Abstract

Background

In developed countries, colon cancer is a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality. Dietary changes have resulted in an increased incidence of colon cancer in Asia. This study aimed to investigate the effects of the structural analog of endomorphin-2 (H-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2) on human colon cancer cells in vitro.

Material/Methods

Human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells and CCD-18Co normal human colonic fibroblasts were treated with increasing doses of the structural analog of endomorphin-2. Cells underwent the MTT assay, fluorescence confocal flow cytometry, and Hoechst 33258 staining to investigate cell proliferation, the cell cycle, and apoptosis. Western blot was used to measure the expression levels of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), cytochrome c, caspase-3, and caspase-9. The 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescence method measured reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Results

Cell proliferation of DLD-1 and RKO cells was inhibited by the endomorphin-2 analog in a dose-dependent manner, and a 100 μM dose reduced DLD-1 and RKO cell proliferation by 28% and 23%, respectively, at 72 h. Endomorphin-2 analog induced cell apoptosis and the generation of ROS, activated caspase-3 and caspase-9, and increased the levels of p53 and cytochrome c release, and down-regulated of Akt activation in DLD-1 and RKO cells in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment of the DLD-1 and RKO cells with the endomorphin-2 analog increased the expression of Bax and reduced the expression of Bcl-2.

Conclusions

Endomorphin-2 analog inhibited colon cancer cell proliferation, activated apoptosis, and down-regulated Akt phosphorylation of human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells in vitro in a dose-dependent manner.

MeSH Keywords: Apoptosis, Chromatin Assembly and Disassembly, Lymphatic Metastasis

Background

In developed countries, colon cancer is a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality [1,2]. The incidence of colon cancer has been found to increase during the past decade, and it ranks as the third highest malignant tumor [3]. Local invasion by colon carcinoma cells results in metastasis that results in a high mortality rate [3]. Treatment of colon cancer includes surgical resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy [4–6]. The diagnosis of early-stage colon cancer before the occurrence of metastases is associated with improved prognosis [7]. Postoperative recovery for patients with early-stage colon cancer is reduced, and the 5-year survival rate is higher than 55% [8]. However, patients with advanced-stage colon cancer with metastasis to the lymph nodes, lungs, and liver have a 5-year survival rate of less than 20% [9].

Cell apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a regulated mechanism for the elimination of cells that occurs during development and in human disease [10]. Cells that undergo apoptosis show distinct morphological changes that include cell and nuclear shrinkage, imbalance in mitochondrial membrane potential, and chromatin condensation, and chromatin fragmentation [10,11]. The mechanism of induction of apoptosis in cancer cells involves extrinsic and intrinsic pathways [12]. In the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis, the signals received by cell receptors on the cell surface activate caspase-8 [13]. However, apoptosis that occurs through the intrinsic pathway is activated by caspase-3 and caspase-9, and is associated with an increase in the Bax and Bcl-2 ratio [13]. During chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy of cancer, malignant cells destroyed through the activation of apoptosis [14,15].

