Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

This study sought to determine if the MIND diet (a hybrid of the Mediterranean and Dash diets, with modifications based on the science of nutrition and the brain), is effective in preventing cognitive decline after stroke.

DESIGN:

We analyzed 106 participants of a community cohort study who had completed a diet assessment and two or more annual cognitive assessments and who also had a clinical history of stroke. Cognition in five cognitive domains was assessed using structured clinical evaluations that included a battery of 19 cognitive tests. MIND diet scores were computed using a valid food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Dietary components of the MIND diet included whole grains, leafy greens and other vegetables, berries, beans, nuts, lean meats, fish, poultry, and olive oil and reduced consumption of cheese, butter, fried foods, and sweets. MIND diet scores were modeled in tertiles. The influence of baseline MIND score on change in a global cognitive function measure and in the five cognitive domains was assessed using linear mixed models adjusted for age and other potential confounders.

RESULTS:

With adjustment for age, sex, education, APOE-ε4, caloric intake, smoking, and participation in cognitive and physical activities, the top vs lowest tertiles of MIND diet scores had a slower rate of global cognitive decline (β = .08; CI = 0.0074, 0.156) over an average of 5.9 years of follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS:

High adherence to the MIND diet was associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline after stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, cognitive decline, diet, nutrition, prevention

Cognitive decline is a common and devastating clinical sequela of stroke (1). Compared to the normal rate of neuron loss with aging, ischemic stroke causes 3.6 years’ worth of aging for every hour of untreated symptoms (2). With the average duration of a non-lacunar stroke lasting 10 hours, a brain may experience a magnitude of aging equivalent to several decades in just one day. Perhaps not surprisingly, stroke survivors have nearly double the risk of developing dementia compared to those who have not suffered a stroke (3). This results in a significant burden on our healthcare system, both in terms of the direct and indirect costs of stroke and dementia, as well as the emotional toll on patients and their caregivers. Therefore, lifestyle factors that may protect against these cognitive changes in stroke survivors are of great public health importance.

One lifestyle approach that may be effective for preventing post-stroke cognitive decline is diet. A number of studies have found protective associations between cognitive decline and greater adherence to the Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diets (4–7). There is limited data, however, on whether these dietary patterns might be effective in slowing the cognitive decline that can occur after stroke. In this study, we examined the associations among these healthy diet patterns and cognitive change in a community study of older adults with a clinical history of stroke.

