Abstract

Objective

To examine the psychological effects on clinicians of working to manage novel viral outbreaks, and successful measures to manage stress and psychological distress.

Design

Rapid review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed/Medline, PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Google Scholar, searched up to late March 2020.

Eligibility criteria for study selection

Any study that described the psychological reactions of healthcare staff working with patients in an outbreak of any emerging virus in any clinical setting, irrespective of any comparison with other clinicians or the general population.

Results

59 papers met the inclusion criteria: 37 were of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), eight of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19), seven of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), three each of Ebola virus disease and influenza A virus subtype H1N1, and one of influenza A virus subtype H7N9. Of the 38 studies that compared psychological outcomes of healthcare workers in direct contact with affected patients, 25 contained data that could be combined in a pairwise meta-analysis comparing healthcare workers at high and low risk of exposure. Compared with lower risk controls, staff in contact with affected patients had greater levels of both acute or post-traumatic stress (odds ratio 1.71, 95% confidence interval 1.28 to 2.29) and psychological distress (1.74, 1.50 to 2.03), with similar results for continuous outcomes. These findings were the same as in the other studies not included in the meta-analysis. Risk factors for psychological distress included being younger, being more junior, being the parents of dependent children, or having an infected family member. Longer quarantine, lack of practical support, and stigma also contributed. Clear communication, access to adequate personal protection, adequate rest, and both practical and psychological support were associated with reduced morbidity.

Conclusions

Effective interventions are available to help mitigate the psychological distress experienced by staff caring for patients in an emerging disease outbreak. These interventions were similar despite the wide range of settings and types of outbreaks covered in this review, and thus could be applicable to the current covid-19 outbreak.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, viral diseases represent a serious threat to public health, with novel viruses continuing to emerge. Several viral epidemics have occurred in the past 20 years, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, influenza caused by the virus subtype H1N1 in 2009, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, and Ebola virus disease in 2014.1 2 3 In 2019, a novel virus belonging to the coronavirus (CoV) family, SARS-CoV-2, emerged in Wuhan, the largest metropolitan area in China’s Hubei province.4 5 This was first reported to the WHO Country Office in China at the end of that year and is now known as covid-19. Although this is a new strain, related coronaviruses can cause illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as SARS and MERS.1

As an example, SARS-CoV in 2009 caused a large scale epidemic of SARS that began in China before spreading to 24 countries, with about 8000 people infected and 800 deaths. Aside from mainland China, the disease was concentrated in four areas: Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Toronto, Canada.1 SARS-CoV was eventually contained by means of syndromic surveillance, prompt isolation of patients, strict enforcement of quarantine of all contacts, and, in some areas, community level quarantine. MERS-CoV emerged in Saudi Arabia and has infected about 2500 people and resulted in 800 deaths.1 It is still responsible for sporadic cases.

There have also been recent outbreaks of new influenza strains such as H1N1 (swine flu) that emerged in North America in 2009, and a novel virus of avian origin (H7N9) four years later in China.2 6 The largest outbreak of Ebola virus disease was in West Africa from 2013 to 2016, but the virus was first discovered in 1976 after an outbreak in Central Africa. Ebola virus is transmitted by bodily fluids.3

Each of these past outbreaks raised similar problems for both health services and staff in terms of the psychological impact of increased workload, the need for personal protection, and fears of possible infection of themselves and their families. This information might now provide guidance for healthcare workers in the latest coronavirus pandemic. We therefore undertook a rapid review of the psychological effects on clinicians working in past outbreaks and measures that successfully managed these effects. Rapid reviews target high quality and authoritative resources for time critical decision making or clinically urgent questions.7 Yet like a systematic review, rapid reviews identify the key concepts, theories, and resources in a specialty and survey the major research studies.7

Methods

Search strategy

We followed guidelines for the conduct of rapid reviews.7 One of the authors, who was a research librarian (CD), searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO from inception to late March 2020. No language restrictions were applied. The search terms are described in the supplementary file. Three of the authors (LM, IH, and NW), working in pairs, independently screened records, abstracts, and full text articles. Two authors extracted data (LM and NW). When consensus was lacking, a third reviewer was consulted (SK). The reference lists of selected retrieved papers were screened to identify additional studies that met inclusion criteria. To locate the most recent papers on covid-19, we also searched medRxiv, an online archive and distribution server, for complete but unpublished manuscripts (preprints) in the medical and health sciences.

Inclusion criteria

We included any study that described the psychological reactions of healthcare staff working with patients in an outbreak of any emerging virus in any clinical setting, irrespective of any comparison with other clinicians or the general population. These outbreaks were SARS, MERS, H1N1, H7N9, Ebola virus disease, and covid-19. Study designs eligible for inclusion were case reports, series, and qualitative, cross sectional, case-control, and cohort studies. We excluded studies that assessed the psychological responses of patients or healthcare workers who had contracted a viral illness.

