Abstract

Antibiotics are commonly overused to reduce weaning stress that leads to economic loss in swine production. As potential substitutes of antibiotics, plant extracts have attracted the attention of researchers. However, one of the plant extracts, tannic acid (TA), has an adverse effect on the growth performance, palatability, and intestinal absorption in weaning piglets when used at a large amount. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the effects of a proper dose of microencapsulated TA on the growth performance, organ and intestinal development, intestinal morphology, intestinal nutrient transporters, and colonic microbiota in weaning piglets. Forty-five Duroc × [Landrace × Yorkshire] (initial body weight = 5.99 ± 0.13 kg, weaned days = 21 d) piglets were randomly divided into five treatment groups (n = 9) and raised in 14 d. The piglets in the control group were raised on a basal diet; the piglets in the antibiotic test group were raised on a basal diet with three antibiotics (375 mg/kg Chlortetracycline 20%, 500 mg/kg Enramycin 4%, 1,500 mg/kg Oxytetracycline calcium 20%); and the other three groups were raised on a basal diet with three doses of microencapsulated TA (TA1, 500 mg/kg; TA2, 1,000 mg/kg; TA3, 1,500 mg/kg). All the piglets were raised in the same environment and given the same amount of nutrients for 2 wk. The results showed that both TA1 and TA2 groups had no adverse effect on the growth performance, organ weight and intestinal growth, and the pH value of gastrointestinal content. TA2 treatment improved the duodenal morphology (P < 0.05), increased the gene expression level of solute carrier family 6, member 19 and solute carrier family 15, member 1 (P < 0.05) in the ileum, and modulated the colonic bacteria composition (P < 0.05), but inhibited the activity of maltase in the ileum (P < 0.05) and the jejunal gene expression level of solute carrier family 5, member 1 (P < 0.05). In conclusion, our study suggests that a dosage between 500 and 1,000 mg/kg of microencapsulated TA is safe to be included in the swine diet and that 1,000 mg/kg of microencapsulated TA has beneficial effects on intestinal morphology, intestinal nutrient transporter, and intestinal microbiota in weaning piglets. These findings provide new insights into suitable alternatives to antibiotics for improving growth performance and colonic microbiota.

Keywords: colonic microbiota, growth performance, intestinal morphology, microencapsulated tannic acid, weaning piglets

Introduction

Weaning is a necessary stage in pig husbandry. Weaning piglets are exposed to multiple stresses, such as social, environmental, and dietary stress. These stresses lead to reducing production performance, digestion, and intestinal absorption of piglets (Pluske et al., 1997; Lallès et al., 2007). Therefore, a variety of antibiotics and chemical growth promoters are used in the modern swine industry to improve animal production. Overuse of antibiotics is closely related to the risk of antimicrobial resistance and raises concern about both animal and human health (Gresse et al., 2017). Due to this concern, many countries in the world have gradually reduced the utilization of antibiotics and chemical growth promoters in livestock production. Moreover, husbandry management and nutritional improvement are the dominating strategies for reducing weaning stress in swine production (Modina et al., 2019). Adding plant extracts in feed can alleviate the weaning stress of piglets (Lee et al., 2009). Thus, there has been a great effort in searching plant extracts as antibiotic alternatives to improve piglet health and secure public health.

Plant extracts have been used to replace antibiotics in swine diets (Windisch et al., 2008). Tannic acid (TA), one of the plant extracts, has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiviral characteristics (Chung et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2019). However, many years ago, tannins were considered as anti-nutritional feed additive for monogastric animals, because they bind to proteins, starches, minerals, and digestive enzymes to reduce the absorption of nutrients (Chung et al., 1998). Recently, several studies have shown that feed supplemented with low concentrations of tannin promotes animal health and improve nutrition status and animal growth performance, such as weaned piglets, growing pigs, and broiler chicken (Biagia et al., 2010; Brus et al., 2013; Starčević et al., 2015). Current research shows problems related to dietary supplemented tannin in animals, such as poor palatability; therefore, it has been limited as a feed additive in swine diet (Huang et al., 2018).

Microencapsulation (size 1 µm to 7 mm) is the method of packaging material into a miniature called capsule, including liquid and solid substance (Azagheswari et al., 2015). Microencapsulation is extensively applied to the field of food, medicine, and agriculture due to many functions, such as reducing the gastric irritation, increasing the stability of substance, protecting the environment, masking the poor taste and odor, and altering the absorbed site (Bansode et al., 2010). These studies indicate that microencapsulation is the potential scheme to improve the palatability in swine diet. Tannins are extracted from many plant sources, such as chestnut, Turkish gallnut, Chinese gallnut, Korean maple, and hazel (Chung et al., 1998). Hydrolyzed tannins sourced from chestnut and gallnut are commonly used as a feed additive for monogastric animals, but a large amount of hydrolyzed tannins, whatever the source, reduce the growth performance by anti-nutritional effect (Huang et al., 2018). Some studies of TA have been researched in monogastric animals, for example, dietary supplementation of 0.5% TA increased growth performance and thoracic fat content but decreased the blood glucose level and hepatic cholesterol content in broiler chicken (Starčcević et al., 2015). In addition, Lee et al. (2009) showed that 0.0125% TA in diet had no negative effect on the growth performance of weaning piglets. However, Lee et al. (2010) reported that 0.0125% to 0.1% TA in diet negatively affected the growth performance of weaning pigs. However, TA (extracted from Chinese gallnut) for swine production is limited and TA has potentials as feed additive to replace the antibiotics (Huang et al., 2018). Moreover, Chinese gallnut (containing over 70% TA) has been used as traditional Chinese medicine for a long time and widely distributed in China (Min and Longton, 1993). Therefore, our current study aimed to investigate the effects of proper dose of microencapsulated TA (extracted from Chinese gallnut) as a substitute to antibiotics on the growth performance, intestinal parameters, intestinal morphology, the activities of intestinal digestive enzyme, the mRNA expression of nutrient carriers, and the colonic microbiota.

Material and Methods

The experimental programming and process for the current study were permitted and supervised by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Hunan Normal University, Changsha City, Hunan, China (2019-1A).