Methods

Study Population

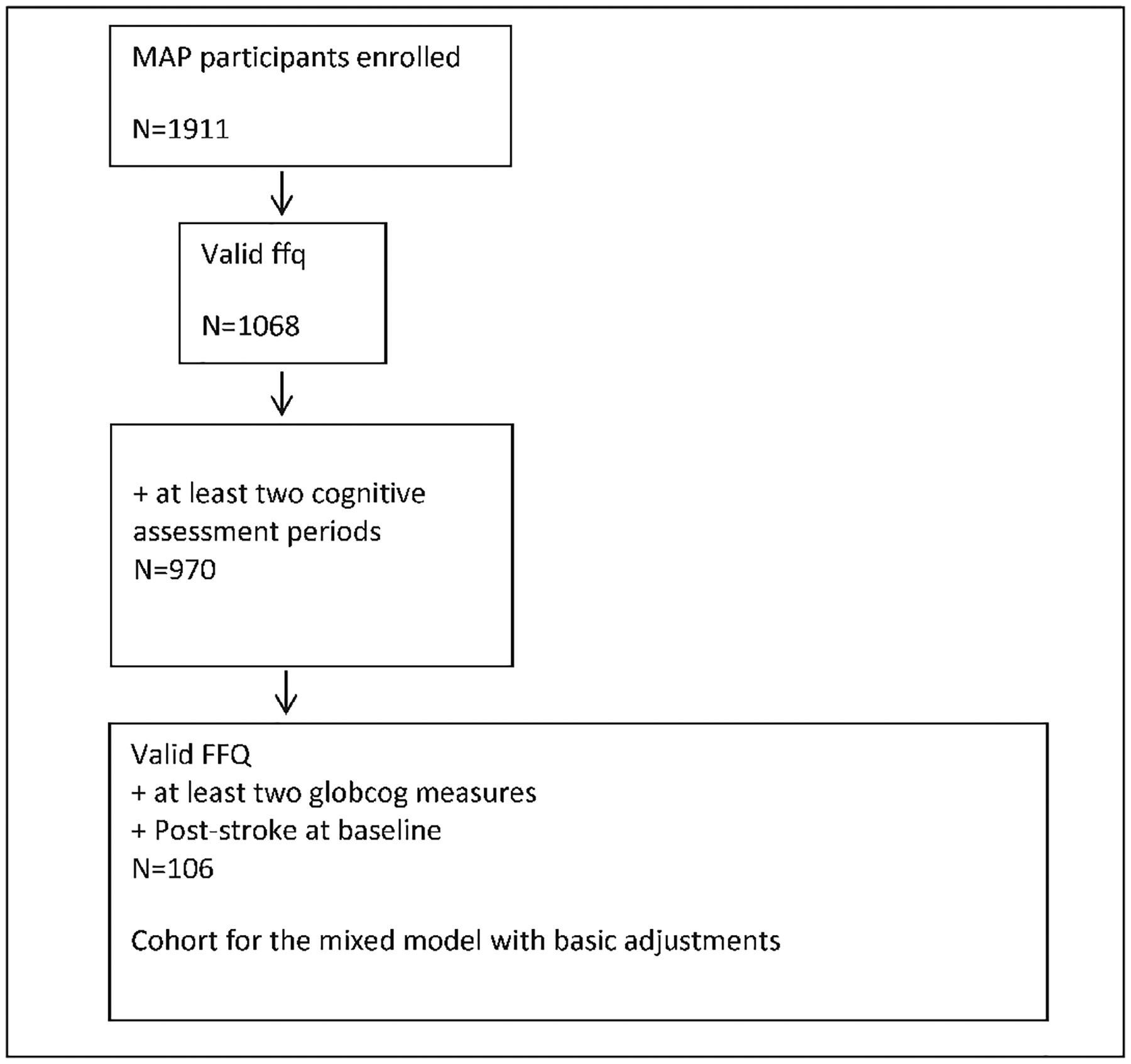

This study was conducted using data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a study of volunteers living in retirement communities and senior public housing units in the Chicago area. The ongoing open cohort study began in 1997 and includes annual clinical neurological examinations, as previously described (8). Beginning in 2004, MAP study participants began to complete comprehensive food frequency questionnaires (FFQ). Of the 1911 older persons enrolled in the MAP study, 1068 had at least one valid FFQ that served as the baseline for these analyses, of which 970 also had two or more annual cognitive assessments for the measurement of cognitive change. Among these, 106 participants had a clinical history of stroke. Average study follow-up time was 5.9 years (Figure 1). The Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Analysis cohort

Cognitive Evaluations

Cognition was assessed in 5 domains (episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual orientation, and perceptual speed), using annual structured clinical evaluations that included a battery of cognitive tests, administered by technicians trained and certified in standardized neuropsychological testing methods (9). Episodic memory was assessed with the following tests: word list, word list recall, word list recognition, East Boston immediate recall, East Boston delayed recall, logical memory 1 (immediate), and logical memory II (delayed). Semantic memory was assessed with the following tests: Boston naming (15 items), category fluency, and reading test (10 items). Working memory was assessed with the following tests: digits forward, digits backward, digit ordering. Perceptual orientation was assessed with the following tests: line orientation, progressive matrices (16 items). Finally, perceptual speed was assessed with the following tests: symbol digits modality-oral, number comparison, stroop color naming, and stroop word reading. Standardized scores were computed for each test, using the mean and standard deviation from the baseline tests, and the standardized scores were averaged over each cognitive domain and over all tests to create a global cognitive score. Out of all MAP participants, 93.4% complete annual cognitive evaluations. Of the participants in this study, 52.0% had 5 or more annual cognitive assessments, with a range of 2 to 10 years.

Diet Pattern Scoring

Diet pattern scores were based on responses to a modified Harvard semi-quantitative FFQ, that was validated for use in older Chicago community residents.(10). Typical frequency of intake of 144 food items was reported by participants over the prior 12 months. The caloric content and nutrient levels for each food item were based on age- and sex-specific portion sizes from national dietary surveys, or by a logical portion size (e.g. a slice of bread). Details of the dietary components and maximum scores for the MIND, DASH, and Mediterranean diets have been previously reported (4, 11, 12). Briefly, the MIND diet score is based on a combination of 10 healthy food groups (leafy green vegetables, other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, fish, poultry, olive oil, and wine) and 5 unhealthy food groups (red meats, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, fried food, and fast food). If olive oil was reported as the primary oil used at home, it was scored 1. Otherwise, olive oil consumption was scored 0. For the remaining components, the frequency of consumption of each food item for a given score component was summed and then given a concordance score of 0, 0.5, or 1, where 1 represented the highest concordance (4). The final MIND diet score was the sum of the 15 component scores.