All studies identified for inclusion were qualitative, cohort, or cross sectional studies. We assessed quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for non-randomised studies.8 This covered the three broad areas of selection of the study groups in terms of case definition, representativeness, and source of controls; comparability of the groups, such as the use of matching or multivariate techniques; and measurement of exposure and outcomes in a valid and reliable way. The version for cross sectional studies has eight items and the one for longitudinal designs has 11, with a score of 7 and above an indicator of study quality. The qualitative version has 10 items.9

As recommended in rapid review guidelines,7 we also assessed the level of evidence for the quantitative studies using a modified framework from the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group.10 Platinum and gold ratings are reserved for evidence from randomised controlled trials. Silver refers to non-randomised studies with controls, whereas bronze is for all other designs.10

When data were available for three or more studies, we used RevMan and Win-Pepi programs to combine the data in a meta-analysis.11 As we could not definitely exclude variation between studies, we used a random effects model for all the analyses and an I2 statistic estimate of 50% or more as an indicator of possible heterogeneity. When there were 10 or more studies for any outcome, we tested for publication bias with funnel plot asymmetry; low P values suggesting publication bias. Finally, we undertook a sensitivity analysis of the effect of restricting analyses to studies with a Joanna Briggs Institute score of 7 or higher, or of excluding preprint studies that had not undergone peer review.

Patient and public involvement

As this was a rapid review, patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, or reporting of this research.

Results

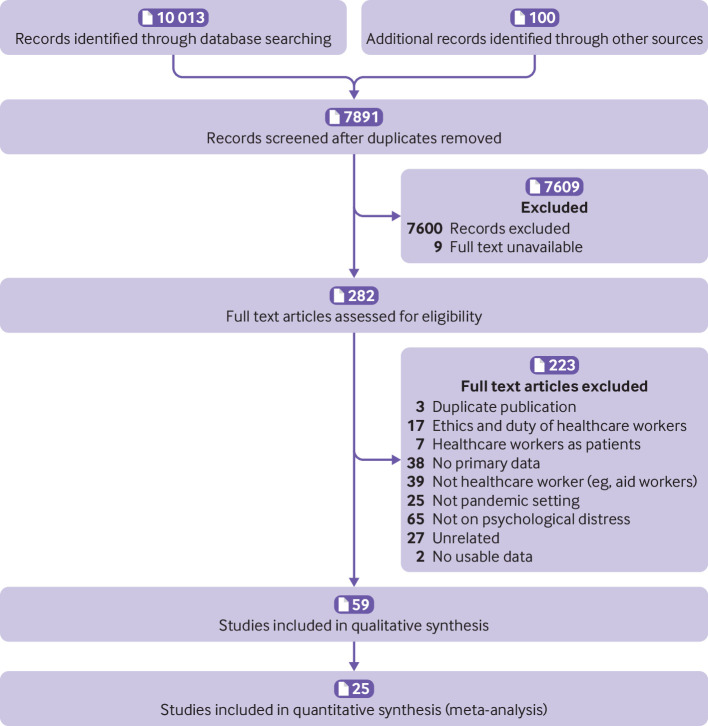

Overall, 10 013 citations of interest were found in the initial electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed/Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO, as well as a further 100 from other sources, including 91 from medRxiv. Of these, 282 full text papers were potentially relevant and assessed for eligibility (fig 1). The full text of nine studies could not be found.

Fig 1.

Flow of studies through review

Fifty nine papers met the inclusion criteria. Of the included studies, seven were of MERs,12 13 14 15 16 17 18 three of Ebola virus disease,19 20 21 eight of covid-19,22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 three of H1N1,30 31 32 one of H7N96 30 31 32 (supplementary table 1), and the remaining 37 of SARS.33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 Thirteen came from mainland China, 10 each from Taiwan and Canada, nine from Hong Kong, five each from Singapore and South Korea, two from Saudi Arabia (MERS), and one each from Greece (H1N1), Mexico (H1N1), Japan (H1N1), the Netherlands (Ebola virus disease), Germany (Ebola virus disease), and Liberia (Ebola virus disease) (supplementary table 1). Three papers were in Mandarin,24 61 62 one in Spanish,32 and the remainder in English. Forty seven were cross sectional studies, eight longitudinal designs, three qualitative papers, and the last a narrative report.22 Forty five studies were of psychosocial outcomes during a viral outbreak, and the remaining 14 presented findings for up to three years of follow-up (supplementary table 1).

