The nuclear permeability barrier depends on closure of nuclear envelope holes. Penfield et al. show that the CNEP-1–lipin pathway limits production of ER membranes that feed into and close nuclear envelope holes. Upon excess membrane production, remodeling by nuclear envelope adaptors to ESCRT-III contributes to nuclear closure.

Abstract

The nuclear permeability barrier depends on closure of nuclear envelope (NE) holes. Here, we investigate closure of the NE opening surrounding the meiotic spindle in C. elegans oocytes. ESCRT-III components accumulate at the opening but are not required for nuclear closure on their own. 3D analysis revealed cytoplasmic membranes directly adjacent to NE holes containing meiotic spindle microtubules. We demonstrate that the NE protein phosphatase, CNEP-1/CTDNEP1, controls de novo glycerolipid synthesis through lipin to prevent invasion of excess ER membranes into NE holes and a defective NE permeability barrier. Loss of NE adaptors for ESCRT-III exacerbates ER invasion and nuclear permeability defects in cnep-1 mutants, suggesting that ESCRTs restrict excess ER membranes during NE closure. Restoring glycerolipid synthesis in embryos deleted for CNEP-1 and ESCRT components rescued NE permeability defects. Thus, regulating the production and feeding of ER membranes into NE holes together with ESCRT-mediated remodeling is required for nuclear closure.

Introduction

The nuclear envelope (NE) is composed of two continuous lipid bilayers (the inner and outer nuclear membranes) separated by a single lumen. The membranes and lumen of the NE are contiguous with the ER, a large interconnected membrane network that extends throughout the cytoplasm. Lipid metabolizing enzymes associated with ER membranes produce the bilayer glycerophospholipids of the NE (Baumann and Walz, 2001; Fagone and Jackowski, 2009; Hetzer, 2010). A subset of integral membrane proteins is enriched at the inner nuclear membrane (INM), giving the NE its unique identity (Hetzer, 2010).

In open mitosis, ER membranes and associated INM proteins wrap the surface of segregated chromosomes to initiate the formation of the NE. Completion of the NE requires closure of holes that coincide with spindle microtubules (MTs), as well as insertion of nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) for transport between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Hetzer, 2010; Ungricht and Kutay, 2017). Assembly of the cytoplasmic protein complexes of endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) III on the negatively curved surface of NE holes constricts membranes to execute fission and seal the NE (Olmos et al., 2015; Vietri et al., 2015). The ESCRT-II/III hybrid protein CHMP7 and the INM protein LEM2 form a complex at NE holes to recruit ESCRT-III components (Olmos et al., 2016; Webster et al., 2016; Gu et al., 2017). Subsequent recruitment of the MT-severing AAA-ATPase, spastin, coordinates mitotic spindle disassembly with membrane fission (Vietri et al., 2015). This sealing process restricts traffic to the NPCs through which molecules greater than ∼40 kD cannot diffuse passively (Wente and Rout, 2010; Ungricht and Kutay, 2017). Without ESCRT-mediated NE sealing, ∼40–60 nm holes occupied by spindle MTs persist and cause slow nucleocytoplasmic mixing, abnormal nuclear morphologies, and DNA damage (Olmos et al., 2015; Vietri et al., 2015; Olmos et al., 2016; Ventimiglia et al., 2018).

In interphase, NE ruptures that cause rapid mixing of nuclear and cytoplasmic components, and at times nuclear entry of whole organelles, recruit ESCRT-III during repair (De Vos et al., 2011; Vargas et al., 2012; Denais et al., 2016; Raab et al., 2016). Even micron-scale punctures caused by lasers undergo slow repair (Denais et al., 2016; Penfield et al., 2018; Halfmann et al., 2019). Given the evidence that the ESCRT-III spiral filament (CHMP4B/VPS-32/Snf7) resolves holes of ∼30–50 nm in diameter (Wollert and Hurley, 2010; Olmos et al., 2015, 2016; McCullough et al., 2018), it is unclear how large NE holes narrow after NE rupture or after open mitosis. ESCRT-III or the NE-specific adaptors for ESCRT-III, CHMP7 and LEM2, may contribute to constricting large NE openings, although currently evidence for this does not exist.

Contiguous ER membranes are a potential source to narrow large NE openings. In the rapid cell cycles of Drosophila embryos, specialized ER membrane sheets containing preassembled NPCs flow into NE openings to facilitate nuclear expansion during interphase (Hampoelz et al., 2016). However, the source of the membrane to close NE openings at the end of mitosis or after rupture is not known.

From yeast to metazoans, spatial regulation of glycerolipid synthesis limits incorporation of membranes into the NE, and lipin is the key enzyme controlling the production of glycerolipids in the ER/NE network (Siniossoglou, 2013; Bahmanyar, 2015). Lowering of lipin activity causes NE expansion during interphase and closed mitosis in yeast and abnormal nuclear morphologies after open mitosis in Caenorhabditis elegans (Tange et al., 2002; Santos-Rosa et al., 2005; Golden et al., 2009; Gorjánácz and Mattaj, 2009; Bahmanyar et al., 2014; Makarova et al., 2016). Lipin dephosphorylates phosphatidic acid to produce diacylglycerol, which is used for the synthesis of the main structural glycerophospholipids, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine, as well as for triglycerides for lipid storage, at the expense of the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol (PI; Han et al., 2006; Siniossoglou, 2013; Bahmanyar, 2015). Lipin is activated by the integral membrane phosphatase CTDNEP1/CNEP-1/Nem1 of the NE (Santos-Rosa et al., 2005; O’Hara et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007; Grimsey et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2011; Han et al., 2012; Bahmanyar et al., 2014). In C. elegans embryos, CNEP-1 activates lipin at the NE to limit PI production. Increased PI levels in CNEP-1–deleted embryos cause the formation of ectopic ER sheets that wrap around the permeabilized NE upon entry into mitosis (Bahmanyar et al., 2014). Whether activation of lipin by CTDNEP1/CNEP-1 at the NE is involved in closure of NE openings during NE formation had not been tested.

We analyzed the closure of the micron-scale-sized NE opening surrounding the meiotic spindle in C. elegans to demonstrate a role for glycerolipid synthesis through CNEP-1 activation of lipin in nuclear closure. In cnep-1 mutants, ER membranes invade the nuclear interior at sites of nuclear closure to disrupt the NE permeability barrier. The NE adaptors for ESCRTs restrict ER membrane invasion at NE holes to promote nuclear closure. 3D analysis revealed contiguous cytoplasmic membranes that contact the NE nearby holes containing meiotic spindle MTs. We propose that nuclear closure in metazoans requires the CNEP-1–lipin pathway to coordinate the production of ER membranes with the feeding and remodeling of ER membranes to narrow NE holes.

Results and discussion

We analyzed the role of NE adaptors for ESCRT-III in C. elegans during NE closure by monitoring the highly asymmetric closure of the NE around the acentriolar MT spindle during oocyte meiosis. Fertilization by haploid sperm triggers oocytes that are arrested in prophase of meiosis I to undergo two rounds of meiotic chromosome segregation. An acentriolar meiotic spindle surrounds sister chromatids (Albertson and Thomson, 1993; Oegema and Hyman, 2006; Fabritius et al., 2011) and transitions into a central spindle of MTs between the segregated chromosomes (“maximal spindle shortening,” Fig. 1 A; Yang et al., 2003; Fabritius et al., 2011; Redemann et al., 2018). After anaphase II, the haploid, oocyte-derived pronucleus forms as the MTs elongate and dissipate (Yang et al., 2003; Fabritius et al., 2011; Redemann et al., 2018), but the mechanisms of remodeling and sealing the NE were not known.

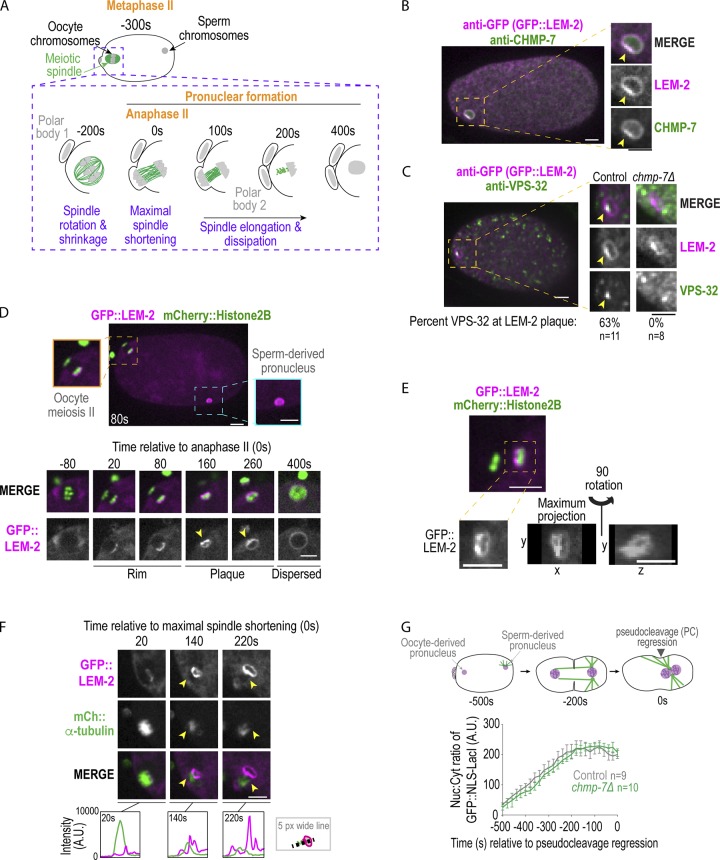

Figure 1.

