-importin β and HA-transportin 1 (6), HA-importin 7 (37), HA-importin 9 (32), and HA-CRM1 C528S (45) and constructs coding for HA-tagged full-length Nup358 and its fragments (27) were described previously. A pcDNA3.1+ empty vector was purchased from Invitrogen and used as a DNA control.

RNA interference.

U2OS were seeded in a 12-well plate (105 cells/well). The next day, cells were transfected with 100 nM siRNA per condition using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In the case of Nup358 depletion/restitution experiments, a DNA-siRNA cotransfection of the Nup358 constructs with specific or nontargeting siRNAs was performed 48 h after the first siRNA depletion using the protocol for transient transfection. Seventy-two hours after the first siRNA depletion, cells were infected or directly fixed for further analysis. Validated siRNA oligonucleotides directed against the mRNA of Nup358 5′-CACAGACAAAGCCGUUGAA as described previously (27) or nonspecific 5′-AGGUAGUGUAAUCGCCUUG were obtained from Eurofins Genomics. siRNAs for the depletion of transportin were obtained from Santa Cruz (sc-35737) (32). Efficient depletion of both Nup358 and transportin 1 was monitored by immunofluorescence and reached a maximum 72 h after siRNA transfection. Gene silencing of Nup358 by the use of shRNA was done as previously described (20). Cells were transfected with pSUPER vector (Oligoengine) expressing shRNA directed against Nup358 (5′-GATCCCCCGAGGTCAATGGCAAACTATTCAAGAGATAGTTTGCCATTGACCTCGTTTTTA-3′) or with a peGFP-H1 vector containing two expression cassettes, one for enhanced GFP (eGFP) and one for nontargeting shRNA, as a control. An efficient knockdown of Nup358 was obtained 3 days after DNA transfection.

Virus production.

Amplification of replication-deficient E1-deleted GFP-expressing vectors based on genotypes HAdV-C5, Ad5-wt-GFP (46), and Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP (kindly provided by Christopher M. Wiethoff, Stritch School of Medicine, IL, USA) was done in HEK293-αvβ5 cells, and the resulting mixture was purified using double CsCl2 banding (12, 46). Viruses were labeled by using an Alexa Fluor microscale labeling kit (Life Technologies) as detailed previously (47). Viral physical particle quantification was performed on the basis of the estimated copy numbers of viral genomes. Copy numbers were calculated according to the optical density at 260 (OD260) method (OD260 of 1 = 1.16 × 1012 particles/ml) (48). The number of infectious particles was quantified by plaque assay. The viral titer of the stock sample was determined by taking the average number of GFP-fluorescent plaques for a dilution and the inverse of the total dilution factor.

Viral infection and immunofluorescence (IF) staining.

Cells grown on 15-mm-diameter coverslips in a 12-well plate were seeded in order to have 1.5 × 105 to 2 × 105 cells the day of infection. For analysis of kinetic of adenoviral genome delivery, a time course infection was performed using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 and the Ad5-wt-GFP. Comparing different viruses (Ad5-wt-GFP versus Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP), a total of 5,000 pancreatic polypeptides (pp)/cell were used for infections. Time course infection was performed with 5,000 pp/cell for analysis of endosomal escape of Ad5 particles. In all cases, the number of internalized particles per cell at the time of analysis was in the range of 50 to 150. Viruses were diluted in prewarmed DMEM (100 μl/condition) (37°C) and added to cells for 30 min to allow Ad5 particle binding and internalization. After 30 min, the inoculum was removed; this was considered time point zero. Coverslips were incubated in 1 ml/well fresh prewarmed (37°C) DMEM and fixed at different time points using 4% paraformaldehyde (pH = 7.4). Cells were blocked/permeabilized using IF buffer (10% fetal calf serum [FCS]–0.5% saponin–PBS). Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in IF buffer and applied to cells for 1 h in a humid chamber at 37°C. Cells were mounted using fluorescence mounting medium (Dako) containing 1 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma) to visualize the cellular DNA and were analyzed by microscopy.