Animals and experiment design

Forty-five piglets (Duroc × [Landrace × Yorkshire]; initial body weight [BW] = 5.99 ± 0.13 kg; half male and half female) were weaned at the age of 21 d and randomly divided into five treatment groups with nine piglets per group: 1) control group (CON)—piglets were raised on a basal diet; 2) antibiotic test group (AB)—piglets were raised on a basal diet supplemented with 375 mg/kg Chlortetracycline (20%), 500 mg/kg Enramycin (4%), and 1,500 mg/kg Oxytetracycline calcium (20%); 3) TA1—piglets were raised on a basal feed added with 500 mg/kg microencapsulated TA; 4) TA2—piglets were raised on a basal feed added with 1,000 mg/kg microencapsulated TA; and 5) TA3—piglets were raised on a basal diet added with 1,500 mg/kg microencapsulated TA. The basal feed met the nutrient demand of the NRC (2012) and their diet composition is shown in Supplementary Table S1. TA was extracted from Chinese gallnut by the Wufeng Chicheng Biotechnology Company Limited, Yichang, China. The technology for the production of microencapsulated TA (30% effective concentrations) was provided by the Kangjude Company Limited, Hangzhou, China. The dosage for TA supplementation was selected according to the study by Lee et al. (2010). There were nine pens per treatment group and one pig per pen. Each piglet was fed in an indoor environment with a space (0.5 × 1 m) for movement. Piglets were housed in a cleanly plastic slatted flooring, the environmental temperature was maintained at 25 ± 2 °C, and the average humidity was managed at 65% ± 5% in the whole trial period. All weaning pigs had ad libitum access to feed and water during a period of the experiment. Growth performance was measured based on average daily growth (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed conversion rate (FCR). BW was measured weekly and feed intake was calculated everyday. The calculated method of ADG = (final BW − initial BW)/experimental days. The calculated formula of ADFI = total feed intake/experimental days. The calculated formula of FCR = total feed intake/total weight gain. Based on the growth performance of the weaning piglets, we chose the group of TA2 to investigate the intestinal enzyme, intestinal morphology, gene expression, and colonic microbiota.

Sample collection

After 14 d of treatment and an overnight fasting, the BW of the piglets was determined for blood and tissue sampling according to the process described by Yang et al. (2016). The piglets were given general anesthesia and injected with a 4% sodium pentobarbital solution (40 mg/kg BW) to kill. Then, the small intestine (SI) and large intestine (LI) were taken out and the length was measured by fixing it vertically against a ruler. The weight of the SI and LI was determined after the removal of content and mesenterium. The weight of the heart, liver, spleen, and kidneys was measured. Relative organ weight can be calculated as the measured organ weight diving by the final BW. Segments of the duodenum (30 cm after the stomach), jejunum (5 m before the ileal-cecal junction), and ileum (30 cm before the ileal-cecal junction) were rinsed several times with physiological saline. These intestinal segments were divided into two segments. One segment (about 2 cm) were fixed in 4% formaldehyde-phosphate buffer to analyze intestinal morphology, and the remaining segments were used for collecting the intestinal mucosa. The mucosal cell layers were scraped off using microslides and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. These mucosal tissue samples were stored at ultra-low temperature freezer until they were required for exploring gene expression and measuring enzyme activity (Zong et al., 2018). Moreover, we have collected the colonic content in a 1.5-mL sterile centrifuge tube (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for determining the colonic microbiota. The content from the stomach, ileum, cecum, and colon was collected in a 50-mL self-standing bottomed centrifuge tube (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and the pH value was detected by the checker pH tester (INESA scientific instrument CO., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

Intestinal morphology

The intestinal morphology was measured as the previous study did (Zong et al., 2018). Briefly, the intestinal segments were dehydrated in a gradient ethanol and embedded in paraffin wax. Each embedded sample was cut into three sections (5 µm in thickness) by microtome (RM2235; Leica, Germany) and then placed on the microslides. The microslides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Villus height (defined as the peak of the villi to the villus crypt joint) and crypt depth (defined as the depth of emboly between close villi) of each sample were measured using 10× magnification of a microscope (Leica Imaging Systems Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Each piglet’s villus height and crypt depth were calculated from 30 unbroken villi and their corresponding crypts.

Intestinal enzyme

Tissue samples were homogenized and extracted according to the process described in the study of Zong et al. (2018). The enzymatic activities of intestinal alkaline phosphatase (ALP), lactase, sucrase, and maltase were determined using commercially available kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Gene expression analysis by real-time PCR

The expression of gene was analyzed by real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) according to our previous study (Wang et al., 2019). Briefly, total RNA of jejunum and ileum was extracted using TRIZOL reagents (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) and then reverse-transcripted using a complementary DNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Primers were projected on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) online website (Supplementary Table S2). The β-actin was calculated to standardize the target gene expression. Each sample was conducted real-time PCR reaction with triplicate times. All gene expression were calculated through the formula of 2−(ΔΔCt). Normalization of all gene expression was compared as the fold change relative to the CON group.

Bacteria 16s rDNA sequencing and bioinformatics

The bacteria 16s rDNA sequencing was analyzed according to our previous study (Chen et al., 2019). Briefly, the DNA of the colonic contents was extracted using the DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany). The DNA sample from the colonic content and the amplification products were detected using agarose gel electrophoresis. Illumina MiSeq Sequencer was used for the V3 to V4 regions of bacterial 16S rDNA sequencing. Illumina MiSeq sequencing, sequencing data processing, and bioinformatics analysis were produced by the Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Briefly, raw data were sequenced by the Ion S5TM XL platform. High-quality clean reads were obtained by filtering the adapters and low-quality reads (such as trailing quality score < 20, reads with primer mismatches > 2) according to the quality-controlled process. Operational taxonomic unit (OTU, sequence similarity of 97%) clustering and species taxonomy were analyzed by Uparse software. Based on OTU clustering results, we obtained the information of relevant species and the condition of species abundance. The statistical results of Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect size (LEfSe) were operated by the linear discriminant analysis to assess species with significant difference. The function prediction were performed by the database of Tax4Fun. The environmental factor correlation analysis was performed by R software (psych and pheatmap package) in the platform of Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd.

Statistical analysis

The data in the present study were indicated as means ± SEM and were explored the significant difference using the 22nd version of SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) through one-way ANOVA. The differences among various groups were examined with Duncan’s range test. Spearman correlations analysis was used to determine the association between environmental factors and colonic microbiota. Statistical differences of the colonic bacterial community in the phylum, class, order, family, and genus were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis test. Tables and figures in the current study were prepared using the Word 2016 software (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) and Graphpad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, lnc., La Jolla, CA), respectively. P-values < 0.05 were called statistically significant, while 0.05 ≤ P-values < 0.10 were termed as the trend for statistically significant.

Results

Growth performance and organ index

No remarkable differences were observed in BW, ADG, ADFI, and FCR among the five dietary groups (Table 1). The result showed no significant differences in relative organ weight among the treatment groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on growth performance of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA1 | TA2 | TA3 | P-value |

| BW, kg | ||||||

| Initial | 6.00 ± 0.28 | 5.98 ± 0.32 | 5.99 ± 0.29 | 5.98 ± 0.27 | 5.99 ± 0.28 | 1.00 |

| Final | 8.12 ± 0.45 | 8.14 ± 0.48 | 7.88 ± 0.38 | 8.17 ± 0.40 | 7.98 ± 0.36 | 0.98 |

| ADFI, g/d | ||||||

| Day 0 to 7 | 185.35 ± 13.60 | 208.28 ± 20.38 | 171.13 ±18.38 | 202.30 ± 12.01 | 183.49 ± 11.11 | 0.45 |

| Day 8 to 14 | 501.91 ± 36.37 | 539.04 ± 55.02 | 467.55 ± 40.10 | 489.32 ± 31.53 | 467.23 ± 35.84 | 0.72 |

| Day 0 to 14 | 331.46 ± 23.19 | 360.94 ±3 6.22 | 307.94 ± 24.54 | 334.77 ± 19.73 | 314.45 ± 21.60 | 0.64 |

| ADG, kg/d | ||||||

| Day 0 to 7 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.51 |

| Day 8 to 14 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Day 0 to 14 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.92 |

| FCR, g/g | ||||||

| Day 0 to 7 | 2.51 ± 0.43 | 3.20 ± 1.09 | 3.04 ± 0.87 | 2.74 ± 0.41 | 3.10 ± 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Day 8 to 14 | 1.85 ± 0.06 | 1.77 ± 0.13 | 1.89 ± 0.08 | 2.02 ± 0.14 | 1.84 ± 0.10 | 0.54 |

| Day 0 to 14 | 1.93 ± 0.10 | 1.97 ± 0.17 | 2.06 ± 0.15 | 1.95 ± 0.14 | 1.98 ± 0.12 | 0.97 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