ESCRT-III components form a plaque adjacent to the meiotic spindle, but are not required for nuclear closure. (A) Schematic of C. elegans oocyte meiosis II. (B and C) Fixed overview and magnified images of C. elegans oocytes expressing GFP::LEM-2 immunostained for GFP and CHMP-7 (B) or VPS-32 (C). LEM-2 examples in C are not scaled to the same intensity. Arrowheads mark plaque. Percentage of oocyte-derived pronuclei in which VPS-32 is localized to plaque marked by GFP::LEM-2 is shown. (D) Confocal images of embryo and of time lapse series of oocyte meiosis II with indicated markers. Arrowheads mark LEM-2 plaque. (E) Confocal image of C. elegans oocyte meiosis II with indicated markers. Below, magnified images of GFP::LEM-2. (F) Confocal images from time series of oocyte meiosis II with indicated markers. Arrowheads mark LEM-2 plaque. Below, line scans measuring background-corrected fluorescent intensities in arbitrary units (A.U.). (G) Schematic stereotypical nuclear events in early embryos relative to regression of the pseudocleavage, used as a reference time point 0 s (Penfield et al., 2018). Plot of nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio of GFP::NLS-LacI for the indicated conditions. A.U., arbitrary units. Average ± SEM is shown. n = no. of embryos. Scale bars, 5 µm.

The NE adapter for ESCRT-III, LEM-2 tagged with GFP, marks the nuclear rim and forms a “plaque” on the oocyte-derived pronucleus (Fig. 1, B–F). CHMP-7 and the ESCRT-III spiral component VPS-32 colocalize with the LEM-2 plaque (Fig. 1, B and C), and targeting of VPS-32 to the plaque requires CHMP-7 (Fig. 1 C and Fig. S1 A). Live imaging revealed that GFP::LEM-2 initially appears at anaphase II on the chromatin surface farthest from the extruding polar body (Fig. 1 D and Fig. S1 B, 28 ± 14 s, average ± SD relative to anaphase II onset, n = 9), accumulates into a plaque opposite the initial rim ∼180 s after anaphase II (Fig. 1 D and Fig. S1 B, 182 ± 32, n = 9), and then disperses ∼200 s later into a uniform rim around the oocyte-derived pronucleus (Fig. 1 D and Fig. S1 B, 197 ± 74 s, average duration ± SD of plaque, n = 7). The GFP::LEM-2 plaque in meiosis II is adjacent to the meiotic spindle (Fig. S1 C), and the accumulation of the GFP::LEM-2 plaque correlates with loss of fluorescence signal of GFP::α-tubulin at the meiotic spindle (Fig. 1 F, compare 140 s to 220 s; Video 1). The general ER membrane marker (SP12::GFP) did not form a plaque on the oocyte-derived pronucleus (Fig. S1 D), and LEM-2 did not form a plaque on the sperm-derived pronucleus (Fig. 1 D). In 20% of the cases (n = 20), openings are visible within the GFP::LEM-2 plaque and are ∼1 µm in diameter (Fig. 1 E, maximum projection), which were also occasionally observed at large openings caused by NE rupture (Fig. S1 E). However, deletion of chmp-7 did not impact the nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio of a GFP::NLS (Nuclear Localiziation Signal) reporter (Fig. 1 G, GFP::NLS-LacI), so ESCRT-III is not required for narrowing of the large hole. Therefore, there may be/ a redundant pathway to close NE openings and restrict nucleocytoplasmic exchange in C. elegans oocytes.

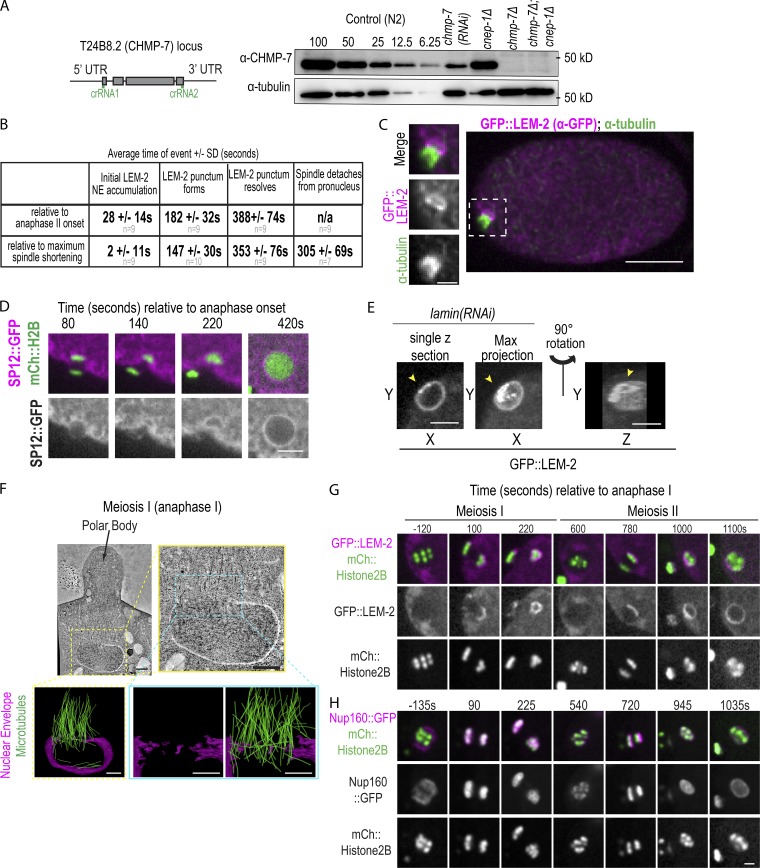

Figure S1.

Nuclear membranes asymmetrically enclose oocyte chromatin during nuclear formation after meiosis, related to Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. (A) Left: CRISPR strategy used to generate deletion in T24B8.2 (chmp-7) locus, a gene predicted to encode the orthologue of human CHMP7. crRNAs used are shown in green. Right: Immunoblot probed for CHMP-7 and α-tubulin. A dilution series of control (N2) worm lysate from 100% to 6.25% and 100% of lystate and chmp-7 (RNAi) and deletions for the indicated genetic backgrounds. (B) Table of time in seconds (average ± SD) of indicated events relative to chromosome segregation (anaphase II onset) or maximal spindle shortening. n = no. of embryos. (C) Fixed C. elegans embryo stained for GFP::LEM-2 (magenta) and α-tubulin (green). Magnified images on the left are of the oocyte-derived pronucleus. (D) Confocal images from a time lapse series of a C. elegans oocyte in meiosis II expressing SP12::GFP and mCherry::Histone2B. Representative example of n = 5 embryos is shown. Time is in seconds relative to anaphase II onset. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Single z-slice, max z-projection, and a 3D-projection of rupture site in a sperm-derived pronucleus depleted of lamin expressing GFP::LEM-2. Arrowheads mark a gap between the GFP::LEM-2 plaque that has formed at a NE rupture site. (F) Tomographic slice of C. elegans oocyte in mid-anaphase I and a magnified image of oocyte-derived pronucleus from the z-slice on the right. Below are 3D models of this region of the electron tomogram traced for nuclear membranes (magenta) and MTs (green). Scale bars, 500 nm. (G and H) Confocal images from time lapse series of the oocyte-derived pronuclei in meiosis I and II either expressing GFP::LEM-2 and mCherry::Histone2B (G) or expressing Nup160::GFP and mCherry::Histone2B (H). Time is in seconds relative to anaphase I onset. Scale bar, 2.5 µm.

Video 1.

LEM-2 plaque forms and disperses as the spindle dissipates and detaches from the oocyte-derived pronucleus, related to Fig. 1. C. elegans oocyte in meiosis II expressing GFP::LEM-2 and mCherry::α-tubulin. Arrows mark initial GFP::LEM-2 rim and the formation of the GFP::LEM-2 plaque. The video starts at −100 s before maximal spindle shortening and mages were acquired every 20 s, and the playback rate is 60× real time. Scale bar, 10 µm.

To determine how the NE opening occluded by the meiotic spindle closes, we analyzed serial sections of oocytes from electron tomograms of mid-meiosis I and of late meiosis I and II. In both meiosis I and II, the region occupied by the spindle is largely devoid of cytoplasmic membranes, and nuclear membranes wrap chromatin but are discontinuous in the spindle region (Fig. S1 F; and Fig. 2, A and B). Electron-dense structures resembling NPCs were only observed in the region of the NE opposite the spindle in the meiosis II tomogram, as expected from fluorescent imaging of Nup160::GFP (Fig. S1, F–H; and Fig. 2, A and B). In mid-meiosis I, a large NE gap (Fig. S1 F and Video 2, 0.85 µm × 1.5 µm in this example) coincides with spindle MTs and contains a segment with a few discontinuous membranes. In late meiosis I, nuclear membranes facing the meiotic spindle are more continuous (largest diameter of nuclear gap: ∼400 nm) and contain a few remaining spindle MTs that occupy holes with an average diameter of 133 nm (60–320 nm; n = 8 gaps, Fig. S2 A and Video 3). This time point revealed cytoplasmic membrane structures (n = 14) that appear to feed into NE holes containing a MT within this region (Fig. S2 A and Video 3). 71% (n = 14) of cytoplasmic membranes that contacted the NE in the region facing the meiotic spindle were associated with NE holes. Thus, in meiosis I, the large opening occluded by the spindle transitions into smaller NE gaps that contain single MTs and are directly adjacent to cytoplasmic membrane structures.