Scoring for the DASH diet was determined based on consumption of 3 dietary components (total fat, saturated fat, and sodium) and 7 food groups (grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds and legumes, dairy, and meat) (12). Scores of 0, 0.5, and 1 were assigned to each food group based on the frequency of consumption. Total possible scores ranged from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest) diet concordance.

The Mediterranean diet pattern was based on the MedDiet score as described by Panagiotakos and colleagues (11) that uses serving quantities of the traditional Greek Mediterranean diet as the comparison metric. Eleven dietary components (non-refined cereals, potatoes, fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, red meat and products, poultry, full fat dairy products, the use of olive oil in cooking, and alcohol) are each scored from 0 to 5 and then summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 55 (highest concordance).

Covariates

Non-dietary variables in the analysis were obtained at the participant’s baseline clinical evaluation through a combination of clinical evaluation, self-report, medication inspection, and measurements. The process is identical to that performed in the Religious Orders Study, and was designed to reduce costs and enhance uniformity of diagnostic decisions over time and space (13). Participants self-reported their birth date and years of education. A 5 point scale was used to assess the frequency of cognitively stimulating activities (such as writing letters, visiting the library, reading, and playing games).[14] Physical activity was determined by participants self-reported minutes spent over the previous 2 weeks on 5 activities (walking for exercise, yard work, calisthenics, biking, and water exercise) (15). A modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) scale was used to evaluate depressive symptoms (16). High throughput sequencing was used to determine APOE-genotyping as previously described (17). Height and weight were measured to determine body mass index (BMI=weight in kg/height in m2) and modeled as two indicator variables, BMI ≤20 and BMI ≥30. Hypertension was defined by an average of 2 blood pressure measurements ≥ 160 mmHg systolic or ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic, or if the patient reported a clinical history of hypertension or was currently taking antihypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction history was based on the current use of cardiac glycosides (e.g. lanoxin or digoxin) or by self-reported history. Clinical history of diabetes was obtained by self-reported medical diagnosis or by current use of diabetic medications. Diagnosis of stroke was obtained through a combination of clinical evaluation and self-report to the question “has a doctor, nurse, or therapist ever told you that you have had a stroke?” (18). Medication use was based on interviewer inspection.

Statistical Analysis

The data were summarized using median and quartiles, mean and SD or number (relative frequency) as appropriate. Baseline characteristics were compared across MIND diet tertiles using Kruskal-Wallis, ANOVA, chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Linear mixed models were used to model the longitudinal global cognitive scores and the 5 cognitive domains on diet scores for the MIND, DASH, and Mediterranean diets to describe the relationships among dietary patterns and cognitive decline over time in stroke survivors. The 3 dietary patterns were examined in separate models: an age-adjusted model and a basic-adjusted model that included potential confounders previously associated with Alzheimer disease: age, sex, education, participation in cognitively stimulating activities, physical activity, smoking, and APOE-ε4. Total energy intake, which is closely related to diet, was also included as a potential confounder. The dietary scores were modeled as both continuous variables and as indicators of the top two tertiles in each of these models.

Results

Of the 106 MAP participants with a clinical history of stroke, the mean age was 82.8 years (SD=7.1) and 29 (27%) were male. The mean years of education was 14.4 (SD=2.7) Overall, 16% had APOE-ε4 alleles. Participants who had high MIND diet scores were less likely to be male, more likely to have never been smokers, and more likely to participate frequently in cognitive and physical activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Memory and Aging Project Subjects with History of Stroke

| Baseline Characteristic | Total | Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 106 | 37 | 40 | 29 |

| MIND diet score (median, q1 q3) | 7.5 (6.5, 9.0) | 6.0 (5.5, 6.5) | 7.5 (7.0, 8.0) | 9.5 (9.0, 10.5) |

| Age yr, mean (SD) | 82.8 | 82.9 | 83.3 | 82.0 |

| Males N (%) | 29 (27.4) | 12 (32.4) | 13 (32.5) | 4 (13.8) |

| Education (yr, mean) (SD) | 14.4 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 14.6 |

| APOE-ε4 (%) | 16.0 | 16.2 | 15.0 | 17.2 |

| Total Energy Intake I (mean) | 1783.9 | 1606.8 | 1914.7 | 1829.3 |

| Cognitive Activity Frequency (mean) | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| Physical Activity Weekly (hr, mean) | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 3.5 |