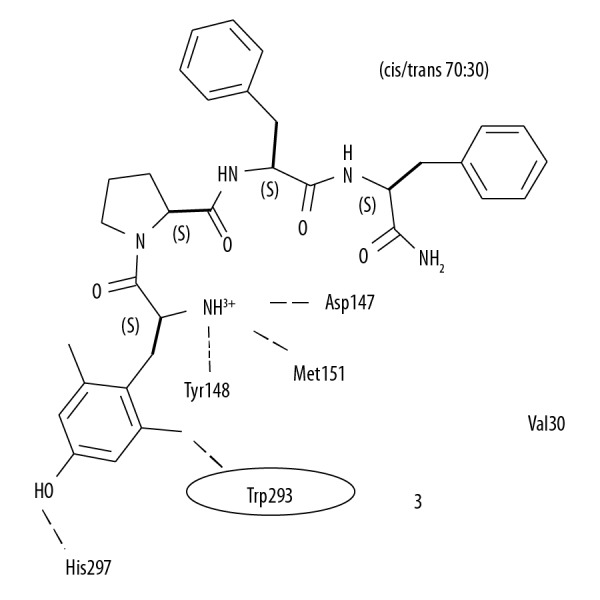

Opioid growth factor receptors have been well characterized in human tumors and animal and in vitro models [16,17]. The opioid receptor and growth factor axis are active pathways that have been targeted using small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology to enhance cell proliferation [16,18]. In 2011, Donahue et al. reported that in a mouse model, low-dose naltrexone inhibited the growth of tumor xenografts when combined with cisplatin [19]. In 2013, Zagon et al. reported the involvement of the opioid growth factor and opioid growth factor receptor axis in the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation of triple-negative breast cancer cells [20]. Opioid peptides, including endorphin and endomorphin-2, which are used in the management of pain and other symptoms, may be modified and used as derivatives and analogs [21–23]. A structural analog of endomorphin-2 (H-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2) includes structural modification of tyrosine in position 1, which results in increased receptor affinity for opioid receptors (Figure 1) [24]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of the structural analog of endomorphin-2 on human colon cancer cells in vitro.

Figure 1.

A diagram of the structural analog of endomorphin-2 (H-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2) with structural modification of tyrosine in position 1 that may increase receptor affinity.

Material and Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Cell lines studied included CCD-18Co normal human colonic fibroblasts, and human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells, which were supplied by the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cellular Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

MTT cell viability assay

The changes in CCD-18Co, RKO, and DLD-1 cell proliferation following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog were determined using the MTT assay. Cells were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates at a density of 2×105/ml for 24 h. The cells were incubated with 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog for 48 h. Then, 20 μl of MTT solution was added to the plates. After 4 h of incubation, 100 μl of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the plates. Absorbance was measured at 575 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, μQuant, Toronto, ON, Canada). The measurements were performed in triplicate.

Fluorescence microscopy of the cell nuclear change

The nuclear changes in DLD-1 cells, following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog, were analyzed using Hoechst 33258 nuclear staining. After treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog for 48 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and then fixed for 15 min with 4% formaldehyde at 4°C and washed with PBS. Cell staining was performed at room temperature with Hoechst 33258 solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 15 min. The cell nuclei were examined using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-s fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of the cell cycle

DLD-1 cells were distributed in 6-well plates at 2×105 cells/ml and incubated for 48 h with 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog. The cells were harvested and then re-suspended in 300 μl of PBS. The cells were stained using a 5 μM solution of propidium iodide (PI) and RNase (50 μg) at room temperature for 45 min in the dark. The phases of the cell cycle were assessed by detection of the DNA content using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Flow cytometry for cell apoptosis

DLD-1 cells at a concentration of 2×105 cells/ml were treated for 48 h with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog. The cells were harvested and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. The cells were treated with 150 μl of binding buffer and incubated for 20 min with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and PI at room temperature in the dark. Apoptosis in the treated cells was analyzed using a Quanta SC flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA).

Western blot

DLD-1 cells were incubated with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog for 48 h. The proteins were extracted from DLD-1 cells using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) mixed with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The protein concentration in the lysates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The protein samples were loaded onto 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked by incubation with 5% dried skimmed milk powder diluted in tris-buffered saline (TBS) and Tween 20 (TBST).

The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in the following primary antibodies to: Akt, p-Akt, Bcl-2, Bax, p53, cytochrome c, pro-caspase-3, ro-caspase-9, PARP-1, and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). The membranes were washed in PBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. An electrochemiluminescence (ECL(detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, Bucks, UK) was used to visualize the bands. The bands were scanned using the ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Image acquisition and analysis were performed using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The generation of ROS in DLD-1 cells following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog was determined by flow cytometry using the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). The cells at a density of 2×105 cells/well were treated with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog for 48 h in six-well plates. After incubation, the cells were harvested and washed three times with PBS. The cells were then re-suspended and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in PBS containing DCFH-DA. The production of ROS in DLD-1 cells was analyzed using a FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Data analysis was performed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed independently in triplicate. The differences were compared using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