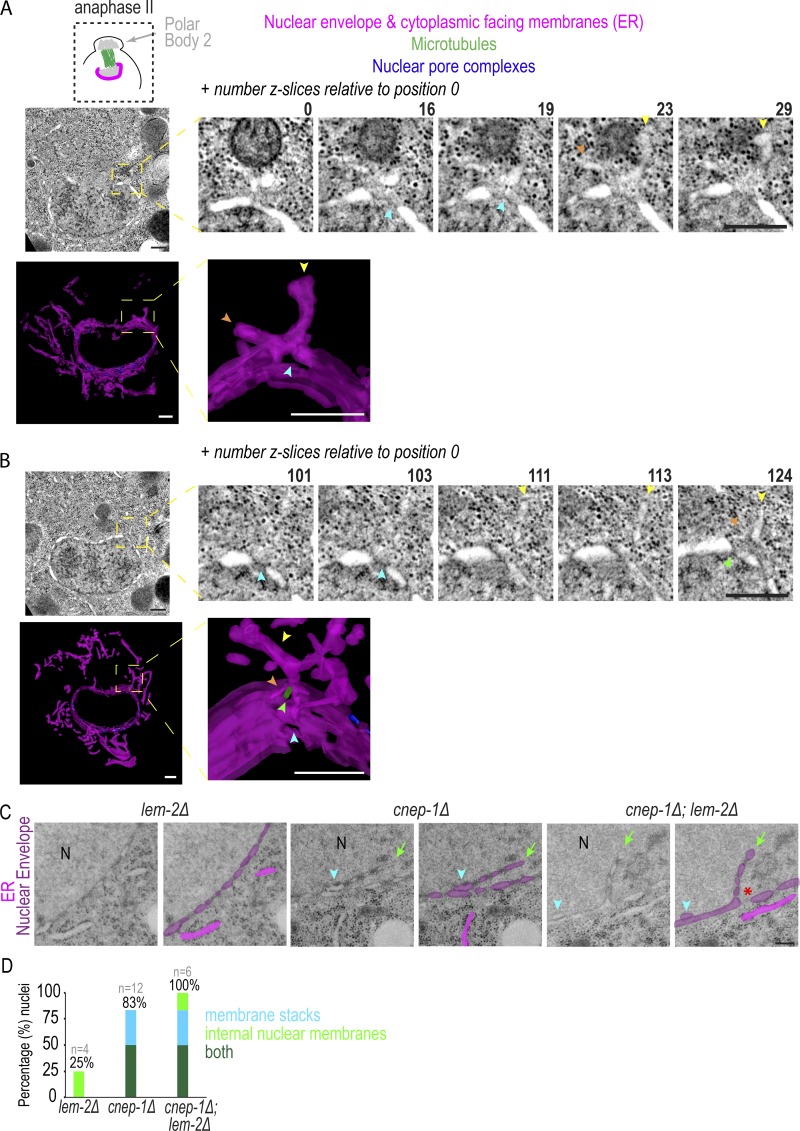

Figure 2.

Cytoplasmic membrane structures are directly adjacent to NE holes occupied by meiotic spindle MTs. (A and B) Top: Z-slices from electron tomograms of an oocyte-derived pronucleus in anaphase of meiosis II. z-slices are relative to position 0. Bottom: 3D models with membranes (magenta) traced. Arrowheads mark membrane sheets (yellow and orange), NE holes (blue), and MTs (green). (C) Representative traced and untraced transmission electron micrographs for indicated conditions is shown. N notes the nuclear interior, arrowhead marks two parallel lumens, and arrow marks NE extension. (D) Plot of frequency of indicated NE phenotypes in transmission electron micrographs, n = no. of nuclei. Scale bars, 250 nm.

Video 2.

Electron tomogram of oocyte-derived pronucleus in mid-anaphase I, related to Fig. S1. Region of electron tomogram of C. elegans oocyte in mid-anaphase I that was traced in Fig. S1 F. Playback rate is 20 z-slices per second. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Figure S2.

CNEP-1 restricts nuclear membrane incorporation during NE sealing processes, related to Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. (A) Overview image from an electron tomogram in late anaphase I. Scale bar, 500 nm. To the right are two regions of the electron tomogram where the z-slices are shown. Number indicates spacing between the z-slices. On the far right are 3D models from the two regions where the nuclear and cytoplasmic membranes (magenta) and MTs (green) intersecting the nuclear holes are traced. Scale bars, 250 nm. (B) Schematics of the cnep-1 and lem-2 gene loci and the deletion alleles used in this study. (C) Example regions with stacked parallel nuclear membrane sheets (yellow arrowheads) that are in close proximity to cytoplasmic membranes that contact the NE in electron tomograms from meiosis I and II. Scale bar, 100 nm. To the right are the fraction of regions with parallel stacked nuclear membrane sheets. N = no. of regions with cytoplasmic-nuclear membrane contacts. (D) Confocal images from a time lapse series of oocytes expressing GFP::LEM-2 for the indicated conditions. Green arrowhead marks GFP::LEM-2 plaque, and yellow arrowheads mark internal membrane extension. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. Below is the percent of nuclei with GFP::LEM-2 marked internal nuclear membranes at the time of NE formation after meiosis II. (E) Confocal images of sperm-derived pronuclei from time lapse series of embryos expressing GFP::LEM-2 Scale bar, 2.5 µm. To the right are percentages of pronuclei that have interior nuclear membranes marked with GFP::LEM-2 for the indicated conditions. Yellow arrowheads mark GFP::LEM-2 plaque and internal membrane extensions. n = number of embryos. (F) Average ± SD time (seconds) of events relative to anaphase II onset for control and cnep-1Δ embryos scored from time lapse series of embryos expressing GFP::LEM-2 and mCherry::Histone2B, n = no. of embryos. (G) Plot of individual times (seconds) that the meiotic spindle marked with GFP::α-tubulin no longer is adjacent to the chromatin of the oocyte-derived pronucleus. Time is relative to anaphase II onset. (H) Confocal images of the oocyte-derived pronucleus from fixed embryos probed for CHMP-7 and also GFP::LEM-2 (not shown) for the indicated conditions. To the right are the percent of embryos with CHMP-7 or VPS-32 accumulation at the GFP::LEM-2 plaque for the indicated conditions, n = no. of embryos.

Video 3.

Electron tomogram of oocyte-derived pronucleus in late-anaphase I, related to Fig. S2. Region of electron tomogram of C. elegans in late anaphase I that is shown and traced in Fig. S2 A. Playback rate is 20 z-slices per second. Scale bar, 500 nm.

The region occupied by the spindle in electron tomograms of meiosis II also contained cytoplasmic membranes contacting the NE directly adjacent to NE holes (Fig. 2, A and B). 73% (n = 15) of these cytoplasmic structures were associated with a NE hole. This region was mostly devoid of densities resembling NPCs, and so these holes were either unoccupied or contained a MT (Fig. 2, A and B). In one example, a 90-nm hole was surrounded by a cytoplasmic sheet that contacted the NE at sites surrounding the NE opening (Fig. 2 A, Video 4, and Video 5). In a different example, a cytoplasmic membrane overlaid several holes, and contacted a MT occupying a hole (Fig. 2 B, Video 6, and Video 7). Thus, in both late meiosis I and II, cytoplasmic membranes are positioned directly adjacent to small holes in the spindle region. Some of these holes contain MTs and appear contiguous with the NE, suggesting that lateral flow of membranes may narrow remaining NE holes to promote nuclear closure.

Video 4.

Electron tomogram of oocyte-derived pronucleus in anaphase II, related to Fig. 2. Region of electron tomogram of C. elegans in anaphase II that is shown in Fig. 2 A. Playback rate is 20 z-slices per second. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Video 5.

3D model of region of tomogram in Video 4, related to Fig. 2. The NE (magenta) is oriented with the region facing the extruding polar body at the top of the image. Cytoplasmic membranes (magenta) and nuclear pore complexes (blue) are also traced. The model is rotated and magnified on a NE hole facing the spindle that is overlaid by a cytoplasmic sheet. Scale bar, 250 nm.

Video 6.

Electron tomogram of oocyte-derived pronucleus in late-anaphase II, related to Fig. 2. Region of electron tomogram of C. elegans in anaphase II that is shown in Fig. 2 B. Playback rate is 20 z-slices per second. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Video 7.