Study quality was fair, with most studies (n=45) scoring 7 or higher (supplementary table 1). The most common problem affecting study quality was failure to identify and deal with confounding factors in the cross sectional (table 1) and cohort (table 2) designs. In the case of the three qualitative papers, study quality was affected by failure to locate the researcher culturally or theoretically,8 or failure to acknowledge the influence of the researcher on the research. Similarly, 38 studies were rated silver for quantitative evidence and 17 as bronze. It was not possible to assign Joanna Briggs Institute scores to one study as it was a brief narrative description of the experience of dealing with covid-19.22

Table 1.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scores for cross sectional studies

| Study | JBI score | Participants and setting described in detail, including similarity of controls | Criteria for inclusion clearly defined and exposures similarly measured | Exposure measured in valid and reliable way | Objective, standard criteria used for measurement of condition | Confounding factors identified | Strategies to deal with confounding factors stated | Outcomes measured in valid and reliable way | Appropriate statistical analysis used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria-Corrales 2011 | 7 | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bai 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bukhari 2016 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Chan 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chan 2005 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Cheng-Sheng Chen 2005 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Chua 2004 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Fiksenbaum 2006 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Goulia 2010 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Grace 2005 | 5 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + |

| Hawryluck 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ho 2005 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Huang 2020 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Khalid 2016 | 4 | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Kim 2016 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Koh 2005 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Lai 2020 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lee 2005 | 4 | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Lehmann 2016 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Li 2015 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lu 2006 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Maunder 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Maunder 2006 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Nickell 2004 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Oh 2017 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Park 2018 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Phua 2005 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tam 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tang 2017 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Verma 2004 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Wu 2009 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Yu 2003 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Xuehua 2003 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Lin 2007 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Marjanovic 2007 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Matsuishi 2012 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Poon 2005 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Sim 2004 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sin 2004 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Styra 2008 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Wong 2005 | 6 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Wong 2004 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Xing 2020; preprint | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Liu 2020; preprint | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Huang 2020; preprint | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Zhou 2020; preprint | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Dai 2020; preprint | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

Table 2.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scores for longitudinal studies

| Study | JBI score | Participants and setting described in detail, including similarity of controls | Criteria for inclusion in sample clearly defined and exposures similarly measured | Exposure measured in valid and reliable way | Objective, standard criteria used for measurement of condition | Confounding factors identified | Strategies to deal with confounding factors stated | Outcomes measured in valid and reliable way | Appropriate statistical analysis used? | Sufficient follow-up time | Reasons for loss of follow-up | Strategies to deal with incomplete follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen 2006 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Chen 2007 | 7 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Chong 2004 | 9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Lee 2018 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Lung 2009 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| McAlonan 2007 | 9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Su 2007 | 9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Lancee 2008 | 7 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - |

Psychosocial outcomes

A wide range of tools were used. The most common standardised instrument to measure symptoms of stress was the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R). For psychological distress, the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies-depression scale (CES-D) and the general health questionnaire (GHQ), or its Chinese version (CHQ), were used most often (supplementary table 1). Other common tools included the Maslach burnout inventory and the medical outcome study short-form 36 Survey (MOS SF-36) (supplementary table 1).

Thirty eight studies compared psychological outcomes between healthcare workers who were in direct contact with affected patients and those who had little or no contact.6 14 16 17 18 21 23 25 26 27 28 31 32 33 34 36 37 38 39 41 42 44 48 49 53 54 55 56 58 59 60 62 64 66 67 68 69 70 In some cases, this was with clinical staff and in others with administrative staff. In one study the comparison was with the community.

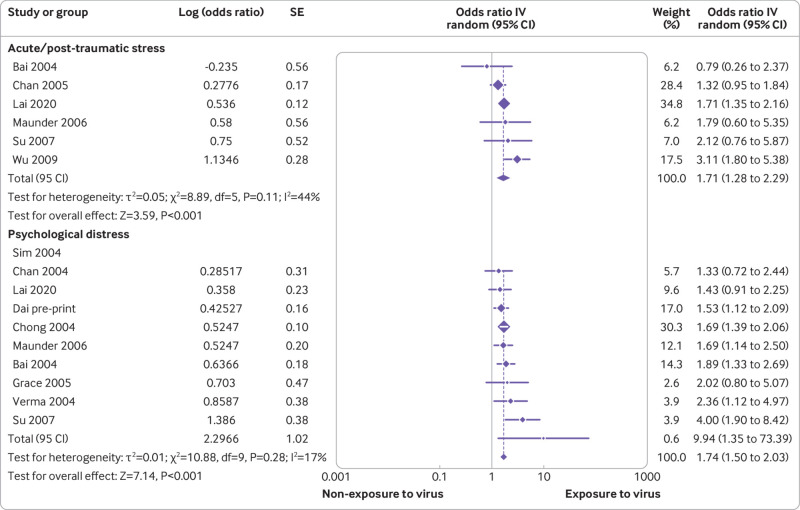

Of these 38 studies, 25 contained data that could be combined in a pairwise meta-analysis. Five were of covid-19, three of MERS, one of Ebola virus disease, and the remainder of SARS (figs 2 and 3). Twenty three of the 25 studies scored 7 or higher for study quality on the Joanna Briggs Institute tool, with levels of evidence rated as silver. Staff in contact with patients had higher levels of both acute or post-traumatic stress and psychological distress (figs 2 and 3). In all comparisons of dichotomous data, the I2 statistic was less than 50% (fig 2), but comparisons of continuous data did show evidence of heterogeneity (fig 3). Sensitivity analyses excluding lower quality studies or studies that were published as preprints did not affect the overall results.