Table 2.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on relative organ weight of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA1 | TA2 | TA3 | P-value |

| Liver/BW, g/kg | 25.66 ± 0.58 | 26.42 ± 1.13 | 26.56 ± 0.53 | 23.90 ± 0.90 | 25.68 ± 0.71 | 0.15 |

| Spleen/BW, g/kg | 2.11 ± 0.16 | 2.11 ± 0.20 | 2.15 ± 0.06 | 2.11 ± 0.09 | 2.32 ± 0.14 | 0.84 |

| Kidney/BW, g/kg | 6.24 ± 0.18 | 6.57 ± 0.24 | 6.50 ± 0.18 | 6.06 ± 0.26 | 6.48 ± 0.28 | 0.50 |

| Heart/BW, g/kg | 5.52 ± 0.14 | 5.69 ± 0.17 | 5.80 ± 0.17 | 5.45 ± 0.14 | 5.45 ± 0.13 | 0.38 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

Intestinal growth parameters and gastrointestinal content pH

As shown in Table 3, compared with the AB group, different doses of TA supplementation markedly decreased the ratio of LI weight to BW (P < 0.01), but supplementation with TA had no significant difference relative to the CON group. Next, we analyzed the gastrointestinal content pH in this study. Compared with the CON group and AB group, different doses of TA supplementation had no effect on the pH value of gastrointestinal content in ileum, colon, cecum, and stomach (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on intestinal growth parameters of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA1 | TA2 | TA3 | P-value |

| SI length/BW, cm/kg | 117.24 ± 4.77 | 125.37 ± 5.06 | 118.83 ± 5.26 | 118.23 ± 4.74 | 118.46 ± 4.25 | 0.78 |

| SI weight/BW, g/kg | 49.92 ± 1.74 | 47.13 ± 1.20 | 44.26 ± 2.62 | 45.22 ± 0.94 | 44.58 ± 1.47 | 0.09 |

| LI length/BW, cm/kg | 20.92 ± 1.02 | 21.47 ± 0.55 | 21.98 ± 1.06 | 20.56 ± 1.31 | 21.72 ± 1.39 | 0.90 |

| LI weight/BW, g/kg | 17.36 ± 0.56ab | 19.04 ± 0.78a | 17.04 ± 0.79b | 15.63 ± 0.50b | 16.20 ± 0.57b | <0.01 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

a,bValues in the same row not sharing a common superscript differ significantly.

Table 4.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on gastrointestinal content pH of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA1 | TA2 | TA3 | P-value |

| Stomach pH | 3.53 ± 0.33 | 2.96 ± 0.36 | 4.21 ± 0.49 | 3.12 ± 0.31 | 4.09 ± 0.62 | 0.19 |

| Ileum pH | 7.47 ± 0.06 | 7.49 ± 0.09 | 7.27 ± 0.16 | 7.50 ± 0.07 | 7.55 ± 0.09 | 0.35 |

| Cecum pH | 6.04 ± 0.09 | 6.17 ± 0.05 | 6.08 ± 0.05 | 6.25 ± 0.14 | 6.09 ± 0.14 | 0.57 |

| Colon pH | 6.59 ± 0.10 | 6.67 ± 0.09 | 6.47 ± 0.12 | 6.67 ± 0.10 | 6.61 ± 0.12 | 0.68 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

Intestinal morphology

The intestinal morphology was observed by measuring the crypt depth, villus height, and the ratio of villus height to crypt depth (Table 5). Compared with the CON group, the TA2 group and the AB group had a lower duodenal crypt depth (P < 0.05) and a higher ratio of villus height to crypt depth in the duodenum (P < 0.01), and there were the same results of duodenal morphology between TA2 and AB groups. These results in the table showed that the AB group tended to elevate the ratio of villus height to crypt depth in the jejunum (P < 0.10) compared with CON and TA2 groups. However, no remarkable difference in the crypt depth was found in the colon and cecum among the three dietary treatments (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 5.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on the intestinal morphology of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA2 | P-value |

| Villus Height, µm | ||||

| Duodenum | 246.42 ± 22.13 | 289.92 ± 12.62 | 264.93 ± 8.83 | 0.10 |

| Jejunum | 362.07 ± 12.25 | 377.43 ± 21.42 | 388.37 ± 12.77 | 0.58 |

| Ileum | 277.73 ± 9.16 | 289.99 ± 11.17 | 289.53 ± 19.13 | 0.78 |

| Crypt depth, µm | ||||

| Duodenum | 376.19 ± 4.29a | 300.08 ± 19.47b | 321.27± 13.37b | 0.02 |

| Jejunum | 228.65 ± 7.48 | 217.40 ± 4.56 | 231.22 ± 13.63 | 0.58 |

| Ileum | 221.66 ± 9.66 | 224.68 ± 9.50 | 233.35 ± 9.95 | 0.67 |

| Ratio of villus height: crypt depth, µm: µm | ||||

| Duodenum | 0.68 ± 0.06b | 1.02 ± 0.04a | 0.86 ± 0.03a | <0.01 |

| Jejunum | 1.66 ± 0.06 | 1.91 ± 0.01 | 1.75 ± 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Ileum | 1.37 ± 0.08 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 0.75 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

a,bValues in the same row not sharing a common superscript differ significantly.

Intestinal enzyme activities

As shown in Table 6, the activity of ileal maltase was significantly decreased in the TA2 group than the CON group, but there was the same situation between the TA2 group and the AB group (P < 0.05). The enzyme activities of ALP, lactase, and sucrase in jejunum and ileum were not changed among the three groups.

Table 6.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on digestive enzyme activities of weaned piglets1

| Dietary treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CON | AB | TA2 | P-value |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/mg of protein | ||||

| Jejunum | 136.27 ± 24.93 | 205.97 ± 35.98 | 186.49 ± 32.46 | 0.31 |

| Ileum | 281.79 ± 55.00 | 286.31 ± 56.20 | 289.60 ± 41.84 | 0.99 |

| Maltase, U/mg of protein | ||||

| Jejunum | 173.21 ± 24.73 | 183.56 ± 27.31 | 219.51 ± 33.81 | 0.50 |

| Ileum | 177.14 ± 35.25a | 75.18 ± 10.64b | 107.89 ± 15.81b | 0.03 |

| Lactase, U/mg of protein | ||||

| Jejunum | 21.39 ± 4.05 | 24.20 ± 5.05 | 25.78 ± 3.23 | 0.76 |

| Ileum | 7.31 ± 1.59 | 3.41 ± 1.66 | 5.50 ± 1.61 | 0.25 |

| Sucrase, U/mg of protein | ||||

| Jejunum | 42.14 ± 7.52 | 41.76 ± 12.29 | 43.26 ± 8.31 | 0.99 |

| Ileum | 27.66 ± 8.56 | 34.17 ± 6.91 | 18.2928 ± 6.20 | 0.38 |

1Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 9.

a,bValues in the same row not sharing a common superscript differ significantly.