3D model of region of tomogram in Video 6 related to Fig. 2 The NE (magenta) is oriented with the region facing the extruding polar body at the top of the image. Cytoplasmic membranes (magenta), NPCs (blue) and a MT (green) are also traced. The model is rotated and magnified in on a region with several NE holes facing the spindle that is in close proximity to a cytoplasmic sheet. Scale bar, 250 nm.

Our previous observation of excess ER membrane sheets proximal to NE openings in cnep-1 mutant embryos during mitosis (Bahmanyar et al., 2014) suggested that CNEP-1 may regulate membranes that flow into NE holes. To test this idea, we analyzed transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of interphase nuclei of C. elegans embryos in cnep-1Δ and lem-2Δ mutants alone and cnep-1Δ; lem-2Δ double mutants (Fig. 2, C and D; and Fig. S2 B). Interphase NEs in cnep-1Δ and cnep-1Δ;lem-2Δ double mutants contained NE regions in which two lumens could be traced (Fig. 2, C and D). These membrane stacks were frequently located near large NE gaps that were only present in the cnep-1Δ;lem-2Δ double mutants (3/6 nuclei) and correlated with membrane extensions that stemmed from the nuclear rim and invaded the nuclear interior (hereafter “internal nuclear membranes”; Fig. 2, C and D). The stacked NE membranes were also present in electron tomograms of meiosis I and II in regions near cytoplasmic membrane sheets (Fig. S2 C), so we predict that the redundant parallel membrane sheets may be nuclear membranes displaced by incoming ER.

The fact that internal nuclear membranes were observed in cnep-1Δ mutants and near NE openings in cnep-1Δ;lem-2Δ double mutants suggested that CNEP-1 limits the invasion of ER membranes at NE openings. To test this idea, we imaged an ER marker (SP12::GFP) during post-meiotic NE closure in one-cell embryos. Internal nuclear membranes occurred in 35% of control and 70% of cnep-1Δ oocyte-derived pronuclei and originated from the GFP::LEM-2 plaque (Fig. 3, A and B; and Fig. S2 D). While the control mainly had internal nuclear membranes that partially extended into the nuclear interior (“minor” in Fig. 3 B), the majority of internal nuclear membranes in cnep-1Δ oocyte-derived pronuclei nearly or completely bisected the nucleus (“major” in Fig. 3, A and B; and Video 8). Internal nuclear membranes were not observed in sperm-derived pronuclei (Fig. 3 B), but were observed after NE rupture in lamin-depleted nuclei and were more severe in ruptured nuclei that were also deleted of cnep-1 (Fig. S2 E). Thus, in the absence of CNEP-1, ER membranes invade the nuclear interior at sites of NE closure.

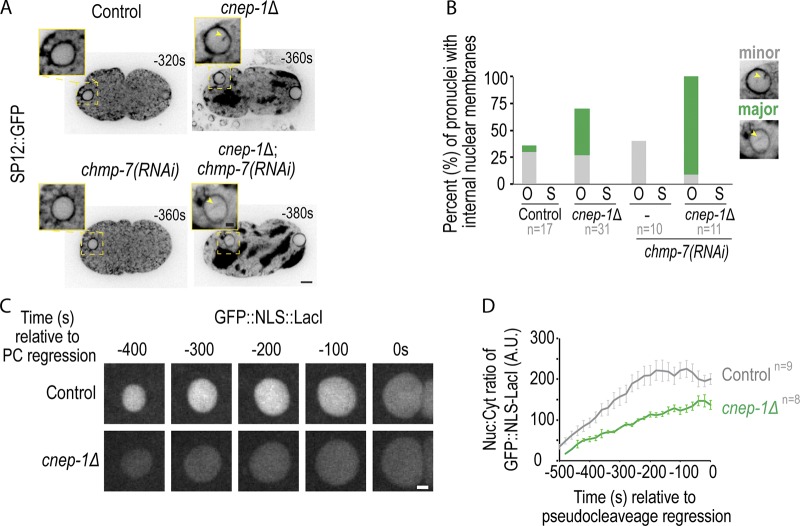

Figure 3.

CNEP-1 promotes nuclear closure after anaphase of meiosis II. (A) Single z-slices of confocal and magnified images of oocyte-derived pronuclei expressing GFP::SP12 (ER marker) from time lapse series of indicated conditions. (B) Plot of percent of oocyte-derived (O) and sperm-derived (S) pronuclei with minor or major internal nuclear membranes with minor as defined in magnified image examples. (C) Confocal images of oocyte-derived pronuclei in indicated conditions. (D) Plot of average ± SEM of nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio of GFP::NLS-LacI for indicated conditions. n = no. of embryos. Scale bars, 2.5 µm.

Video 8.

Internal nuclear membranes after oocyte meiosis II in cnep-1Δ embryos. A control C. elegans embryo (left) and a cnep-1Δ embryo (right) expressing SP12::GFP imaged from shortly after meiosis. Arrow marks internal nuclear membrane. Images were acquired every 20 s, and the playback rate is 60× real time. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Consistent with the increase in severity of membrane stacks and extensions in the transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of cnep-1Δ;lem-2Δ double mutants, the frequency of internal nuclear membranes was exacerbated in oocyte-derived pronuclei of cnep-1Δ embryos RNAi-depleted of chmp-7 (Fig. 3, A and B). These data suggest that LEM-2 and CHMP-7 limit the invasion of ER membranes that are in excess in cnep-1Δ embryos during nuclear closure. Importantly, unlike oocyte-derived pronuclei deleted of chmp-7, oocyte-derived pronuclei in cnep-1Δ mutants are unable to retain GFP::Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) -LacI, indicating that these nuclei contain openings through which imported proteins passively diffuse (Fig. 1 G; and Fig. 3, C and D). While a small NLS reporter leaks out of the NE in cnep-1 mutants, cnep-1Δ pronuclei were able to exclude larger macromolecules since GFP::α-tubulin, which forms an ∼125 kD heterodimer with β-tubulin, is excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 4, A and B). Thus, CNEP-1 may limit the production of ER sheets proximal to the NE to prevent the ER membranes that feed into NE openings from invading the nuclear interior and thereby restrict nuclear transport to NPCs.

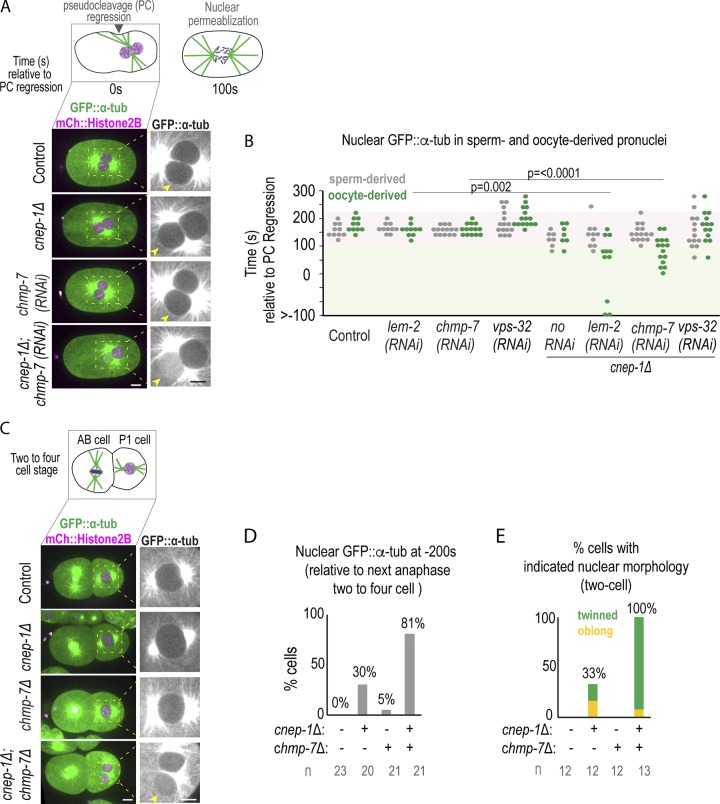

Figure 4.

Loss of NE-adaptors for ESCRTs exacerbates nuclear defects in meiotic and mitotic cnep-1 mutants. (A) Top: Schematic of pronuclear positioning and NE breakdown in the C. elegans zygote relative to pseudocleavage (PC) regression. Bottom: Confocal images of oocytes from time lapse series of embryos for the indicated conditions. Arrowheads mark the oocyte-derived pronucleus. (B) Plot of nuclear entry of GFP::α-tubulin under indicated conditions. P values reported from a Mann–Whitney test. (C) Confocal images of two-cell embryos 240 s before the following anaphase of the P1 cell. (D) Plot of percentage of nuclear entry of GFP::α-tubulin under indicated conditions. n = no. of cells. (E) Plot of percentage of embryos with indicated nuclear phenotypes. n = no. of embryos. Scale bars, 5 µm.