| Former or current smoker (%) | 44.3 | 51.4 | 45.0 | 34.5 |

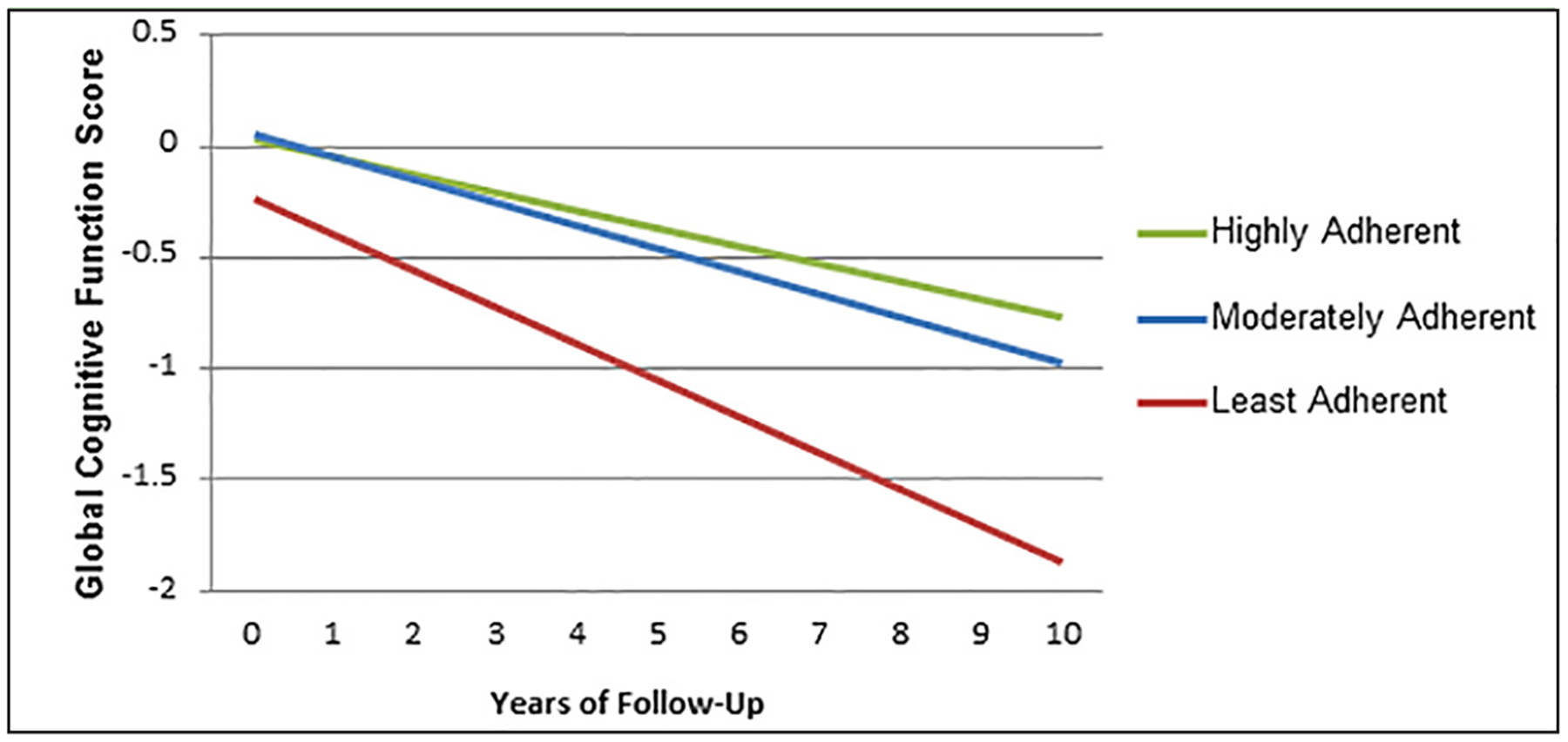

In separate models adjusted for age, sex, education, APOE-ε4, late-life cognitive activity, caloric intake, physical activity, and smoking, with diet scores modeled in tertiles, the top versus the lowest tertile of MIND diet scores were associated with a slower rate of global cognitive decline (β=0.08, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.01, 0.16), as well as with a slower decline in semantic memory (β=0.07, 95% CI: 0.00, 0.14) and perceptual speed (β=0.07, 95% CI: 0.00, 0.14), (Figure 2). Those with moderate adherence (tertile 2) to the MIND diet showed a non-significant trend toward slower rates of cognitive decline. In continuous models, the MIND diet was associated with slower rates of decline in cognitive function over time for both global cognition (p=0.034) and semantic memory (p=0.04). The DASH and Mediterranean diets were not associated with slower rates of global cognitive decline over time (p=0.26 and p=0.11, respectively) or slower decline in any of the 5 cognitive domains (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Cognitive Decline Over Time by Adherence to the MIND Diet

A graphical representation of the decrease in cognitive decline over time based on adherence to the MIND diet for 106 participants found to have had a stroke at baseline. The highest adherence (represented by the green line) versus lowest adherence (represented by the red line) to the MIND diet showed a significant decrease in cognitive decline (ß=0.08 CI= 0.00, 0.16). The decrease in cognitive decline for moderate adherence (represented by the blue line) versus lowest adherence approached significance (ß=0.06 CI=−0.01, 0.13).