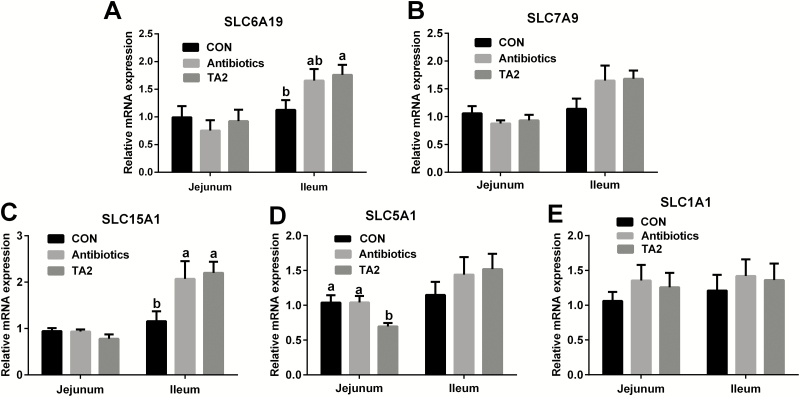

The expression of intestinal nutrient transporter genes

As shown in Figure 1, the mRNA expression of solute carrier family 15, member 1 (SLC15A1) and solute carrier family 6, member 19 (SLC6A19) of ileum were higher in the TA2 group than the CON group (P < 0.05). Compared with the CON and AB groups, dietary TA2 supplementation significantly decreased the mRNA expression of jejunal solute carrier family 5, member 1 (SLC5A1) (P < 0.05). However, no difference was observed in the jejunal and ileal mRNA expression of solute carrier family 7, member 9 (SLC7A9) and solute carrier family 1, member 1 (SLC1A1).

Figure 1.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on the expression of nutrient transporter genes in weaning piglets. The expression of SLC6A19 (A), SLC7A9 (B), SLC15A1 (C), SLC5A1 (D), and SLC1A1 (E) was measured by RT-PCR. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 9. a,bMeans of the bars with different letters are significantly different among groups (P < 0.05).

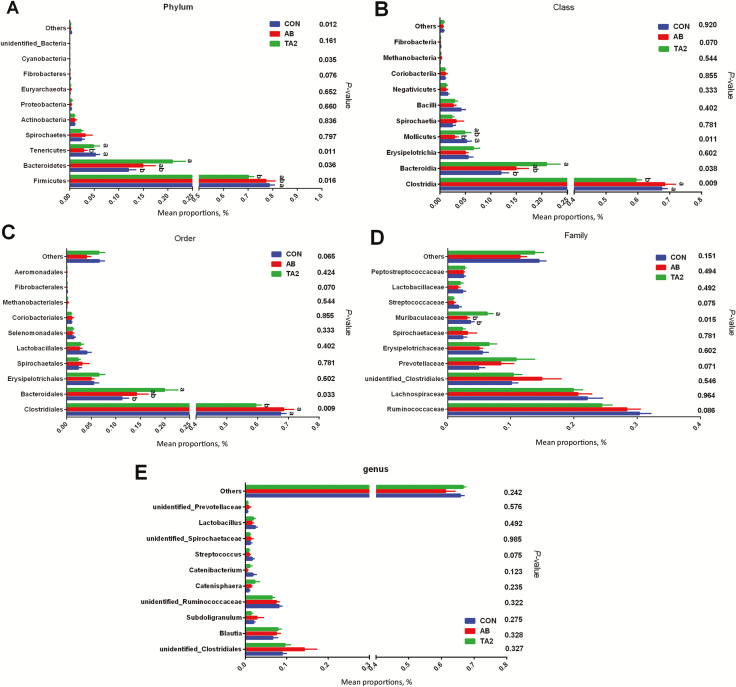

Colonic bacterial community structure

As shown in Figure 2, the dominant microorganisms at the phylum level were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Tenericutes, and Spirochetes, and the dominant class in the bacterial communities were Clostridia, Bacteroidia, Erysipelotrichia, and Mollicutes. At the order level, the dominant microorganisms in each group were Clostridiales, Bacteroidales, and Erysipelotrichia. The relative abundances of Firmicutes at the phylum level, Clostridia at the class level, and Clostridiales at the order level were decreased in the TA2 group when compared with the CON and AB groups (P < 0.05). The relative abundances of Bacteroidetes at the phylum level, Bacteroidia at the class level, and Bacteroidales at the order level were all elevated in the TA2 group when compared with the CON and AB groups (P < 0.05). The relative abundances of Clostridia (class level) and Clostridiales (order level) were highest in the AB group. Dietary supplementation with AB had the lowest abundances of Tenericutes at the phylum level, Mollicutes at the class level, and Muribaculaceae at the family level. Compared with TA and CON groups, the AB group has no significant difference in the relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes at the phylum level, the relative abundances of Bacteroidia at class level, and the relative abundances of Bacteroidales at the order level.

Figure 2.

Effects of dietary supplementation with TA on the colonic bacterial community structure and relative abundance with statistical difference of weaning piglets. In the phylum level, relative abundance with statistical difference among the three groups (A). In the class level, relative abundance with statistical difference among the three groups (B). In the order level, relative abundance with statistical difference among three groups (C). In the family level, relative abundance with statistical difference among three groups (D). In the genus level, relative abundance with statistical difference among three groups (E). a,bMeans of the bars with different letters are significantly different among groups (P < 0.05).

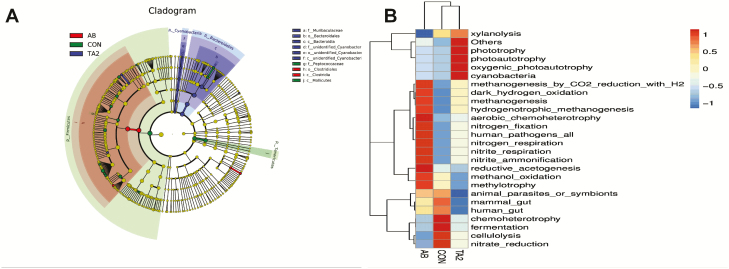

To further discover the taxonomic difference during the experiment, we used LEfSe analysis to find the differential abundance of bacterial taxa (Figure 3A). Ten bacterial biomarkers were identified among the three treatments. Muribaculaceae, Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidia, and other three unidentified microbes were the remarkable microbes in the TA2 group; Peptococcaceae and Mollicutes were the remarkable microbes in the CON group; Clostridiales and Clostridia were the remarkable microbes in the AB group. At the same time, function prediction disclosed that the TA2 group changed the microbial function, such as increasing phototrophy, photoautotrophy, and decreasing animal parasites or symbionts. The CON group was predicted to upregulate the function of fermentation and chemoheterotrophy and downregulate the function of nitrogen fixation and nitrite-ammonification. Dietary AB changed the predicted function of positively regulating nitrogen-fixation, nitrogen-respiration, and so on; moreover, AB group was predicted to negatively regulate xylanolysis, fermentation, chemoheterotrophy, and so on (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

LEfSe analysis for the enriched microbiota (A) and function prediction of colonic microbiota (B).