The enhanced severity of internal nuclear membranes and the presence of NE gaps upon deletion of ESCRT components in cnep-1Δ mutant embryos prompted us to test if ESCRTs prevent more severe sealing defects when excess membranes are present. While GFP::α-tubulin enters the nuclear interior only upon mitotic NE permeabilization in control embryos or embryos RNAi-depleted of chmp-7, lem-2, or vps-32 (Fig. 4, A and B; Video 9; Fig. S1 A; and Fig S3 A), nuclear GFP::α-tubulin was observed at significantly earlier time points, and exclusively in the oocyte-derived pronucleus, in cnep-1Δ embryos also RNAi-depleted for chmp-7 or lem-2 (Fig. 4, A and B; and Video 9), but not for vps-32 (Fig. 4 B). ESCRT components localized to the NE in cnep-1 mutants, although there was a mild delay in the onset of ESCRT-dependent events relative to anaphase II (Fig. S2, D and F–H). Together, these data indicate that LEM-2/CHMP-7 contribute to nuclear closure, possibly independently of VPS-32, in cnep-1 mutants to restrict the free diffusion of large proteins across the NE.

Video 9.

CNEP-1 and CHMP7 maintain the NE permeability barrier after oocyte meiosis. C. elegans embryos expressing GFP::α-tubulin for the indicated conditions imaged shortly after meiosis up until NE breakdown. Arrow marks GFP::α-tubulin entry into oocyte-derived pronucleus in cnep-1Δ;chmp-7(RNAi) embryos. Images were acquired every 20 s, and the playback rate is 60× real time. Scale bar, 10 µm.

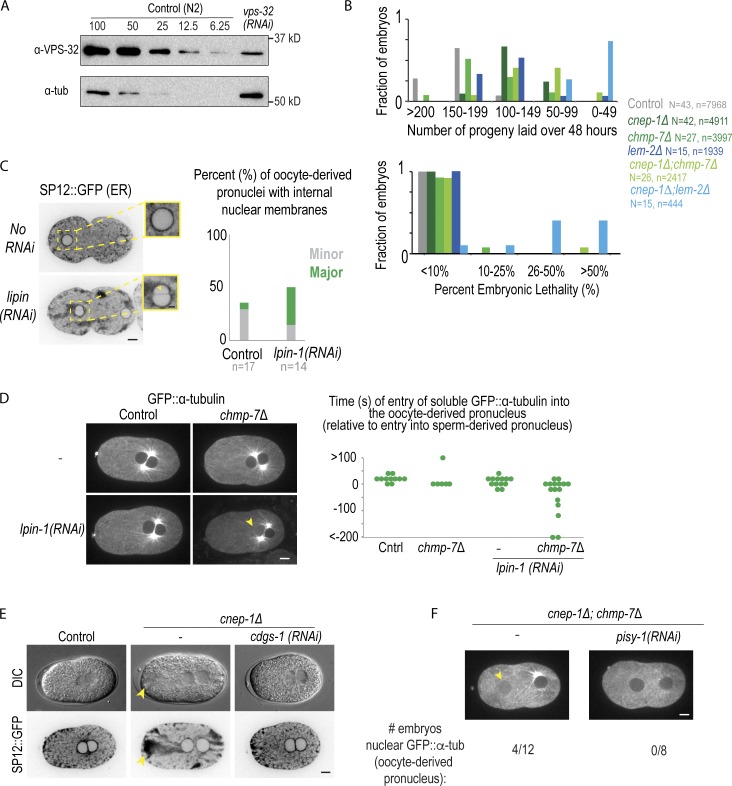

Figure S3.

Depletion of lipin causes internal nuclear membrane and loss of the nuclear permeability barrier in the oocyte-derived pronucleus, related to Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. (A) Immunoblot probing for tubulin and VPS-32 for the indicated conditions. A dilution series of N2 (WT) worm lysate was prepared from 100% to 6.25% of the worm lystate and compared with 100% of the worm lysate of worms depleted for VPS-32 for 48 h. (B) Plot of the fraction of adult worms with the indicated number of progeny laid (above) with the indicated percentage of embryonic lethality (below) ranges over 48 h for the indicated conditions. N = no. of adult worms. n = no. of embryos. (C) Confocal images of C. elegans embryos −180 s before pseudocleavage regression expressing SP12::GFP (an ER marker) from a time-lapse series. Scale bar, 5 µm. Magnified images (right) are of oocyte-derived pronuclei. Arrowhead marks an internal nuclear membrane that bisects the nucleus (“major”). Scale bar, 2.5 µm. Plot (right) of percentage of embryos with “major” and “minor” internal nuclear membranes for indicated conditions. (D) Confocal images from time-lapse series of control and lpin-1 RNAi-depleted C. elegans embryos expressing GFP::α-tubulin at pseudocleavage regression. Arrowhead marks oocyte-derived pronucleus with nuclear soluble GFP::α-tubulin. Scale bar, 5 µm. Right: Plot of times in seconds of the onset of entry of soluble GFP::α-tubulin into the oocyte-derived pronucleus. Time in seconds is relative to when soluble GFP::α-tubulin enters the sperm-derived pronucleus. (E) Representative DIC and fluorescence images of embryos expressing SP12::GFP for the indicated conditions. Yellow arrowhead marks cluster of ER. (F) Confocal images from time lapse series of cnep-1Δ; chmp-7Δ double mutants alone or RNAi-depleted of pisy-1 embryos expressing GFP::α-tubulin at pseudocleavage regression. Below is the fraction of oocyte-derived pronuclei with nuclear soluble GFP::α-tubulin entry before pseudocleavage regression. n = no. of embryos.

CNEP-1 also contributes to closure of NE holes after mitosis. GFP::α-tubulin prematurely accessed the interior of nuclei after mitosis in cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ embryos (Fig. 4, C and D; and Fig. S1 A). The frequency of twinned nuclei observed at this stage, a phenotype that we previously reported to be caused by excessive stacked ER-NE membranes that delay NE breakdown in cnep-1Δ mutants (Bahmanyar et al., 2014), was also enhanced in cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ double mutants (Fig. 4 E). Thus, CNEP-1 and CHMP-7 close the NE and prevent excess nuclear membranes in both mitosis and meiosis. Deletion of chmp-7 or lem-2 in cnep-1Δ mutants results in a greater reduction in brood size and an increased percentage of lethal embryos than either single mutant alone (Fig. S3 B), suggesting that increased severity in nuclear leakiness and abnormal nuclear morphology has adverse consequences on germline development and embryogenesis.

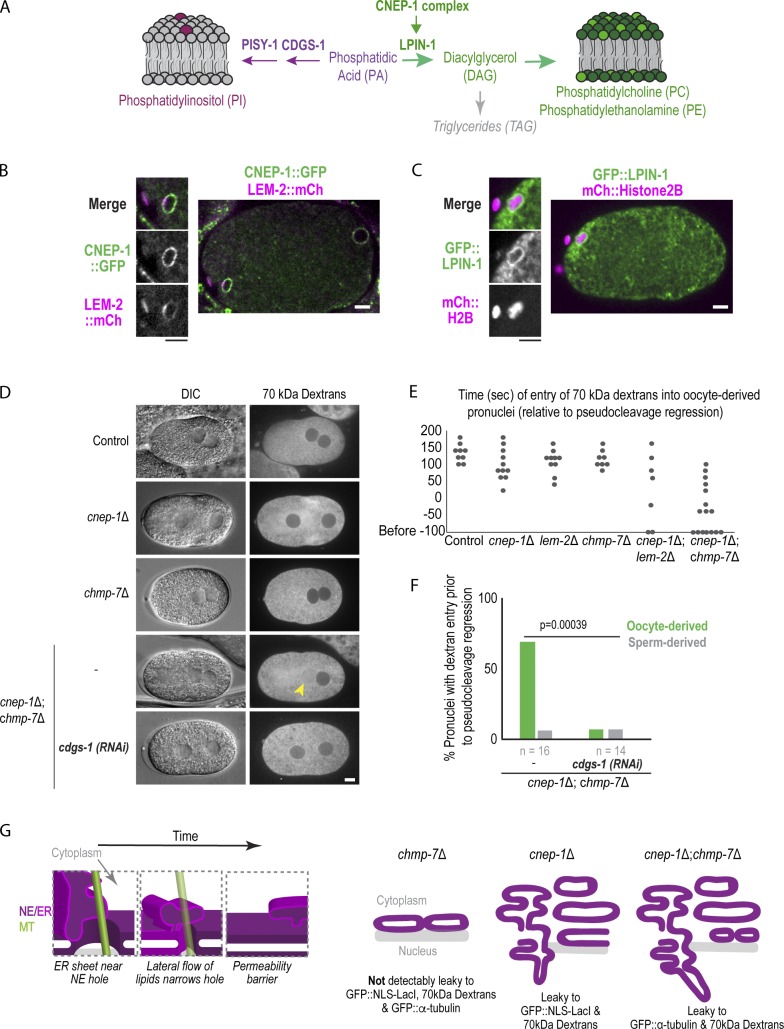

Previous work in early C. elegans embryos showed that CNEP-1 spatially regulates lipin to bias flux away from PI synthesis at the NE and restrict the formation of ER sheets near the NE (Fig. 5 A; Bahmanyar et al., 2014). Consistent with this finding, CNEP-1 was enriched at the NE whereas lipin localized to both the ER and NE in post-meiotic nuclei (Fig. 5, B and C). Partial RNAi depletion of lipin caused major internal nuclear membranes that bisected the oocyte-derived pronucleus (Fig. S3 C), and GFP::α-tubulin only entered the oocyte-derived pronucleus in some of the chmp-7Δ mutant embryos with partial RNAi depletion for lipin (Fig. S3 D). These data suggest that CNEP-1 acts through spatial regulation of lipin to promote NE closure.