Table 2.

Cognitive Function by Dietary Pattern

| Cognitive domains | Global Cognition | Episodic Memory | Semantic Memory | Visuospatial Memory | Perceptual Speed | Working Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Patterns n | 106 | 105 | 103 | 101 | 101 | 106 |

| MINDdiet | ||||||

| T1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| T2,β (Confidence interval) | 0.058 (−0.011, 0.128) | 0.025 (−0.048, 0.098) | 0.030 (−0.033, 0.093) | 0.062 (−0.001, 0.126) | 0.047 (−0.019, 0.113) | 0.023 (−0.041, 0.087) |

| T3rβ (Confidence interval) | 0.083 (0.007, 0.158) | 0.041 (−0.038, 0.121) | 0.070 (0.001, 0.138) | 0.061 (−0.008, 0.130) | 0.071 (0.000, 0.142) | 0.033 (−0.037, 0.102) |

| linear-trend, P-value | 0.034 | 0.300 | 0.043 | 0.129 | 0.059 | 0.368 |

| Mediscore | ||||||

| T1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| T2,β (Confidence interval) | 0.039 (−0.032, 0.110) | −0.004 (−0.078, 0.070) | 0.032 (−0.032, 0.096) | 0.015 (−0.046, 0.076) | −0.034 (−0.099, 0.030) | 0.013 (−0.050, 0.076) |

| T3,β (Confidence interval) | 0.062 (−0.017, 0.141) | 0.028 (−0.053, 0.110) | 0.065 (−0.006, 0.136) | 0.062 (−0.003, 0.127) | 0.041 (−0.030, 0.113) | 0.034 (−0.036, 0.104) |

| linear-trend, P-value | 0.113 | 0.551 | 0.070 | 0.072 | 0.392 | 0.341 |

| Dashscore | ||||||

| T1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| T2,β (Confidence interval) | 0.017 (−0.052, 0.087) | 0.022 (−0.049, 0.094) | 0.055 (−0.007, 0.117) | 0.028 (−0.032, 0.088) | −0.00057 (−0.065, 0.064) | 0.0048 (−0.056, 0.066) |

| T3,β (Confidence interval) | 0.043 (−0.032, 0.118) | 0.036 (−0.042, 0.113) | 0.052 (−0.016, 0.120) | 0.031 (−0.038, 0.099) | 0.027 (−0.044, 0.099) | 0.030 (−0.037, 0.097) |

| linear-trend, P-value | 0.263 | 0.367 | 0.123 | 0.359 | 0.462 | 0.377 |

Adjustments – age, sex, education, APO-E4, late life cog act, caloric intake, physical activity, & smoking; Italicized and bold – statistically significant: Italicized – approaching significance

Discussion

Although an extensive body of literature exists on the role of diet in stroke prevention, relatively few studies have examined the role of diet on cognitive decline post-stroke, even though stroke nearly doubles the risk of dementia (3). In the present study, we observed a community cohort of older persons with a clinical history of stroke but no diagnosis of dementia at their baseline enrollment to determine the role that diet may play in preventing post-stroke cognitive decline. In this observational study, we found that the MIND diet significantly slowed the rate of decline in global cognition, as well as in the individual cognitive domains of semantic memory and perceptual speed. The Mediterranean and DASH diets were not associated with slowing global cognitive decline or slowing decline in any of the 5 cognitive domains. This suggests that while the Mediterranean and DASH diets may be useful in preventing stroke and other cardiovascular conditions, the MIND diet, which is specifically tailored for brain health, may be more effective in preventing post-stroke cognitive decline.

Large, prospective cohort studies that established the role of diet in the prevention of cardiovascular disease include the Nurses Health Study, the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study, The Northern Manhattan Study, and The Framingham Heart Study (19–21). A smaller number of randomized controlled trials, such as PREDIMED[22], have also found diet to be effective in the prevention of cardiovascular outcomes including stroke. Fewer data exist on the role of diet in secondary stroke prevention, although several studies such as ONTARGET, TRANSCEND (23) and the Lyon Heart Study (24) have shown that diet may be a valuable target in secondary stroke prevention as well, with some studies suggesting that diet may provide an effect size similar to that of statins (25).