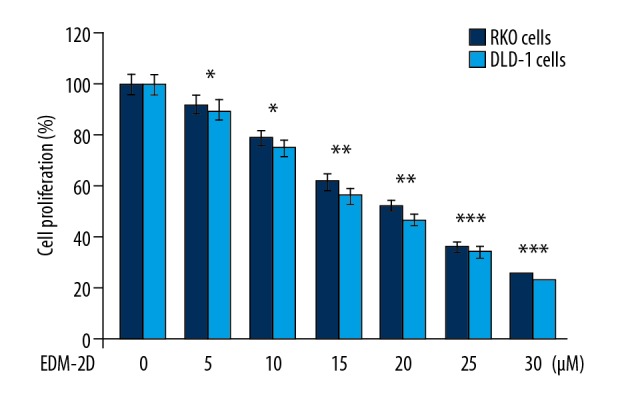

Endomorphin-2 analog reduced cell proliferation of the RKO and DLD-1 human colon carcinoma cells

Changes in the proliferation of normal CCD-18Co control cells, and RKO and DLD-1 human colon carcinoma cells following treatment with endomorphin-2 analog were analyzed by the MTT assay (Figure 2). The endomorphin-2 analog was added to cell cultures at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μM, and cell proliferation was examined at 48 h of treatment. There was no significant change in CCD-18Co cell proliferation following treatment (data not shown). There was a significant reduction in the proliferation of RKO and DLD-1 cells following endomorphin-2 analog treatment (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on the proliferation of DLD-1 and RKO human colon cancer cells. The MTT assay analyzed cells treated with endomorphin-2 analog at 48 h. * p<0.05, ** p<0.02, and *** p<0.01, compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

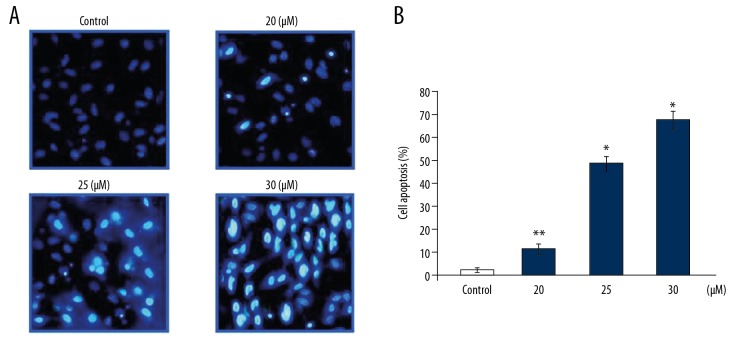

Endomorphin-2 analog induced nuclear changes in DLD-1 cells

The nuclei of DLD-1 cells at 48 h following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog were examined using Hoechst 33258 staining (Figure 3). Endomorphin-2 analog treatment at 20, 25, and 30 μM induced significant changes in DLD-1 cell nuclei, consistent with nuclear apoptotic changes.

Figure 3.

The effect of the endomorphin-2 analog on DLD-1 human colon cancer cell nuclei. (A) The cells treated with the endomorphin-2 analog at 20, 25, and 30 μM for 48 h were examined using Hoechst 33258 staining and flow cytometry. (B) The data on DLD-1 cells are presented compared with the control cells. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.02 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

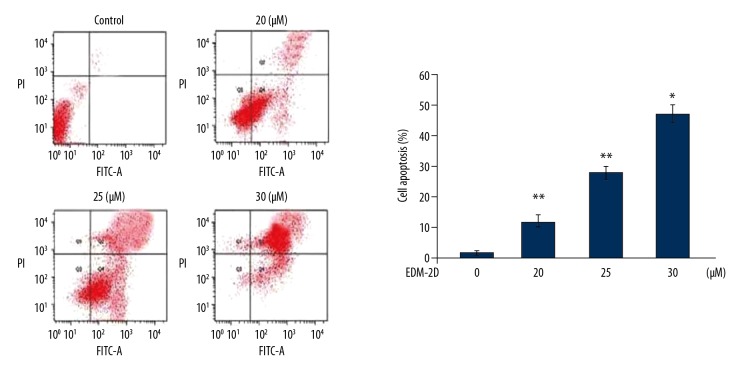

Endomorphin-2 analog induced apoptosis in DLD-1 cells

Annexin V- fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to examine apoptosis in DLD-1 cells following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog at 20, 25, and 30 μM, which significantly increased apoptosis when compared with the CCD-18Co control cells (Figure 4). In DLD-1 cell cultures treated with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog, the proportion of apoptotic cells increased to 12.34%, 27.85%, and 46.89%, respectively.