Figure 5.

Spatial control of glycerolipid flux promotes nuclear closure. (A) Schematic showing de novo glycerolipid synthesis pathway in metazoans. (B and C) Confocal image of oocyte from time lapse series of oocyte-derived pronucleus expressing CNEP-1::GFP and LEM-2::mCherry in B or GFP::LPIN-1 and mCherry::Histone2B in C. (D) DIC and fluorescence images of embryos from adult worms injected with 70 kD Texas Red dextrans. (E) Plot of nuclear entry of 70-kD dextrans in oocyte-derived pronucleus for the indicated conditions. (F) Percent of pronuclei with dextran entry before pseudocleavage regression for the indicated conditions. P value reported is from a χ2 test. Scale bars, 5 µm. (G) Left: Working model for narrowing of NE holes by lateral flow of ER membrane sheets to restrict passage of large macromolecules. Right: Schematic model of defects in nuclear hole closure in different genetic backgrounds investigated in this study.

To test if the ectopic ER sheets caused by increased PI levels in cnep-1Δ mutants (Bahmanyar et al., 2014) are responsible for the observed defects in the NE permeability barrier, we RNAi-depleted cdgs-1 and pisy-1, the genes encoding the enzymes in the pathway of PI production that, when depleted, reduce elevated PI levels and rescue the formation of ectopic ER sheets in cnep-1Δ mutants (Bahmanyar et al., 2014; Fig. 5 A and Fig. S3 E). RNAi depletion of cdgs-1 in cnep-1Δ and cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ double mutants that rescued ectopic ER sheet formation, as observed by differential interfence contrast (DIC) (Fig. 5 D), also prevented the diffusion of 70-kD dextrans into the nuclei of cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ double mutants (Fig. 5, D–F). In addition, depletion of pisy-1 rescued nuclear entry of GFP::α-tubulin in cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ double mutants (Fig. S3 F). Since shifting flux in the phospholipid synthesis pathway toward PI produces ectopic ER sheets (Bahmanyar et al., 2014), these data indicate that the increased PI production and ectopic ER sheets in cnep-1Δ mutants are responsible for the observed defects in NE closure. The experiments with fluorescent dextrans confirmed that holes in the NE rather than transport defects cause the defects in permeability of the NE in cnep-1Δ and cnep-1Δ;chmp-7Δ embryos. We conclude that CNEP-1 regulates lipin to control PI production near the NE and prevent the invasion of ER membranes into NE openings and promote NE closure.

The acentriolar spindle in C. elegans oocyte meiosis provides the unique opportunity to analyze the closure and sealing of a large opening in the NE that coincides with spindle MTs. Using this system and building on previous work in C. elegans embryos (Bahmanyar et al., 2014), we show that CNEP-1 spatially regulates lipin to restrict membrane invasion at NE openings and ensure NE sealing. This provides a mechanism that is sufficient to prevent detectable leakage of proteins across the NE in the absence of NE-specific adaptors for ESCRT-III. We propose a model of nuclear closure in which ER membranes move, potentially along persisting spindle MTs, to sites nearby remaining NE openings (Fig. 5 G) and prevent passage of macromolecules across the NE by lateral flow of lipids to narrow NE openings (Fig. 5 G). CNEP-1 regulates lipin’s phosphatidic acid phosphatase activity to restrict the production of PI-rich membranes near the NE to prevent their overflow into NE openings during NE closure. LEM-2/CHMP-7 remodel excess membranes to prevent severe consequences of membrane invasion to the nuclear permeability barrier (Fig. 5 G).

The fact that restoring ectopic ER membrane sheets present in cnep-1Δ mutant embryos by shifting flux away from PI production (Bahmanyar et al., 2014) also rescues nuclear permeability barrier defects suggests that the defects arise from aberrant ER sheet production. PI is an inverted cone–shaped lipid, so its accumulation may disrupt lipid packing, the association of membrane-shaping proteins, and/or have downstream effects on the production of other lipids in the ER/NE, such as PI derivatives (phosphoinositides). In support of this, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) regulates the recruitment of ESCRTs to the reforming NE (Ventimiglia et al., 2018), and its misregulation may account for the mild delay we observed in the recruitment of ESCRT components in cnep-1 mutants. Future work is required to determine how PI, a relatively low abundant lipid in the ER (van Meer et al., 2008), or flux in the glycerolipid pathway gives rise to defects in ER structure and nuclear closure.

Together our data demonstrate that the CNEP-1–lipin pathway coordinates the production of ER membranes with the feeding of ER membranes into NE openings to promote nuclear closure. This process requires ESCRT-mediated membrane remodeling when membranes are in excess. Our findings emphasize the importance of regulation of glycerolipid flux to form and remodel the NE from ER-derived membranes.

Materials and methods

Strains

Strains were maintained on nematode growth media plates seeded with OP50 Escherichia coli and stored at 20°C. Strains used in this paper are listed in Table S1. The deletion of T24B8.2 (chmp-7) was generated with CRISPR-Cas9 with crRNAs listed in Table S2. To generate the T24B8.2 deletion by CRISPR-Cas9, we injected Cas9-CRISPR RNA (crRNA) trans-activating crRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes that were assembled in vitro into C. elegans gonads (Paix et al., 2015). In brief, crRNAs were annealed with transfer RNAs (trRNAs) at 95°C for 2 min, and the annealed complexes (final concentration: 11.7 μM) were added to Cas9 protein (qb3 Berkeley, final concentration: 14.7 μM), along with dpy-10 crRNAs annealed with trRNA (final concentration: 3.7 µM) and a dpy-10(cn64) repair template (final concentration: 29 ng/ml) as a co-injected CRISPR positive control (Arribere et al., 2014). The mixture was also injected into cnep-1Δ adult worms to generate double mutants. Roller F1 progeny were singled out onto OP50 plates, allowed to lay progeny, and genotyped by PCR to identify a strain with a deletion for T24B8.2. Deletion strains were outcrossed to N2 worms at least 4× after their generation.

RNA interference

Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) used in this study were generated with the oligos listed in Table S3. T3 and/or T7 transcription reactions (MEGAscript, Life Technologies) were run with purified PCR products as templates for 5 h. T3 and T7 reactions were mixed and purified using a phenol-chloroform purification for dsRNAs. For depletion of a gene, the dsRNA was diluted to 1 mg/ml in 1× soaking buffer (Penfield et al., 2018) and spun down in a centrifuge for 30 min at 4°C. dsRNA was loaded into an injecting needle and injected into larval stage 4 (L4) worms. Worms were incubated at 20°C for 24 h (chmp-7, lem-2, lmn-1, and vps-32), 48 h (cdgs-1, pisy-1, and vps-32), or 12 h (lpin-1) before imaging.

Brood size and lethality tests

L4 worms were isolated onto individual OP50-seeded plates and allowed to lay progeny for 24 h. Then, the worms were moved to individual plates and allowed to lay progeny for an additional 24 h and removed from the plates. Embryos were allowed 1 d to hatch before counting the number of hatched and unhatched embryos from each plate. The numbers of embryos were combined over the 48 h for the brood size and embryonic lethality quantification.

Live and fixed microscopy

Adult hermaphrodites were dissected in M9 to release embryos for live microscopy. Embryos were transferred to a 2% agarose slide compressed by a coverslip, and imaged at room temperature (∼21°C). Live and fixed embryos were imaged on an inverted Nikon Ti microscope equipped with a confocal scanner unit (CSU-XI, Yokogawa) with solid state 100-mW 488-nm and 50-mW 561-nm lasers, with a 60 × 1.4 NA plan Apo objective lens, and a high-resolution ORCA R-3 Digital CCD Camera (Hamamatsu). Early embryos for live imaging were imaged at a temporal resolution of 20 s, and five z-slices were acquired with 2-µm steps. For 3D projections (Fig. 1 D and Fig. S1 D), 10–15 z-slices were acquired with 0.5-µm steps.

Dextrans

Fluorescent Dextrans (Texas Red 70,000 MW, Lysine Fixable, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were diluted in 1× soaking buffer to 0.8 mg/ml as previously described (Portier et al., 2007) and injected into gonads of young adults. Injected worms were incubated at 20°C for 5 h before imaging.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (Penfield et al., 2018). Primary antibodies in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween 20 (PBST) were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber (45 µl per slide; mouse α-tubulin [clone DM1A; EMD Millipore], 0.5 µg/ml; goat α-GFP [Hyman laboratory], 1 µg/ml; rabbit α-VPS-32, 0.5 µg/ml; and rabbit-anti-CHMP-7 1 µg/ml). Following primary antibody incubation, slides were washed twice for 10 min in PBST and incubated for 1 h in the dark with secondary antibody in PBST at room temperature (anti-rabbit Cy3/Rhodamine, 1:200; anti-mouse Cy5 1:200; anti-goat FITC 1:200; and anti-rabbit Cy5 1:200). All secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch. Slides were then washed with PBST twice for 10 min in the dark and mounted with Molecular Probes ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI.