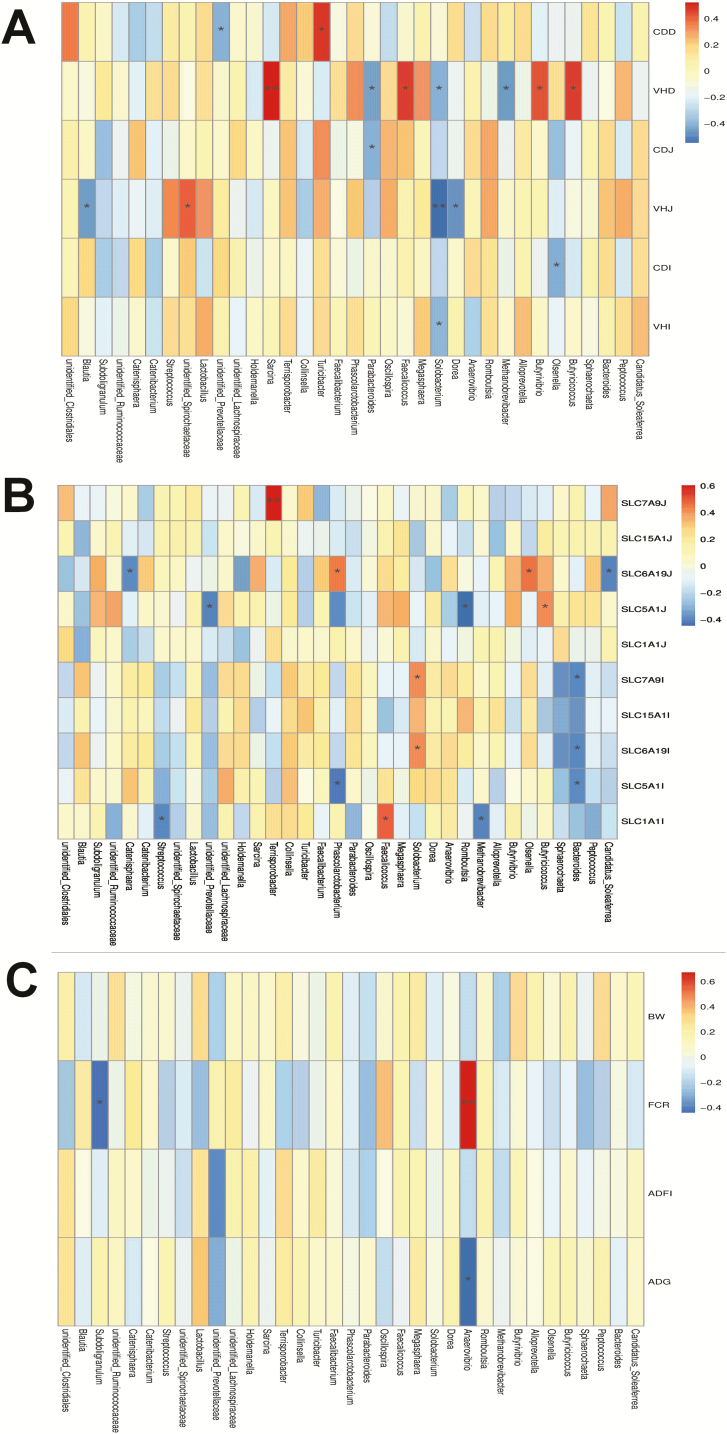

Relationships between bacterial community composition, growth performance, nutrients transporters, and intestinal morphology

Environmental factor correlation analysis revealed that different microbes at the genus level regulated different indices. As shown in Figure 4A, Butyricicoccus, Butyrivibrio, Faecalicoccus, and Sarcina were positively associated with the villus height of duodenum, but Solobacterium was negatively associated with the villus height of the SI. The relative abundance of Terrisporobacter was positively correlated with jejunal transporter of SLC7A9, but the abundance of Bacteroides was negatively correlated with transporter (SLC7A9, SLC6A9, and SLC15A1) of the ileum (Figure 4B). The abundance of Anaerovibrio was positively related to the FCR and negatively related to the ADG; meanwhile, the FCR was negatively correlated to Subdoligranulum (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Environmental factors correlation analysis between the dominant population in the genus level and the intestinal morphology (A), nutrients transporters (B), and growth performance (C). In this figure part (A), VHD, VHJ, and VHI means the villus height of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, respectively; CDD, CDJ, and CDI means the crypt depth of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, respectively; In this figure part (B), SLC7A9J, SLC15A1J, SLC6A19J, SLC5A1J, and SLC1A1J means the SLC7A9, SLC15A1, SLC6A19, SLC5A1, and SLC1A1 of jejunum, respectively; SLC7A9I, SLC15A1I, SLC6A19I, SLC5A1I, and SLC1A1I means the SLC7A9, SLC15A1, SLC6A19, SLC5A1, and SLC1A1 of ileum, respectively.*0.01 < P ≤ 0.05, **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

At present, a low concentration of TA has been extensively described to have no adverse effect on animal growth performance. Indeed, Lee et al. (2009) and our previous results reported that dietary inclusion of TA had no negative effect on the growth performance of weaning piglets and mice (Wang et al., 2019). Meanwhile, TA may have beneficial effects on the gastrointestinal tract of rats if its effective amount in the diet does not exceed 1.5% (Barszcz et al., 2011). Zhao et al. (2019) showed that 0.1% tannins and 0.1% cellulase in the dietary improved the growth performance and carcass characteristics of Hu sheep. It is also reported that dietary supplementation of TA extract (0.5 g/kg) alone and combined with the probiotic B. coagulans increased FCR in coccidiosis-vaccinated broiler chicken (Tonda et al., 2018). However, the TA is generally extracted from chestnut in majority (Biagia et al., 2010; Brus et al., 2013), and few studies explored the Chinese gallnut as the feed additive in piglets research. In our study, just as shown in other research, the dose of microencapsulated TA (extracted from Chinese gallnut) in the diet did not have any negative effect on growth performance in weaning piglets (Lee et al., 2009). Moreover, TA in the diet had no adverse effect on organ development and the pH value of the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, our study showed that the dose (500 to 1,500 mg/kg microencapsulated TA) of Chinese gallnut extracts was a safe dose in weaning piglets. In addition, the poor palatability of TA reduced ADFI when it was supplemented in the animal diet (Huang et al., 2018). Ebrahim et al. (2015) showed that 1% TA in the diet of broiler chicken decreased the feed intake; the TA was directly supplemented in the diet as commercial tannin. Lee et al. (2010) reported that 125 to 1,000mg/kg TA in diet linearly reduced the feed efficiency from 0 to 14 d in weaning piglets; the TA was added in the form of albumin tannate (containing 500g TA/kg) in the diet; therefore, the real dose of TA in the study was 62.5 to 500 mg/kg. In our study, the concentration of TA is 500 to 1,500 mg/kg in weaning piglets but the actual concentration is 150 to 500 mg/kg after microencapsulation; the identically highest concentration of TA in our study did not reduce the ADFI when the result was compared with the research of Lee et al. (2010). The difference between our study and Lee et al.’s study is just the additional form of TA. Moreover, microencapsulated Enterococcus faecalis CG1. 0007 in the diet improved the growth performance of broiler chicken (Han et al., 2013). Combined with the function of microencapsulation, for example, masking the poor taste and odor, increasing the stability of substance (Bansode et al., 2010), suggesting that TA could be modulated poor palatability through the way of microencapsulation in the diet of weaning piglets. However, the microencapsulated TA group and AB group did not improve the growth performance of weaning piglets than the CON group in this study, we speculated that the short experimental days is an important factor to affect the growth performance. Further study should prolong the experimental days after weaning to investigate whether microencapsulated TA could improve the growth performance.