Figure 4.

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on cell apoptosis in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. Apoptotic changes following treatment of DLD-1 cells with the endomorphin-2 analog were measured by Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) double-staining. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

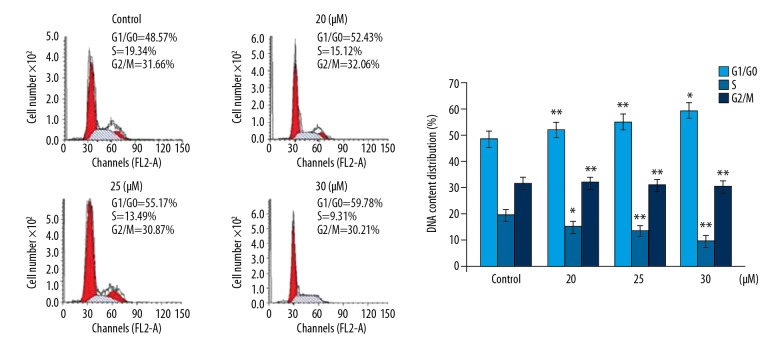

Endomorphin-2 analog arrested the cell cycle in DLD-1 cells

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on cell cycle in DLD-1 cells was examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with PI and Annexin V-FITC/PI staining (Figure 5). Treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog significantly increased the cell population in the G1/G0 phase. The DLD-1 cell population in the S-phase of the cell cycle was significantly reduced following treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog. These findings showed that endomorphin-2 analog inhibited the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase in DLD-1 cells.

Figure 5.

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on the cell cycle in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. The changes in cell cycle by endomorphin-2 analog in DLD-1 cells were measured using flow cytometry. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.02 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

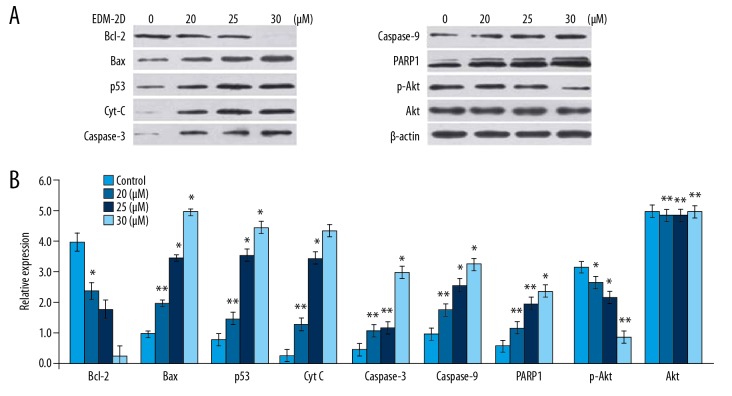

Endomorphin-2 analog increased the expression of apoptotic proteins in DLD-1 cells

Treatment of DLD-1 cells with the endomorphin-2 analog at 20, 25, and 30 μM reduced the expression of Bcl-2 and increased the expression of Bax in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6). The cells treated with the endomorphin-2 analog showed a significant increase in p53, cytochrome c, pro-caspase-3, and pro-caspase-9 expression at 48 h. The cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) was also promoted by endomorphin-2 analog treatment in DLD-1 cells. Treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog reduced the expression of p-Akt without any change in the levels of Akt.

Figure 6.

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on the expression of apoptotic cell proteins in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. (A) The cells treated with 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog were analyzed by Western blot. (B) Densitometric analysis of the data. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.02 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