Immunoblot

For each condition, 30–35 adult worms were collected and washed two times with M9 (Na2HPO4, 4.2 mM; KH2PO4, 2.2 mM; MgSO4, 1 mM; and NaCL, 8.6 mM in double distilled H2O) and 0.1% Triton X-100 and brought to a volume of 30 µl in microcentrifuge tubes. Then, 10 µl of 4× sample buffer were added to each tube, and tubes were sonicated for 10 min at 70°C. Then, tubes were incubated at 95°C for 5 min followed by an additional 10 min of sonication at 70°C. The samples were frozen at –20°C before running a protein gel. 20 µl of lysate was loaded into each lane and run on an SDS–PAGE gel. An equal amount of worms/lysate volume were loaded between WT (100%) and RNAi-depleted conditions. Samples were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting; primary antibodies were added at a concentration of 1 µg/ml for rabbit-anti-VPS-32, rabbit-anti-CHMP-7, and mouse-anti-α-tubulin (EMD Millipore). Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5,000 for HRP-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit and 1:7,000 for HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Image analysis

Fluorescence intensity measurements were made using ImageJ (Fiji) software (National Institutes of Health), and measurements were analyzed in a systematic manner to minimize bias. All embryos were included for the analysis unless they became arrested/were damaged.

To measure the nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio of GFP::NLS::LacI, the average nuclear and cytoplasmic signals were measured and subtracted for the average camera background for each time point. The nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio was then normalized for nuclear area for each time point.

For line scans, a 5-pixel-wide, 10-µm-long line was drawn across the forming oocyte-derived pronucleus, and each fluorescent intensity value was plotted along a line after subtraction of background (the average of a 5-pixel-wide, 10-µm-long line in the background). To measure the percent of fluorescent intensity of the meiotic spindle (Fig. 1 F), 5-pixel-wide line scans were drawn across the spindle at time 0 and the time of GFP::LEM-2 plaque formation and subtracted for the average camera background. The average maximum values of the time of GFP::LEM-2 plaque formation were divided by the average maximum values of time of maximum spindle shortening.

Transmission electron microscopy

Whole C. elegans animals were mounted on 1-hexadecene–coated Type A aluminum sample holders (100 µm deep) in a paste of OP50 bacteria and frozen using a Balzers HPM 010 high-pressure freezer. The samples were rapidly freeze substituted (∼4 h) in 1% OsO4, 1% H2O in acetone (Müller-Reichert et al., 2007; McDonald, 2014). Animals were infiltrated with increasing concentration of epoxy resin (EMbed 812, EMS) and polymerized at 60°C for 24 h. Samples were then remounted on blank resin blocks for sectioning. Hardened blocks were sectioned using a Leica UltraCut UC7. 60-nm sections were collected on formvar-coated nickel grids and stained using 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. 60-nm grids were viewed FEI Tencai Biotwin TEM at 80 Kv. Images were taken using Morada CCD and iTEM (Olympus) software.

Electron tomography and 3D modeling

Hermaphrodites were dissected in Minimal Edgar’s Growth Medium (Edgar, 1995; Woog et al., 2012), and embryos in meiosis were transferred to cellulose capillary tubes (Leica Microsystems). The embryos were observed with a stereo microscope and placed into membrane carriers at anaphase I or II for immediate cryo-immobilization using an EMPACT2+RTS high-pressure freezer (Leica Microsystems; Redemann et al., 2018). Freeze substitution was performed over 3 d at −90°C in anhydrous acetone containing 1% OsO4 and 0.1% uranyl acetate using an automatic freeze substitution machine (EM AFS, Leica Microsystems). Epon/Araldite infiltrated samples were embedded in a thin layer of resin and polymerized for 3 d at 60°C. Serial semi-thick (300-nm) sections were cut using an Ultracut UCT Microtome (Leica Microsystems), collected on Formvar-coated copper slot grids, and post-stained with 2% uranyl acetate in 70% methanol followed by Reynold’s lead citrate (Müller-Reichert et al., 2007). For dual-axis electron tomography (Mastronarde, 1997), 15-nm colloidal gold particles (Sigma-Aldrich) were attached to both sides of the semi-thick sections. Series of tilted views were recorded using a TECNAI F30 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 300 kV. Images were captured every 1.0° over a ±60° range at a pixel size of 2.3 nm using a Gatan US1000 2K × 2K CCD camera. Using the IMOD software package (Kremer et al., 1996), montages of 2 × 1 were collected and combined for each serial section (Redemann et al., 2018). Tomograms were computed for each tilt axis using the R-weighted back-projection algorithm (Gilbert, 1972). The IMOD software package was also used to segment MTs, the ER, and nuclear membranes (Kremer et al., 1996).

Statistical analysis

All data points are reported in graphs and data analysis Middle and error bar types are noted in figure legends. Statistical analysis was performed on datasets with multiple samples and independent biological repeats. A nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare datasets without a normal distribution, determined by a Shapiro–Wilk test, while a χ2 test was used to compare fraction of embryos with indicated phenotypes between conditions. The type of test used, sample sizes, and P values are reported in figure legends or in text (P < 0.05 defined as significant).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows schematic of the chmp-7 gene and corresponding deletion in mutant strain with validating immunoblots as well as fluorescence and electron micrographs of NE formation. Fig. S2 shows electron micrographs and 3D models of nuclear formation and schematics of the lem-2 and cnep-1 genes with deleted regions of mutant strains highlighted. Fig. S2 further shows fluorescence micrographs from time-lapse imaging of GFP::LEM-2 and the meiotic spindle as well as immunofluorescence of CHMP-7 and VPS-32 in control and cnep-1Δ strains. Fig. S3 shows an immunoblot probing for VPS-32, embryonic lethality and brood size in mutant strains, and experiments that test the regulation of lipid synthesis in NE formation. Video 1 is from Fig. 1 F, Video 2 is from Fig. S1 F, Video 3 is from Fig. S2 A, Video 4 and Video 5 are from Fig. 2 A, Video 6 and Video 7 are from Fig. 2 B, Video 8 is from Fig. 3 A, and Video 9 is from Fig. 4 A. Table S1 lists C. elegans strains used in this study, Table S2 lists the crRNAs for generation of CRISPR-deletion strains, and Table S3 lists the oligonucleotides used in this study.

Supplementary Material

lists C. elegans strains used in this study.

lists the crRNAs for generation of CRISPR-deletion strains.

lists the oligonucleotides used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Gibson for training on IMOD and Xinran Liu and Morven Graham (Yale EM Facility) for assistance with 2D transmission EM of thin sections. We are grateful to Tom Pollard for feedback on the manuscript. We would like to thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for strains utilized in this study.

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER Award to S. Bahmanyar (NSF CAREER 1846010), National Science Foundation award 1661900 to A. Audhya, National Institutes of Health grant R01GM088151 to A. Audhya, and the German Research Foundation (DFG grants MU1423/3-2 and 4-1 to T. Müller-Reichert).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: L. Penfield and S. Bahmanyar conceived the project. L. Penfield performed the majority of the experiments. E. Szentgyörgy and T. Müller-Reichert prepared samples by high-pressure freezing and generated electron tomograms. L. Penfield generated 3D models of reconstructed tomograms. L. Penfield and R. Shankar generated strains used in the manuscript. R. Shankar prepared samples for thin-section transmission EM. A. Laffitte did live imaging of some mitotic embryos, and M. Mauro provided results that guided experiments. L. Penfield and S. Bahmanyar wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors. S. Bahmanyar supervised the project.