Fig 2.

Comparison of dichotomous outcomes between low and high risk exposure groups. IV=inverse variance

Fig 3.

Comparison of continuous scores between low and high risk exposure groups. SMD=standardised mean difference; IV=inverse variance

In two of the four outcomes it was possible to test for publication bias with funnel plots: psychological distress as a dichotomous variable and acute or post-traumatic stress as a continuous variable. Egger’s regression asymmetry test was non-significant for psychological distress (1.18, 90% confidence interval 0.33 to 2.03; P=0.09) indicating the possible absence of publication bias. Similar results were found for Egger’s regression asymmetry test in the case of acute or post-traumatic stress (2.07, 90% confidence interval 0.23 to 3.91; P=0.15)

Higher psychosocial morbidity was also reported in the other studies that were not included in the meta-analysis, with contact being associated with greater burnout, acute stress, and psychological stress (supplementary table 1). There were only three exceptions. One was a study of staff in a regional hospital in Singapore that was not the designated hospital for SARS, with the result that patients were rapidly transferred elsewhere thereby reducing contact.34 In a study from Hong Kong, both healthcare workers and community controls had high scores during the SARS outbreak in 2003 that were significantly higher than population norms.37 A similar pattern was found in the third study where staff, irrespective of contact with patients affected by SARS, had higher psychological morbidity than the general population.33

Studies without controls also showed high rates of psychological distress and disorders in those who cared for patients with SARS or MERS (supplementary table 1). Increased levels of stress and psychological distress were evident both during and after the outbreak (supplementary table 1), persisting up to three years later in one study.59

Boxes 1 to 3 present our findings on predisposing (box 1) and protective factors (box 2) for psychological outcomes, as well as interventions to mitigate these outcomes (box 3).

Box 1. Factors that increase risk of adverse psychological outcomes.

Individual factors

Clinical

Increased contact with affected patients6 14 16 17 18 23 25 26 31 33 36 38 39 41 44 47 48 49 53 55 56 58 59 60 62 63 64 66 67 70

Precautionary measures creating perceived impediment to doing job50 64

Training and experience

Lower levels of education46

Part time employee50

Personal

Personal lifestyle impacted by epidemic/pandemic50

Psychological

History of psychological distress, mental health disorders, or substance misuse29 42 45 46 48 53 54 66 69

Service factors

Societal factors

All studies cited in box are high quality apart from references 13, 14, 26, 30, 39-41, 54, and 52.

*Two studies reported a higher risk for doctors34 46 and 10 reported a higher risk for nurses.6 23 30 41 50 55 57 64 65 66

Box 2. Factors that decrease risk of adverse psychological outcomes.

Individual factors

Service factors

Societal factors

A general drop in disease transmission13

All studies cited in box are high quality apart from references 13, 40, 41, 45, 49, 52, and 54.

Box 3. Recommendations to deal with psychological problems in healthcare workers in novel outbreaks.

Individual factors

Service factors

Communication and training

Training and education around infectious diseases16 18 25 26 35 37 39 42 43

Infection control

Clear direction and enforcement of infection control procedures13 23 34 35 40 41 43 67

Screening stations to direct patients to relevant infection treatment clinics56

Sufficient supplies of adequate protective equipment12 13 17 23 25 35 41 43 56 67

Redesigning nursing care procedures that pose high risks for spread of infections34 67

Improving safety such as a better ventilation system or constructing or negative pressure rooms to isolate patients34 67

Psychological

Recognition of staff efforts13

Training to deal with identification of and responses to psychological problems22 28

Access to psychological interventions16 21 22 23 26 29 33 35 38 43 55 60 62 65

Workload

Avoidance of compulsory assignment to caring for patients with coronavirus35 55

Rearranging hospital infrastructure, such as redeployment of wards and human resources34 67

Availability of hospital security to help deal with uncooperative patients22

Personal support

Alternative accommodation for staff who are concerned about infecting their families22 33 67

Video facilities for staff to keep in contact with families and alleviate their concerns22

Societal factors

All studies cited in box are high quality apart from references 13, 26, 30, 39-41, 45, and 52

Predisposing factors

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, staff who were women,6 16 23 26 29 36 younger,32 50 55 59 69 or parents of dependent children41 66 were more vulnerable to psychological distress. Linked to this was social isolation,34 66 70 particularly if staff were exposed to prolonged quarantine,14 33 38 59 63 72 and the fear of infecting their family or having an infected family member.25 29 59 Staff with self-reported pre-existing psychological29 42 45 46 48 53 54 66 69 or physical29 40 55 67 ill health were also more at risk, as were those with a higher fear of SARS.58