Despite separate studies advocating the role of diet both in stroke prevention and the prevention of cognitive decline, most of these studies did not examine the role of diet in preventing cognitive decline in subjects with a history of stroke specifically, a population that is at higher risk for dementia than the general population. In fact, many of the existing large observational cohort studies have excluded subjects with a clinical history of stroke at baseline (20).

The MIND diet, which is a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, was designed to emphasize nutrients that have been associated with dementia prevention and to discourage elements, such as saturated/hydrogenated fats, that have been associated with dementia (4). The MIND diet recommends greater than or equal to 3 servings of whole grain per day (26), greater than or equal to 6 servings of leafy green vegetables per week (in addition to one or more daily servings of other vegetables) (27), greater than or equal to 2 servings of berries per week (28), greater than or equal to one serving of fish per week (29), greater than or equal to 2 servings of poultry per week, greater than 3 servings of beans per week, and greater than or equal to 5 servings of nuts per week (30). The MIND diet recommends that olive oil be used as the primary source of fat (31, 32) and allows one serving of alcohol/wine per day (33). The following food items are discouraged by the MIND diet: red meat and products, less than 4 servings per week; fast food and fried food, less than one serving per week; butter/margarine, less than 1tsp per day; cheese, less than once per week; and pastries/sweets, less than 5 servings per week.

The MIND diet is a rich source of many different dietary components that have been linked to brain health, including vitamin E, folate, n-3 fatty acids, carotenoids, and flavonoids. Multiple prospective cohort studies have shown that avoiding saturated and trans-unsaturated (hydrogenated) fats and increasing the consumption of antioxidant nutrients and B-vitamins are associated with slower rates of cognitive decline (34–36). The emphasis on the consumption of berries vs. fruit in general was based on findings from multiple epidemiological studies of cognition, showing that, whereas overall fruit consumption does not appear to impart a protective effect (27, 37–39), the subtype of fruit, berries, does appear to slow cognitive decline (28). Vegetables, and leafy green vegetables in particular, have also been shown in several large prospective studies to reduce cognitive decline (27, 37).

The Mediterranean diet has been widely studied (40, 41) and recommends greater than or equal to 4 tablespoons of olive oil per day, 3 or more servings of tree nuts and peanuts per week, 3 or more servings of fruit per day, 2 or more servings of vegetables per day, 3 or more servings of fish (particularly fatty fish) per week, 3 or more servings of legumes per week, using white meat as a substitute for red meat, and drinking 1 or more glasses of wine with meals, 7 or more times per week. The Mediterranean diet limits soda to less than one per day, consumption of commercial baked goods, sweets, and pastries to less than 3 per week; spreadable fats to less than 1 per day; and red and processed meats to less than once per day.

The Mediterranean diet was associated with higher cognitive scores in a sub-study of PREDIMED[31], a randomized trial designed to test diet effects on cardiovascular outcomes among Spaniards at high cardiovascular risk. In our study, although the Mediterranean diet was associated with slower rates of global cognitive decline in the age-adjusted model, this association became nonsignificant when basic adjustments for sex, education, APOE-ε4, late-life cognitive activity, caloric intake, physical activity, and smoking were applied.

The DASH diet was not associated with slower rates of cognitive decline in our study, although prior studies have shown this diet to be effective for prevention of both cognitive decline (26, 42, 43) and stroke prevention (44).

This study has several limitations, the most important of which is that it is observational in nature; as such, it cannot claim a cause and effect relationship. While replication in other observational cohort studies would be useful to confirm the associations seen in this study, a diet intervention trial in stroke survivors is needed to establish a causal role between diet and post-stroke cognition. Another limitation of this study is its small sample size resulting in low power to observe associations. It may be possible to observe protective associations of the DASH and Mediterranean diets on cognitive decline in larger stroke populations. Nonetheless, many larger observational cohort studies examining the role of nutrition on cognitive decline have excluded subjects with a clinical history of stroke. Therefore, we believe that this is an important and under-studied population that may be disproportionately prone to developing dementia, and preliminary data are important to guide future studies.