Antibodies.

The following antibodies used for IF in this study: serum of rabbit anti-HAd5-C5, dilution 1:1000 (kindly provided by R. Iggo, Institut Bergonie, Bordeaux, France); mouse anti-protein VI, dilution 1:400 (46); mouse anti-protein VII, dilution 1:100 (49); rat anti-protein VII, dilution 1:500 (50); mouse anti-human transportin 1, dilution 1:500 (BD Bioscience); rabbit anti-importin β, dilution 1:500; rabbit anti-human Nup358 (aa 3062 to 3223), goat anti-human Nup358 (aa 2553 to 2838) (8), both diluted 1:1,000; goat anti-human CRM1 (51), dilution 1:250; mouse anti-Myc tag, dilution 1:400 (Molecular Probes); rat anti-HA tag, dilution 1:500 (Roche); rabbit anti-RanBP1, dilution 1:250 (kindly provided by L. Gerace, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, USA). Secondary antibodies from donkey coupled with Alexa fluor were used at a dilution of 1:500 (Life Technologies). Antibodies used for Western blotting in this study were as follows: rabbit anti-chicken α-tubulin (Sigma), dilution 1:1,000; mouse anti-human transportin 1, dilution 1:1,000 (BD Bioscience); peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research) diluted 1:10,000.

Confocal microscopy and image analysis.

Immunofluorescence preparations were imaged using confocal SP5 or SP8-CRYO microscopes (Leica) equipped with Leica software on the Bordeaux Imaging Center (BIC) platform. Confocal stacks (∼10 stacks) were taken every 0.3 μm with a pinhole setting of 1, using 3-fold oversampling for all channels. Images were acquired with settings of a resolution of 16 bits and a pixel size of 75 nm. Images were processed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health). Stacks from the channel of interest (e.g., fluorescence of Nup358) of confocal images were combined as Z-projections. Individual cells were selected from maximal-projection images by drawing a selection around the cell periphery. Individual cells were used for single signal quantifications. A threshold was applied to identify the area considered representative of positive signal in a given channel of interest (e.g., that corresponding to the fluorescence of DAPI to delineate the area of the nucleus and to the fluorescence of pVII to identify and quantify genomes within the DAPI area). Objects from binary images were quantified when their sizes exceeded a defined area of pixels (10 pixels for pVII and 5 pixels for Ad5 capsids). For quantification of colocalization between signals, superposition of two binary images from two channels of interest was used. Objects exceeding a defined area of pixels in common were quantified. The result of these quantifications gives the number of objects for each region of interest (for each cell). A semiautomated macro was developed to perform quantifications of all images. In the case of quantification of fluorescence intensity, a threshold was applied to highlight the area considered to represent positive signal for the control condition. The integrated density in the thresholded area for each one of the regions of interest (for each cell) was quantified. A macro was developed to automate quantifications of all images with settings resembling those for control cells.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software. Results are presented either in a scatterplot or in columns, as indicated in the figure legends. Bars indicate the standard deviations (SD). Horizontal lines or the lengths of the columns represent means. To compare the means of results from two populations, statistical analysis was done using unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. To compare the means of results from three or more sets of conditions, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (one factor) or two-way ANOVA (two factors) was applied, as indicated in the figure legends. Multicomparison post hoc corrections were performed to figure out which groups in the sample differed. In the case of the one-way ANOVA post hoc tests, Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was used when the sample sizes of groups were equal; otherwise, Dunnett’s test was used. In the case of two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s correction was used for multicomparison tests (NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

Western blotting.