Aside from close contact with affected patients, work related risk factors included being less experienced,6 18 36 42 in part time employment,50 or in increased contact with affected patients.6 14 16 17 18 23 25 26 31 33 36 38 39 41 44 47 48 49 53 55 56 58 59 60 62 63 64 66 67 70 Within the clinical group, nurses were generally more at risk than doctors,6 23 30 41 50 55 57 64 65 66 apart from two studies that reported the opposite34 46 (box 3). Staff also expressed frustration about the effect of precautionary measures on their ability to do their jobs.50 64 Practical support from the employer, however, was also key; such as the provision of appropriate work wear. 3 17 29 41 43 52 55 58 66 67 For example, one study reported that staff in one hospital were not allowed to wear theatre “greens” while on duty because of fears about theft and were told to wear their own clothes.66 Many resorted to changing in their garage on returning home out of fear of infecting their family.

Wider service and societal factors included inadequate staff training,48 organisational support,12 38 47 48 55 66 and compensation,13 43 as well as societal stigma against healthcare workers.15 40 41 50 51 66 Findings were generally similar in both low and high quality studies.

Protective factors

Staff who were older or who had greater clinical experience, experienced less stress. The exceptions were in two studies of staff caring for patients with covid-19, when older age was a risk factor for psychological symptoms.28 59 Frequent short breaks from clinical duties,40 adequate time off work,32 33 43 60 family support,17 35 52 a perception of being adequately trained,37 43 48 a supportive work environment,12 17 19 34 39 43 52 67 clear communication with staff,31 34 52 55 and faith in precautionary measures35 40 50 52 were also protective. Having access to psychological interventions35 43 55 60 65 and the development of staff support protocols34 71 were noted to be protective. Although nurses might be more vulnerable to psychological distress than other healthcare workers, they were more likely to adhere to infection control procedures.64 Many studies highlighted access to adequate personal protection equipment (PPE).13 17 29 41 43 52 55 58 66 67 Lastly, seeing infected colleagues getting better,13 as well as a general drop in disease transmission,13 improved psychological outcomes. Findings were generally similar in both low and high quality studies.

Helpful strategies

Employers can implement several practical steps to minimise the burden on clinical staff, and recommendations were similar regardless of study quality. The most consistent findings were the need for clear communication,12 30 33 34 38 56 66 providing training and education around infectious diseases,16 18 25 26 35 37 39 42 43 enforcement of infection control procedures,13 23 34 35 40 41 43 67 adequate supplies of protective equipment,12 13 17 23 25 35 41 43 56 67 and access to psychological interventions.16 21 22 23 26 29 33 35 38 43 55 60 62 65 These should be supplemented by simple changes to practice, such as screening stations to direct patients to relevant infection treatment clinics,56 redesigning procedures that pose high risks for spread of infections,34 67 and reducing the density of patients on wards.34 67

Supervisors need to consider staff based factors when allocating duties, particularly if staff are redeployed to meet increasing clinical demand. When possible, such redeployment should be voluntary.35 55 In addition, staff caring for affected patients should be rostered to appropriate work shifts with regular breaks.12 40 43 During breaks, staff should be provided with food and other daily living supplies,13 22 43 with the possibility of video contact with families to alleviate concerns.22 Some staff might require alternative accommodation to reduce the risks of infecting their families.22 33 67 On a societal level, stigma and discrimination against healthcare workers must be tackled.15 40 41 50 51 66

Two studies, one of SARS and one of MERS, asked staff to rate the utility of interventions on a 4 point scale (0=not effective, 1=mildly effective, 2=moderately effective, 3=very effective).13 43 Support from colleagues, sufficient time off, adequate protective equipment, stringent infection control, and patient improvement were common to both settings. A study of staff caring for patients with MERS found that adequate hospital resources were associated with reduced burnout, as was support from the family, and this was reflected in a study of SARS, where organisational support, adequate resources, and time in quarantine predicted psychological outcomes.47

One (uncontrolled) study evaluated the effect of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan’s largest hospital for the treatment of the disease.35 This incorporated many of the mentioned recommendations and consisted of intensive in-service training covering basic knowledge of protection and patient care, the removal and disinfection of P100 masks, the procedures for entering isolation wards, and hospital control of SARS infection. Shifts were limited to eight hours to avoid fatigue and the hospital had comprehensive PPE, including scrub suits, isolating dresses, surgical caps, sterilised gloves, foot wraps, N95 masks, surgical masks, P100 masks, and safety glasses. Both patients and staff had access to a multidisciplinary mental health team. Ratings of depression and anxiety showed statistically significant improvements in the two to four weeks after introduction of the interventions.