Clinical history of stroke was determined by self-report or by diagnosis during an annual clinical neurologic examination, but the lack of MRI or CT to confirm this diagnosis or to differentiate between stroke sub-type is a limitation. Subjects with a clinical history of mild stroke or a radiographic infarct may have been excluded from our sample, but the Framingham Offspring Study found that individuals with silent cerebral infarcts have similar risk profiles to those with a clinical history of stroke (45). We suspect that the inclusion of these individuals in our analysis would have been more likely to strengthen our findings than to invalidate them. Other large prospective observational cohort studies, such as the Nurses Health Study (46) have employed questionnaires and clinical evaluations to identify cardiovascular outcomes, and suggested that self-reported stroke is a valid approach to assessing the prevalence of stroke in a population (47–49). In the Tromso Study, researchers followed up with 213 individuals who had self-reported histories of stroke at a community health fair and found that upon more intensive evaluation (physician examination and review of medical records, including neuroimaging) 79.2% of self-reported strokes were confirmed (47). Self-reported stroke was found to have a similar prognostic value for predicting recurrent stroke in the Health in Men Study, and the authors concluded that self-reported stroke may be useful in further epidemiological studies (49).

The MAP cohort is an older, predominantly non-Hispanic white population, so findings should not be generalized to other ethnic groups or younger cohorts. The dietary questionnaires had limited questions regarding some of the dietary components and information on frequency of consumption. For example, a single item each provided information on the consumption of nuts, berries, beans, and olive oil. This study’s strengths include the use of a validated food questionnaire for comprehensive dietary assessment, the measurement of cognitive change with a large battery of standardized tests annually for up to 10 years, and statistical control of the important confounding factors.

The MIND diet is a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, with additional emphasis on the nutritional components that have been shown to optimize brain health. The MIND diet has previously been shown to slow cognitive decline in the general population in an observational cohort study,[4] but it was unclear whether this association would remain strong for subjects with a clinical history of stroke. This observational study suggests that not only is the MIND diet strongly associated with slowing cognitive decline post-stroke, its estimated effect was twice the size of that observed in the overall MAP cohort (41). Additionally, the MIND diet appeared superior to the Mediterranean and DASH diets in slowing cognitive decline in stroke survivors. Given the projected burden of stroke and dementia in an aging population, further studies are warranted to explore the role of the MIND diet in preventing cognitive decline in stroke survivors. High adherence to the MIND diet was associated with slower rates of cognitive decline in an observational study of older adults with a clinical history of stroke.

Funding:

Supported by grants from the NIA (R01 AG054476 and R01AG17917). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Financial Disclosures: Laurel Cherian: Study concept and design, Interpretation of data, and writing of manuscript. Dr. Cherian reports no disclosures. Yamin Wang: Analysis and interpretation. Dr. Wang reports no disclosures. Keiko Fakuda: Background research and initial draft of introduction and discussion. Ms. Fakuda reports no disclosures. Sue Leurgans: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Leurgans reports no disclosures. Neelum Aggarwal: Study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Aggarwal reports no disclosures. Martha Clare Morris: Study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Morris reports no disclosures.

Ethical standards: The authors attest that they have provided an accurate account of the work performed as well as an objective discussion of its significance. Relevant raw data has been accurately provided. The authors attest that the work is original and has not been published elsewhere. Pertinent work from other sources has been appropriately cited. The Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