Intestinal weight and length can indicate the effect of diet on intestinal development (Mansbach and Gorelick, 2007). It is observed that a large amount of TA in humans and animals diet can cause anti-nutrition effect (Butler, 1992; Chung et al., 1998). However, Barszcz et al. (2018) revealed that TA (0.25% to 2%) in the diet increased the weight of cecum in rats after 3 wk of feeding. Moreover, our previous study has indicated that the dose of 2.5 to 10 mg/kg TA enhanced the length of the colon in mice (Wang et al., 2019). In this study, this result did not show any negative effect of TA on intestinal development; in addition, the TA group has the consistent influence with the CON group, suggesting that the amount of microencapsulated TA (500 to 1,000 mg/kg) in the swine dietary had no destructive role in intestinal development due to anti-nutritional effect. At the same time, our results elucidated that the treatment of 1,000 mg/kg TA had the same influence with the CON and AB groups, in terms of the parameters such as growth performance, organ index, and intestinal growth features, although the treatment of TA (500 and 1,500 mg/kg) has the tendency to decrease the ratio of SI to BW. Thus, we supposed that the approximate range of 1,000 mg/kg microencapsulated TA (extracted by Chinese gallnut) is the moderate dose as a feed additive in weaning piglets. Furthermore, we selected the 1,000 mg/kg TA group to analyze the intestinal morphology, digestive enzymes activity, intestinal nutrients transporter carrier, and microorganism diversity as a further research in this study.

Intestinal morphology is destroyed after weaning in piglets, which happens in the form of reducing villus height and increasing crypt depth, and then decreasing the absorptive rate of piglets (Yang et al., 2013). A previous report has shown that a high concentration of TA have negative effect on intestine morphology by damaging the gut villi in broilers (Mannelli et al., 2019). However, other reports showed that TA modulates the intestine morphology by increasing the duodenal, jejunal, and ileal villus height of Hu sheep and increasing the villus height, villus perimeter, and mucus thickness of the duodenum in male pigs (Bilić-Šobot et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019). In the present study, TA treatment caused a lower crypt depth and a higher ratio of villus height to crypt depth in the duodenum than in the control group, indicating that TA could meliorate the duodenal damage from weaning stress. In addition, a large amount of TA inhibits the intestinal digestion and absorption by lowering digestive enzyme activities in animals (such as male pigs and rats) (Mueller-Harvey, 2006; Bilić-Šobot et al., 2016). ALP, lactase, and sucrase are leading brush border proteins to exhibit maturation of enterocytes and exert functional capacity in pigs (Tang et al., 1999). We found that TA in the diet had no adverse effect on brush border proteins, despite a decrease in maltase, indicating that the dose of TA (extracted from Chinese gallnut) in our study did not harm digestive enzymes. Intestinal absorption relies on the transporters of nutrients in the epithelium of SI. Our results indicated that TA had the upregulated gene expression of SLC6A19 and SLC15A1 in the ileum and the downregulated gene expression of SLC5A1. Previous study showed that SLC6A19 and SLC15A1 are the important transporters and they are expressed abundantly in the ileum, SLC6A19 is the transporter of glutamine and neutral amino acid, and SLC15A1 is the carrier of many nutrients, such as dipeptides, tripeptides, and carnosine (Stevens, 2010). SLC5A1 is the glucose–galactose carrier (Vallaeys et al., 2013). Our present results show that TA enhanced the protein-absorption capacity of ileum by increasing the gene expression of transporting amino acid and peptides. Previous result explained that the activity of maltase and the mRNA expression level of SLC5A1 had decreased in the TA group. Further experiments should be carried out to examine the content of glucose in serum to identify the effect of TA on glucose of weaning piglets.

Many studies have shown that intestinal bacterial colonization has a crucial role in intestinal absorption and digestion (such as influencing the nutrition availability), intestinal immune regulation (such as regulating immune homeostasis), and intestinal health of the host (such as the beneficial bacteria protect us from dysbiosis-related diseases) (Round and Mazmanian, 2009; Flint et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2017). Some studies have shown that tannins have the antimicrobial property in livestock production. It has been shown that 1% chestnut–tannin extract in the diet reduced postweaning diarrhea by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli F4 infectious model in piglets (Girard et al., 2018). Tretola et al. (2019) reported that the part of hydrolyzable tannins is the reason to affect the quality and quantity of microbiota in the boar diet of both the addition of hydrolyzable tannins and polyunsaturated fatty acid. In addition, two major phyla of gram-negative Bacteroidetes and gram-positive Firmicutes are seen in the normal human and animal gut (Eckburg et al., 2005; Jandhyala et al., 2015), and a high ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes is a possible indicator of obesity (Indiani et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019); the changed ratio of intestinal microbiota might affect normal dietary digestion process (Connolly et al., 2010). Obesity, as a potential factor in metabolic diseases, has been regarded as an imbalance of energy intake and energy output (Hill et al., 2012). Polyphenols (such as tannin) against Firmicutes is stronger than against Bacteroidetes; eating the food containing high polyphenols can reduce BW in obese people (Smith and Mackie, 2004, Rastmanesh, 2011); and dietary polyphenols and their secondary metabolites contribute to the maintenance of intestinal health by regulating the human gut bacterial composition (Hervert-Hernández and Goñi, 2011). Moreover, Hohenshell et al. (2000) have reported that the weight increase in piglets is mainly lean tissue. Our findings clarified that TA group had the lower Firmicutes and the higher Bacteroidetes count than in the CON group on the phylum level, which is consistent with previous findings of decreasing the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in dietary polyphenols treatment (Roopchand et al., 2015; Kawabata et al., 2019), suggesting that TA modified gut microbial community composition and then improved metabolic outcome in weaning piglets. However, we found no difference in the genus level among three treatments, suggesting that the TA group had changed the undefined bacterium on the genus level and this undefined bacterium belonged to either Firmicutes or Bacteroidetes phylum level. Moreover, we also predicted that TA in the diet changed the functions of gut microbiota, such as phototrophy, photoautotrophy, and oxygenic-photoautotrophy. Consistent with these predicted functions, studies in cucumber also found the predicted function of phototrophy, photoautotrophy, and oxygenic-photoautotrophy (Wang et al., 2018). The function of phototrophy, photoautotrophy, and oxygenic-photoautotrophy are associated with harvesting of energy of autotrophic bacteria (Koblízek et al., 2007). This may be because TA modified the composition of autotrophic bacteria, thus has the same predicted function as cucumber. In addition, our results showed that the colonic bacterium correlated with growth performance, intestinal morphology, and intestinal nutrients carrier of the weaning pigs. These innovative results showed that TA takes charge of an intestinal bacterial regulator, which may further regulate the swine growth and intestinal absorption.