Discussion

This review has highlighted the importance of considering the mental health of healthcare workers who are caring for patients during a viral outbreak. Although psychological distress is to be expected in situations where staff are under pressure to look after a large number of potentially infectious patients, employers can help to mitigate this by immediate implementation of several effective interventions. And despite the wide range of settings and types of viral outbreaks, these interventions are similar and thus highly applicable to the current covid-19 outbreak. Broadly the interventions concern communication, access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), adequate rest, and both practical and psychological support.

Policy implications

The World Health Organization has recently released resources that give specific guidance on mental health and psychosocial considerations during the covid-19 outbreak, including psychological first aid (PFA) for frontline workers.72 73 Psychological first aid includes the assessment of needs and concerns; practical care and support; dealing with basic needs (for example, food and water, information); empathic listening; access to information, services, and social supports; and protection from further harm.74 By contrast, psychological debriefing focusing on traumatic experiences is not usually helpful and could interfere with the natural recovery process.75

Care of both the patients with covid-19 and their healthcare workers extends beyond their immediate needs to also tackling the discrimination and stigma that was identified in many of the studies. WHO has produced guidance for opinion makers and the media on how to describe the outbreak. For example, the illness should be described by its official name (covid-19), which was deliberately chosen to avoid stigmatisation, rather than by reference to specific locations or ethnicity.72 WHO also recommends highlighting the effectiveness of preventive measures rather than focusing on individual behaviour and presumed responsibility for having or spreading covid-19. In addition, featuring people who have recovered, or healthcare workers who supported them through recovery, can emphasise that most people recover from covid-19.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths of this study are consideration of a range of emerging viral illnesses worldwide, including early experience with covid-19, and a search that included low and middle income countries that are at equivalent potential risk and where solutions from North America or East Asia might be less applicable. We combined the relevant data in a meta-analysis, and collected data on the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of psychological morbidity in healthcare workers. Our findings on the psychological effects on clinicians are the same as those in an earlier systematic review without a meta-analysis, which was restricted to the SARS outbreak in Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and mainland China.76

Our study has several limitations. Despite our broad search, we only identified one study from a low to middle income country.20 In addition, we were unable to locate the full text of nine studies that might have been relevant. Only three studies undertook evaluations of interventions. One found that a hospital based SARS prevention programme in Taiwan led to improved scores on anxiety, depression, and sleep quality scales,35 whereas two used the same self-report scale to assess participants’ perceived usefulness of measures to reduce stress.13 43 This finding was reflected in another systematic review, which only found three studies that evaluated interventions to improve the resilience of clinicians working in a viral outbreak, one of which was in preparation for a potential influenza pandemic.77 The third study in that review was the before and after evaluation of the effect of a SARS prevention programme on anxiety and depression during the outbreak in Taiwan that was included in our review.35

Study quality was only fair, with 45 out of the 59 studies scoring 7 or higher on the Joanna Briggs Institute tool. In addition, we were only able to meta-analyse data from 25 of the studies, although it is important to note that all but two of these were good quality studies, and all were rated silver on quality of evidence. This is the highest possible rating for a non-randomised study.10 Results for the two continuous outcomes showed high heterogeneity, which is why we have emphasised the dichotomous results where the I2 score was low. Finally, we were only able to test for publication bias in the two outcomes that had 10 or more studies.

Conclusions

Papers of previous emerging virus outbreaks offer important insights that might be relevant for the present covid-19 outbreak, including strategies that could be easily employed to minimise the psychological distress of healthcare workers. Further research is required into the effectiveness of these interventions, particularly during the covid-19 pandemic.

What is already known on this topic

In the past 20 years, viral epidemics such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (2003), H1N1 influenza (2009), Middle East respiratory syndrome (2012), and Ebola virus disease (2014), and the current covid-19 pandemic have raised similar problems for health services and staff about the psychological impact of increased workload, need for personal protection, and fears of infection for themselves and their families

Risk and protective factors for healthcare worker’s psychological wellbeing need to be collated, and recommendations outlined for improving the psychological wellbeing of healthcare workers during the current covid-19 pandemic

What this study adds

Compared with lower risk controls, staff in contact with affected patients had greater levels of both acute or post-traumatic stress and psychological distress

Risk factors for psychological distress included being younger, more junior, parents of dependent children, and in quarantine, having an infected family member, lack of practical support, and stigma

Clear communication, access to adequate personal protection, adequate rest, and both practical and psychological support were associated with reduced morbidity

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: search terms

Supplementary information: table showing included studies

Contributors: SK conceptualised the project with input from DS. CD devised the search with support from DS. LM, IH, and NW conducted the search. All authors were involved with data extraction and validation. SK conducted the data analysis with support from DS. SK and DS interpreted the data with support from NW and LM. SK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing and approving the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. SK and DS act as guarantors.

Funding: No funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The authors intend to disseminate this research through social media, press releases to mainstream media, media interviews, and direct dissemination to hospital and health service directors in relevant jurisdictions.