Cells were harvested using 0.6 mM EDTA–PBS, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and cocktail protease inhibitors (cOmplete, mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations in the cell extracts were quantified by Bio-Rad protein assay (52). Clarified cell extracts were diluted in Laemmli 4× buffer (8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 200 mM Tris buffer, pH 6.8) and boiled at 95°C for 15 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using an ECL Femto kit (Millipore) and an ImageQuant LAS 4010 imaging system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Iggo, F. Melchior, and L. Gerace for kind gifts of antibodies; G. Nemerow and M. Piechaczyk for providing cell lines; and C. M. Wiethoff for providing the Ad5-ΔpIX-GFP virus. Microscopy was done in the Bordeaux Imaging Center, a service unit of the CNRS INSERM and Bordeaux University, a member of the national infrastructure France BioImaging.

This work was supported in part through Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) grant DEQ20180339229 (H.W.), a Ph.D. cotutelle grant from the Excellence Initiative (IdEX) of Bordeaux University (F.L.), and grant KE 660/16-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (R.H.K.). The funders had no influence in study design, data collection or interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. H.W. is an INSERM fellow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin DH, Hoelz A. 2019. The structure of the nuclear pore complex (an update). Annu Rev Biochem 88:725–783. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-011901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickmanns A, Kehlenbach RH, Fahrenkrog B. 2015. Nuclear pore complexes and nucleocytoplasmic transport: from structure to function to disease. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 320:171–233. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panté N, Kann M. 2002. Nuclear pore complex is able to transport macromolecules with diameters of about 39 nm. Mol Biol Cell 13:425–434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried H, Kutay U. 2003. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: taking an inventory. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:1659–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutten S, Kehlenbach RH. 2006. Nup214 is required for CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 26:6772–6785. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00342-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutten S, Flotho A, Melchior F, Kehlenbach RH. 2008. The Nup358-RanGAP complex is required for efficient importin α/β-dependent nuclear import. Mol Biol Cell 19:2300–2310. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-12-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritterhoff T, Das H, Hofhaus G, Schröder RR, Flotho A, Melchior F. 2016. The RanBP2/RanGAP1*SUMO1/Ubc9 SUMO E3 ligase is a disassembly machine for Crm1-dependent nuclear export complexes. Nat Commun 7:11482. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pichler A, Gast A, Seeler JS, Dejean A, Melchior F. 2002. The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 108:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00633-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Y, Singh BB, Aslanukov A, Zhao H, Ferreira PA. 2001. The docking of kinesins, KIF5B and KIF5C, to Ran-binding protein 2 (RanBP2) is mediated via a novel RanBP2 domain. J Biol Chem 276:41594–41602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathinam VAK, Fitzgerald KA. 2011. Innate immune sensing of DNA viruses. Virology 411:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung MT, Cao TM, Coleman RT, Budelier KA. 1983. Gene and protein sequences of adenovirus protein VII, a hybrid basic chromosomal protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80:2902–2906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wodrich H, Henaff D, Jammart B, Segura-Morales C, Seelmeir S, Coux O, Ruzsics Z, Wiethoff CM, Kremer EJ. 2010. A capsid-encoded PPxY-motif facilitates adenovirus entry. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000808. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montespan C, Marvin SA, Austin S, Burrage AM, Roger B, Rayne F, Faure M, Campell EM, Schneider C, Reimer R, Grünewald K, Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H. 2017. Multi-layered control of Galectin-8 mediated autophagy during adenovirus cell entry through a conserved PPxY motif in the viral capsid. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR. 2005. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J Virol 79:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.1992-2000.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindert S, Silvestry M, Mullen T-M, Nemerow GR, Stewart PL. 2009. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of an adenovirus-integrin complex indicates conformational changes in both penton base and integrin. J Virol 83:11491–11501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01214-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strunze S, Trotman LC, Boucke K, Greber UF. 2005. Nuclear targeting of adenovirus type 2 requires CRM1-mediated nuclear export. Mol Biol Cell 16:2999–3009. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-02-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JG, Cassany A, Gerace L, Ralston R, Nemerow GR. 2008. Neutralizing antibody blocks adenovirus infection by arresting microtubule-dependent cytoplasmic transport. J Virol 82:6492–6500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00557-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang I-H, Burckhardt CJ, Yakimovich A, Morf MK, Greber UF. 2017. The nuclear export factor CRM1 controls juxta-nuclear microtubule-dependent virus transport. J Cell Sci 130:2185–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.203794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotman LC, Mosberger N, Fornerod M, Stidwill RP, Greber UF. 2001. Import of adenovirus DNA involves the nuclear pore complex receptor CAN/Nup214 and histone H1. Nat Cell Biol 3:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassany A, Ragues J, Guan T, Bégu D, Wodrich H, Kann M, Nemerow GR, Gerace L. 19 November 2014, posting date Nuclear import of adenovirus DNA involves direct interaction of hexon with an N-terminal domain of the nucleoporin Nup214. J Virol 89:e02639-14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02639-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wodrich H, Cassany A, D'Angelo MA, Guan T, Nemerow G, Gerace L. 2006. Adenovirus core protein pVII is translocated into the nucleus by multiple import receptor pathways. J Virol 80:9608–9618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00850-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hindley CE, Lawrence FJ, Matthews DA. 2007. A role for transportin in the nuclear import of adenovirus core proteins and DNA. Traffic 8:1313–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strunze S, Engelke MF, Wang I-H, Puntener D, Boucke K, Schleich S, Way M, Schoenenberger P, Burckhardt CJ, Greber UF. 2011. Kinesin-1-mediated capsid disassembly and disruption of the nuclear pore complex promote virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 10:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer M, Flatt JW, Seiler D, Cardel B, Emmenlauer M, Boucke K, Suomalainen M, Hemmi S, Greber UF. 2019. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Mind Bomb 1 controls adenovirus genome release at the nuclear pore complex. Cell Rep 29:3785–3795.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komatsu T, Quentin-Froignant C, Carlon-Andres I, Lagadec F, Rayne F, Ragues J, Kehlenbach RH, Zhang W, Ehrhardt A, Bystricky K, Morin R, Lagarde J-M, Gallardo F, Wodrich H. 2018. In vivo labelling of adenovirus DNA identifies chromatin anchoring and biphasic genome replication. J Virol 92:e00795-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00795-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang I-H, Suomalainen M, Andriasyan V, Kilcher S, Mercer J, Neef A, Luedtke NW, Greber UF. 2013. Tracking viral genomes in host cells at single-molecule resolution. Cell Host Microbe 14:468–480. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wälde S, Thakar K, Hutten S, Spillner C, Nath A, Rothbauer U, Wiemann S, Kehlenbach RH. 2012. The nucleoporin Nup358/RanBP2 promotes nuclear import in a cargo- and transport receptor-specific manner. Traffic 13:218–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosa-Calatrava M, Grave L, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Chatton B, Kedinger C. 2001. Functional analysis of adenovirus protein IX identifies domains involved in capsid stability, transcriptional activity, and nuclear reorganization. J Virol 75:7131–7141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7131-7141.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colby WW, Shenk T. 1981. Adenovirus type 5 virions can be assembled in vivo in the absence of detectable polypeptide IX. J Virol 39:977–980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.39.3.977-980.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furcinitti PS, van Oostrum J, Burnett RM. 1989. Adenovirus polypeptide IX revealed as capsid cement by difference images from electron microscopy and crystallography. EMBO J 8:3563–3570. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kudo N, Matsumori N, Taoka H, Fujiwara D, Schreiner EP, Wolff B, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S. 1999. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:9112–9117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutten S, Wälde S, Spillner C, Hauber J, Kehlenbach RH. 2009. The nuclear pore component Nup358 promotes transportin-dependent nuclear import. J Cell Sci 122:1100–1110. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cansizoglu AE, Lee BJ, Zhang ZC, Fontoura BMA, Chook YM. 2007. Structure-based design of a pathway-specific nuclear import inhibitor. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14:452–454. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aramburu IV, Lemke EA. 2017. Floppy but not sloppy: interaction mechanism of FG-nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 68:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamada M, Haeger A, Jeganathan KB, van Ree JH, Malureanu L, Wälde S, Joseph J, Kehlenbach RH, van Deursen JM. 2011. Ran-dependent docking of importin-beta to RanBP2/Nup358 filaments is essential for protein import and cell viability. J Cell Biol 194:597–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delphin C, Guan T, Melchior F, Gerace L. 1997. RanGTP targets p97 to RanBP2, a filamentous protein localized at the cytoplasmic periphery of the nuclear pore complex. Mol Biol Cell 8:2379–2390. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frohnert C, Hutten S, Wälde S, Nath A, Kehlenbach RH. 2014. Importin 7 and Nup358 promote nuclear import of the protein component of human telomerase. PLoS One 9:e88887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rexach M, Blobel G. 1995. Protein import into nuclei: association and dissociation reactions involving transport substrate, transport factors, and nucleoporins. Cell 83:683–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Port SA, Monecke T, Dickmanns A, Spillner C, Hofele R, Urlaub H, Ficner R, Kehlenbach RH. 2015. Structural and functional characterization of CRM1-Nup214 interactions reveals multiple FG-binding sites involved in nuclear export. Cell Rep 13:690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau CK, Delmar VA, Chan RC, Phung Q, Bernis C, Fichtman B, Rasala BA, Forbes DJ. 2009. Transportin regulates major mitotic assembly events: from spindle to nuclear pore assembly. Mol Biol Cell 20:4043–4058. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e09-02-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonifaci N, Moroianu J, Radu A, Blobel G. 1997. Karyopherin beta2 mediates nuclear import of a mRNA binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:5055–5060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lachish-Zalait A, Lau CK, Fichtman B, Zimmerman E, Harel A, Gaylord MR, Forbes DJ, Elbaum M. 2009. Transportin mediates nuclear entry of DNA in vertebrate systems. Traffic 10:1414–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhanoya A, Wang T, Keshavarz-Moore E, Fassati A, Chain BM. 2013. Importin-7 mediates nuclear trafficking of DNA in mammalian cells. Traffic 14:165–175. doi: 10.1111/tra.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mühlhäusser P, Müller E-C, Otto A, Kutay U. 2001. Multiple pathways contribute to nuclear import of core histones. EMBO Rep 2:690–696. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hilliard M, Frohnert C, Spillner C, Marcone S, Nath A, Lampe T, Fitzgerald DJ, Kehlenbach RH. 2010. The anti-inflammatory prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 inhibits CRM1-dependent nuclear protein export. J Biol Chem 285:22202–22210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez R, Schellenberger P, Vasishtan D, Aknin C, Austin S, Dacheux D, Rayne F, Siebert A, Ruzsics Z, Gruenewald K, Wodrich H. 2015. The amphipathic helix of adenovirus capsid protein VI contributes to penton release and postentry sorting. J Virol 89:2121–2135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02257-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez R, Burrage AM, Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H. 2013. High temporal resolution imaging reveals endosomal membrane penetration and escape of adenoviruses in real time. Methods Mol Biol 1064:211–226. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-601-6_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittereder N, March KL, Trapnell BC. 1996. Evaluation of the concentration and bioactivity of adenovirus vectors for gene therapy. J Virol 70:7498–7509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.70.11.7498-7509.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komatsu T, Dacheux D, Kreppel F, Nagata K, Wodrich H. 2015. A method for visualization of incoming adenovirus chromatin complexes in fixed and living cells. PLoS One 10:e0137102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haruki H, Gyurcsik B, Okuwaki M, Nagata K. 2003. Ternary complex formation between DNA-adenovirus core protein VII and TAF-Ibeta/SET, an acidic molecular chaperone. FEBS Lett 555:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roloff S, Spillner C, Kehlenbach RH. 2013. Several phenylalanine-glycine motives in the nucleoporin Nup214 are essential for binding of the nuclear export receptor CRM1. J Biol Chem 288:3952–3963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]