In conclusion, dietary supplementation with the dose of 500 to 1,500 mg/kg microencaspulated TA (extracted from Chinese gallnut) has no adverse effect on growth performance, palatability, organ development, intestinal growth parameters, and gastrointestinal content pH value in weaning piglets. The dose of 1,000 mg/kg microencaspulated TA improves the intestinal morphology and intestinal nutrients carrier and modulates intestinal microbiota. These findings provide new insights into suitable alternatives to antibiotics in swine production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hunan Science and Technology Project (2017XK2020), the Hunan Science and Technology Leading Talent Project (2019RS3022), the Xiaoxiang Scholar Distinguished Professor Fund of Hunan Normal University, and the National Thousand Young Talents Program and the Hunan Hundred Talents Program.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADFI

average daily feed intake

- ADG

average daily growth

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- BW

body weight

- CDD

crypt depth of duodenum

- CDI

crypt depth of ileum

- CDJ

crypt depth of jejunum

- FCR

feed conversion ratio

- LEfSe

linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size measurements analysis

- LI

large intestine

- OTU

operational taxonomic unit

- PCoA

principal co-ordinates analysis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SI

small intestine

- SLC15A1

solute carrier family 15, member 1

- SLC1A1

solute carrier family 1, member 1

- SLC5A1

solute carrier family 5, member 1

- SLC6A19

solute carrier family 6, member 19

- SLC7A9

solute carrier family 7, member 9

- TA

tannic acid

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Azagheswari B. K., Padma S., and Priya S. P.. . 2015. A review on microcapsules. Global J. Pharmacol. 9:28–39. doi: 10.5829/idosi.gjp.2015.9.1.91110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansode S. S., Banarjee S. K., and Gaikwad D. D.. . 2010. Microencapsulation: a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 1:38–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00569928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barszcz M., Taciak M., and Skomiał J.. . 2011. A dose-response effects of tannic acid and protein on growth performance, caecal fermentation, colon morphology, and β-glucuronidase activity of rats. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 20:613–625. doi: 10.22358/jafs/66219/2011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barszcz M., Taciak M., Tuśnio A., and Skomiał J.. . 2018. Effects of dietary level of tannic acid and protein on internal organ weights and biochemical blood parameters of rats. PLoS One. 13:e0190769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagia G., Cipollini I., Paulicks B. R., and Roth F. X.. . 2010. Effect of tannins on growth performance and intestinal ecosystem in weaned piglets. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 64:121–135. doi: 10.1080/17450390903461584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilić-Šobot D., Kubale V., Škrlep M., Čandek-Potokar M., Prevolnik Povše M., Fazarinc G., and Škorjanc D.. . 2016. Effect of hydrolysable tannins on intestinal morphology, proliferation and apoptosis in entire male pigs. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 70:378–388. doi: 10.1080/1745039X.2016.1206735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus M., Dolinšek J., Cencič A., and Škorjanc D.. . 2013. Effect of chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) wood tannins and organic acids on growth performance and faecal microbiota of pigs from 23 to 127 days of age. Bulgarian. J. Agric. Sci. 19:841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Butler L G. 1992. Antinutritional effects of condensed and hydrolyzable tannins[M]//Plant polyphenols. Boston (MA):Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Tan B., Xia Y., Liao S., Wang M., Yin J., Wang J., Xiao H., Qi M., Bin P., . et al. 2019. Effects of dietary gamma-aminobutyric acid supplementation on the intestinal functions in weaning piglets. Food Funct. 10:366–378. doi: 10.1039/c8fo02161a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. T., Wong T. Y., Wei C. I., Huang Y. W., and Lin Y.. . 1998. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 38:421–464. doi: 10.1080/10408699891274273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly M. L., Lovegrove J. A., and Tuohy K. M.. . 2010. In vitro evaluation of the microbiota modulation abilities of different sized whole oat grain flakes. Anaerobe 16:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim R., Liang J. B., Jahromi M. F., Shokryazdan P., Ebrahimi M., Chen W. L., and Goh Y. M.. . 2015. Effects of tannic acid on performance and fatty acid composition of breast muscle in broiler chickens under heat stress. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 14:3956. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2015.3956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P. B., Bik E. M., Bernstein C. N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., Gill S. R., Nelson K. E., and Relman D. A.. . 2005. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H. J., Scott K. P., Louis P., and Duncan S. H.. . 2012. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9:577. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard M., Thanner S., Pradervand N., Hu D., Ollagnier C., and Bee G.. . 2018. Hydrolysable chestnut tannins for reduction of postweaning diarrhea: efficacy on an experimental ETEC F4 model. PLoS One. 13:e0197878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresse R., Chaucheyras-Durand F., Fleury M. A., Van de Wiele T., Forano E., and Blanquet-Diot S.. . 2017. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in postweaning piglets: understanding the keys to health. Trends Microbiol. 25:851–873. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Zhang X. L., Wang D. W., Li L. Y., Liu G. L., Li A. K., and Zhao Y. X.. . 2013. Effects of microencapsulated Enterococcus fecalis CG1.0007 on growth performance, antioxidation activity, and intestinal microbiota in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. 91:4374–4382. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervert-Hernández D., and Goñi I.. . 2011. Dietary polyphenols and human gut microbiota: a review. Food. Rev. Int. 27:154–169. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2010.535233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. O., Wyatt H. R., and Peters J. C.. . 2012. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 126:126–132. doi: 10.1161/Circulationaha.111.087213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenshell L. M., Cunnick J. E., Ford S. P., Kattesh H. G., Zimmerman D. R., Wilson M. E., Matteri R. L., Carroll J. A., and Lay D. C. Jr. 2000. Few differences found between early- and late-weaned pigs raised in the same environment. J. Anim. Sci. 78:38–49. doi: 10.2527/2000.78138x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C. J., Li F. N., Duan Y. H., Yin Y. L., and Kong X. F.. . 2019. Dietary supplementation with leucine or in combination with arginine decreases body fat weight and alters gut microbiota composition in finishing pigs. Front. Microbiol. 10:1767. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Liu X., Zhao G., Hu T., and Wang Y.. . 2018. Potential and challenges of tannins as an alternative to in-feed antibiotics for farm animal production. Anim. Nutr. 4:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indiani C. M. D. S. P., Rizzardi K. F., Castelo P. M., Ferraz L. F. C., Darrieux M., and Parisotto T. M.. . 2018. Childhood obesity and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the gut microbiota: a systematic review. Child. Obes. 14:501–509. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandhyala S. M., Talukdar R., Subramanyam C., Vuyyuru H., Sasikala M., and Nageshwar Reddy D.. . 2015. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 21:8787–8803. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata K., Yoshioka Y., and Terao J.. . 2019. Role of intestinal microbiota in the bioavailability and physiological functions of dietary polyphenols. Molecules. 