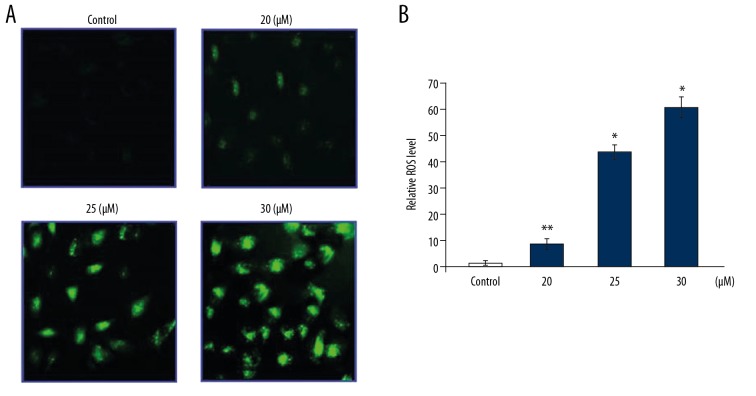

Endomorphin-2 analog increased the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in DLD-1 cells

The generation of ROS in DLD-1 cells following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog at 48 h was measured using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescence (Figure 7). Treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of the endomorphin-2 analog significantly increased ROS generation when compared with the control.

Figure 7.

The effect of endomorphin-2 analog on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. The cells were treated with endomorphin-2 analog and stained with fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) at 48 h. (A) The ROS level was measured by flow cytometry. (B) The data were quantified. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.02 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells. Data were quantified by FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

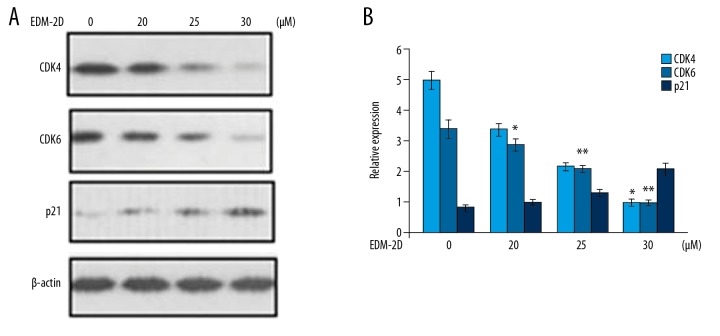

Endomorphin-2 analog suppressed CDK1, CDK6, and promoted p21 expression in DLD-1 cells

The levels of CDK1, CDK6, and p21 in DLD-1 cells treated with the endomorphin-2 analog at 48 h were assessed using Western blot (Figure 8). Treatment with 20, 25, and 30 μM of endomorphin-2 analog significantly increased p21 expression and reduced CDK1 and CDK6 expression at 30 μM, when compared with the control.

Figure 8.

Effect of the endomorphin-2 analog on cell cycle proteins in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. (A) The endomorphin-2 analog treated cells were assessed for cyclin proteins at 48 h by Western blot. (B) The data were quantified. * p<0.05 and ** p<0.02 compared with the CCD-18Co control cells.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects of the endomorphin-2 analog on colon cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis in vitro. The development of a structural analog of endomorphin-2 (H-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2) contained tyrosine in the sequence in position 1, which resulted in a compound that was more lipophilic and had increased affinity for opioid receptors [25,26]. The structural analog of endomorphin-2 was used at increasing doses to treat human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells and CCD-18Co normal human colonic fibroblasts. The findings showed that the endomorphin-2 analog inhibited colon cancer cell proliferation, activated cell apoptosis, and down-regulated Akt phosphorylation of human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells in vitro in a dose-dependent manner.

In mammalian cells, mitochondria have a vital role in inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation [27–29]. The early stage of apoptosis is characterized by disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is followed by the efflux of apoptotic factors from mitochondria and activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 [30–33]. In the present study, treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog resulted in a specific inhibitory effect on the proliferation of RKO and DLD-1 colon cancer cells, without affecting the CCD-18Co normal cells. These findings indicated that the endomorphin-2 analog had activity against human colon cancer cells in vitro.

In the present study, the mechanism of the activity against cancer cells in vitro of the endomorphin-2 analog was studied using the flow cytometry with Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) double-staining. The findings showed that treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog significantly enhanced the proportion of apoptotic cells in DLD-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner. In DLD-1 cells, the changes in the cell morphology induced by the endomorphin-2 analog included condensation of nuclear chromatin, cleavage of the cell membrane, and the formation of apoptotic bodies. Increased expression and integrity of Bax in the mitochondrial membranes have a vital role in enabling cells to undergo apoptosis [34]. Bcl-2 is present in the membranes of mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum and prevents the induction of apoptosis by quenching the free radicals generated in the cells [35,36].