References

- Albertson D.G., and Thomson J.N.. 1993. Segregation of holocentric chromosomes at meiosis in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Chromosome Res. 1:15–26. 10.1007/BF00710603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribere J.A., Bell R.T., Fu B.X.H., Artiles K.L., Hartman P.S., and Fire A.Z.. 2014. Efficient marker-free recovery of custom genetic modifications with CRISPR/Cas9 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 198:837–846. 10.1534/genetics.114.169730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S. 2015. Spatial regulation of phospholipid synthesis within the nuclear envelope domain of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nucleus. 6:102–106. 10.1080/19491034.2015.1010942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S., Biggs R., Schuh A.L., Desai A., Müller-Reichert T., Audhya A., Dixon J.E., and Oegema K.. 2014. Spatial control of phospholipid flux restricts endoplasmic reticulum sheet formation to allow nuclear envelope breakdown. Genes Dev. 28:121–126. 10.1101/gad.230599.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann O., and Walz B.. 2001. Endoplasmic reticulum of animal cells and its organization into structural and functional domains. Int. Rev. Cytol. 205:149–214. 10.1016/S0074-7696(01)05004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos W.H., Houben F., Kamps M., Malhas A., Verheyen F., Cox J., Manders E.M.M., Verstraeten V.L.R.M., Van Steensel M.A.M., Marcelis C.L.M., et al. 2011. Repetitive disruptions of the nuclear envelope invoke temporary loss of cellular compartmentalization in laminopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20:4175–4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denais C.M., Gilbert R.M., Isermann P., McGregor A.L., te Lindert M., Weigelin B., Davidson P.M., Friedl P., Wolf K., and Lammerding J.. 2016. Nuclear envelope rupture and repair during cancer cell migration. Science. 352:353–358. 10.1126/science.aad7297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar L.G. 1995. Blastomere culture and analysis. Methods Cell Biol. 48:303–321. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61393-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabritius A.S., Ellefson M.L., and McNally F.J.. 2011. Nuclear and spindle positioning during oocyte meiosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23:78–84. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagone P., and Jackowski S.. 2009. Membrane phospholipid synthesis and endoplasmic reticulum function. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl):S311–S316. 10.1194/jlr.R800049-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P.F. 1972. The reconstruction of a three-dimensional structure from projections and its application to electron microscopy. II. Direct methods. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 182:89–102. 10.1098/rspb.1972.0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A., Liu J., and Cohen-Fix O.. 2009. Inactivation of the C. elegans lipin homolog leads to ER disorganization and to defects in the breakdown and reassembly of the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Sci. 122:1970–1978. 10.1242/jcs.044743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorjánácz M., and Mattaj I.W.. 2009. Lipin is required for efficient breakdown of the nuclear envelope in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 122:1963–1969. 10.1242/jcs.044750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsey N., Han G.S., O’Hara L., Rochford J.J., Carman G.M., and Siniossoglou S.. 2008. Temporal and spatial regulation of the phosphatidate phosphatases lipin 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 283:29166–29174. 10.1074/jbc.M804278200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M., LaJoie D., Chen O.S., von Appen A., Ladinsky M.S., Redd M.J., Nikolova L., Bjorkman P.J., Sundquist W.I., Ullman K.S., et al. 2017. LEM2 recruits CHMP7 for ESCRT-mediated nuclear envelope closure in fission yeast and human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114:E2166–E2175. 10.1073/pnas.1613916114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann C.T., Sears R.M., Katiyar A., Busselman B.W., Aman L.K., Zhang Q., O’Bryan C.S., Angelini T.E., Lele T.P., and Roux K.J.. 2019. Repair of nuclear ruptures requires barrier-to-autointegration factor. J. Cell Biol. 218:2136–2149. 10.1083/jcb.201901116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampoelz B., Mackmull M.T., Machado P., Ronchi P., Bui K.H., Schieber N., Santarella-Mellwig R., Necakov A., Andrés-Pons A., Philippe J.M., et al. 2016. Pre-assembled Nuclear Pores Insert into the Nuclear Envelope during Early Development. Cell. 166:664–678. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G.S., Wu W.I., and Carman G.M.. 2006. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 281:9210–9218. 10.1074/jbc.M600425200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Bahmanyar S., Zhang P., Grishin N., Oegema K., Crooke R., Graham M., Reue K., Dixon J.E., and Goodman J.M.. 2012. Nuclear envelope phosphatase 1-regulatory subunit 1 (formerly TMEM188) is the metazoan Spo7p ortholog and functions in the lipin activation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 287:3123–3137. 10.1074/jbc.M111.324350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M.W. 2010. The nuclear envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000539–a000539. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Gentry M.S., Harris T.E., Wiley S.E., Lawrence J.C. Jr., and Dixon J.E.. 2007. A conserved phosphatase cascade that regulates nuclear membrane biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:6596–6601. 10.1073/pnas.0702099104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J.R., Mastronarde D.N., and McIntosh J.R.. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76. 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova M., Gu Y., Chen J.S., Beckley J.R., Gould K.L., and Oliferenko S.. 2016. Temporal Regulation of Lipin Activity Diverged to Account for Differences in Mitotic Programs. Curr. Biol. 26:237–243. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde D.N. 1997. Dual-axis tomography: an approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 120:343–352. 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough J., Frost A., and Sundquist W.I.. 2018. Structures, Functions, and Dynamics of ESCRT-III/Vps4 Membrane Remodeling and Fission Complexes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 34:85–109. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Reichert T., Srayko M., Hyman A., O’Toole E.T., and McDonald K.. 2007. Correlative light and electron microscopy of early Caenorhabditis elegans embryos in mitosis. Methods Cell Biol. 79:101–119. 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)79004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara L., Han G.S., Peak-Chew S., Grimsey N., Carman G.M., and Siniossoglou S.. 2006. Control of phospholipid synthesis by phosphorylation of the yeast lipin Pah1p/Smp2p Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 281:34537–34548. 10.1074/jbc.M606654200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oegema K., and Hyman A.A.. 2006. Cell division. WormBook. 19:1–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos Y., Hodgson L., Mantell J., Verkade P., and Carlton J.G.. 2015. ESCRT-III controls nuclear envelope reformation. Nature. 522:236–239. 10.1038/nature14503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos Y., Perdrix-Rosell A., and Carlton J.G.. 2016. Membrane Binding by CHMP7 Coordinates ESCRT-III-Dependent Nuclear Envelope Reformation. Curr. Biol. 26:2635–2641. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paix A., Folkmann A., Rasoloson D., and Seydoux G.. 2015. High efficiency, homology-directed genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans using CRISPRCas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Genetics. 201:47–54. 10.1534/genetics.115.179382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield L., Wysolmerski B., Mauro M., Farhadifar R., Martinez M.A., Biggs R., Wu H.Y., Broberg C., Needleman D., and Bahmanyar S.. 2018. Dynein-pulling forces counteract lamin-mediated nuclear stability during nuclear envelope repair. Mol. Biol. Cell. 29:852–868. 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson T.R., Sengupta S.S., Harris T.E., Carmack A.E., Kang S.A., Balderas E., Guertin D.A., Madden K.L., Carpenter A.E., Finck B.N., et al. 2011. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell. 146:408–420. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier N., Audhya A., Maddox P.S., Green R.A., Dammermann A., Desai A., and Oegema K.. 2007. A microtubule-independent role for centrosomes and aurora a in nuclear envelope breakdown. Dev. Cell. 12(4):515–529. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab M., Gentili M., de Belly H., Thiam H.R., Vargas P., Jimenez A.J., Lautenschlaeger F., Voituriez R., Lennon-Duménil A.M., Manel N., et al. 2016. ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death. Science. 352:359–362. 10.1126/science.aad7611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redemann S., Lantzsch I., Lindow N., Prohaska S., Srayko M., and Müller-Reichert T.. 2018. A Switch in Microtubule Orientation during C. elegans Meiosis. Curr. Biol. 28:2991–2997.e2. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Rosa H., Leung J., Grimsey N., Peak-Chew S., and Siniossoglou S.. 2005. The yeast lipin Smp2 couples phospholipid biosynthesis to nuclear membrane growth. EMBO J. 24:1931–1941. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniossoglou S. 2013. Phospholipid metabolism and nuclear function: roles of the lipin family of phosphatidic acid phosphatases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1831:575–581. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tange Y., Hirata A., and Niwa O.. 2002. An evolutionarily conserved fission yeast protein, Ned1, implicated in normal nuclear morphology and chromosome stability, interacts with Dis3, Pim1/RCC1 and an essential nucleoporin. J. Cell Sci. 115:4375–4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungricht R., and Kutay U.. 2017. Mechanisms and functions of nuclear envelope remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18:229–245. 10.1038/nrm.2016.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald K.L. 2014. Rapid embedding methods into epoxy and LR White resins for morphological and immunological analysis of cryofixed biological specimens. Microsc. Microanal. 20(1):152–163. 10.1017/S1431927613013846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G., Voelker D.R., and Feigenson G.W.. 2008. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:112–124. 10.1038/nrm2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas J.D., Hatch E.M., Anderson D.J., and Hetzer M.W.. 2012. Transient nuclear envelope rupturing during interphase in human cancer cells. Nucleus. 3:88–100. 10.4161/nucl.18954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventimiglia L.N., Cuesta-Geijo M.A., Martinelli N., Caballe A., Macheboeuf P., Miguet N., Parnham I.M., Olmos Y., Carlton J.G., Weissenhorn W., et al. 2018. CC2D1B Coordinates ESCRT-III Activity during the Mitotic Reformation of the Nuclear Envelope. Dev. Cell. 47:547–563.e6. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vietri M., Schink K.O., Campsteijn C., Wegner C.S., Schultz S.W., Christ L., Thoresen S.B., Brech A., Raiborg C., and Stenmark H.. 2015. Spastin and ESCRT-III coordinate mitotic spindle disassembly and nuclear envelope sealing. Nature. 522:231–235. 10.1038/nature14408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster B.M., Thaller D.J., Jäger J., Ochmann S.E., Borah S., Lusk C.P., and Webster B.M.. 2016. Chm 7 and Heh 1 collaborate to link nuclear pore complex quality control with nuclear envelope sealing. EMBO J. 35:e201694574 10.15252/embj.201694574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente S.R., and Rout M.P.. 2010. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000562 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert T., and Hurley J.H.. 2010. Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature. 464:864–869. 10.1038/nature08849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woog I., White S., Büchner M., Srayko M., and Müller-Reichert T.. 2012. Correlative light and electron microscopy of intermediate stages of meiotic spindle assembly in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Methods Cell Biol. 111:223–234. 10.1016/B978-0-12-416026-2.00012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.Y., McNally K., and McNally F.J.. 2003. MEI-1/katanin is required for translocation of the meiosis I spindle to the oocyte cortex in C elegans. Dev. Biol. 260:245–259. 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00216-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

lists C. elegans strains used in this study.

lists the crRNAs for generation of CRISPR-deletion strains.

lists the oligonucleotides used in this study.