24:370. doi: 10.3390/molecules24020370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblízek M., Masín M., Ras J., Poulton A. J., and Prásil O.. . 2007. Rapid growth rates of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in the ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2401–2406. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallès J. P., Bosi P., Smidt H., and Stokes C. R.. . 2007. Nutritional management of gut health in pigs around weaning. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 66:260–268. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Shinde P., Choi J. Y., Kwon I. K., Lee J. K., and Chae B. J.. . 2009. Effects of tannic acid added to diets containing low level of iron on performance, blood hematology, iron status and fecal microflora in weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 51: 503–510. doi: 10.5187/JAST.2009.51.6.503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Shinde P. L., Choi J. Y., Kwon I. K., Lee J. K., Pak S. I., and Chae B. J.. . 2010. Effects of tannic acid supplementation on growth performance, blood hematology, iron status and faecal microflora in weanling pigs. Livest. Sci. 131:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2010.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mannelli F., Minieri S., Tosi G., Secci G., Daghio M., Massi P., and Antongiovanni M.. . 2019. Effect of chestnut tannins and short chain fatty acids as anti-microbials and as feeding supplements in broilers rearing and meat quality. Animals. 9:659. doi: 10.3390/ani9090659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach C. M. 2nd, and Gorelick F.. . 2007. Development and physiological regulation of intestinal lipid absorption. II. Dietary lipid absorption, complex lipid synthesis, and the intracellular packaging and secretion of chylomicrons. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 293:G645–G650. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00299.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min L. Y., and Longton R. E.. . 1993. Mosses and the production of Chinese gallnuts. J. Bryol. 17:421–430. doi: 10.1179/jbr.1993.17.3.421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modina S. C., Polito U., Rossi R., Corino C., and Di Giancamillo A.. . 2019. Nutritional regulation of gut barrier integrity in weaning piglets. Animals. 9:1045. doi: 10.3390/ani9121045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller‐Harvey I. 2006. Unravelling the conundrum of tannins in animal nutrition and health. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 86:2010–2037. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2577 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2012. Nutrient requirements of swine. 11th rev. ed. Washington (DC):The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pluske J. R., Hampson D. J., and Williams I. H.. . 1997. Factors influencing the structure and function of the small intestinein the weaned pig: a review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 51:215–236. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(97)00057-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rastmanesh R. 2011. High polyphenol, low probiotic diet for weight loss because of intestinal microbiota interaction. Chem. Biol. Interact. 189:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopchand D. E., Carmody R. N., Kuhn P., Moskal K., Rojas-Silva P., Turnbaugh P. J., and Raskin I.. . 2015. Dietary polyphenols promote growth of the gut bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and attenuate high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 64:2847–2858. doi: 10.2337/db14-1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J. L., and Mazmanian S. K.. . 2009. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. H., and Mackie R. I.. . 2004. Effect of condensed tannins on bacterial diversity and metabolic activity in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1104–1115. doi: 10.1128/aem.70.2.1104-1115.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer F., Anderson J. M., Bharti R., Raes J., and Rosenstiel P.. . 2017. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15:630–638. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starčević K., Krstulović L., Brozić D., Maurić M., Stojević Z., Mikulec Ž., Miroslav B., and Mašek T.. . 2015. Production performance, meat composition and oxidative susceptibility in broiler chicken fed with different phenolic compounds. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 95:1172–1178. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B. R. 2010. Amino acid transport by epithelial membranes [M]. In: Gerencser G. editor, Epithelial transport physiology. New York (MA): Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang M., Laarveld B., Van Kessel A. G., Hamilton D. L., Estrada A., and Patience J. F.. . 1999. Effect of segregated early weaning on postweaning small intestinal development in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 77:3191–3200. doi: 10.2527/1999.77123191x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonda R. M., Rubach J. K., Lumpkins B. S., Mathis G. F., and Poss M. J.. . 2018. Effects of tannic acid extract on performance and intestinal health of broiler chickens following coccidiosis vaccination and/or a mixed-species Eimeria challenge. Poult. Sci. 97:3031–3042. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretola M., Maghin F., Silacci P., Ampuero S., and Bee G.. . 2019. Effect of supplementing hydrolysable tannins to a grower–finisher diet containing divergent pufa levels on growth performance, boar taint levels in back fat and intestinal microbiota of entire males. Animals. 9: 1063. doi: 10.3390/ani9121063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallaeys L., Van Biervliet S., De Bruyn G., Loeys B., Moring A. S., Van Deynse E., and Cornette L.. . 2013. Congenital glucose-galactose malabsorption: a novel deletion within the SLC5A1 gene. Eur. J. Pediatr. 172:409–411. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1802-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. M., Huang H. J., Liu S., Zhuang Y., Yang H. S., Li L. Y., Chen S., Wang L. X., Yin L. M., Yao Y. F., . et al. 2019. Tannic acid modulates intestinal barrier functions associated with intestinal morphology, antioxidative activity, and intestinal tight junction in a diquat-induced mouse model. RSC. Adv. 9: 31988–31998. doi: 10.1039/C9RA04943F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li Q., Xu S., Zhao W., Lei Y., Song C., and Huang Z.. . 2018. Traits-based integration of multi-species inoculants facilitates shifts of indigenous soil bacterial community. Front. Microbiol. 9:1692. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windisch W., Schedle K., Plitzner C., and Kroismayr A.. . 2008. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. J. Anim. Sci. 86(14 Suppl):E140–E148. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. S., Wu F., Long L. N., Li T. J., Xiong X., Liao P., Liu H. N., and Yin Y. L.. . 2016. Effects of yeast products on the intestinal morphology, barrier function, cytokine expression, and antioxidant system of weaned piglets. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 17:752–762. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Xiong X., and Yin Y.. . 2013. Development and renewal of intestinal villi in pigs. In: Blachier F., Wu G., and Yin Y., editors. Nutritional and physiological functions of amino acids in pigs. Vienna: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1328-83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M. D., Di L. F., Tang Z. Y., Jiang W., and Li C. Y.. . 2019. Effect of tannins and cellulase on growth performance, nutrients digestibility, blood profiles, intestinal morphology and carcass characteristics in Hu sheep. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 32:1540–1547. doi: 10.5713/ajas.18.0901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong E. Y., Huang P. F., Zhang W., Li J. Z., Li Y. L., Ding X. Q., Xiong X., Yin Y. L., and Yang H. S.. . 2018. The effects of dietary sulfur amino acids on growth performance, intestinal morphology, enzyme activity, and nutrient transporters in weaning piglets. J. Anim. sci. 96:1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/jas/skx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.