The induction of apoptosis in carcinoma cells following treatment with anti-cancer agents is associated with an increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio [37,38]. In the present study, treatment of DLD-1 human colon cancer cells with the endomorphin-2 analog significantly increased the expression of Bax in a dose-dependent manner and reduced the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2. These findings supported that the endomorphin-2 analog increased the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in DLD-1 cells.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in signaling pathways that induce cell apoptosis and result in mitochondrial damage [39–42]. The present study measured ROS generation in DLD-1 cells following treatment with the endomorphin-2 analog, which significantly upregulated the production of ROS. Activation of Akt (serine/threonine-protein kinase) by phosphorylation enables cells to escape apoptosis [43]. Akt activation promotes the expression of FLICE inhibitory protein (FLIP), which inhibits the activity of caspase-8 [44]. In the present study, the treatment of DLD-1 human colon cancer cells with the endomorphin-2 analog significantly inhibited the expression of p-Akt.

Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the effects of the structural analog of endomorphin-2 (H-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2) on human colon cancer cells in vitro. The endomorphin-2 analog inhibited colon cancer cell proliferation, activated apoptosis, and down-regulated Akt phosphorylation of human DLD-1 and RKO colon cancer cells in vitro in a dose-dependent manner.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Chen Y, Fang L, Li G, et al. Synergistic inhibition of colon cancer growth by the combination of methylglyoxal and silencing of glyoxalase I mediated by the STAT1 pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:54838–57. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chino XMS, Martinez CJ, Garzón VRV, et al. Cooked chickpea consumption inhibits colon carcinogenesis in mice induced with azoxymethane and dextran sulfate sodium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:391–98. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2017.1297744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cusimano A, Balasus D, Azzolina A, et al. Oleocanthal exerts antitumor effects on human liver and colon cancer cells through ROS generation. Int J Oncol. 2017;51:533–44. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho N, Ransom TT, Sigmund J, et al. Growth inhibition of colon cancer and melanoma cells by versiol derivatives from a Paraconiothyrium species. J Nat Prod. 2017;80:2037–44. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myint ZW, Goel G. Role of modern immunotherapy in gastrointestinal malignancies: A review of current clinical progress. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:86. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goel G, Sun W. Advances in the management of gastrointestinal cancers – an upcoming role of immune checkpoint blockade. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:86. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0185-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou PC, Li YH, Lin SC, et al. Hypoxia induced downregulation of DUSP 2 phosphatase drives colon cancer stemness. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4305–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pahwa M, Harris MA, MacLeod J, et al. Sedentary work and the risks of colon and rectal cancer by anatomical sub site in the Canadian census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC) Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;49:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Múnera JO, Sundaram N, Rankin SA, et al. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into colonic organoids via transient activation of BMP signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:51–64.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann SH, Hengartner MO. Programmed cell death: Alive and well in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:526–34. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed JC. Apoptosis-regulating proteins as targets for drug discovery. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:314–19. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann S. Mammalian caspases: Structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun XM, MacFarlane M, Zhuang J, et al. Distinct caspase cascades are initiated in receptor-mediated and chemical-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5053–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson CB. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. 1995;267:1456–62. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KH. Anticancer drug design based on plant-derived natural products. J Biomed Sci. 1999;6:236–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02253565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zagon IS, Donahue RN, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor-opioid growth factor receptor axis is a physiological determinant of cell proliferation in diverse human cancers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1154–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00414.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kren NP, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Modulation of the opioid growth factor receptor alters the proliferation and progression of cancer. Trends Cancer Res. 2013;9:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell AM, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Astrocyte proliferation is regulated by the OGF-OGFr axis in vitro and in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res Bull. 2013;90:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donahue RN, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Low-dose naltrexone suppresses ovarian cancer and exhibits enhanced inhibition in combination with cisplatin. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:883–95. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zagon IS, Porterfield NK, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor-opioid growth factor receptor axis inhibits proliferation of triple negative breast cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:589–99. doi: 10.1177/1535370213489492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge LJ, Kastin AJA. A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the mu-opiate receptor. Nature. 