The lead authors (SK and DS) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. Ashour HM, Elkhatib WF, Rahman MM, Elshabrawy HA. Insights into the Recent 2019 Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Light of Past Human Coronavirus Outbreaks. Pathogens 2020;9:186. 10.3390/pathogens9030186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, et al. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2605-15. 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feldmann H, Jones S, Klenk H-D, Schnittler HJ. Ebola virus: from discovery to vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:677-85. 10.1038/nri1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, et al. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lake MA. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research [published Online First: 2020/03/07]. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:124-7. 10.7861/clinmed.2019-coron. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tang L, Pan L, Yuan L, Zha L. Prevalence and related factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among medical staff members exposed to H7N9 patients. Int J Nurs Sci 2016;4:63-7. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012;1:10. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7. Systematic reviews of aetiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017: 5. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:179-87. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maxwell L, Santesso N, Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Judd M, Buchbinder R. Method guidelines for Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group systematic reviews. J Rheumatol 2006;33:2304-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abramson JH. WINPEPI updated: computer programs for epidemiologists, and their teaching potential. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2011;8:1. 10.1186/1742-5573-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kang HS, Son YD, Chae SM, Corte C. Working experiences of nurses during the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. Int J Nurs Pract 2018;24:e12664. 10.1111/ijn.12664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare Workers Emotions, Perceived Stressors and Coping Strategies During a MERS-CoV Outbreak. Clin Med Res 2016;14:7-14. 10.3121/cmr.2016.1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A-R, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry 2018;87:123-7. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park JS, Lee EH, Park NR, Choi YH. Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital During a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2018;32:2-6. 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bukhari EE, Temsah MH, Aleyadhy AA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. J Infect Dev Ctries 2016;10:845-50. 10.3855/jidc.6925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JS, Choi JS. Factors influencing emergency nurses’ burnout during an outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Korea [Korean Soc Nurs Sci]. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2016;10:295-9. 10.1016/j.anr.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oh N, Hong N, Ryu DH, Bae SG, Kam S, Kim KY. Exploring Nursing Intention, Stress, and Professionalism in Response to Infectious Disease Emergencies: The Experience of Local Public Hospital Nurses During the 2015 MERS Outbreak in South Korea [Korean Soc Nurs Sci]. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2017;11:230-6. 10.1016/j.anr.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Belfroid E, van Steenbergen J, Timen A, Ellerbroek P, Huis A, Hulscher M. Preparedness and the importance of meeting the needs of healthcare workers: a qualitative study on Ebola. J Hosp Infect 2018;98:212-8. 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li L, Wan C, Ding R, et al. Mental distress among Liberian medical staff working at the China Ebola Treatment Unit: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:156. 10.1186/s12955-015-0341-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lehmann M, Bruenahl CA, Addo MM, et al. Acute Ebola virus disease patient treatment and health-related quality of life in health care professionals: A controlled study. J Psychosom Res 2016;83:69-74. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e15-6. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019 [published Online First: 2020/03/24]. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang J, Han M, Luo T, et al. [Mental health survey of 230 medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2020;38:E001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai Y, Hu G, Xiong H, et al. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. medRxiv 2020.03.03.20030874 [Preprint]. 2020.

- 26.Huang L, Xu F, Liu H. Emotional responses and coping strategies of nurses and nursing college students during COVID-19 outbreak. medRxiv 2020.03.05.20031898 [Preprint]. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Liu C, Yang Y, Zhang X, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors for anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional survey. medRxiv 2020 2020.03.05.20032003 [Preprint]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Xing J, Sun N, Xu J, et al. Study of the mental health status of medical personnel dealing with new coronavirus pneumonia. medRxiv 2020 2020.03.04.20030973 [Preprint]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Zhu Z, Xu S, Wang H, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: Immediate Psychological Impact on 5062 Health Workers. medRxiv 2020 2020.02.20.20025338 [Preprint].