References

- 1.Schellinger PD, et al. , Assessment of additional endpoints for trials in acute stroke - what, when, where, in who? Int J Stroke, 2012. 7(3): p. 227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saver JL, Time is brain--quantified. Stroke, 2006. 37(1): p. 263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portegies ML, et al. , Prestroke Vascular Pathology and the Risk of Recurrent Stroke and Poststroke Dementia. Stroke, 2016. 47(8): p. 2119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris MC, et al. , MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement. 11(9): p. 1015–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris MC, et al. , MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 11(9): p. 1007–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarmeas N, et al. , Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA, 2009. 302(6): p. 627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangney CC, et al. , Adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern and cognitive decline in a community population. Am J Clin Nutr, 2011. 93(3): p. 601–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DA, et al. , Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2012. 9(6): p. 646–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson RS, et al. , Odor identification and decline in different cognitive domains in old age. Neuroepidemiology, 2006. 26(2): p. 61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris MC, et al. , Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire by cognition in an older biracial sample. Am J Epidemiol, 2003. 158(12): p. 1213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panagiotakos DB, et al. , Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med, 2007. 44(4): p. 335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein DE, et al. , Determinants and consequences of adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet in African-American and white adults with high blood pressure: results from the ENCORE trial. J Acad Nutr Diet, 2012. 112(11): p. 1763–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett DA, et al. , Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis, 2018. 64(s1): p. S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson RS, et al. , Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2005. 11(4): p. 400–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchman AS, et al. , Physical activity and motor decline in older persons. Muscle Nerve, 2007. 35(3): p. 354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohout FJ, et al. , Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health, 1993. 5(2): p. 179–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchman AS, et al. , Apolipoprotein E e4 allele is associated with more rapid motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 2009. 23(1): p. 63–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett DA, Secular trends in stroke incidence and survival, and the occurrence of dementia. Stroke, 2006. 37(5): p. 1144–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fung TT, et al. , Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation, 2009. 119(8): p. 1093–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsivgoulis G, et al. , Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and prediction of incident stroke. Stroke. 46(3): p. 780–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willey JZ, et al. , Lipid profile components and risk of ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS). Arch Neurol, 2009. 66(11): p. 1400–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Estruch R, et al. , Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 368(14): p. 1279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dehghan M, et al. , Relationship between healthy diet and risk of cardiovascular disease among patients on drug therapies for secondary prevention: a prospective cohort study of 31 546 high-risk individuals from 40 countries. Circulation, 2012. 126(23): p. 2705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lorgeril M, et al. , Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation, 1999. 99(6): p. 779–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dearborn JL, Urrutia VC, and Kernan WN, The case for diet: a safe and efficacious strategy for secondary stroke prevention. Front Neurol, 2015. 6: p. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wengreen H, et al. , Prospective study of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension- and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging. Am J Clin Nutr, 2013. 98(5): p. 1263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris MC, et al. , Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change. Neurology, 2006. 67(8): p. 1370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devore EE, et al. , Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann Neurol, 2012. 72(1): p. 135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris MC, et al. , Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study. Arch Neurol, 2005. 62(12): p. 1849–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urpi-Sarda M, et al. , Virgin olive oil and nuts as key foods of the Mediterranean diet effects on inflammatory biomakers related to atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Res. 65(6): p. 577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Lapiscina EH, et al. , Mediterranean diet improves cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2013. 84(12): p. 1318–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razquin C, et al. , A 3 years follow-up of a Mediterranean diet rich in virgin olive oil is associated with high plasma antioxidant capacity and reduced body weight gain. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2009. 63(12): p. 1387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larrieu S, et al. , Nutritional factors and risk of incident dementia in the PAQUID longitudinal cohort. J Nutr Health Aging, 2004. 8(3): p. 150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris MC, Nutritional determinants of cognitive aging and dementia. Proc Nutr Soc, 2012. 71(1): p. 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillette Guyonnet S, et al. , IANA task force on nutrition and cognitive decline with aging. J Nutr Health Aging, 2007. 11(2): p. 132–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris MC and Tangney CC, Dietary fat composition and dementia risk. Neurobiol Aging, 2014. 35 Suppl 2: p. S59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang JH, Ascherio A, and Grodstein F, Fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive decline in aging women. Ann Neurol, 2005. 57(5): p. 713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nooyens AC, et al. , Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive decline in middle-aged men and women: the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Br J Nutr, 2011. 106(5): p. 752–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X, Huang Y, and Cheng HG, Lower intake of vegetables and legumes associated with cognitive decline among illiterate elderly Chinese: a 3-year cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging, 2012. 16(6): p. 549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitjavila MT, et al. , The Mediterranean diet improves the systemic lipid and DNA oxidative damage in metabolic syndrome individuals. A randomized, controlled, trial. Clin Nutr 32(2): p. 172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gadgil MD, et al. , The effects of carbohydrate, unsaturated fat, and protein intake on measures of insulin sensitivity: results from the OmniHeart trial. Diabetes Care. 36(5): p. 1132–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solfrizzi V, et al. , Relationships of Dietary Patterns, Foods, and Micro- and Macronutrients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Late-Life Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 59(3): p. 815–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tangney CC, et al. , Relation of DASH- and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology, 2014. 83(16): p. 1410–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folsom AR, Parker ED, and Harnack LJ, Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens, 2007. 20(3): p. 225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das RR, et al. , Prevalence and correlates of silent cerebral infarcts in the Framingham offspring study. Stroke, 2008. 39(11): p. 2929–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fung TT, et al. , Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med, 2008. 168(7): p. 713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engstad T, Bonaa KH, and Viitanen M, Validity of self-reported stroke : The Tromso Study. Stroke, 2000. 31(7): p. 1602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson CA, et al. , Moderate agreement between self-reported stroke and hospital-recorded stroke in two cohorts of Australian women: a validation study. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2015. 15: p. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jamrozik E, et al. , Validity of self-reported versus hospital-coded diagnosis of stroke: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2014. 37(4): p. 256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]