1997;386:499–502. doi: 10.1038/386499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janecka A, Staniszewska R, Fichna J. Endomorphin analogs. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:3201–8. doi: 10.2174/092986707782793880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentilucci L. New trends in the development of opioid peptide analogues as advanced remedies for pain relief. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:19–38. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentilucci L, Squassabia F, Artali R. Re-discussion of the importance of ionic interactions in stabilizing ligand-opioid receptor complex and in activating signal transduction. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:185–96. doi: 10.2174/138945007779315704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piekielna J, Kluczyk A, Gentilucci L, et al. Ring size in cyclic endomorphin-2 analogs modulates receptor binding affinity and selectivity. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:6039–46. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00565e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li T, Shiotani K, Miyazaki A, et al. Bifunctional [2′,6′-dimethyl-L-tyrosine1] endomorphin-2 analogues substituted at position 3 with alkylated phenylalanine derivatives yield potent mixed mu-agonist/delta-antagonist and dual mu-agonist/delta-agonist opioid ligands. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2753–66. doi: 10.1021/jm061238m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ling YH, Liebes L, Zou Y, Perez-Soler R. Reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the apoptotic response to Bortezomib, a novel proteasome inhibitor, in human H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biol Chem. 2003;278:33714–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan L, O’Callaghan YC, O’Brien NM. The role of the mitochondria in apoptosis induced by 7β-hydroxycholesterol and cholesterol-5β, 6β-epoxide. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:519–25. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang L, Zhang Y. Mitochondria are the primary target in isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1250–59. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doi S, Soda H, Oka M, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor FR901228 induces caspase-dependent apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway in small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;3:1397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogbourne SM, Suhrbier A, Jones B, et al. Antitumor activity of 3-ingenylangelate: plasma membrane and mitochondrial disruption and necrotic cell death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2833–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotem R, Heyfets A, Fingrut O, et al. Jasmonates: Novel anticancer agents acting directly and selectively on human cancer cell mitochondria. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1984–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu CC, Chan ML, Chen WY, et al. Pristimerin induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells via direct effects on mitochondria. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1277–85. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayward RL, Macpherson JS, Cummings J, et al. Enhanced oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis following antisense Bcl-xl down-regulation is p53 and Bax dependent: Genetic evidence for specificity of the antisense effect. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinicrope FA, Penington RC. Sulindacsulfide-induced apoptosis is enhanced by a small-molecule Bcl-2 inhibitor and by TRAIL in human colon cancer cells over-expressing Bcl-2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1475–83. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamanaka K, Rocchi P, Miyake H, et al. A novel antisense oligonucleotide inhibiting several antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members induces apoptosis and enhances chemosensitivity in androgen-independent human prostate cancer PC3 cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1689–98. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Childs AC, Phaneuf SL, Dirks AJ, et al. Doxorubicin treatment in vivo causes cytochrome C release and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, as well as increased mitochondrial efficiency, superoxide dismutase activity, and Bcl-2/Bax ratio. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4592–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katiyar SK, Roy AM, Baliga MS. Silymarin induces apoptosis primarily through a p53-dependent pathway involving Bcl-2/Bax, cytochrome c release, and caspase activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:207–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batra S, Reynolds CP, Maurer BJ. Fenretinide cytotoxicity for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor cell lines is decreased by hypoxia and synergistically enhanced by ceramide modulators. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5415–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang CC, Liu TY, Cheng CH, Jan TR. Involvement of the mitochondrion-dependent pathway and oxidative stress in the apoptosis of murine splenocytes induced by areca nut extract. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:840–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao D, Powolny AA, Antosiewicz J, et al. Cellular responses to cancer chemopreventive agent D,L-sulforaphane in human prostate cancer cells are initiated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1729–38. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9883-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Kong X, Kang J, et al. Oxidative stress induces parallel autophagy and mitochondria dysfunction in human glioma U251 cells. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110:376–88. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franke TF, Hornik CP, Segev L, et al. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: Size matters. Oncogene. 2003;22:8983–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panka DJ, Mano T, Suhara T, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt activity regulates c-FLIP expression in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6893–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]