- 30. Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, Mantis D, Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:322. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;66:353-60. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Austria-Corrales F, Cruz-Valdés B, Herrera-Kiengelher L, Vázquez-García JC, Salas-Hernández J. [Burnout syndrome among medical residents during the influenza A H1N1 sanitary contigency in Mexico.] Gac Med Mex 2011;147:97-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bai Y, Lin C-C, Lin C-Y, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:1055-7. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan AOM, Huak CY. Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med (Lond) 2004;54:190-6. 10.1093/occmed/kqh027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen R, Chou K-R, Huang Y-J, Wang TS, Liu SY, Ho LY. Effects of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan on nursing staff’s anxiety, depression and sleep quality: a longitudinal survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:215-25. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chong M-Y, Wang W-C, Hsieh W-C, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:127-33. 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:391-3. 10.1177/070674370404900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fiksenbaum L, Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, et al. Emotional exhaustion and state anger in nurses who worked during the SARS outbreak: The role of perceived threat and organizational support. Can J Commun Ment Health 2007;25:89-103 10.7870/cjcmh-2006-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grace SL, Hershenfield K, Robertson E, Stewart DE. The occupational and psychosocial impact of SARS on academic physicians in three affected hospitals. Psychosomatics 2005;46:385-91. 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ho SMY, Kwong-Lo RSY, Mak CWY, Wong JS. Fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) among health care workers. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:344-9. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, et al. Risk perception and impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med Care 2005;43:676-82. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lancee WJ, Maunder RG, Goldbloom DS, Coauthors for the Impact of SARS Study Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:91-5. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee S-H, Juang Y-Y, Su Y-J, Lee HL, Lin YH, Chao CC. Facing SARS: psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005;27:352-8. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin CY, Peng YC, Wu YH, Chang J, Chan CH, Yang DY. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg Med J 2007;24:12-7. 10.1136/emj.2006.035089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lu Y-C, Shu B-C, Chang Y-Y, Lung FW. The mental health of hospital workers dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75:370-5. 10.1159/000095443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lung F-W, Lu Y-C, Chang Y-Y, Shu BC. Mental symptoms in different health professionals during the SARS attack: A follow-up study. Psychiatr Q 2009;80:107-16. 10.1007/s11126-009-9095-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Coffey S. The relevance of psychosocial variables and working conditions in predicting nurses’ coping strategies during the SARS crisis: an online questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44:991-8. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:1924-32. 10.3201/eid1212.060584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:241-7. 10.1177/070674370705200406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ 2004;170:793-8. 10.1503/cmaj.1031077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robertson E, Hershenfield K, Grace SL, Stewart DE. The psychosocial effects of being quarantined following exposure to SARS: a qualitative study of Toronto health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:403-7. 10.1177/070674370404900612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sin SS, Huak CY. Psychological impact of the SARS outbreak on a Singaporean rehabilitation department. Int J Ther Rehabil 2004;11:417-24 10.12968/ijtr.2004.11.9.19589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S, Kasapinovic S, Fones C, Gold WL. Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:177-83. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Su TP, Lien TC, Yang CY, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res 2007;41:119-30. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HF. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med 2004;34:1197-204. 10.1017/S0033291704002247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Verma S, Mythily S, Chan YH, Deslypere JP, Teo EK, Chong SA. Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2004;33:743-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wong TW, Yau JK, Chan CL, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med 2005;12:13-8. 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wong WC, Lee A, Tsang KK, Wong SY. How did general practitioners protect themselves, their family, and staff during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong? J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:180-5. 10.1136/jech.2003.015594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:302-11. 10.1177/070674370905400504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen N-H, Wang P-C, Hsieh M-J, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome care on the general health status of healthcare workers in taiwan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:75-9. 10.1086/508824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liu X. Psychological Stress of Nurses working in SARS Wards. Chin Ment Health J 2003;17:526-7. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yu X, Liu J, Liu X. SCL-90 Results of Medical Staffs treating SARS. Chin Ment Health J 2003;17:524-5. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:1206-12. 10.3201/eid1007.030703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Poon E, Liu KS, Cheong DL, Lee CK, Yam LY, Tang WN. Impact of severe respiratory syndrome on anxiety levels of front-line health care workers. Hong Kong Med J 2004;10:325-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:322-8. 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Rourke S, et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom Med 2004;66:938-42. 10.1097/01.psy.0000145673.84698.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chan SS, Leung GM, Tiwari AF, et al. The impact of work-related risk on nurses during the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Fam Community Health 2005;28:274-87. 10.1097/00003727-200507000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Xuehua L, Li M, Fangiang M. Psychological stress of nurses in SARS wards. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2003;17:526-7. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1120-7. 10.4088/JCP.v65n0815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:15-23. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen C-S, Wu H-Y, Yang P, Yen CF. Psychological distress of nurses in Taiwan who worked during the outbreak of SARS. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:76-9. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization. Social Stigma associated with COVID-19. A guide to preventing and addressing social stigma. World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf (accessed 22nd April 2020).

- 73.World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak, 18 March 2020: World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/mental-health-and-psychosocial-considerations-during-the-covid-19-outbreak (accessed 22nd April 2020).

- 74.World Health Organization. Psychological first aid: guide for field workers: World Health Organization 2011. https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/guide_field_workers/en/ (accessed 22nd April 2020).

- 75. Brooks SK, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. Traumatic stress within disaster-exposed occupations: overview of the literature and suggestions for the management of traumatic stress in the workplace. Br Med Bull 2019;129:25-34. 10.1093/bmb/ldy040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. A Systematic, Thematic Review of Social and Occupational Factors Associated With Psychological Outcomes in Healthcare Employees During an Infectious Disease Outbreak. J Occup Environ Med 2018;60:248-57. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ricci-Cabello I, Meneses-Echavez J, Maria Jesús Serrano-Ripoll M, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on the mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review. medRxiv 2020 2020.04.02.20048892 [Preprint]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: search terms

Supplementary information: table showing included studies